1. Introduction

Cephalosporins are a class of antibiotics commonly used to treat various bacterial infections. Warfarin, on the other hand, is an anticoagulant used to prevent blood clots in several cardiovascular indications. Interactions between cephalosporins and warfarin have been reported in the literature, where the addition of cephalosporins on top of ongoing warfarin therapy could potentiate the risk of bleeding or elevated international normalized ratio (INR), which indicates a higher risk of bleeding. This could be due to resultant hypoprothrombinemia, inhibition of p-glycoprotein, and alteration of the gastrointestinal flora by cephalosporins [Citation1]. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of this potential interaction, which could affect the safety of warfarin therapy. It is worth noting that while cephalosporins have been found to interact with warfarin, studies have not shown significant interactions between penicillins and warfarin [Citation1]. However, isolated cases of interactions have been reported with broad-spectrum penicillins; hence, caution should be exercised when prescribing these antibiotics to patients taking warfarin [Citation1].

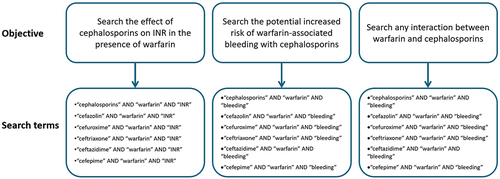

Literature research on the interaction between cephalosporins and warfarin was conducted on PubMed and Scopus databases from inception to 31 January 2024, which yielded seven clinical studies, one ex vivo study, and four case reports. shows the search terms used. We reviewed the available evidence on this issue, provided summaries of the studies, and made recommendations accordingly.

2. An overview of warfarin and the risk of bleeding

Warfarin functions as an anticoagulant by competitively inhibiting subunit 1 of the multiunit vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR) complex, leading to a depletion of functional vitamin K reserves and subsequently reducing the synthesis of active clotting factors. Its primary purpose is to prevent or mitigate the risk of serious conditions, such as stroke or deep venous thromboembolism [Citation1]. Although warfarin has been used very commonly, the clinical administration of warfarin presents a significant challenge as patients become more susceptible to major bleeding, especially when co-administered with medications that can modulate its metabolic pathways [Citation1].

3. An overview of cephalosporins and the risk of hemolysis

Cephalosporins are a subclass of the large β-lactam class of antibiotics. They are divided into several generations and differ in their coverage of bacterial pathogens, where some are broad-spectrum, while others are narrow-spectrum. They work by inhibiting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall by binding to penicillin-binding proteins in the bacterial cell wall, which interferes with the cross-linking of peptidoglycan, weakening the cell wall and leading to bacterial cell death [Citation2]. Common side effects of cephalosporins include gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Allergic reactions can also occur, ranging from mild rashes to severe allergic reactions like anaphylaxis.

Although cephalosporins are generally considered safe and effective, there have been rare cases of cephalosporin-induced hemolysis, which involves the destruction of red blood cells. Hemolysis can lead to anemia and other complications. Two case reports were identified in the literature that reported cephalosporin-induced hemolysis. The first case report was for a rare case of cefazolin-induced hemolytic anemia in an 80-year-old woman that developed 7 days after starting cefazolin (dose not specified) for the treatment of infective endocarditis due to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus [Citation3]. The authors stated that the underlying mechanism of this hemolytic process was unclear, but it may have involved immune-mediated mechanisms or nonimmune-mediated oxidant injury. The second case report was for a 76-year-old man who received 4 g of ceftriaxone for cholangitis. One-hour post dose, the patient deteriorated and was transferred to the intensive care unit. Lab work revealed signs of hemolysis, including decreased hemoglobin, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and disturbed coagulation parameters, indicating disseminated intravascular coagulation (increased INR to 3.31, undetectable fibrinogen, and thrombocytopenia with platelet count of 56,000/μL) [Citation4]. The authors concluded that this case presented a rare serious incidence of drug-induced hemolytic anemia that required correct diagnosis and immediate discontinuation of the culprit drug.

