Abstract

Background

Abstinence has long been considered the defining feature of recovery from substance use disorder, with a focus on individual level factors associated with abstinence rather than identifying individual and socioecological factors that support recovery. This paper proposes greater consideration of dynamic behavioral ecological influences on recovery and offers an expanded contextualized approach to understanding and promoting recovery and predicting dynamic recovery pathways.

Methods

Conceptual and empirical bases are summarized that support moving beyond research, treatment, and policy agendas that focus narrowly on the individual as the fundamental change agent in recovery and that emphasize changes in substance use as the primary outcome metric. A model is presented that expands the scope of recovery-relevant variables to include dynamically-varying ecological contexts that variously support or hinder recovery along with an expanded scope of functional and contextual outcome variables.

Results

Examining behavior patterns through time in changing environmental contexts that include community and neighborhood-level variables and social determinants of health is critical for understanding recovery and developing multi-level interventions to promote change. Molar behavioral and ecological perspectives are needed to understand how recovery is influenced by broader contextual features in addition to individual determinants. This paper provides concrete recommendations for the pursuit of this broadened research agenda.

Conclusions

Individual pathology-based approaches to understanding and promoting substance use disorder recovery are too narrowly focused. This review calls for greater consideration of the dynamic behavioral ecological and temporally extended contexts that contribute to harmful substance use and systemic changes necessary to promote and sustain recovery.

Substance use disorder (SUD) research and treatment approaches have historically focused on substance use behavior and emphasized relapse prevention as the critical goal, with relapse commonly defined as a return to any drinking or drug use, and recovery defined as abstinence from any substance use (Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel Citation2007). More recent research has focused on the concept of recovery as a dynamic process that may include some engagement in substance use by an individual (Litten et al. Citation2012; Witkiewitz, Litten, et al. Citation2019; Hagman et al. Citation2022; Tucker and Witkiewitz Citation2022).

The dominant focus on the individual as the primary, if not sole, agent of change remains central to many contemporary models of addiction, such as the brain disease, cognitive behavioral, dual process, and reinforcer pathology models (Leshner Citation1997; Marlatt and Donovan Citation2005; Stacy and Wiers Citation2010; Bickel et al. Citation2014). These models emphasize causal determinants that are temporally contiguous with the discrete effect or act of interest, typically an individual’s alcohol or drug use in the immediate context, and often fail to consider the broader socioecological contexts that interact with changes in local or proximal environmental, social, and biological processes over time. Further, these models have not considered the multiple levels of influence on recovery that range from micro- to meso- to macro-variable domains (Tucker and Witkiewitz Citation2022). Correspondingly, outcome measures have been limited primarily to substance use and related harms.

In alignment with other recent papers critical of these prominent addiction models (Rachlin et al. Citation2018; Heather et al. Citation2022; Pickard Citation2022; Acuff et al. Citation2023; Tucker et al. Citation2023; Vuchinich et al. Citation2023), we propose an expanded perspective that is predicated on the fact that the etiology and maintenance of SUD, as well as recovery, are dynamic behavioral processes spread out in time and occur in broader environmental contexts that also are dynamic (Tucker and Witkiewitz Citation2022). Based on findings across the translational research continuum, Acuff et al. (Citation2023), Tucker et al. (Citation2023), and Vuchinich et al. (Citation2023), among others (e.g. Rachlin et al. Citation2018), have similarly argued for extending the socioecological model of health behavior (Institute of Medicine Citation2003) to harmful substance-related behaviors, which expands the scope of contextual variables to include interpersonal, neighborhood, community, economic, and policy level factors. This broadened perspective is well established in other health relevant fields (e.g. public health, medical sociology, health economics, see Burke et al. Citation2009), but has been relatively neglected in SUD research and practice. In investigating the broader contexts in which substance-related behaviors develop, evolve, and resolve, specific emphasis is placed on the role of relative constraints on access to substances vs. other available activities and commodities in the context of choice, broadly defined, with a goal of increasing access to substance-free alternatives that can reduce substance use. In this paper, we first summarize research that has considered individual-level, community-level, and broader environmental and policy-level influences on harmful substance use and recovery. We then introduce a new theoretical model of recovery and provide suggestions for future research to incorporate variable domains and methodologies useful for evaluating aspects of the proposed dynamic behavioral ecological model of recovery.

Broadening variable domains in the study of substance use disorder

Early behavior therapists had a broad view of substance-related problems that encompassed substance use and life functioning (Pattison et al. Citation1977), and research on SUD etiology has acknowledged multiple layers of influence on its development (Jackson et al. Citation2006; Colder et al. Citation2013; Rothenberg et al. Citation2019; Boness et al. Citation2021). However, this perspective has not been well represented in SUD treatment outcome studies or studies of recovery in recent decades. Instead, the field has moved toward greater emphasis on brain disease models (Goldstein and Volkow Citation2011; Volkow et al. Citation2016; Heilig et al. Citation2021) or psychological states (e.g. anxiety, craving, cognitive expectancies) that immediately precede discrete substance use episodes (Marlatt and Gordon Citation1985; Leonard and Blane Citation1999). Although recent reviews have acknowledged the need to broaden definitions of recovery to incorporate well-being, functioning, social, and other environmental factors (Kelly et al. Citation2018; Tucker et al. Citation2020; Witkiewitz et al. Citation2020; Heilig et al. Citation2021; Hagman et al. Citation2022; Acuff et al. Citation2023), as well as understanding and promoting positive behavior change within broader socioecological contexts (Rachlin et al. Citation2018; Acuff et al. Citation2023; Tucker et al. Citation2023; Vuchinich et al. Citation2023), comprehensive approaches to conceptualizing and studying these multiple levels of influence are under-developed. Critical gaps remain in understanding how SUD-related risks and recovery processes and outcomes may co-vary with these broader domains. These gaps have been partially addressed by the recovery capital literature, which has provided growing evidence for the value of socioecological approaches to studying SUD recovery and the strengths and assets a person experiences to support recovery (Cloud and Granfield Citation2008; Best Citation2017; Vilsaint et al. Citation2017; Best et al. Citation2020; Best and Hennessy Citation2022).

In summary, recently proposed theoretical and empirical models of SUD and recovery have sought to move beyond an individual pathology-oriented focus and to broaden the scope of relevant variable domains to encompass environmental factors at multiple levels. However, the complexities of pursuing these broadened domains require greater consideration of multiple levels of influence and how multilevel influences can be brought together to promote recovery. As outlined more fully in a recent edited volume (Tucker and Witkiewitz Citation2022), the socioecological model of health behavior offers a useful preliminary organizational model for considering the relevant research.

Socioecological model of health behavior applied to substance use disorders

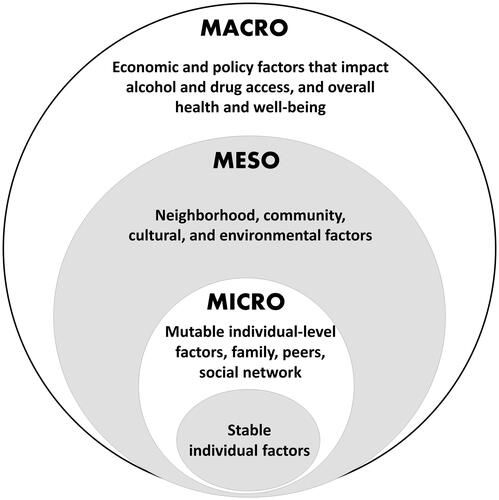

The socioecological model of health behavior (Institute of Medicine Citation2003) has provided an organizing framework in public health for delineating the multiple levels of influence on individual health behaviors and outcomes. As illustrates, an individual is at the center of an outwardly expanding series of concentric circles of influence, including family, friends, and social networks; organizations, communities, and culture; and government policies, laws, and regulations. The model acknowledges that social and structural determinants influence health behavior (World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health Citation2008) and can also be leveraged for health promotion. Social determinants of health are associated with many behavioral health disorders (Bondy and Rehm Citation1998; Todman and Diaz Citation2014; Compton and Shim Citation2015; Sterling et al. Citation2018) and have utility beyond individual level determinants in predicting outcomes and promoting whole person health and functioning (Link and Phelan Citation1995). Research relevant to SUD and recovery is summarized next ranging from research on individual micro level factors that focus on the individual as change agent, meso level factors that focus on understanding and promoting individual change within community and neighborhood environments, and macro level factors involved in creating environments, resources, incentives, and policies to reduce substance-related harms and promote recovery.

