ABSTRACT

While sustainability topics are gaining prominence in the communication strategies of fast-fashion brands, consumers remain sceptical and suspicious of the ambiguous and often misleading sustainable brand content. The purpose of this study is to analyse the perception of greenwashing in fast-fashion brands' sustainable communication and to identify its link to consumers' sustainable behaviour and attitudes. An analysis was conducted on five fast-fashion leading brands, based on a non-experimental cross-sectional analytical design and using an online survey. Research results show that consumers perceive greenwashing in the communication of all fast-fashion brands. Furthermore, the perception of greenwashing is higher when it is associated with the search for information on sustainable fashion, as well as the purchase of sustainable fashion. The study also concludes that the perception of greenwashing increases when fast fashion brands carry out advertising campaigns or disseminate their sustainability content through influencers or on their websites.

1. Introduction

In recent years, consumers have become more concerned and aware of the social and environmental impact of brands (Johnstone & Tan, Citation2015; Yoon & Park, Citation2021). According to the Future Consumer Index Report (Samu & Vello, Citation2022), 63% of consumers prioritise the social impact of the brands they buy, and 51% would stop purchasing from companies with questionable social or environmental performance.

The negative impact of the fashion industry on the environment caused by the excessive use of energy and natural resources in the production process, the use of harmful chemicals or the amount of generated waste, among others (Colucci & Vecchi, Citation2021; Mukendi, Davies, Glozer, & McDonagh, Citation2020; Pedersen & Andersen, Citation2015) is of high concern for consumers. Addressing sustainability challenges facing the fashion industry, a growing number of fashion brands have been engaged in communication strategies claiming their environmental credentials and commitment to sustainability. However, the increase in misleading and ambiguous communication narratives featuring sustainable values of companies has led to a certain mistrust and scepticism among consumers regarding the real reasons for fashion brands to claim their sustainability commitment. As a consequence, the phenomenon of ‘greenwashing’ was identified and conceptualised in the last decade (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Aji & Sutikno, Citation2015).

This research arises from the disjunction between the efforts of brands to convey their sustainability initiatives and consumers’ perception that such communication constitutes greenwashing. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to study consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing within the sustainability communication strategies of fast-fashion brands. The main research questions are the following:

RQ1. Do consumers perceive greenwashing in sustainable initiatives’ communication by fast-fashion brands?

RQ2. Do consumers’ knowledge of sustainability principles and their consumption of sustainable fashion moderate the perception of greenwashing in fast-fashion brand communication?

RQ3. Does the perception of greenwashing in fast-fashion brands get influenced by specific communication formats, such as advertising, communication by influencers, or corporate websites?

1.1. Attitudes and behaviours towards sustainable fashion

There are multiple terms for sustainable fashion, including eco-fashion, ethical fashion, green fashion, conscious fashion, and responsible fashion, among others. This plethora of terms has led to some confusion among consumers about what a sustainable fashion company really is (Beard, Citation2008; Thomas, Citation2008). Thus, the term ‘sustainability’ has become an overused and very confusing concept for the consumers.

At the same time, consumers expect socially and environmentally responsible strategies from companies and governments, yet they often lack personal commitment to responsible consumption (Ha-Brookshire & Norum, Citation2011; Bianchi & Gonzalez, Citation2021; Blazquez, Henniger, Alexander, & Franquesa, Citation2020; Jacobs, Petersen, Horisch, & Battenfeld, Citation2018; McNeill & Moore, Citation2015; Chan & Wong, Citation2012). This paradox has been defined as the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’, i.e. when a positive attitude does not translate into subsequent action (Wiederhold & Martinez, Citation2018; Rausch & Kopplin, Citation2021), which in the fashion industry has been described as ‘the fashion paradox’ (Black, Citation2008; McNeill & Moore, Citation2015).

