Abstract

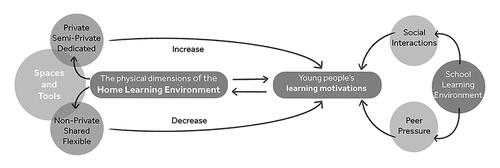

This article brings a novel perspective to the relationship between the physical dimensions of Home Learning Environments (HLE) and young people’s learning motivations during COVID-19 pandemic in UK. The architectural/physical focus of this investigation helps orient the reader to the literature/expertise I draw on. Based on 28 young people (16–18 years-old), the article evidences that comparing the HLE with the School Learning Environment (SLE), participants recognised the value of peer pressure and social learning environment to enhance learning motivations. Most participants found little use in home-schooling and wanted to return to in-person teaching. Students who adjusted the physical dimensions of the HLE were more motivated, especially if they had a private, semi-dedicated, or dedicated HLE. The article ends by exploring how the home-schooling experience during the COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to re-imagine HLE as a complementary learning environment to SLE, motivate young people to learn and support independent learning activities.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

Recent scholarship has focused on the Home Learning Environment (HLE), which is increasingly an important issue due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods (Aschenberger et al., Citation2022), where school closures kept 90% of all students globally out of school (United Nations, Citation2021). As a result, the HLE became crucial to support home schooling (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020; Cullinane & Montacute, Citation2020) with scholarship exploring issues such as the importance of parents/guardians (Bhamani, et al., Citation2020); inequalities of young people’s experiences (Andrew et al., Citation2020; Lamb et al., Citation2020; Holt & Murray, Citation2021) the impact on student performance and long-term development implications (Niklas, et al., Citation2021). There is a need to bring more research about the implications of COVID-19 pandemic on education (Feller & Stuart, Citation2021).

Balancing home and school life and loss of motivation where some of challenges reported by students during COVID-19 (Chiu & Lapeyrouse, Citation2021). It is clear that students’ learning environment, academic motivation, learning strategies and level of engagement influence the academic success (Cayubit, Citation2022). However, what is missing is any consideration between physical dimensions of the HLE and young people’s learning motivations. That relationship is important because it helps identify ways of improving the HLE and create physical learning environments that motivate young people to learn and be focused. Favourable HLE supports children’s literacy, numeracy and social development (Niklas et al., Citation2016). We know that in a primary school context, physical learning environments can impact the way we learn, behave or relate to each other and ultimately affect student’s outcomes (Barrett et al., Citation2015), but there is a lack of research that identifies ways of improving these physical learning environments, particularly in a secondary education context.

Responding to call, I focus on the relationship between the physical dimensions of the HLE and young people’s learning motivations and secondarily, explore the complementarity between the HLE and the School Learning Environment (SLE). I utilise visual methods, an innovative research approach in this field, in order to better characterise and understand the physical dimensions of the HLE. This paper analyses the two complementary dimensions of the physical HLE: learning spaces (solar orientation, adjacent spaces, context, architectural affordances, room layout, interior design and housing typology) and learning tools used at home (e.g. devices, books, whiteboards). These physical dimensions shape the HLE, provide different learning opportunities and psychological stimulation that may impact young people’s success later in life (Nampijja, et al., Citation2018).

The article is structured as follows:

First, I highlight the importance of the HLE in different research studies, map the references to the physical dimensions of the HLE and factors that affect young people’s learning motivations.

Second, I present the views of 28 young-people (16-18-year-olds) on their HLE and learning routines during the COVID-19 pandemic in two schools in Lancashire, UK. Through a qualitative research analysis and using visual methods, I mapped the physical dimensions of the HLE (spaces and tools) used by young people and its impact on their learning motivations.

Third, I characterise the physical dimensions of the HLE into two different categories: home learning spaces (bedroom, office, shared space, flexible space) and home learning tools (Digital tools, Analogue tools and Analogue learning aids) and map the positive and negative impact of these on young people’s learning motivations. From this analysis, emerges a comparison between HLE and SLE characteristics that highlights the complementarity of these.

Finally, I offer some possible directions for future research and policy recommendations related to our main findings. To improve young people’s learning motivation, we need to acknowledge the physical dimensions of HLE and adjust them accordingly. The appropriation of the physical HLE enhance young people learning’s motivations and helps them to be focused. Additionally, this research highlights the relevance of the HLE in providing a complementary space to the SLE and support independent learning activities.

This paper characterizes the physical dimensions (spaces and tools for learning) of the HLE during the COVID-19 pandemic and recognises their influence on young people’s learning motivations. The interest to carry this work is originated by acknowledge the lack references of physical dimensions in HLE studies and recognise the impact of physical learning spaces on learning motivations. Moreover, this paper brings a unique perspective that combines the architectural background with educational expertise of the author and shows how these two dimensions are intrinsically related and can inform each other.

Literature review

On the first section of our literature review, I analyse the importance of the HLE from an education perspective and highlight the lack of references to its physical dimensions, and on the second section I analyse the home physical environment, but not necessarily from an educational perspective. Through these references, I map what is known on this field and highlight the lacking of research that analysis the physical dimensions of the HLE and its impact on young people’s motivations.

The importance of the HLE for a child’s development is well recognized (HM Government, Citation2018; Nampijja et al., Citation2018). Research indicates that a positive HLE in the early years is one of the most influential factors in children’s development until the age of 18 (Melhuish et al., Citation2008; Sammons et al., Citation2015; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2019; Taggart et al., Citation2015). The HLE is one of the contexts within which children develop important competencies (Niklas et al., Citation2021) and cognitive development (Melhuish, et al., Citation2008). For instance, HLEs have been found to impact on child long-term development, cognitive development, vocabulary and literacy skills (Niklas et al., Citation2015; Lehrl et al., Citation2020), as well as student performance (Lehrl et al., Citation2020).