Figure 1. Socioecological model of factors that may promote or hinder substance use disorder recovery in context.

Individual micro level factors

Stable individual factors that are largely immutable when an individual develops a SUD have been well investigated for decades, including genetic influences, family history, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and neurobiological factors that predict risk for SUD development and may hinder or promote recovery (Crews and Boettiger Citation2009; Schuckit and Smith Citation2011; Cui et al. Citation2015; Morean et al. Citation2015; Wall et al. Citation2016; Borgert et al. Citation2023). In contrast, much research on recovery has focused on potentially changeable factors that may be targeted at the individual level, including negative emotionality, coping, craving, cognition (e.g. expectancies, self-efficacy), physical health (Witkiewitz and Marlatt Citation2004; Sliedrecht et al. Citation2019; Vilsaint et al. Citation2019), executive functioning (Bates et al. Citation2006, Citation2013), reward delay discounting, regulatory flexibility, and future orientation (Roos and Witkiewitz Citation2016; Snider et al. Citation2016; Athamneh et al. Citation2022; Craft et al. Citation2022; Keith et al. Citation2022). This large body of research on mutable individual factors has indicated that reducing negative emotionality and craving; improving self-efficacy, executive function, and coping flexibility, and reducing reward delay discounting and increasing future orientation are all associated with positive substance-related outcomes.

Environmental, community, and neighborhood meso-level factors

Behavioral economic studies of recovery began an expansion of focus toward understanding individual behavior in context and highlight that shifts in behavioral and resource allocation away from harmful substance use toward beneficial substance-free rewards are vital to promoting and maintaining positive behavior change (Acuff et al. Citation2019; Tucker et al. Citation2021, Citation2023; Vuchinich et al. Citation2023). Recent studies of recovery have considered life-functioning indicators (Witkiewitz, Wilson, et al. Citation2019), as well as the proportion of overall reinforcement received from alcohol-involved vs. alcohol-free rewards (Acuff et al. Citation2019; Kuhlemeier et al. Citation2024) and resource allocation (e.g. monetary spending) on alcohol vs. other commodities (Tucker et al. Citation2021). Recent research has also considered individual life circumstances surrounding risk for SUD and recovery attempts (e.g. life events, peer behavior) (Tucker et al. Citation2002, Citation2020) and social network drinking and peer recovery support (Kelly et al. Citation2014; Reif et al. Citation2014; Bassuk et al. Citation2016; Ashford et al. Citation2018; Kelly et al. Citation2018). These studies show substance-free activity engagement, association with peers who do not have SUD or engage in risky substance use, and relative resource allocation to beneficial substance-free activities and commodities are associated with positive outcomes.

Enriching the environment with substance-free rewards has well-documented salutary effects in reducing substance use in both humans and animals (Murphy et al. Citation2012; Venniro et al. Citation2021). The strength of preference for substance use varies inversely with the availability of and constraints on access to non-drug reinforcers, indicating that it is insufficient to only consider access to and consumption of substances. Rodents will often choose social rewards over drug rewards (Venniro et al. Citation2018, Citation2021), and both non-human animal and human studies have found increased access to alternative non-drug rewards and access to enriched environments are associated with decreased drug use (Lamb and Ginsburg Citation2018; Rodríguez-Ortega et al. Citation2019; Tucker et al. Citation2021; Maccioni et al. Citation2022; Kuhlemeier et al. Citation2024).

The role of neighborhood and built environment variables have been supported in studies of risk behaviors related to substance use, incarceration and arrests, obesity, inactivity, poor nutrition, and HIV infection (Latkin et al. Citation2013; Mair et al. Citation2019; Cambron et al. Citation2020; Camplain et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2020), among others. However, research is fairly incipient in the substance use field, with some notable recent exceptions (Astell-Burt and Feng Citation2019; Martin et al. Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2020; Berry et al. Citation2021). Recent studies have suggested that access to greenspace may improve mental health (Astell-Burt and Feng Citation2019), reduce alcohol craving (Martin et al. Citation2019), and increase engagement in opioid use disorder treatment (Berry et al. Citation2021). Conversely, impoverished neighborhoods may exacerbate adolescent behavior problems (Wang et al. Citation2020).

Environmental contexts have also been investigated in larger communities, and several recent studies have examined the influence of community-level factors on individual substance use and symptoms. For example, a return to problem drinking after treatment was predicted by the interaction of greater neighborhood disadvantage with the number of heavy drinkers in one’s social network (Mericle et al. Citation2018). Similarly, greater neighborhood poverty and greater density of alcohol outlets predicted increased alcohol use disorder (AUD) symptom trajectories among individuals recruited from treatment settings (Karriker-Jaffe et al. Citation2020). Sober living houses with greater proximity to treatment and recovery resources were found to also have a higher density of alcohol outlets (Mericle et al. Citation2016, Citation2020). Thus, neighborhood characteristics that may support recovery, including proximity and availability of recovery resources, may also be associated with heightened environmental risk for worse recovery outcomes, including proximity and availability of alcohol outlets.

Economic and policy macro-level factors

Research in sociology, epidemiology, health and behavioral economics has identified even broader contextual domains associated with substance- and health-related outcomes. In the alcohol field, variables pertinent to alcohol access, alcohol costs, socioeconomic status, and health care access have been most extensively researched and supported in relation to drinking-specific outcomes (Babor et al. Citation2010; Cook and Cherpitel Citation2012; Karriker-Jaffe et al. Citation2012; Roche et al. Citation2015; Xuan et al. Citation2015; Cambron et al. Citation2020; Karriker-Jaffe et al. Citation2020; Lee et al. Citation2020; Mair et al. Citation2020; Cook et al. Citation2021; Kerr and Subbaraman Citation2021; Swan et al. Citation2021; Tomko et al. Citation2022; Wiley et al. Citation2022). Communities with lower socioeconomic status have higher densities of alcohol outlets and experience more consequences from alcohol consumption, even though higher socioeconomic communities consume more alcohol (Galea et al. Citation2007; Bryden et al. Citation2013; Roche et al. Citation2015; Trangenstein et al. Citation2020).

Few studies have investigated social determinants of health at higher levels of influence (e.g. communities, government) on recovery. A large cohort study (N = 52,499) found individuals were less likely to achieve remission six months after community-based AUD treatment if they lived in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage and housing instability (Peacock et al. Citation2018). Another study found lower community-level income inequality and higher health insurance rates within communities predicted recovery following AUD treatment (Swan et al. Citation2021).

