ABSTRACT

This paper introduces the Feral Map, an open online map that brings together different creative practices questioning the dominant extractive, technocentric rendering and legitimising of particular algorithmic futures. Building on its initial development drawn upon open urban tree data, it invites people to explore and engage with their surroundings in creative, unfamiliar ways and share their experiences in the form of stories, using different kinds of media, sensory impressions, and personal expressions. These stories can be offered to existing places and local “creatures” (such as animals, ambiences, and glitches) or become new creatures on their own, emphasising mattering and entanglements: that change is the only constant in life. Through this, the map obscures the currently available – mostly quantitative – data about a place, and can help to raise questions about power, values, and structural inequalities that shape the place and its future. The Feral Map has been evolving to include such stories and creatures – or messy data – from different creative, practice-based research projects. Our paper presents the theoretical framing of the Feral Map and its design, how it has been transforming along with the involved projects, as well as our learnings from the process and possible future directions.

RÉSUMÉ

Ce papier présente la Carte Sauvage - la Feral Map - une carte en ligne à accès libre, qui rassemble différentes pratiques créatives, et questionne le rendu dominant et la légitimation – extractifs et technocentriques – de certains futurs algorithmiques. S'appuyant sur son développement initial à partir de données ouvertes sur les arbres urbains, elle invite les gens à explorer et à s'engager dans leur environnement de manière créative et inhabituelle et à partager leurs expériences sous forme d'histoires, en utilisant différents types de médias, d'impressions sensorielles et d'expressions personnelles. Sur la carte ces histoires peuvent être associées à des lieux existants ou à des « créatures » locales telles que des arbres, de la mousse, des chalets, des marteaux piqueurs utilisés lors de la construction de routes, ou devenir elles-mêmes de nouvelles créatures, soulignant que “la matière elle-même est toujours déjà ouverte à l'”autre“, ou plutôt enchevêtrée avec lui” (Barad, 2007). Grâce aux points et données associées ajoutés par les participants, la carte masque les données collectées et disponibles – essentiellement quantitatives – sur un lieu particulier, et peut contribuer à soulever des questions sur le pouvoir, les valeurs et les inégalités structurelles qui façonnent le lieu et son avenir. La carte sauvage a évolué pour inclure des histoires et créatures – ou des données désordonnées – issues de différents projets de recherche, dont les projets Open Forest, Open Urban Forest et Secret. Notre papier présente le cadre théorique de la Carte Sauvage et sa conception, la façon dont elle a été transformée avec les projets impliqués ainsi que les enseignements que nous avons tirés du processus et les orientations possibles pour l'avenir.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

‘Where are we?’ means two things at once: ‘how can we characterize the situation in which we live, think and act to-day?’, but also, by the same token: ‘how does the perception of this situation oblige us to reconsider the framework we use to “see” things and map situations, to move within this framework or get away from it?’; or, in other words, ‘how does it urge us to change our very way of determining the coordinates of the “here and now”?’ (Rancière, Citation2009)

Made off. Don’t stray. Well, my kind’s your kind. I’ll stay the same. Pack up. Don’t stray. Oh say, say, say. (Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Citation2003)

As Keith and Pile (Citation1993) argue, ‘the thoroughly naturalized absolute conception of space … expresses a very specific tyranny of power,’ forming ‘quite literally the space of capitalist patriarchy and racist imperialism [which thus] should hasten critique and reconstruction’ (p. 74). One ongoing attempt in propelling such critique is critical feminist GIS (Geographical Information Systems) as scholarship and practice. Its development has been continuous and contiguous to the epistemological discord between GIS practitioners and their critics particularly in human geography during the so-called ‘science wars’ in 1990s (Schuurman, Citation2000, p. 570). Central to this was problematising the dominant positivist episteme and focus on quantitative techniques, which help legitimise the aforementioned ‘absolute space’ while limited attention is given to the co-evolution of science and culture (Haraway, Citation1988; Latour, Citation1993), which would require critical questioning about how data or truths may be made. Reflecting on this continued contestation, Schuurman and Pratt (Citation2002) call for action to move beyond the binary contestation and instead take a generative approach to care by taking more of an additive empiricist (Latour, Citation2016) approach to collaboratively question how GIS operates as a knowledge system.

The positive impact of coalescing disciplinary perspectives and practices has been evident in a wide range of new, creative-critical approaches to GIS and more broadly cartography questioning socio-political power relations emerging in recent years, such as narrative cartography (Caquard & Cartwright, Citation2014), inefficient (Knight, Citation2021), as well as emotion and sensory (Goffe, Citation2020; Griffin & McQuoid, Citation2012) mapping. While new technological capacity led to new possibilities – for example, being able to see oneself on a map in real-time or what Greenfield referred to as ultramapping (Greenfield, Citation2010) – challenges that had previously been less visible also surfaced. For example, Elwood’s (Citation2001) study on a neighbourhood association in Minneapolis showed that while GIS can foster community autonomy and influence in urban governance, it can also create barriers to community participation by reinforcing the state’s planning discourse.

As the authors of this paper, we come from and move across different creative domains in art, design, and technical development with shared aspirations for eco-social change towards liveable futures. Mapping is a common undertaking in our practices and manifests in various forms at different stages – for example, in the so-called ‘fuzzy frontend’ to survey the possible creative directions, to examine data flows, and to speculate interactions and experiences with creative output. One common aspect of our diverse engagements with mapping is that they are often done collaboratively with generative intentions for enacting further collective action and imagination. Mapping thus functions as a co-creative tool and method in our work. Particularly through the COVID-19 pandemic, similar approaches to mapping became a familiar feature of the growing remote collaboration, aided by online visual collaboration platforms such as Miro (miro.com), Mural (mural.co), and Figma (figma.com). These platforms offer different generative temporalities: some are used in a singular gathering and are not accessed again after; others continue to be used as a living archive or repository (for example, how Miro was used as an extension of a written text inviting ongoing open contributions to expand its key concepts – see Choi & Botero, Citation2021).