An example is the research developed by Lehrl et al. (Citation2020) that focuses on the relations between the early years learning environment and students’ academic outcomes in secondary school and shows the importance of caregivers to engage with their children in different learning activities.

Within this literature, despite the studies that link the socio-economic status with cognitive development (e.g., Feinstein, Citation2003; Melhuish et al., Citation2008) and the studies that relate HLE with physical activity (e.g., Tandon et al., Citation2014), there is no deep consideration of the physical settings of HLE and its impact on young people’s learning journey. Moreover, despite some longitudinal studies from childhood to adolescence (Toth et al., Citation2019; Lehrl et al., Citation2020), there is a limited research that considers the impact of the HLE on older pupils, especially 15–18 year olds. Furthermore, this paper responds to Lehrl et al.’s (Citation2020) call for future educational effectiveness studies should “address the role of the HLE in more detail and investigate how it may interact (possibly mediate or moderate) with institutional effects” (p. 4). There is a need to conduct further studies that explore how to support children and young people who experience low-quality HLE at different stages and promote collaboration between parents and educators.

Beyond education, the home environment has been assessed by different subjects and areas of knowledge (e.g., Medicine, Psychology, Behavioural Sciences, Human Nutrition) and highlighted different dimensions of the physical home environment. The home physical environment influences children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour (Tandon et al., Citation2014). However, most studies focus on the type of media equipment available (Maitland et al., Citation2013) and on the social home environment (Vaquera et al., Citation2018). There is a dearth of research that focuses on the impact of the architectural settings, affordances and physical characteristics of the home environment. This is important because the space available at home and the overall aesthetics affect the type and frequency of the activities performed by young people, i.e., playing in the garden, watching TV, going for a bike ride (Bradley et al., Citation2019; Evans, Citation2006; Sullu, Citation2023). Arguably, it is important to characterise the physical HLE, where young people spend significant amount of time, and analyse its powerful physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual implications (Rawat & Gulati, Citation2019).

According to Maitland et al. (Citation2013), “‘Future studies should prioritise investigating the influence of the home physical environment, and its interaction with the social environment, on objectively measured sedentary time and home context specific behaviours, ideally including technologies that allow objective measures of the home space.” For example, research on autism-friendly home environment (Nagib & Williams, Citation2017) provided insight into the physical, social, and psychological challenges affecting the quality of life of children and their families (e.g., adding extra space to the existing home, adjust the existing spaces to allow individual privacy). Through retrofit interventions, the adjustments on the physical home environment had an impact on the families “quality of life,” e.g., more safety, more time-out, less stress, freedom of movement, better personal space and privacy for all family members. This is relevant because these were some of the aspirations claimed by people during the lockdown caused by Covid-19 pandemic (Fukumura et al., Citation2021).

Aschenberger et al. (Citation2022) illustrate the importance of physical HLE for digitally supported learning in academic continuing education during COVID-19 pandemic and highlight the importance of perceiving the physical learning environment to meet individual needs. This article brings complementary insights and analysis in detail the physical learning environments characteristics by using visual methodologies.

Material and methods

Research context and research participants

This article presents the findings of a research project developed with 28 young people (16–18 year olds) in two schools in Lancashire, UK, and applied visual methodologies to elicit young learners’ schooling experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The project focused on the HLE, the research objectives were to characterise physical dimensions of the HLE (spaces and tools) and their relationship with young people’s learning motivations during COVID-19 pandemic.

The two schools are located in two different cities of Lancashire County in the North West of England. School A is located in Preston (the administrative centre of Lancashire) and School B in Lancaster (the county town of Lancashire). The two schools selected moved their teaching online during the first lockdown period of 2021 (from 6 January to 8 March 2021Footnote1), and their students were home schooling. Participants recruited were all attending their A-levels in a range of subjects and could reflect on their learning experience at home before and during COVID-19 pandemic with maturity and express their own learning motivations. In order to select the participants, the school’s partners sent an open invitation to all their 16–18 year old pupils. Participation was voluntary and to protect anonymity and confidentiality the participants are identified by pseudonymous (APA, Citation2020). The initial study was designed to collect data online; however, the participant’s recruitment process took longer in school B than in school A. This time-lag had an impact on the methods used. In school A, I collected the research data online during the lockdown in February/March 2021. In school B, I conducted research in-person when the lockdown restrictions were lifted in April/May 2021. Collecting data online or in-person was not a methodological option but a consequence of the recruitment process. I had 21 participants from school A (17 female, 3 male and 1 non-binary) and 7 participants from school B (3 female and 4 male). Most participants from school A are female; therefore, this research sample is not proportional to the school’s population and may constrain the generalisation of results.

Visual methods to gather young people’s perspectives

The project employed qualitative research methodology, combining focus group discussions (FGD) and collection of visual research techniques designed to address each research objective. In order to privilege participants’ understandings and perspectives (Hicks & Lloyd, Citation2018), visual methods were used to capture meanings of the research phenomena that cannot be reduced to text (Spawforth-Jones, Citation2021) and to enable the expression of emotions and tacit knowledge, and to encourage reflection (Pain, Citation2012). I conducted two different sessions, with groups up to 10 young people, 4 sessions with school A (2 × session 1 + 2 × session 2) and 2 sessions with school B (session 1 + session 2). I started each session by presenting the visual research task (step 1, ). To facilitate participant’s contributions, I created my own visuals from the HLE and presented them as an example (step 2, ). This strategy helped us to create a “bridge” between researcher and different participant’s experiences of reality (Pink, Citation2013). By the end of each session, I performed a FGD and discussed the visual elements produced (step 3, ). Asking participants to draw/illustrate their home learning environments and learning routines allowed them to highlight the key elements of their experiences (Kearney & Hyle, Citation2004). For participants uncomfortable in producing annotated drawings of their HLE, there was an option to use annotated photographs and/or text.