Intervening across levels of the socioecological model

To improve health and reduce substance-related problems in the general population, it is critical to study and intervene in the broader systems surrounding recovery and to gain a better understanding of how behavior reliably covaries over time with shifts in the environmental context. This requires researchers to investigate and measure the patterning of behavior and dynamic transitions in behavior that occur in context over time. A key feature that draws from molar behavioral theories of choice is the focus on alternatives to addictive behaviors and the fostering of enriched environments that provide ample opportunities for accessing substance-free reinforcement (Acuff et al. Citation2023; Tucker et al. Citation2023; Vuchinich et al. Citation2023). Intervening to increase engagement with substance free activities has been associated with reductions in drinking and time allocated to drinking among heavy drinkers (Murphy et al. Citation2019).

The Icelandic Prevention Model (Kristjansson et al. Citation2020) is an example of targeting an entire community system to change alcohol and other substance use behavior among youth, whereby the community itself was the primary intervention target. Components of the model targeted greater parental monitoring, enhancing peer relationships, improving access to social and leisure activities, as well as strengthening alcohol policy and youth curfews. Substantial decreases in alcohol use initiation and other drug use occurred during the 20 years of the program (Kristjansson et al. Citation2021).

Dynamic behavioral ecological model of substance use disorder and recovery

The socioecological model of health behavior () is useful for providing organizational structure for levels of environmental influences on SUD recovery as described above. However, it does not address dynamic changes and interactions within and across levels of the model over time. This is fundamental to understanding recovery processes in ongoing context that can guide coordinated intervention development and implementation within and across levels that may have potentially greater aggregate benefits than single level interventions delivered without consideration of other levels of influence.

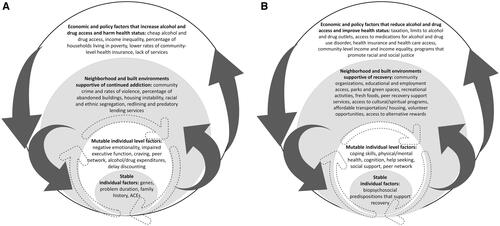

Therefore, we propose the dynamic behavioral ecological model of SUD and recovery shown in that expands on the socioecological model by acknowledging and incorporating the dynamic and nonlinear nature of behavior change, which can occur abruptly and seemingly without clear deterministic predictors. adds dynamic bidirectional shifts (dark grey arrows) across levels of the socioecological model and also acknowledges feedback loops in individual behavior influenced by environmental factors (dashed arrows). Following the research considered above, Panel A summarizes influences on SUD development and maintenance, and Panel B summarizes influences on SUD recovery, which overlap but are not identical.

Figure 2. Dynamic behavioral ecological model of person-specific substance use disorder (A) and recovery (B) pathways in context.

Given the dynamic nature of these influences, it is clear that any one predictor (e.g. affect) is unlikely to reliably determine the behavior of the ecological system for all individuals in recovery. Like many ecological systems, humans also react to changing conditions in the environment with the potential for drastic and dynamic transitions in states of the system. This is termed a ‘regime shift’ in ecological systems (p. 595; Scheffer et al. Citation2001). Change is not exclusively incremental and can be abrupt and sudden (Miller Citation2004; Witkiewitz and Marlatt Citation2007; Holzhauer et al. Citation2017). We believe that it is important to expand beyond questions of what causes specific transitions and move toward questions of when and how the entire system transitions, as well as the timing of dynamic shifts for the entire ecosystem (i.e. regime shifts). These regime shifts may be influenced by any number or combination of factors and their interaction within and across levels of the environmental and cultural context.

This approach will require a greater focus on studying broader environmental contexts over time that support harmful substance use and the environmental contexts and system changes that promote and sustain recovery. Individuals may be struggling with problems related to substance use, may be experiencing health concerns and interpersonal conflict, and may be predominately engaging in substance use and related activities. But a given individual also moves through the world within immediate and extended environmental contexts, and these contexts could either support ongoing substance-related problems, or dynamic shifts in the system could help move the individual toward recovery. Over time the broader system is shifting and influenced by and interacting with interpersonal factors, community supports, social determinants of health, lifestyle changes, and other environmental factors that collectively hinder or promote recovery.

For each person attempting recovery, there are potentially different SUD recovery pathways that are differentially influenced by individual, social network, environmental, and community-level factors over time. Further complicating the study of recovery is that the individual- and community-level factors that promote the maintenance of SUD over time () are not necessarily the absence or opposite of individual-level and community-level factors that may support recovery over time (). The mere absence of factors that promote and maintain harmful substance use will not assure transitioning to recovery, and other aspects of the environment may be needed to support recovery (Pouille et al. Citation2021). For example, in many natural environments, easy access to substances remains unchanged, but recovery occurs as features of the environment shift toward offering substance-free activities and commodities that can compete with substance use. As research on behavioral choice and behavioral economics has robustly demonstrated, preference for a substance can be reduced by enriching the environment with alternative rewards even if substance availability remains unchanged (Murphy et al. Citation2021; Acuff et al. Citation2023; Tucker et al. Citation2023; Vuchinich et al. Citation2023).

Critically, recovery pathways may be more or less available to some people depending on relatively mutable and more static characteristics of the individual and their environmental context. Any given individual may be differentially impacted by different environmental circumstances, which is why recovery is not a one size fits all process and why different individuals may experience greater or lesser set-backs in a recovery journey (Pouille et al. Citation2021). Greater economic resources, access to substance free reinforcement, social network support for recovery goals, and availability of recovery resources in a community may facilitate a less difficult recovery pathway. Lack of these resources, built environments with few substance-free reinforcers, social networks supportive of harmful substance use, and systemic biases in access to social, economic, and policy resources (e.g. due to racism, sexism, and agism) will likely make a recovery path more difficult.

At any point in the timeline, one could measure associations between an individual’s environment and their functioning, which would provide a narrow and temporally limited (‘dipstick’) understanding of an individual’s status and would ignore or seriously oversimplify an ongoing contextualized process. To better understand the recovery context, it is important to look more broadly at how the entire system is changing and when aspects of the system co-vary and interact with one another over time (Rachlin et al. Citation2018; Tucker et al. Citation2023). A complex adaptive systems approach may be useful for understanding recovery dynamics within ecological contexts and interactions between the multiple levels of influence that are bidirectional (Hufford et al. Citation2003; Witkiewitz and Marlatt Citation2007; Levy et al. Citation2009; Grasman et al. Citation2016; Duncan et al. Citation2019). This approach explicitly acknowledges that individual choices and patterns of behavior evolve and change in nonlinear ways over time, with bidirectional interactions between the person and the environment, creating feedback loops. The concept of emergence is a key feature of complex adaptive systems and also is a feature of recovery. Interactions between an individual and the environment can produce novel (i.e. emergent) behavior in seemingly unpredictable ways. Miller (Citation2004) described the emergence of AUD recovery in his work on quantum change. Further, alcohol treatment outcome studies (Holzhauer et al. Citation2017) have reported abrupt decreases in drinking, and research on depression and anxiety (Aderka et al. Citation2012; Helmich et al. Citation2020) has observed sudden gains or nonlinear change in symptoms across weeks of treatment.

