ABSTRACT

This article reports on a study of mandatory assessment in mathematics for preschool-class children (aged six) and teachers’ opportunities to advocate Care for the learning of mathematics. Care for learners and Care for mathematics intersected in the teachers’ Grouping of students and their ability to Know the student. These play out as teachers promote availability and justice to students, and as teachers strive to make students’ knowledge visible, promote accuracy and gain legitimacy. It is concluded that teachers’ opportunities to advocate care for the learning of mathematics needs to be present also in the administration of assessment and to be put in the context of the school’s culture and student population, for teachers to be able to promote fair assessment for each student.

Care and ethics in and through assessment

The purpose of this study is to contribute to the understanding of how mandatory assessment in mathematics conditions preschool-class teachers’ Care for the learning of mathematics (CLM) and how the concept of care is conditioned. In the context of national assessment, fairness and equity are challenged by an enhanced focus on levels of achievement in mathematics, which generates ethical dilemmas for the teachers to handle in their teaching (Bagger, Citationin press; Ernest, Citation2019). The use of numerical data gives rise to a system imbued with all-encompassing and personalised assessment practices across education systems, whereby assessment is framed in a manner that attributes effort, ability, and outcomes to the individual, which is especially troublesome for students in need of support for their learning (Smith, Citation2016). It is a continuous challenge for teachers to keep up to date about students’ knowledge through, for example, national assessment, without simultaneously emphasising achievement as more important than learning, which can create stress among students (Högberg et al., Citation2020; Nygren, Citation2021). In the context of assessment, previous research internationally has repeatedly and identified a tension between care for the learning and the assessment of knowledge. Although often put aside in the discourse of assessment, care for learning and the learners has been shown to improve students’ measured performance, facilitate learning, and promote enjoyment of the subject of mathematics (Jansen & Bartell, Citation2013; Ransom, Citation2020; Watson, Citation2021).

Despite its ubiquity, care as a concept is elusive and not well defined or scrutinised in terms of its composition and implications for research and practice, especially not in relation to what mathematics and assessment are, and for whom it works. We claim that by acknowledging the implications of care through and in assessment in mathematics, researchers, policy makers and educators can better navigate assessment processes. This can help foster teaching and learning environments in which CLM is core. This study contributes knowledge on teachers’ opportunities to foster a caring approach towards mathematics learning during implementation of the mandatory assessment in mathematics at preschool-class level (six-year-olds) in Sweden. In addition, we elaborate on how CLM holds the potential to re-shape how the learner in need of support can be understood and approached; from the intention to understand their mathematics rather than in terms of the, quite common, deficit-oriented discourses (see Lewis, Citation2014; Nieminen et al., Citation2023).

Assessment, equity, and fairness – the case of early school years in Sweden

Despite national efforts to improve quality and equity in mathematics teaching in Sweden, there is still a downward trend in terms of demonstrable knowledge of mathematics, a gap in demonstrable knowledge between groups of students and an increasing proportion of students in need of support in mathematics (see Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2022). These trends emerge in the context of a lack of equity between groups of students, classes and schools, a difference that is already visible by the third school year. Hence, there is a risk that the pedagogical segregation shown in mathematics (Hansson, Citation2011) is reproduced and, in combination with the sometimes unequal sorting and labelling of students that assessment in mathematics can bring (Boistrup, Citation2017), that learning, development and assessment will be conditioned in a way that disadvantages some students.

The Swedish government have increased testing and grading in compulsory schooling with the rationale to improve outcomes, provide higher quality teaching, and increased equality (Ministry of Education, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In 2010, national testing became mandatory in school year three (9-year-olds). In 2011, this was followed by a further policy related to national assessment; namely, the introduction of grades in school year six (12-year-olds). In 2016, mandatory assessment was implemented for students in school year one (7-year-olds). The most recent change is the introduction in 2019 of mandatory national assessment in mathematics in preschool-class (6-year-olds), using material for evaluation called Find the Mathematics. This emphasises on assessment presents new challenges for individual teachers and teaching teams in preschool-class, and the school as an organisation, as this school year has its own curriculum, culture of teaching and child-oriented pedagogy. The rationale for introducing testing for preschool-class children is aligned with the Swedish government’s and school agencies’ focus on providing early support for students at risk of not meeting academic standards or those needing a greater degree of challenge, as part of their efforts to enhance educational equity and quality (Ministry of Education, Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

The assessment discourses in the preschool-class reflect its positioning between the norms and expectations of preschool and school, and so are shaped by the activity-focused teaching culture of pre-school (Vennberg, Citation2015, Citation2020). Furthermore, teachers in preschool-class have the possibility to impact students’ development in a positive way, due to their knowledge and ability to identify and assist students who require support in mathematics and to prevent a widening gap in progress. Teacher competence in supporting children’s mathematical development, subject knowledge and administering assessment in the subject are all key, therefore (Vennberg, Citation2015, Citation2020). Furthermore, assessment at the preschool-class level needs to be carried out in a way that is in line with its child-centred pedagogy and activity-based approach. The mimicking of the more traditional pedagogy of compulsory schooling is often referred to as the “schoolification” of early years education and has been highlighted in the aforementioned analyses of the assessment material used in preschool-classes and the political decisions and preparatory work related to these. The critique of schoolification has also been made by school authorities (Bagger, Citation2015). The impact of these assessments on students’ knowledge and equity is not yet known, as the initiative has not yet been evaluated (Swedish Schools Inspectorate, Citation2022). Both practitioners and critics, however, have reported challenges regarding equity in implementing these assessments (Bagger, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Bagger et al., Citation2019; Bagger & Vennberg, Citation2019, Citation2023). Earlier evaluations of the assessment material by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Citation2020) showed that although the assessments are carried out in accordance with instructions, in most schools the results are not evaluated and used to inform how students are supported or to develop teaching. This is also confirmed by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Citation2021), which states that teachers report a lack of time to complete the national assessment in preschool-class, and that special education professionals are not always involved. Hence, students most often excluded from taking part in the assessment are those with disabilities or who are new learners in the Swedish language. It seems, then, that rather than the assessment improving equity, quite the opposite may be happening.