On the first session (), I asked each participant to produce an illustration/annotated photograph of their home learning space and assign emotional tags to objects (e.g., important/annoying/helpful/interesting). This exercise enabled us to characterise the physical dimensions of the HLE and learning activities. About 52% participants produced annotated drawings, 44% annotated photographs and 4% text only.

On the second session (), I asked each participant produce a storyboard to identify weekly routines and learning activities throughout one typical school’s week. This exercise enabled us to associate the physical dimensions of the HLE with the learning activities and learning motivation. This second session gave participants the opportunity to share their learning experiences from their own perspective (Chen, Citation2018) and most of them (74%) produced annotated drawings, with 7% annotated photographs and 19% represented their learning routine only through text.

Visual methods data analysis

Visual data (Banks, Citation2018) were analysed together with the focus group transcripts to safeguard the credibility and trustworthiness of the analysis (Hicks & Lloyd, Citation2018); creating a perceptive analysis that remains grounded in the data (Gibbs, Citation2007). The content analysis started with precise hypothesis (expectations) about well-defined variables (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Bell, Citation2004):

Hypothesis 1 – Young people acknowledge the impact of HLE on their learning motivations during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Hypothesis 2 – Young people consider the architectural affordances to improve their learning spaces and support learning motivation during COVID-19 Pandemic.

Hypothesis 3 - Young people actively engage with the physical dimensions of the HLE (spaces and tools for learning) and change them to increase their learning motivation.

In , I present the variables and values (also called “coders”) identified during the data analysis.

Table 1. Variables and values (also called “coders”) identified during the data analysis.

Results

The presents a graphical summary of the results obtained. Most participants (74%) identified their bedroom as their physical HLE. This private space with a semi-dedicated HLE would provide better spatial control and appropriation. However, since most of the bedrooms where used as multi-functional spaces (e.g., sleep, study, exercise, unwind), in some cases, there was not too much choice on where to place the desk: “My desk is quite small so if I have to write on paper, I usually do this leaning on a book as there is no space for my laptop and a worksheet on my desk at the same time” (Vanessa). Two of participants did not have a proper desk to study, so they were either using the floor or their own bed. The lack of dedicated HLE would affect learning motivation, as Taibah mentioned, “(…) At the moment I have half a desk but before I have had to work on my bed, boxes, the floor and stairs, all of which makes note-taking harder and reduces my energy and motivation significantly.” Two participants had two alternative physical home learning spaces. Claire had a private and dedicated learning space (office) in the attic and sometimes she would use the tiny desk in her bedroom as an occasional learning workspace. The diversity of learning spaces available at home allowed her to move according to her learning motivations and select the space according to the learning activity. Jonas is a boarding student and during lockdown, besides his bedroom he could also use the common room: “I was fortunate to have studied collaboratively with other people in the boarding house. This is a more effective learning space for me compared to my room.” This student valued the opportunity of having in-person social interaction. Like Jonas, this was a sentiment shared by many students in the sample that opted to use shared spaces at home instead of using their private bedrooms.

Figure 2. Graphical summary of the results obtained.

Molly did not associate any physical space to her HLE and identified her laptop as the main “space” where everything took place. This solution would allow her to flexibly move through the house and work from different spaces (e.g., sofa, bed, dining table). However, there was a lack of HLE reference and no signs of permanent spatial appropriation. For Anna, the laptop was also her “(…) most vital tool.” She would use it to attend her lessons, study, unwind and watch films or videos. However, according to her, “working on a laptop for long periods of time can cause eyestrain and headaches and I struggle to concentrate.” Like Molly, most of participants recognised the importance of having a high spec device (laptop/PC) to attend lessons and be connected to the world beyond home. Equally, most of them complaint about screen time during a day and the side-effects of this.

The participants who have a bedroom as their HLE were able to identify the advantages of having a more private and quiet area to learn. However, if it was not balanced with social interaction with peers/family members it could increase the sense of loneliness and lack of motivation to learn.

For participants using a common area of the house, e.g., the dining table, the physical HLE would include the tools that students normally take to school (e.g., booklets and textbooks, notebook, pencil case and laptop) and those spaces were temporarily occupied: “I do all lessons and most homework and revision here, occasionally I will go to my room if it is too noisy” (Jenny). In some cases, this was a deliberate option: ‘I prefer using my laptop rather than a Personal Computer (PC) because I can change where I want to study and do my work each day’ (Lara). On the one hand, the laptop would give students more flexibility when compared to a PC. On the other hand, in a flexible HLE, the ergonomic settings would be disregarded and students would work in less comfortable and healthy postural position.

Home learning tools

The HLE, the characteristics and position of different learning tools (e.g. table, chair, screen) may impact on the comfort and postural position. This problem was raised by several participants, e.g., back pain, uncomfortable chair and headache. However, only Moses () seemed to have carefully considered the configuration of his desk and the choice of his learning devices:

Figure 3. Moses’s home learning environment.

Dual monitor setup for more efficient multitasking, (…) raised to eye level and installed at an optimal distance. Monitor settings also allow me to lower the brightness or enable a blue light filter. Eyestrain is rarely an issue. (…) The wireless headphones with sound cancelation, the keyboard and mouse were selected to improve ergonomics. (…) The mousepad covers most of the desk space so the mouse has plenty of space. (…) The PC has ‘‘LEDs installed to provide a smooth environment under a heavy work load. (Moses)

Moses also included a drawing tablet which he would use to draw digital art/illustrations or ‘to write onto scanned in worksheets/texts where other students would use text boxes to write on a separate document’ (Moses).