Investigating the dynamic behavioral ecological model of substance use disorder and recovery

In brief, the proposed dynamic behavioral ecological model proposes the following testable hypotheses: (1) There are individual differences in recovery pathways (i.e. heterogeneity) and in environment-behavior patterning over time; (2) environment-behavior patterning over time occurs at different rates for different individuals, and rates and patterns of environment-behavior patterning also change within individuals over time; (3) forces outside of the individual can affect the rate and timing of environment-behavior patterning; and (4) behavior is emergent, such that there are nonlinearities in how and when forces outside of and within the individual may affect change. As discussed next, analytic approaches are available to test these hypotheses as applied to SUD recovery, as well as other mental health disorders (Fried and Robinaugh Citation2020; van der Wal et al. Citation2021).

provides guidance for empirical investigation of aspects of the dynamic behavioral ecological model of recovery, ranging from minimal to ideal approaches, that should advance knowledge of recovery in context, including variable domains, measurement approaches, and analytic methods for studying the model. Studying environment-behavior patterning over time is fundamental using either prospective longitudinal designs or retrospective designs with measures, such as the Timeline Follow-Back method that assess past associations and changes in associations over time (Tucker et al. Citation2021). At a minimum, we encourage researchers whose work focuses primarily on micro-level factors to collect information on socioecological contexts and broader measures of the environment that may influence individual behavior as well as individual-environment interactions. In human research, a plethora of information on contextual and environmental features can be ascertained from postal codes and other geographic location indicators (e.g. U.S. Census tract data) and from brief measures of social resources, recovery capital, time and financial allocations, and activity engagement (McKay et al. Citation1993; Beattie and Longabaugh Citation1999; Tucker et al. Citation2009; Gundersen and Ziliak Citation2015; Vilsaint et al. Citation2017). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA), passive sensing, and other intensive longitudinal data collection methods are useful for ascertaining behavioral patterning and molar environmental-behavior relationships over time in context (Wycoff et al. Citation2018; Wright and Zimmermann Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2022; Stone et al. Citation2023).

Table 1. Guidance for examining the dynamic behavioral ecological model of recovery.

Qualitative work is essential to assess the needs of specific individuals and contextual influences within communities, and identify the availability and types of substance-free activities and commodities that will support recovery in that community. For example, using qualitative methods and community-engaged research, many individuals in recovery have identified broader goals and social determinants of health as essential to recovery support, including housing, health care, parenting advice and family strengthening, and access to meaningful activities (Collins et al. Citation2015; Eaves et al. Citation2022; Hussong et al. Citation2022).

Quantitative work that incorporates multiple levels of analysis to capture the system dynamics that unfold in socioecological contexts over time are needed to understand recovery. As noted earlier, we see great utility in a complex adaptive systems approach that acknowledges nonlinear change, emergence, and feedback loops in the process of recovery (Hufford et al. Citation2003; Witkiewitz and Marlatt Citation2007; Levy et al. Citation2009; Grasman et al. Citation2016; Duncan et al. Citation2019). Several nonlinear dynamical systems models can variously accommodate nonlinearity in inter- and intraindividual differences in parameter estimates over time, such as the modified Van der Pol oscillator model (Chow et al. Citation2016), systems engineering approaches (Wiers and Verschure Citation2021), and time series approaches (e.g. group iterative multiple model estimation; Gates and Molenaar Citation2012) that allow for examining subgrouping and shared vs. individual differences (Lane et al. Citation2019; Park et al. Citation2023). Network modeling may be useful for studying feedback loops that may occur at the individual-level of the system (Robinaugh et al. Citation2020; Borsboom, Deserno, et al. Citation2021). Network analyses and machine learning approaches may be valuable in reducing the dimensionality of potential variables across levels of analysis (van der Wal et al. Citation2021).

The cusp catastrophe model has been applied to study dynamics in individual relapse risk among patients with AUD (Witkiewitz et al. Citation2007; Chow et al. Citation2015) and may be expanded to consider social and environmental network dynamics (Grasman et al. Citation2016; van der Maas et al. Citation2020). The cusp catastrophe model is particularly useful for predicting behavior that changes either slowly and linearly or abruptly and nonlinearly with small changes in the input parameters. Chow et al. (Citation2015) developed a regime switching model which estimates the properties of the cusp catastrophe model within a latent variable framework, and this model has recently been extended to a Bayesian multilevel approach (Li et al. Citation2022), which may be particularly useful for studying individuals nested within contexts over time.

Using the methods described above, we could envision a study that would test the dynamic behavioral ecological model by assessing patterns of behavior in context over time (either retrospectively using the Timeline Follow-Back method, such as Tucker et al. (Citation2021); or prospectively using EMA) with community and environmental information collected via postal codes or global positioning system data. First, network analyses (or machine learning) could be used to reduce the dimensionality of correlated predictors (van der Wal et al. Citation2021; Kosztyán et al. Citation2022). Next, multilevel regime switching models (Chow et al. Citation2015; Li et al. Citation2022) could accommodate individual heterogeneity in recovery pathways, incorporate random effects to allow different rates and patterns of change within and between individuals over time (Chow et al. Citation2016), estimate the time-varying impact of peer, community, and environmental-level variables at level 2 of the multilevel model, and test cross-level interactions, whereby peer, community, and environmental-level variables affect the association between individual predictors and outcomes. This model could also capture emergent changes in the system (e.g. a rapid transition to recovery with small changes in predictors at any level of analysis).

Summary and future directions

In summary, we argue for the field of SUD recovery research to consider the dynamic behavioral and ecological contexts that support or hinder recovery and to broaden the scope of variable domains assessed with respect to contextual features and substance-related outcomes of interest. This will require a greater focus on measuring the extended patterns of substance use-relevant behavior and changes in the surrounding socioecological systems, as well as investigating factors that interact to change the dynamic characteristics of the system over time, including measures of functioning, well-being, environmental characteristics, and social determinants of health. Researchers could then use this information to identify what interventions and when those interventions may be most effective for shifting patterns of behavior at the individual level, taking into consideration neighborhood, community, and policy factors that may be associated with transitions in behavioral patterning over time. This is not to say that each and every study needs to assess all such variables or that they need to or can be targeted for change through interventions. Rather, developing a collective body of empirical work on the multiple levels of the dynamic behavioral ecological model can guide future research and investment in contexts to promote SUD recovery, appreciating that some contextual features lie beyond what a practitioner, community, government, or policy-maker can alter. Other research fields have been successfully used socioecological approaches to explicitly study multi-level contextual factors and behavior patterns extended in time, including excellent work on neighborhood level factors and HIV prevention and treatment (Latkin et al. Citation2013; White et al. Citation2020; Brawner et al. Citation2022) and how social contexts may dynamically impact health behavior (Burke et al. Citation2009).

Clearly, delineating levels of analysis in statistical and mathematical models may provide new insights for the prediction of recovery regime shifts (Witkiewitz and Marlatt Citation2007; Chow et al. Citation2015; Grasman et al. Citation2016; Borsboom, van der Maas, et al. Citation2021; Soyster et al. Citation2022; van den Ende et al. Citation2022). Ascertaining the broader contextual variables in measurable ways that can be related to individual trajectories of behavior change is the question at hand for recovery research. Collecting postal codes on individual research participants allows investigators to put their findings into a broader socioecological context, even if that is not the primary purpose of the research. If the field adopts this practice as a basic research component, over time the knowledge base for understanding SUD and recovery in context will inevitably grow and suggest more focused research questions. This expanded research framework may lead to greater recovery support and new research findings that are aligned with the complex descriptions of dynamic recovery pathways offered by individuals with lived experience of SUD and recovery from the disorder (Dingle et al. Citation2015; Shortt et al. Citation2017; Smith Citation2022; Stull et al. Citation2022).

Research on SUD recovery has largely been built on moralistic and paternalistic models that hold individuals with SUD responsible for causing and resolving their problem behavior with little to no recognition of the broader behavioral patterns and environmental and systemic factors that support or hinder recovery. Little attention has been given to how these factors dynamically interact over time and how they can be changed or leveraged to improve recovery outcomes. We believe that looking beyond the individual, changes in consumption, and treatment as the primary research foci and expanding recovery definitions and studying multilevel influences on recovery are fundamental to advancing the science and practice of substance-related behavior change. The current paper provides a theoretical model, testable hypotheses, and methods for tackling these broader research questions in future research and should advance understanding of SUD and how people can be supported in recovery over time.

