ABSTRACT

Role modelling has been identified as an important phenomenon in medical education. Key reports have highlighted the ability of role modelling to support medical students towards careers in family medicine although the literature of specific relevance to role modelling in speciality has not been systematically explored. This systematic review aimed to fill this evidence gap by assimilating the worldwide literature on the impact of role modelling on the future general practitioner (GP) workforce. A systematic search was conducted in Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane, ERIC and CINAHL, and all authors were involved in the article screening process. A review protocol determined those articles selected for inclusion, which were then quality assessed, coded and thematically analysed. Forty-six articles were included which generated four broad themes: the identity of role models in general practice, role modelling and becoming a doctor, the impact of role modelling on attitudes towards the speciality, and the subsequent influence on behaviours/career choice. Our systematic review confirmed that role modelling in both primary and secondary care has a crucial impact on the future GP workforce, with the potential to shape perceptions, to attract and deter individuals from the career, and to support their development as professionals. Role modelling must be consciously employed and supported as an educational strategy to facilitate the training of future GPs.

Introduction

As the world recovers from the Covid-19 pandemic, primary care systems globally will shoulder an increasing healthcare burden. Doctors with a generalist skillset and aspirations to work in general practice or family medicine will be in significant demand, and it is crucial to consider the factors that may influence and deter from these ambitions.

Many variables influence individuals’ decisions to choose a career in family medicine, including workload, lifestyle preferences and organisational influences [Citation1], in addition to valuing long-term doctor–patient relationships and the ability to see a broad spectrum of patients [Citation2]. The influence of role models on the choice of medical career has long been recognised [Citation3,Citation4]. The United Kingdom (UK) reports: ‘Destination GP’ [Citation5] and ‘By choice not by chance’ [Citation6] highlighted the importance of role models in supporting individuals towards careers in family medicine. However, literature of specific relevance to role modelling in the speciality has not been systematically explored.

A 2013 systematic review of role modelling in medical education [Citation4] confirmed the impact of this educational phenomenon on career choice, discussing attributes of positive role models, positive and negative role modelling, and the influence of culture, diversity and gender on the choice of role model. Whilst these findings have relevance across all medical specialities, little is known about role modelling specifically in the context of primary care medical education. The aim of this systematic review was to explore the worldwide literature focussing on the impact of role modelling in preparing the future family medicine workforce.

For the purposes of this review, the following definition of a role model has been selected: ‘a significant person on which an individual patterns his or her behaviour in a particular social role, including adopting appropriate similar attitudes’ [Citation7]. Role models function as ‘active cognitive constructions devised by individuals to construct their ideal or possible selves, based on their own developing needs and goals’ [Citation8]. Therefore, a medical role model is any doctor with the potential to influence the attitudes, career choice and professional development of the individuals exposed to their example.

The role modelling process is complex: individuals learn from role models through an active process of engagement, appraisal and selection of those suggestions, which are relevant to them, and construction of knowledge from the experience [Citation9]. Social learning theory describes how people learn from each other through observation, imitation and modelling [Citation10], doctors learn their profession through imitation of clinicians they respect and trust. They do this through conscious and unconscious observation and reflection, incorporating observed actions into their own values and behaviours [Citation11]. Role modelling in medical education takes place in the formal, informal and hidden curricula, where learning is ‘captured, fixed and made manifest in how doctors actually set about the tasks of medicine’ [Citation12]. Studies have discussed the attributes of positive medical role models, which can be broadly grouped into clinical competence, teaching skills and personal qualities, such as compassion, honesty and integrity [Citation3,Citation13–16]. Given the potential of this educational phenomenon to influence the future medical workforce, in a climate of increasing demand for generalist clinicians, it is crucial that positive role modelling in family medicine is facilitated and areas for intervention identified.

Review objectives

This review aimed to contribute to the literature described above by answering the following questions:

What is the impact of role modelling in medical education in preparing the future family medicine workforce?