The learning tools that students used were not only a question of choice, but also of affordability. Students tried to be creative and make the most of the learning tools available to then compensate the fact of not being able to work on their usual SLE. Sporadically, some students used the phone as their major learning tool due to problems with other devices: ‘Cameras aren’t usually required, but when they are, I use my phone because the one of my Chromebook doesn’t work. This can be quite inconvenient because the screen is very small and it can be a hassle to type in the chat/unmute myself’ (Claire). The frustration with different learning devices: ‘so many tabs needed, laptop is slowing down’ (Molly), and the inability to set up the right home learning environment was highlighted at different stages: ‘I use my tablet and Bluetooth keyboard for my online lessons. This can be difficult as it freezes sometimes and is not big enough, I have to prop it up with a book too.’(Katie).

The features of the devices and learning tools available would dictate the way students worked from home and either facilitate or challenge student’s learning activities and routines. Some students had a dedicated printer and they would use it very often:

In usual circumstances, the college would provide printed handouts for us to work with, but this isn’t currently possible. I could use a digital copy, but I have found I work better with a physical copy – I don’t really want to spend extra time staring at screen. (Claire).

Figure 4. Bedroom’s home learning environment.

For other students, the desk in their bedroom would have the laptop, a couple of folders and writing material as a sign of being used for learning activities. However, there were no other signs of appropriation and permanent use of the room as a learning space. In these cases, the learning tools could be easily packed away and omit the signs of the space being used as an HLE.

Aspects causing disruption to home learning

For most of participants, the bedroom was the place where most of the activities took place during lockdown. The bedroom was a space to sleep, to rest, to study, to exercise, to relax. There were several objects around the HLE that would support or disrupt these activities. In some cases, the space was surrounded by other objects to allow other uses, e.g. makeup:

Here is a pile of makeup and skincare things as I also use this desk space in the morning to get ready for the day. (Anna)

The mirror and makeup storage on my desk can be quite distracting as I’ll find myself messing around with them and not focusing on my lessons. (Katie)

Having the learning space in the bedroom was also mentioned as an issue. For Shanice, the ‘bed nearby is a distraction as well a temptation’. Most students were grateful from their HLE and for having ‘access to technology to be able to complete my online lessons fully’ (John). However, some of them would complain about using the same room all day, every day for different purposes:

It does get a bit repetitive having the same routine day in and day out, and using the same to do yoga, a little workout, to complete lessons, to complete homework, read books, and then sleep. You end up feeling fed up of the same four walls. (John)

From the speech bubbles added on his HLE illustration (), I understand that he was more motivated to play guitar, watch TV, play video games, and he would find studying and reading boring. Since he was struggling to be awake, he preferred to sleep or have a coffee. According to him, his daily learning routine could be illustrated in three steps: sleep in the morning, sleep during the day (and have someone trying to wake up him) and sleep during the night ().

Figure 5. Giles’s home learning environment.

When he sent the illustration via email, he also added a small description to the attachment: ‘Sorry it’s so simple, but I tend to sleep through even my classes … Pretty low at the moment so, it’s mainly just sleeping. Have a good week.’(Giles)

Giles was an example of a student struggling with home schooling, and he was also grateful for having an opportunity to speak with other students during the research period. According to him, one of the positive aspects was ‘bouncing off ideas with people’ and ‘made me reflect on things I do that put me in a better/worse mood. I can now prioritise what to do.’ This feedback highlights the importance of having informal learning activities, peer learning initiatives and social interactions during online learning. These types of activities would improve student’s motivation to learn and compensate the isolation feelings.

The quality of the WIFI connection would be the main vehicle to connect students to learn and to interact to each other. In some cases, this would be an additional source of stress. Most students reported bad quality WIFI connection, particularly because other members of the household were using it as well ‘my mother works from home and we share the same working space’ (Lara). Having most of the activities delivered online with few interruptions was not helpful and required extra demand from WIFI connection.

Stimulating aspects of home learning

Some students would carefully consider the physical characteristics of their learning spaces. While moving from one place to another around the house, several participants mentioned the importance of having natural light in their HLE:

My desk is right next to two large windows which is good for giving me light whilst working, I feel more motivated when it is bright. (Katie)

I can get some natural light in. (…) I much prefer this to the darkness and artificial lightning of the other learning space. (Claire)

Natural light from above as having a well-lit environment helps me in thinking and it makes locating things easier. I find that a blue sky and sunny weather uplifts my mood and motivates me to complete my assignments. (Saylah)

Several students identified small elements next to their working area that helped them to relax and keep calm, e.g. candle, diffuser with lavender scent (Anna), something to pray with and a stress ball (Shanice), plants (Robert), small waterfall in the garden (Lara). Having their personal objects in their HLE would make them feel more comfortable, balanced and focused.

Considering their home learning routines, some of the participants mentioned a social interaction/physical activity outdoors with their household, e.g. walk their dogs and/or go for a walk on the neighbourhood with their family members. These activities helped connect them to the outside world and compensate for the lack of commuting time from home to school.

Comparing HLE and school learning environment (SLE)

If HLE and SLE routines are compared, the routines during lockdown seemed more fluid and relaxed, with a reduced teaching schedule and more time for independent study. ‘Even when my routine from formed trends, such as waking up at similar times every day, these trends shifted from week to week, meaning that even from the moment I woke up, there was a fractured, unsettled nature to my routine’ (Oliver). During lockdown, most of the participants were ‘looking forward to be back to school’ (Jemima) and would prefer to be back to school because the felt disorganised (Molly). Only a few participants would like to go back to a blended mode with some days working from home and some days working from school because they would spend too much time in commuting, and this intermediate solution would allow them use their time more effectively.