Ethical statement

The research in this paper does not require ethics board approval.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ricardo González-Pinzón, Han van der Maas, and Rudy E. Vuchinich for insightful and tremendously helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

Drs. Witkiewitz and Tucker have recently published an edited volume on the topic of recovery from alcohol use disorder (https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108976213), and both receive funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to conduct research examining recovery processes and mechanisms of behavior change.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acuff SF, Dennhardt AA, Correia CJ, Murphy JG. 2019. Measurement of substance-free reinforcement in addiction: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 70:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.003.

- Acuff SF, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. 2023. A contextualized reinforcer pathology approach to addiction. Nat Rev Psychol. 2(5):309–323. doi: 10.1038/s44159-023-00167-y.

- Aderka IM, Nickerson A, Bøe HJ, Hofmann SG. 2012. Sudden gains during psychological treatments of anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 80(1):93–101. doi: 10.1037/a0026455.

- Ashford RD, Curtis B, Brown AM. 2018. Peer-delivered harm reduction and recovery support services: initial evaluation from a hybrid recovery community drop-in center and syringe exchange program. Harm Reduct J. 15(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0258-2.

- Astell-Burt T, Feng X. 2019. Association of urban green space with mental health and general health among adults in Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2(7):e198209. doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2019.8209.

- Athamneh LN, Freitas Lemos R, Basso JC, Tomlinson DC, Craft WH, Stein MD, Bickel WK. 2022. The phenotype of recovery II: the association between delay discounting, self-reported quality of life, and remission status among individuals in recovery from substance use disorders. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 30(1):59–72. doi: 10.1037/pha0000389.

- Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, Grube JW, Hill L, Holder H, Homel R, et al. 2010. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity: research and public policy. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Bassuk EL, Hanson J, Greene RN, Richard M, Laudet A. 2016. Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 63:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003.

- Bates ME, Buckman JF, Nguyen TT. 2013. A role for cognitive rehabilitation in increasing the effectiveness of treatment for alcohol use disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 23(1):27–47. doi: 10.1007/s11065-013-9228-3.

- Bates ME, Pawlak AP, Tonigan JS, Buckman JF. 2006. Cognitive impairment influences drinking outcome by altering therapeutic mechanisms of change. Psychol Addict Behav. 20(3):241–253. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.241.

- Beattie MC, Longabaugh R. 1999. General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addict Behav. 24(5):593–606. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00120-8.

- Berry MS, Rung JM, Crawford MC, Yurasek AM, Ferreiro AV, Almog S. 2021. Using greenspace and nature exposure as an adjunctive treatment for opioid and substance use disorders: preliminary evidence and potential mechanisms. Behav Processes. 186:104344. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2021.104344.

- Best D. 2017. Developing strengths-based recovery systems through community connections. Addiction. 112(5):759–761. doi: 10.1111/add.13588.

- Best D, Hennessy EA. 2022. The science of recovery capital: where do we go from here? Addiction. 117(4):1139–1145. doi: 10.1111/add.15732.

- Best DW, Vanderplasschen W, Nisic M. 2020. Measuring capital in active addiction and recovery: the development of the strengths and barriers recovery scale (SABRS). Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 15(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00281-7.

- Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. 2007. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. J Subst Abuse Treat. 33(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001.

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. 2014. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 10(1):641–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724.

- Bondy S, Rehm J. 1998. The interplay of drinking patterns and other determinants of health. Drug Alcohol Rev. 17(4):399–411. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187241.

- Boness CL, Watts AL, Moeller KN, Sher KJ. 2021. The etiologic, theory-based, ontogenetic hierarchical framework of alcohol use disorder: a translational systematic review of reviews. Psychol Bull. 147(10):1075–1123. doi: 10.1037/bul0000333.

- Borgert B, Morrison DG, Rung JM, Hunt J, Teitelbaum S, Merlo LJ. 2023. The association between adverse childhood experiences and treatment response for adults with alcohol and other drug use disorders. Am J Addict. 32(3):254–262. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13366.

- Borsboom D, Deserno MK, Rhemtulla M, Epskamp S, Fried EI, McNally RJ, Robinaugh DJ, Perugini M, Dalege J, Costantini G, et al. 2021. Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nat Rev Methods Primer. 1(1):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s43586-021-00055-w.

- Borsboom D, van der Maas HLJ, Dalege J, Kievit RA, Haig BD. 2021. Theory construction methodology: a practical framework for building theories in psychology. Perspect Psychol Sci. 16(4):756–766. doi: 10.1177/1745691620969647.

- Brawner BM, Kerr J, Castle BF, Bannon JA, Bonett S, Stevens R, James R, Bowleg L. 2022. A systematic review of neighborhood-level influences on HIV vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 26(3):874–934. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03448-w.

- Bryden A, Roberts B, Petticrew M, McKee M. 2013. A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health Place. 21:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012.

- Burke NJ, Joseph G, Pasick RJ, Barker JC. 2009. Theorizing social context: rethinking behavioral theory. Health Educ Behav. 36(5 Suppl):55S–70S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109335338.

- Cambron C, Kosterman R, Rhew IC, Catalano RF, Guttmannova K, Hawkins JD. 2020. Neighborhood structural factors and proximal risk for youth substance use. Prev Sci. 21(4):508–518. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01072-8.

- Camplain R, Camplain C, Trotter RT, Pro G, Sabo S, Eaves E, Peoples M, Baldwin JA. 2020. Racial/ethnic differences in drug-and alcohol-related arrest outcomes in a southwest county from 2009 to 2018. Am J Public Health. 110(S1):S85–S92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305409.

- Chow S-M, Lu Z, Sherwood A, Zhu H. 2016. Fitting nonlinear ordinary differential equation models with random effects and unknown initial conditions using the stochastic approximation expectation-maximization (SAEM) algorithm. Psychometrika. 81(1):102–134. doi: 10.1007/s11336-014-9431-z.

- Chow S-M, Witkiewitz K, Grasman R, Maisto SA. 2015. The cusp catastrophe model as cross-sectional and longitudinal mixture structural equation models. Psychol Methods. 20(1):142–164. doi: 10.1037/a0038962.

- Cloud W, Granfield R. 2008. Conceptualizing recovery capital: expansion of a theoretical construct. Subst Use Misuse. 43(12–13):1971–1986. doi: 10.1080/10826080802289762.

- Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Hawk LW. 2013. Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 41(4):667–677. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0.

- Collins SE, Jones CB, Hoffmann G, Nelson LA, Hawes SM, Grazioli VS, Mackelprang JL, Holttum J, Kaese G, Lenert J, et al. 2015. In their own words: content analysis of pathways to recovery among individuals with the lived experience of homelessness and alcohol use disorders. Int J Drug Policy. 27:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.003.

- Compton MT, Shim RS. 2015. The social determinants of mental health. Focus. 13(4):419–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20150017.

- Cook WK, Cherpitel C. 2012. Access to health care and heavy drinking in patients with diabetes or hypertension: implications for alcohol interventions. Subst Use Misuse. 47(6):726–733. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.665558.

- Cook WK, Li L, Greenfield TK, Patterson D, Naimi T, Xuan Z, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. 2021. State alcohol policies, binge drinking prevalence, socioeconomic environments and alcohol’s harms to others: a mediation analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 56(3):360–367. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa073.

- Craft WH, Tegge AN, Athamneh LN, Tomlinson DC, Freitas-Lemos R, Bickel WK. 2022. The phenotype of recovery VII: delay discounting mediates the relationship between time in recovery and recovery progress. J Subst Abuse Treat. 136:108665. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108665.