Consumers have low knowledge of sustainable fashion and are not able to differentiate a sustainable brand from a non-sustainable one (Blas Riesgo, Lavanga, & Codina, Citation2023; Kaner & Baruh, Citation2022). Other studies have shown that having a positive attitude towards sustainability and greater knowledge about the environmental impact of the fashion industry does not affect purchasing intentions for sustainable fashion (Kozar & Connell, Citation2013; Achabou, Dekhili, & Codini, Citation2020). In fact, Goworek, Hiller, Fisher, Cooper, and Woodward (Citation2013) argue that consumers’ sustainable behaviour relies more on habits than on knowledge about companies’ sustainable practices.

In particular, the main barrier associated with the purchase of sustainable fashion products is consumers’ perception of their higher price compared to other fashion products (Bianchi & Gonzalez, Citation2021; Brandão & Costa, Citation2021; Diddi, Yan, Bloodhart, Bajtelsmit, & McShane, Citation2019; Lundblad & Davies, Citation2016; Ha-Brookshire & Norum, Citation2011). A further deterrent is the perception that such products are less ‘fashionable’ (Blazquez et al., Citation2020; Diddi et al., Citation2019; Min Kong & Ko, Citation2017) and not stylish enough (Connell, Citation2011). In this regard, Ritch and Schroder (Citation2012) found that consumers are not willing to give up style or comfort to buy sustainable fashion.

Furthermore, Blas Riesgo et al. (Citation2023) found that in addition to the perception of higher price, lower quality and limited availability, another important barrier is the lack of trust in companies and their sustainability claims, as personal ethical values related to sustainability are more important in the intention to purchase sustainable fashion. The authors argue also that higher sustainability awareness leads to lower purchase of sustainable fashion products. Consumers opt for second-hand products or renting rather than buying new sustainable items.

1.2. The phenomenon of greenwashing

The phenomenon of greenwashing was first identified in 1986 by environmentalist Jay Westerveld as a deceptive communication practice by companies to sell their sustainability to their audiences (Orange & Cohen, Citation2010). Becker-Olsen and Potucek (Citation2013) understand greenwashing as ‘the practice of falsely promoting an organisation’s environmental efforts or spending more resources to promote the organisation as green than are spent to engage in environmentally sound practices’. Nemes et al. (Citation2022) also define it as ‘an umbrella term for a variety of misleading communications and practices that intentionally or not, induce false positive perceptions of an organisation’s environmental performance’. Along the same lines, we find definitions by Delmas and Burbano (Citation2011), Baum (Citation2012), Lyon and Montgomery (Citation2015) and Tateishi (Citation2018).

De Freitas, Sobral, Ribeiro, and Soares (Citation2020) point out two different ways of greenwashing: One at the ‘product/service level’ where textual arguments that explicitly or implicitly refer to the ecological advantages of a product or service are used to create a misleading environmental claim and another at the ‘execution level’ when elements (images or sounds) that evoke nature are used. Vague and ambiguous communication about a company’s sustainability is therefore a strategy that causes confusion, mistrust and disloyalty among consumers (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Aji & Sutikno, Citation2015). As Munir and Mohan (Citation2022, p. 5) point out, it is ‘an implicit form of deception as consumers wrongly interpret the meaning and draw positive inferences about the product attribute’.

1.3. Greenwashing in the fast-fashion industry

Bick, Halsey, and Ekenga (Citation2018) define fast fashion as ‘readily available, inexpensively made fashion of today’. According to Munir and Mohan (Citation2022), the fast fashion business model is based on the concept of ‘fashion obsolescence’, where companies spread a ‘throwaway’ culture (Cooper, Citation2005) which negates any pro-environmental initiative. This business model clashes with one of the objectives set by the European Commission (according to the European Green Pact, Citation2022) which states that, by 2030, clothing should be ‘more durable, repairable, reusable and recyclable in order to combat fast fashion, textile waste and the destruction of unsold textile products’.

In recent years numerous fast-fashion companies have launched sustainable communication campaigns centred on basic claims like ‘using organic cotton’, ‘reusing or second-hand’ (e.g. Zara Pre-Owned), and creating eco-friendly sub-brands (such as Zara's Join Life or H&M's Conscious), to showcase their commitment to sustainability and the environment.

