ABSTRACT

Resilience is instrumental in understanding the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in colonised countries. Investigator-driven, quantitative descriptive studies can limit capacity for Indigenous people to “talk back” to the research process with their own perspectives of wellbeing and resilience. A Human Development and Capabilities approach can elicit self-determining definitions of wellbeing. This study presents findings from qualitative life history interviews of the self-defined health trajectories from a group of 11 Indigenous adults living in an Australian urban setting. In contrast to the prevailing deficit discourse, interviewees spoke about their strength and resilience. Common areas of health and wellbeing discussion such as socioeconomic disadvantage, family dysfunction, stress, problematic alcohol use and mental illness became transformed into narratives of never being without, the opportunity for upwards social mobility, the importance of family as positive role models and social support, abstinence, learning from past experiences and coping through challenges. Historical context, intergenerational trauma and racism impact wellbeing, yet are often not measured in large quantitative studies. Findings support affirmative action initiatives to reduce socioeconomic disadvantage to improve wellbeing. Narrative-based capability approaches provide contextualisation to how Indigenous people navigate through significant life events to maintain wellbeing.

1. Introduction

International literature defines resilience as the dynamic ability to negotiate through tensions to support wellbeing, using the strengths and resources available in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar Citation2008). Resilience is instrumental in understanding the wellness of Indigenous peoples in colonised countries (Andersson and Ledogar Citation2008; Kirmayer et al. Citation2011). It encompasses “interactions between individuals, their communities, and the larger regional, national, and global systems that locate and sustain [I]ndigenous agency and identity” (Kirmayer et al. Citation2011, 84). This interconnects with an Aboriginal worldview of health and wellbeing, a “whole of life” approach, that incorporates the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the community, not just an individual (NAHSWP Citation1989). Social and emotional wellbeing is not just the absence of a mental disorder. As posited by Holland et al., “a positive state of mental health and happiness associated with a strong and sustaining cultural identity, community and family life—has been, and remains, a source of strength against adversity, poverty and neglect” (Holland, Dudgeon, and Milroy Citation2013, 2).

Despite previous calls for more research into the wellbeing, strength and resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Australian Indigenous) people, this area is not well-examined in the literature or in broader public discourse in Australia (Bond Citation2005; Brough Citation2001; HREOC Citation1997; Priest et al. Citation2009; RCIADIC Citation1991; Swan and Raphael Citation2006; Ypinazar et al. Citation2007).

Since the 1970s, Australian public health studies have documented the inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (Brough Citation2001). This has been reinforced by a decade of national government policy focus on “Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage”—and attempts to improve government-selected targets across life expectancy, child mortality, early child education, literacy and numeracy, educational attainment, and employment (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2020). Closing the Gap policy targets, as Jordan and colleagues argued (Citation2010, 340), “are focused purely on measuring gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians on a pre-determined set of mainstream socio-economic indicators.” Indigenous people are now increasingly becoming known by these powerful descriptors of disease and social disadvantage (Stoneham, Goodman, and Daube Citation2014), tacitly reinforcing a discourse of deficit and pathology in imaginings of Indigenous people in Australia (Bond Citation2005; Moreton-Robinson Citation2009). Bond and Singh (Citation2020, 1) note “Closing the Gap tends to focus our attention disproportionately on the behaviour of individuals, suggesting that health inequalities are a product of Indigenous lack, morally and intellectually, rather than socially determined.” Similarly, Biddle (Citation2014, 715) argues the targets “do not sufficiently encapsulate the range of wellbeing measures identified as being important to Indigenous Australians” yet remain as the dominant discourse. This begs the question, then, for whom are these indicators? (Biddle Citation2014). Statistical equity does not necessarily equate to wellbeing; thus, alternative methodological approaches are needed to explore the interrelated complexities of Indigenous health and wellbeing.

The dominance of descriptive quantitative health studies to explore Indigenous wellbeing in Australia has limited the capacity to provide context to dynamic and subjective experiences of wellbeing and resilience over the life course (Priest et al. Citation2009; Walter Citation2010; Ypinazar et al. Citation2007). The backdrop of ongoing structural oppression, colonisation and intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous people in Australia is often absent from discussions in large descriptive quantitative studies, despite the causal influence of these inequalities over the life course (Sherwood Citation2013). Beyond aggregated data using Indigenous status, the voices of Indigenous people are rarely privileged within public health. Indigenous scholars have argued that this has led to a disjuncture between public perceptions of Indigenous illness and dysfunction, and the perceptions of resilience, strength and capabilities that Indigenous people express within their own lives (Bond Citation2005; Fredericks Citation2010). As noted by an Indigenous participant in a previous Australian study, “I don’t think that story gets told enough, you know, we don’t talk about all the well families” (Priest et al. Citation2009, 189). There has also been limited consideration of the positive impact of Indigenous cultures on wellbeing (Biddle and Swee Citation2012; Biddle Citation2014; Jones, Thurber, and Chapman Citation2018). In addition, few Australian Indigenous health studies have an urban focus (Waugh and Mackenzie Citation2011; Martin et al. Citation2019); previous research has primarily focused on the rural and remote setting (Eades et al. Citation2010; Priest et al. Citation2009), despite most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now living in cities (AIHW Citation2015).

Human development and capability approaches are increasingly being recognised as useful in conceptualising Indigenous wellbeing with self-determination (Durie Citation1994, Citation1998; Maaka and Andersen Citation2006; Smith Citation1999; Ten Fingers Citation2005; Yap and Yu Citation2016). They align with the United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, which states that Indigenous people must be agents of their own development and have the right to self-determine their wellbeing (United Nations General Assembly Citation2007). Human development and capability approaches support choice and empowerment of people to achieve outcomes they value within the opportunities available to them (Bockstael and Watene Citation2016, 266). This is synergistic with the concept of resilience, the ability to negotiate through circumstances to maintain wellbeing in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar Citation2008). This contrasts pre-imposed outcomes on or for people, such as the Closing the Gap targets (Vaughan Citation2011), subjective measures (e.g. happiness) and markers of material wellbeing (e.g. income) (Robeyns Citation2011). Whilst Nussbaum (Citation2011) considered ten central capabilities as being essential and universal, Sen’s (Citation1999) encouragement of a pluralism of capabilities is better suited to this study as it accommodates for flexibility and cultural differences, allowing people to define their own meanings of wellbeing (Jordan, Bulloch, and Buchanan Citation2010; Yap and Yu Citation2016). Sen’s capability approach recognises that structural barriers, such as institutionalised racism, intergenerational trauma and socio-economic challenges, can prevent or hinder people’s capability or freedom, throughout their lives, to achieve their chosen subjective functionings—“the various things people value doing or being” (Sen Citation1999, 75). Put simply, it focuses on the intersection of what you want to do with your life with the constraints of the opportunities afforded to you—a phenomenon acutely familiar to oppressed peoples around the world.