Addressing the challenges with ethics and care in assessment

Ideas about the teaching of mathematics and how to assess learning are intertwined and, as both can have implications for equity and fairness, they should be addressed simultaneously. One way to do so is to explore assessment in mathematics from the perspective of a philosophy of mathematics education in which mathematics is understood as “fallible, changing, and like any other body of knowledge, the product of human inventiveness” (Ernest, Citation1991, p. xi). Conceiving of maths as a human and fallible intervention and invention, the active philosophy of mathematics education also includes ethical consideration of what it is to provide good mathematics education and assessment in the subject (Ernest, Citation1991). In the study at hand, we approach assessment in mathematics from the perspective of a philosophy of ethics of care in mathematics (Dubbs, Citation2020) and then draw on Noddings (Citation1988, Citation1992, Citation2013) work on layers of care in teaching, which covers everything from care of the self and to care for ideas, that build on and presuppose each other. Consequently, Noddings’ concept of the ethics of care is central to how we have approached the teachers’ understandings of their responsibility for mandatory assessment of six-year-olds in preschool-class. This is especially useful as teaching at this level is traditionally characterised by a pedagogy that foregrounds care and child-oriented teaching.

The philosophy of mathematics education and the theoretical ideas at work before, during and after the teachers’ implementation of mandatory assessment can help to explore how teachers make sense of the nature of mathematics, their assumptions about and epistemologies of learning – or, for what and for whom mathematics education is supposed to be a good – and also what it means to teach mathematics (Ernest, Citation1991). Consequently, the questions posed in the focus groups invited the teachers to express their ethics of care and ideas about the nature of mathematics and assessment, as well as to contest and negotiate the meanings of these. As depicted by Ernest (Citation2019), the first duty of care constitutive of ethical mathematics teaching is to care for the learner. A teacher’s personal philosophy of mathematics education will be central to whether and how CLM can take precedence during assessment (Ernest, Citation1991; Watson, Citation2021). As Ernest (Citation2019) has pointed out, the ethics of the mathematics teacher is enacted through their professional practice and towards those in their care. Hence, the teacher’s ethical agency is of utmost importance and will impact how the curriculum is delivered and can be received by a diversity of learners. It is important to recognise that a teacher’s ideas on the nature of mathematics assessment, and their philosophy and ethics of mathematics education, will vary depending on national contexts and the culture, history and social and political values that pervade the education system overall.

Care for the learning of mathematics

The following provides a review of how CLM has been researched and what is already known. As shown by Archer (Citation2017) in the English education system, which has some similarities to Sweden, the assessment policy in the reception year of school (4–5 years old) might not include an ethics of care; teachers’ reported experiences suggest that this is therefore rather put in the background. Despite this lack of ethics of care, assessment often includes social dimensions and perceptions that need to be accounted for and handled (Black & Wiliam, Citation2010). Such aspects can negatively affect students’ self-image and self-confidence, which can contribute to deteriorating progress in the subject of mathematics (Marks, Citation2011; Middleton & Spanias, Citation1999; Putwain et al., Citation2012; Räty et al., Citation2004; Reay & Wiliam, Citation1999). Furthermore, social dimensions of assessment practices, as well as justice and equity, are put to the test in situations where assessment has or is perceived to have a sorting function. Questions about for whom the teaching works and who can thereby achieve success in learning are, therefore, core (Au, Citation2008; Peters & Oliver, Citation2009). Hence, attention must be paid to CLM, for each and every student, during assessment.

Within the field of mathematics education, care has often been studied in relation to students in need of support, though not exclusively. This research often draws from Noddings’ concept of the ethics of care (Citation1988, Citation1992, Citation2013). Researchers such as Watson (Citation2021), Jones and Lake (Citation2020), Long (Citation2011), and Nicol et al. (Citation2010) have explored care in relation to ethical aspects of mathematics education. There is criticism, however, that some research does not sufficiently consider social, cultural, and political power structures in society (Hunter & Stinson, Citation2019; Maloney & Matthews, Citation2020; Matthews, Citation2020; Ransom, Citation2020). The theoretical framework of the current project addresses the need to examine different norms and cultural and socioeconomic conditions through CLM (Watson, Citation2021), where the surrounding cultural and educational contexts are seen as crucial to what happens in the classroom.

Care is often portrayed as a choice teachers make to establish good relationships with their students. This goes beyond building social or safety-oriented relationships and involves supporting students academically while caring for their individuality (Bartell, Citation2011; Ransom, Citation2020). A good relationship becomes essential for the student to be able to receive this care (Long, Citation2011). In this sense, care can be understood as a didactic choice made by the teacher to support students’ learning through teaching that respects their abilities and individuality. These choices are manifested through actions in the classroom, sometimes referred to as caring. In the academic and content-focused nature of these choices, care is used to emphasise teachers’ conscious decisions to acknowledge students’ mathematical ideas (Long, Citation2011).

Hackenberg (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) is a key reference in this context as she has extended Noddings’ ethics of care to incorporate aspects of the pedagogical relationship that serves to bring together affective and cognitive aspects of mathematics learning. Hackenberg (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) describes this as the teacher needing to be able to undergo cognitive decentring to set aside their own mathematical understanding and concepts when exploring mathematics systems and operations with the student. Furthermore, Jansen and Bartell (Citation2013) have built upon Hackenberg’s work and explored mathematics education by distinguishing between social and interpersonal care and academic care, which is more frequently manifested in teaching. These authors share the belief that care involves respecting and welcoming a range of students in mathematics learning and having high expectations.