Over time, the outcomes of these collaborations can become what Australian anthropologist and futurist Genevieve Bell (Citation2010) calls feral data and technologies. Bell’s use of the term was in reference to animals such as camels and rabbits that were brought to Australia by British colonisers in the late eighteenth century to serve specific purposes, such as transportation and entertainment. These once domesticated animals were ‘forgotten’ subsequently to the end of their perceived instrumental usefulness – for example with the introduction of locomotives superseding camels as the preferred form of transportation across the vast, dry lands. However, these animals later returned to human attention as feral creatures whose lifeways became concurrently familiar and unfamiliar to humans, impacting local humans and others in unexpected ways. Some of these creatures were then deemed pests and predators and subjected to violent mass culling through the use of different technological instruments. Although Bell does not explicitly make connection to the term More-than-Human (MtH), the notion of feral provides a conceptual space in and through which we might consider and experiment with MtH entanglements involving humans and other-than-humans – for example, multispecies and algorithmic agencies – and question the differential power relations inherent in their formation. What may be useful can become a pest or peril for human infrastructures, largely built and maintained with anthropocentric intentions. As compared to pest or peril, the term feral helps move beyond the definitive space of the Other and instead opens the conceptual in-between space that can help challenge the dominant normativity, engendering a potential for change by highlighting that in more-than-human entanglements ‘change is the only constant, and that transformation lies around every turn’ (Choi et al., Citation2023).

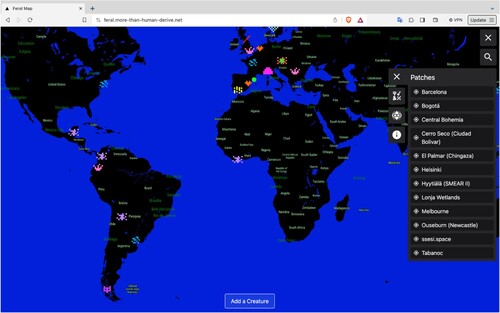

Our ongoing online project, the Feral Map (https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/) materialised in this spirit of entanglements and has been evolving with multiple inertias arising from our transdisciplinary experimental aspirations to understand and move beyond arbitrary boundary conditions – sociotechnical, disciplinary, and more – to open and (re-)mix relational spaces for creative-critical experiments. These involve, for example, experimentation with data and MtH more-than-human lifeways in different places. It is our hope that these in-between, relational spaces can help us generatively question, rather than simply critiquing, the dominant systems of power to move towards more just and liveable futures. In our entanglements with the Feral Map, we also respond to Schuurman and Pratt’s (Citation2002) call for inviting more perspectives and experiences and directly engaging with technologies and possibilities they enable. As such, the Feral Map is messy – technically, conceptually, visually, and in many other ways. It is always in-flux and remains open to different, often unexpected, needs, desires, knowledge, and practices emerging from our own entangling with the Feral Map and others connected through it ().

In this paper, we will first describe the Feral Map, including its beginnings, qualities, and uses. We will then discuss and provide examples of how it has been co-evolving in different relations and entanglements with diverse creative projects, highlighting the need to embrace the messiness arising from the many differences revealed through the process of entangling. This will be followed by outlining the Feral Map’s three key qualities that are inter-related and illustrative of its feral, shapeshifting nature, then a brief discussion about its future directions underpinned by the possibilities and perils that feral practice might entail in challenging the dominant extractive, technocentric rendering and legitimising of particular algorithmic futures.

History of the Feral Map

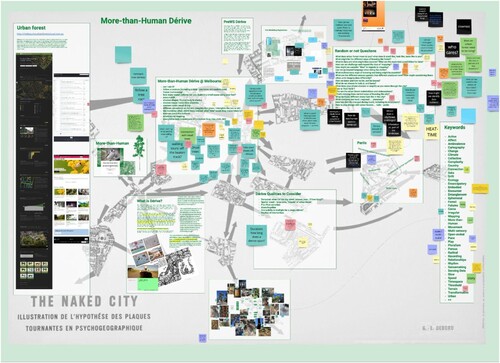

The Feral Map came into being as part of the More-than-Human (MtH) Dérive (https://more-than-human-derive.net/about/), a participatory project and online portal inviting people to drift or take a dérive – an unplanned journey through local landscapes. The first dérives using the portal took place in the Melbourne Urban Forest: a complex ecosystem of over 70,000 trees in inner-city Melbourne, each assigned with a unique digital ID and associated with various open datasets. The online portal consisting of the Feral Map and the MtH Dérive was initially developed through three online co-creative workshops with scientists, designers, artists, researchers, and policy actors from Melbourne during the height of the local COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. In itself designed as a virtual dérive using a Miro board with various drifting ideas, the workshops invited participants to explore and freely respond to or expand on the questions and provocations provided on the Miro board (). The board also included various details such as the information about the Melbourne Urban Forest; history of the dérive including its characteristics, perils, and possibilities as a method, concept, and strategy; snapshots from small dérives which the workshop facilitators had undertaken prior to the workshop; related concepts and keywords, and; ideas for further dérive prompts.