Some authors have emphasised the positive effect of sustainable communication on websites and using hashtags (Li & Leonas, Citation2022) as well as leveraging celebrities and influencers to promote sustainable actions of brands (Moorhouse & Moorhouse, Citation2017). Han, Henninger, Apeagyei, and Tyler (Citation2017) stress the significance of using persuasive narratives along with data and facts to enhance the credibility of sustainability initiatives. Szabo and Webster (Citation2021) argue that these communication efforts are specifically focused on ecologically conscious consumers.

Despite these efforts, many consumers remain sceptical and distrustful of fast fashion companies’ marketing communication. From 2019 to 2022, the volume of greenwashing-related news stories in traditional media and social networks (especially on Twitter and LinkedIn) has been doubling every year, with the fashion industry being one of the most scrutinised by consumers (Onclusive, Citation2023). In this regard, The State of Fashion Citation2023 report by Business of Fashion (BOF) and McKinsey describes greenwashing as one of the most critical issues facing the fashion industry today and, in particular, fast fashion companies. Research by Delmas and Burbano (Citation2011) highlights the growing complexity of the greenwashing practice, with misleading environmental claims on the corporate level and actions aimed at enhancing environmental values of products or services. De Jong, Huluba, and Beldad (Citation2020) argue that greenwashing negatively affects corporate reputation, product and service perception, and financial performance.

To address this issue, the European Commission in March Citation2023 launched the third package of measures (Directive on Green Claims) to prevent greenwashing and misleading environmental claims. From now on when a company makes a claim using sustainability as an argument, it must be substantiated and verified by independent and accredited companies.

In this context, it is worth asking whether, despite the efforts made by some fast fashion brands to develop and communicate sustainable initiatives, consumers perceive greenwashing and whether this perception could be explained by certain behaviours and attitudes related to sustainability and media consumption.

Some specific objectives are also identified for this study:

To assess the perception of greenwashing in Spanish fast fashion brands (Zara, Bershka, Mango, Stradivarius and Springfield)

To explore consumer engagement with sustainable fashion content and sustainable fashion purchases.

To investigate the mediating effect of sustainable fashion consumption and consumer attitudes towards sustainability on their perception of greenwashing.

To propose an explanatory and predictive model of greenwashing perception in fast fashion brands based on preceding behaviours and attitudes.

2. Methodology

The research carried out was descriptive and causal, based on a non-experimental, cross-sectional, analytical design. An online survey was conducted among 1001 individuals in Spain. The distribution of the sample corresponds to the structure of the population by gender (51.1% women, 48.8% men and 0.1% do not state their gender), age (35.5% up to 34 years old, 34.7% between 35–54 years old and 32.8% from 55 years old onwards) and their place of residence (INE Base, Citation2022). This sample size corresponds to an indicative error, assuming simple random sampling, of ±3.15% for a confidence level of 95.5% (P = Q = 50% and 2 sigma).

An ad hoc structured questionnaire was used, whose variables and items were established based on the greenwashing concept of Becker-Olsen and Potucek (Citation2013) and Nemes et al. (Citation2022), the communication channels and media used to disseminate information on sustainable fashion identified by Han et al. (Citation2017), Vehmas, Raudaskoski, Heikkilä, Harlin, and Mensonen (Citation2018) and Díaz-Soloaga (Citation2021), and following the results of the studies by Wiederhold and Martinez (Citation2018), Blazquez et al. (Citation2020), Bianchi and Gonzalez (Citation2021) and Blas Riesgo et al. (Citation2023) on consumption behaviour and attitudes towards sustainable fashion (see ).

Table 1. Elements under study and variables used.

The selection process of survey participants was randomised in accordance with theoretical quotas of sex, age and place of residence based on a panel of consumers in Spain. The collecting of information was conducted in November 2022 by the company Grupo Análisis e Investigación. The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using SPSS v28. Starting with the basic univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics, the Chi-square test and binary logistic regression analysis, among others, were applied.