How do role models influence attitudes towards careers in family medicine or general practice?

What attributes are described in general practitioner role models and what impact do they have on professional skills development?

Review methodology

Systematic review was selected as an appropriate method to assimilate the literature, aiming to systematically search for, appraise and synthesise research evidence [Citation17], to draw together all available knowledge on the research topic. The review methodology was based on recommendations by the Best Evidence Medical Collaboration [Citation18]. The review protocol (Appendix 1) demonstrates the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were developed using the Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome (PICO) framework outlined in .

Table 1. PICO framework used to develop review criteria.

displays the search terms, databases used, inclusion criteria and process. This strategy was developed with the assistance of the Faculty of Medical Sciences librarian.

Box 1. Review search terms, databases, inclusion criteria and process

Included studies were coded on individual data abstraction sheets, supporting identification of the main findings of relevance to the concepts, which informed the review questions. The extracted data were then thematically analysed, following the framework described by Braun and Clarke [Citation19]. The methodological quality of each included study was then assessed using a series of quality indicators validated in the Best Evidence in Medical Education guide 11 [Citation18] and used in a systematic review discussing doctor role modelling in medical education [Citation4], see Appendix 2.

Results

demonstrates the article selection process, which adhered to the PRISMA checklist [Citation20]. In total, 1,544 articles were screened, leading to a selection of 46 primary research papers. Each article was summarised on an Excel spreadshee. Higher quality studies were considered to have met at least nine out of 11 of the quality indicators, medium quality seven or eight, and lower quality papers those that scored six or below.

Figure 1. Prisma 2009 flow diagram [Citation20] detailing the article selection process.

![Figure 1. Prisma 2009 flow diagram [Citation20] detailing the article selection process.](/cms/asset/605d3a36-7fad-4717-aec7-00bf56480e09/tepc_a_2079097_f0001_oc.jpg)

Most of the included articles were from the UK and North America, with others from Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Ghana, Finland, Switzerland, and Saudi Arabia. Most papers were published between 2000 and 2020, with five published in the 1990s. Thirty-one primary research papers were rated as high quality, 14 were medium and one low quality. The most common research method was survey, followed by interviews and focus groups. Thematic analysis of included articles and discussion between all authors led to the development of four broad themes, which were as follows: the identity of role models in general practice, role modelling and becoming a doctor, the impact of role modelling on attitudes towards the speciality and the subsequent impact on behaviours/career choice. summarises the included articles and themes.

Table 2. A summary of the included articles and their allocated themes.

Theme one: the identity of role models in family medicine

In this first theme, we discuss what makes a family medicine doctor, or general practitioner (GP) a role model, in what context they act and their attributes. Role models are crucial in shaping future doctors, who are particularly likely to be influenced by role models who match their personalities, values and represent ‘possible selves’ [Citation21]. Positive role models appear to be of particular importance in influencing those who choose to specialise in family medicine, less so for those who elect to specialise in secondary care. Role models play a vital role in helping students to understand the role of a GP, making explicit the values of the speciality and supporting students who share those values towards a career in general practice [Citation22].

GP educators are commonly identified as role models [Citation23], longitudinal community placements are an ideal context for exposure to the role modelling process [Citation24], and GP trainees are described as effective role models acting as powerful advocates for the role [Citation25]. GPs in the media, direct personal experience of a GP as a patient, and having a GP parent were identified as role modelling encounters [Citation26].

The explored literature provides limited insight into differences in individual characteristics such as gender and ethnicity in the identification of a role model. There is conflicting information on the link between gender and the identification of GP role models, with some studies suggesting men are more likely than women to cite role models in influencing their decision to choose general practice [Citation27,Citation28], and others suggesting women are more likely to identify a GP role model [Citation22]. Individuals from some minority and white ethnic groups may be less likely to identify a role model [Citation22].