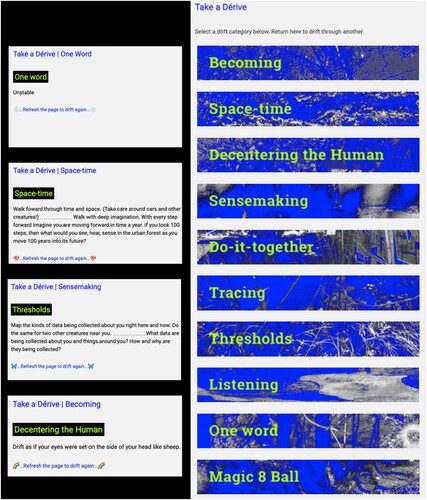

Informed by the workshop outcomes, over 200 creative prompts for drifting through the local landscape were created and categorised into 10 themes () including Becoming (To listen and attune to those less visible or heard), Space-time (To understand space and time differently), Decentering the Human (To not assume anthropocentrism and human exceptionalism), and Sensemaking (To feel, think, and know differently).

MtH Dérive takes inspiration from the Letterist and Situationists International’s artistic strategy of Dérive (drifting), inviting walkers to take an unplanned psychogeographic exploration through a landscape, during which they are expected to drop their everyday relations and let themselves be drawn by chance encounters with varied ambiances (Debord, Citation1958). Dérives challenged the restrictive spaces created by the social and architectural conditioning in urban environments and aimed at creating new spaces for movement and action through creative, playful interactions with abstract intentions. Often, dérives involved creating abstract maps. As Cosgrove (Citation2005) describes, ‘Thought of cartographically, the dérive was a conscious challenge to the apparently omniscient, disembodied and totalizing urban map that had become the principal instrument for urban planning and “comprehensive redevelopment” during the postwar years.’ Similarly, the Feral Map provides a space that makes visible the participants’ diverse experiences with the city, some of which are enabled through the MtH Dérive. On the map, these experiences can be expressed in various forms, such as Creatures and Stories.

The design and engagement with the Feral Map were also inspired by the City of Melbourne’s existing Urban Forest Visual website (melbourneurbanforestvisual.com.au), which draws on the Melbourne Urban Forest dataset and invites people ‘to explore this dataset and some of the challenges facing Melbourne’s Urban Forest.’ The main feature of the website is an interactive map that provides selected information about each mapped tree, including its scientific name, age, and tree ID. Along with this information, there is a button for visitors to email the trees. While it is understood that initially this feature was added to provide an alternative channel for local citizens to submit reports to the city officials about the trees – for example, damaged branches and other visible concerns – its principal and unexpected use has been by people around the world writing letters to the trees rather than about them, many expressing affection and appreciation for, and personal memories about them. These letters are the very stories that make the larger narrative not only of the tree but also the urban forest and more broadly the city itself, and should thus be considered critical data to inform decisions about them. However, they remain illegible to the knowledge and algorithmic systems that only feed specific sets of official, scientific data into their operation. With the Feral Map, we hope to acknowledge the many ways people relate to a particular place and the importance of the different ‘messy’ yet critical data in collective imaginings of the past, present, and the future. The map draws attention to the forgotten banality of how the familiar and unfamiliar always coexist and coevolve, an aspect largely ignored by the dominant systems of power and knowledge. In the next section, we detail the key features of the Feral Map.

Stories on the Feral Map

In its current version, the Feral Map is visually formed by the relations of five primary data layers as shown below:

Base layer provides the visual context and is largely made up of a curated selection of geographic information layers provided by the proprietary application MapBox (https://www.mapbox.com/). The layers may include information such as the names and coordinates of streets, rivers, mountain ranges, political borders, and other points and conditions of interest, and are visualised as ‘tiles.’

External Data layer is then added to the Base layer. The layer includes data generated automatically using various existing, open and publicly available datasets. For example, the Urban Forest Tree data sourced from the City of Melbourne’s Open Data Portal (https://data.melbourne.vic.gov.au/) form an external data layer, enabling the mapping of each of the 70,000 trees onto the tiles.

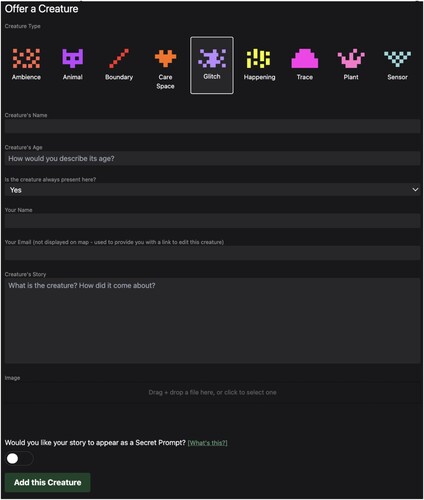

Creatures layer is generated by the data contributed by participants who can add new points of interest to particular locations on the map (). The term Creature is used to denote inclusively what may materialise tangibly/visibly or intangibly/invisibly in specific space-times (e.g. sensors, animals, and ambiance) as observed by the participant.

Patches layer contains information about the areas (or Patches) where associated experimental activities take place, such as the Melbourne Urban Forest where the MtH Dérive initially took place, or the Hyytiälä Forestry Research Station in Finland where we regularly organise experimental walks with the local forest (we will discuss later how these forest walks have shaped the Feral Map). The term ‘Patch’ was selected for its relation to specific forest vocabulary and in acknowledgement of the conceptual tool with the same name proposed by Tsing et al. (Citation2019), used for noticing landscape structure with a particular focus on ‘modular simplifications’ and ‘feral proliferations.’

Stories layer contains the participant-contributed inputs in the form of stories that can be added to any of the existing datapoints in the External Data, Patches, and Creatures layers. These stories can be about anything – for example, they may tell participants’ personal memories, observations, or information related to the local landscape – and are meant to open collective spaces for story-sharing and reflection.