Five Spanish fast fashion brands with the largest market share in Spain were included in the analysis: Zara, Bershka, Mango, Stradivarius and Springfield (see ). All five brands belong to one of the three leading Spanish fashion holdings: Inditex (Zara, Bershka and Stradivarius), Punto Fa-Mango (Mango) and Tendam Retail Group (Springfield). The brand selection criteria were based on its leading market position within each holding, national sales volume and number of stores.

Table 2. Fashion brands included in the study.

While the study only covers the Spanish market, the global relevance of the Spanish fast-fashion industry makes the results generalisable to other markets. Other limitations of the study is its quantitative nature and the exclusive focus on the perception of greenwashing practices by consumers. Conducting qualitative research could enhance key findings with deeper consumer insights. Additionally, exploring the perspective on greenwashing of communication managers in the fast-fashion industry would be valuable for future research.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Perception of greenwashing in Spanish fast fashion brands

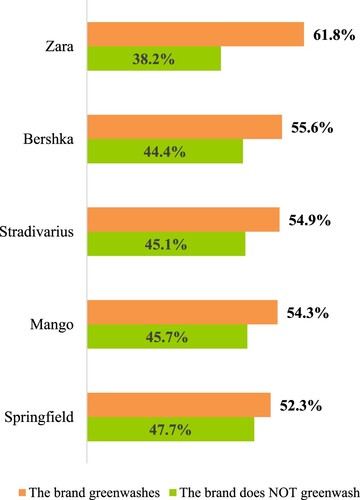

As shown in , the majority of respondents perceive the existence of greenwashing in all five brands included in the analysis: Zara, Bershka, Stradivarius, Mango and Springfield, with no significant differences by gender, age, occupation or level of education.

3.2. Attitudes and behaviours towards sustainable fashion associated with the perception of greenwashing

As shown in , the search for information on sustainable fashion is significantly associated with the perception of the existence of greenwashing in all the fashion brands considered. Furthermore, it has been observed (Chi-Square test) that such perception does not present significant differences regarding the use of different communication channels to access information on sustainable fashion, except for the Bershka and Springfield brands.

Table 3. Association between the perception of greenwashing in fashion brands and consumption of sustainable fashion content – Chi-Square test.

In the case of Bershka, the perception of not greenwashing is significantly associated with not using the brands’ profiles on Instagram (Sig. x2 = 0.01) and TikTok (Sig. x2 = 0.014), and not viewing advertisements in online and offline media (Sig. x2 = 0.041) and celebrity trending media (Sig. x2 = 0.023). As for Springfield, the perception of greenwashing is significantly associated with the consumption of reports, interviews and monographic documentaries to access sustainable fashion content (Sig. x2 = 0.008).

With respect to consumption of sustainable fashion products, reveals a significant association between having previously purchased a sustainable fashion product and perceiving the existence of greenwashing across all examined brands. This finding fortifies the initial proposition positing a correlation between behaviours and perceptions. Additionally, the absence of such perception is linked to the lack of advertising influence from the brands in the decision-making process for sustainable fashion purchases. This observation leads us to contemplate the possibility that fashion brands’ advertising campaigns may exert an adverse impact on audiences, fostering the perception that said brands engage in greenwashing practices.

Table 4. Association between the perception of greenwashing in fashion brands and consumption of sustainable fashion products – Chi-Square test.

Conversely, there were no significant distinctions observed in the perception of greenwashing across the analysed brands concerning the influence of recommendations from influencers or celebrities on the purchase of sustainable fashion products.

Regarding respondents’ attitudes towards the sustainability policies communicated by fashion companies, illustrates that agreement with almost all of the opinions (except for ‘I am not interested in the sustainability information provided by fashion brands’) is very significantly associated with the perception of greenwashing in all of the brands considered. These opinions mainly reflect negative or sceptical attitudes towards the sustainability policies that fashion companies convey in their communications, and which result in a negative perception of the brands they market and by answering in the affirmative the consumer considers that the brands are trying to greenwash their image through these messages. Thus, it seems logical that brands need to rethink the content or style of sustainability messages they communicate in order to convey credibility to their audiences.

Table 5. Association between perceptions of greenwashing in fashion brands and attitudes towards sustainability policies of fashion companies – Chi-Square test.

