ABSTRACT

The global tourism industry was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. New economic, social and political realities have emerged, and destinations are facing the changes. This research compares three popular destinations among Chinese tourists (i.e. Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore) to illuminate key political economic shifts of tourism in Southeast Asia in relation to China amid of the unfolding ‘new normal.’ By conducting a qualitative review and content analysis on publicly available data (e.g. media stories and public documents), the article contributes to a burgeoning body of knowledge on the impact of the pandemic wipe-out of the tourism industry and the context-dependent responses across destinations. The study reveals that established attitudes toward tourism have been challenged, as China and its major host countries learn to live with a weakened tourism industry. Whilst the three countries attempt to diversify their tourism economy, their dependency on the Chinese in their tourism and economic development will possibly deepen even though the post-Covid Chinese economy has slowed down. The comparison illustrates the different types of China-driven forces affecting these countries, highlighting the nuances and shades of understanding tourism political economies in these Southeast Asian countries.

摘要

全球旅游业受到新冠肺炎疫情的严重影响,经济、社会和政治的新现实随之出现,目的地也面临着变化。这项研究比较了中国游客喜爱的三个热门目的地(即柬埔寨、马来西亚和新加坡),以阐明在“新常态”背景下,东南亚旅游业与中国相关的主要政治经济转变。通过对公开可用数据(如媒体报道和公共文件)进行定性评价和内容分析,这篇文章有助于学术界深入理解新冠疫情对旅游业的影响以及各目的地的相关反应。此项研究表明,随着中国及其主要东道国学会与低迷的旅游业共存,之前人们对旅游业的既定态度受到了挑战。尽管这三个国家试图实现自身旅游经济多元化,同时中国经济在新冠疫情后放缓,但是它们在旅游和经济发展方面对中国的依赖可能继续加深。这一比较解释了影响这些国家的不同类型的中国驱动力,突显了这些东南亚国家对于旅游政治经济理解的细微差别.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted global tourism, and many destinations are now rebuilding their battered tourism economy. In Southeast Asia, like in other places, destinations are hoping for a return of tourists from China. The economic, social and political terrain in China has changed since the pandemic. Apart from economic challenges, the Chinese authorities have galvanized senses of nationalism in the populace, and introduced social economic policies that are more inward looking (The Economist, Citation2022). A reopened China is different from the pre-pandemic one, as its economy is facing challenges. It remains to be seen if destinations that used to be popular among Chinese tourists before the pandemic will be prepared for a changed China. Similarly, many countries have also evolved and their old attitudes toward tourism have been challenged, as they learn to live with a weakened tourism industry. As will be elaborated later, new configurations are emerging as the local tourism political economy evolves.

To offer an in-depth understanding of these new configurations, this paper provides a comparative analysis using evidence from three nearby Southeast Asian countries, namely, Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore – all of which were heavily dependent on Chinese tourists prior to the pandemic – to illuminate the key political economic shifts in the tourism sector of these countries. In addressing the effects of the pandemic tourism wipe-out on these China-dependent tourism political economies, this study offers a novel perspective as no work so far has looked into this dimension of the tourism ‘new normal.’

Based on comparative content analysis of various publicly available sources of data (such as media stories and public documents), this research addresses three issues. First, as we look into the ways in which the crisis disrupted the pre-pandemic tourism industry in Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore, our study discusses how China – as a geopolitical force – will upset the tourism political economies of the different host countries in a myriad of ways beyond how it has been understood prior to the pandemic. In doing so, this study reveals salient political and economic features of tourism in these places. Second, the article evaluates the ‘rethinking’ of the implications of Chinese outbound tourism. Tourism recovery in the three countries central to our study has progressed significantly in 2023, as Chinese tourists enter into the foray again. As these countries enhance links to Chinese investors and visitors, our analysis reveals how such relations entail not only touristification but possibly also sinification with far-reaching implications for the tourism political economy. Third, in using an ‘extreme comparative method’ (Shelley et al., Citation2019), we highlight the contexts and circumstances that shape the tourism political economies of these – widely diverging – places in relation to China. The comparisons between these countries illustrate the different types of China-driven forces that affect the countries differently, foregrounding the nuances and shades of understanding tourism political economies in the Southeast Asian region.

Literature review

The political economy of tourism is often assumed rather than researched upon. It broadly examines the relationships between the economy and politics, and the power-relations between interest groups in society.

As alluded to, tourism is a global industry and the political economy of tourism extends across borders. For example, Bianchi (Citation2018) reviews the political economy of tourism development, and highlights that, among other things, tourism plays a central role in the integration of developing economies into the global economy through the developmental state strategy. How the tourism industry is organized and structured in a destination is not only determined by domestic stakeholders but also by international players through investments, developmental aid and even visitors. Following Mosedale (Citation2016), the emergence of neoliberalism has affected – in myriad ways – the political economy of tourism via privatization of national assets, corporatization of the public sector, creation of markets, deregulations, counter consequences and self-sufficiency of individuals and communities. For instance, because the medical health industry has been deregulated and corporatised in many countries, medical tourism has advanced, resulting in negative impacts on citizens, as more medical staff members move toward the more lucrative visitor market and toward visitor-driven specializations, such as plastic surgery and hair-transplantation.

The interactions between geopolitics, soft power and political economy are key to understanding Chinese traveling abroad (Bennett & Iaquinto, Citation2021; Huang, Citation2022). In particular, these interactions allow us to see how the political economy is spatialized, particularly across borders of polities, countries and territories, and hence the ‘geography’ of the political economy. The ways in which the political economy has been ordered geographically have been key to much recent work concerning China and its engagements with Southeast Asian nation-states. Examining Chinese patriotic tourism in the disputed South China Sea, Huang (Citation2022) argues that tourism is a geopolitical activity aimed at socializing Chinese nationals into territorial thinking. The spatialization of political economy across nation-states thus allows us to reframe tourists beyond classical economic terms and to see them as calculative pragmatic political economic actors operating across geographical space (Huang, Citation2022) involved in China’s social territorisation of South China Sea. Such tourism geopolitics can also be seen at China’s ‘borders.’ Ong and du Cross (Citation2012), for instance, examine China’s expanding influence when Chinese visitors and would-be Macao tourists were seen to negotiate the territory’s postcolonial motifs, and Su and Li (Citation2021) discuss the subordination of tourism to security issues at border landscapes. The geopolitics of hosting Chinese tourists in less-known markets such as the Arctic has also been examined by Sokolíčková (Citation2021) who argues for Svalbard’s travel companies to claim expertise and to gain trust when working with the Chinese in order to overcome the mistrust and stereotyping consequent to the lack of prior warm geopolitical relations. On the opposite end, tourist perceptions of geopolitical risks associated with potential destinations also shape their travel decision significantly (Hailemariam & Ivanovski, Citation2021).

Chinese tourism’s political economic force also has a ‘soft’ and cultural dimension (Xu et al., Citation2020). In Southeast Asia, the region outside China’s two Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macao most visited by Chinese outbound tourists (Johnson et al., Citation2017), Chinese identities have extended beyond the more obvious economic workings of tourism to operate in relevant and multifaceted ways including the maintenance of diasporic communities, traditions, events and mobilities (Ong et al., Citation2017). Chinese soft power has also been used in more general ways as to win political and economic friends and garner support for China (Chen & Duggan, Citation2016; Xu et al., Citation2020). Such soft power implications have intensified in the years leading up to the viral pandemic as a result of the launch of China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative in 2013 (Chen & Duggan, Citation2016).