It is within this context that this study explores the resilience of Indigenous people to maintain their wellbeing in spite of significant structural barriers. By privileging participant voices through the use of a Capability approach, this paper describes how the Aboriginal people interviewed, who were living in an Australian urban setting, defined their own wellbeing and how they transformed the resources they had into achieving the type of wellbeing they value.

2. Methods

This study draws on qualitative data from life history interviews conducted with a small group of Aboriginal people who were part of an existing birth cohort study based in a predominantly urban setting in Australia. This data was collected as part of a broader study with a unique opportunity to triangulate qualitative life narratives with the existing longitudinal quantitative data collected from pregnancy and birth to young adulthood. Whilst some quantitative data is presented for comparative purposes (see Box 1, and ), the current study focuses on the qualitative narratives that emerged from these interviews to emphasise the participants’ own reflections of their health, wellbeing and resilience trajectories.

For comparative purposes, and present a selection of MUSP quantitative data from the eleven people who completed the qualitative life history interviews. It follows the common epidemiological practice of presenting prevalence of ‘risk factors’ from the early life course, e.g. poverty and incomplete schooling (though low numbers prevent meaningful statistical testing). As with all descriptive point estimate statistics, the data presented in and cannot provide any detail about the context, severity, impact or meaning of these factors on the lives and wellbeing of the people interviewed.

Table 1. Employment, homeownership and educational attainment of interviewees compared to national Australian data.

Table 2. Comparison of family income and maternal educational attainment at baseline for interviewees and all Mater-University Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) participants.

2.1. Study Sample

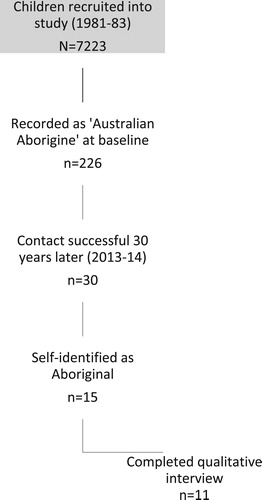

Interviewees were recruited from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) (Najman et al. Citation2005). From the original sample (n = 7223), 226 study infants had been identified as having at least one parent who had been identified as “Australian Aborigine” at baseline (1981–1983).Footnote1 From this group, 30 participants were able to be contacted some 30 years later, with 15 self-identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (). Rather than this discrepancy in Indigenous identification being due to personal decisions not to identify, it was found to be partly explained by miscodes and the problematic way group membership had been originally collected over 30 years ago (Hickey Citation2015). The data presented in this paper corresponds to 11 of the 15 people who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander three decades later and completed the qualitative interview.Footnote2 Sampling was saturated when all eligible participants had been contacted and invited to participate. In total, five men and six women, aged 31–34 years and currently living in Australian cities, were interviewed.

2.2. Theoretical Approach

Influenced by a Western-based social constructivist epistemology and interpretivist theoretical framework, this study acknowledges that meanings and interpretations of the social world are constructed reiteratively through highly contextualised social interaction (Crotty Citation1998). The research context itself can influence and be influenced by interviewee and interviewer rapport and backgrounds (Pezalla, Pettigrew, and Miller-Day Citation2012). This study formed part of the author’s doctoral project. The author is a white Australian (non-Indigenous) woman with a professional background in sociology and public health, and an experienced interviewer with no prior relationship with the participants. Given the author conducted and analysed the qualitative interviews herself, steps were taken to be a reflective practitioner (Mason Citation1996, 164–165), such as keeping a reflective journal (Nadin and Cassell Citation2006) and having regular discussions with an Aboriginal supervisor to ensure that findings reflected the needs and experiences of Aboriginal people.

2.3. Method Choice

Life narratives can be a powerful approach for understanding the subjective experiences of health and wellbeing trajectories (Pals and McAdams Citation2004). Qualitative life story interviews were used in this study to gain a deeper understanding of the way the social context can influence wellbeing for Indigenous people in an urban setting over the life course. As noted by Yap and Yu (Citation2016, 317):

A significant component of exercising Indigenous self-determination stems from the transformation of the power relations embodied in current research paradigms. Research paradigms and associated methodologies need to privilege Indigenous ways of knowing and ensure that Indigenous peoples, as collaborators and not as “research subjects”, fully and meaningfully participate in the research process to co-produce knowledge according to Indigenous worldviews.

Qualitative interviews are, arguably, a more culturally responsive way of information gathering with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than quantitative surveys; they can empower marginalised voices by allowing the interviewee to guide the conversation rather than the researcher having a structured preconceived research agenda (Vicary and Bishop Citation2005). Semi-structured short life history qualitative interviews (Atkinson Citation2004) were chosen to allow flexibility for interviewees to provide a narrative of their own lives from their perspectives.

Life history interviews centre on the subjective life experience, “what the person remembers of it and what he or she wants others to know of it, usually as a result of a guided interview by another” (Atkinson Citation2004). Taking a subjective life course approach allows for greater exploration of the dynamic processes that inform one’s self-perceived wellbeing. A short life history interview is typically shorter in length than a traditional life story interview and is more focused in discussion (Atkinson Citation2004). In this study, interviewees were prompted and focused on “what influenced your health and wellbeing throughout childhood, adolescence and adulthood and what keeps you strong.”

