ABSTRACT

Concept analysis is a useful qualitative research method for psychologists aiming to define, clarify or critique concept meaning and use in theory, practice or research. This article explains Reformative Concept Analysis (RCA), a novel method derived from nursing and political science concept analysis approaches, and reformed for applied psychology research. First, the role of concepts as epistemological vessels in psychological theory and practice is described. Some problems with concept use in clinical practice and research are highlighted, to demonstrate why critical analytic methods to improve concept definition and utility are needed. Then, overviews of some existing concept analysis methods are provided, with summaries of their strengths and limitations from an applied psychology perspective. The importance of comparing and combining meaning frameworks constructed from qualitative narratives and literature review is highlighted. Finally, the eight stages of RCA method are set out, along with some ontological, epistemological, design, rigour and presentation considerations.

Introduction

Concept analysis methods are designed to advance understanding of the meaning and function of integral concepts in research, theory and practice in social and health sciences. The purpose of this article is twofold. The first aim is to invite psychologists to consider conducting concept analysis research to solve common problems with concept use in psychological theory and therapeutic practice. The second aim is to introduce and outline Reformative Concept Analysis (RCA), a methodology synthesised and enhanced for applied psychology from nursing and political science concept analysis traditions.

In this article, applied psychology refers to the work of registered practitioner psychologists (e.g. clinical, counselling, educational, forensic, sport and exercise, occupational, and health) who use psychological theories to understand cognitive, behavioural, and emotional functions in individual, family, group, community and wider social mental health. These psychologists generally apply theoretically informed, evidence-based therapeutic approaches in direct clinical practice to promote service user or community mental health. They may also carry out research to extend understanding of key phenomena and processes in their work.

Concepts as epistemological vessels

Concepts are socially constructed abstract linguistic terms that cluster related categories of knowledge or experience into generalised, collective meaning. As thought objects, concepts are epistemological vessels that hold, shape, signify and transport ‘what is known’ about ‘how things work’ by those with power to define and replicate their view of reality and social position.

In the social sciences, concepts have been described as the building blocks of theory, with implicit explanatory powers (e.g. Chinn and Kramer Citation1994; Pintrich, Marx, and Boyle Citation1993). Conversely, Paley (Citation1996) proposed that theory creates concepts to occupy meaning niches (although by Paley (Citation2021) came to argue that concepts don’t exist). In applied psychology, theory and concept development can be interdependent activities amenable to description with 'parent and child' metaphors. Concepts might be viewed as the ‘offspring’ of theories, invented to encapsulate aspects of observed or imputed cause and effect. Once ‘born’ concepts exert formative influence on their theoretical ‘parents’ by taking on their own life in practice, theory and research (Vermes Citation2018). Psychological theories and associated concepts are developed and tested to advance and improve provision of mental health care by discerning patterns, solving problems, creating new knowledge or suggesting better ways of working. Patient-centred concepts include (but are not limited to) experiences (e.g. bereavement); traits (e.g. conscientiousness); states of being (e.g. mindfulness); attitudes (e.g. ambivalence); aspirations (e.g., empowerment) or harmful contexts (e.g. poverty). Practitioner-centred concepts include (but are not limited to) states of being (e.g. responsiveness); therapeutic techniques (e.g. Socratic questioning); clinical judgements (e.g. ‘dysfunctional’); or aspirations (e.g. alliance). But if one asks what each of these concepts means, one finds imprecise and sometimes incongruous definitions.

While inexact concept meanings are tolerated in clinical language, they are more problematic in theory and research, where they tend to form part of explanatory multi-directional causal theories. Bandura’s ‘reciprocal determinism’ model (Citation1978), for example, describes how people’s personal and cultural characteristics and social roles may shape interactions between external environmental events, and internal cognitive processes such as reflective thought, selective attention, planning and foresight, beliefs and preferences, incentives, self-evaluation and self-efficacy. If a psychologist is asked ‘within Bandura’s reciprocal determinism model what does this abstract term 'self-efficacy' mean? they may initially respond, ‘confidence to get things done’. With further thought they may say it is a composite of interrelated, less abstract concepts such as 'capability' and 'mastery'. These concepts, in turn, sit within causal process theories about the sources of self-efficacy, and their effects on a person's choice of goals and persistence expended to meet them (Bandura Citation1997). To be researchable, each concept comprising the theory needs a definitional domain that clearly distinguishes it from theoretically contiguous concepts, and ideally, renders it measurable.

A researchable concept is best defined in a brief statement of necessary and sufficient conditions such as its attributes, properties, dimensions, boundaries and entities to which it applies (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff Citation2016). Some researchers (e.g. Morse and Penrod Citation1999) suggest attributes must be present in every example of the concept. On the other hand, Wittgenstein (1953/2009) argued that some concepts don’t have necessary and sufficient conditions but rather, indeterminate ‘family resemblances.’ It could be argued, however, that if the attributes of a term can never be clearly boundaried (for example, ‘game’), it is not a concept and so not particularly useful for theory development or research.

Problems with concepts in applied psychology research

The socially constructed nature of concepts makes them susceptible to problems of epistemological detachment from ontological causal patterns. Concept analysis attempts to address specific conceptual problems including reification, vagueness and ambiguity, which are considered next.

Reification

Concepts are linguistic products of human experience and sociological, historical and political forces. Reification occurs when conceptual entities are imagined to be ontological entities that then enter the canon of ‘core knowledge’ (Thompson Citation2011; Adams & Markus, Citation2001). Professional interest is a powerful social force. Concepts that encapsulate psychologist knowledge, competence and activities are legitimated in the service of professional priorities, then treated in theory, research and practice as facts of life (Habermas Citation1987; Pilgrim Citation2016, Citation2019). An example of concept reification in the service of professional power is use of the adjective ‘vulnerable’ in health and social care to describe people at risk of harm (UK Government Citation2022). ‘Vulnerable’ means an acquired susceptibility to harm. But the term is used by some healthcare authorities to describe a disadvantaged state of being, without clear definitional guidance or measurement. This sets the stage for professional presumption that ‘vulnerability’ is an inherent personal characteristic that attracts abuse or neglect. Labeling a person 'vulnerable' can in effect inadvertently blame them of weakness. It reproduces professional blindness to powers, policies and people responsible for creating and replicating structural inequalities, in a manner likened to ‘scientific racism’ (Munari et al. Citation2021, 197). Its use can also imply that those not classed ‘vulnerable’ are immune to abuse and neglect, or are not worthy of statutory protections. Health and social care professionals may uncritically apply the ‘vulnerable’ label when not proficient in apprehending linguistic forms of social injustice. Misuse of the ‘vulnerability’ concept may be a result of inadequate conceptualisation of social harm, or blindness to power-systems that cultivate harm (Miller Citation1990; Pemberton Citation2015); or insufficient health professional training in taking action on social determinants of health (Andermann Citation2016). Katz et al. (Citation2019) used critical discourse analysis (which shares similarities with concept analysis, as I discuss later in this article) to scope professional literature using the term ‘vulnerable.’ They concluded that the term’s ‘vagueness serves the political function of obscuring power relationships and limiting discussion of transformational change’ (p.601). The problem of concept vagueness is discussed next.