Methodology

Drawing on an approach that is problem-centered, focused on real-world and practice-oriented issues and outcomes, this paper centers on ‘what works’ rather than explicitly seeking to establish an absolute and objective standard (Frey, Citation2018). It uses a realist comparative analysis around responses to Chinese tourists in three popular Southeast Asian destinations: Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore.

A comparative method conceptually utilizes ‘control through common features’ or ‘most similar systems’ approaches to minimize variables (Pearce, Citation1993, p. 22). By setting common bases, the theoretical development is encouraged when differences are identified, as empirical data are tied to their own social structures and institutions (Baszanger & Dodier, Citation1997, pp. 16–18). The research team has listed out a series of common research questions on how destination authorities responded to the increasing number of Chinese tourists in their jurisdictions. Key terms guiding such questions included: ‘China AND tourism AND [case-study location – e.g. Singapore];’ China AND tourist AND [case-study location – e.g. Malaysia/Kuala Lumpur]. By doing so, we examine their strategies, explaining their similarities and differences within each country’s circumstance and context. This also reveals the political economy within the destination, and how China – as a significant market – fit into their post-COVID tourism recovery plans. The questions posed reflect the plans, the anticipated importance of the Chinese outbound market, and how that market will influence the local political economy of tourism. It also reveals the soft power of tourism, and the diverse geopolitical positions of China in these countries.

To respond to the research questions, the research team conducted a qualitative online media content review and a content analysis of the key policy documents following the established process by Simon Fraser University (Roberts, Citation2021). This approach yielded an in-depth interpretive content analysis (Altheide & Schneider, Citation2013). Media review is an effective method as it captures a picture of patterns that might affect and influence our thinking and perceptions of our day-to-day life (Potter & Riddle, Citation2007) and is a series of societal snapshots free from the researcher’s influence (Gavrilov, Citation2022).

Broad and narrower searches of key terms were conducted between 1 January 2017 and 29 November 2019 and from 1 December 2022 and 15 January 2023. This timeframe was chosen to ensure the relevance and timeliness of the information. The broad search included the following terms: ‘Chinese tourism,’ ‘Chinese tourists;’ ‘Chinese outbound tourism.’ The narrower search included the following groups of terms: ‘China’ AND ‘tourism’ AND [destination location – e.g. ‘Singapore’]; ‘China’ AND ‘tourist’ AND [destination location – e.g. ‘Cambodia’]. Key term search was done via the media database Factiva and other sources that were narrowly local but contextually relevant (e.g. theonlinecitizen.com (Singapore)). Google News has also been used to ensure a better coverage of the terms.

These data and data sources were also approached with a sense of ‘ethnographic sensibility’ (Shore & Wright, Citation2011) whereby textual and policy materials are rigorously and intuitively examined in line with the societal context they were embedded in. Unlike ‘objective’ content analysis, authors relate to and interpret the media and policy content like how they would in the field, taking into account in real-world settings the media is entangled in/with. Such ethnographic sensibility is possible as the authors of this paper possess extended field experiences in respective countries they contribute to. The following sections present the findings for subsequently Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore.

Findings

Case 1: Cambodia

Cambodia’s vision for a prosperous future is to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030, and the tourism sector is poised to play a pivotal part in this scenario. Dubbed the ‘green gold,’ the Cambodian government’s economic projections lean heavily on international tourism (Hin, Citation2022a). In pre-COVID Cambodia, international tourism has shown consistent growth since the early 2000s and has become the country’s foremost GDP earner. Between 2000 and 2017 tourist numbers surged from 450,000 to 6.6 million in 2019, with an average annual growth rate of 16% (WTTC, Citation2020). Before the pandemic hit, international tourist arrivals were expected to grow by 5.2% per annum to about 8 million in 2028 (WTTC, Citation2018). In 2019, the total contribution of tourism to the Cambodian economy was USD 7.1 billion or 25.8% of GDP, and was forecast to rise by 6% per annum to 13 billion in 2028 (WTTC, Citation2022). The majority of international visitors were from Asian countries, with the Chinese topping the list of arrivals as Cambodia welcomed some 2.3 million Chinese tourists in 2019, which accrued to 27% of all arrivals (Sorn, Citation2019). Tourism Minister Thong Khon expected the numbers to rise to 3 million in 2020 and 5 million in 2025 (Xinhua, 10–05-Citation2019).

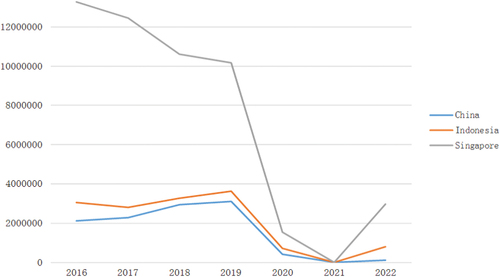

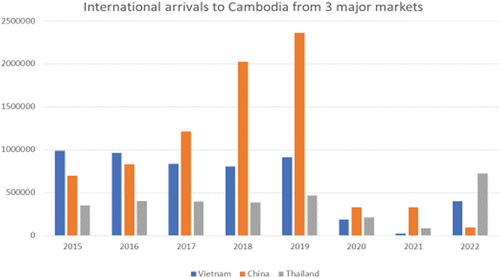

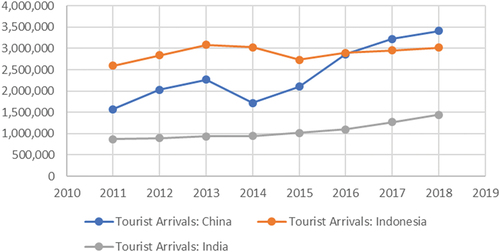

The pandemic has affected Cambodia’s tourism sector badly. Since 2019, international arrivals have plummeted by 97% which entails a 90% revenue loss. China’s zero-COVID policy made visitor flows from China dry up almost completely (). The tourism and travel industry merely accounted for 4.7% and 7.2% of domestic product (GDP) in 2021 and 2020, respectively, down from the whopping 25.8% recorded in 2019 (WTTC, Citation2022). An estimated 3,000 tourism-related businesses have closed down and 45,400 jobs have been lost (Amarthalingam, Citation2020).

Table 1. International arrivals and revenues (MoT, Citation2020; Citation2022).

The Cambodian borders were closed for almost 2 years (). As the COVID pandemic reached its peak, a comprehensive intervention package was launched, keeping the tourism sector on life support. The government rolled out cash support payments (between US$ 30 and 40) to nearly 2,000 tourism workers who have been suspended due to the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, tourism businesses received a total exemption from all taxes until the end of 2022. And to support companies involved in the tourism value chain to restart operations, a US$150 million Tourism Recovery Co-Financing Scheme was set up that offers loans against lenient conditions (Hom, Citation2022e). This project is part of the ‘Strategic Framework and Programmes for Economic Recovery in the Context of Living with COVID-19 in a New Normal 2021–2023,’ a comprehensive roadmap to guide the economy as the coronavirus becomes endemic (Hom, Citation2022e).

Figure 1. International arrivals to Cambodia from the three major markets (MoT, 2018, Citation2020; Citation2022).

In the early days of the pandemic, many Cambodians enjoyed the absence of international tourists from the country’s major attractions, as business owners expected that mounting domestic tourism would compensate for the revenue loss suffered. Domestic tourism was indeed the lifesaver for many Cambodian tourism businesses. In the first 6 months of 2022, Cambodian holidaymakers made 6.33 million domestic trips, up by 219.3% on a yearly basis, as an average of 300,000 internal journeys are recorded each week. At that time, local tourists spent nearly $500 million or an average of $500 based on the expenditure of a family of five (Hom, Citation2022a). However, as domestic travel revolves around special festivals and weekends, it is insufficient to meet the needs of local tourism suppliers (Amarthalingam, Citation2022). The initial optimism surrounding the domestic tourism industry has given way to people eagerly awaiting the return of international tourists, in particular, the Chinese.