2.4. Data Collection

Potential participants were sent an initial letter about the qualitative study and were followed up by telephone. Interested individuals were sent a detailed information sheet and consent form, with informed consent obtained before commencing the interviews. Participation was voluntary and confidential, and participants were free to withdraw at any time without penalty. Interviews were conducted over the phone or in person between June 2013 and March 2014, lasting approximately one hour (ranging from 1 to 2.5 hours). Interviewees were reimbursed with an AU$25 voucher for their time. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with participant pseudonyms added. Some details have been removed to maintain interviewee anonymity and minor edits made for readability. Ethical approval was obtained by the Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review committee at the University of Queensland.

2.5. Data Analysis

Life history excerpts were chosen that could best “talk back” to commonly used social determinants for Aboriginal health and wellbeing (Biddle Citation2014). These included socioeconomic status, family, mental health and alcohol use (c.f. AIHW Citation2015), with the addition of connection to community and culture, and the impact of forcible removals, as these were identified as being important to the interviewees (see also Biddle and Swee Citation2012; Dockery Citation2010; Jones, Thurber, and Chapman Citation2018). Developmental explanatory logic was used to analyse how social processes in the interviewees’ wellbeing narratives evolved over time, with comparative thematic analysis being used to compare similarities and differences between the life histories (Mason Citation1996, 137). Data was organised using QSR International’s NVivo 10 software, and an audit trail (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985) was used to document changes, with emergent themes discussed with supervisors. Like all retrospective interview-based studies, self-reporting is likely to underreport negative behaviours, and invoke memory bias with post-hoc rationalisation (Reith and Dobbie Citation2011). However, this meaning-making and subjective experiences of health and wellbeing were considered important to this study. The social factors explored in the present study are not an exhaustive list; the significant influence of racism and racialisation on wellbeing among this group are presented elsewhere (Hickey Citation2016). On the whole, the richness of data and flexibility of the qualitative interviews allowed space to prioritise the voices of the Indigenous people interviewed and these narratives of resilience and wellbeing that were considered important to them.

3. Results

3.1. Self-Defined Health Trajectories

Within the context of their life narratives, the eleven Indigenous people interviewed described a comprehensive and dynamic understanding of what it meant to “be healthy.” Interviewees drew threads between social determinants of health and how these influenced wellbeing over the course of their lives:

It’s, I guess, everything. It’s being well enough to function and do all your normal everyday stuff but also going home to a happy well family, eating well, having enough money to have enough money to survive and not struggle. (Sarah)

Interviewees ubiquitously described their health trajectories via changes across social determinants of health with an emphasis on their resilience journeys. Rather than focusing on the challenges in their lives, interviewees chose to focus on the strengths and achievements in overcoming these hardships.

3.2. Socioeconomic Factors: Income, Education, Employment and Homeownership

Five of the seven Closing the Gap targets focus on individualised education and employment measures as a way to track “Indigenous disadvantage” (i.e. early education and school attendance, literacy and numeracy, completion of high school and employment) (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2020). shows that interviewees in this study were more likely to be currently employed and to have completed secondary or higher education than other Indigenous people nationally (AIHW Citation2015). Differences in current socioeconomic factors for this group may be reflective of attrition bias, as participants with lower educational attainment (including lower maternal educational attainment) and lower family income at baseline were more likely to be lost to follow-up in the longitudinal study (; see also Najman et al. Citation2005). Interviewees were also found to be more likely to have experienced family poverty at baseline than other MUSP participants ().

When discussing socioeconomic influences in their lives, however, interviewees resisted employing a discourse of disadvantage. While all the interviewees described themselves and the parents in their life narratives as coming from typically working class backgrounds, it was stressed that, “No matter what, there was always food on the table, there was always clothes on ya back and there was always hot water running. With a roof over your head” (Millie). Joshua explained that, “We were never rich or anything but we were never in want of anything.” Steve said, “We didn’t grow up with lots of stuff so I grew to appreciate it when I got my own money and paid my own way in life.” Interviewees did not use a discourse of disadvantage to describe their lives and instead focused on their families always providing for each other where it counts. All interviewees described their parents as hardworking, with at least one parent being employed when interviewees were growing up, suggesting that low family income was reflective of systematic discrimination of the low wages earned by Indigenous people.

In the interviews, the concept of education was not limited to completed schooling as is often used in descriptive quantitative studies. In discussing the levels of education of his parents, Isaac emphasised that while his parents may not have had much formal education, his parents had encouraged learning through informal ways, such as taking road trips to historical sites. This played a significant role in Isaac’s life:

I think [my dad] may have had the equivalent of a primary school education with maybe a little bit of high school education, but not much. He’s basically entirely self-taught … My mother dropped out [before finishing high school] … But she’s always gone back and done different studying courses. So education’s always remained throughout her life. As for Dad, well, he always studied. He has a huge library of literature. He’s always pursuing knowledge … I guess that’s what always kept my academic interest.

Parents had stressed the importance of education for their children, with many of the interviewees’ parents not completing high school themselves. For example, Hayley said:

I was always pressured to achieve and be very successful at whatever I did … My parents were like “We didn’t succeed so we’re going to try and push you to”.

As adults, the interviewees’ narratives revealed a gradual process of upward social mobility, for some this was enabled by increasing opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. At the time of interview, nine interviewees had completed year 12, and all interviewees went on to complete post-secondary qualifications from Training and Further Education (TAFE) institutions and/or university. Ten were currently employed (eight full-time, two part-time, and one a self-employed business owner), and only one interviewee reported being temporarily “in-between jobs” and was currently studying. Some interviewees referred to an almost serendipitous pathway by which they entered employment or education, as part of recruitment strategies by institutions to redress Indigenous disadvantage:

I did some TAFE certificate [during senior high school]. And then I started a Diploma of [removed] at TAFE. But I only did a week of that, cos I got a call to come and do [an Indigenous] traineeship, so I cancelled my TAFE. I got an Indigenous traineeship with the [public service] and I’ve been here ever since. (Lauren)

*

I actually got into uni through the alternate entry through the Indigenous unit. At the end of high school, I wasn’t even planning of going to uni. I was planning on a career in a trade, like carpentry, because I did manual arts at high school. Then at the end of high school, in English [class], they made everyone apply to university. (Joshua)

Removing some barriers to access through these specialised recruitment strategies enabled interviewees to gain early study and employment opportunities after school that may not have been accessible otherwise. However, not all interviewees obtained positions through such strategies. Chris described his excitement upon receiving his position:

Yeah, probably my biggest [life turning point] was getting the job I did. Because maybe there’s I think 10 positions available and maybe 2000 applicants. It was the job I wanted my whole life and finally got it.