Different kinds of relationality are in play with these data layers, and while they are interconnected, they enable different discursive possibilities for questioning and experimenting. There are the two relational forces that are perhaps most foundational to the Feral Map’s operation: on the one hand is the rigid hierarchy of the data layers prefigured by the underlying technological building block (in this case Mapbox) and; on the other, the open relations created by participants through their Stories related to the datapoints on the External Data, Creatures, and Patches layers.

Hierarchical data relations

The hierarchical nature of the data layers is predefined by the technical context in which they operate, restricting what kinds of data relations can be formed. For example, the Base layer is published by Mapbox and does not offer the possibility for change, additional input, or control of the content beyond certain stylistic elements ranging from toggling on or off the street names to the general visual elements such as colours and textures, despite it being created largely from open data sources such as OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org). As a result, additional data layers (External, Creatures, Patches, and Stories) can only exist within the context of Mapbox’s fixed, proprietary data.

Story relations

Contrary to the above explained predefined hierarchical data relations, story relations are created by participants in open and fluid ways. The Feral Map does not require participant registration to contribute and provides three key modes of interaction: creating and placing a Creature; adding Stories to the existing Patches and Creatures, as well as other existing data points such as the trees from the External Data layer, and; browsing and interacting with the map to explore and view details of these participant-generated points and other content shown on the map. Engaging with most of these processes requires a low level of digital literacy comparable to completing a common online form. Other times, because of the nature and stage of its development, it requires more specific knowledge or administration rights. Below we provide a detailed explanation for each process, including the key concepts that foreground its design:

Offering Creatures in place

The participant can create and offer a Creature anywhere on the map by clicking on the preferred point and completing an online form as shown in . Questions about the new Creature are deliberately open and take account of the participant’s experience. The participant can select from nine different creature types, ranging from the more familiar ones such as an animal or plant to the more abstract ones such as an Ambiance or a Glitch. They can name the Creature, and describe the age and the time when its presence is sensed in the place from their own perspective. They can also add Stories and images related to the Creature. The participant’s name and email address are only used to send an email with a link to edit what they created (the email is not made visible on the map). By offering these new Creatures, the participant creates a crack through which the place can be known in a different way, drawing on their personal and locally situated knowledge. Further, there is an option for the participant to offer the Creature to be integrated into a related artwork called the Secret Project, which we will introduce in the ‘Entangled’ section of this paper.

Stories

Stories can be offered to any existing datapoints on the map across the External Data, Creatures, and Patches layers. All of these datapoints can carry multiple Stories added by different participants at different times. Stories can have various formats and contain text, as well as images, sounds, and links to external sites. For example, a story might be a personal account of the participant’s relationship with a particular tree or place expressed in words and images, while another might document the local forest traditions and mythologies. Carrying one or more Stories over time thus transforms a mere datapoint into a presence with its own evolving (hi)story in place. Stories can also be ‘whispered’ to someone, which involves the map interface emailing the Story content to the named recipient, making it simultaneously public and private (whispered stories are sent privately via email but still made visible to everyone on the map without details about the recipient). The whispering feature carries some deliberate functional restrictions that were designed to provoke participants’ critical reflection. For instance, the whisperer can only select one of the thirty Global Cities as the location of the recipient. The Global Cities are the ‘central places where the work of globalization gets done’ (Sassen, Citation2005, p. 35) and have been expanded into a set of metrics that ‘quantify the extent to which a city can attract, retain, and generate global flows of capital, people, and ideas’ (Kearney, Citation2022, p. 4). This restriction for the whisper recipient’s location on the Feral Map is intended to encourage questions about power, values, and structural inequalities in the global landscape by creating, in many cases, an illusionary distance between the whisper and the recipient. Ambiguities such as this are designed into the map as feral, experimental elements aimed to provoke curiosity and reflection and, as such, do not always come with explanations.

Browsing

The interface uses modified tiles provided by Mapbox and offers what have become the standard navigation interactions such as point-hold-drag to move and click or tap on any visible elements to view further information. As with the Creature types (Plant, Ambiance, Glitch, etc.), some data are deliberately made ambiguous. For example, some Creatures appear in full opacity while others are partially opaque depending on the time of their presence in their locations (e.g. nocturnal, diurnal, always present) as specified by the participant who added them. Similarly, the whispers seem to ‘roam around’ the map and appear in different, random locations each time. These ambiguous aspects remain curiously unexplained in the Feral Map and leave an open space for participants’ own interpretations (we will, however, explain this further in the ‘Shapeshifting’ section).

The hierarchical data relations and story relations simultaneously enable and exclude a variety of new, both functional and conceptual relations that may materialise in messy and entangled ways as the Feral Map continues to evolve. In the next section, we present some of the messy aspects, using as an example the Open Forest project, which has been developing in parallel with the Feral Map from the beginning.

Messy

Embracing messiness, as well as the potential challenges and restrictions that it brings about, has been a deliberate choice in the Feral Map’s design. It is an attempt to creatively cross-pollinate our thoughts and (rather limited) resources with the thoughts and needs of various related projects and their collaborators. One such project is the Open Forest (https://openforest.care/) – an experimental, practice-based inquiry into various forests and more-than-human dataflows that we (authors of this paper) have all been involved in developing, in different capacities. The overlap between the Feral Map and the Open Forest (OF) timelines emerged as a convenient opportunity for us to bring the two projects together and experiment with their possible entanglements.