As a small, export-orientated economy, Cambodia faces major challenges as world trade growth slows. In particular, the sluggish recovery of the tourism sector – blamed on China’s lockdown that has only been lifted at the end of December 2022 – is cause for concern. Dependence on the Chinese market remains extremely high (Amarthalingam, Citation2022), which reflects the pivotal role of China in Cambodia’s economic growth at large. Under the Belt and Road (BRI) framework, China has become Cambodia’s largest foreign investor, bilateral donor, trading partner, rice buyer and source of foreign tourists (Sok, Citation2019). From infrastructure and connectivity development to cross-border trade and tourism, the benefits from being among China’s most favored nations are quite obvious. As in all other friendships that China pursues across the world, access to cheap labor, markets and natural resources is paramount. However, Cambodia’s true value is of a geo-political nature. Cambodia is important to secure China’s military access to the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea (ABC, Citation2019).

Delighted at China’s move to reopen to inbound and outbound tourism in early January 2023, prime minister Hun Sen expressed his expectation that soaring visitor arrivals from China would encourage current and long term growth in the Cambodian economy (Hin, Citation2023). As travel from China is about to resume, the government has prepared a ‘Special Tourism Policy’ with the return of the Chinese tourists in mind. New developments are envisioned to add value to the ailing sector by attracting long-stay and repeat visitors, high spenders, potential investors and entrepreneurs. While a typical traveler spends an average of $700–800 per trip to Cambodia, the ‘special tourist’ is envisioned to spend $2,000–3,000 (Hom, Citation2022d). Recently, the Ministry of Economy and Finance awarded a Master Plan consultancy contract to a top Chinese institute for the development and transformation of Preah Sihanouk province into a ‘Model Multi-Purpose Special Economic Zone,’ dubbed as the ‘second Shenzhen city,’ Southeast Asia’s next logistics and resort hub and innovation center (Hom, Citation2022c). In support of this project, the accessibility of Cambodia’s key attractions is improved by building new Chinese-funded airports, increasing the number of flights from more locations in China. Also, more luxury accommodations are being established, such as a new five-star hotel in Sihanoukville built with a $168 million injection from a Chinese investor (Hin, Citation2022d), and the exclusive island resorts just off the coast of Sihanoukville financed with Chinese money (Hom, Citation2022b).

For the Cambodian economy, however, the benefits from the Chinese outbound travel boom have been lopsided. Most of the revenues generated and new jobs created remain with the Chinese tour operators as Chinese travelers are serviced in hotels and by travel companies that are China-based and Chinese-owned (O’Byrne, Citation2018). Consequently, Cambodia’s revenue leakage to overseas agents and investors, estimated at 40% in 2017, is one of the highest in Asia (World Bank Group, Citation2017). Chinese investment in Cambodia’s real estate market is almost exclusively aimed at the Cambodian political elite, as well as Chinese tourists and businessmen, driving up prices and making housing unaffordable for most Cambodians (Heng, Citation2018). Land disputes between Chinese-owned companies and developers remain unresolved and state institutions fail to manage conflicts flaring up between locals and Chinese business people and tourists (Business Insider, Citation2018). The impact of the growing number of Chinese tourists is also visible in the streets of Cambodian tourist areas where the signage at places of interest, shops and restaurants is more and more often provided in Chinese language causing local antagonism (Kouth, Citation2019). This also affects the long-established and well-integrated Cambodian Chinese community as China’s rapid rise in the Kingdom has shaken up the traditional Chinese-language media (Hor, Citation2018).

Yet, there is a buzz around tourism as the sector has been singled out as the flagbearer of Cambodia’s post-COVID recovery. In 2022, Cambodia has made the most of its chairmanship of ASEAN and has wooed its neighbors to strengthen economic cooperation including tourism. The ASEAN nations are expected to fuel the successful re-launch of tourism in Cambodia post-pandemic, with Thailand and Vietnam among the top-source markets for arrivals (Hin, Citation2022e). Similarly, the campaign for the ‘Visit Cambodia Year 2023’ was launched and ‘destination Cambodia’ is being promoted in international settings among which India, China, Japan, South Korea, and Europe. The aim is to raise the allure of the Kingdom and push the ‘Cambodia as Sports Tourism Destination’ campaign as the host of the 2023 Southeast Asian Games and ASEAN Para Games (Hin, Citation2022c). Riding the waves of a ‘clean and green’ image, the Ministry of Tourism has identified ecotourism as key to post-COVID recovery, announcing the development of more nature-oriented tourism activities to draw in more domestic and international visitors, promote care for the environment, and help local communities protect forests and conserve the Kingdom’s natural resources (Hin, Citation2022b). Most Cambodian provinces have put in place long-term Tourism Development Plans comprising eco-tourism development, often in the shape of eco-resorts. The eco-dimension of such developments, however, seems to be more of a marketing instrument than a serious attempt at nature conservation by means of tourism.

Case 2: Malaysia

Tourism plays an extremely important role for Malaysia with regard to economic development. In the past few decades, international tourism grew steadily. In 2019, international tourist arrivals and receipts reached 26.10 million and RM 86.10 billion, respectively (). As an economic pillar, tourism industry contributed 15.9% of GDP compared with 10.4% in 2005, and it provided 3.5 million jobs (23.6% of total jobs) directly and indirectly for Malaysia in the same year (DOSM, Citation2020). Before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 was set as the 5th Visit Malaysia Year, and Malaysia expected to receive 30 million international tourists. Besides, tourism facilitates Malaysia maintaining its trade balance. The tourism industry generated USD 7 billion trade surplus for Malaysia in 2019, and the number is one of the highest in the Asia-Pacific (UNWTO, Citation2021).

Table 2. International tourist arrivals and revenues. Source: tourism Malaysia (https://www.tourism.gov.my/statistics).

However, Malaysia, like other countries, has been substantially affected by the pandemic. Its international tourism almost ceased to exist as countries strictly restricted travel and even closed their borders. In the meantime, Malaysia’s domestic tourism was seriously disrupted by the Movement Control Order (MCO). MCO refers to a series of nationwide quarantine and cordon sanitaire measures implemented by the Malaysian federal government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The implementation of MCO and other mobility restriction measures had largely curbed the spread of the outbreak, but the tourism industry was hit hard. It is estimated that Malaysia lost altogether RM 300 billion in tourist expenditure in 2020 and 2021 (Solhi, Citation2021). Only 4.33 and 0.13 million international tourists visited Malaysia in the 2 years, respectively, and the receipts also plunged significantly compared to the pre-COVID time (see the table above).

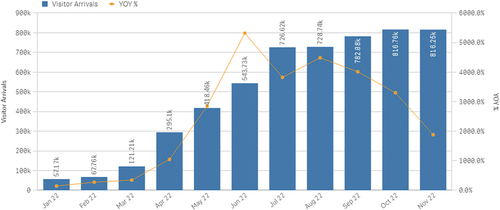

To revive the ailing tourism industry, the Malaysian government implemented various incentives to businesses and domestic tourists (The Star, Citation2022a). For example, e-vouchers were given to domestic tourists, and individuals could have a personal income tax relief up to RM1,000 for domestic tourism expenditure. Besides, RM85 million, as special assistance, was allocated to more than 20,000 tourism operators registered under the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture (MOTAC), as well as RM60 million funds for activities to promote domestic tourism (MOF, Citation2021). As a result, Malaysia’s domestic tourism received a boost, but it is not enough to fill the gap caused by the collapse of international tourism. Fortunately, Malaysia, along with the global easing of travel restrictions, reopened its borders to all international visitors on 1 April 2022, and its international tourism quickly bounced back. By August, Malaysia had achieved its initial target at 4.5 million tourist arrivals with RM11.1 billion in tourism receipts (Malay Mail, Citation2022). Then, it set a new target at 9.2 million tourist arrivals with RM26.8 billion in tourism receipts (Malay Mail, Citation2022). Yet, the progressive target is far less than the pre-COVID levels, and it will take some time to achieve a full recovery.