3.3. Explanatory and predictive models of the probability of perceiving greenwashing in Spanish fast-fashion brands

The first model () establishes that the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Zara brand increases when information on sustainable fashion is accessed through the brands’ websites and when recommendations from influencers or celebrities influence the decision to purchase sustainable fashion. Conversely, this probability decreases when TikTok is not used to access sustainable fashion content and when brands’ advertising campaigns do not influence the sustainable fashion purchase decision. The indicators of model performance are as follows: the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Chi-square = 2.563; p = 0.767), the percentage of cases that the model is able to predict correctly (70%) and the area under the COR curve (0.686).

Table 6. Logistic regression model on the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Zara brand.

The second model (), relating to the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Bershka brand, indicates that this probability increases when information on sustainable fashion is accessed through the brands’ websites and when influencers’ or celebrities’ recommendations influence the decision to buy sustainable fashion. Conversely, the likelihood decreases when Instagram is not used to access sustainable fashion content and when brands’ advertising campaigns do not influence the sustainable fashion purchasing decision. The indicators of model performance are as follows: the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Chi-square = 2.956; p = 0.814), the percentage of cases that the model is able to predict correctly (69.7%) and the area under the COR curve (0.701).

Table 7. Logistic regression model on the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Bershka brand.

The third model () determines that the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Stradivarius brand increases when information on sustainable fashion is accessed through the brands’ websites and decreases when the brands’ advertising campaigns do not influence the decision to purchase sustainable fashion. The indicators of model performance are as follows: the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Chi-square = 0.090; p = 0.764), the percentage of cases the model is able to predict correctly (64.4%) and the area under the COR curve (0.619).

Table 8. Logistic regression model on the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Stradivarius brand.

The fourth model () shows that the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Mango brand increases when information on sustainable fashion is sought and when recommendations from influencers or celebrities influence the decision to purchase sustainable fashion. Conversely, the likelihood of greenwashing decreases when videos on the brands’ YouTube channels are not used to access sustainable fashion content and when the brands’ advertising campaigns do not influence the sustainable fashion purchase decision. The indicators of model performance are as follows: the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Chi-square = 2.381; p = 0.882), the percentage of cases the model is able to predict correctly (69.3%) and the area under the COR curve (0.677).

Table 9. Logistic regression model on the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Mango brand.

The last model proposed (), concerning the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the brand Springfield, reveals that such perception is heightened when individuals actively seek information on sustainable fashion and utilise specialised features such as reports, interviews, or monographic documentaries for this purpose. Conversely, the perception diminishes when brand advertising campaigns do not exert an influence on the decision-making process for sustainable fashion purchases. The indicators of model performance are as follows: the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (Chi-square = 9.049; p = 0.107), the percentage of cases correctly predicted by the model (69.7%), and the area under the COR curve (0.680).

Table 10. Logistic regression model on the probability of perceiving greenwashing in the Springfield brand.

In conclusion, based on the proposed models, the variables with the greatest capacity to explain and predict the perception of greenwashing in the communication of Spanish fast fashion brands are as follows:

The influence of brand advertising campaigns on the decision-making process for sustainable fashion purchases.

The access to brand websites to search information on sustainable fashion.

The impact of influencers’ or celebrities’ recommendations on the decision to purchase sustainable fashion products.

The active search for information on sustainable fashion.

Consequently, we can assert:

When there is no influence of brand advertising campaigns on the decisión-making process for sustainable fashion products purchases, consumers’ likelihood to perceive greenwashing in fast fashion brands decreases.

When consumers access information on sustainable fashion on brands’ websites, the likelihood to perceive greenwashing increases.

When there is an impact of influencers’ or celebrities’ recommendations on the decision to purchase sustainable products, consumers’ likelihood to perceive greenwashing increases.

When there is search for information on sustainable fashion, consumers’ likelihood to perceive greenwashing increases.