It was not uncommon for participants to report returning to study later in life or expressing an interest in doing so. Two were currently studying undergraduate degrees and two postgraduate. Interviewees who had completed an apprenticeship or other TAFE qualifications spoke about going to university within the next five years: “I’m thinking of going to uni to improve myself. It’s the next level of my trade” (Steve). Isaac, who was a self-employed business owner said:

I have this goal in my mid-thirties to do an MBA. Basically, I want to get myself in a position where I have the paperwork to go along with what I’m achieving in my businesses and things like that. So that I can actually be board member material in my late thirties, early forties.

Enabled by gainful employment, homeownership was considered an important and attainable aspiration amongst this group. Three participants currently owned their own home, with a further four expressing an interest in buying a home within the next five years.

Everything’s going great. I wanted to buy a house at 21. That was one of my goals. But I didn’t, it ended up being [in my mid twenties], but … We have bought a house, and we’re planning on buying another one in a few years. (Lauren)

3.3. Family and Role Models

Interviewees emphasised that experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage or being exposed to life stress did not make families bereft of strength and capabilities. Family was consistently described as the primary source of strength, social and emotional support, and as one of the important contributors to their wellbeing. Many of the interviewees cited their parents as role models. There was an acknowledgement of hardships and challenges their parents endured, with an emphasis on how they were overcome. For example, Rebecca explained:

When I was at school my mother, ah, went a little crazy? She had bipolar and was undiagnosed. At times it was hectic as hell … It was pretty hard … But we didn’t go anywhere. Dad didn’t go anywhere. Yeah, nah, he’s like let’s get this sorted. Got her on medication. And they are still happy married, what like, thirty years later.

Not only was Rebecca’s family looking out for one another, they also had the capacity to take on “a criminal street kid living with us for a few years. We made him go on the straight and narrow, so that’s great.” Rebecca also spoke of her parents as teenagers raising her father’s younger siblings when his father died prematurely, “He wasn’t the eldest at the time. He was just the responsible one.”

Lauren also described her mother’s life challenges through a discourse of strength, in spite of experiencing adversity:

My mum had me when she was [very young] … She showed me that it doesn’t matter what had happened in your life. I mean, she was a victim of domestic violence … We seen that happen to her. We’ve seen beer bottles. We’ve seen her getting punched. We see everything. And for her to come out of that, and for her to be strong, and show us that it doesn’t matter what happens to you, that you can still overcome these things and achieve whatever you want. That’s what I really love.

Similarly, Jordan said:

I always had my father being the best role model I ever had … I think just the amount of adversity he’s had growing up. And the fact that he’s gotten through it, is pretty inspirational … He affects other young men in his life on how they look and see things. Dad’s got strong discipline … These guys, as they get older, still look to him for inspiration, I guess, on how to have a good successful life and beat the odds on where they come from and achieve success.

While parents were regarded as the primary caregivers and sources of support, for some grandparents, aunties and uncles “were always there to help” (Millie), particularly for single parents or those experiencing troubles at home. When Jessica’s parents split up and her mother remarried an abusive man during Jessica’s teenage years, her Grandmother became her “rock.”

Whenever interviewees discussed hardships, whether in their lives or in the lives of others, this was always countered by narratives of strength and perseverance, focusing on the positive aspects and overcoming difficulties.

3.4. Impact of Forcible Removals

The effect of historical government policy on Indigenous families was an important area for consideration among the interviewees, despite not previously being documented in the MUSP. Considering the important role family plays in upbringing and wellbeing, the intergenerational impact of the Stolen Generations (past government forcible removal of children from their families, land and culture; HREOC Citation1997) was discussed with these interviewees. While none of the interviewees had been forcibly removed themselves, seven out of eleven reported that a family member (mainly grandparents) had been “taken away” (note: two said no, two were unsure), and interviewees continued to identify with the mission/reserve communities where family members had been relocated.

For those whose grandparents had grown up in foster care or in the dormitories of Aboriginal missions/reserve communities, their parents had moved to Brisbane in young adulthood for job opportunities. Among those who had family members separated, reconnecting with these individuals was an important part of ensuring family wellbeing, with families making extensive efforts to reconnect: “Mum’s done a lot of work trying to trace family, so I can’t remember if Mum found her or if it was the other way around” (Sarah). While some interviewees knew from an early age, many had only found out that family members had been taken away later in life as it was something not often talked about among the families, despite having an ongoing influence on family wellbeing. Hayley, whose great-grandmother and grandmother had both been part of the Stolen Generations, described what it was like finding out “not so long ago” after a “fair bit of investigating”:

I was sad. But it also explained a lot of my grandmother’s behavioural traits, insecurities and other things that had happened to her and then her subsequent raising of my father. Looking at it now, I can identify a lot of the reasons and things that they were brought up the way they were, with different insecurities or emotional behaviours they have developed from that. We do have a strong sense of family but in the same sense of that it’s not particularly strong. We’re not a very connected family, I guess, which is disappointing for me because I think we should be. But we’re not.

While no members of Isaac’s family were removed, government removals still had an impact on his family’s wellbeing:

I think that’s part of where the mental health issues come from. There was always this fear that they were going to be taken. Other kids around them, their families had had issues. But [my mum’s family] managed to survive through intact as a family. Which was quite significant, I think. They had … White farmers who really looked after my mum’s family and made sure that things were done for them, or supported to keep them intact and to keep all the girls and everybody at school … [Mum] grew up in a rural area … They basically lived on a block in a tin hut with a dirt floor. That was her childhood. They eventually moved into town when I think she was in her high school years … From what I know, all of the issues stem from their childhood and the issues they had to deal with. It was a very different time, that’s for sure.

These narratives suggest the importance of the socio-historical context and impact of government policy on the wellbeing of Indigenous families that is not readily captured in large mainstream quantitative studies. This suggests the ongoing legacy of intergenerational trauma that must be considered by public health researchers and practitioners alike.