While reflecting on their HLE during COVID-19 pandemic, most participants recognized the value of commuting from home to school every day,

Losing the journey to school, it would seem, gives you more hours in the day. In truth, this in an unrealistic view that treats this as a merely functional time of the day. The journey from home to school allows you to reset your mind, to enter a space you recognise from an early age as a space to learn. Being in my thirteenth year of education, this steadfast, deeply rooted, daily transition is not one I ever expected to lose. (Oliver)

Commuting time was seen as reset time, not only as time to move from one space to another but also as a reset time, a period to unwind and keep a routine. For Shanice, ‘seeing people outside from my window makes me miss college life especially since I used to walk there and comeback’.

Young people recognised the importance of social interactions to enhance learning. School was not only seen as a physical learning space but rather a learning community, where teachers and pupils came together and where social interactions were essential.

I learned during this pandemic that it is not just the space in which we produce work, but the people orbiting us that also drives us and help to complete a learning space (…) the spaces where we learn in, regardless of whether they are in a formal educational setting or at a homemade (IKEA) desk, require a degree of human contact, or maybe just proximity to others. Fundamentally, I believe that it is part of human nature to be motivated and driven by each other, perhaps even to the point of envying others and their fastidious dedication. (Oliver)

This statement reveals how learning spaces can only be fully mapped if we consider them as socio-material units. More than physical settings, teaching and learning approaches, the social relationships and the community of practices have an impact on young people’s motivations.

Most of the students missed in-person teaching, peer learning activities and social interactions:

Definitely miss being in face-to-face lessons because I learn better with social interactions. (Katie)

Missing being at the college and seeing my friends. (Jessica)

Missing people, chemistry lab practices and classroom contact lessons. (Olivia)

Discussion

The impact of home learning environment on young people’s learning motivations

This study mapped several physical home learning environment spaces and tools that have an impact on young people’s learning motivation. I also found that the combinations of specific physical environment characteristics led to even stronger associations between the physical HLE and the learning motivation.

The location and settings of HLE within the house have an impact on young people’s motivations. Through my research, I was able to carefully map and characterize these physical spaces and understand their physical characteristics. On the one hand, if pupils dedicated space to learn (e.g. desk in their bedroom and/or office), they were able to focus and feel productive. On the other hand, if they have to share spaces (e.g. shared bedroom/desk) or need to adapt the HLE to household dynamics (e.g. working at the dining table) they struggle to concentrate. This spatial inequality has been already identified by Azhari and Fajri (Citation2020), Lamb et al. (Citation2020), Sibanda and Mathwasa (Citation2021) and Yates et al. (Citation2020) as gaps in basic resources of families needed to support home learning, the material divide. Research evidence shows that learning experience was further improved if learners have affixed learning place that does not required to be coordinated/shared with others (Aschenberger et al., Citation2022).

The closure of schools in response to the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the daily lives, learning experiences of young people and increased educational inequalities (Andrew et al., Citation2020). Pupils from the poorest families were the least likely to have access to the devices needed and internet access from home (Cullinane & Montacute, Citation2020). Participants had access to an internet connection and (at least) one device to attend lessons online during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, different types of devices (e.g., Mobile Phone, Tablet, Laptop and Personal Computer) provide different learning opportunities. Students with additional tools (e.g., printers, digital pens) were able to complete their assignments more effectively. In this sense, the social inequalities and ability to learn are more evident at the HLE that at the SLE. On one hand, at the HLE, not every student has a dedicated space where they can optimize their learning. On the other hand, the SLE is accessible to everyone and create a more inclusive environment and provides similar opportunities to all.

According to Aschenberger et al. (Citation2022), their participants did not make a connection between learning place and learning experience; however, they would recognise the influence of the spatial learning situation on concentration. My findings show that young people acknowledge the impact of HLE on their learning motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. This has been also reported in a number of studies where the cumulative impacts of low motivation increase disengagement and loss of learning (Bond, Citation2020; Cayubit, Citation2022). In my study, this is particularly evident when comparing the HLE with the SLE. At home, most of the participants had an individual learning space with few social learning interactions. However, being in the same room all the time would drop their learning motivation levels to the point of being down and sleeping constantly. For other students, the lack of dedicated learning spaces at home and difficult to have somewhere to do write/do their learning activities would create a bigger gap between the learning experience and home and at school. The lack of connection, social interactions and online teaching/learning challenges were also some of the most difficult aspects reported by teachers during the pandemic (Baker et al., Citation2021).

At school, the learning space is shared and in this sense the peer pressure and social interactions enhance learning. Schools consider the organizational conditions that make teachers work and students learning possible (Kraft et al., Citation2020) and young people recognised the value of school as a learning organisation (Kools & Stoll, Citation2016) where ‘a “learning atmosphere”, “learning culture” or “learning climate” is nurtured; and where “learning to learn” is essential for everyone involved’ (OECD). Without the in-person daily interactions within the classroom and/or school, teachers may have less capacity to see how their students are coping and adjust their practices accordingly (Lamb et al., Citation2020). This issue could potentially be minimised by encouraging teachers to map the individual HLE and identify the key characteristics of the spaces and tools used for learning. By doing this, the assignments and teaching activities could be adjusted to the resources available and reduce some of the identified inequalities.

The reliable rhythms of commuting to school would create a learning routine and a predisposition to learn. Most participants missed the commuting time between home and school, the breaks between classes and the informal social interactions at school. This acknowledges the importance of physical learning environments to support innovative pedagogies and students’ experiences (Baars et al., Citation2022). By acknowledging this, the future home learning activities could consider a timetable that includes longer breaks, soft learning and offline learning activities. This strategy would help to improve the home learning experience and physical activity ate the HLE and well.