4. Conclusions and discussion

Greenwashing poses a significant challenge for many brands within the fast-fashion industry. While brands strive to communicate their sustainability initiatives, many consumers perceive such communication as greenwashing, resulting in negative impact on brands’ reputation. This paper provides insights into the likelihood of greenwashing perception within the fast-fashion industry based on various attitudinal and behavioral variables.

The analysis of five leading fast-fashion Spanish brands reveals that consumers perceive sustainability-related messages as greenwashing, aimed at improving brand image. Previous studies support the notion that fast-fashion brands’ characteristics (low price, high availability and high number of collections per year) are contradictory to those of sustainable fashion (Bianchi & Gonzalez, Citation2021; Brandão & Costa, Citation2021; Diddi et al., Citation2019; Lundblad & Davies, Citation2016; Ha-Brookshire & Norum, Citation2011; Blazquez et al., Citation2020; Min Kong & Ko, Citation2017; Blas Riesgo et al., Citation2023).

Fast-fashion brands must adapt their communication policies and strategies to address the increasing consumer demand and concern for sustainability-related business practices. Kaner & Baruh, Citation2022 pointed out that ‘increasing sustainability knowledge, building credible and accessible communication strategies, and segmenting this according to the needs and demands of the consumer constitute a valuable role in motivating sustainable behaviour’ (p. 392). Moreover, this information would be useful to design new strategies for sustainable fashion communication in online and offline contexts.

The main contribution of this study is the link that it establishes between behavioural and attitudinal variables in sustainability and the perception of greenwashing in fast-fashion brand communication, explaining the likelihood of this perception based on these variables.

It shows that buying and seeking information about sustainable fashion and having negative attitudes towards companies’ sustainability policies are clearly related to perceiving the sustainable communication of fast-fashion brands as greenwashing. This suggests that consumers who are more concerned and aware of sustainability are more sensitive to perceiving the bad practices of brands seeking to greenwash their image with sustainability-based messages and are also more sceptical of these messages.

It has also been corroborated that when consumers search for information on sustainable fashion on brand websites they are more likely to perceive greenwashing in fast fashion brands.

In this regard, fast-fashion brands in their commercial and corporate communications should emphasise arguments and data that guarantee the veracity and results of their sustainability policies, as Evans and Peirson-Smith (Citation2018), Han et al. (Citation2017) and Vehmas et al. (Citation2018) have already pointed out. And they should especially do so in terms of communications on their websites and social media, given the importance of these channels for communicating sustainability initiatives (Da Giau et al., Citation2016). This also reinforces the European Commission's call, within the European Green Pact, to combat greenwashing and avoid misleading environmental claims.

Regarding the explanatory relationship between the influence of influencers’ recommendations on the decision to purchase sustainable fashion and the likelihood that greenwashing is perceived to exist in fast fashion brands, it would be interesting to delve deeper into the reasons for this. Moorhouse and Moorhouse (Citation2017) have already pointed out the importance of influencers in communicating sustainability values associated with a brand, but one could question the credibility that influencers can have when communicating sustainability messages, as well as the type of content that is disseminated.

It should also be noted that for those consumers who claim that advertising does not influence them when buying sustainable fashion, the likelihood that they perceive greenwashing in fast fashion brands decreases. In this respect, it can be assumed that they are consumers who are indifferent to advertising and whose purchasing behaviour is mainly based on ethical and personal convictions, as pointed out by Blas Riesgo et al. (Citation2023), or on responsible consumption habits (Goworek et al., Citation2013), and not so much on having greater knowledge of the issue through the commercial messages of brands.

This lack of knowledge and widespread confusion about what a sustainable fashion company is (Beard, Citation2008; Thomas, Citation2008) constitute a challenge for fast-fashion companies to educate consumers about their sustainability policies. In this regard, these brands should advance their sustainability practices beyond what are considered to be small and inefficient gestures that are often perceived as greenwashing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achabou, M. A., Dekhili, S., & Codini, A. P. (2020). Consumer preferences towards animal-friendly fashion products: An application to the Italian market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(6), 661–673.

- Aji, H. M., & Sutikno, B. (2015). The extended consequence of greenwashing: Perceived consumer skepticism. International Journal of Business and Information, 10(4), 433.