Vagueness

Vague concepts are highly generalised and have unclear or porous meaning boundaries. Their component attributes (or denotations) may vary by context or theorist. ‘Therapeutic alliance’ is a vague concept. While generally taken to mean the collaborative, trusting relationship between a therapist and the person they are working with, ‘therapeutic alliance’ has had a multitude of definitional components attributed by different theorists over time. For example, Luborsky (Citation1976) suggested it includes the patient’s perception of therapist supportiveness and shared therapeutic responsibility. Bordin (Citation1979) proposed it comprises good personality fit between therapist and patient, agreement on goals, and therapist assignment of vividly relevant tasks. Pinsof (Citation1988) suggests it is the constellation of relational alliances in a group context (Ardito and Rabellino Citation2011). These definitions tend not to describe what ‘therapeutic alliance’ isn’t (Horvath Citation2018). Woolly definitional margins and indeterminate attributes make a concept a troublesome research entity.

Ambiguity

Ambiguous concepts can be interpreted in more than one way; or may have different uses or interpretations within the same field or discipline (Sartori Citation2009). An ambiguous concept in clinical psychology is ‘conceptualisation.’ It can mean the process of delimiting the observable characteristics of terms to be used in research; and it can also mean ‘formulation,’ which involves describing and explaining the antecedents and consequences of a life-problem someone wants to resolve with therapeutic assistance (Dudley, Kuyken, and Padesky Citation2011). Another ambiguous concept is ‘intelligence,’ which has multiple domains of meaning, including ability to learn; ability to apply knowledge to control or interact with the environment; propensity to think and communicate in abstract terms; mental acuity; capability for self-awareness; facility for emotional and relational attunement; or talent for complex problem-solving. It can also refer to information concerning a threat or enemy. The referent of an ambiguous concept must be parsed before the concept can be an effective research denotation.

Concept analysis, as I discuss next, is intended to tackle these and other types of concept inadequacy, to improve their use as theoretical and objective research tools.

Concept analysis as ‘pre-search’

The early stage of designing any qualitative or quantitative psychology study requires precise and unambiguous definition of concepts under investigation. The particular definitions used will affect participant recruitment, measures used, questions asked, and outcome (Chambliss and Schutt Citation2013). Sometimes one cannot find a well-boundaried definition for a concept one wants to research, which is a problem that turns to opportunity with concept analysis. Qualitative concept analysis as ‘presearch’, helps to illuminate or evolve concept definition and structure. It can also highlight where a new or reformed concept might better serve theory and practice, which in turn, opens new lines for scientific enquiry.

Take for example nursing researchers Knafl and Deatrick’s long-term ‘rewarding adventure in knowledge development’ (Citation2008, 415) around understanding families’ responses to managing their child’s chronic illness. Concept analysis method was applied to the under-defined term ‘normalization’ (Knafl and Deatrick Citation1990) coined by Davis (Citation1963) to describe how families of children with polio incorporate the illness into their interactional life. This study (Knafl and Deatrick Citation1990) involved synthesising findings from a focussed literature review with participant quotes from a related qualitative study (Knafl et al. Citation1987, Citation1996). The concept was reformed as ‘family management style.’ The family management style model was then refined to a more elaborate meaning framework with a multidimensional process diagram (Knafl and Deatrick Citation2003). From 2008 to 2011, a psychometrically sound measure of the family management styles framework was developed (Knafl et al. Citation2011; Knafl, Deatrick, and Gallo Citation2008, Citation2011). By 2021 multiple studies using the framework and measure had been published in USA, Canada, Thailand and Brazil (Knafl et al. Citation2021). This admirable concept-driven programme of research and practice application began with concept analysis. It also illustrates the importance of researchers building upon findings from concept analysis with dedicated intent to advance theory and practice (Hupcey and Penrod Citation2005).

Concept analysis traditions

Empirical concept analysis research methodologies have been employed in nursing scholarship (e.g. Rodgers Citation2000); political science (e.g. Collier and Gerring Citation2009); sociology (e.g. Fredericks and Miller Citation1987); gender studies (Goertz and Mazur Citation2007); and cognitive science (e.g. Fauconnier and Turner Citation1998; Mahon Citation2015). While each discipline has its own philosophical and ontological paradigms surrounding the nature of concepts and the purpose of concept analysis, all aim to enhance definitional specificity and understanding of the purposes and contexts in which a concept is used. All use a series of interpretive stages and analytic techniques, with the aim of contributing to the development of scientific literature surrounding the concept.

Reformative Concept Analysis (RCA), described in more detail below, is a novel methodological approach developed for applied psychology research. It systematically compares findings from literature review with qualitative reports of uses, purpose and/or definitions of a vague or ambiguous concept used within the professional discipline, with the aim of improving its stipulative definition, in other words, offering a more technically robust explanation of its meaning; or potentially developing a new term with a clearer connotation. RCA is informed by aspects of concept analysis techniques used in nursing and political science, two disciplines with well-developed concept analysis traditions that lend themselves to adaptation for applied psychology research. We will next look at influential aspects of concept analysis developed for nursing and political science, as well as their strengths and weaknesses from an applied psychology perspective.

Concept analysis in nursing

Nursing scholarship has developed a number of related concept analysis methods since the 1970s. These include, but are not limited to, the ‘Wilson method’ (Walker and Avant Citation2010; for a worked example see McVey’s Citation2023 concept analysis of ‘telenursing’); the ‘evolutionary method’ (Rodgers Citation2000; for a worked example see Connor et al.’s 2023 concept analysis of ‘clinical judgement’); and the ‘hybrid model’ (Schwartz-Barcott and Kim Citation2000; for a worked example see SadatHoseini et al.’s (Citation2023) concept analysis of ‘healing’). These approaches use literature review to identify a ‘model’ or ‘exemplar’ case that ‘absolutely reflects an instance of the concept’ (Schwartz-Barcott and Kim Citation2000, 140) and proves its defining criteria. The ‘hybrid’ approach triangulates literature analysis with concurrent fieldwork such as participant observations or in-depth interviews undertaken with people for whom the concept is a well-known experience.

Rather than seeking a ‘model’ case, ‘principle-based’ concept analysis (Morse et al. Citation1996; Penrod and Hupcey Citation2005) aims to clarify the concept’s structural features including definition, characteristics (necessary attributes), boundaries (inclusion and exclusion criteria), preconditions (influential preceding phenomena) and outcomes (consequences following an incidence of the concept) (Morse et al. Citation1996). Following this process four principles are applied by Penrod and Hupcey (Citation2005) to appraise the relevance of the concept’s representation in relevant literature, including epistemological clarity of definition and differentiation from similar concepts; its pragmatic usefulness as a research entity; linguistic consistency and fit in various contexts; and logical stability of its boundaries when placed with other concepts in a theoretical framework. More recently Smith and Mörelius (Citation2021) presented a detailed phased approach to conducting ‘principle-based’ CA including a screening tool for assessing the concept’s appearance in research articles against these relevance criteria. Hupcey and Penrod (Citation2003) describe how inductive validity can be strengthened in principle-based concept analysis through comparisons of templates of conceptual structural features derived from different bodies of qualitative and/or quantitative data. Hupcey and Penrod subsequently asserted however that concept analysis should deal only with ‘scholarly works not creative imagination, art forms, fiction, interview data,’ which they opined do not contribute to a ‘best estimate of probable truth’ (Hupcey and Penrod Citation2005, 205). This later injunction against use of qualitative interview data distinguishes ‘principle-based’ CA from Parse’s ‘concept inventing’ (Citation1990, Citation1997) which is a philosophical, creative method that interprets concept meaning from participant interviews, professional literature, and researcher reflections on art, photography and music.