Care goes beyond the relationship between the student and teacher and the distinction between academic and social aspects. Researchers have shown that care in mathematics education is influenced by and based on the development of a community in mathematics learning, and it is essential to recognise the larger societal context in which this community develops. Care extends beyond individual relationships, therefore, as it involves respecting and being aware of the societal context, families’ lives, and the school’s approach to diversity (e.g. Ahn et al., Citation2015; Averill, Citation2012; Ellerbrock & Vomvoridi-Ivanovic, Citation2022; Hunter & Stinson, Citation2019). Students cannot leave parts of themselves outside the classroom and, therefore, teaching must address the whole student with both understanding and high expectations (Simic-Muller, Citation2018). Research has shown that early and more extensive assessment can lead to stress and shift the focus from learning to achievement. Unequal learning conditions have a growing impact, and the focus of learning has become increasingly instrumental (Högberg et al., Citation2020; Nygren, Citation2021). It is therefore crucial to understand the prerequisites for teachers to be able to enact CLM before, during and after assessment.

Theoretical underpinnings

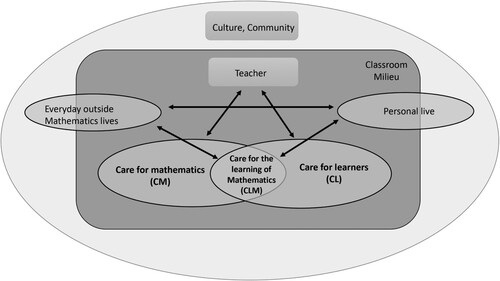

The study at hand connects the ethics of care to theories of mathematics education and sociology by advocating Watson’s (Citation2021) model of CLM in the structuring and analysis of data, in the presentation and discussion of results and in the overall approach to the assessment of mathematics. In their book, Care in Mathematics Education, Watson (Citation2021) has explored care of, for, and through mathematics teaching and refers to “care for mathematics in its fullest sense; care for students including knowledge of community; and these two are connected by care for their learning of mathematics” (p. 91). Watson shows that Care for the learners (CL) and Care for mathematics (CM) are intertwined and interdependent. They overlap in CLM, as displayed in .

Figure 1. A visualisation of CLM, adapted from Watson’s (Citation2021) elaborated didactical triangle.

Watson’s (Citation2021) elaborated didactic triangle shows “sources of influence on the teacher’s care for the learning of mathematics” (p. 197) and recognises that the learning environment is not only the content, materials, and strategies applied in the classroom and the classroom milieu, but also includes the community and family context. Relational and emotional aspects are also included in the CL, alongside cognitive care (care for and knowledge of students’ ways of working and their cognitive prerequisites). Cognitive care implies that it is important to promote exploration and an active mind, and to allow students to be challenged and to explore and learn ideas, generalities, and patterns. All of which may in turn develop critical intellect and personal autonomy. Watson demonstrates how teachers, through their didactic choices and teaching, play a central role in this respect. If teachers fail to embrace students’ cognitive needs and ways of functioning in their teaching, cognitive bullying may occur, which significantly hampers learning. Hence, the care framework derives from the standpoint that both mathematical challenge and sensitivity to students is needed to stimulate learning (Jaworski, Citation1996; Potari & Jaworski, Citation2002). Watson has furthered the understanding of the interrelatedness of mathematical challenge and sensitivity to students by exploring and defining the intersection of CL and CM as CLM.

In this study, assessment in preschool-class is understood as having the potential to be a shared endeavour and responsibility between students and teachers, in what Watson refers to as a mathematics education being a field of possibilities that includes both high quality instruction as well as inquiry. We claim that this dichotomy between inquiry and instruction built into mathematics education affects students’ opportunities to learn (see Moss et al., Citation2008), particularly in the context of assessment and in terms of the students’ opportunities to display knowledge (ODK) (see Bagger, Citation2022; Citationin press). We therefore draw on a combination of the field of possibilities built into mathematics education (Watson, Citation2021) and students’ ODK in our understanding of assessment in mathematics. Hence, we explore teachers’ opportunities to exercise CLM and how that relates to students’ ODK as taking place in a field of opportunities, which means that care is examined as a didactic action and a choice in some sense. This also means that teachers’ high expectations and their ability to tailor teaching to students’ cognitive and personal conditions are central, as this is considered a prerequisite for exercising CL, according to Watson’s (Citation2021) model. Furthermore, the study raises questions about how the classroom milieu, the school’s teaching culture and community, and societal context relate to teachers’ opportunities to demonstrate CLM and how it is conditioned in the context of educational practice and mandatory assessment.

Research design and methods for collecting data

The data collection was undertaken through focus group conversations at two schools as teachers planned for, executed, and evaluated the assessment during the implementation period in 2018 and 2019. The participating schools had contrasting profiles regarding their student population. Hillcrest School’s student population is diverse in terms of language, culture, and socio-economic status. In contrast, Pinewell School has a more homogenous group regarding language, culture, and socio-economic status, and is situated in a middle-class area. The rationale for this selection is the understanding that there are disadvantages in the learning of mathematics that correlate to students’ language, culture, and socio-economic status. This might also affect teachers’ opportunities to advocate CLM. Each focus group consisted of four preschool-class teachers from each school. The focus groups took place on three separate occasions: as the teachers familiarised themselves with the assessment material; during the period of implementing the assessment with the students; and subsequently after the assessments when they reflected on their experiences and the outcomes of the assessment. During these sessions, each of which took between 1 h and 1 ½ hours, prompts were available to support reflection on the idea of mathematics and assessment and aspects of equity and fairness. In the first focus group, the assessment instructions and material itself was on the table. During the second, the same instructions and material together with teachers’ notes on how things had gone so far were available. During the last session, the teachers’ documentation of the outcome of the assessment was available. The focus groups reflected upon the nature of mathematics, the assessment itself and the students’ needs and opportunities to display knowledge and engage in the assessment. The researcher’s role was to stimulate reflection by posing questions on the material and on teachers’ experiences, reflections, and routines, and to provide input from earlier research or national reports on mandatory assessment in mathematics with younger students. Following each focus group the material gathered was transcribed.