Positive role model attributes described in the literature include demonstrating enthusiasm towards patients, students and teaching; dedication to the career; creating a safe and comfortable environment; being open to reveal the ‘human’ behind the clinician and honesty about the challenges faced [Citation24]. Key to providing a positive role model are good communication skills, non-judgemental attitudes [Citation29], showing empathy [Citation21], demonstrating holistic care and being knowledgeable and genuinely interested in patients [Citation30–32]. Positive role models are visionary leaders [Citation33] who are compassionate, inspiring [Citation34] organised [Citation26], demonstrate intellectual curiosity and a good work–life balance [Citation23].

Negative behaviours were witnessed in GP role models, including taking shortcuts in examination skills, treating ‘patients like a production line’, demonstrating prejudice, failing to interact with students [Citation26], poor interpersonal relationships [Citation34] and poor communication skills [Citation31]. Furthermore, GPs were witnessed ‘bashing’ their own speciality [Citation35].

Medium and low scoring papers reinforced the findings described above around communication skills [Citation36]. In addition, teaching effectiveness was found to be independently associated with providing a good role model [Citation37], and conscious role modelling was deemed a professional responsibility of educators [Citation38,Citation39]. GP role models can have an important impact before medical school during student work experience, raising awareness of the speciality to school pupils [Citation40]. Additional positive attributes to those detailed above include providing continuity of care [Citation41] and demonstrating clinical reasoning skills [Citation42].

Theme two: role modelling and becoming a doctor

The review identified several high-quality papers discussing the impact of role modelling on professional development of future doctors and developing the skillset of a GP. Doctor role modelling in medical education is critically important in the professional development, character development and professional identity formation of future doctors, effectively ‘enhancing the transformation of the student to a doctor’ [Citation43]. Participants in this study developed an idea of what ‘type’ of doctor they would like to become, not just what speciality they will choose, through role modelling and emphasised the value of ‘emulating the role model’s unique approach and styles’. A subsequent grounded theory study led by the same authors [Citation44] generated an explanation of the process of modelling and how it leads to behaviour change through exposure to the role model, critical appraisal of the behaviours observed and then a model-trialling cycle of behaviours.

Students undergo a socialisation process at medical school where they transition from a lay person to a doctor. Crucial in this process is the role model, whose values they internalise and adopt, shaping their professional identity [Citation35]. Role models are of utmost importance in the development of humanism [Citation45], and through role modelling, future doctors develop professional skills including doctor–patient relationship, continuity of care and prescribing habits [Citation41,Citation46,Citation47]. Role models demonstrate the opportunity for portfolio careers and special interests, such as obstetric care [Citation48]. Role modelling is important in developing leadership skills [Citation33]. Interestingly, witnessing poor leadership and navigating the strains of professional life can provide as rich an opportunity for learning as exposure to good leadership role models. Indeed, this learning opportunity from negative experiences is key in creating ‘good doctors’ [Citation31].

Theme three: the impact of role models on attitudes towards family medicine

Role models play a critical role in forming perceptions of family medicine. Personal experience of GPs has been identified as the most important factor influencing attitudes of undergraduates to the speciality [Citation49], while secondary care clinicians can play a significant role in development of negative perceptions of the speciality [Citation35]. GP role models often promote the speciality, combat negative stereotyping and increase understanding of what it means to be a ‘good GP’ [Citation22,Citation50]. Witnessing the job satisfaction of role models in providing continuity of care and caring for patients with complex co-morbidity shapes a positive view of the profession [Citation51,Citation52].

A large international study [Citation53] highlighted the importance of GP role models in contributing to undergraduate perceptions, describing that through witnessing positive GP role models, UK students perceived a career in family medicine to provide autonomy, diversity of practice, a good quality of life and work–life balance. However, in Canada, France and Spain, family medicine was not as well regarded, and disgruntled role models had a negative impact on perceptions. This positive UK experience is contradicted to some degree by a survey-based study, which explored perceptions of UK medical students around careers in general practice. Many respondents cited particular GPs shaping perceptions that GPs have lower status than hospital specialists, that the role lacks intellectual challenge, limited research opportunities, and that GPs were stressed, lacked autonomy and unfulfilled [Citation25]. Further studies [Citation35,Citation54] confirm that role models contributed to the perception that family medicine lacked prestige and challenge, and some role models were perceived to be dissatisfied with their career.