Strengths and limitations of nursing CA from an applied psychology perspective

Strengths

A strength of the ‘hybrid’ approach is its triangulation of analyses of published research literature with participant experiential narratives. In some studies, this might help to balance professional partiality in literature-only data sources. A strength of ‘principle-based’ CA is its application of structural components including ‘preconditions’ and ‘outcomes’ to illuminate the function of agentic concepts that appear in causal processes. Agentic concepts such as ‘resilience,’ self-efficacy,’ and ‘autonomy’ refer to a person’s capacity to act, make choices or interact with their environment, and are particularly relevant in psychological healthcare.

Limitations

Nursing concept analysis methods that aim to describe a ‘model case' point to a positivist assumption that researchers possess epistemological authority to decide what constitutes an ideal example. This seems to defeat the purpose of critically analysing the concept’s meaning, and risks replicating professional blind spots. In any case, it can be argued that there are no ‘real life’ examples of ideal types (Goertz Citation2006). Furthermore, these approaches do not explain researchers’ recourse if a ‘model’ case is not found.

‘Principle-based’ concept analysis is positioned as an interpretive approach that qualitatively summarises findings from others’ research. Its positivist pursuit of inductive validity (Hupcey and Penrod Citation2003) may require reframing in psychology-focused qualitative research as more relativist pursuits of authenticity and rigour in relation to qualitative quality (Maxwell Citation1992). Given the mutual embeddedness of concepts and theory, considering concept analysis only useful for inductive theory-building research overlooks its functionality as deductive theory-clarifying research.

The ‘hybrid’ approach (Schwartz-Barcott and Kim Citation2000) positions meanings created from literature review as the primary working definition against which fieldwork data are triangulated. This activity privileges professional knowledge. Depending on study aims, the researcher may wish to invert the ‘hybrid’ approach and prioritise lived or lay experience when this data source could provide a more critically salient primary working definition against which to compare the concept's usage in professional literature.

A general limitation of nursing concept analysis is a lack of convention around presentation of results. A table of defining attributes may (e.g. Olsson et al. Citation2003) or may not (e.g. Ridner Citation2003) include source articles. Where diagrams of possible causal processes are included, these tend to be thinly detailed and simplistic (see for example Burrows’ (Citation1997) process of ‘facilitation’).

The next section reviews Sartori’s (Citation1984, 2009) approach to concept analysis in political science. This is similarly followed by a summary of its strengths and limitations from an applied psychology perspective.

Concept analysis in political science

Sartori (Citation1984, Citation2009) describes a form of concept analysis that is concerned with mapping, defining and improving the quality of concept structure using ‘ladders of abstraction’ (sometimes called ‘ladders of generality’, e.g. Goertz Citation2006). Concepts can be understood as pyramid-shaped meaning frameworks with the most abstract term on top and a range of definitional terms ensuing beneath; then each of these terms issuing yet more granular meanings on lower levels of the hierarchy.

A concept’s intension (core definition or connotation) is the aggregate of its associated characteristics or properties. Its extensions (or denotations) are all the groups, cases, or types of phenomena that issue from the intension. A highly generalised intension, with few inclusion and exclusion criteria, will allow many extensions (‘cases,’ or ‘types’). On the other hand, an intension with a more detailed, exclusive definition will allow fewer demonstrative cases.

Sartori’s concept analysis method involves three tasks. The first, reconstruction, involves making an intelligible meaning diagram or template from a detailed analysis of the concept’s history and current state in academic literature. The diagram should include denotative labels for clusters of included phenomena organised of over distinct levels of abstraction from single intension (the concept label under investigation) down to a number of denotation labels which in turn become intensions for further, yet more detailed denotation labels.

The second task is forming the concept which is describing the ‘apt and sufficient properties for marking [its] boundaries’ (Sartori Citation2009, 123), and deciding which phenomena and denotations probably are, and are not, part of the concept. If necessary, this stage also involves choosing a new concept label that clearly differentiates it from related terms.

The final task, reconceptualization creates an empirically useful re-definition of the concept. Although Sartori does not elaborate this stage, reconceptualization can kick-start long term research work of the type exemplified by Knafl and Deatrick described above.

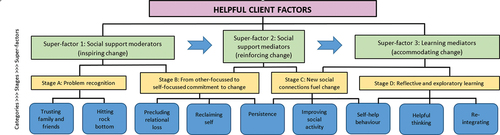

By way of example, Vermes (Citation2018) created a concept reconstruction (hierarchy of abstraction) for the vague ‘client factors’ concept within the ‘common factors’ theory that different types of therapy have common elements that account for why they produce generally equivalent results (Castonguay and Beutler Citation2006; Frank and Frank Citation1993; Wampold and Imel Citation2015). Vermes' (Citation2018) concept hierarchy of‘client factors’ found in research literature that influence positive outcome in psychological therapy, is shown in .

The intension of the highly abstract term ‘helpful client factors’ has no defined exclusion criteria in associated literature, so admits a wide definitional system with many extensions, including all personal and extratherapeutic factors that influence whether and how a person can achieve desired change with therapeutic help. Meaning is first organised into three slightly less abstract ‘super-factors’ (social support moderators and mediators; and learning mediators); which are then further broken down to four ‘stages of change’ which have explanatory power in relation to therapeutic change process theories. Each ‘stage’ has more detailed denotations that differentiate factors that belong to that stage from those that don’t. Denotations for ‘Stage A: Problem recognition’ include the categories ‘trusting family and friends’ and ‘hitting rock bottom.’ The intension below each category includes highly detailed and differentiated types of experiences and activities (not shown in the figure) gleaned from qualitative and quantitative research data.

Not unlike Penrod and Hupcey’s four criteria for appraising concept relevance in principle-based concept analysis, Gerring (Citation2012) developed seven criteria for assessing concept adequacy that can be applied to Sartori-informed concept analyses. These are described in stage 8 of the methodology described later in this article.

Strengths and limitations of Sartori-informed CA from applied psychology perspective

Strengths

The Sartori method is indicative rather than prescriptive, offering the researcher freedom to adjust their process to specific contexts. It flexes to different research epistemologies and ontologies. It also allows the researcher to move between deductive activities (e.g. framing a research question around known concept inadequacies) and inductive activities (e.g. creating a meaning framework based on analysis of participant interviews).

Limitations

While Sartori values qualitative research particularly for its power to discriminate and differentiate conceptual meanings, the ‘ladder of abstraction’ method (Citation2009) does not consider overlaying, comparing or contrasting two or more frameworks for the same concept created from different data sources (e.g. published research and qualitative interviews). He does not discuss how concept analysis findings can inform theory. Also, Sartori is fairly uninformative about how to present hierarchy diagrams. After all the work of analysis, a small table (see for example Kurtz’ Citation(2009) conceptual dimensions of ‘peasants’); a minimal tree diagram (see for example Gerring’s Citation2012 taxonomy of ‘polity’) or no illustration at all (e.g. Muhammad and Aboya’s Citation2023 concept analysis of ‘deliberative democracy’) don’t help the reader appreciate a concept’s complex semantic pedigree or domains of meaning.