The research context: preschool-class and striving to find the mathematics

Preschool-class in Sweden is a mandatory year of education that follows preschool and precedes the nine years of compulsory schooling. Students enter preschool-class at six years old. This will become compulsory from 2026, which means that there will then be 10 years of compulsory schooling (Ministry of Education, Citation2021). The main objective of the preschool-class assessment, Find the Mathematics, is to influence teachers’ understanding, teaching practices, and students’ learning outcomes and is part of an initiative to ensure the necessary support for students not meeting standards or needing a greater level of challenge though high-quality teaching (Swedish Government, Citation2017). In 2018/2019, the assessment was voluntary for preschool-classes. The assessment was composed of four activities and students were to be seated in small groups and to collaborate on some aspects. For each activity, teachers were given instructions on its purpose, how to perform the assessment and what items it should contain. How to group students, and what support or adaptions individual students would be given, was up to the teachers to decide. Teachers had to develop some of the materials themselves, so that it was appropriate to their students.

The four activities correspond to knowledge and skills recognised as being important for positive development in mathematics, with the overall purpose to evaluate whether students display interest in the subject and how they manage certain mathematical skills. The four activities and their respective purpose were as follows:

Playground: An activity in which students were presented with a map of a playground and a figure that they were supposed to place in certain ways. The teacher asks the group of students to navigate and solve a task together. The activity displays their knowledge of spatiality, time, and space.

Patterns: This requires students to repeat and construct a pattern that the teacher shows them. The students work individually but are seated in a group. This activity is about identifying, repeating, and constructing a pattern.

Sand/rice: This activity is focused on measuring and assesses the ability to ‘communicate and reason on the principles of measuring’. Hence, students are to solve problems given by the teachers together. The activity Sand/rice could be carried out in snow as an alternative, and different containers could be used.

Dices: The activity with dices is designed to see whether students can communicate and recognise figure numbers, connect them to symbols and know the basic principles of counting. Students are seated in a group, but each gets to throw the dices and take an active role. They are also asked questions as part of the activity.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations have been made throughout the research process and in accordance with the Swedish Research Council guidelines (Citation2017) and the four main requirements related to humanities and social sciences research: the information requirement, the consent requirement, the confidentiality requirement, and utilisation (Swedish Research Council, Citation2002). Research ethics is enacted, first and foremost, through the choice of topic and all students’ equal rights to demonstrate knowledge during assessment in mathematics. The researchers worked reflexively throughout the process of designing the project, collecting, and analysing the data. This includes a careful and systematic approach to coding and thematising to ensure accurate representation of what was expressed during the focus groups. All participants gave active consent after being informed of the purpose of the project and what participation entailed, how data and personal information would be collected and stored and who would have access to it. Furthermore, they were informed that participation is voluntary, and that withdrawal is possible at any time and with no explanation. No individual teachers or schools can be identified in the transcripts or written reports. As the focus group reflections focused on the assessment material and the process of administering this, no information on individual students was collected and therefore the consent of students and their guardians was not required. They were, however, informed that their teachers took part in this project.

Exploring care for the learning of mathematics

The transcriptions of the focus groups were scrutinised by adopting Watson’s (Citation2021) model of CLM. Hence, the teachers’ ethics of care and philosophy of mathematics was brought to the fore as were their opportunities to enact CLM and thereby to support students to engage in the joint field of opportunities, which includes high quality instruction as well as inquiry (also see Watson, Citation2021). The teachers were not asked about CLM explicitly, but instances of it were identified and analysed in the body of data and form part of the composed narratives that displays teachers’ ethics of care and philosophy of mathematics.

As demonstrated, CLM is generated at the intersection between CM and CL in Watson’s model (see ). What teachers say about the mandatory assessment material provides narratives on whether and how they think students can make sense of the assessment and the mathematical content and also how students can be given equal access to engage in the field of opportunities in mathematics learning. Furthermore, the analytical interest in these narratives lies in exploring the opportunities teachers have to demonstrate CLM in the context of mandatory assessment and with a special focus on students in need of support for their learning. Hence, the analysis seeks to identify what is required from the teachers, the school, and the assessment material to support students’ learning in mathematics and to enable teachers to care for the learning of mathematics. This was analysed through the lens of Watson’s model of CLM. Consequently, elements relating to CM and CL were identified from the transcripts and analysed to identify themes. These two aspects were then further explored regarding differences, tensions and patterns between the schools and themes. Hence, CLM was unravelled in the specific context of mandatory assessment in the preschool-class during the implementation period.

Analytical procedure

A systematic qualitative content analysis was conducted in three procedural steps inspired by Feucht and Bendixen (Citation2010): summary, explication, and structuring. Transcripts were read and audio files listened to multiple times in the process of analysis and interpretation. The reliability of the interpretation was secured throughout the process by one researcher selecting, coding and thematising transcripts from one school first, then swapping schools and comparing the coding and selections made. Any inconsistencies in applying core concepts and coding were then adjusted. Finally, a joint reading and interpretation of all selections, codes and themes was undertaken by putting the two schools and themes alongside each other.

The first stage in the analytical process, summary, reduced the material and involved selecting relevant text and organising the content according to whether passages related to CM or CL. We identified these by applying Watson’s (Citation2021) conceptualisations. Hence, CM was identified in and selected from the transcripts whenever teachers talked about and expressed concerns regarding how the mathematical content was, could be or should be represented or understood. CL was identified whenever teachers talked about and expressed concerns regarding how the learner was, could be or should be represented or understood. These were coloured in turquoise and yellow and copied and pasted from the transcripts into a separate analytical document. Importantly, the selected parts often consisted of reflections that co-existed or/and followed on from or preceded each other but were never constituted by the same segments of texts. This indicates that the two concepts were in fact very closely aligned but, at the same time, distinct from each other. In this first step of selection, the teachers’ reflections were also summarised by paraphrasing them in terms of their meaning.

In the second analytical process, explication, we further explored and refined these content-bearing segments of the teachers’ reflections by providing explanatory descriptions of their central aspects. This step involved the identification of overarching codes through an iterative process and with explanations closely aligned with the empirical data. The descriptions could, for example, pertain to how students were described, emphasise the importance of certain knowledge, or the obstacles and opportunities to demonstrate knowledge, such as language, academic level, or the school environment.