In the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, business owners were generally optimistic as they anticipated that domestic tourism could, to some extent, fill the gaps left by international visitors. Meanwhile, some Malaysian tourists even praised the absence of international tourists and thought that they could enjoy Malaysia more. However, domestic tourism performance continued to decline due to the impact of the COVID-19 and the MCO (). In 2021, the number of domestic trips only reached 66.0 million and decreased 49.9% compared to the previous year, and domestic tourism expenditure also decreased 54.5% to record RM18.4 billion (DOSM, Citation2022). To survive, many businesses have taken various contingency measures. For example, new products are introduced, such as virtual tours, airline’s flat fare deals, and hotel’s workation/staycation packages.

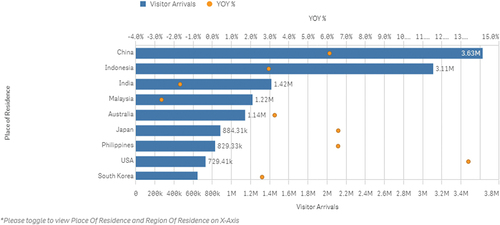

Malaysia has been a popular destination for Chinese tourists since receiving ‘Approved Destination Status’ from the Chinese government. The number of Chinese tourists to Malaysia steadily increased. In 2019, 3.11 million Chinese tourists visited Malaysia, which made China the 3rd biggest source country following Singapore (10.16 million) and Indonesia (3.62 million) (Tourism Malaysia, Citation2022). Malaysia even set 2020 as Malaysia-China Cultural Tourism Year with a target of receiving 5 million Chinese tourists (Xinhua, Citation2020). However, the number of Chinese tourists plummeted dramatically due to the COVID-19 related travel restrictions imposed by both China and Malaysia (Tourism Malaysia, Citation2022). After Malaysia reopened its borders, the number of Chinese tourists increased much slower than other major source markets (e.g. Singapore and Indonesia). Moreover, China has dropped out of Malaysia’ top three source markets in 2022 mainly because China persisted in a dynamic zero-COVID strategy.

Tourism-related businesses (e.g. travel agencies) look to tourists from India, ASEAN and other neighboring countries to replace the gap left by Chinese tourists (The Edge Markets, Citation2022). Nevertheless, the absolute importance of Chinese tourists is often mentioned by public media. It is widely acknowledged that Chinese tourists are indispensable for Malaysia to achieve a full tourism recovery. The private sector matter-of-factly expresses that Chinese tourists are needed to lift Malaysia’s underperforming economy (Kana, Citation2022). Malaysia tourism players believe that they will benefit immediately and immensely once China lifts its mobility restrictions for international travel (The Star, Citation2022b). Sam Chia, the CEO of Malaysian Chinese Tourism Association (MCTA) anticipated that China would lift the travel restrictions in the first-quarter of 2023, so he suggested Malaysia’s tourism players preparing for the arrival of Chinese tourists.

As expected, China reopens to international tourism from January 2023. The reopening of the world’s second-largest economy is seen as a very timely and significant boost for the Malaysian economy because domestic economic activities are projected to slow down amid increasing fears concerning a global recession. According to HSBC Global Research, China’s reopening could help Malaysia sustain its post-pandemic recovery, tourism and foreign direct investment (FDI) in particular (The Star, Citation2023). Although there were some debates on whether Chinese tourists should be banned after China’s initial announcement of reopening, the majority of policy makers and business operators welcome the entry of Chinese tourists to Malaysia. Tiong King Sing, MOTAC Minister, personally presented souvenirs to Chinese tourists at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) on 22 January 2023 (the 1st day of Lunar New Year). It is estimated that more than 1 million Chinese tourists will visit Malaysia in 2023, and the number may reach 50% to 80% of pre-COVID as long as there are enough flights and visa entry requirements can be further eased (The Star, Citation2023). MOTAC even targets 5 million tourist arrivals from China in the same year compared to 3.11 million in 2019 (Bernama, Citation2023).

Nevertheless, it should be noted that Malaysia’s tourism industry already experienced some difficulties before the pandemic as the number of international tourist arrivals stagnated around 26 million. Many in the government and industry argue that Malaysia is stuck in a comfort zone and is gradually losing competitiveness in comparison to neighboring destinations, such as Thailand (MOTAC, Citation2020). Besides, about half of Malaysia’s international tourist arrivals were from Singapore. To diversify source countries, Malaysian government and industry practitioners were targeting markets within the range of medium-haul flights, such as mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and India. Although the current pandemic imposes challenges, it also offers Malaysia an opportunity to rethink its tourism development strategy. In 2020, Malaysia launched a 10-year plan to break out of the comfort zone and improve competitiveness by developing sustainable and inclusive tourism (MOTAC, Citation2020). Malaysia aims to place itself as a global top 10 destinations for both international arrivals and receipts. Meanwhile, Malaysia will focus on high-value tourists, including those from China, in niche market segments, including ecotourism, sports tourism, health tourism and international conventions (The Star, Citation2022b).

Tourism has been seriously disrupted, but economic cooperation is, somehow, strengthened between the two countries. Malaysia is the first to establish official diplomatic relations with China in Southeast Asia (in 1974). Over the past 48 years, the two countries had an amicable relation, which laid a solid foundation for almost all aspects of bilateral cooperation. China had been Malaysia’s largest trading partner for 14 consecutive years with 17.1% share of Malaysia’s total trade, expanding by 15.6% to RM487.13 billion compared to 2021 (MITI, Citation2023). With regard to FDI, China accounts for 55.6% of the total FDI (RM87.4 billion) approved by Malaysia in the first half year of 2022 (MIDA, Citation2022). More importantly, the two agree to foster stronger ties under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (Jaafar, Citation2022). Economic cooperation, particularly international tourism, is susceptible to political tensions, so soured bilateral relations would bring negative impacts. For example, Malaysian politicians made some controversial comments on a few China-linked mega projects in Malaysia in 2018, and then Chinese tourist arrivals to Malaysia plunged by 30%-35% during China’s National Day holiday (Golden Week) in the same year (The Strait Times, Citation2018).

With closer economic ties, Malaysia’s reliance on China may gradually increase, meanwhile China’s soft power is arguably increasing in Malaysia. While 22.6% of Malaysians are ethnic Chinese, they are not given equal access to education, government jobs and business support (Long & Ooi, Citation2022). In contrast, they are very active in private sectors. Besides, most of them can speak fluent Mandarin or other Chinese dialects (e.g. Cantonese). Thus, they gain more benefits from Chinese tourists and investors compared with other ethnic groups. Due to the unequal distribution of benefits, Malaysia’s own ethnic tensions, between the majority Malay population and the minority Chinese population, may even be aggravated. As Malaysia has to maintain a positive relationship with China – if it hopes to receive more Chinese tourists and investments – the country may face an awkward dilemma caused by its internal ethnic tensions and instrumental relations with China.