How concept analysis can address conceptual problems in applied psychology

The main points derived from the preceding observations of strengths and limitations of nursing and political science concept analysis methods help inform a methodological approach suitable for applied psychology. These points include: are:

Openness to ontologies and epistemologies that accommodate a deductive theory-testing analysis is required, as well as those that support inductive theory building analysis, to accommodate a range of research questions

Replication of professional bias around concept meaning may be reduced by triangulating research-based analysis with direct qualitative narratives of lived experience

Depending on the conceptual context and research question, triangulated templates derived from lived experience data may form the primary definitional framework against which the research-derived template is shaped and compared

Results may be presented as a detailed concept framework over several levels of abstraction and denotation. Structural components (e.g. preconditions, outcomes) may be included with respect to the process-oriented and resource-determined nature of psychological change over time

Tools for assessing the quality of research chosen for analysis are required

Criteria for assessing the utility of the reformed concept are required

RCA is a modified form of concept analysis that accommodates these requirements. It is suitable for analysing and reforming potentially useful but otherwise vague, ambiguous or taken-for-granted terms in applied psychology research. RCA goes further than previous forms of concept analysis by explicitly developing detailed illustrative frameworks from the findings that typically give prominence to lived experience of phenomena integral to the concept. RCA also includes critical analysis of the findings, for example, revelation of otherwise obscured operation of power in the definition or use of a concept in professional discourse. In this way RCA shares a superficial similarity with discourse analysis (e.g. Potter and Wetherell Citation1987). However, while discourse analysis may be used to explore sociological inequities in identities, cultures and social representations embedded in language, concept analysis primarily aims to improve clarity and depth of understanding of terms used within a professional discipline, and to improve concept performance in both reflecting and shaping knowledge. RCA for applied psychology is particularly focussed on understanding how lived experiences are included or obscured by professional concept usage purporting to encapsulate the phenomenon.

Reformative concept analysis (RCA)

RCA is an original approach that takes influence and elements from nursing concept analysis including ‘principle-based’ (Penrod and Hupcey Citation2005) and ‘hybrid’ approaches (Schwartz-Barcott and Kim Citation2000); and from Sartori’s ‘ladder of abstraction’ approach. The distinguishing combination of researcher activities in RCA includes (a) typically prioritising a thematic hierarchy framework derived from analysis of lived experience over the framework resulting from a similarly produced professional literature review framework; (b) creating detailed illustrative framework diagrams over several layers of abstraction; and (c) providing a defining statement of necessary and sufficient conditions that encapsulates the concept’s meaning and boundaries, which may in turn lead to potentially suggesting a change to concept labelling where appropriate to improve its clarity. The results should also offer a historically informed assessment and critique of the concept’s current operation in research literature and lived experience, and a granular definition that opens opportunities for further research into its component phenomena.

Next, suggestions are given here for framing research aims and questions, and choosing appropriate ontology and epistemology for RCA. Then, eight stages for carrying out RCA are described. Steps for ensuring qualitative rigour are suggested. Any reader wishing to use RCA is advised that the indicative methodological stages presented here should be undertaken after reading some of the classic concept analysis texts referenced in this article. The researcher should also feel free to adapt RCA stages to suit the specificities of the research aim and questions. Applied psychology students using RCA for thesis research may be assigned academic supervisors and examiners who are unacquainted with concept analysis methods. These students may be pressed harder for a justification of their choice of concept analysis than they might for a using a less suitable qualitative method that their supervisors are nonetheless more familiar with. It is worth arguing for the specific utility and suitability of concept analysis if the research aim and questions are best served by the method. These are discussed next.

Research aim and questions

An RCA preliminary literature review sets the stage for the research aim. Scoping relevant historic, theoretical and professional contexts surrounding the concept use should problematise its definition, and explain why RCA is necessary to clarify its boundaries and connotations, preferably with respect to a discipline-specific area of research analysis (e.g., therapeutic outcome). RCA can also be used to create new concepts, for example where the existence, meaning or relationship of a set of phenomena needs to be encapsulated in an abstract term for admission to future scientific enquiry.

Research questions

Research questions amenable to RCA include (but are not limited to):

Can more specific definitional attributes or connotations of this concept be determined? If so, what are they?

How does this concept’s use in quantitative or qualitative research map onto lived experience? How can lived experience inform this concept’s use in professional contexts?

What is this concept’s structure (hierarchy of abstraction and/or preconditions, characteristics and outcomes)?

How does this concept operate in clinical practice? How can this inform theory?

What is this concept’s role in a theoretical causal pathway or process?

Does this concept’s operational function match its theoretical function?

Does a concept need to be identified for this phenomenon or process that has no currency in professional discourse?

Could this concept be renamed to more clearly point to its meaning?

How might general professional conviction surrounding the meaning of this concept give way to probing around its use, particularly where it may operate to promote power interests?

Ontology and epistemology

RCA is amenable to researcher ontological and epistemological positions that require reflexive commitment to challenging unequal power relations between producers of knowledge and those with subaltern experiences (Albert et al. Citation2020).

Ontology

Sartori notes, ‘the argument that “real definitions” seek the “essence” of things hits on a straw man … All definitions are nominal in that they relate to the concepts expressed by words, even though some may be called “real” in the sense that they employ observational terms and are conceived as pointers to “objects”’ (2009, p. 89). In RCA a distinction is made between words as socially constructed epistemological vessels, and the objects, experiences, forces and effects for which they act as symbolic representations. Critical realist ontology provides a useful philosophical framework for RCA in that it clearly distinguishes the nature of reality as partially (or largely) beyond human knowledge and language, from our epistemological knowledge of reality, which is freighted with theories that attempt to explain how and why things happen. Critical realism accommodates social relationships and political contexts as significant causal influences. Critical realist research (as described by Fletcher, Citation2017) is flexibly deductive in that it commences with research questions derived from shortcomings identified in existing theory; relies on interpretive extraction of themes, meanings and trends in qualitative and quantitative data gathered specifically for this study; re-describes the interpreted findings in relation to the originating theory; and investigates the social context within which causal powers or processes take effect (Risjord Citation2009). These thoughts aside, it is the researcher's responsibility to select an ontology that best suits their research question.

Epistemology

Epistemology in RCA should openly acknowledge researcher situatedness in time, culture, discipline and research aims. The concept analyst might consider adopting a specific underpinning critical standpoint (for example, feminist, see Cohen et al. Citation2022; Wuest Citation1994) that is evident throughout decision-making, analysis and write-up.

In a hierarchy of abstraction, the most specialist knowledge of a concept’s denotations is located in the least abstract levels of the framework. Refining knowledge at these levels requires the researcher to gather direct evidence from people with expert knowledge, which is why RCA includes qualitative interview or other narrative data. Choosing appropriate epistemic environments and processes for participant recruitment is an important early consideration.

Any RCA will be limited by the scope of qualitative and qualitative data used, and by researcher interpretive skill and standpoint. Concept analyses for this reason are best repeated with data sets from different contexts, then compared with previous iterations. Assertions about contribution to knowledge from concept analysis should be made in light of language fluidity across time and context, and should remain mindful of the impossibility of capturing all possible categories of meaning for the concept in question.

