ABSTRACT

Recurrent acute pancreatitis is beginning to be recognized as an intermediary stage in the continuous spectrum between acute and chronic pancreatitis. It is crucial to identify this disease stage and intervene with diagnostic and therapeutic modalities to prevent the painful and irreversible condition of chronic pancreatitis. We review the recent advances in diagnosing and managing this important ‘call for action’ condition.

Introduction

Pancreatitis is a common inflammatory condition often requiring hospitalization. In its acute form, its incidence is approximately 13–45/100,000 persons in the US with about 275,000 hospitalizations per year costing $2.6 billion annually [Citation1]. Recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) is defined as the presence of at least 2 separate documented episodes of pancreatitis with a period of resolution in between, and the absence of definitive changes of CP. CP is characterized clinically by chronic abdominal pain and functional pancreatic insufficiency with imaging findings such as pancreatic atrophy, ductal dilation and pancreatic calcifications [Citation2,Citation3]. We review the current understanding of this important intermediary stage between acute (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP).

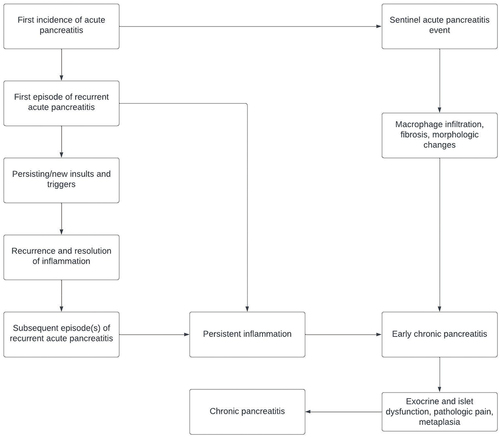

The term ‘recurrent acute pancreatitis’ (RAP) first appeared in the literature in 1948 [Citation4]. Alternative terms such as relapsing acute pancreatitis have been used in the literature and textbooks in the past. Previous authors have proposed that RAP is the second stage of CP pathogenesis; it follows from a sentinel acute pancreatitis event and is a precursor to early chronic pancreatitis (ECP) [Citation5]. ECP is characterized by persistent inflammation; in contrast, inflammation in RAP resolves between episodes (but has residual structural changes). Recurrent inflammatory episodes eventually lead to the pathophysiological processes characteristic of CP, including immune dysregulation, acinar and islet dysfunction and metaplasia [Citation5].

About 20–25% of cases of RAP will develop CP [Citation6,Citation7], and this has been observed to most frequently occur in young men [Citation7,Citation8]. Identifying and treating the cause of RAP is of utmost importance, as CP is an irreversible painful condition with high morbidity and mortality [Citation9]. RAP represents a disease state where the underlying pancreatic inflammation is still potentially reversible, and therefore increased awareness of identifying and treating this condition can potentially avoid progression to CP.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is characterized by the destruction of the acinar cell – the functional unit of the exocrine pancreas. Inappropriate activation of pancreatic enzymes, kinins, and the complement cascade leads to subsequent autodigestion of pancreatic acini [Citation10]. This pathologic process may be triggered by a number of events; commonly injury or obstruction of the pancreatic ductal system, or inappropriately elevated intracellular calcium within the pancreatic acini. Subsequent downstream conversion of trypsinogen to trypsin within the pancreatic acini enables resultant damage [Citation10]. AP is subclassified into either interstitial edematous pancreatitis or necrotizing pancreatitis types. Both types can lead to local and systemic complications including fluid collections, pseudocyst, localized necroses, acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and others [Citation10]. While some cases of AP can resolve uneventfully, up to 20–25% may recur [Citation6,Citation7].

Whitcomb proposed that a sentinel acute pancreatitis event (SAPE) was needed to jump-start the chronic pancreatitis disease process of macrophage infiltration and fibrosis, which is then exacerbated by further acute pancreatitis events [Citation11]. This theory has also been supported by imaging studies that have found RAP patients develop some imaging changes consistent with CP [Citation12]. A meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies which included about 8,500 patients found that 36% of all RAP patients developed CP [Citation13], while a separate study found that among patients who had a fourth episode of RAP, 50% went on to develop CP [Citation7]. The process by which AP can progress to CP via RAP and ECP is summarized in .

The etiologies or ‘triggers’ of RAP can be classified according to the TIGAR-O system [Citation14]. A summary of these causes and their clinicopathological context, categorized according to this system, can be seen in . These triggers have been primarily identified in studies of AP patients [Citation15].