Most of participants demonstrated a full awareness of side effects of screen time and lack of physical activity. Some participants would try to go for a walk with a family member and/or do some exercise by the beginning/end of the day. This relationship between the home environment and young people’s physical activity has been addressed previously in various studies (Maitland et al., Citation2013; Sirard et al., Citation2010; Tandon et al., Citation2014) and established associations between the home environment and adolescent physical activity, sedentary time, and screen time. The COVID-19 pandemic was not favourable since students were asked to spend extra screen time with fewer breaks.

By recognizing the importance of HLE not only during COVID-19 pandemic but as an extension of young people’s SLE (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020), mapping the HLE helps us to understand the transition between different learning environments and support young people’s learning journey.

Bond, et al. (Citation2021) report that students were more motivated to learn and complete school work during pandemic, referencing an increased ability to study and problem-solve independently, as well as an improved sense of responsibility. This was not reflected on my sample, and I couldn’t find an increase of motivation during COVID-19 lockdown periods. Hong (Citation2001) refers the importance of parental involvement in the home learning environment to enhance student’s motivation. However, in this study was not identified parent-motivated attitudes, most likely because participants are 16–18 years old and are independent learners.

According to Joosten and Cusatis (Citation2020) and Zhang and Lin (Citation2020), the learning motivation at home depends, in part, on specific qualities of young people. Students that are motivated, independent and self-directed tend to perform well on online learning activities. Through my research, I could also confirm that the students with a more positive approach, showing the capacity to persevere towards a goal (Duckworth et al., Citation2007), despite the adverse circumstances caused by COVID-19 pandemic, were the ones taking the ownership of their HLE and changing the environment to maximise their learning performance (e.g., revision posters, timetables, to do lists around their HLE).

In some cases, the home-schooling experience during the COVID-19 pandemic was well received by the school community, parents, pupils and teachers. ‘There was more creative learning, better progress, more useful feedback and greater student experience’ (Bubb & Jones, Citation2020, p. 209). According to this study, despite two participants that would like to move to blended learning and reduce their commuting time, most of participants did not find the online learning experience positive and would rather prefer to go back to in-person teaching. Similarly to other research (Bhamani et al., Citation2020), young people that took part in this study were missing the social interactions and considered this an essential element of their learning journey. Consequently, being in the HLE instead of SLE would affect their learning motivation, as they valued the opportunity to interact in-person with their teachers and peers.

Only few participants engaged with the physical dimensions of the HLE (spaces and tools for learning) and change them to increase their learning motivation. This was particularly difficult for the students with shared HLE because they had less control over the space. For the ones that had private HLE, only few of them were appropriating the spaces and actively adjusting their spaces and tools according to their learning needs. The perceived affordances are based on the interactions between the participants and their physical environment (Jones, Citation2003). Participants who analysed architectural affordances and reflect on how to improve their learning spaces had a better control of the HLE and were the ones able to adjust their learning spaces according to their needs. This is aligned with previous research done, where the more students ‘perceived that their physical learning environment was meeting their needs, the higher were their motivation and well-being and the lower was their stress’ (Aschenberger et al., Citation2022). By providing a reflexion where students identify the key physical dimensions of a good HLE would help them to adjust it according to their needs.

Conclusion

According to this study, the HLE influenced young people motivation to learn during the COVID-19 pandemic. The physical dimensions of the HLE (Learning tools, and Learning Spaces) can support and/or challenge young people’s learning journey. By considering and adjusting the physical dimensions of the HLE, we may be able to better understand student’s behaviours and support students’ academic achievements.

This research analysed the physical dimensions of the HLE and mapped the aspects causing disruption and stimulating the home learning. Students that adjusted the physical dimensions of the HLE were more motivated, especially if they had a private, semi-dedicated, or dedicated HLE. However, further research is requested to contextualise the physical dimensions of the HLE and comprehend the implications of the wider social, cultural and physical aspects. The physical HLE is part of a house, within a neighbourhood, with in a city. This research highlights the potential of the physical dimensions of the HLE, presents the different home learning spaces and tools, these can be used to structure further research in this area and measure young people’s motivation to learn. Furthermore, according to this research, the home-schooling experience during the COVID-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to re-imagine HLE as a complementary learning environment to SLE, motivate young people to learn and support independent learning activities.

Given the associations I found between the spaces and tools for learning available and physical environment variables, I highlight the need to better address these factors, support further adjustments and enhancement of the HLE:

Map the individual HLE and identify the key characteristics of the spaces and tools for learning;

Design/adjust the online/independent teaching/learning activities according to the individual characteristics of the HLE;

Map best practices to create a motivational HLE (e.g. spatial appropriation, use of analogue visual aids, acknowledge personal preferences) and share them among students.

These measures would help us to support young people with low-quality HLE and promote further synergies between the HLE and the SLE. However, only two students would like to move to a blended learning mood to reduce their commuting time and all participants involved would prefer to go back to in-person teaching because they did not find the online learning experience positive. Therefore, reflecting on the COVID-19 pandemic experience we can innovate and re-imagine the role of the HLE as a complementary learning environment to school and to support independent learning opportunities. This is particularly important with older pupils, to develop independent learning habits and to support their transition to higher education/professional market and learning journey.

Limitations

Online vs in-person data collection

The students from school A who attended the FGD online presented more careful and well annotated illustrations. However, the online discussion was limited, as they preferred to work individually. Participants preferred to keep their cameras off and communicate via Microsoft Teams chat. The research participants from school A saw this activity as an extra assignment and an opportunity for self-reflection. On school B, the FGD were more interactive. Participants shared their views and explained their drawings in-person and these generated a discussion. However, their final illustrations were less elaborated and with fewer annotations. They wouldn’t add any further details after the in-person group discussion. Some students opted to share their contributions only via text without using any illustrative photographs/drawings. In these cases, the text was carefully written, presented as a self-reflective piece.