Case 3: Singapore

Singapore’s dependency on tourism in pre-COVID times is modest in terms of its contribution to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product − 4% in 2019 (STB, Citation2022). However, it has been a steadily rising industry. Tourism has grown strongly through almost six decades of Singapore’s modern and independent existence: from a modest 99,000 in 1965, to 19.1 million in 2019 at its peak, before falling dramatically in 2020–2022 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (STAN, Citation2022). At its peak in 2019, international visitor arrivals more than tripled the country’s resident population of 5.7 million (Singstat), while Citation2021 saw a record low in the number of visitor arrivals in Singapore at 329,985. Prior to the pandemic, total international visitor arrivals and total tourism receipts grew at an annual average of 4.5% and 5%, respectively, for more than a decade in 2007 to 2019. Singapore’s dependency on tourism can also be seen from the chain of suppliers and industries connected to tourism. From F&B to hospitality, much of the service and transport industries rely on tourism for that boost in numbers and have suffered during the years of pandemic border closures.

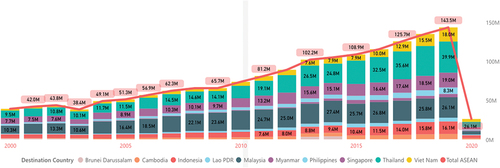

In 2019, Singapore was ranked as the 25th most visited country in the world by visitor arrivals and 22nd in the highest amount in international tourism receipts (Erh, Citation2021). As compared to its neighbors in Southeast Asia, Singapore accounted for 13% of all international visitor arrivals in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries in 2019 (see ), and despite being a much smaller destination as a city-state of only 728.6 km2, it received the third highest number of international visitors at 19.1 million after Thailand (39.9 million) and Malaysia (26.1 million).

Figure 3. ASEAN visitor arrivals by destination country 2000–2020. Figure generated using ASEAN Visitor Arrivals Dashboard (Citation2021).

The importance of China tourism for Singapore and dependency of Singapore’s tourism industry on China tourists is evident in sheer numbers of tourist arrivals from China. shows the tourist arrivals of China, Indonesia, and India – the top three source countries in 2018 and how they performed since 2011. Most notably, year 2017 is a watershed for the competition between Indonesia and China for the top spot. China, for the first time, overtook long-time top-source country Indonesia and has held on to that spot until 2019.

Figure 4. Tourist arrivals: top three source countries: China, Indonesia and India.

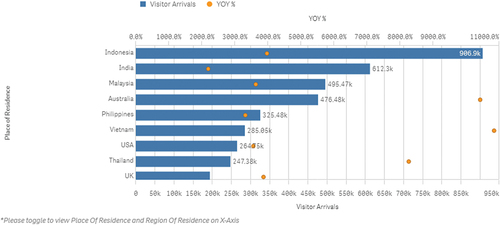

A comparison of visitor arrivals between 2019 () and 2022 (), however, highlights how the situation in Singapore has changed – far from being the top-source country for Singapore, in its tourism recovery in 2022, China only contributed 111,180 visitor arrivals and is now ranked as the 12th top-source country for Singapore.

Figure 5. Visitor arrivals in Singapore by geography (2019).

Figure 6. Visitor arrivals in Singapore by geography (2022).

Singapore’s tourism economy has suffered the loss brought about by significantly reduced international tourism arrivals, including that of China’s. During the years of pandemic measures and consequent of the sharp decline of Chinese tourists, Singapore’s tourism has reduced its dependency on China by switching to its initial reliance on tourists from its immediate neighbors Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand and the source markets of India, Australia, U.S.A. and UK. Aware of the need to keep its borders and economy open, Singapore initiated policies geared at allowing travel to resume. In the first instance, these targeted essential business travel, official travel and family reunion travel through the first set of Safe Travel Lanes (September 2020 to April 2022). Under the Safe Travel Lanes, travelers from different countries were determined to be of different risk levels and over time faced changing eligibility requirements, SHN (Stay-Home Notice), and testing regimes upon arrival. While of varying success and effect, Green or Fast Lanes and Air Travel Bubbles were also negotiated bilaterally since 2020 at a time where international travel in Asia was still largely curtailed. Once it was deemed that the general public within Singapore had been sufficiently vaccinated, Vaccinated Travel Lanes (VTL, September 2021 to April 2022) that allowed vaccinated travelers from selected countries to enter Singapore without SHN; and eventually the Vaccinated Travel Framework (VTF) that replaced the VTL and Safe Travel Lanes schemes in April 2022 allowed the gradual resumption of general travel in and out of Singapore. This has enabled a rapid rise in numbers of international arrivals and a pronounced recovery in Singapore’s tourism sector, especially since April 2022 (see ).

China, on the other hand, pursued a dynamic zero-COVID strategy and maintained amongst the strictest border restrictions globally. When China’s international travel restrictions eased in early 2023, Singapore did not impose any new border measures on arrivals from China.

In addition to being a key limiting factor in tourism recovery, the sharp decline of Chinese tourists also prompted discussions of eradicating dependencies on single source markets for Singapore’s tourism, including that of China’s. At the start of the pandemic, a leaked audio recording in February 2020 of then Minister of Trade and Industry, Chan Chun Sing, allegedly suggested the need to diversify tourism source countries in Singapore. In the recording, he was quoted to have said that ‘I will not allow the Chinese tourists to grow more than 20%. Not the Indian market, not the Indonesian market, because we will be held ransom. You look at what happened to Taiwan, South Korea, Japan’ (Wong et al., Citation2020). This was hardly mentioned again in public media, perhaps because of the political sensitivities surrounding these statements, but it should be noted that such risks became especially apparent in Singapore because of the pandemic.

General sentiments on the ground, however, show that Singapore expects itself to remain a prime destination for Chinese tourists in a post-COVID future. This is especially true because throughout the pandemic, Singapore has been reported as a safe destination with excellent COVID-management policies and record COVID-related low death rates (Lew, Citation2022). Singapore has also emerged as and is reported widely to be a destination for many rich Chinese migrants fleeing unpredictable and excessively strict COVID-management policies at home (He & Cai, Citation2022), thereby suggesting a possible future surge of high-end Chinese tourists because of travel for the purpose of visiting friends and relatives in time to come.

China’s soft power has operated through both discourses of China tourism promotion in Singapore and narratives of Singapore’s tourism recovery. China’s topping of the Singapore’s table for the top-tourism source country was widely reported across all Singapore media outlets, including those reviewed in this paper. The importance of Chinese tourism – in terms of its actual numbers, tourism receipts, and potential for growth – is heavily emphasized in official or industry contexts. The expectation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was that Singapore will continue to ride the wave of increasing Chinese outbound tourism and was a favored destination due to its many natural advantages and affinities with Chinese tourists. Seeing China as a key economic and political ally, social and public discourses in Singapore continued to paint China in the positive light – including the rapid erasure of Minister Chan’s remarks about reining in Chinese tourist numbers. Unlike potential destinations such as Japan, Italy and India, Singapore has also been steadfast in its support of China tourists and has not imposed COVID-related restrictions such as mandatory testings.