- Crews F, Boettiger C. 2009. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 93(3):237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018.

- Cui C, Noronha A, Warren KR, Koob GF, Sinha R, Thakkar M, Matochik J, Crews FT, Chandler LJ, Becker HC, et al. 2015. Brain pathways to recovery from alcohol dependence. Alcohol. 49(5):435–452. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.04.006.

- Dingle GA, Cruwys T, Frings D. 2015. Social identities as pathways into and out of addiction. Front Psychol. 6:1795. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01795.

- Duncan JP, Aubele-Futch T, McGrath M. 2019. A fast-slow dynamical system model of addiction: predicting relapse frequency. SIAM J Appl Dyn Syst. 18(2):881–903. doi: 10.1137/18M121410X.

- Eaves ER, Doerry E, Lanzetta SA, Kruithoff KM, Negron K, Dykman K, Thoney O, Harper CC. 2022. Applying user-centered design in the development of a supportive mHealth app for women in substance use recovery. Am J Health Promot. 37(1):56–64. doi: 10.1177/08901171221113834.

- van den Ende MWJ, Epskamp S, Lees MH, van der Maas HLJ, Wiers RW, Sloot PMA. 2022. A review of mathematical modeling of addiction regarding both (neuro-) psychological processes and the social contagion perspectives. Addict Behav. 127:107201. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107201.

- Fried EI, Robinaugh DJ. 2020. Systems all the way down: embracing complexity in mental health research. BMC Med. 18(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01668-w.

- Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Vlahov D. 2007. Neighborhood income and income distribution and the use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. Am J Prev Med. 32(6 Suppl):S195–S202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.003.

- Gates KM, Molenaar PCM. 2012. Group search algorithm recovers effective connectivity maps for individuals in homogeneous and heterogeneous samples. Neuroimage. 63(1):310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.026.

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. 2011. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 12(11):652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119.

- Grasman J, Grasman RPPP, Van Der Maas HLJ. 2016. The dynamics of addiction: craving versus self-control. PLOS One. 11(6):e0158323. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0158323.

- Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. 2015. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 34(11):1830–1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645.

- Hagman BT, Falk D, Litten R, Koob GF. 2022. Defining recovery from alcohol use disorder: development of an NIAAA research definition. Am J Psychiatry. 179(11):807–813. doi: 10.1176/APPI.AJP.21090963.

- Heather N, Field M, Moss AC, Satel SL, editors. 2022. Evaluating the brain disease model of addiction. London: Routledge. [accessed 2022 May 24]. https://www.routledge.com/Evaluating-the-Brain-Disease-Model-of-Addiction/Heather-Field-Moss-Satel/p/book/9780367470067.

- Heilig M, MacKillop J, Martinez D, Rehm J, Leggio L, Vanderschuren LJMJ. 2021. Addiction as a brain disease revised: why it still matters, and the need for consilience. Neuropsychopharmacology. 46(10):1715–1723. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-00950-y.

- Helmich MA, Wichers M, Olthof M, Strunk G, Aas B, Aichhorn W, Schiepek G, Snippe E. 2020. Sudden gains in day-to-day change: revealing nonlinear patterns of individual improvement in depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 88(2):119–127. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000469.

- Holzhauer CG, Epstein EE, Hayaki J, Marinchak JS, McCrady BS, Cook SM. 2017. Moderators of sudden gains after sessions addressing emotion regulation among women in treatment for alcohol use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 83:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.09.014.

- Hufford MR, Witkiewitz K, Shields AL, Kodya S, Caruso JC. 2003. Relapse as a nonlinear dynamic system: application to patients with alcohol use disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 112(2):219–227. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.219.

- Hussong AM, Shadur JM, Sircar JK. 2022. Targeting the needs of families in recovery for addiction with young children. Child Youth Serv Rev. 143:106651. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106651.

- Institute of Medicine. 2003. Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professional for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press.

- Jackson KM, O'Neill SE, Sher KJ. 2006. Characterizing alcohol dependence: transitions during young and middle adulthood. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 14(2):228–244. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.228.

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Witbrodt J, Mericle AA, Polcin DL, Kaskutas LA. 2020. Testing a socioecological model of relapse and recovery from alcohol problems. Subst Abuse. 14:1178221820933631. doi: 10.1177/1178221820933631.

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb R, Bond J, Greenfield TK. 2012. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult alcohol outcomes: differential risk by race and gender. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 73(6):865–873. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.865.

- Keith DR, Tegge AN, Athamneh LN, Freitas-Lemos R, Tomlinson DC, Craft WH, Bickel WK. 2022. The phenotype of recovery VIII: association among delay discounting, recovery capital, and length of abstinence among individuals in recovery from substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 139:108783. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108783.

- Kelly JF, Abry AW, Milligan CM, Bergman BG, Hoeppner BB. 2018. On being “in recovery”: a national study of prevalence and correlates of adopting or not adopting a recovery identity among individuals resolving drug and alcohol problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 32(6):595–604. doi: 10.1037/adb0000386.

- Kelly JF, Stout RL, Greene MC, Slaymaker V. 2014. Young adults, social networks, and addiction recovery: post treatment changes in social ties and their role as a mediator of 12-step participation. PLOS One. 9(6):e100121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100121.

- Kerr WC, Subbaraman MS. 2021. Alcohol control policy and regulations to promote recovery from alcohol use disorder. In: Dynamic pathways to recovery from alcohol use disorder. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; p. 346–363. [accessed 2022 Jun 23]. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781108976213%23CN-bp-19/type/book_part.

- Kosztyán ZT, Kurbucz MT, Katona AI. 2022. Network-based dimensionality reduction of high-dimensional, low-sample-size datasets. Knowl Based Syst. 251:109180. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109180.

- Kristjansson AL, Lilly CL, Thorisdottir IE, Allegrante JP, Mann MJ, Sigfusson J, Soriano HE, Sigfusdottir ID. 2021. Testing risk and protective factor assumptions in the Icelandic model of adolescent substance use prevention. Health Educ Res. 36(3):309–318. doi: 10.1093/HER/CYAA052.

- Kristjansson AL, Mann MJ, Sigfusson J, Thorisdottir IE, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID. 2020. Development and guiding principles of the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promot Pract. 21(1):62–69. doi: 10.1177/1524839919849032.

- Kuhlemeier A, Tucker JA, Witkiewitz K. 2024. Role of relative reinforcement value of alcohol-free activities during recovery from alcohol use disorder in an adult clinical sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. doi: 10.1037/pha0000713.

- Lamb RJ, Ginsburg BC. 2018. Addiction as a BAD, a behavioral allocation disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 164:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2017.05.002.

- Lane ST, Gates KM, Pike HK, Beltz AM, Wright AGC. 2019. Uncovering general, shared, and unique temporal patterns in ambulatory assessment data. Psychol Methods. 24(1):54–69. doi: 10.1037/met0000192.

- Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. 2013. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 68(4):210–224. doi: 10.1037/A0032704.

- Lee JP, Ponicki W, Mair C, Gruenewald P, Ghanem L. 2020. What explains the concentration of off-premise alcohol outlets in Black neighborhoods? SSM Popul Health. 12:100669. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100669.

- Leonard KE, Blane HT. 1999. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York (NY): The Guilford Press.

- Leshner AI. 1997. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science. 278(5335):45–47. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.45.

- Levy YZ, Levy D, Meyer JS, Siegelmann HT. 2009. Drug addiction as a non-monotonic process: a multiscale computational model. In: Lim CT, Goh JCH, editors. 13th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (IFMBE Proceedings). Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer; p. 1688–1691.