OF explores how forests and forest data can be produced, thought of, and engaged with otherwise (Escobar, Citation2007): in situated, co-creative ways that consider perspectives of diverse forest creatures and reach beyond extractivist renderings of forests as resources to serve colonialist, neo-liberal agendas. Central to OF is a series of experimental walks organised in various forests around the world, where diverse participants come together to walk-with the forests around them, both in person and online, often with the company of a walking guide (Botero et al., Citation2022). The participants’ experiences during these guided walks become inspirations for their forest stories, which are shared in various formats including workshops, sharing circles, interactive installations, a paper-based catalog, and via the Feral Map. Through the Feral Map and the option for participants to share Stories and Creatures in various forests around the world, the project aims to entangle currently available – mostly quantitative – forest datasets with more messy and eclectic inputs (Dolejšová et al., Citation2023).

In the early development of the Feral Map and OF, we started examining open datasets of various urban forests around the world. We noticed a strong focus on tree data. These datasets typically include various practical information related to a tree, including its common and scientific name, geographic coordinates, and biological attributes such as its genus and age. Some datasets further involve various additional data aligned with the interests of the authorities who commissioned and/or maintained the datasets: one example is the canopy cover, which has become an important indicator for climate-resilient urban planning. Although these datasets are typically used to inform policy making, they are often limited in scope, collecting and storing only particular sets of data about particular things in particular places. For instance, we noticed that in the Melbourne Urban Forest datasets, it is mentioned that the ‘date/year planted’ data assigned to each tree is only ‘accurate for trees planted from 2003 onwards.’ Any dates or years assigned to trees in the dataset prior to 2003 indicated the date the trees were added to the inventory, not when they were planted, which creates a biased representation of the local forest. Further, the ‘useful life expectancy’ datafield would presumably be assessed based on the age of the tree, but this requires knowing the approximate time of its planting. Given that for many trees the age may not be accurately recorded, there is no clear indication on the data – or its meta-data – of what the ‘useful’ may mean, for whom and in what ways ().

Figure 5. Entry point for the Melbourne Urban Forest Patch, showing information about a selected tree and options for viewing or adding Stories the tree may carry.

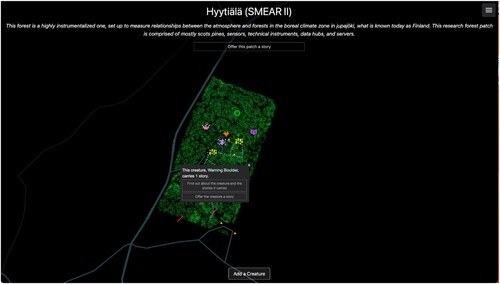

The issue of data being inaccurate or messy is also present in one of our experimental OF Patches, Hyytiälä, which is a highly instrumentalized research forest in Finland. Its open datasets also include entries about the species and age of the local trees, although the age of each tree is less ambiguous than the Melbourne Open Forest, as Hyytiälä was originally a plantation where all mapped trees were planted roughly at the same time. However, the collected data can be messy, for example, with the CO2 exchange occurring between some of the trees and the atmosphere that are used in the calculation on the forest carbon sink capacity. As the station’s data manager reminded us, the CO2 measuring sensors are located in the canopy of trees that are at least 17 m tall, having to survive the harsh winter conditions in the forest, which affects the sensors. While the measuring principle used to obtain the data is simple, the measurements are challenging and may not always be accurate, which must be taken into account in the use and analysis of the data collected. Although Melbourne Urban Forest and Hyytiälä present two very different types of forests, their associated datasets share the common issue of messiness at least in terms of accuracy and accessibility ().

Figure 6. Entry point for the Hyytiälä SMEAR II Patch, showing information about the selected Creature and options for viewing or adding Stories the tree may carry.

This could lead to diverse considerations and questions about what openness and accuracy of data might mean for different publics in speculating and, particularly, in making decisions that might affect many different lives in and around those forests. This insight guided the forming of some of the questions in the ‘Offer a Creature’ form on the Feral Map (). It asks participants to describe the age of the Creature they are adding, but also the time when they have sensed its presence in the place, both written from the participant’s own perspective. Further, in our acknowledgement of the history of the place – Melbourne – where the MtH Dérive and the Feral Map were first developed, we made a design decision that the meta-data capturing the time of creation of each Creature and Story will be shown in the season defined by the calendar of the Kulin Nation (consisting of the Boon wurrung, Woi wurrung, Taung wurrung, Ngurai-illum wurrung and Wutha wurrung peoples) who are the traditional owners of the land encompassing Melbourne and surroundings.

In the context of the OF project, the Feral Map carries experiences from different forest walks and movements of various walkers. Each walk is different, depending on who the walker and the guide are, the time of the day/year, and how the walk is arranged. So far, OF has organised walks in (what is known today as) Finland, Australia, the Czech Republic, Colombia, and the United Kingdom. The walks have been guided by scientists, indigenous weavers, forest healers, local inhabitants, and by a dog (Dolejšová et al., Citation2023). Because of this diversity of the walks’ locations and guides, we wanted to identify and gather these different experiences in some meaningful way in the OF project. We thus decided to add the ‘Patches’ layer to show the locations of these walks so that participants can situate their Stories and Creatures in the specific locations where their walks took place. Patches can be created (at this point, this is possible only by us the authors) for a specific geographical location (within an approximate radius around a latitude and longitude) to which a short description is added. Having Patches helps to differentiate the walks and provide more context for both the participants of the walks and visitors of the Feral Map. As we continued with our OF walks, we came to learn that some participants also wish to share their Stories about the entire Patch but had no means to do so on the map, which resulted in us adding a function that allows it.