The use of mobile phones to take pictures of the HLE

The students that produced annotated photographs to illustrate their HLE did not include their mobile phones as part of their HLE because these were used to take the photographs. The act of photographing with phones led to their omission from participants. Despite not having phones featured on the annotated photographs, the complementary data collected during the FGD gave students the opportunity to explain the use of mobile phones as a learning tool and therefore, part of their HLE. In future, while using a similar data collection method, to avoid the lack of reflection on mobile phones’ role I would suggest this could be included on the annotations.

Ethics approval

Lancaster University, FASS & LUMS Research Ethics Committee & UREC. Ethics approval reference FL20057.

oaed_a_2322862_sm9818.docx

Download MS Word (45.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all participating young people, their teachers and their schools engaged in the data collection for their most active cooperation and thoughtfulness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ana Rute Costa

Ana Rute Costa is an architect and an educational researcher with a strong specialism in Learning and Teaching spaces. Her research and professional practice focuses on analysing the impact of the built environment in teaching and learning through ethnographic and visual research methods. She specialises in policies and practices that affect the design of spaces and products that enable learning to take place.

She is also the Course Leader for the BA (Hons) Architecture at Lancaster University and certified Passivhaus Designer, fostering to create dynamic links and knowledge exchange between academia and architectural practice. She is an expert on Material Reuse and Material Passports and she has several research projects funded in this area.

Photo of the author(s), including details of who is in the photograph - please note that we can only publish one photo

Notes

1 Timeline of the UK coronavirus lockdowns and measures between March 2020 and December 2021 available here: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns.

References

- Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., Phimister, A., & Sevilla, A. (2020). Inequalities in children’s experiences of home learning during the COVID-19 lockdown in England. Fiscal Studies, 41(3), 653–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12240

- APA. (2020). The publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

- Aschenberger, F. K., Radinger, G., Brachtl, S., Ipser, C., & Oppl, S. (2022). Physical home learning environments for digitally-supported learning in academic continuing education during COVID-19 pandemic. Learning Environments Research, 26(1), 97–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-022-09406-0

- Azhari, B., & Fajri, I. (2020). Distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: School closure in Indonesia. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 53(7), 1934–1954. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2021.1875072

- Baars, S., Schellings, G. L., Joore, J. P., & Wesemael, P. J. (2022). Physical learning environments’ supportiveness to innovative pedagogies: students’ and teachers’ experiences. Learning Environments Research, 26(2), 617–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-022-09433-x

- Baker, C. N., Peele, H., Daniels, M., Saybe, M., Whalen, K., Overstreet, S., & The New Orleans, T.-I S. L. C. (2021). The experience of COVID-19 and its impact on teachers’ mental health, coping, and teaching. School Psychology Review, 50(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855473

- Banks, M. (2018). Using visual data in qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

- Banks, M., & Zeitlyn, D. (2015). Visual methods in social research. SAGE Publications.

- Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment, 89, 118–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.02.013

- Bell, P. (2004). Content analysis of visual images. In T. V. Leeuwen & C. Jewitt, The book of visual Analysis (pp. 10–34). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020062.n2

- Bhamani, S., Makhdoom, A. Z., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N., Kaleem, S., & Ahmed, D. (2020). Home learning in times of COVID: Experiences of parents. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v7i1.3260

- Bond, M. (2020). Schools and emergency remote education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A living rapid systematic review. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 191–247. http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/517

- Bond, M., Bergdahl, N., Mendizabal-Espinosa, R., Kneale, D., Bolan, F., Hull, P., & Ramadani, F. (2021). Global emergency remote learning in secondary schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute.

- Bradley, R. H., Pennar, A., Fuligni, A., & Whiteside-Mansell, L. (2019). Assessing the home environment during mid- and late-adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 23(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1284593

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Bubb, S., & Jones, M.-A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improving Schools, 23(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480220958797

- Cayubit, R. F. (2022). Why learning environment matters? An analysis on how the learning environment influences the academic motivation, learning strategies and engagement of college students. Learning Environments Research, 25(2), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09382-x

- Chen, A. T. (2018). Timeline drawing and the Online scrapbook: Two visual elicitation techniques for a richer exploration of illness journeys. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 160940691775320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917753207

- Chiu, B., & Lapeyrouse, N. (2021). Student experiences and perceptions of emergency remote teaching. ACS Symposium Series, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2021-1389.ch009

- Cullinane, C., & Montacute, R. (2020). COVID-19 and social mobility impact brief #1: School closures (S. Trust, Ed.). Research Brief.

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

- Evans, G. W. (2006). Child development and the physical environment. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 423–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190057

- Evans, J., & Hall, S. (1999). Visual culture: the reader. SAGE Publications.

- Feinstein, L. (2003). Inequality in the early cognitive development of British children in the 1970 cohort. Economica, 70(277), 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.t01-1-00272

- Feller, A., & Stuart, E. (2021). Challenges with evaluating education policy using panel data during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14(3), 668–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2021.1938316

- Niklas, F., Cohrssen, C., Lehrl, S., & Napoli, A. R. (2021). Editorial: Children’s competencies development in the home learning environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 706360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.706360

- Fukumura, Y. E., Schott, J. M., Lucas, G. M., Becerik-Gerber, B., & Roll, S. C. (2021). Negotiating time and space when working from home: Experiences during COVID-19. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 41(4), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492211033830

- Gibbs, G. (2007). Analysing qualitative data. SAGE.