3.5. Connection to Community and Culture

Interviewees reflected on their diverse connections to community, history and culture as an important part of their life histories and wellbeing. This remains largely absent from discussions in public health research and was not reflected in Australia’s mainstream narratives. Jordan said:

At school, I would have liked to see talked about just the whole interaction between colonisation of Australia and the way that whole process went through 1900s, I guess, all the way up til modern day. And to give Australians an idea of what actually happened. So many people today, who just are kinda clueless on it. You have these preconceived notions that are wildly incorrect.

Engaging with the Aboriginal community played a key role for some interviewees in maintaining a connection to their Aboriginality and cultural wellbeing. Lauren said that as children, “we used to go in and talk to the Elders as well. And, you know, get a bit more history and a bit more stories that they had to tell from when they were growing up.” Jordan said:

We’d go back to [a particular former reserve/mission community] and see family and do some community stuff out there. […] My grandmother was an Elder [at that former reserve/mission community]. So my family’s still got quite a bit of a standing over there, in that community.

Another point of connection to community and culture was through Indigenous-identified positions within the public service, with four participants working across fields of cultural heritage, transport, justice and health. Roles included research, liaison or developing policies and procedures when working with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people:

It can be challenging, at times. But I do find it rewarding. I enjoy mixing with our people. I really love that. I enjoy going out to communities. I’d never been to the remote communities before I came to this job … I’ve been to the places where, you know, where people were removed from their lives and families and moved to these missions, and discrete communities because of the government policies in place then. So it’s really good to get more history about what Australia was like back then, and this job really helps me do that. (Lauren)

Current involvement with the Aboriginal community played an important role in the lives of many of the interviewees. Similar to reports from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (ABS Citation2010), types of community activities included:

visiting extended family

visiting a former mission/reserve community

attending sorry business/funerals

celebrating National Aboriginal and Islanders Day Observance Committee (NAIDOC) week activities

sitting on the board of Indigenous organisations

teaching Aboriginal dance, language and stories

playing for an Indigenous sports club

attending events such as Indigenous awards ceremonies, opening nights, and community barbecues

being involved in an Indigenous church ministry

attending veteran memorials, marches and political rallies

helping their child’s school plan cultural events

working in Indigenous identified positions

accessing Indigenous health or legal services.

All interviewees were currently engaged in several of these activities, even if they expressed feelings of not having much involvement with their community. Among those who reported less involvement, Chris explained he went to NAIDOC because:

[My employers] actually sponsor NAIDOC Week, so we go there, set up a stall and stuff […] at Musgrave Park. […] Besides the work commitments, that’s pretty much the extent of it.

Steve said, “Yeah, used to be involved in NAIDOC for a few years, before all the drunken people sorta moseyed along.” Interviewees who had children emphasised the importance of their children maintaining a connection to their Aboriginality and learning about their Aboriginal heritage through family and kin by attending NAIDOC celebrations or other community events. Rebecca said:

NAIDOC family fun day is next week. I make sure I take the day off work to go. I try to take my kids there every year. They are only [very young], but it’s still something they need to know. My partner’s White, so it’s something they need to know. (Rebecca)

This sentiment was expressed at times not just for their own children but for young Aboriginal people in general:

I’d obviously recommend particularly young Indigenous people or any young person today is if they feel a strong connection to culture is to get to the root of it without all the social and—I guess—what am I trying to say—without all that social stigma that comes along with history and the things that have happened. […] But if you can identify with your culture, then look at your family and look at what is really important to you then you can grow a lot from there. (Hayley)

3.6. Alcohol and Mental Health

The discursive practice of emphasising positive growth and learning from past experiences continued as interviewees described their health-related behaviours of alcohol use and mental health experiences. Again, the importance of one’s social context on the wellbeing trajectories was foregrounded. On her adolescent experience, Lauren said:

I did go off the rails a bit when I was [in my mid-teens]. So I did um, you know, pot, all that kind of stuff, tried that, sniffed glue … We’d go with my friends and drink without Mum knowing … Then I’d see my friends get in trouble with the police a lot. And I started to think I didn’t really want to go down that way. So I moved away from those friends. I didn’t hang around that friend any longer. Yeah, so [pause] I did go down paths where I thought I’d gone the wrong way, did a bit of stealing, but not much. Got in trouble with the police a couple of times, really nothing that I feel has impacted me today. I’ve learnt from those things, and I’ve learnt that I can be a good person anyway.

By their thirties, all interviewees reported they were happy and doing well. Among those who described having experienced challenges to their social and emotional wellbeing, their narratives suggested a correlation between problematic alcohol use, mental illness and increased life stressors. For example, Hayley explained:

My ex-husband was an alcoholic. There was often a stage where I’d just feel like, ‘Oh my God, I need a drink’, just to deal with things … [He] was aggressive towards me, a little bit of physically abusive as well and he had some substance issues. So that’s why I left him [a few] years ago. I used to have panic attacks. But I don’t get [them] anymore.

Jessica described a cyclical pattern of experiencing and overcoming significant hardships in earlier years, with substance use being a symptomatic reaction to external stressors that would challenge her social and emotional wellbeing:

I dropped out [of school] in [junior high school]. [Mum] remarried and her husband was an arsehole. [My home life was] always pretty crap. It was never perfect … We used to avoid going home as much as possible. We’d hang out at friend’s places, or go to the park, or go anywhere but home … I used to run away. Started drinking and stuff. And hanging out at the park … [I was in junior high school] when I left Mum … [A few years later] … me and my sister went off the rails together. So neither of us were working, we were drinking all the time, smoking all the time, taking pills all the time. And then I got hit by a car. So then I went to hospital. I was in a coma for [a few] weeks … I was told I’d never walk again, can’t speak … Yep, so I got myself out of hospital, said I’m sick of this, I can look after myself … I taught myself to walk and talk again, and met the next guy that I know and ended getting married to him. And then he beat me up … I was single again, back to drugs and alcohol again.

As an adult, Jessica now abstains completely from alcohol use and aspires to be a drug and alcohol counsellor because she says she has learnt so much from her own personal experience. She has found stability in her relationship with her current partner, reiterating the importance of family wellbeing on the individual.