RCA method overview

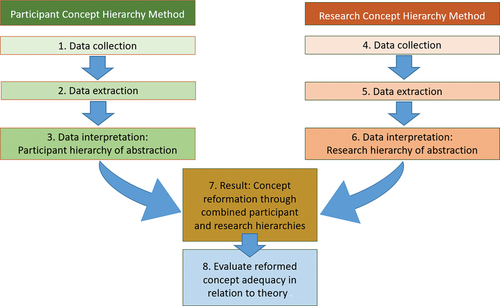

RCA is carried out over eight stages including participant data collection, data extraction and interpretation to a hierarchy of abstraction; published literature data collection, data extraction and interpretation to a framework whose structure is informed by the participant data hierarchy; comparison and combination to one concept framework with a reformed definition (and possibly name) that captures the boundaries of the concept; and finally, evaluation of the adequacy of the reformed concept in relation to relevant theory. A diagrammatic summary of the eight stages is shown in .

Stage 1 – Participant recruitment, interviews and transcription

Once all required institutional ethical approvals are obtained, participant recruitment sites should be carefully selected to locate people capable of sharing diverse understandings and experiences of the concept or research question (Morrow and Smith Citation2000). Aiming for 12 participants is recommended (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson Citation2006). The resulting interview data set should be large enough to capture a breadth of meanings but not so large as to be unduly repetitious (O’Reilly and Parker Citation2012). A semi-structured interview format of 45–60 minutes provides flexibility for participants to expand upon topics of relevance to them, while affording the researcher freedom to tailor their responses to the participant (Kvale Citation2007). The interview should comprise a few simply-framed questions that are tightly focused on the aim of the study (Agee Citation2009). Verbatim transcription is best done soon after the interview by the researcher who carried out the interview. Use of transcription software omits essential early stages of the researcher's data familiarisation and analysis, and is not recommended.

Stage 2 – Interview data extraction, organising and cleansing

While transcribing, it is useful to keep a separate summary of each participant’s narrative to capture possible denotations around the concept. The data extraction spreadsheet is commenced during transcription with denotations listed horizontally, and levels of abstraction vertically with most abstract near the top, least abstract towards the bottom. The spreadsheet is organised and re-organised over repeated readings of the transcripts into increasing levels of abstraction back to the concept in question, starting at the least abstract level, as follows:

Elements are mildly abstract, person-level, labelled groupings of direct experiences associated with the concept or research question. Elements are built from, and illustrated by, non-abstract participant quotes. Where possible, several quotes from one or more participants should illustrate each element. Element labelling represents the first stage of interpretation, and may be revised several times over the course of data extraction to best capture meaning. While concept analysis is an interpretive activity, interview data is taken at ‘face value’ as honest explanations of experience and knowledge. The researcher should minimize seeking, interposing or inventing meaning beyond what participants say.

Once all relevant elements have been harvested from the interview data, they are then organised under a smaller number of more abstract category labels. Appropriate labels for patterns of meaning at the categorical level become clear only after some time working with the data. The position of associated elements may be adjusted as analysis continues.

Categories then require further researcher interpretation to causal or process theories to sort them under single (or very limited number of) superordinate label(s), avoiding clinical jargon where possible. An intermediate subordinate level of abstraction between categories and superordinate labels may be included where needed.

Data cleansing

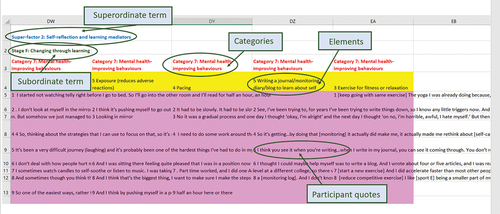

Once the first draft of the spreadsheet is completed, the entire corpus is reviewed at the elemental level by printing out the labelling rows (quotes, elements, categories, sub- and superordinate terms). Pen, scissors and sticky tape may help with data cleansing, which involves collapsing duplicate elements; re-positioning those that seem to be under the wrong label; renaming those requiring clearer labels; and deleting elements which are not precisely evidenced by participant data, or not closely related to the research question. Precise labels that readily evoke meaning should be used. Neighbouring terms within the hierarchy should relate well. Synonymies should appear neither laterally nor vertically in the hierarchy. (from Vermes Citation2018) shows a portion of an interview data extraction spreadsheet following data cleansing, with levels of abstraction labelled.

Figure 3. Portion of an interview data extraction spreadsheet following data cleansing, with levels of abstraction labelled (from Vermes Citation2018).

Stage 3 – Participant data interpretation to hierarchical diagram

Interpretation from the data extraction spreadsheet to a suitable diagrammatic form is a creative step that takes time and thought to condense findings while retaining informative detail. The ‘shape’ and ‘story’ suggested by the spreadsheet should be considered in relation to relevant theory. The researcher also looks for aspects of the data that might extend or inform theory. Participant data may include inverse, or negative elements of the concept. Participant data is is likely to contain elements that are not observed in research. The researcher must decide if these conceptual ‘shadows’ should be included in the conceptual diagram on the basis of their value to the reformation. Design software can be used to create the hierarchy diagram, although word processing tools suffice. Encouragingly, Sartori leaves organising frameworks ‘to the perceptiveness and ingenuity of the analyst’ (Citation2009, 116).

Stage 4 – Study selection

Study selection takes place over four phases which can be represented on a PRISMA-style chart (PRISMA Citation2020), although concept analysis review is selective rather than purely systematic (Rodgers Citation2000).

Article search and identification

Sartori (Citation1984) calls the researcher to collect a ‘representative set of definitions’ from ‘pertinent literature’ and to strive for ‘historical depth’ (p. 41). Because ‘representativeness’ has elsewhere been proscribed as too difficult to prove in qualitative research (Barbour Citation2001), a purposive dataset should be delimited by search terms devised to locate studies from the past fifty years or so in databases likely to yield informative quantitative and qualitative articles about component attributes, operations, or theoretical functions of the concept in question. Highly abstract concepts may have obvious (and perhaps also some tentative) definitional components to include in the search. Articles from reference lists in relevant meta-analyses and text book chapters may be included. Organisational reports, grey literature or non-peer-reviewed sources may be justified for inclusion.

Screening

Title and abstract screening are carried out on search results. Studies remaining for full text review are not typically subject to critical appraisal given the scoping nature of concept analysis (see Peters et al, Citation2020 for more detailed guidance on scoping reviews).

Eligibility

The researcher is advised to use generic quality control criteria for systematic reviews (e.g. Rutter et al. Citation2010); and bespoke inclusion criteria shaped by the research question. Exclusion criteria (which may become clearer as candidate studies are read) should be detailed on the PRISMA-style chart.

Data set adequacy

Penrod and Hupcey (Citation2005) note single-researcher concept analysis studies have included 83 and 107 studies. Rodgers (Citation2000) notes that an effective concept analysis may include anywhere from 30 to over 4,000 articles. Bearing in mind both recommendations are for studies that do not triangulate qualitative interviews, overall dataset adequacy is indicated by the study’s capacity to offer a detailed evidence-based hierarchy. Study characteristics should be tabulated.