Another messy and winded development of the map concerns the street names and other common geographical naming references. We initially removed these as a feral and anti-colonial action, but later reintegrated them when more and more people expressed that they wanted and needed these details to be able to meaningfully engage with the Feral Map. An illustrative case is that during one of the exhibitions of OF, an adult visitor browsing through the stories in Feral Map wanted to map a special tree of their childhood and offer a story (a memory) to it. However, finding the exact location became too challenging for them without the naming references visible on the map, and resulted in them walking away without adding the tree, lamenting. Building on our learnings from these kinds of messiness, we started to connect with other projects, this time with an intention to actively invite and experiment with differences arising in coalescing multiple creative inquiries. We will discuss this in more detail in the following section.

Entangled

As the map became populated with more data, we were able to experiment with new possibilities to entangle with other projects that had been developing separately. Doing so required considerations for and working with different entanglements between and among projects. In this section, we introduce two related projects to illustrate some of these entanglements.

Open Urban Forest

Open Urban Forest (https://creatures-eu.org/productions/open-urban-forest/) is an artistic research process exploring how human and other-than-human dwellers live with and around each other in the context of everyday, situated cohabitation. The exploration takes place in the specific context of a feral, nature-reclaimed communal site – ‘a forest-turned garden-turned forest’ – located on the steep hills of the Svratka river valley in the city of Brno, Czech Republic, where the project initiator Michal Mitro has been dwelling for the past eight years.

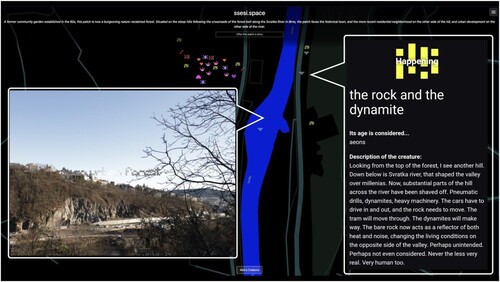

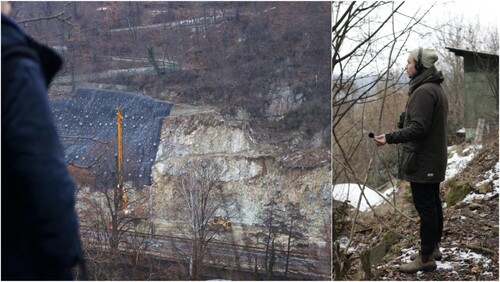

The site was established in the 1960s during the authoritarian Communist era in the socialist Czechoslovakia and served as a community garden, offering a space for the cultivation of crops and community engagement, providing a sense of ‘free’ space-time outside of the oppressive regime. This spirit of the site as a place for the cultivation of new life, resilience, hope and speculations on better futures has been preserved till today. The garden is still affected by various power struggles involving negotiations among local municipality authorities and (more-than-)human inhabitants: recently, the site has been affected by local urban planning that includes the building of a large road tunnel on the opposite side of the Svratka valley. The construction has impacted the lives of locals, for instance through clear-cutting of trees and removal of vegetation, and the noise produced by the construction – as also reflected in the local Feral Map patch (). As with the past, the forest-garden with a lush, free-roaming multispecies ecosystem still stands ‘in opposition’ to the municipality’s efforts in fostering a controlled and efficient flow of life in the city.

Figure 7. The Rock and the Dynamite Creature carrying Stories about the road tunnel construction and its impacts on the local landscape.

At the top of the steep forest-garden sits a small cottage also known as ssesi.spaceFootnote1 that functions as Mitro’s occasional home and an experimental ‘wood cube’ art gallery offering an alternative to the white cube standard (). Open Urban Forest (OUF) is one of the latest artistic research projects based and unfolding at the ssesi.space (details in Mitro, Citation2023).

Figure 8. sessi.space cottage on the top of the sloped forest-garden; a view through the garden’s canopy showing glimpses of the construction site.

OUF consists of a series of performative interactions involving various local experts who have been invited to observe the multispecies garden and its entanglements with the surrounding cityscape: who grows where and whose interests matter to whom. Local expert teams – for instance from forestry sciences, architecture, sound and performance art – use their distinct knowledge, tools, and skills to elaborate on diverse aspects of the site. Their collected materials – images, notes, videos, sounds, sketches and other sensorial impressions – were added to the Feral MapFootnote2 in the late 2022 after a year-long collaborative entanglement of the OUF and OF projects and their activities. The ssesi.space Patch expanded the map’s layers with new data and also new ‘layers’ of meaning to the map’s use. The Creatures and Stories added in the Patch by the project author and contributors often capture their observations and reflections emerging from the creative-critical processes undertaken within the OUF research, thereby turning the map into a research documentation tool and a form of a self-reflective diary.

Among the diverse ssesi.space Patch datapoints are snapshots from OUF expert interviews and conversations (e.g. a Creature titled How to Maintain the ForestFootnote3), performative events (e.g. Crisis and ProgressFootnote4), diurnal and nocturnal observations (e.g. Autumn FiestFootnote5), and various artefacts encountered throughout the project (e.g. Marten’s PresenceFootnote6). These map contributions of varied shapes and formats carry diverse perspectives on the possibilities of (local) more-than-human cohabitation that are made visible and available in the ssessi.space Patch for further reflection by all visitors of the Feral Map.

For instance, the OUF expert contributors from the AVA Collective – sonic enthusiasts re-searching environmental sounds – worked on the site to record local sonic footprints including a variety of ambient sounds such as unused gardening utensils, snails crawling in grass, or water interacting with metal objects. They also jammed with the heavy machinery operating at the road tunnel construction at the opposite side of the valley, aiming to capture the entanglements and clashes of local nature and human culture – as shown in the Recording the Pulse Story (see ).