It should be noted, however, that – while most in the industry understand that China tourists will resume its dominant position in Singapore once its borders reopen – the rhetoric around tourism recovery in Singapore in 2022 has so far hardly mentioned China’s role in this, except to acknowledge how full recovery without Chinese tourists would be impossible (Hamzah, Citation2022). This is a marked shift from media sources prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, where Singapore’s attractiveness to China was widely celebrated in public forums while China’s role in contributing to Singapore’s tremendous growth in tourism was stated in almost every media publication up until 2019. It is unclear whether this lack of specific mention toward China is due to an actual attempt to diversify Singaporean tourism markets or simply because the politics surrounding recent COVID-management policies mean that most in the industry refrain from mentioning Chinese tourists’ return at this time. However, the Singapore Tourism Board continued engagement with China markets throughout the pandemic, and continued efforts by Singapore Airlines to resume flight connectivity despite existing restrictions could be observed (Singapore Airlines, Citation2022). Notably, both Singapore Airlines and Scoot have been at the forefront of resuming flight routes between Singapore and China ever since China relaxed its zero-COVID strategy regarding border control. As of January 2024, Singapore Airlines served seven destinations, while Scoot served 17 destinations in China.

Discussion and conclusion

The tourism industry in Southeast Asia, with no exception, has been seriously disrupted by COVID-19. This research conducted a comparative analysis, through online media stories and public documents, around responses to Chinese tourists in Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore so as to illuminate relevant changes of tourism in the region in relation to China amid of the unfolding ‘new normal.’ By comparing similarities and differences of the three destinations, the current study provides some meaningful lessons for political economy dialogs of tourism in Southeast Asia. below summarizes the findings across these three countries.

Table 3. Similarities and difference in response to fluctuations in Chinese outbound tourism.

In the evolving living-with-COVID situation, it remains unclear how the industry and the tourism political economies are reshaping the region. The battering of the tourism industry has reconfigured relationships between stakeholders, such as politicians, communities and big tourism industry. Subsequently, the tourism political economy has also changed. While many of the reactions and responses to the pandemic are similar, there are also differences. We draw lessons based on the three issues we set out to address. Before the pandemic, there were concerns in many destinations about Chinese influence not just the tourism industry but also in other economic, political and cultural aspects of life. The pandemic stopped the momentum of Chinese visitor influx and influence, as countries evaluate their future and the ‘new normal.’

Our first issue addresses this ‘new normal’ querying whether China as a geopolitical force will upset the tourism political economies of the different host countries in new ways beyond how it has been understood prior to the pandemic. As a common denominator, authorities in the three destinations look forward to welcoming back visitors from China. These countries gradually reopened their borders in 2022 but China embraced a zero-COVID strategy then. Their international tourism revenues recovered as they sought other markets. Diversification away from China is not restricted to the tourism industry in these countries, as many economies and supply-chains learned their lessons as they were crippled by their high reliance on China. While lessons have been identified, only time will tell if tourism authorities and businesses have taken the lessons seriously; there is no explicit acknowledgment for and discussion on developing a more diverse and robust tourism economy, away from the Chinese outbound tourist market. Chinese geopolitical influence, as exerted through tourism, will remain strong albeit reconfigured in the ‘new normal,’ and it will become stronger when destinations become more dependent on the Chinese outbound visitors and on Chinese investments (see Bennett & Iaquinto, Citation2021; Huang, Citation2022).

The second issue pertains to ways in which touristification and sinification processes might change after the pandemic. Complaints against over-tourism and the presence of Chinese visitors disappeared during the pandemic in these destinations. However, the economic impact was significant. As Chinese citizens can travel again, strategies to welcome them back are quickly put into place. These destinations may want to reduce their reliance on Chinese visitors, but they do not want to decimate the lucrative source of tourism income. A diversified visitor market strategy makes good longer-term business sense but more often than not, it is more difficult and costlier for businesses to develop new markets than to go more deeply into established ones. China has a large population, and focusing on the multiple parts of China makes short-term strategic sense. Regardless, established amenities, such as the Chinese payment systems and Chinese signages, and having established a presence on Chinese social media, suggest that sinification has begun. Also, in the current political and economic environment, tourism inevitably entails the transmission of soft power, especially for China, while shaping the local political economy. Besides economic benefits, host communities and businesses attempt to understand and to cater to the needs of Chinese visitors and attract Chinese tourism investments. Community members do not only get familiar with the presence of Chinese visitors, they may also become more sympathetic toward them (cf. Ong et al., Citation2017). Unfortunately, the opposite may also occur, and the Chinese authorities have responsively launched campaigns for their outbound citizens, asking them to behave in more local-culturally sensitive and respectful ways when overseas. In this context, sinification is part of globalization.

We also aim to draw comparative lessons that highlight contexts in the tourism political economies of Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore – to address the third and final issue raised. The abovementioned comparison illustrates the different types of China-driven forces affecting these countries differently. All these countries were heavily dependent on Chinese tourists prior to the pandemic. China reopened its borders on 8 January 2023, and despite concerns about the new wave of COVID-19 infections spreading throughout China, these three (and other Southeast Asian) destinations welcome back Chinese tourists without any extra COVID-19 testing requirements. In contrast, some countries, such as Australia, Japan and South Korea, introduced new virus testing requirements for travelers from China then. These latter destinations were accused of discrimination on Chinese social media, and the Chinese government stopped issuing short-term visas to Japanese and South Korean citizens in retaliation. Were Japan and South Korea overacting or were the Southeast Asian nations ‘kowtowing’ to China? The answer is probably found in both. The Chief Medical Officer of Australia stated that there was ‘no sufficient public health rationale’ (Evans, Citation2023) to introduce mandatory COVID-19 testing on travelers from China. The restrictions insisted by the immigration authorities must consider public opinions and political expediency. Conversely, Singapore’s rejection of COVID testing Chinese travelers resonates with the city state’s tried and tested survival strategy amid global uncertainty. Echoing the illustrious Singaporean prime minister, the Minister for Home Affairs explains: ‘As a small country, we have to be clear on what are our principles. We must always put Singapore’s interests first, and never be afraid to act in our own interests’ (Lee, Citation2023).

The disputes over the treatment of Chinese tourists after China’s border reopening may simply be a political show to serving domestic political purposes in some destinations, but it has consequences. Under the influence of media propaganda, some Chinese tourists will shift their destination preferences (cf. Hailemariam & Ivanovski, Citation2021). Thus, the three and other Southeast Asian destinations may become even more popular among Chinese tourists. This is beneficial to big tourism industry player and also pro-China politicians, but increasing reliance on Chinese tourists might threaten these destinations’ economic and social development for a long term. As a matter of fact, some policy makers already realized the necessity to diversify their source markets prior to the pandemic, which is applicable to other destinations in relation to any major source country. Due to the political sensitivities, such discussion is rare on public media in destinations that wish to maintain an amicable relation with China, especially when local politicians and big industry players can benefit from such bilateral relations.

However, the process for diversification is rather slow as it is much easier to attract more Chinese tourists than develop new source markets. As long as maintaining a warm relationship with China, these destinations can benefit from China’s booming outbound tourism without much effort. In brief, Southeast Asian nation-states need China for economic and political reasons. Similarly, China needs steady and supportive neighbors in the region (cf. Chen & Duggan, Citation2016; Xu et al., Citation2020). Take the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative, for example, Southeast Asian countries are essential for the success of the strategy (Chen & Duggan, Citation2016). As the two sides recognized the significant role of each other, ASEAN and China established a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2021. In such landscape of political economy, Southeast Asian destinations are susceptible to Carrot and Stick ‘threats’ from China. Meanwhile, they are likely to entail a process of sinification when they accommodate more Chinese tourists and investors. To ensure sufficient geopolitical space, destinations in the region need to rethink how to keep a safe and also close distance with China for a balanced geopolitical economy.