Stage 5 – Research data extraction

Included studies are entered into rows on a summarisation spreadsheet. Column labels include study data features relevant to defining and operationalising the concept, such as research questions, design, analysis, information about participants, and, particularly importantly, a column for each of the key findings in relation to the concept. The number of findings columns may range from 20 for a mildly abstract concept to 45+ for a highly abstract concept with an extensive range of candidate denotations.

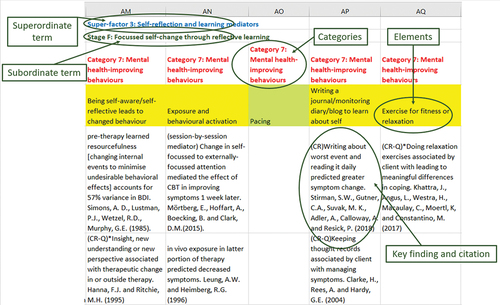

Once all articles have been summarised, key findings for each study are printed out, cut into tags, and sorted into elements on a large sketch of the participant-informed concept hierarchy framework. In this way the participant framework is privileged for interpretation of concept meaning (a researcher who needed to privilege research findings would swap stages 4, 5 and 6 with 1, 2 and 3). It may be that the research findings fit some but not all the elements found in the qualitative data; and/or that new elements and categories were found that were not present in the interview data. Tags are then entered into the data extraction spreadsheet (started in stage 2) on a new sheet laid out with identical superordinate, subordinate, categorical and elemental labels. Any new elements can be added to the spreadsheet. Findings and study citations are entered to evidence elements in the same way that participant quotes did on the first sheet. (from Vermes, Citation2018) shows an example portion of the research extraction spreadsheet that corresponds with the interview data spreadsheet portion shown in .

Figure 4. Matching portion of the research extraction spreadsheet (from Vermes Citation2018).

Stage 6 - Research data interpretation to hierarchical diagram

The research-informed concept framework diagram is created in the same format as the participant-informed framework, including any additional elements and categories not matched by participant data. The resulting diagram should readily lend itself to comparison and combination with the interview findings diagram.

Stage 7 – Concept reformation

Concept reformation involves combining the participant and research hierarchies into a single framework that clearly colour-codes aspects found in (a) both data sets, and those found only in (b) the participant data set or (c) the research data set. A defining statement of necessary and sufficient conditions that encapsulates the concept’s boundaries is provided. If called for, a new concept name can be mooted. Where the participant framework includes elements not found in the research framework, the researcher should consider if important lived experience elements of the concept have been overlooked in previous research, and provide further critical discussion around this. Alternatively, perhaps the search strategy inadvertently ruled out studies encompassing the missing phenomena, and the researcher should consider and discuss alternative approaches to finding the concept at play in more obscure sources or via more advanced search strategies. Where the research framework includes elements not found in the participant framework, the researcher should consider the significance of professional perspectives that may not be visible from a lived experience standpoint (see for example Morse Citation2000 on ‘denial’). Alternatively, it might be that the RCA interview questions inadvertently failed to elicit information about this conceptual aspect.

Stage 8 – Evaluating the findings: concept adequacy

In the discussion it may be useful to apply Gerring’s (Citation2012) seven criteria to evaluate adequacy of the reformed concept:

Causal utility – to what extent is the concept a useful component in a materially or socially mechanistic theory about the relationship between independent and dependent variables (or in qualitative terms, ‘change agents’ and ‘the changed/unchanged’).

Domain – what is the scope of ‘language communities’ the concept can be used in, for example, lay or academic audiences; or ‘cultures’ within a discipline.

Fecundity – how well does the concept explain circumstances, events, intentions and reactions over a set of cases with richness and depth. Good concepts ‘reveal the structure within the realities they attempt to describe’ (Gerring Citation2012, 125).

Differentiation – how clear-cut is the concept from contiguous or similar concepts

Resonance – does the concept use familiar terminology and meanings.

Consistency – is the concept used with all the same connotations in different empirical contexts.

Operationalisation – can the concept be easily observed and measured

Milevski (Citation2023), writing about defence and security concepts, suggests ‘strategic utility’ as another quality criteria for assessing how useful the concept is in practice, for example in guiding effective decision making, or in linking a wider system of theories. Strategic utility may be applied as an eighth quality criteria for concepts relating to clinical practice.

It is not necessary or possible for a freshly reformed concept to meet all the above criteria. For example, consistency of newly disambiguated concepts may only be assessed in future.

Rigour

Measures to ensure credibility and trustworthiness in RCA include sufficient raw data to evidence interpretations; data triangulation; participant reviews of transcripts and portions of the analysis; evidence of researcher reflexivity; and a detailed audit trail.

Considerations for the RCA discussion section

Besides providing detailed answers to the research questions, and critique of the adequacy of the reformed concept, areas for exploration in the discussion might include how aspects (or the entirety) of the reformed concept can inform, adjust or be accommodated into theory, practice and/or research. What has been overlooked about how this concept works in theory and practice? What can be learned about how causal relationships work within the concept’s structure, and between this and related concepts? Is RCA with different datasets now needed? What concept advancement research programme could ensue?

A drawback of RCA is resulting framework diagrams for particularly abstract or multipartite concepts may be too large or detailed to fit standard-size paper or journal format. However, this problem is outweighed by the educational value of seeing concept components and their relationships fully illustrated alongside the textual explanation.

Conclusion: How RCA might impact clinical practice and research

RCA extends the reach and function of concept analysis traditions by offering a method suitable for applied psychology research. As its nursing and political science precursors have done, RCA scopes and clarifies a concept’s usage context and/or the boundaries and content of its definition. However, RCA also highlights in graphic and descriptive terms how the concept might operate in lay (e.g. service user) experience in ways that are potentially overlooked, under-valued or misconceived in academic and professional theory, research or discourse. In this way, RCA offers a research pathway for grappling with epistemic injustice (see Fricker Citation2009). The directions RCA might be taken depends on the researcher’s aims and the nature of the concept, but may encompass some or all the following activities:

Creating alternative or refined labelling for the concept or its denotation

Identifying concept denotations previously not noticed as potentially relevant to psychological change process, recovery, or wellbeing

Developing observational and measurement criteria for previously under-researched conceptual denotations

Engaging in further theory development or practice-based research to understand the presence and role of the concept within mental and behavioural health change processes

Extending ‘received wisdom’ around concept meaning in theories of how psychological therapies work by foregrounding lived experience, while respecting empirical evidence

Valuing relevant lived experience in therapeutic conversations

An example of how RCA can impact clinical practice and research is taken from Vermes’ 2018 concept analysis of the ‘client factors’ concept in common factors theory. A client factor associated with positive change located at a relatively abstract level of the concept hierarchy is ‘improving social activity’ (see ). This connotation issues several further more concrete denotations including two that were given original labels by the researcher in an effort to create terms for previously unrecognised but potentially salient phenomena in client active change processes (not shown in due to detail). The first new term, ‘proximalising’ describes how people might move geographically closer to well-loved family, friends or partner (‘my blood’) or to places of personal significance (‘my roots’) to improve or repair their sense of belonging. The second new term, ‘distalising’ is the converse action of taking important steps to move away from unhelpful relationships or places associated with bad memories. Corollaries of ‘proximalising’ and ‘distalising’ were not found in the comparative research framework, suggesting that while an individual's motivations to move their home to improve social milieu may be relevant to mental health change processes, the significance of this may not be noted as worthy of research investigation from clinician or academic standpoints. In clinical practice, therapeutic conversations concerned with ‘proximalising’ and ‘distalising’ can open important space for making sense of the significant impact of migration and other relocations on client, family and community wellbeing and identity. In research, ‘proximalising’ and ‘distalising’ as positive change-salient concepts could be further developed through, for example, task analysis methods including discovery, hypothesising and validation, and dynamic modelling phases (e.g. Pascual-Leone, Greenberg, and Pascual-Leone Citation2009). These new words 'proximalising' and 'distalising' are baroque and clumsy. In terms of concept adequacy, they not resonant. They would first need to be rephrased to be more easily understood.