Attitudes were affected through role models outside of training in general practice. Participants with GP parents in a UK-based study described the negative impact of witnessing them working long hours, and GP role models in the media were seen as ‘not actually doing anything’ and not mentioned in ‘exciting’ dramas [Citation26]. Role models in the media seem to be particularly influential to early-stage medical students, perhaps because they have less opportunity for engagement with real GP role models, who are responsible for improving perceptions of the speciality as they progress through training [Citation49]. Role models in factual media contributed to negative perceptions, and Harold Shipman was mentioned by many students as influencing their attitude towards the speciality [Citation26].

Concerningly, hospital role models are influential in shaping negative perceptions of family medicine [Citation26] and GP trainees witnessed secondary care role models commenting on the speciality being boring, ‘a waste of training’ and a ‘second-class career choice’, reinforcing a negative perception of being ‘just a GP’ [Citation55]. Students perceived the job of a GP as ‘difficult to do well’ as they witnessed secondary care role models ‘bashing GPs’ and their ‘poor’ or ‘inappropriate referrals’ [Citation35]. Medium and low scoring papers provide further evidence of role modelling influencing the perceptions of future doctors [Citation40,Citation56] and role models contributing to a perceived lack of intellectual challenge in the speciality [Citation57].

Theme four: the influence of role modelling on career choice

Role modelling is crucial in shaping the attitudes of the future workforce towards general practice. This section summarises findings from the included literature discussing the influence of role modelling on choosing a career in general practice.

Having a GP role model is a significant predictor of entering a career in the speciality, an effect that at the time of this study appeared to be stronger in junior doctors than students [Citation58]. Those who have chosen the speciality and identify a GP role model are more likely to have trained at a university where family medicine was encouraged, and individuals were more likely to be satisfied with their career choice [Citation22]. Exposure to GP role models through high quality, early placements positively influences students’ views on a career in the speciality [Citation50,Citation51,Citation59,Citation60] and relationships with GP role models have a lasting effect on a decision to choose a career in general practice [Citation46,Citation55,Citation61]. GP role models are crucial in a matching process between understanding the role of a GP and increasing understanding of the self, resulting in a desire to enter family medicine [Citation24].

Witnessing the administrative burden in GP role models, negative behaviours [Citation26,Citation54], appearing dissatisfied with their job [Citation52] and secondary care role models [Citation55] all have the potential to deter future doctors from a GP career. Medium and low scoring papers confirmed that role models attract [Citation62,Citation63] and deter trainees from pursuing a career in the speciality [Citation64,Citation65]. Role models appear to be of greater importance in influencing career choice towards primary care than secondary care specialities, particularly for male students [Citation66].

Discussion

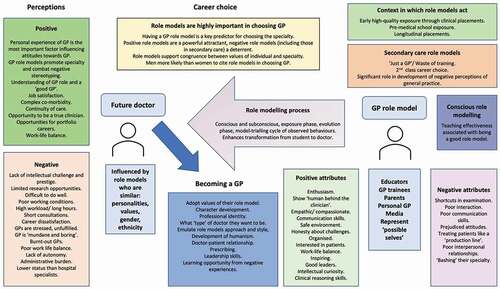

Our systematic review has confirmed the importance of role modelling in influencing the future family medicine workforce, highlighting that the role modelling process not only affects attitudes to and career decisions towards the speciality but also affects the process of becoming a doctor. We have included the findings from 46 relevant primary research articles from around the world and of particular importance, we have identified the powerful impact of denigration of general practice from role models in both primary and secondary care, and the perceived lack of intellectual challenge and research opportunities in the speciality. We have confirmed the importance of students being exposed to GP role models, ideally through high quality, longitudinal placements. We have described the importance of the GP role model in developing professional identity in future doctors, shaping their understanding of the values of the speciality, development of humanism, leadership and communication skills. summarises the review findings.