As interviewees got older, they described their lives as becoming more stable, with stable employment and most of them in stable relationships. They also described an increased sense of responsibility, at home with children, or at work, as a protective factor against harmful alcohol use, with interviewees describing having made a conscious choice to give up or cut down (with two abstaining altogether). For example:

[I don’t drink much alcohol] these days. God, when I was [in my late teens], I did a good job! We’d go out every weekend and stuff but since I’ve had the kids, no. I’ve got to be a responsible adult. Someone’s gotta be! Even my partner barely drinks anymore. Don’t get me wrong, if we’re going out, we will, but if we’re just going to a barbeque or something, then no, not so much … I don’t get drunk, because you know, gotta deal with the hangover the next day and children … Does not work, at all! (Rebecca)

*

I was pretty much into getting hammered every other weekend, so on Saturdays after our football games … After I turned 21 and stopped playing football, that was pretty much the moment I stopped drinking heavily and saved up and bought a house. (Steve)

Giving up or reducing alcohol reflected a whole-of-life wellbeing approach, where interviewees were empowered to “take control” of their health, lifestyles, finances, wanting the best for their futures.

When asked about how they perceived their current health in general, interviewees unanimously replied that they were doing well and were happy with their lives, “I’d probably say I’m the healthiest I’ve been in a decade” (Steve). Hayley said, “I’m really enthusiastically healthy. I’m active. I’m happy. Yes, I’m holistically pretty good.” Isaac felt the need to add the following disclaimer at the end of his interview:

I think everything that you’ve listened to or taken down or recorded, has to be put into context that we were very, very lucky [pause] individuals … We had a super good upbringing, you know. Kids and families that didn’t have anywhere near what we had. Even though, you know, not financially, but life enrichment stuff. And like, yeah, I think it’s just a total reflection of that … That needs to be made very clear in context to other people’s reactions. We’re just very, very lucky, I guess … It’s not really luck, is it? Heh. Our parents are very good.

4. Discussion

This study has presented the self-defined wellbeing trajectories of a group of Indigenous adults in urban Australia. The resilience narratives that emerged challenge the ubiquitous representations of disadvantage and disease of Indigenous people commonly reported in large descriptive quantitative studies (Bond Citation2005; Brough Citation2001). Layering a human development and capability approach enabled interviewees to articulate their capabilities and how they transformed the resources and opportunities they did have into achieving wellbeing and a life they value. Furthermore, rather than focusing on pathology or Indigenous ‘lack’ typified by the Closing the Gap policy (Bond and Singh Citation2020), the Indigenous perspectives presented in the qualitative interviews emphasised the important influence of diverse social determinants of health. Interviewees used their agency to actively resist the discourse of disadvantage and while interviewees may have experienced financial hardship in childhood, they did not want this to define their lives; rather they wanted to be known for their strengths. Routine areas of inquiry for determinant of health such as socioeconomic disadvantage, family dysfunction, stress, problematic alcohol use and mental illness were transformed into narratives of never being without, the opportunity for upwards social mobility, the importance of family as positive role models and social support, abstinence, learning from past experiences and coping through challenges. The historical impact of government policy on the lives and wellbeing of Indigenous people is often absent from large health studies yet surviving through the generational impact of the Stolen Generations was perceived to have considerable importance to the wellbeing of Indigenous families. A connection to culture and community was also considered important to their wellbeing narratives, despite being absent from the policy discourse of Closing the Gap. Despite interviews being limited to one hour and primarily conducted over the phone, the qualitative life history interviews provided rich context to the dynamic social factors present in the lives and wellbeing of the participants. This study shows qualitative life stories are critically necessary in complementing and explaining one’s health trajectory, highlighting the need for strength-based, capability-focused life course understandings of wellbeing and resilience for Indigenous people in Australia.

4.1. Discursive Practices of Resilience Meaning-Making

Defining and measuring resilience is a subjective experience; tensions in knowledge production arise when we question whose knowledge and experience is privileged most. For example, Ivanitz’s (Citation2000, 49) proposition that “urban Aboriginal people think they are healthier than they actually are” (emphasis in original) prioritises the researcher as the “knower” of the Indigenous experience, over the individuals themselves. The conceptualisation of resilience in quantitative descriptive studies is tacitly limited to a low prevalence of risk factors chosen by the investigator. However, to the interviewees in this study, resilience was the ability to be satisfied across various life domains while maintaining strong social and emotional wellbeing, in culturally meaningful ways. Life narrative approaches provide opportunities for naturally occurring growth narratives (Pals and McAdams Citation2004). The discursive practice employed by the interviewees of following up a life detail or event that could be portrayed as negative with something positive may be part of how interviewees maintained a positive outlook on life. This heuristic device was conceptualised by Tomkins (Citation1987) as “limitation-remediation scripts,” whereby an individual narrates negative experience, seeking to remediate its impact to preserve positive affect (McAdams et al. Citation2001). Hausler, Golden, and Allen (Citation2006) argue this repositioning of perception in one’s life narrative may be part of the resilience process; through meaning-making, we make new actions, and in turn create new meanings, mediated through the researcher’s analysis and interpretation. It may also be in response to interviewees feeling a burden of representation within the research context, with concerns about how they will be perceived, and how Indigenous people may be portrayed in the research as a consequence. Moreton-Robinson (Citation2009, 63) argues that “patriarchal white sovereignty as a regime of power deploys a discourse of pathology as a means to subjugate and discipline Indigenous people to be extra good citizens,” following the neoliberal ideals that if you work hard, you will be accepted by mainstream society. Previous research, however, has demonstrated that this is not the case for Indigenous people; racism persists regardless of socio-economic factors (Hickey Citation2016). In these interviews, neoliberal individualised ideas of “success” such as completing higher levels of education, being employed, and being aspiring homeowners were present, though this was interwoven with a value on cultural and community wellbeing. The neoliberalising focus on individual indicators of ‘disadvantage’ in the Closing the Gap targets ignores how cultural connection and community wellbeing were seen as important functionings for Indigenous people in this study, as found elsewhere (e.g. Biddle and Swee Citation2012; Dockery Citation2010; Jones, Thurber, and Chapman Citation2018).