In conclusion, RCA is a ‘pre-search’ qualitative methodology that seeks to interrogate and carefully illustrate the structure and meaning of taken-for-granted concepts in applied psychology practice and research. RCA investigates a concept’s utility in describing experiences relevant to mental health treatment and change processes, by respecting and giving salience to personal experiential accounts of the concept as well as professional understandings of its meanings. RCA lends itself to researcher reflexivity and critical social constructivist epistemological standpoints. The RCA researcher is encouraged to use this method as a sensitising tool for illuminating colonising effects of professional power in applied psychology terminology. Further studies using RCA are needed to explore its potential uses and limitations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gabriel Wynn

Gabriel Wynn is Competence Development Lead for the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP). She also works as a counselling psychologist with Greater Manchester NHS. This article is derived from her doctoral research on the meaning of ‘client factors’ in common factors theory, in partial completion of the Doctorate in Counselling Psychology programme at University of Manchester, UK.

References

- Adams, G. and H. R. Markus. 2001. Culture as patterns: An alternative approach to the problem of reification. Culture & Psychology 7 (3):283–96. doi:10.1177/1354067X0173002.

- Agee, J. 2009. Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 22 (4):431–47. doi:10.1080/09518390902736512.

- Albert, K., J. S. Brundage, P. Sweet, and F. Vandenberge. 2020. Towards a critical realist epistemology? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 50 (3):357–72. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12248.

- Andermann, A. 2016. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal 188 (17–18):17–18. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160177.

- Ardito, R. B., and D. Rabellino. 2011. Therapeutic alliance and outcome of treatment: Historical excursus, measurements and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychotherapy 2 (270):1–11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270.

- Bandura, A. 1978. The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist 33 (4):344–58. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.33.4.344.

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

- Barbour, R. S. 2001. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal 322 (7294):1115–17. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

- Bordin, E. S. 1979. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 16 (3):252–60. doi:10.1037/h0085885.

- Burrows, D. E. 1997. Facilitation: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 25 (2):396–404. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025396.x.

- Castonguay, L. G., and L. E. Beutler. 2006. Common and unique principles of therapeutic change: What do we know and what do we need to know? In Principles of therapeutic change that work, ed. L. G. Castonguay and L. E. Beutler, 353–70. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Chambliss, D. F., and R. K. Schutt. 2013. Making sense of the Social World: Methods of investigation. 4th ed. London, UK: Sage.

- Chinn, P. L., and M. K. Kramer. 1994. Theory and nursing: A systematic approach. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book.

- Cohen, J. A., A. Hassan, K. Wada, and M. Suehn. 2022. The personal and the political: How a feminist standpoint theory epistemology guided an interpretive phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology 19 (4):917–49. doi:10.1080/14780887.2021.1957047.

- Collier, D., and J. Gerring, Eds. 2009. Concepts and method in social science. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

- Davis, F.1963. Passage through crisis: Polio victims and their families. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Dudley, R., W. Kuyken, and C. A. Padesky. 2011. Disorder-specific and trans-diagnostic case conceptualisation. Clinical Psychology Review 31 (2):213–24. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.005.

- Fauconnier, G., and M. Turner. 1998. Conceptual integration networks. Cognitive Science 22 (2):133–87. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2202_1.

- Fletcher, A. J. 2017. Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (2):181–94. doi:10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401.

- Frank, J. D., and J. B. Frank. 1993. Persuasion and healing: A comparative study. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Fredericks, M., and S. I. Miller. 1987. The use of conceptual analysis for teaching sociology courses. Teaching Sociology 15 (4):392–98. doi:10.2307/1317995.

- Fricker, M. 2009. Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Gerring, J. 2012. Social science methodology: A unified framework. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goertz, G. 2006. Social science concepts: A User’s Guide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Goertz, G. 2007. Politics, gender and concepts: Theory and methodology. Eds. Mazur, A.G., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18 (1):59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Habermas, J. 1987. Knowledge and human interests. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Horvath, A. O. 2018. The psychotherapy relationship: Where does the alliance fit? In Developing the Therapeutic Relationship: Integrating case studies, research and practice, ed. O. Tishby and H. Wiseman. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Hupcey, J. E., and J. Penrod. 2003. Concept advancement: Enhancing inductive validity. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 17 (1):19–30. doi:10.1891/rtnp.17.1.19.53168.

- Hupcey, J. E., and J. Penrod. 2005. Concept analysis: Examining the state of the science. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal 19 (2):197–208. doi:10.1891/rtnp.19.2.197.66801.

- Katz, A. S., B.-J. Hardy, M. Firestone, A. Lofters, and M. E. Morton-Ninomiya. 2019. Vagueness, power and public health: Use of ‘vulnerable’ in public health literature. Critical Public Health 30 (5):601–11. doi:10.1080/09581596.2019.1656800.

- Knafl, K., B. Breitmayer, A. Gallo, and L. Zoeller. 1987. How families define and manage a child’s chronic illness. NCNR funded research.

- Knafl, K., B. Breitmayer, A. Gallo, and L. Zoeller. 1996. Family response to childhood chronic illness: Description of management styles. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 11 (5):315–26. doi:10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80065-X.

- Knafl, K., and J. Deatrick. 1990. Family management style: Concept analysis and development. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 5 (1):4–14. doi:10.5555/uri:pii:088259639090047D.

- Knafl, K., and J. Deatrick. 2003. Further refinement of the family management style framework. Journal of Family Nursing 9 (3):232–56. doi:10.1177/1074840703255435.

- Knafl, K., J. A. Deatrick, and A. M. Gallo. 2008. Interplay of concepts, data and methods in the development of the family management style framework. Journal of Family Nursing 14 (4):142–428. doi:10.1177/1074840708327138.

- Knafl, K., J. Deatrick, A. Gallo, J. Dixon, M. Grey, G. Knafl, and J. O’Malley. 2011. Assessment of the psychometric properties of the family management measure. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 36 (5):494–505. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp034.

- Knafl, K., J. Deatrick, A. M. Gallo, and B. Skelton. 2021. Tracing the use of the family management style framework and measure: A scoping review. Journal of Family Nursing 27 (2):87–106. doi:10.1177/1074840721994331.

- Kurtz, M. J. (2009). Peasant: clarifying meaning and refining explanation. In Concepts and Method in Social Science: The Tradition of Giovanni Sartori, D. Collier and J. Gerring, 269–88. New York: Routledge.

- Kvale, S. 2007. Doing interviews. London, UK: Sage.