With regard to industry development, Southeast Asian destinations may encounter different pathways. Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore represent three economic levels. Both Malaysia and Singapore are industrialized, and their economic structures are healthier than Cambodia’s. Seeing the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Malaysia and Singapore are more likely to further optimize their economic structure and improve their tourism industry’s resilience toward future crisis. Cambodia has not finished its industrialization process, so it probably will continue to rely on international tourism for foreign exchange income. As a result, Cambodia’s reliance on international tourism may deepen. Besides, Cambodia may be further touristified to cater to international tourists and sinified to cater to Chinese tourists. Regardless, in all these countries, China’s outbound tourist market will exert influence on the local tourism political economy. Future research will monitor the situation as it evolves and identifies the progress made and obstacles encountered against the backdrop of ongoing transformations of the tourism political economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fei Long

Fei Long received his PhD from the National University of Malaysia (UKM). His industrial career spans over different regions, including East, South, Southeast Asia and South America. His research focuses on China’s outbound tourism, cross-cultural communications, big data, social justice and ASEAN studies.

Heidi Dahles

Heidi Dahles is an adjunct professor at the School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania. Her research interests include local livelihoods, resilience and social enterprise, in particular in the tourism industry, in Southeast Asia.

Chin Ee Ong

Chin Ee Ong is Professor of Cultural and Tourism Management at Macao Institute for Tourism Studies. His research examines cultural and heritage tourism as important and complex social and material phenomenon. He is Co-Editor-in-Chief of Tourist Studies.

Can-Seng Ooi

Can-Seng Ooi is a sociologist and anthropologist at the University of Tasmania. He is also Professor of Cultural and Heritage Tourism. To find out more about him, visit http://www.cansengooi.com.

Harng Luh Sin

Harng Luh Sin is a Senior Lecturer in College of Interdisciplinary & Experiential Learning, Singapore University of Social Sciences. She is an established scholar in the areas of volunteer tourism and responsible tourism. Her current research looks at topics of Chinese outbound tourism, and experiential learning from Singapore.

References

- ABC. (2019). US official suggests Cambodia may host Chinese military assets at naval base. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-02/

- Altheide, D. L., & Schneider, C. J. (2013). Qualitative media analysis (Second ed.). SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452270043

- Amarthalingam, S. (2020). Wither tourism? Can Cambodia resuscitate the sector post-covid-19? Phnom Penh Post, Posted on July 23, 2020.

- Amarthalingam, S. (2022). Chinese tourists 2.0 – coming anytime soon? Phnom Penh Post, Posted on May 19, 2022.

- ASEAN. (2021). ASEAN Visitor Arrivals Dashboard. ASEAN Statistics. https://data.aseanstats.org/dashboard/tourism

- Baszanger, I., & Dodier, N. (1997). Ethnography: Relating the part to the whole. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice. Sage.

- Bennett, M. M., & Iaquinto, B. L. (2021). The geopolitics of China’s Arctic tourism resources. Territory, Politics, Governance, 11(7), 1281–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1887755

- Bernama. (2023). MOTAC targeting five million tourist arrivals from China this year - Tiong. https://www.bernama.com/en/general/news.php?id=2158385

- Bianchi, R. (2018). The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.08.005

- Business Insider. (2018). China investment boon comes with a price. Phnom Penh Post, Posted on February, 5 2018.

- Chen, Y. W., & Duggan, N. (2016). Soft power and tourism: A study of Chinese outbound tourism to Africa. Journal of China and International Relations, 4(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.jcir.v4i1.1514

- DOSM. (2020). Tourism satellite account 2019. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=111&bul_id=dEZ6N0dYUDJEWkVxMzdOalY3UUJSdz09&menu_id=TE5CRUZCblh4ZTZMODZIbmk2aWRRQT09

- DOSM. (2022). Performance of Domestic Tourism by state, 2021. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=472&bul_id=QmNWcG1TdVo0WVlBZVQ4cGVLYlQvdz09&menu_id=b0pIV1E3RW40VWRTUkZocEhyZ1pLUT09

- The Economist. (2022, July 13). Xi Jinping has nurtured an ugly form of chinese nationalism. https://www.economist.com/china/2022/07/13/xi-jinping-has-nurtured-an-ugly-form-of-chinese-nationalism

- The Edge Markets. (2022). Special report: Malaysia looks to Indian and Indonesian tourists to replace the Chinese. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/special-report-malaysia-looks-indian-and-indonesian-tourists-replace-chinese/

- Erh, J. (2021). COVID-19’s economic impact on tourism in Singapore. ISEAS Perspective, 1–18.

- Evans, J. (2023, January 3). Chief medical officer paul kelly advised against mandatory COVID-19 testing for travellers from China. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-01-03/chief-medical-officer-opposed-mandatory-covid-test-china-travel/101822918

- Frey, B. (2018). The SAGE Encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vols. 1-4). SAGE Publications.

- Gavrilov, K. (2022). Who is to blame for the terrorist attack? Comparison of content analysis and survey data as sources of responsibility ascriptions. Journal of Risk Research, 25(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2021.1990111

- Hailemariam, A., & Ivanovski, K. (2021). The impact of geopolitical risk on tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(22), 3134–3140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1876644

- Hamzah, A. (2022, December 18). Changi Airport’s weekly passenger traffic hits 75% of pre-pandemic level. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/changi-airport-recovers-to-75-of-average-weekly-passengers-pre-pandemic

- He, H., & Cai, J. (2022, December 15). Covid-weary Chinese millionaires eye Singapore amid ‘chaos and unpredictability’ at home. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3203309/covid-weary-chinese-millionaires-eye-singapore-amid-chaos-and-unpredictability-home

- Heng, P. (2018, August 29). Are China’s gifts a blessing or a curse for Cambodia? East Asia Forum.

- Hin, P. (2022a, August 22). Digital literacy key to post-Covid rebound for tourism sector: Khon. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hin, P. (2022b, November 21). Eco-tourism key to post-Covid recovery. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hin, P. (2022c, November 2). Int’l tourism focuses unveiled. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hin, P. (2022d, November 27). New five-star hotel set for S’ville. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hin, P. (2022e, September 11). Regional travellers driving local tourism sector. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hin, P. (2023, January 3). No additional covid rules for arrivals from China: PM. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hom, P. (2022a, July 12). H1 int’l arrivals 51% of 2022 target. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hom, P. (2022b, June 29). Pros outweigh cons in plan to transform Preah Sihanouk: Study. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hom, P. (2022c, August 18). Special tourism policy’ will attract long-stay tourists: Sinan. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hom, P. (2022d, August 7). ‘Special tourist policy’ afoot. Phnom Penh Post.

- Hom, P. (2022e, May 17). Tourism co-financing scheme launched. Phnom Penh Post, Posted on May, 17 2022.

- Hor, K. (2018, February 23). As business and tourism ties strengthen, Chinese media make strides in Cambodia. Phnom Penh Post.

- Huang, Y. (2022). Consuming geopolitics and feeling maritime territoriality: The case of China’s patriotic tourism in the South China Sea. Political Geography, 98, 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102669

- Jaafar, F. (2022). Malaysia-china agree to foster stronger ties under BRI. The Malaysian Reserve. https://themalaysianreserve.com/2022/07/13/malaysia-china-agree-to-foster-stronger-ties-under-bri/

- Johnson, P. C., Xu, H., & Arlt, W. G. (2017). Outbound Chinese tourism: Looking back and looking forward. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1505098

- Kana, G. (2022, April 13). Malaysia needs Chinese tourists to lift economy. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2022/04/13/malaysia-needs-chinese-tourists-to-lift-economy

- Kouth, S. C. (2019, July 30). Preah Sihanouk governor cracks down on illegal signage. Phnom Penh Post.