Figure 2. A summary of the attributes of GP role models and the influence of the role modelling process on perceptions, behaviours and career choice.

Our findings on the influence of GP role models on the professional development of future doctors are supported by a systematic review of undergraduate medical education in general practice [Citation67], which identified a vital component of training as observing role models in action, allowing students to observe, think and develop professional attitudes and behaviours, which mirror their role models. According to social learning theory [Citation10] individuals pay attention to role models because they believe they can learn professional skills and attributes from them, particularly if they observe behaviour aligned with their views of what is important about being a doctor. Therefore, it is crucial that GPs involved in teaching role model consciously, and demonstrate appropriate attitudes and behaviours, as they have the potential to have a profound influence on the attributes of the future medical workforce.

Our review identified that some medical students and trainees were deterred from a career in general practice as they perceived GPs to be stressed with high workloads and a job that was difficult to do well. An international review highlighted that GPs were particularly prone to burnout and that burnout appeared to be frequent amongst those training in the speciality [Citation68]. We found that GP trainees can be particularly effective and positive role models. Reports suggested medical schools worldwide now have formal arrangements for GP trainees to teach medical undergraduates [Citation69–72]. Trainees are often more cognitively and socially congruent with their learners [Citation73] and using near-peer role models to teach medical students is encouraged in the recommendations made in ‘By Choice not by Chance’ [Citation6]. However, trainees face stress and workload pressures, and may be more susceptible to burnout. A study that analysed the personality traits of GP trainers compared with GP trainees found that trainees reported lower levels of emotional resilience [Citation74], and a Hungarian study identified moderate-to-high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation in both groups but higher in trainees [Citation75]. While those considering a career in the speciality need to see the realities of the role, it is important to consider how to support the GP workforce to remain positive advocates for their career while also role modelling a positive approach to the realities of the job and the stressors entailed.

We identified that role models in general practice may be perceived to have lower status than hospital specialists, with limited academic opportunities, and students witnessed GP role models ‘bashing’ their own speciality. The influence of secondary care clinicians in promoting the idea that general practice is a second-rate career is concerning. The motivational theory of role modelling [Citation76] described that role models represent the possible and provide inspiration. Lack of academic possibilities and negativity towards the speciality is likely to de-motivate students from aspiring to a career in general practice. Future doctors are high achieving, highly intelligent individuals, and if they perceive general practice to be boring and not academic, it is questionable whether they will identify with that role.

Evidence has suggested that individuals were more likely to identify role models who they perceive as sharing similarities to them. The social comparison theory [Citation8] supports this finding, suggesting that individuals are drawn to people who they perceive as similar to themselves, and represent an aspect of what the individual would like to become. The interplay between intersectional identity and role models is likely to be complex. The literature describing this relationship was limited to quantitative data suggesting a correlation between gender and ethnicity and the identification of a role model. It is important that this area is further explored with qualitative work. Box 2 has suggestions for further research to explore pertinent questions around personal attributes and identity of role models amongst other key topics.

Based on our review findings, we recommend that the following steps described in are taken to ensure role modelling is used to its full potential in supporting doctors towards careers in general practice.

Table 3. Implications for practice.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review is the first we are aware of to highlight the importance of role modelling as an educational strategy in securing the future family medicine workforce. Our systematic search strategy allowed exploration of several key areas of interest enhanced by thematic analysis. This led to the development of several practical recommendations, which have the potential to impact on future GPs. However, this review had limitations. Limiting our findings to English language articles meant we may have missed other international evidence. Using role model/role modelling in our search terms meant we may have missed articles that described a role model in another way, for example, a mentor.