- Baum, L. M. (2012). It's Not easy being green … Or Is It? A content analysis of environmental claims in magazine advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom. Environmental Communication, 6(4), 423–440.

- Beard, N. D. (2008). The branding of ethical fashion and the consumer: A luxury niche or mass-market reality? Fashion Theory, 12(4), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174108X346931

- Becker-Olsen, K., & Potucek, S. G. (2013). Greenwashing. In S. O. Idowu, N. Capaldi, L. Zu, & A. D. Gupta (Eds.), Encyclopedia of corporate social responsibility (pp. 1318–1323). Berlin: Springer.

- Bianchi, C., & Gonzalez, M. (2021). Exploring sustainable fashion consumption among eco-conscious women in Chile. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 31(4), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2021.1903529

- Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 19(92), 1–14.

- Black, S. (2008). Eco chic: The fashion paradox. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Blas Riesgo, S., Lavanga, M., & Codina, M. (2023). Drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption in Spain: A comparison between sustainable and non-sustainable consumers. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2022.2089239

- Blazquez, M., Henniger, C. E., Alexander, B., & Franquesa, C. (2020). Consumers’ knowledge and intentions towards sustainability: A Spanish Fashion perspective. Fashion Practice, 12(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2019.1669326

- Brandão, A., & Costa, A. G. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behaviour to understand the effects of barriers towards sustainable fashion consumption. European Business Review, 33(5), 742–774. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2020-0306

- Business of Fashion (BOF) & McKinsey. (2023, March 20). The state of fashion 2023. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-fashion?stcr=FC146E33721A4327BD29AD236495ACD2&cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=d63fb8de9c994f9ba85ed4fff6765ad4&hctky=13261411&hdpid=c699dabc-62a1-4f26-aabf-f599dda7f98f

- Chan, T. Y., & Wong, C. W. (2012). Heterotopian space and the utopics of ethical and green consumption. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3-4), 494–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2012.668922

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

- Colucci, M., & Vecchi, A. (2021). Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30, 856–873. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2658

- Connell, K. Y. H. (2011). Exploring consumers' perceptions of eco-conscious apparel acquisition behaviors. Social Responsibility Journal, 7, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111111114549

- Cooper, T. (2005). Slower consumption reflections on product life spans and the “throwaway society”. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9(1-2), 51–67.

- Da Giau, A., Macchion, L., Caniato, F., Caridi, M., Danese, P., Rinaldi, R., & Vinelli, A. (2016). Sustainability practices and web-based communication. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0061

- De Freitas, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & Soares, G. R. (2020). Relationship between agricultural pesticides and the diet of riparian spiders in the field. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1), 1–12.

- De Jong, M. D. T., Huluba, G., & Beldad, A. D. (2020). Different shades of greenwashing: Consumers’ reactions to environmental lies, half-lies, and organizations taking credit for following legal obligations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 34(1), 38–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651919874105

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54, 64–87.

- Díaz-Soloaga, P. (2021). Communication in the fashion industry: Sustainability focus. In Firms in the fashion industry: Sustainability, luxury and communication in an international context (pp. 117–139). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Diddi, S., Yan, R. N., Bloodhart, B., Bajtelsmit, V., & McShane, K. (2019). Exploring young adult consumers’ sustainable clothing consumption intention-behavior gap: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 18, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2019.02.009

- European Commission. (2022, March 30). EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from www.eurlex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0141&from=EN

- European Commission. (2023, March 27). Consumer protection: Enabling sustainable choices and ending greenwashing. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1692

- Evans, S., & Peirson-Smith, A. (2018). The sustainability word challenge: Exploring consumer interpretations of frequently used words to promote sustainable fashion brand behaviors and imagery. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(2), 252–269.

- Goworek, H., Hiller, A., Fisher, T., Cooper, T., & Woodward, S. (2013). Consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable fashion: Clothing usage and disposal. In Sustainability in fashion and textiles: Values, design, production, and consumption (pp. 376–392). London: Routledge.