- Li Y, Oravecz Z, Zhou S, Bodovski Y, Barnett IJ, Chi G, Zhou Y, Friedman NP, Vrieze SI, Chow S-M. 2022. Bayesian forecasting with a regime-switching zero-inflated multilevel Poisson regression model: an application to adolescent alcohol use with spatial covariates. Psychometrika. 87(2):376–402. doi: 10.1007/s11336-021-09831-9.

- Link BG, Phelan JC. 1995. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 35:80–94. doi: 10.2307/2626958.

- Litten RZ, Egli M, Heilig M, Cui C, Fertig JB, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Moss H, Huebner R, Noronha A. 2012. Medications development to treat alcohol dependence: a vision for the next decade. Addict Biol. 17(3):513–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00454.x.

- van der Maas HLJ, Dalege J, Waldorp L. 2020. The polarization within and across individuals: the hierarchical Ising opinion model. J Complex Netw. 8(2):cnaa010. doi: 10.1093/comnet/cnaa010.

- Maccioni P, Bratzu J, Lobina C, Acciaro C, Corrias G, Capra A, Carai MAM, Agabio R, Muntoni AL, Gessa GL, et al. 2022. Exposure to an enriched environment reduces alcohol self-administration in Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Physiol Behav. 249:113771. doi: 10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2022.113771.

- Mair C, Frankeberger J, Gruenewald PJ, Morrison CN, Freisthler B. 2019. Space and place in alcohol research. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 6(4):412–422. doi: 10.1007/s40471-019-00215-3.

- Mair C, Sumetsky N, Gruenewald PJ, Lee JP. 2020. Microecological relationships between area income, off-premise alcohol outlet density, drinking patterns, and alcohol use disorders: the east bay neighborhoods study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 44(8):1636–1645. doi: 10.1111/acer.14387.

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM, editors. 2005. Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Guildford Press.

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. 1985. Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in addictive behaviour change. New York (NY): Guilford.

- Martin L, Pahl S, White MP, May J. 2019. Natural environments and craving: the mediating role of negative affect. Health Place. 58:102160. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102160.

- McKay JR, Longabaugh R, Beattie MC, Maisto SA, Noel NE. 1993. Changes in family functioning during treatment and drinking outcomes for high and low autonomy alcoholics. Addict Behav. 18(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90037-a.

- Mericle AA, Karriker-Jaffe K, Patterson D, Mahoney E, Cooperman L, Polcin DL. 2020. Recovery in context: sober living houses and the ecology of recovery. J Commun Psychol. 48(8):2589–2607. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22447.

- Mericle AA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Gupta S, Sheridan DM, Polcin DL. 2016. Distribution and neighborhood correlates of sober living house locations in Los Angeles. Am J Community Psychol. 58(1–2):89–99. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12084.

- Mericle AA, Kaskutas LA, Polcin DL, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. 2018. Independent and interactive effects of neighborhood disadvantage and social network characteristics on problem drinking after treatment. J Soc Clin Psychol. 37(1):1–21. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2018.37.1.1.

- Miller WR. 2004. The phenomenon of quantum change. J Clin Psychol. 60(5):453–460. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20000.

- Morean ME, Corbin WR, Treat TA. 2015. Differences in subjective response to alcohol by gender, family history, heavy episodic drinking, and cigarette use: refining and broadening the scope of measurement. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 76(2):287–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.287.

- Murphy JG, Skidmore JR, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Murphy JG. 2012. A behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Addict Res Theory. 20(6):456–465. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.665965.

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Gex KS. 2021. Individual behavioral interventions to incentivize sobriety and enrich the natural environment with appealing alternatives to drinking. In: Tucker JA, Witkiewitz K, editors. Dynamic pathways to recovery from alcohol use disorder: meaning and methods. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Borsari B, Witkiewitz K, Meshesha LZ. 2019. A randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a brief alcohol intervention supplemented with a substance-free activity session or relaxation training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 87(7):657–669. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000412.

- Park JJ, Fisher ZF, Chow S-M, Molenaar PCM. 2023. Evaluating discrete time methods for subgrouping continuous processes. Multivariate Behav Res. 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2023.2235685.

- Pattison EM, Sobell MB, Sobell LC, editors. 1977. Toward an emergent model. In: Emerging concepts of alcohol dependence. New York (NY): Springer; p. 189–211.

- Peacock A, Eastwood B, Jones A, Millar T, Horgan P, Knight J, Randhawa K, White M, Marsden J. 2018. Effectiveness of community psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder: a national observational cohort study in England. Drug Alcohol Depend. 186:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.019.

- Pickard H. 2022. Is addiction a brain disease? A plea for agnosticism and heterogeneity. Psychopharmacology. 239(4):993–1007. doi: 10.1007/S00213-021-06013-4.

- Pouille A, Bellaert L, Vander Laenen F, Vanderplasschen W. 2021. Recovery capital among migrants and ethnic minorities in recovery from problem substance use: an analysis of lived experiences. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(24):13025. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413025.

- Rachlin H, Green L, Vanderveldt A, Fisher E. 2018. Behavioral medicine’s roots in behaviorism: concepts and applications. In: Fisher EB, Cameron LD, Christensen AJ, Ehlert U, Guo Y, Oldenburg B, Snoek FJ, editors. Principles and concepts of behavioral medicine: a global handbook. New York (NY): Springer; p. 241–275.

- Reif S, Braude L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Salim O, Delphin-Rittmon ME. 2014. Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 65(7):853–861. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400047.

- Robinaugh DJ, Hoekstra RHA, Toner ER, Borsboom D. 2020. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol Med. 50(3):353–366. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003404.

- Roche A, Kostadinov V, Fischer J, Nicholas R, O'Rourke K, Pidd K, Trifonoff A. 2015. Addressing inequities in alcohol consumption and related harms. Health Promot Int. 30(Suppl 2):ii20–ii35. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav030.

- Rodríguez-Ortega E, Alcaraz-Iborra M, de la Fuente L, de Amo E, Cubero I. 2019. Environmental enrichment during adulthood reduces sucrose binge-like intake in a high drinking in the dark phenotype (HD) in C57BL/6J mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 13:27. doi: 10.3389/FNBEH.2019.00027/BIBTEX.

- Roos CR, Witkiewitz K. 2016. Adding tools to the toolbox: the role of coping repertoire in alcohol treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 84(7):599–611. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000102.

- Rothenberg WA, Sternberg A, Blake A, Waddell J, Chassin L, Hussong A. 2019. Identifying adolescent protective factors that disrupt the intergenerational transmission of cannabis use and disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 34(8):864–876. doi: 10.1037/adb0000511.

- Scheffer M, Carpenter S, Foley JA, Folke C, Walker B. 2001. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature. 413(6856):591–596. doi: 10.1038/35098000.

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. 2011. Onset and course of alcoholism over 25 years in middle class men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 113(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017.

- Shortt NK, Rhynas SJ, Holloway A. 2017. Place and recovery from alcohol dependence: a journey through photovoice. Health Place. 47:147–155. doi: 10.1016/J.HEALTHPLACE.2017.08.008.

- Sliedrecht W, de Waart R, Witkiewitz K, Roozen HG. 2019. Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 278:97–115. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.038.

- Smith KE. 2022. Disease and decision. J Subst Abuse Treat. 142:108874. doi: 10.1016/J.JSAT.2022.108874.

- Snider SE, LaConte SM, Bickel WK. 2016. Episodic future thinking: expansion of the temporal window in individuals with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 40(7):1558–1566. doi: 10.1111/acer.13112.