4.2. Enabling Resilient Trajectories: A Case for Affirmative Action

Sampling from an existing longitudinal study provided a group whose voices are not often heard within Indigenous health literature—Indigenous people with higher levels of education and employment living in an urban setting—despite being a growing demographic in Australia (Lahn Citation2013). The narratives suggested interviewees achieved this through the lessening of some structural barriers to education and employment through successful affirmative action initiatives such as Indigenous-specific recruitment strategies. Sen’s (Citation1999) view of development reflects the need to create an enabling environment for people to enjoy their lives.

In this study, systematic racism curtailed freedom but interviewees chose to strive for the ‘good life’ (Sen Citation1999), within the resources they do have, to still achieve wellbeing they value. This has important implications for policy development as a way to redress socioeconomic disadvantage, creating opportunities that may otherwise be unavailable due to structural discrimination—something that is often oversimplified in the Closing the Gap rhetoric. The Indigenous-specific education and employment strategies described in the current study may alleviate some of these structural barriers, giving opportunities for many interviewees to do well in their careers and, by proxy, enhance their lives and wellbeing trajectories. Though the higher levels of education and employment among this group did not make the Indigenous people interviewed immune to challenges to social and emotional wellbeing, having stable employment and housing—and social support—did appear to absorb some of the impact of life stressors. Previous studies have also found that cultural connection increased wellbeing, and educational attainment and employment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Biddle and Swee Citation2012; Dockery Citation2010), as well as the importance of connection to Country (ancestral lands), including nature and ecology, to the wellbeing of Indigenous peoples (Sangha et al. Citation2015). This supports the need for more research into the relationship between culture, Country and wellbeing, such as the Mayi Kuwayu study (Jones, Thurber, and Chapman Citation2018), to inform community based programs and policy initiatives. The findings from the current study highlight the importance of using qualitative narrative methods to elicit the interconnected and dynamic aspects of Indigenous peoples’ lives to understand pathways to wellbeing. This study also affirms the need for more strengths-based, capability-focused research to capture the already existing resilience and aspirations of Australia’s Indigenous community who continue to experience significant structural barriers today.

5. Conclusion

Study objectives and methods can influence the way social phenomena and health trajectories are interpreted in research. Qualitative life history methods that privilege the voices of Indigenous people can facilitate understanding of the complex, dynamic and interrelated social processes that inform social and emotional wellbeing for Indigenous people living in an urban setting. This study has contributed to understanding some of the pathways of social determinants of health that may lead to well-being and good health. The use of life course narratives with a capability approach distinguishes this paper from existing scholarship that has largely focused on quantifying these relationships. This has allowed for a more sustained and rich focus on the roles of resilience and wellbeing for the holistic health of Indigenous people in urban Australia. This highlights the need for more diversity in study objectives and its methods in Indigenous health research, in ways that can prioritise the resilience narratives of Indigenous people. Of interest to policy makers, the findings support the use of affirmative action initiatives to reduce socioeconomic disadvantage. Promoting family wellbeing and community capacity building approaches is important as they can positively influence health and wellbeing trajectories for Indigenous people in Australia. The findings suggest the use of strength-based, capability-focused narrative therapies as a culturally-appropriate approach for working with Indigenous people.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof David Trigger, Dr Chelsea Bond, Dr Yvette Roe, Dr Bec Jenkinson, Dr Baptiste Godrie and two anonymous reviewers for providing feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. This research was undertaken at the School of Social Science, The University of Queensland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sophie Hickey

Sophie Hickey is a postdoctoral mixed-methods researcher with a strong research interest in social inequalities in health and wellbeing.

Notes

1 Torres Strait Islander status was not collected, hence could not be included in this study unless the person identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

2 Three people who identified as Aboriginal chose not to participate in the qualitative interviews: one had just had a baby, one recently moved to an area with poor phone reception, and contact was lost during follow-up with another.

References

- ABS. 2010. The City and the Bush: Indigenous Wellbeing Across Remoteness Areas. Australian Social Trends. Cat. No. 4102.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- AIHW. 2015. The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: An Overview: 2015. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Andersson, N., and R. Ledogar. 2008. “The CIET Aboriginal Youth Resilience Studies: 14 Years of Capacity Building and Methods Development in Canada.” Pimatisiwin 6 (2): 65–88.

- Atkinson, R. 2004. “Life Story Interview.” In Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, edited by M. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, A. and T, and Futing Liao, 567–571. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Biddle, N. 2014. “Measuring and Analysing the Wellbeing of Australia’s Indigenous Population.” Social Indicators Research 116 (3): 713–729.

- Biddle, N., and H. Swee. 2012. “The Relationship Between Wellbeing and Indigenous Land, Language and Culture in Australia.” Australian Geographer 43 (3): 215–232.

- Bockstael, E., and K. Watene. 2016. “Indigenous Peoples and the Capability Approach: Taking Stock.” Oxford Development Studies 44: 265–270.

- Bond, C. 2005. “A Culture of Ill Health: Public Health or Aboriginality?” Medical Journal of Australia 183 (1): 39–41.

- Bond, C., and D. Singh. 2020. “More Than a Refresh Required for Closing the Gap of Indigenous Health Inequality.” Medical Journal of Australia 212 (5): 198–199.

- Brough, M. 2001. “Healthy Imaginations: A Social History of the Epidemiology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health.” Medical Anthropology 20 (1): 65–90.

- Crotty, M. 1998. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. London: SAGE Publications.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2020. Closing the Gap Report 2020. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Dockery, A. M. 2010. “Culture and Wellbeing: The Case of Indigenous Australians.” Social Indicators Research 99 (2): 315–332.

- Durie, M. 1994. Whaiora: Māori Health Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Durie, M. 1998. Te Mana, Te Kawanatanga: The Politics of Māori Self-Determination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eades, S., J. Taylor, S. Bailey, A. Williamson, J. Craig, and S. Redman. 2010. “The Health of Urban Aboriginal People: Insufficient Data to Close the Gap.” Medical Journal of Australia 193 (9): 521–524.

- Fredericks, B. 2010. “What’em with the Apology? The National Apology to the Stolen Generations Two Years On.” Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 13 (1): 19–30.

- Hausler, S., E. Golden, and J. Allen. 2006. “Narrative in the Study of Resilience.” The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 61 (1): 205–227.

- Hickey, S. 2015. “It All Comes Down to Ticking a Box: Collecting Aboriginal Identification in a 30-Year Longitudinal Health Study.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2015 (2): 33–45.