- Hicks, A., & Lloyd, A. (2018). Seeing information: Visual methods as entry points to information practices. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769973

- HM Government, H. (2018). Improving the home learning environment: A behaviour change approach. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-the-home-learning-environment

- Holt, L., & Murray, L. (2021). Children and Covid 19 in the UK. Children’s Geographies, 20(4), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1921699

- Hong, E. (2001). Homework style, homework environment and academic achievement. Learning Environments Research, 4(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011458407666

- Jones, K. S. (2003). How shall affordances be refined? Four perspectives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203726655

- Joosten, T., & Cusatis, R. (2020). Online learning readiness. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(3), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1726167

- Kearney, K. S., & Hyle, A. E. (2004). Drawing out emotions: The use of participant-produced drawings in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Research, 4(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104047234

- Kools, M., & Stoll, L. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisations?. (O. Publishing, Ed.) OECD Education Working Papers., No. 137. https://doi.org/10.1787/19939019

- Kraft, M., Simon, N., & Lyon, M. A. (2020). Sustaining a sense of success: The protective role of teacher working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14(4), 727–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2021.1938314

- Lamb, S., Maire, Q., Doecke, E., Noble, K., Pilcher, S., & Macklin, S. (2020). Impact of learning from home on educational outcomes for disadvantaged children. Retrieved from https://www.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/impact-of-learning-from-home-federal-government-brief-mitchell-institute.pdf

- Lehrl, S., Ebert, S., Blaurock, S., Rossbach, H.-G., & Weinert, S. (2020). Long-term and domain-specific relations between the early years home learning environment and students’ academic outcomes in secondary school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1618346

- Lehrl, S., Evangelou, M., & Sammons, P. (2020). The home learning environment and its role in shaping children’s educational development. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1693487

- Lister, M., & Wells, L. (2004). Seeing beyond belief: Cultural studies as an approach to analysing the visual. In T. V. Leeuwen, & C. Jewitt (Eds.). The handbook of visual analysis (pp. 61–91). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020062.n4

- Maitland, C., Stratton, G., Foster, S., Braham, R., & Rosenberg, M. (2013). A place for play? The influence of the home physical environment on children’s physical activity and sedentary behaviour. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-99

- Melhuish, E. C., Phan, M. B., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2008). Effects of the home learning environment and preschool center experience upon literacy and numeracy development in early primary school. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00550

- Nagib, W., & Williams, A. (2017). Toward an autism-friendly home environment. Housing Studies, 32(2), 140–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1181719

- Nampijja, M., Kizindo, R., Apule, B., Lule, S., Muhangi, L., Titman, A., Elliott, A., Alcock, K., & Lewis, C. (2018). The role of the home environment in neurocognitive development of children living in extreme poverty and with frequent illenesses: A cross-sectional study. Wellcome Open Research, 3, 152. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14702.1

- Niklas, F., Nguyen, C., Cloney, D. S., Tayler, C., & Adams, R. (2016). Self-report measures of the home learning environment in large scale research: Measurement properties and associations with key developmental outcomes. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-9206-9

- Niklas, F., Tayler, C., & Schneider, W. (2015). Home-based literacy activities and children’s cognitive outcomes: A comparison between Australia and Germany. International Journal of Educational Research, 71, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.04.001

- OECD. (2021). Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/supporting-young-people-s-mental-health-through-the-covid-19-crisis-84e143e5/

- Pain, H. (2012). A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(4), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691201100401

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. SAGE.

- Rawat, C., & Gulati, R. (2019). Influence of home environment and peers influence on emotional maturity of adolescents. Integrated Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 15–18.

- Salmons, J. (2014). Visual methods in online Interviews. Sage Research Methods Cases. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4135/978144627305014527692

- Sammons, P., Toth, K., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj, I., & Taggart, B. (2015). The long-term role of the home learning environment in shaping students’ academic attainment in secondary school. Journal of Children’s Services, 10(3), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-02-2015-0007

- Sibanda, L., & Mathwasa, J. (2021). Perceptions of teachers and learners on the impact of Covid-19 pandemic lockdown on rural secondary school female learners in Matoba District, Zimbabwe. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 6(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejsss.v6i3.1029

- Sirard, J. R., Laska, M. N., Patnode, C. D., Farbakhsh, K., & Lytle, L. A. (2010). November) Adolescent physical activity and screen time: Associations with the physical home environment. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 28(11), 1419–1427. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/28.11.1419

- Spawforth-Jones, S. (2021). Utilising mood boards as an image elicitation tool in qualitative research. Sociological Research Online, 26(4), 871–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780421993486

- Sullu, B. (2023). Children’s access to play during the COVID-19 pandemic in the urban context in Turkey. Children’s Geographies, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2023.2195046

- Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., & Siraj, I. (2015). Effective preschool, primary and secondary education project (EPPSE 3-16+). Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_d

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Luo, R., McFadden, K. E., Bandel, E. T., & Vallotton, C. (2019). Early home learning environment predicts children’s 5th grade academic skills. Applied Developmental Science, 23(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.13

- Tandon, P., Grow, H. M., Couch, S., Glanz, K., Sallis, J. F., Frank, L. D., & Saelens, B. E. (2014). Physical and social home environment in relation to children’s overall and home-based physical activity and sedentary time. Preventive Medicine, 66, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.05.019

- Toth, K., Sammons, P., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj, I., & Taggart, B. (2019). Home learning environment across time: The role of early years HLE and background in predicting HLE at later ages. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1618348

- United Nations. (2021). The sustainable development Goals report 2021. United Nations.

- Vaquera, E., Jones, R., Marí-Klose, P., Marí-Klose, M., & Cunningham, S. A. (2018). Unhealthy weight among children in Spain and the role of the home environment. BMC Research Notes, 11(1), 591. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3665-2

- Yates, A., Starkey, L., Egerton, B., & Flueggen, F. (2020). High school students’ experience of online learning during Covid-19: The influence of technology and pedagogy. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1854337

- Zhang, Y., & Lin, C.-H. (2020). Motivational profiles and their correlates among students in virtual school foreign language courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(2), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12871