- Ha-Brookshire, J. E., & Norum, P. S. (2011). Willingness to pay for socially responsible products: Case of cotton apparel. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(5), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111149992

- Han, S. L. C., Henninger, C. E., Apeagyei, P., & Tyler, D. (2017). Determining effective sustainable fashion communication strategies. In Sustainability in fashion (pp. 127–149). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE Base. (2022). Población residente por fecha, sexo y edad. Retrieved from https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=9681&L=0

- Jacobs, K., Petersen, L., Horisch, J., & Battenfeld, D. (2018). Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1155–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.320

- Johnstone, M. L., & Tan, L. P. (2015). An exploration of environmentally-conscious consumers and the reasons why they do not buy green products. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(5), 804–825. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2013-0159

- Kaner, G., & Baruh, L. (2022). How to speak ‘sustainable fashion’: four consumer personas and five criteria for sustainable fashion communication. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 15(3), 385–393.

- Kozar, J. M., & Connell, K. Y. H. (2013). Socially and environmentally responsible apparel consumption: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Social Responsibility Journal, 9(2), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-09-2011-0076

- Li, J., & Leonas, K. K. (2022). The impact of communication on consumer knowledge of environmentally sustainable apparel. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 26(4), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-02-2021-0034

- Lundblad, L., & Davies, I. A. (2016). The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1559

- Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and End of greenwash. Organization & Environment, 28(2), 223–249.

- McNeill, L., & Moore, R. (2015). Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12169

- Min Kong, H., & Ko, E. (2017). Why do consumers choose sustainable fashion? A cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 8(3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2017.1336458

- Moorhouse, D., & Moorhouse, D. (2017). Sustainable design: Circular economy in fashion and textiles. The Design Journal, 20(1), S1948–S1959. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352713

- Mukendi, A., Davies, I., Glozer, S., & McDonagh, P. (2020). Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. European Journal of Marketing, 54(11), 2873–2909. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0132

- Munir, S., & Mohan, V. (2022). Consumer perceptions of greenwashing: Lessons learned from the fashion sector in the UAE. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 1–44.

- Nemes, N., Scanlan, S. J., Smith, P., Smith, T., Aronczyk, M., Hill, S., … Stabinsky, D. (2022). An integrated framework to assess greenwashing. Sustainability, 14(8), 4431.

- Onclusive. (2023). Construir la reputación de marca evitando el riesgo greenwashing. Retrieved from https://onclusive.com/es/recursos/informes/construir-la-reputacion-de-marca-evitando-el-riesgo-de-greenwashing/

- Orange, E., & Cohen, A. M. (2010). From eco-friendly to eco-intelligent. The Futurist, 44(5), 28–32.

- Pedersen, E. R., & Andersen, K. R. (2015). Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: A global expert study on sustainable fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(3), 315–327.

- Rausch, T. M., & Kopplin, S. F. (2021). Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123882

- Ritch, E. L., & Schroder, M. J. (2012). Accessing and affording sustainability: The experience of fashion consumption within young families. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01088.x

- Samu, D., & Vello, J. (2022). Future consumer index. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/es_es/el-consumidor-una-perspectiva-global/future-consumer-index-deconstruyendo-al-consumidor-post-covid-y-su-apuesta-por-el-consumo-sostenible

- Szabo, S., & Webster, J. (2021). Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 171, 719–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

- Tateishi, E. (2018). Craving gains and claiming “green” by cutting greens? An exploratory analysis of greenfield housing developments in Iskandar Malaysia. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(3), 370–393.

- Thomas, S. (2008). From “green blur” to ecofashion: Fashioning an Eco-lexicon. Fashion Theory, 12(4), 525–539. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174108X346977

- Vehmas, K., Raudaskoski, A., Heikkilä, P., Harlin, A., & Mensonen, A. (2018). Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(3), 286–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-08-2017-0079

- Wiederhold, M., & Martinez, L. F. (2018). Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(4), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12435

- Yoon, S., & Park, Y. (2021). Does citizenship behaviour cause ethical consumption? Exploring the reciprocal locus of citizenship between customer and company. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00130-1