In the third step, structuring, codes were defined, ordered, and reduced to overarching themes that incorporated related codes. This was helpful as it made it possible to keep the variations between schools and within similar phenomena. Consequently, we coded and categorised the selected texts, and assigned content-related headings such as accessibility, support, fairness, language, organisation, and so on. Finally, we systematically explored the potential connections between schools and themes. This involved explicitly highlighting differences, similarities, and overlaps between CM and CL in the emerging themes and at the two schools. Finally, we discussed the intersection between CM and CL and the teachers’ prerequisites that enable them to sustain CLM.

Care for the learning of mathematics during assessment

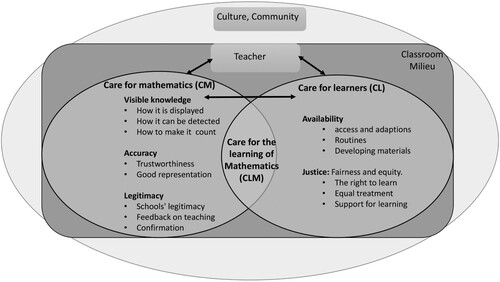

In the following, we discuss the possibilities identified for teachers to promote CLM during assessment. Identified themes are presented and reflected upon with a focus on similarities and differences between the themes and the two schools regarding CM and CL in the context of assessment. Themes identified in connection with CM were: visible knowledge, accuracy, and legitimacy. For CL, availability and justice emerged as themes. The results are presented as narratives that explore tensions, overlaps, and differences between themes and schools. The themes are exemplified by representative quotes from the teams of teachers.

Care for mathematics

Here, the themes identified regarding CM will be presented through a narrative. Three themes were identified at both schools: visible knowledge, accuracy, and legitimacy. These have in common that their primary objective is mathematics and mathematical knowledge.

Within the theme visible knowledge, three sub-themes emerged: how knowledge is displayed by students; how the knowledge made visible can be detected by the teacher; and how to make visible knowledge count during the assessment at hand. The teams of teachers at both Hillcrest and Pinewell stress the importance of identifying the visible knowledge in what the students display. At Pinewell School, students’ display of knowledge is talked about in terms of the student being knowledgeable in mathematics and as evaluating correctness in knowledge: I know she can do it, roughly. Well, but she didn't do it correctly during this assessment, so then it is accounted for as she can't. Teachers at Pinewell School also position the material as a way for them to detect strong or weak students, in order to adapt future teaching, for example by seeking support from the special education teacher:

The special education teacher has been a support beforehand - we have discussed students and how to carry through the assessment - is available after the moment and will evaluate the results. Also, afterwards she can support our teaching if needed.

Many children who have another mother tongue and are not yet fluent in Swedish have been very good (in mathematics) in their language. If you (the teacher) don't see it during this assessment, you cannot record it.

Furthermore, how the visible knowledge is detected by teachers varies between schools. At Pinewell School students’ social and verbal skills matter when determining whether a student’s knowledge is weak or strong. Here, students showing an interest is also challenging for teachers to use as an indicator of knowledge: This does not show that they have understood what a pattern is. It just shows that they can do the same and imitate. Instead, this team of teachers refers to communicating verbally as being equivalent to reasoning and knowing. At both schools, how quickly the students respond is also seen as an indication of how to value or understand students’ knowledge: … we have children who are very quick to respond. So, some will never get it, but repeat what the person who answered first says then. It was also a challenge for teachers to understand whose knowledge is on display when the assessment activities are undertaken in group settings. At Hillcrest School, this was also referred to as lacking language and therefore being less able to interact. At Pinewell School, the systematisation and documentation of the outcome of activities were regarded as providing a visualisation of students’ correct knowledge, and the assessment material is considered reliable. At Hillcrest School, the reliability was rather put into question by the team of teachers (also see theme accuracy). The items and instructions in the material needed to be worked around and considerable time was spent on doing so: … four different vessels that hold … well, about one decilitre, two decilitres, five decilitres and one litre. And there should be no grading on the vessels. Notably, the teachers did not have the support of special education professionals before or during the assessment and felt rather left on their own to manage adaptations and make the material work for their students. At times they expressed that they lacked knowledge of the language needed to do the student justice:

There is no equity, since our students do not get to have mother tongue language education. And we do not have access to the special education teacher either during or before the assessment.

The theme legitimacy was also displayed differently in the two schools. At Pinewell School legitimacy was linked to the actual assessment and whether the knowledge shown was seen as a reliable display of knowledge. Hence, teachers could use the outcome to confirm students’ previous display of knowledge in other situations and teaching. At Hillcrest School legitimacy was connected to teachers becoming more confident in teaching due to the feedback given, on the contribution their teaching had made, and also in making arguments for receiving more support from the health care team for specific students as they now had evidence of students not meeting expectations.

Care for learners

Two themes that concerned CL – Availability and Justice – were identified in the analysis at both schools, although with very different foundations and rationales. Both themes were connected to support in different ways. Availability referred more to developing materials, routines surrounding the assessment and making mathematics accessible through support. Justice concerned support in terms of the right to learn, equal treatment and learning being enabled through support.

At Hillcrest School availability centred on what makes the activity or task accessible to the student and whether the content is known or unknown. Accessibility was presented as the prime concern in terms of how to make it possible for students to understand the activity and how the teachers could translate or simplify the activity so that the student was enabled to access the content: “ … it must be a well-known material for the students, which demands that we have used it for a while already before the assessment”.

At Pinewell, availability was mostly connected to students feeling trust towards and having a good relationship with the teacher and to the assessment situation. This would help them to feel relaxed and safe and thereby create the best opportunities for the student to display knowledge:

It is important that they know us well, since it is a constrained situation. That the one they do it with, has a good relation to them. That they have confidence in us and can engage, and that it feels relaxed.

The theme justice was also found at both schools and is connected to the support theme but is focused on fairness and equity. This is shown in statements that express that there is a risk that a lack of proficiency in the Swedish language is considered to be interpreted as weak knowledge in mathematics, which can lead to low expectations of students’ performances. At Pinewell School the theme of justice arose in relation to support being granted and being effective, and how the school health care team was involved in this. This aspect of the theme also related to giving students the best opportunity to display their knowledge fairly: … the children could be given a second chance. She must have had a bad day or something. You felt that it was not fair. We knew she could do more.