Figure 9. Images from the Story Recording the Pulse showing AVA Collective’s jam with the beat of the tunnel construction. The accompanying description says ‘Daily 7 am till 7 pm. Piercing the earth. Making way for more traffic to pass through the valley.’

On the map, the documentation of AVA’s creative research activities on-site is further enriched by Mitro’s own reflection on the Collective’s engagements. For instance, The Invisible Presence of the Machine CreatureFootnote7 captures their conversation about the construction causing radically different visual and sonic footprints of the OUF garden, noting that the garden’s soundscape is composed mostly of ‘man-made and technological noises. Traf[f]ic, con[s]truction, ambulance sirens, even dynamite’ which is contrasting to how the wild, green, ‘roma[n]tic, slightly decadent’ forest-garden looks.

These ssessi.space datapoints offer a peculiar view on the current local environmental and socio-political situation, showing the road tunnel construction and its impacts on the local ecosystem from more-than-human, multi-sensory perspectives. The construction has been criticised heavily and opposed by local citizens, pointing out the harm it causes to the local life. The Feral Map as an open platform can function as an alternative information channel providing nuanced insights from lived experience of the damage caused by the development. Continuing its function as a place of ambient dissent in the 60s, the forest-garden, extended by the Feral Map, provides an occasion for a citizen-driven cultivation of diverse critical, personally situated reflections on the local eco-social developments.

Further, the Feral Map has also served as a creative medium for research documentation and reflection for the OUF participants. The very process of adding research notes – such as those discussed above – to the map as Creatures and Stories has created an opportunity for self-reflexive development of the OUF project. Some of these data entries capture authors’ unfolding thoughts, murmurations, and questions that other viewers might engage with and respond to. These new aspects and uses of the Map emerged along with its entanglement with the OUF project and the creation of the ssessi.space Patch, guiding both the Feral Map and OUF to change in unexpected directions.

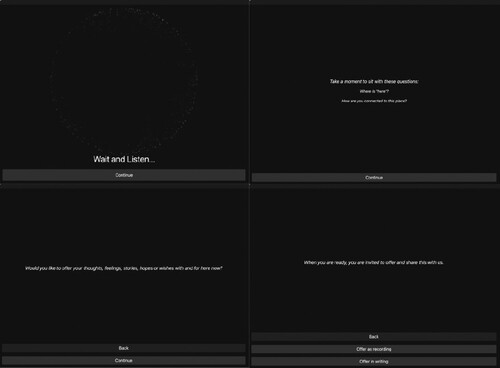

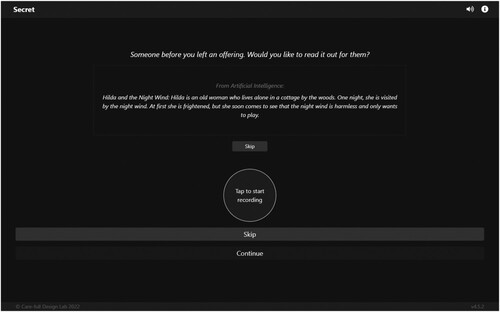

Secret Project

Secret Project (https://secret.more-than-human-derive.net/) is a digital participatory artwork which explores, through ritualistic, sound-based, and embodied interaction, different connections and entanglements with more-than-human worlds. It invites participants to meditate on, feel, and share their connection with the surroundings through sound (). Participants can offer audio recordings or written texts to be integrated recursively and in real-time into an evolving more-than-human soundscape, which brings together the audio recordings made from others in the local area – including human voices, quotidian sounds such as the sounds of local trams or birds – and ambient sounds related to the area such as the sound of the rain, generated algorithmically, integrating other parameters defined by data relevant to the area – for example, seasonal temperatures.

In this way, the participants’ contributions become part of a growing digital body of collective more-than-human voices from and as different places around the world. The work can be experienced online or in an immersive installation environment and encourages participants to question and sense-make being in and with place in different ways, especially through sensory modalities. Integrating the Feral Map further diversified the Stories: the Secret Project randomly displays texts selected from the pool of Stories that the original contributor opted to share for this purpose. The participant can then read it aloud, effectively turning the Story into a collective voice offered to the shared liminal space co-created by the two projects.

The entanglement of the Feral Map and Secret Project was in part made possible by the inherent messiness of the Feral Map dataset which are stored in a NoSQL database, which allows for data relations to be made in a non-tabular manner not requiring data to conform to a schema or strict preconfigured format conventionally used in managing relational data while offering interoperability with them. As such, the connection between the projects could be established without needing arduous database redesign or similar changes from either project. Learning from this experience, we created an outward-facing API (Application Programming Interface) for the Feral Map in 2022, allowing for a more accessible means for entanglements with other projects in the future.

This emphasis on inter-connections through story-sharing is further expanded and complicated by the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI), which is configured to algorithmically generate a written text with similar qualities to the existing Stories on the Feral Map. These AI-Stories are offered in the same way as human-created Stories to the Secret Project participant to read aloud (). The project’s entanglement with the Feral Map created additional exploratory space to question the meaning of digital data and its role in shaping the present and future of a place. We are currently exploring ways to map sound recordings from the Secret Project on the Feral Map, which would amplify the data-reciprocity between them.

The entanglements among the Feral Map and external projects such as OUF and Secret Project can be mutually beneficial: the map can expand the creative-critical space of these projects by offering additional channel for engaging and experimenting with different perspectives and practices; in turn, these interactions help to keep the map constantly evolving and expanding its creative uses, functions, meanings, and data.