Table 1. Causes of RAP, categorized by the TIGAR-O system. CFTR = Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator, SPINK-1 = serine protease inhibitor kazal-type 1, PRSS1 = protease serine 1, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Demographics

A study of 1,829 AP and 683 RAP patients in China found that RAP patients were significantly more likely to be younger than AP patients and male, with similar findings reported by Hegyi et al. [Citation7,Citation8]. Another, retrospective review of 250 AP and RAP patients also found RAP patients to be younger (53 vs 55, RAP vs AP) and more likely to be male (70% vs 63%, RAP vs AP), although these results were not significant [Citation16]. The often-described demographic of the older female patient who suffers from gallstones does not seem to apply to RAP patients.

Clinical presentation and disease course

Recent studies suggest that RAP follows a different clinical course compared to AP. Ironically, the clinical severity in patients presenting with RAP appears to be lower, especially in early phases of their presentation, but has more structural complications. Lee et al. reported decreased likelihood of multisystem organ failure and ICU admission in RAP patients, with respective ORs of 0.14 (95% CI 0.01–0.76) and 0.24 (95% CI 0.06–0.91) when compared to AP patients [Citation17]. Among 1567 patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital, Song et al. found that disease severity scores such as Ranson’s, BISAP, SOFA and APACHE II scores were all significantly lower in RAP patients (p < 0.001 for all) when compared to patients with AP [Citation18]. Lipase levels were significantly lower in RAP compared to AP (p = 0.0002), and leukocytosis and fever were less common but not significantly so [Citation16]. While the clinical manifestations of RAP were of lower severity, the structural complications as classified by modified CT severity index (MCTSI) paradoxically reveal more severe disease processes in RAP than AP [Citation16].

Zhang et al. have proposed unifying these seemingly contradictory findings by considering the clinical course in terms of early phase and late phase RAP, as per the revised Atlanta classification [Citation8,Citation19]. The early phase is the first week from symptom onset, with the late phase comprising the second week onwards. In their retrospective cross-sectional study of 896 RAP patients and 2,421 AP patients, they found that the RAP patient group had a significantly higher proportion of acute necrotizing collections (ANCs) in the early stage (p = 0.03) and late stage (p = 0.004) and a higher proportion of walled-off necrosis in the early stage (p = <0.001). RAP patients had a higher median CT severity index (CTSI) in the late stage [Citation19]. These findings support the belief that acute inflammation contributes to the structural changes associated with the early stage of RAP and post-acute inflammatory changes like scarring and mechanical complications contribute to the structural changes in later stage RAP.

Management

In the early phase of acute presentation, the current practice is to manage RAP patients similarly to AP patients with clinical assessment and evidence of organ dysfunction guiding management. Pain control, fluid resuscitation, and early enteral nutrition are the mainstays of therapy [Citation10,Citation20]. The explicit goals of RAP management are to identify and, if possible, eliminate the trigger or source of ongoing insults to the pancreas, followed by reversal of the inflammatory process. Identifying the etiology and the risk factors (smoking, alcohol etc.) are equally important and a multi-modal approach of using therapeutics, genetic testing and counseling with serial follow-up in the outpatient setting is crucial. It could be argued that the work up of any index AP patient should include investigations which prevent RAP in the first place but this may be hard to implement in real world practice due to high cost of advanced imaging and genetic studies. This is also complicated by the fact that up to 29% of patients with AP will have recurrent episodes even after an etiology was found during index AP episode [Citation21].

The recognition of RAP and its diverse etiologies can help drive more effective management to avoid the complications of CP. Therapeutics will vary significantly according to the identified etiologies, with each etiology having a specific intervention. In the cases involving toxic causes, removal of the offending agent is critical. In a significant percentage of these cases, alcohol consumption is the culprit. Obstructive causes will require relief of the obstruction; autoimmune causes may require anti-inflammatory treatment, and so on. A multidisciplinary approach can help avoid the fibrotic complications/mechanical issues which predispose to progression to CP. Due to the varying clinical nature of this disease state, many of these patients require carefully tailored management plans that can address specific needs and help to engage in appropriate longitudinal care [Citation22]. Education of the patient is a critical step, because the lack of severity of clinical findings belies the structural changes that are occurring. This may give patients a false sense of security and diminish their motivation to make the necessary behavior changes and potentially reduce the alacrity with which patients will seek additional care. While the initial care may occur in inpatient and tertiary or quaternary centers, much of the workup may need to take place in the outpatient setting, which requires the patient to be highly engaged with longitudinal care [Citation22].