- Luborsky, L. 1976. Helping alliances in psychotherapy: The groundwork for a study of their relationship to its outcome. In Successful Psychotherapy. ed. J. L. Cleghorn, 92–116. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

- Mahon, B. Z. 2015. Missed connections: A connectivity-constrained account of the representation and organisation of object concepts. In The conceptual mind: New directions in the study of concepts, ed. E. Margolis and S. Laurence, 79–115. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Maxwell, J. A. 1992. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review 62 (3):279–300. doi:10.17763/haer.62.3.8323320856251826.

- McVey, C. 2023. Telenursing: A concept analysis. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 10–1097. doi:10.1097/CIN.0000000000000973.

- Milevski, L. 2023. What makes a good strategic concept? Comparative Strategy 42 (5):718–28. doi:10.1080/01495933.2023.2236493.

- Miller, A. 1990. Banished knowledge: Facing childhood injuries. London, UK: Virago.

- Morrow, S. L., and M. L. Smith. 2000. Qualitative research for counseling psychology. In Handbook of counseling psychology, ed. S. D. Brown and R. W. Lent, 199–230. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Morse, J. M. 2000. Denial is not a qualitative concept. Qualitative Health Research 10 (2):147–48. doi:10.1177/104973200129118291.

- Morse, J. M., J. E. Hupcey, C. Mitcham, and E. Lenz. 1996. Concept analysis in nursing research: A critical appraisal. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 10:257–81.

- Morse, J. M., C. Mitcham, J. E. Hupcey, and M. C. Tasón. 1996. Criteria for concept evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 24 (2):385–90. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.18022.x.

- Morse, J. M., and J. Penrod. 1999. Linking concepts of enduring, uncertainty, suffering and hope. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 31 (2):145–50. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00455.x.

- Muhammad, I., and A. K. Aboya. 2023. Conceptual analysis of deliberative democracy: A Sartorian perspective. Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 6 (2). doi:10.52337/pjia.v6i2.867.

- Munari, S. C., A. N. Wilson, N. J. Blow, C. S. E. Homer, and J. E. Ward. 2021. Rethinking the use of ‘vulnerable’. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 45 (3):197–99. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.13098.

- Olsson, C. A., L. Bond, J. M. Burns, D. A. Vella-Brodrick, and S. M. Sawyer. 2003. Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of Adolescence 26 (1):1–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00118-5.

- O’Reilly, M., and N. Parker. 2012. ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research Journal 13 (2):1–8. doi:10.1177/1468794112446106.

- Paley, J. 1996. How not to clarify concepts in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 24 (3):572–78. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.22618.x.

- Paley, J. 2021. Concept analysis in nursing: A new approach. Abingdon, Oxfordshire UK: Routledge.

- Parse, R. R. 1990. Parse’s research methodology with an illustration of the lived experience of hope. Nursing Science Quarterly 3 (1):9–17. doi:10.1177/089431849000300106.

- Parse, R. R. 1997. Concept inventing: Unitary creations. Nursing Science Quarterly 10 (2):63–64. doi:10.1177/089431849701000201.

- Pascual-Leone, A., L. A. Greenberg, and J. Pascual-Leone. 2009. Developments in task analysis: New methods to study change. Psychotherapy Research 19 (4–5):527–42. doi:10.1080/10503300902897797.

- Pemberton, S. 2015. Harmful societies: Understanding social harm. Briston, UK: Bristol University & Policy Press.

- Penrod, J., and J. E. Hupcey. 2005. Enhancing methodological clarity: Principle-based concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 50 (4):403–09. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03405.x.

- Peters, M. D. J., C. Marnie, A. C. Tricco, D. Pollock, Z. Munn, L. Alexander, P. Mcinerney, C. M. Godfrey, and H. Khalil. 2020. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18 (10):2119–26. doi:10.11124/JBIES-20-00167.

- Pilgrim, D. 2016. Diagnosis and formulation in medical contexts. In The handbook of counselling psychology, ed. B. Douglas, R. Woolfe, S. Strawbridge, E. Kasket, and V. Galbraith, 169–84. 4th ed. London, UK: Sage.

- Pilgrim, D. 2019. Key concepts in mental health. 5th ed. London, UK: Sage.

- Pinsof, W. M. 1988. The therapist client relationship: An integrative system perspective. Journal of Integrative Eclectic Psychotherapy 7:303–13.

- Pintrich, P. R., R. W. Marx, and R. A. Boyle. 1993. Beyond cold conceptual change: The role of motivational beliefs and classroom contextual factors in the process of conceptual change. Review of Educational Research 63 (2):167–99. doi:10.3102/00346543063002167.

- Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2016. Recommendations for creating better concept definitions in the organizational, behavioural and social sciences. Organizational Research Methods 19 (2):159–203. doi:10.1177/1094428115624965.

- Potter, J., and M. Wetherell. 1987. Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London, UK: Sage.

- PRISMA (2020). Flow diagrams for transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses available at http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- Ridner, S. H. 2003. Psychological distress: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 45 (5):536–45. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x.

- Risjord, M. 2009. Rethinking concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65 (3):684–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04903.x.

- Rodgers, B. L. 2000. Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques and applications 2nd, B. L. Rodgers and K. A. Knafl ed. 77–102. Cambridge, MA: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Rutter, D., J. Francis, E. Coren, and M. Fisher. 2010. SCIE systematic research reviews: Guidelines. London, UK: Social Care Institute for Excellence.

- SadatHoseini, A., H. Shareinia, S. Pashaeypoor, and M. Mohammadi. 2023. A cross-cultural concept analysis of healing in nursing: A hybrid model. BMC Nursing 22 (1):252. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01404-8.

- Sartori, G. 1984. Guidelines for concept analysis. In Social science concepts: A systematic analysis, ed. G. Sartori, 15–88. London, UK: Sage.

- Sartori, G. 2009. Part 1: Sartori on concepts and method. In Concepts and method in social science: The tradition of Giovanni Sartori, ed. D. Collier and J. Gerring, 11–178. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

- Schwartz-Barcott, D., and H. S. Kim. 2000. An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid Model of concept development. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques and Applications 2nd, B. L. Rodgers and K. A. Knafl ed. 129–60. Cambridge, MA: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Smith, S., and E. Mörelius. 2021. Principle-based concept analysis methodology using a phased approach with quality criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20:1–12. doi:10.1177/16094069211057995.

- Thompson, M. 2011. Ontological shift, or ontological drift? Reality claims, epistemological frameworks and theory generation within organisational studies. Academy of Management Review 36 (4):754–73. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.0070.

- UK Government (2022). Vulnerabilities: Applying all our health. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vulnerabilities-applying-all-our-health/vulnerabilities-applying-all-our-health#:~:text=Being%20vulnerable%20is%20defined%20as,risk%20of%20abuse%20or%20neglect.

- Vermes, C. (2018). Client factors associated with psychotherapeutic process and outcome: A concept analysis ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Manchester, UK.

- Walker, L. O., and K. C. Avant. 2010. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 5th ed. London, UK: Pearson Education.

- Wampold, B. E., and Z. Imel. 2015. The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. (2nd Ed.), Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

- Wuest, J. 1994. A feminist approach to concept analysis. Western Journal of Nursing Research 16 (5):577–86. doi:10.1177/019394599401600509.