At Hillcrest School, support was talked about as complex and in relation to teachers’ opportunities to provide support. At an organisational level the lack of resource to be able to meet the needs of students requiring support was mentioned: … then also the problem there, it's that even the interpreters don't really understand. At a classroom level they talked about how to create a learning environment that would help students to participate, have interest and curiosity and express themselves, as this is seen as a way to identify students’ knowledge. In the classroom, teachers know all of their students and know how to best match the students when doing group activities to ensure they are supported. At an individual level the previous knowledge that students bring to school matters in how the teachers understand the students’ needs and to bridge the gap in students’ unequal conditions.

Assessment as a field of opportunities and tensions

The themes concerning CM – visible knowledge, accuracy, and legitimacy – intersect with aspects of CL – availability and justice, especially in relation to two aspects that the teachers refer to: in reflections on the grouping of students and reflections on the importance of knowing the student. Importantly, this intersection is not always one of harmony. Instead, there are frictions and tensions as the way these themes are expressed aims towards different targets. Hence, what we understand as a field of opportunities and tensions regarding Assessment as CLM, emerges in the elements constituting the intersection of CL and CM. This is illustrated in and is thereafter elaborated on in more detail.

Figure 2. Aspects of CLM during assessment placed in Watson’s (Citation2021) elaborated didactical triangle, adapted by authors.

Grouping of students was expressed in terms of students’ need to be grouped in a way that increased their opportunity to display knowledge. The grouping of students was considered important as the groups are the fora in which the students need to understand, communicate, and interact to display their interest in and knowledge of mathematics. Hence, both CM and how to make it as present as possible as well as CL in terms of social relations, level of knowledge, personality, language, and patterns of communication came together in the consideration of grouping students.

Challenges and opportunities referred to regarding the grouping of students varied between the schools and some foundational differences were expressed. For Hillcrest School, grouping was connected to increasing interaction between students. This would offer the students time to think, which is connected to styles of interaction that are important to working well together. For example, students who are very talkative would not be paired with those who are more silent. Also, language is important: there needs to be time to listen and time to think, and space to express these thoughts. This space to express thoughts is also connected to students feeling safe with each other and having the social foundations, e.g. personality and language, to interact. At Pinewell school the grouping of students was instead focused on maximising students’ achievement. Here, too, the teachers emphasised the importance of feeling safe, but that safety instead stems from being relaxed and having the stamina to listen to each other, and refers also to social safety, being with peers you know and not feeling stressed out. Smaller groups are not seen to always be the most appropriate arrangement as some students might feel exposed and tested in a smaller group, while for others a small group would be an ideal adaptation to their learning needs.

To know the student was talked about in terms of providing the students with fair opportunities to display their mathematical knowledge. Teachers at both schools expressed that they needed to know both the present state of the student as well as their interests, personality, and knowledge more generally. Hence, CL was expressed quite clearly but CM is highly intertwined with knowing the student well as this in itself has the purpose of putting mathematics to the fore. Not knowing the student well enough could add to their stress. This intersection consists of a genuine CL in terms of justice and well-being and the simultaneous insight that the student will struggle to make their mathematical knowledge visible if they are too stressed. One way to diminish stress was to secure access to the material. This was mentioned as key at both schools but for different students and different reasons. Access had different foundations in the two schools. At Hillcrest access was referred to in terms of students’ familiarity with the material for the students and with new ways of working. At Pinewell, this familiarity with the material was talked about in relation to a student with a specific diagnosis, and whose motivation to engage with the material could be hindered by explicit talk about having to do this at all. At Pinewell School, stress was referred to as an issue for the teachers to handle and in terms of teachers’ responsibility to provide fair assessment. At Hillcrest, stress was instead attributed to students. In both cases, the student should be enabled to display their knowledge to the fullest and fairly. The teachers at both schools also expressed that they really know the students’ levels, and in the case of someone underperforming they chose to give them a further opportunity to retake the assessment. At the same time, however, they were not certain that this practice was in accordance with instructions.

Final reflections and implications

When applying the framework for teachers’ CLM in the context of assessment, tensions and connections appear between CM and CL. Teachers’ reflections on the assessment at both schools framed it as a kind of balancing act: to be kind and to be fair, to be insightful into students’ personal situations but to not be biased by them, not to support too much or too little and so forth. Klemp’s (Citation2020) environment building approaches enable students to explore and challenge their understandings. The environment plays a significant part in the experience of assessment. The teachers reflected that, as assessment materials are externally set and where these do not align with students’ experiences, it might hinder the visualisation of knowledge. This, in turn, connects the assessment material to issues of equity and fairness. Students receive feedback not only from teachers and peers but also from the assessment itself. Rønsen (Citation2013) has shown how the didactics of feedback impact students’ understanding of themselves and the knowledge itself and affect how they can make sense of the situation.

The teachers’ narratives on whether and how students can make sense of the situation and feedback can be understood with support of Watson’s (Citation2021) model. This can also highlight how the students’ wider milieu in terms of family and community is important in the CL. Teachers at Hillcrest School refer to language as a resource but also, due to the design of the assessment material, as something that differentiates students. Students who are not able to communicate and display their knowledge and interest will be the objects of cognitive bullying and a lack of cognitive care at a system level, due to the assessment material (Watson, Citation2021). Here the teachers express that they would prefer to learn together with their students but feel the pressure to instead assume control of the knowledge. Regarding knowledge, and CM and CL, this represents a tension. In some cases, CL would mean to focus on what it is to learn, challenge and explore rather than on evaluating knowledge. Teachers indicate that caring about students entails expecting things from them. Similarly, Watson (Citation2021) discusses care in terms of having high expectations of students. Teachers here express care for the students’ previous experiences and their wider milieu, as depicted in Watson’s framework.