In his chapter in Clinical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Stevens writes that the management plan may be separated into three phases [Citation15]. The initial management, usually during the acute hospitalization phase, consists of a detailed history and laboratory evaluation, followed by imaging studies (trans-abdominal ultrasound and CT scans), and should aim to identify common causes of RAP (e.g. high alcohol intake or biliary causes). The second step in management aims to identify rarer causes and consists of specialist studies such as genetic or autoimmune testing, and more detailed testing such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or MRCP, which can also occur in an appropriate outpatient setting. A review of potential offending drugs taken by the patient using the recently published classification system is recommended [Citation23]. The tertiary phase, which often occurs at a tertiary or quaternary care center, or any Pancreatic Center of Excellence, may involve endoscopic or surgical techniques to provide targeted diagnostic procedures and treatment. These techniques include minimally invasive strategies such as ERCP, as well as major and minor sphincteroplasties and partial pancreatectomies in patients with masses or IPMNs. These advanced interventions help to demonstrate to the patient that structural changes are occurring despite minimal symptoms and require active patient engagement to minimize the likelihood of disease progression.

As noted previously, RAP may present with milder clinical findings but more severe radiological findings when compared to AP. Advanced radiological intervention is an effective diagnostic modality. As per American College of Radiology guidelines for AP, to characterize the potentially higher burden of necrosis and pseudocysts in RAP, MRI imaging may be superior for assessing fluid collections with T2-weighted imaging, particularly differentiating between pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis [Citation24]. Additionally, MRI with MRCP can assess for ductal disruption, which is a common complication of necrotizing pancreatitis and can lead to fistula formation, infection and added morbidity. MRCP has been shown to achieve 95% accuracy in detecting pancreatic duct disruption [Citation25]. However, CT with contrast is useful for detecting infection and fistulas and the ACR guidelines conclude that these two modalities should be used complementarily. MRI avoids radiation exposure, and when serial examinations are likely to be useful it may be preferable to CT. Per a recent practice update from the AGA, endoscopic ultrasound is the preferred diagnostic test for unexplained acute and recurrent pancreatitis [Citation26].

Based on our literature review, we propose the following clinical pathway to pursue the diagnostic and related therapeutic strategies in patients presenting with RAP (see ).

Figure 2. Proposed pathway to evaluate RAP. Genetic testing is particularly indicated if there is a family history of acute pancreatitis and young age of presentation; other indicators for IgG4 testing (other than HISORt criteria) include diffuse enhancement, capsular enhancement or multiple duct strictures. It is also worth noting that endoscopic ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice in patients with single or recurrent idiopathic acute pancreatitis [Citation27].

![Figure 2. Proposed pathway to evaluate RAP. Genetic testing is particularly indicated if there is a family history of acute pancreatitis and young age of presentation; other indicators for IgG4 testing (other than HISORt criteria) include diffuse enhancement, capsular enhancement or multiple duct strictures. It is also worth noting that endoscopic ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice in patients with single or recurrent idiopathic acute pancreatitis [Citation27].](/cms/asset/85552b65-b9a6-4888-96dc-37d19c1125e0/ihop_a_2348990_f0002_oc.jpg)

Indications for genetic testing include a family history of pancreatitis or a young age of presentation [Citation15]. Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) may be suspected if characteristic radiological findings are seen, such as diffuse pancreatic enlargement, capsular enhancement or multiple duct strictures. AIP is diagnosed using a scoring system such as HISORt, which considers histology, imaging, serology (IgG4 and total IgG), other organ involvement and response to therapy [Citation28,Citation29].

Prognosis

AP, RAP and CP are now believed to lie on a continuous spectrum of disease. A diagnosis of RAP confers a markedly increased risk of progression to CP, with one study finding that of all patients who had a fourth episode of RAP, 50% went on to develop CP, and another finding that 36% of all RAP patients develop CP [Citation7,Citation13]. There is evidence that the etiology of RAP plays a role in likelihood of progression to CP; Hegyi et al. reported the rate of alcoholic etiology increased from AP to RAP to CP (19.4%, 39.1% and 51.6% respectively) [Citation7], and a previous study found that very heavy drinking (>5 drinks/day) was significantly associated with development of CP (OR 3.10 when compared to abstainers and light drinkers, 95% CI 1.87–5.14, p < 0.001) [Citation30]. However, Nøjgaard et al. found that tobacco smoking was the strongest risk factor associated with progression to CP [Citation31]. Yadav et al. found both RAP and tobacco abuse to be significant risk factors for CP [Citation21].