4. Potential mechanism of cephalosporin–warfarin interaction

The mechanism behind the interaction between cephalosporins and warfarin are not yet fully understood. However, it is assumed that the disruption of the intestinal flora that is necessary for the manufacturing of vitamin K may increase the risk of warfarin-induced excessive anticoagulation and bleeding. Some cephalosporins (such as cefazolin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, and cefepime) remain in the gut at high concentrations due to high biliary excretion, which could impact the organic production of vitamin K by normal gut flora [Citation2]. Additionally, it was evident in some rare cases that ceftriaxone could alter prothrombin time (PT) in patients with impaired vitamin K synthesis or low vitamin K stores as in the case of patients receiving warfarin [Citation2]. Furthermore, cephalosporins with an N-methylthiotetrazole (NMTT) side chain, such as second-generation cefamandole and third-generation cefoperazone, affect the action of warfarin when interacting with VKOR and cause a slight inhibition of the activity, leading to an increase in hypoprothrombinemia as observed in an ex vivo study [Citation5]. However, such interaction was not observed with cefazolin. It should be noted, however, that most of the cephalosporins that harbor the NMTT side chain are old and no longer used in clinical practice with the exception of cefotetan.

5. Clinical studies evaluating cephalosporin–warfarin interaction

A total of seven clinical studies and four case reports were identified in the literature search. includes a summary of the clinical studies. An old prospective randomized trial of 20 patients receiving warfarin compared the effect of adding cefamandole to that of cefazolin and vancomycin on changing PT, where PT was significantly increased in the cefamandole group by 64 ± 14% than in the cefazolin (51.1 ± 18%) and vancomycin (44.6 ± 19%) groups (P < 0.0001) [Citation6]. Another study evaluated the potential interaction of warfarin with antibiotics from different classes, including cephalosporins. In that case–control study, the authors reported that cephalosporins were associated with increased risk of hospitalization for bleeding in patients aged ≥65 years, where the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 2.45 and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was 1.52–3.95 in matched 75 cases and controls [Citation7]. Another retrospective study on patients receiving chronic warfarin therapy who presented with urinary tract infections and treated with ceftriaxone, a first-generation cephalosporin, penicillin, or ciprofloxacin, found that the addition of ceftriaxone (n = 27) was associated with increased INR to a more extent than the comparator antibiotics (n = 93); though, no bleeding was reported [Citation8]. A study by Teklay, et al. evaluated the level of interaction of various drugs with warfarin and the associated risk of bleeding. The study included 35 patients who received cephalosporins. While ceftriaxone was associated with moderate interaction with warfarin, the remaining cephalosporins were associated with major interaction. Nevertheless, the odds of bleeding in case of major interaction did not reach statistical significance (aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.60–3.80; p = 0.39) [Citation9]. A retrospective cohort study compared the effect of various β-lactams, including cephalosporins to that of fluoroquinolone antibiotics on PT-INR values in warfarin users, which reported a significant increase in INR values from baseline in both groups (P < 0.01). However, the effect was more pronounced with fluoroquinolones (change was 0.23 with intravenous β-lactams and 0.06 with oral β-lactams vs. 0.4 with intravenous fluoroquinolones and 0.17 with oral fluoroquinolones) [Citation10]. One study analyzed a Japanese health insurance claims database and found that both cephalosporins with and without the NMTT side chain enhanced the effects of warfarin, potentially increasing bleeding risk [Citation11].

Table 1. Summary of clinical studies evaluating cephalosporin–warfarin interaction.

The four case reports were all of old patients (≥65 years) who have been on warfarin for various indications [Citation12–15]. One case involved ceftriaxone, two involved ceftaroline, and one involved cephalexin. All the cases developed INR elevation after the addition of the cephalosporin. The details of the case reports are shown in .

Table 2. Summary of case reports involving cephalosporin–warfarin interaction.