The findings show discrepancies in teachers’ ideas on students as test-takers and the meaning assigned to mathematical knowledge and assessment. Such tensions may lead to pedagogical dilemmas for preschool-class teachers during the assessment (Bagger, Citationin press). Earlier research also indicates that teachers in Sweden struggle to balance the testing discourse and the caring approach during assessments with young students (Bagger, Citation2015). These ethical dilemmas further complicate CL during assessment and might impact the teacher-student dynamic and overall learning environment.

The results from this study can support teachers’ opportunities to understand, develop and adapt ethical national assessment practices and to advocate CLM. CLM in this context demands an awareness and a balancing of the elements that constitute both assessment and care, in order for assessment to support CLM: to make knowledge visible with accuracy to gain legitimacy in teaching, but at the same scale this towards availability and justice in the assessment situation. To pay attention to these elements seems to be key to enabling all students to demonstrate their knowledge in a fair way. There is a need to continuously redefine and develop care for learning, both in research and practice. The study displays similarities but also differences between the two schools, with some structural disadvantages being present, although teachers are doing their very best to make sure the assessment is fair and supportive for each student. To achieve this, questions need to be posed to contextualise the milieu at hand. CLM holds the potential to help to reform assessment into a shared endeavour and responsibility, and as taking place in a field of opportunities that includes both high quality instruction and, at the same time, inquiry (also see Watson, Citation2021). This can stimulate learning and support students’ opportunities to display knowledge (ODK) simultaneously, rather than focusing only on one of these.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahn, R., Catbagan, P., Tamayo, K., Yeong I, J., Lopez, M., & Walker, P. (2015). Successful minority pedagogy in mathematics: US and Japanese case studies. Teachers and Teaching, 21(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.928125

- Archer, N. (2017). Where is the ethic of care in early childhood summative assessment? Global Studies of Childhood, 7(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610617747983

- Au, W. W. (2008). Devising inequality: A Bernsteinian analysis of high-stakes testing and social reproduction in education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(6), 639–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690802423312

- Averill, R. (2012). Caring teaching practices in multiethnic mathematics classrooms: Attending to health and well-being. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 24(2), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-011-0028-x

- Bagger, A. (2015). Prövningen av en skola för alla: nationella provet i matematik i det tredje skolåret. [Doctoral dissertation, Department of Mathematics and Science Education]. Umeå University.

- Bagger, A. (2021a, November 4-5). Access to displaying knowledge during assessment: A matter of sustainability [Paper presentation]. NORSMA10, Reykjavik, Iceland. (Online Conference).

- Bagger, A. (2021b, September 6-10). Evaluation of Swedish educational material [Paper presentation]. European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Geneva, Switzerland, (Online Conference).

- Bagger, A. (2022). Opportunities to display knowledge during national assessment in mathematics: A matter of access and participation, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(1), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1853970

- Bagger, A. (in press). Ethical dilemmas and professional judgement during national assessment in mathematics. In P. Ernest (Ed.), Ethics and mathematics education: The good, the bad and the ugly (pp. x–x). Springer.

- Bagger, A., & Vennberg, H. (2019, August 19–20). Early assessment in mathematics, the ethics in a practice close research approach [Paper presentation]. Fjärde nationella konferensen i pedagogiskt arbete, Umeå.

- Bagger, A., & Vennberg, H. (2023, March 15-17). The fabrication of SEM-students as knowers in mathematics - through mandatory assessment in preschool-class. [Paper presentation]. NERA, Oslo, Norway.

- Bagger, A., Vennberg, H. & Björklund, L. B. (2019). The politics of early assessment in mathematics education. Proceedings of the Eleventh Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education. https://hal.science/hal-02421225

- Bartell, T. G. (2011). Caring, race, culture and power: A research synthesis toward supporting mathematics teachers in caring with awareness. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 4(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/10.21423/jume-v4i1a128

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200119

- Boistrup, L. B. (2017). Assessment in mathematics education: A gatekeeping dispositive. In H. Straehler-Pohl, N. Bohlmann & A. Pais (Eds.), The disorder of mathematics education. Challenging the sociopolitical dimensions of research (pp. 209–230). Springer.

- Dubbs, C. (2020). Whose ethics? Toward clarifying ethics in mathematics education research. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 54(3), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12427

- Ellerbrock, C. R., & Vomvoridi-Ivanovic, E. (2022). Setting the stage for responsive middle level mathematics teaching: Establishing an adolescent-centered community of care. Middle School Journal, 52(2), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219778

- Ernest, P. (1991). The philosophy of mathematics education. Falmer Press.

- Ernest, P. (2019). The ethical obligations of the mathematics teacher. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 3(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2019.6

- Feucht, F. C., & Bendixen, L. D. (2010). Exploring similarities and differences in personal epistemologies of U.S. and German elementary school teachers. Cognition and Instruction, 28(1), 39–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370000903430558

- Hackenberg, A. (2010a). Mathematical caring relations: A challenging case. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 22(3), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219778

- Hackenberg, A. (2010b). Mathematical caring relations in action. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 41(3), 236–273. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.41.3.0236

- Hansson, Å. (2011). Ansvar för matematiklärande. Effekter av undervisningsansvar i det flerspråkiga klassrummet. [Doctoral dissertation, Institutionen för didaktik och pedagogisk profession]. Göteborgs Universitet.

- Högberg, B., Strandh, M., & Hagquist, C. (2020). Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years – the role of school-related stress. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112890

- Hunter, J. G., & Stinson, D. W. (2019). A mathematics classroom of caring among a black male teacher and black male students. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 21(1–2), 21–34.

- Jansen, A., & Bartell, T. (2013). Caring mathematics instruction - middle school students’ and teacher’s perspectives. Middle Grade Research Journal, 8(1), 33–49.

- Jaworski, B. (1996). Investigating mathematics teaching: A constructivist enquiry. Taylor & Francis.

- Jones, I., & Lake, V. E. (2020). Ethics of care in teaching and teacher-child interactions. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 55(2), 51–65.