Studies have looked at both inflammatory and pancreatic enzymes biomarkers to analyze any prognostic value for disease progression [Citation7]. One notable finding is that lipase and amylase levels tend to be significantly lower with subsequent episodes of RAP when compared to AP. This is thought to be consistent with progressive damage to acinar cells from recurrent episodes and loss of exocrine function. Additionally, the study found a drop in red blood cell count among study participants with increasing episodes of RAP and progression to CP, and increased incidence of pseudocysts.

Some imaging findings may validate disease progression in RAP patients. An MRI study which grouped patients by the number of attacks of AP found that there was a significant reduction in the total pancreatic volume (TPV) and tail diameter by their third attack, with an average TPV reduction of 22% - this is consistent with the findings identified in CP patients [Citation32].

Discussion

The incidence of AP in the US is estimated to be around 100–140 per 100,000 with at least 300,000 Emergency Department visits annually and rising [Citation10]. The incidence of CP in the US adult population is estimated to be around 4–5 new cases per 100,000 per year [Citation33]. Each hospitalization has a median cost of about $7,000. Once CP develops, patients experience chronic pain and have higher mortality [Citation9]. RAP represents a disease state which reflects ongoing pancreatic acinar insult and implies a level of reversibility.

As noted earlier, RAP patients are younger and more likely to be male than their AP counterparts [Citation7,Citation8]. Alcohol has been linked as a risk factor for RAP, with one group reporting that 39.1% of cases had an alcoholic etiology compared to just 19.4% with AP [Citation7]. Cigarette smoking is another important risk factor; it has been identified as a risk factor for both development of RAP and progression to CP [Citation21,Citation31]. Equally, the authors found that biliary causes were less associated with RAP compared to AP (20.7% of RAP cases had biliary etiology, compared. To 50.2% of AP cases). In the Chinese population analyzed by Zhang et al., they found hypertriglyceridemia to be a significant risk factor for RAP, as well as the most common etiology of RAP patients (38%) [Citation8]. This relatively high proportion of patients with hypertriglyceridemia in this study may be attributable to the study population in China and study design.

The progression of RAP to CP may also involve an intermediary – early chronic pancreatitis (ECP). The first diagnostic criteria for ECP were formulated by the Japan Pancreas Society in 2009 and revised in 2019 [Citation34,Citation35]. Requirements for a diagnosis of ECP included cases that did not qualify as ‘definite’ or ‘probable’ CP, but still satisfied two of the four clinical criteria and corresponding imaging findings on EUS or ERCP. However, the criteria have not been adopted internationally due to some key limitations – the imaging findings are not specific for ECP, and there is a requirement of continued heavy drinking [Citation36]. In a clinical scenario, it may be difficult to delineate between RAP and ECP. This further solidifies the concept that pancreatitis should be viewed as a continuum of disease from AP to CP via RAP and ECP, with a degree of reversibility associated with the initial stages.

There are very limited clinical trials to guide the diagnostic work up and management strategies for patients presenting with RAP. Our proposed work up () summarizes the current consensus. While managing a patient presenting with RAP, an astute clinician should consider the following questions. What is driving the recurring episodes? Is the persisting source of injury in this patient genetic, autoimmune, or due to mechanical obstruction? A layered approach of diagnostics with primary and secondary workups as outlined earlier with judicious use of imaging and referral to pancreatic centers of excellence is suggested. It is, however, possible to complete much of the workup in the outpatient setting, especially when the patient has been informed of how the structural changes can progress if appropriate interventions are not made.

The main diagnostic imaging tools include contrast enhanced CT, MRI/MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound. The latter may be used as part of a therapeutic strategy with ERCP depending on findings. Endoscopic ultrasound has recently been recommended as the preferred diagnostic test for unexplained RAP and AP; this is in contrast to the American College of Radiology’s appropriateness criteria, where they did not recommend endoscopic ultrasound as a diagnostic modality [Citation24,Citation26]. This area is, however, rapidly evolving and endoscopic ultrasound guided drainage of necrotic collections is a valuable minimally invasive technique in selective patients.