Conclusion

Our systematic review highlighted the importance of the future workforce being exposed to positive GP role models to favourably shape perceptions, career choices towards general practice and the development of generalist attributes. The review highlighted the potential detrimental impact of negative role modelling by doctors in both primary and secondary care, which can deter future doctors from careers in general practice. Further steps must be taken to increase awareness of the professional responsibility as a GP and secondary care doctor to act as a positive role model to future doctors, and institutional support must be provided to role models to enable them to act consciously and positively to support the future GP workforce.

Box 2. Recommendations for future research

Acknowledgments

Elizabeth Lamb is funded by the National Institute for Health Research as an In Practice Fellow. The authors thank Ms Aimee Cook, Faculty of Medical Sciences Librarian at Newcastle University, for her support with building the search strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Spooner S, Laverty L, Checkland K. The influence of training experiences on career intentions of the future GP workforce: a qualitative study of new GPs in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):e578–e85.

- Deutsch T, Lippmann S, Frese T, et al. Who wants to become a general practitioner? Student and curriculum factors associated with choosing a GP career - a multivariable analysis with particular consideration of practice-orientated GP courses. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(1):47–53.

- Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):53–56.

- Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, et al. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME guide no. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422–36.

- Royal College of General Practitioners. 2021 Destination GP: medical students’ experiences and perceptions of general practice 2017. [ cited 2021 Nov 18]; cited: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/training-exams/discover-general-practice/medical-students/shaping-general-practice.aspx.

- Wass V. By choice- not by chance. 2016. [cited 2021 Nov 21]. https://www.medschools.ac.uk/studying-medicine/after-medical-school/specialty-focus-general-practice:MedicalschoolscouncilHealthEducationEngland.

- Scott J, Marshall G. A dictionary of sociology. Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Gibson DE. Role models in career development: new directions for theory and research. J Vocat Behav. 2004;65(1):134–156

- Billett S. Mimetic learning at work: learning in the circumstances of practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG; 2014.

- Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1977.

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Teaching rounds: role modelling: making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008;336(7646):718–721.

- Marinker M. Myth, paradox and the hidden curriculum. Med Educ. 1997;31(4):293–298.

- Wright SM, Carrese JA. Excellence in role modelling: insight and perspectives from the pros. Cmaj. 2002;167(6):638–643.

- Côté L, Leclère H. How clinical teachers perceive the doctor—patient relationship and themselves as role models. Acad Med. 2000;75(11):1117–1124.

- Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1203–1210.

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libraries J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

- Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, et al. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):282–298.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

- Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, et al. A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):534–541.

- Kutob RM, Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D. The diverse functions of role models across primary care specialties. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):244–251.

- Reitz R, Sudano L, Siler A, et al. Balancing the roles of a family medicine residency faculty: a grounded theory study. Fam Med. 2016;48(5):359–365.

- Mackie E, Alberti H. Longitudinal GP placements – inspiring tomorrow’s doctors? Educ Primary Care. 2020;31(1):1–8.

- Barber S, Brettell R, Perera-Salazar R, et al. UK medical students’ attitudes towards their future careers and general practice: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative analysis of an Oxford cohort. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):160.

- Firth A, Wass V. Medical students’ perceptions of primary care: the influence of tutors, peers and the curriculum. Educ Primary Care. 2007;18(3):364–372.

- Roos M, Watson J, Wensing M, et al. Motivation for career choice and job satisfaction of GP trainees and newly qualified GPs across Europe: a seven countries cross-sectional survey. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25(4):202–210.

- Xu G, Rattner SL, Veloski JJ, et al. A National Study of the Factors Influencing Men and Women Physicians Choices of Primary care specialities. Acad Med. 1995;70(5):398–404.

- Silverstone Z, Whitehouse C, Willis S, et al. Students’ conceptual model of a good community attachment. Med Educ. 2001;35(10):946–956.

- Jochemsen-Van Der Leeuw HGAR, Van Dijk N, Wieringa-De Waard M. Assessment of the clinical trainer as a role model: a role model apperception tool (RoMAT). Acad Med. 2014;89(4):671–677.