6. Expert opinion

The current available evidence on the interaction between cephalosporins and warfarin indicates that this combination may pose an increased risk of INR elevation with or without consequent bleeding. Nevertheless, the number of patients assessed in the currently available clinical studies is fairly small (including case reports of single cases), especially that some studies evaluated numerous other drugs or other β-lactams resulting in even a smaller proportion of patients who received cephalosporins. Moreover, some studies did not have a control group, such as the study by Yagi, et al. [Citation10]. Therefore, investigators are encouraged to study this interaction in larger cohorts to confirm the findings of the previous smaller studies. Additionally, no recent studies or case reports/series have been found in the literature as most studies were old. Nonetheless, since this potential interaction is serious, caution should still be exercised by clinicians who initiate cephalosporins for patients on chronic warfarin therapy. This should involve close monitoring of INR and adjusting warfarin dose accordingly. Additionally, discontinuing antibiotic therapy once the patient achieves clinical stability or if antibiotic therapy is deemed unnecessary is also important to eliminate the risk of this interaction and as an antibiotic stewardship intervention to avoid prolonged unnecessary courses of antibiotics; thus, reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance development. Large clinical studies are needed to explore this interaction and potentially explain the mechanism behind it.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Vega AJ, Smith C, Matejowsky HG, et al. Warfarin and antibiotics: drug interactions and clinical considerations. Life (Basel). 2023 Jul 30;13(8). doi: 10.3390/life13081661

- Product information: ROCEPHIN®, ceftriaxone sodium for injection. Nutley (NJ): Roche Laboratories Inc; 2018.

- Mause E, Selim M, Velagapudi M. Cefazolin-induced hemolytic anemia: a case report and systematic review of literature. Eur J Med Res. 2021 Nov 24;26(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00604-9

- Leicht HB, Weinig E, Mayer B, et al. Ceftriaxone-induced hemolytic anemia with severe renal failure: a case report and review of literature. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018 Oct 25;19(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s40360-018-0257-7

- Kawamoto K, Touchi A, Sugeno K, et al. In vitro effect of beta-lactam antibiotics and N-methyltetrazolethiol on microsomal vitamin K epoxide reductase in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1988 Jun;47(2):169–178. doi: 10.1016/S0021-5198(19)43231-9

- Angaran DM, Dias VC, Arom KV, et al. The comparative influence of prophylactic antibiotics on the prothrombin response to warfarin in the postoperative prosthetic cardiac valve patient. Cefamandole, cefazolin, vancomycin. Ann Surg. 1987 Aug;206(2):155–161. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198708000-00007

- Baillargeon J, Holmes HM, Lin YL, et al. Concurrent use of warfarin and antibiotics and the risk of bleeding in older adults. Am J Med. 2012 Feb;125(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.014

- Saum LM, Balmat RP. Ceftriaxone potentiates warfarin activity greater than other antibiotics in the treatment of urinary tract infections. J Pharm Pract. 2016 Apr;29(2):121–124. doi: 10.1177/0897190014544798

- Teklay G, Shiferaw N, Legesse B, et al. Drug-drug interactions and risk of bleeding among inpatients on warfarin therapy: a prospective observational study. Thromb J. 2014;12(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-12-20

- Yagi T, Naito T, Kato A, et al. Association between the prothrombin time-international normalized ratio and concomitant use of antibiotics in warfarin users: focus on type of antibiotic and susceptibility of bacteroides fragilis to antibiotics. Ann Pharmacother. 2021 Feb;55(2):157–164. doi: 10.1177/1060028020940728

- Imai S, Kadomura S, Momo K, et al. Comparison of interactions between warfarin and cephalosporins with and without the N-methyl-thio-tetrazole side chain. J Infect Chemother. 2020 Nov;26(11):1224–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.07.014

- Clark TR, Burns S. Elevated international normalized ratio values associated with concomitant use of warfarin and ceftriaxone. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011 Sep 1;68(17):1603–1605. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100681

- Bohm NM, Crosby B. Hemarthrosis in a patient on warfarin receiving ceftaroline: a case report and brief review of cephalosporin interactions with warfarin. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 Jul;46(7–8):e19. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q771

- Farhat NM, Hutchinson LS, Peters M. Elevated international normalized ratio values in a patient receiving warfarin and ceftaroline. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016 Jan 15;73(2):56–59. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140897

- Chartier AR, Hillert CJ, Gill H, et al. Acquired factor V inhibitor after antibiotic therapy: a clinical case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2020 Jul 30;12(7):e9481. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9481