- Lee, L. (2023, February 5). ‘We are always only aligned to one country — Singapore’: Shanmugam on need to put national interest first amid global challenges. https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/we-are-always-only-aligned-one-country-singapore-shanmugam-need-put-national-interest-first-amid-global-challenges-2101246

- Lew, L. (2022, February 22). Singapore Vs. Hong Kong: Covid Strategies Push Rivals Further Apart. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-22/singapore-is-winning-in-hong-kong-s-all-out-fight-against-covid

- Long, F., & Ooi, C.-S. (2022). Sustainability and the tourist wall: The case of hindered interaction between Chinese visitors with Malaysian society. In A. Selvaranee Balasingam & Y. Ma (Eds.), Asian tourism sustainability. Perspectives on Asian tourism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5264-6_5

- Malay Mail. (2022, August 29). Tourism minister sets new target of 9.2 million tourist arrivals this year. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2022/08/29/tourism-minister-sets-new-target-of-92-million-tourist-arrivals-this-year/25339

- MIDA. (2022). China, Malaysia economic and trade cooperation reach new highs. https://www.mida.gov.my/mida-news/china-malaysia-economic-and-trade-cooperation-reach-new-highs/

- MITI. (2023). Malaysia external trade statistics: Trade performance for year 2022 and December 2022. https://www.miti.gov.my/miti/resources/Trade%20Performance%20Media/Trade_Performance_Press_Release_December_2022.pdf

- MOF. (2021). Budget 2022: Seven Key Initiatives to Revive Tourism Sector. https://www.mof.gov.my/portal/en/news/press-citations/budget-2022-seven-key-initiatives-to-revive-tourism-sector

- Mosedale, J. (2016). Neoliberalsim and the political economy of tourism: Projects, discourses and practices. In J. Mosedale (Ed.), Neoliberalsim and the political economy of tourism (pp. 157–166). Routledge.

- MOTAC. (2020). National Tourism Policy 2020-2030. https://www.tourism.gov.my/files/uploads/Executive_Summary.pdf

- MoT Ministry of Tourism. (2020). Tourism statistics report, December 2020. National Institute of Tourism. Tourism Statistics Department. Phnom Penh.

- MoT Ministry of Tourism. (2022). Tourism statistics report, August 2022. National Institute of Tourism. Tourism Statistics Department. Phnom Penh.

- O’Byrne, B. (2018). Spike in Chinese visitors drives tourism boom. Phnom Penh Post, Posted on January 25, 2018.

- Ong, C. E., & du Cross, H. (2012). THE POST-MAO GAZES. Chinese Backpackers in Macau Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.08.004

- Ong, C. E., Ormond, M., & Sulianti, D. (2017). Performing ‘chinese-ness’ in Singkawang: Diasporic moorings, festivals and tourism. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12149

- Pearce, D. G. (1993). Comparative studies in tourism research. In R. Butler & D. Pearce (Eds.), Tourism research: Critiques and challenges (pp. 113–134). Routledge.

- Potter, W. J., & Riddle, K. (2007). A content analysis of the media effects literature. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400107

- Roberts, S. (2021). Media literature review guide: How to conduct a literature review of news sources. Simon Fraser University. https://www.lib.sfu.ca/help/research%02assistance/format-type/primary-sources/media-literature-review

- Shelley, B., Ooi, C. S., & Brown, N. (2019). Playful learning? An extreme comparison of the Children’s University in Malaysia and in Australia. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 2(1), 16–23.

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2011). Conceptualising policy: Technologies of governance and the politics of visibility. In C. Shore, S. Wright, & D. Pero (Eds.), Policy worlds: Anthropology and the analysis of contemporary power. Berghahn Books.

- Singapore Airlines. (2022). SIA Group Steps Up East Asia Services to Meet Strong Demand. https://www.singaporeair.com/en_UK/sg/media-centre/press-release/article/?q=en_UK/2022/October-December/ne0722-221003

- Singapore Tourism Board. (2019). Third Consecutive Year of Growth for Singapore Tourism Sector in 2018. https://www.stb.gov.sg/content/stb/en/media-centre/media-releases/third-consecutive-year-of-growth-for-singapore-tourism-sector-in-2018

- Singstat. (2022). Department of Statistics Singapore. https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M810001

- Sok, K. (2019, May 18). In Cambodia, the BRI must benefit locals too. East Asia Forum.

- Sokolíčková, Z. (2021). The Chinese Riddle. Tourism, China, and Svalbard. In Y.-S. Lee (Ed.), Asian mobilities consumption in a changing Arctic (pp. 141–154). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003039518-11

- Solhi, F. (2021, October 7). Malaysia estimates RM165bil in losses from tourist expenditure this year. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2021/10/734463/malaysia-estimates-rm165bil-losses-tourist-expenditure-year

- Sorn, S. (2019, February 1). Chinese tourists soar to 2M. Phnom Penh Post.

- STAN. (2022). Singapore Tourism Analytics Network. Singapore Tourism Board. https://stan.stb.gov.sg/

- The Star. (2022a, October 7) Budget 2023: Discounts, vouchers and rebates to boost domestic tourism. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/10/07/budget-2023-discounts-vouchers-and-rebates-to-boost-domestic-tourism

- The Star. (2022b, October 22). Start preparing for visitor arrivals from China, tourism players advised. https://www.thestar.com.my/metro/metro-news/2022/10/22/start-preparing-for-visitor-arrivals-from-china-tourism-players-advised

- The Star. (2023, January 25). China reopening a boost for Malaysian economy. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2023/01/25/china-reopening-a-boost-for-malaysian-economy

- STB. (2022). Singapore Tourism Board Annual Report 2020-2021: A year of rediscoveries and reimaginations. Singapore Tourism Board. https://www.stb.gov.sg/content/dam/stb/documents/annualreports/STB_AR_20_21.pdf

- The Strait Times. (2018, October 9). Chinese tourist arrivals to Malaysia plunge during Golden week. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/chinese-tourist-arrivals-to-malaysia-plunge-during-golden-week

- Su, X., & Li, C. (2021). Bordering dynamics and the geopolitics of cross-border tourism between China and Myanmar. Political Geography, 86, 102372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102372

- Tourism Malaysia. (2022). Arrivals by country. http://mytourismdata.tourism.gov.my/?page_id=232#!range=year&from=2016&to=2022&type=55876201563fe,558762c48155c&destination=34MY&origin=32CN,34ID,34SG

- UNWTO. (2021). International tourism highlights, 2020 Edition. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284422456

- Wong, K., Daud, S., & Lay, B. (2020). Full Transcript of 25-Minute Leaked Audio Recording of Chan Chun Sing Dialogue with SCCCI. Mothership. https://mothership.sg/2020/02/chan-chun-sing-leaked-transcript/

- World Bank Group. (2017). Cambodia Economic Update. Cambodia Climbing Up The Manufacturing Value Chain. Selected Issue: Cambodia Calling: Maximizing tourism potential

- WTTC. (2018, March). Travel & tourism economic impact 2018. Cambodia. World Travel & Tourism Council.

- WTTC. (2020). Travel & tourism economic impact 2020. Cambodia. World Travel & Tourism Council. March, 2018

- WTTC. (2022, March). Travel & tourism economic impact 2022. World Travel & Tourism Council.

- Xinhua. (2019, May 10). Chinese tourists to Cambodia continue to rise in Q1. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-05/10/c_138048788.htm

- Xinhua. (2020, January 19). China, Malaysia kick off culture and tourism year. Xinhua News.

- Xu, H., Wang, K., & Song, Y. M. (2020). Chinese outbound tourism and soft power. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1505105