- Klemp, T. (2020). Early mathematics – Teacher communication supporting the pupil’s agency. Education, 48(7), 833–846. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1663893

- Lewis, K. E. (2014). Difference not deficit: Reconceptualizing mathematical learning disabilities. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 45(3), 351–396. https://doi-org.db.ub.oru.se/10.5951/jresematheduc.45.3.0351

- Long, J. S. (2011). Labelling angels: Care, indifference and mathematical symbols. For the Learning of Mathematics, 31(3), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/41319600

- Maloney, T., & Matthews, J. S. (2020). Teacher care and students’ sense of connectedness in the urban mathematics classroom. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 51(4), 399–432. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc-2020-0044

- Marks, R. (2011). ‘Ability’ in primary mathematics education: Patterns and implications. Research in Mathematics Education, 13(3), 305–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794802.2011.624753

- Matthews, J. S. (2020). Formative learning experiences of urban mathematics teachers’ and their role in classroom care practices and student belonging. Urban Education, 55(4), 507–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919842625

- Middleton, J. A., & Spanias, P. A. (1999). Motivation for achievement in mathematics: Findings, generalizations, and criticisms of the research. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30(1), 65–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/749630

- Ministry of Education. (2017a). Uppdrag att ta fram kartläggningsmaterial och revidera obligatoriska bedömningsstöd och nationella prov i grundskolan, sameskolan och specialskolan. (Governmental decision and assignment to produce mapping material and revise mandatory assessment support and national tests in primary school, Sami school and special school). Regeringsbeslut, Regeringen, Utbildningsdepartementet. U2017/02561/S.

- Ministry of Education. (2017b). Uppdrag att genomföra kompetensutvecklings- och implementeringsinsatser avseende en garanti för tidiga stödinsatser i förskoleklassen, grundskolan, specialskolan och sameskolan. (Governmental decision and assignment to carry out competence development and implementation efforts regarding a guarantee for early support initiatives in the pre-school class, primary school, special school and Sami school). Regeringsbeslut, Regeringen, Utbildningsdepartementet. U2018/02959/S.

- Ministry of Education. (2021). En tioårig grundskola – Införandet av en ny årskurs 1 i grundskolan, grundsärskolan, specialskolan och sameskola, (Governmental Investigation to implement 10 yearlong compulsory school(, SOU 2021:33.

- Moss, A. P., Pullin, D. C., Gee, J. P., Haertel, H. E., & Young, L. J. (2008). Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn. Cambridge University Press.

- Nicol, C., Novakowski, J., Ghaleb, F., & Beairsto, S. (2010). Interweaving pedagogies of care and inquiry: Tensions, dilemmas and possibilities. Studying Teacher Education, 6(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2010.518494

- Nieminen, J., Bagger, A., & Allan, J. (2023). Discourses of risk and hope in research on mathematical learning difficulties. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 112(2), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-022-10204-x

- Noddings, N. (1988). An ethic of caring and its implications for instructional arrangements. American Journal of Education, 96(2), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1086/443894

- Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. Teachers College Press.

- Noddings, N. (2013). Caring a relational approach to ethics & moral education (2nd ed., updated.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520957343

- Nygren, G. (2021). Jag vill ha bra betyg: En etnologisk studie om höga skolresultat och högstadieelevers praktiker. [Doctoral dissertation]. Uppsala University.

- Peters, S., & Oliver, L. A. (2009). Achieving quality and equity through inclusive education in an era of high- stakes testing. Prospects: Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 39(3), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-009-9116-z

- Potari, D., & Jaworski, B. (2002). Tackling complexity in mathematics teaching development: Using the teaching triad as a tool for reflection and analysis. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 5(4), 351–380. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021214604230

- Putwain, D. W., Connors, L., Woods, K., & Nicholson, L. J. (2012). Stress and anxiety surrounding forthcoming standard assessment tests in English schoolchildren. Pastoral Care in Education, 30(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2012.688063

- Ransom, J. C. (2020). Love, trust, and camaraderie: Teachers’ perspectives of care in an urban high school. Education and Urban Society, 52(6), 904–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124519894973

- Räty, H., Kasanen, K., Kiiskinen, J., Nykky, M., & Atjonen, P. (2004). Children’s notions of the malleability of their academic ability in the mother tongue and mathematics. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 48(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383042000245807

- Reay, D., & Wiliam, D. (1999). “I’ll be a nothing”: Structure, agency and the construction of identity through assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 25(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250305

- Rønsen, A. K. (2013). What teachers say and what students perceive – Interpretations of feedback in teacher-student assessment dialogues. Education Inquiry, 4(3), 22625. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i3.2262

- Simic-Muller, K. (2018) Motherhood and teaching: Radical care. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 8(2) 188–198. https://doi.org/10.5642/jhummath.201802.21

- Smith, W. C. (2016). An introduction to the global testing culture. In W. C. Smith (Ed.), The global testing culture: Shaping educational policy, perceptions, and practice (pp. 7–24). Symposium Books.

- Swedish Government. (2017). Uppdrag att genomföra kompetensutvecklings- och implementeringsinsatser avseende en garanti för tidiga stödinsatser i förskoleklassen, grundskolan, specialskolan och sameskolan. (Governmetal decition on assessment material for Preschool-class, Compulsory school, Special school and Samí school). Regeringsbeslut, Regeringen, Utbildningsdepartementet. U2018/02959/S

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2021). Uppföljning av obligatoriska kartläggningsmaterial i förskoleklass och bedömningsstöd i årskurs. Rapport 2021:8.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). PM − Slutbetyg i grundskolan våren 2022.

- Swedish Research Council, Vetenskapsrådet. (2002). Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Swedish Research Council, Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). God forskningssed. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2020). Kartläggning och tidiga stödinsatser i förskoleklassen (Dnr: 400–2019:6183).

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2022). Årsrapport 2022. Erfarenhet från inspektion.

- Vennberg, H. (2015). Förskoleklass – ett år att räkna med. Förskoleklasslärares möjligheter att följa och analysera elevers kunskapsutveckling i matematik [Licentat dissertation]. Umeå University.

- Vennberg, H. (2020). Att räkna med alla elever: följa och främja matematiklärande i förskoleklass [Doctoral dissertation]. Umeå university.

- Watson, A. (2021). Care in mathematics education: Alternative educational spaces and practices. Palgrave Macmillan.