- Miettola J, Mantyselka P, Vaskilampi T. Doctor-patient interaction in Finnish primary health care as perceived by first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1). DOI:10.1186/1472-6920-5-34

- Lublin JR. Role modelling: a case study in general practice. Med Educ. 1992;26(2):116–122.

- Nicol JW, Gordon LJ. Preparing for leadership in General Practice: a qualitative exploration of how GP trainees learn about leadership. Education for primary care: an official publication of the association of course organisers, National Association of GP tutors, World Organisation of Family Doctors. Educ Primary Care. 2018;29(6):327–335.

- Amalba A, Abantanga FA, Scherpbier AJJA, et al. Community-based education: the influence of role modeling on career choice and practice location. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):174–180.

- Reid K, Alberti H. Medical students’ perceptions of general practice as a career; a phenomenological study using socialisation theory. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(4):208–214.

- Essers G, Van Weel-Baumgarten E, Bolhuis S. Mixed messages in learning communication skills? Students comparing role model behaviour in clerkships with formal training. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):e659–65.

- Elnicki DM, Kolarik R, Bardella I. Third-year medical students’ perceptions of effective teaching behaviors in a multidisciplinary ambulatory clerkship. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):815–819.

- Mann KV, Holmes DB, Hayes VM, et al. Community family medicine teachers’ perceptions of their teaching role. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):278–285.

- Riesenberg LA, Biddle WB, Erney SL. Medical student and faculty perceptions of desirable primary care teaching site characteristics. Med Educ. 2001;35(7):660–665.

- Curtis A, Main J, Main P, et al. ‘Getting them early’: the impact of early exposure to primary care on career choices of A-level students – a qualitative study. Educ Primary Care. 2008;19(3):274–284.

- Delva D, Kerr J, Schultz K. Continuity of care: differing conceptions and values. Can Family Physician. 2011;57(8):915–921.

- Ambrozy DM, Irby DM, Bowen JL, et al. Role models’ perceptions of themselves and their influence on students’ specialty choices. Acad Med. 1997;72(12):1119–1121.

- Passi V, Johnson N, The impact of positive doctor role modeling. Med Teach. 2016;38(11):1139–1145.

- Passi V, Johnson N. The hidden process of positive doctor role modelling. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):700–707.

- Moyer CA, Arnold L, Quaintance J, et al. What factors create a humanistic doctor? A nationwide survey of fourth-year medical students. Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1800–1807.

- Jordan J, Brown JB, Russell G. Choosing family medicine. What influences medical students? Can Family Physician. 2003;49:1131–1137.

- Dallas A, van Driel M, van de Mortel T, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for the future: exploring the attitudes of trainees in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(626):e561–e7.

- Biringer A, Forte M, Tobin A, et al. What influences success in family medicine maternity care education programs? Qualitative exploration. Can Family Physician. 2018;64(5):e242–e8.

- Henderson E, Berlin A, Fuller J. Attitude of medical students towards general practice and general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(478):359–363.

- Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(651):e768–75.

- Deutsch T, Honigschmid P, Frese T, et al. Early community-based family practice elective positively influences medical students’ career considerations–a pre-post-comparison. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):24.

- Meli DN, Ng A, Singer S, et al. General practitioner teachers’ job satisfaction and their medical students’ wish to join the field - a correlational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):50.

- Rodríguez C, López-Roig S, Pawlikowska T, et al. The influence of academic discourses on medical students’ identification with the discipline of family medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):660–670.

- Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third- and fourth-year students’ focus-group discussions. Acad Med. 1997;72(7):635–640.

- Alberti H, Banner K, Collingwood H, et al. ‘Just a GP’: a mixed method study of undermining of general practice as a career choice in the UK. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018520.

- Matthews C. Role modelling: how does it influence teaching in family medicine? Med Educ. 2000;34(6):443–448.

- Schafer S, Shore W, French L, et al. Rejecting family practice: why medical students switch to other specialties. Fam Med. 2000;32(5):320–325.

- Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(3):159–169.

- Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J, Kutob R. A comparison of primary care graduates from schools with increasing production of family physicians to those from schools with decreasing production. Fam Med. 2004;36(4):260–264.

- Bien A, Ravens-Taeuber G, Stefanescu MC, et al. What influence do courses at medical school and personal experience have on interest in practicing family medicine? - Results of a student survey in Hessia. GMS J Med Educ. 2019;36(1):Doc9.

- Vohra A, Ladyshewsky R, Trumble S. Factors that affect general practice as a choice of medical speciality: implications for policy development. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43(2):230–237.

- Saigal P, Takemura Y, Nishiue T, et al. Factors considered by medical students when formulating their specialty preferences in Japan: findings from a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7(1):31.

- Wiener-Ogilvie S, Begg D, Dixon G. Foundation doctors career choice and factors influencing career choice. Educ Primary Care. 2015;26(6):395–403.

- DeWitt DE, Curtis JR, Burke W. What influences career choices among graduates of a primary care training program? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):257–261.

- Ie K, Tahara M, Murata A, et al. Factors associated to the career choice of family medicine among Japanese physicians: the dawn of a new era. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1). DOI:10.1186/s12930-014-0011-2

- Knox KE, Getzin A, Bergum A, et al. Short report: factors that affect specialty choice and career plans of Wisconsin’s medical students. Wmj. 2008;107(8):369–373.

- Park S, Khan NF, Hampshire M, et al. A BEME systematic review of UK undergraduate medical education in the general practice setting: BEME guide no. 32. Med Teach. 2015;37(7):611–630.

- Bugaj TJ, Valentini J, Miksch A, et al. Work strain and burnout risk in postgraduate trainees in general practice: an overview. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(1):7–16.

- Thomson JS, Anderson K, Haesler E, et al. The learner’s perspective in GP teaching practices with multi-level learners: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):55.

- de Villiers MR, Cilliers FJ, Coetzee F, et al. Equipping family physician trainees as teachers: a qualitative evaluation of a twelve-week module on teaching and learning. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):228.

- Dick ML, King DB, Mitchell GK, et al. Vertical Integration in Teaching And Learning (VITAL): an approach to medical education in general practice. Med J Aust. 2007;187(2):133–135.

- Alberti H, Cottrell E, Cullen J, et al. Promoting general practice in medical schools. Where are we now? Educ Primary Care. 2020;31(3):162–168.

- Thampy H, Alberti H, Kirtchuk L, et al. Near peer teaching in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):12–13.

- Joffe M, MacLeod S, Kedziora M, et al. GP trainers and trainees - Trait and gender differences in personality: implications for GP training. Educ Primary Care. 2016;27(3):205–213.

- Adam S, Mohos A, Kalabay L, et al. Potential correlates of burnout among general practitioners and residents in Hungary: the significant role of gender, age, dependant care and experience. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1). DOI:10.1186/s12875-018-0886-3

- Morgenroth T, Ryan MK, Peters K. The motivational theory of role modeling: how role models influence role aspirants’ goals. Rev General Psychol. 2015;19(4):465–483.

Appendix 1:

Review protocol

Was the study published after 1990?

Is the full text available in English language?

Is the study a primary research article containing qualitative or quantitative data on GP role models or role modelling in general practice (or family medicine) and their influence or impact on either medical students or junior doctors?

Exclude editorials, letters, papers which do not present primary research.

Exclude studies discussing role modelling solely by other health professionals

Key words to include:

General practitioner/general practice/family medicine

Role models/role modelling

Medical students or junior doctor or GP trainee or resident or intern or foundation doctor or registrar

Articles should describe the impact or influence of role models or the role modelling process on the above groups; these may be perceptions, career choice, professional identify or other ways in which the decisions made by these groups are influenced.

Appendix 2:

Quality assessment tool

Reviewer:

Authors:

Year:

Country and Institution:

Total score =