- Hickey, S. 2016. “They Say I’m Not a Typical Blackfella: Experiences of Racism and Ontological Security in Urban Australia.” Journal of Sociology 52 (4): 725–740.

- Holland, C., P. Dudgeon, and H. Milroy. 2013. The Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Families and Communities. Canberra: National Mental Health Commission.

- HREOC. 1997. Bringing Them Home: Report of the National Inquiry Into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Ivanitz, M. 2000. “Achieving Improved Health Outcomes for Urban Aboriginal People: Biomedical and Ethnomedical Models of Health.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 59 (3): 49–57.

- Jones, R., K. Thurber, and J. Chapman. 2018. “Study Protocol: Our Cultures Count, the Mayi Kuwayu Study, a National Longitudinal Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing.” BMJ Open 8: e023861.

- Jordan, K., H. Bulloch, and G. Buchanan. 2010. “Statistical Equality and Cultural Difference in Indigenous Wellbeing Frameworks: A New Expression of an Enduring Debate.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 45 (3): 333–362.

- Kirmayer, L., S. Dandeneau, E. Marshall, M. Phillips, and K. Jenssen Williamson. 2011. “Rethinking Resilience from Indigenous Perspectives.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 56 (2): 84–91.

- Lahn, J. 2013. Aboriginal Professionals: Work, Class and Culture. CAEPR no. 89/2013. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University.

- Lincoln, Y., and E. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Maaka, R., and C. Andersen, eds. 2006. The Indigenous Experience: Global Perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Martin, R., C. Fernandes, C. Taylor, A. Crow, D. Headland, N. Shaw, and S. Zammit. 2019. “We Don’t Want to Live Like This: The Lived Experience of Dislocation, Poor Health, and Homelessness for Western Australian Aboriginal People.” Qualitative Health Research 29 (2): 159–172.

- Mason, J. 1996. Qualitative Researching. London: SAGE Publications.

- McAdams, D., J. Reynolds, M. Lewis, A. Patten, and P. Bowman. 2001. “Redemption and Contamination, When Bad Things Turn Good and Good Things Turn Bad: Sequences of Redemption and Contamination in Life Narrative and Their Relation to Psychosocial Adaptation in Midlife Adults and in Students.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27 (4): 474–485.

- Moreton-Robinson, A. 2009. “Imagining the Good Indigenous Citizen.” Cultural Studies Review 15 (2): 61–79.

- Nadin, S., and C. Cassell. 2006. “The Use of a Research Diary as a Tool for Reflexive Practice.” Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 3 (3): 208–217.

- NAHSWP. 1989. A National Aboriginal Health Strategy. Canberra: National Aboriginal Health Strategic Working Party (NAHSWP).

- Najman, J., W. Bor, M. O’Callaghan, G. Williams, R. Aird, and G. Shuttlewood. 2005. “Cohort Profile: The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP).” International Journal of Epidemiology 34 (5): 992–997.

- Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pals, J., and D. McAdams. 2004. “The Transformed Self: A Narrative Understanding of Posttraumatic Growth.” Psychological Inquiry 15 (1): 65–69.

- Pezalla, A., J. Pettigrew, and M. Miller-Day. 2012. “Researching the Researcher-as-Instrument: An Exercise in Interviewer Self-Reflexivity.” Qualitative Research 12 (2): 165–185.

- Priest, N., T. Mackean, E. Waters, E. Davis, and E. Riggs. 2009. “Indigenous Child Health Research: A Critical Analysis of Australian Studies.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33 (1): 55–63.

- RCIADIC. 1991. National Report. Vol. 4. Canberra: Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

- Reith, G., and F. Dobbie. 2011. “Beginning Gambling: The Role of Social Networks and Environment.” Addiction Research & Theory 19 (6): 483–493.

- Robeyns, I. 2011. The Capability Approach. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/capability-approach.

- Sangha, K., A. Le Brocque, R. Costanza, and Y. Cadet-James. 2015. “Ecosystems and Indigenous Well-Being: An Integrated Framework.” Global Ecology and Conservation 4: 197–206.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sherwood, J. 2013. “Colonisation – It’s Bad for Your Health: The Context of Aboriginal Health.” Contemporary Nurse 46 (1): 28–40.

- Smith, L. T. 1999. Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

- Stoneham, M., J. Goodman, and M. Daube. 2014. “The Portrayal of Indigenous Health in Selected Australian Media.” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 5 (1): 5–13.

- Swan, P., and B. Raphael. 2006. Ways Forward: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health Policy. Canberra: Australian Commonwealth Government.

- Ten Fingers, K. 2005. “Rejecting, Revitalizing, and Reclaiming: First Nations Work to Set the Direction of Research and Policy Development.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 96: 60–63.

- Tomkins, S. 1987. “Script Theory.” In The Emergence of Personality, edited by J. Aronoff, A. I. Rabin, and R. A. Zucker, 147–216. New York: Springer.

- Ungar, M. 2008. “Resilience Across Cultures.” British Journal of Social Work 38 (2): 218–235.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. A/RES/61/295. Accessed January 31, 2019. https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html.

- Vaughan, D. 2011. “The Importance of Capabilities in the Sustainability of Information and Communications Technology Programs: The Case of Remote Indigenous Australian Communities.” Ethics and Information Technology 13: 131–150.

- Vicary, D., and B. Bishop. 2005. “Western Psychotherapeutic Practice: Engaging Aboriginal People in Culturally Appropriate and Respectful Ways.” Australian Psychologist 40: 8–19.

- Walter, M. 2010. “The Politics of the Data: How the Australian Statistical Indigene is Constructed.” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3 (2): 45–56.

- Waugh, E., and L. Mackenzie. 2011. “Ageing Well from an Urban Indigenous Australian Perspective.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 58 (2011): 25–33.

- Yap, M., and E. Yu. 2016. “Operationalising the Capability Approach: Developing Culturally Relevant Indicators of Indigenous Wellbeing – An Australian Example.” Oxford Development Studies 44 (3): 315–331.

- Ypinazar, V., S. Margolis, M. Haswell-Elkins, and K. Tsey. 2007. “Indigenous Australians’ Understandings Regarding Mental Health and Disorders.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 41 (6): 467–478.