As mentioned previously, RAP has a diverse set of etiologies and the subsequent treatment may vary widely depending on the identified cause of disease. Obstructive causes of RAP are commonly treated with ERCP and sphincterotomy, followed by placement of a biliary stent. Early cholecystectomy is recommended for RAP from biliary microlithiasis [Citation15], although there is evidence that cholecystectomy following the index episode of biliary pancreatitis reduces the risk of RAP and therefore should be considered at the initial presentation of acute pancreatitis [Citation37]. Autoimmune pancreatitis is treated with corticosteroid therapy but relapses are more likely with Type I AIP [Citation15]. Use of nonionic isosmotic contrast agents for ERCP to lower risk of procedure associated recurrent pancreatitis is already gaining wide acceptance. Additional therapies currently undergoing trials that may have profound implications in managing patients with RAP include newer treatments for hypertriglyceridemia, CFTR modulatory therapy. Use of methotrexate and infliximab in AP is also being studied in multicenter randomized trials [Citation38]. In the future, Orai1 calcium channel inhibitors may play a role in preventing the progression of RAP to CP [Citation39].

Conclusion

In conclusion, recurrent acute pancreatitis is a reversible disease state that lies on the spectrum between acute and chronic pancreatitis. It is a harbinger for the development of the painful and irreversible disease state of chronic pancreatitis, for which there are no curative treatments at this time. Earnest investigation and patient education, including a robust discussion of therapeutic strategies, need to be initiated upon identification to prevent development of end state disease. Careful history assessment, risk factor assessment, testing for markers for autoimmunity, genetic mutations and use of imaging techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound and MRI/MRCP may be needed to identify the etiology and initiate therapeutics. As we step into the era of precision medicine, we anticipate that power of big data and AI driven management modules will allow for individualized diagnostic and therapeutic measures driven by patient’s genetics and clinical picture. Current knowledge gaps include demographic data stratified by ethnicity, as well as how the underlying cause of RAP may vary by ethnicity. Further clinical trials are needed to advance understanding and improve management of this ‘call for action’ disease state.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the research and preparation of the manuscript. No generative AI was used at any stage. Thomas Edmiston – Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; Dr Kittane Vishnupriya – Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing; Dr Arjun Chanmugam – Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. The epidemiology of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol. 2013 [cited 2023 Sep 22];144(6):1252–1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.068

- Machicado JD, Yadav D. Epidemiology of recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis: similarities and differences. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 [cited 2023 Sep 12];62(7):1683–1691. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4510-5

- Issa Y, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment in chronic pancreatitis: an international survey and case vignette study. HPB (Oxford). 2017 [cited 2023 Sep 12];19(11):978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.07.006

- Doubilet H, Mulholland JH. Recurrent acute pancreatitis: observations on etiology and surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1948 [cited 2023 Sep 3];128(4):609. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194810000-00001

- Whitcomb DC, Frulloni L, Garg P, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: an international draft consensus proposal for a new mechanistic definition. Pancreatology. 2016 [cited 2023 Aug 29];16:218. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.02.001

- Ghiță AI, Pahomeanu MR, Negreanu L. Epidemiological trends in acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort in a tertiary center over a seven year period. World J Methodol. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 30];13:118. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i3.118

- Hegyi PJ, Soós A, Tóth E, et al. Evidence for diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis after three episodes of acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional multicentre international study with experimental animal model. Sci Rep 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 30];11:1367. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80532-6

- Zhang J, Du J-J, Tang W, et al. CT characteristics of recurrent acute pancreatitis and acute pancreatitis in different stages–a retrospective cross-sectional study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 29];13:4222. doi: 10.21037/qims-22-1172

- Yadav D, Timmons L, Benson JT, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 [cited 2023 Sep 12];106(12):2192–2199. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.328

- Mederos MA, Reber HA, Girgis MD. Acute pancreatitis: a review.JAMA. 2021 [cited 2023 Aug 6];325(4):382–390. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20317

- Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis: new insights into acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1999 [cited 2023 Aug 3];45(3):317–322. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.317

- Guda NM, Nøjgaard C. Recurrent acute pancreatitis and progression to chronic pancreatitis. Pancreapedia: The Exocrine Pancreas Knowledge Base. Milwaukee, WI and Copenhagen, Denmark: Aurora St.Luke’s Medical Center and Hvidovre University Hospital; 2015 Sep 23. doi: 10.3998/panc.2015.39

- Sankaran SJ, Xiao AY, Wu LM, et al. Frequency of progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis and risk factors: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1490–1500.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.066

- Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001 [cited 2023 Aug 2];120(3):682–707. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22586

- Stevens T, Freeman ML. 57 - Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis. In: Chandrasekhara V, Elmunzer BJ, Khashab MA, editors. Clin Gastrointest Endosc. 3rd ed. Elsevier. 2019;661–673.e3. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-41509-5.00057-8

- Boumezrag M, Harounzadeh S, Ijaz H, et al. Assessing the CT findings and clinical course of ED patients with first-time versus recurrent acute pancreatitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(2):304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.061

- Lee PJW, Bhatt A, Holmes J, et al. Decreased severity in recurrent versus initial episodes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015 [cited 2023 Jul 30];44(6):896–900. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000354

- Song K, Guo C, He L, et al. Different clinical characteristics between recurrent and non-recurrent acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study from a tertiary hospital. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 30];28(4):282–287. doi: 10.4103/sjg.sjg_324_21

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013 [cited 2023 Jul 30];62(1):102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779

- Vishnupriya K, Chanmugam A. Acute pancreatitis: the increasing role of medical management of a traditionally surgically managed disease.Am J Med. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 12];135(2):167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.08.021

- Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis.Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 [cited 2023 Aug 3];107(7):1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.126

- Whitcomb DC. What is personalized medicine and what should it replace? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 [cited 2023 Aug 3];9(7):418–424. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.100

- Saini J, Marino D, Badalov N, et al. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: an evidence-based classification (revised). Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 24];14(8):e00621. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000621

- Porter KK, Zaheer A, Kamel IR, et al. ACR appropriateness Criteria® acute pancreatitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019 [cited 2023 Jul 27];16(11):S316–S330. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.05.017

- Drake LM, Anis M, Lawrence C. Accuracy of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in identifying pancreatic duct disruption.J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012 [cited 2023 Jul 27];46(8):696–699. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825003b3

- Strand DS, Law RJ, Yang D, et al. AGA clinical practice update on the endoscopic approach to recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 12];163(4):1107–1114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.079

- Somani P, Sunkara T, Sharma M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in idiopathic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 [cited 2024 Apr 24];23(38):6952. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i38.6952

- Gallo C, Dispinzieri G, Zucchini N, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: cornerstones and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 [cited 2024 Apr 24];30(8):817–832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i8.817

- Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the mayo clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(8):1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017

- Yadav D, Hawes RH, Brand RE, et al. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and the risk of recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2009 [cited 2023 Jul 30];169(11):1035. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.125

- Nøjgaard C, Becker U, Matzen P, et al. Progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis: prognostic factors, mortality, and natural course. Pancreas. 2011 [cited 2023 Aug 3];40(8):1195–1200. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318221f569

- DeSouza SV, Priya S, Cho J, et al. Pancreas shrinkage following recurrent acute pancreatitis: an MRI study. Eur Radiol. 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 3];29:3746–3756. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06126-7

- Machicado JD, Dudekula A, Tang G, et al. Period prevalence of chronic pancreatitis diagnosis from 2001–2013 in the commercially insured population of the United States. Pancreatology. 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 12];19(6):813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.07.003

- Shimosegawa T, Kataoka K, Kamisawa T, et al. The revised Japanese clinical diagnostic criteria for chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2010 [cited 2023 Aug 29];45(6):584–591. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0242-4

- Masamune A, Kikuta K, Kume K, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of chronic pancreatitis in Japan: introduction and validation of the new Japanese diagnostic criteria 2019. J Gastroenterol. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 29];55(11):1062–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00535-020-01704-9

- Whitcomb DC, Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, et al. International consensus statements on early chronic pancreatitis: recommendations from the working group for the international consensus guidelines for chronic pancreatitis in collaboration with the international Association of pancreatology, American pancreatic association, Japan pancreas society, pancreasFest working group and European pancreatic club. Pancreatology. 2018 [cited 2023 Aug 29];18:516–527. Available from: https://www/pmc/articles/PMC6748871/

- Da Costa DW, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, et al. Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 [cited 2024 Apr 18];386(10000):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00274-3

- Szatmary P, Grammatikopoulos T, Cai W, et al. Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 22];82(12):1251–1276. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01766-4

- Szabó V, Csákány-Papp N, Görög M, et al. Orai1 calcium channel inhibition prevents progression of chronic pancreatitis. JCI Insight. 2023;8 [cited 2023 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www/pmc/articles/PMC10371343/