- Soyster PD, Ashlock L, Fisher AJ. 2022. Pooled and person-specific machine learning models for predicting future alcohol consumption, craving, and wanting to drink: A demonstration of parallel utility. Psychol Addict Behav. 36(3):296–306. doi: 10.1037/adb0000666.

- Stacy AW, Wiers RW. 2010. Implicit cognition and addiction: a tool for explaining paradoxical behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 6(1):551–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131444.

- Sterling S, Chi F, Weisner C, Grant R, Pruzansky A, Bui S, Madvig P, Pearl R. 2018. Association of behavioral health factors and social determinants of health with high and persistently high healthcare costs. Prev Med Rep. 11:154–159. doi: 10.1016/J.PMEDR.2018.06.017.

- Stone AA, Schneider S, Smyth JM. 2023. Evaluation of pressing issues in ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 19(1):107–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-080921-083128.

- Stull SW, Smith KE, Vest NA, Effinger DP, Epstein DH. 2022. Potential value of the insights and lived experiences of addiction researchers with addiction. J Addict Med. 16(2):135–137. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000867.

- Swan JE, Aldridge A, Joseph V, Tucker JA, Witkiewitz K. 2021. Individual and community social determinants of health and recovery from alcohol use disorder three years following treatment. J Psychoact Drugs. 53(5):394–403. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2021.1986243.

- Todman LC, Diaz A. 2014. A public health approach to narrowing mental health disparities. Psychiatr Ann. 44(1):27–31. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20140108-05.

- Tomko C, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. 2022. Gaps and barriers in drug and alcohol treatment following implementation of the affordable care act. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 5:100115. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100115.

- Trangenstein PJ, Gray C, Rossheim ME, Sadler R, Jernigan DH. 2020. Alcohol outlet clusters and population disparities. J Urban Health. 97(1):123–136. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00372-2.

- Tucker JA, Buscemi J, Murphy JG, Reed DD, Vuchinich RE. 2023. Addictive behavior as molar behavioral allocation: distinguishing efficient and final causes in translational research and practice. Psychol Addict Behav. 37(1):1–12. doi: 10.1037/adb0000845.

- Tucker JA, Chandler SD, Witkiewitz K. 2020. Epidemiology of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res. 40(3):02. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.3.02.

- Tucker JA, Cheong JW, Chandler SD. 2021. Shifts in behavioral allocation patterns as a natural recovery mechanism: postresolution expenditure patterns. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 45(6):1304–1316. doi: 10.1111/acer.14620.

- Tucker JA, Roth DL, Vignolo MJ, Westfall AO. 2009. A behavioral economic reward index predicts drinking resolutions: moderation revisited and compared with other outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 77(2):219–228. doi: 10.1037/a0014968.

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. 2002. Environmental contexts surrounding resolution of drinking problems among problem drinkers with different help-seeking experiences. J Stud Alcohol. 63(3):334–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.334.

- Tucker JA, Witkiewitz K, editors. 2022. Dynamic pathways to recovery from alcohol use disorder: meaning and methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [accessed 2022 Mar 8]. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/dynamic-pathways-to-recovery-from-alcohol-use-disorder/2E1458402721727EDBB5A8171AA9F3A9.

- Venniro M, Panlilio LV, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. 2021. The protective effect of operant social reward on cocaine self-administration, choice, and relapse is dependent on delay and effort for the social reward. Neuropsychopharmacology. 46(13):2350–2357. doi: 10.1038/S41386-021-01148-6.

- Venniro M, Zhang M, Caprioli D, Hoots JK, Golden SA, Heins C, Morales M, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. 2018. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nat Neurosci. 21(11):1520–1529. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0246-6.

- Vilsaint CL, Hoffman LA, Kelly JF. 2019. Perceived discrimination in addiction recovery: assessing the prevalence, nature, and correlates using a novel measure in a U.S. national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 206:107667. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107667.

- Vilsaint CL, Kelly JF, Bergman BG, Groshkova T, Best D, White W. 2017. Development and validation of a Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10) for alcohol and drug use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 177:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.022.

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. 2016. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 374(4):363–371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1511480.

- Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA, Acuff SF, Reed DD, Buscemi J, Murphy JG. 2023. Matching, behavioral economics, and teleological behaviorism: final cause analysis of substance use and health behavior. J Exp Anal Behav. 119(1):240–258. doi: 10.1002/jeab.815.

- van der Wal JM, van Borkulo CD, Deserno MK, Breedvelt JJF, Lees M, Lokman JC, Borsboom D, Denys D, van Holst RJ, Smidt MP, et al. 2021. Advancing urban mental health research: from complexity science to actionable targets for intervention. Lancet Psychiatry. 8(11):991–1000. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00047-X.

- Wall TL, Luczak SE, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. 2016. Biology, genetics, and environment: underlying factors influencing alcohol metabolism. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 38(1):59–68.

- Wang D, Choi JK, Shin J. 2020. Long-term neighborhood effects on adolescent outcomes: mediated through adverse childhood experiences and parenting stress. J Youth Adolesc. 49(10):2160–2173. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01305-y.

- Wang S, Intille S, Ponnada A, Do B, Rothman A, Dunton G. 2022. Investigating microtemporal processes underlying health behavior adoption and maintenance: protocol for an intensive longitudinal observational study. JMIR Res Protoc. 11(7):e36666. doi: 10.2196/36666.

- White JJ, Mathews A, Henry MP, Moran MB, Page KR, Latkin CA, Tucker JD, Yang C. 2020. A crowdsourcing open contest to design pre-exposure prophylaxis promotion messages: protocol for an exploratory mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 9(1):e15590. doi: 10.2196/15590.

- Wiers RW, Verschure P. 2021. Curing the broken brain model of addiction: neurorehabilitation from a systems perspective. Addict Behav. 112:106602. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106602.

- Wiley ER, Stranges S, Gilliland JA, Anderson KK, Seabrook JA. 2022. Residential greenness and substance use among youth and young adults: associations with alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. Environ Res. 212(Pt A):113124. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2022.113124.

- Witkiewitz K, Litten RZ, Leggio L. 2019. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci Adv. 5(9):eaax4043. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax4043.

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. 2004. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. Am Psychol. 59(4):224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224.

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. 2007. Modeling the complexity of post-treatment drinking: it’s a rocky road to relapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 27(6):724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.002.

- Witkiewitz K, Montes KS, Schwebel FJ, Tucker JA. 2020. What is recovery? A narrative review of definitions of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res. 40(3):1. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.3.01.

- Witkiewitz K, Van Der Maas HLJJ, Hufford MR, Marlatt GA. 2007. Nonnormality and divergence in posttreatment alcohol use: reexamining the Project MATCH data “another way”. J Abnorm Psychol. 116(2):378–394. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.378.

- Witkiewitz K, Wilson AD, Pearson MR, Montes KS, Kirouac M, Roos CR, Hallgren KA, Maisto SA. 2019. Profiles of recovery from alcohol use disorder at three years following treatment: can the definition of recovery be extended to include high functioning heavy drinkers? Addiction. 114(1):69–80. doi: 10.1111/add.14403.

- World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [accessed 2022 Jun 17]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/?sequence=1.

- Wright AGC, Zimmermann J. 2019. Applied ambulatory assessment: integrating idiographic and nomothetic principles of measurement. Psychol Assess. 31(12):1467–1480. doi: 10.1037/pas0000685.

- Wycoff AM, Metrik J, Trull TJ. 2018. Affect and cannabis use in daily life: a review and recommendations for future research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 191:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.001.

- Xuan Z, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, Heeren T, Oussayef N, Naimi TS. 2015. The alcohol policy environment and policy subgroups as predictors of binge drinking measures among US adults. Am J Public Health. 105(4):816–822. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302112.