Shapeshifting

At times we are asked to define what the Feral Map is. Each time requires us to question it ourselves rather than referring to the first or the last definition we might have used. The map is many different things and, at the same time, no-thing: it exists entirely in relations, manifesting diverse meanings, qualities, functions, and purposes depending on the relations we choose to focus on. In Open Forest, the map gathers co-created more-than-human forest data offered by diverse forest walkers. In Open Urban Forest, it holds space for creative cultivation of dialogic and reflexive actions for local change. In Secret Project, it (re-)mixes different forms of data generated for disparate purposes into a collective voice expressed in vibration. These possibilities were not defined at the outset of any of the projects involved but emerged during the course of their entanglements with the Feral Map. Beyond the general structure of the map’s layers, there was no predefined mode of its use and the contributors have, over the time, found their own ways of Feral Mapping: some focused mostly on adding Stories to the existing datapoints, and others prioritised adding a diversity of new Creatures.

As such, we hesitate to disentangle what the Feral Map has become and what exactly makes it feral, but we share below its three inter-related qualities that have surfaced to date and that illustrate how the map has emerged as a feral, shapeshifting project intended to challenge the dominant extractive, technocentric framing of particular algorithmic futures:

Openness to ambiguity and indeterminacy, inviting curiosity and direct engagement with the map: The Feral Map offers views of particular places that include datapoints of diverse – creative, poetic, and often decidedly ambiguous – forms and shapes. This is evident, for instance, in the Creature types that can be added to the map and that involve a varying level of ambivalence: from Animals and Plants to Glitches and Happenings, the map contributors are invited to add these datapoints while drawing on their personal understanding of what a ‘Glitch’ or a ‘Happening’ might be in the particular place. Furthermore, the Creatures have a varying visibility on the map at a given time: only those sensed at the moment of viewing the map are shown in full opacity, while the others appear semi-transparent. When exploring the map, participants would also quickly notice that many more Creatures become visible upon zooming in. The map reveals more varied, and at times surprising, facets of the place the more one engages with it.

Some of the map’s features – such as the Whispers that are randomly distributed within ±0.5° latitude and ±1° longitude of the Global City selected by the sender – are left deliberately opaque, without any explanation; inviting participants to be curious, explore, and arrive at their own interpretations of these features. The Feral Map thus aims to avoid being prescriptive and didactic and allow participants to map a place imaginatively, while drawing on their personal and situated perspectives and experiences. These ambiguities – and their indeterminacy – that are differently and differentially presented on the Feral Map are there to propitiate what de la Cadena (Citation2014) describes as ‘ontological openings … to conceptualize otherwise, in partial connection with difference’ requiring direct engagement.

Changing and becoming together based on specificities of difference rather than sameness: The Feral Map is always becoming and exists through its evolving relations to other, similar projects. These relations help to reveal continuities and fissures, rather than universal definitions or common language for efficient communication between the entangled projects. The Feral Map itself is made of various languages and includes, for instance, Stories of a Colombian Plant, a Finnish Sensor, a Czech dog, a Happening documented in English, and many more. The majority of the Stories and Creatures are still written in English – many of these would be deemed imperfect, containing typos and grammatical errors, which defies the concept of a universal language. Translation here serves as a means of commoning, or becoming together, and points to the (evolving) differences rather than the sameness as the basis of relating. Here, de Castro and Wagner’s (Citation2015) notion of translation resonates, in which it ‘becomes an operation of differentiation – a production of difference – that connects the two discourses to the precise extent to which they are not saying the same things, insofar as they point to discordant exteriorities between the equivocal homonyms between them’ (p. 73).

Prioritising relating rather than binary contestation: The Feral Map brings together diverse features whose functions and modes of use do not focus on increasing efficiency. Data on the Feral Map is messy and ‘dirty’ in the way Steyerl (Citation2016) describes it: ‘messed up and worthless sets of information’ and ‘a cache of surreptitious refusal … to be counted and measured.’ The Feral Map data structures are open to bugs and glitches, hence being potentially more difficult to maintain than what may be considered as clean, efficient data structures. The map refuses to be framed as ‘the other’ or the holder of ‘the other’ data. Instead, it exists contiguously to disarrange the very binary distinction by constantly negotiating a position within the existing technological ecologies. For instance, as discussed earlier, Mapbox’s limitations have not deterred us from using the platform: it provides us with accessible tools affordable within our currently available skills and resources. Furthermore, we have found that identifying and seeking ways to technically and conceptually address such limitations lends to ‘situated, knowledgeable, specific conversations about the coding and objectification of the world, and about the power-laden particularities of this coding’ (Schuurman & Pratt, Citation2002, p. 297), a critical aspect of transforming knowledge and worlds.

The above three qualities of the Fera Map – inviting ambiguity through direct engagement; changing and becoming together through difference; prioritising relating rather than binary contestation – have helped us to remain open to new transformative possibilities and question taken-for-granted ideas about places and their becomings. It also provides a space to generatively question mapping as a practice and a method. As well as our own artistic and research practices, which prioritise the act of relating through storytelling.

Conclusions

Telling, sharing, listening to, and creating feral stories demand a will for wonder, acknowledging diverse lived experiences, and engaging with all sorts of people, places, narrative devices, theoretical queries, and plots despite the discomfort they might bring. The Feral Map gathers and carries stories but does not prescribe how they should be told or listened to. Similarly, we understand that our creative-critical approaches to provoking feral practices garner more questions than answers. Acknowledging the limitations of the Feral Map and our own creative practice, our current experimentations attend to the many possibilities and perils of mediating; applying various participatory design approaches based on more-than-human, embodied, and care-full co-creation (Choi et al., Citation2023; Dolejšová et al., Citation2023). By doing so, we hope to create relational places of engagement where we can ‘detect the traces of not-yet-articulated common agendas’ (Tsing, Citation2015, p. 254) for ‘creating-narrating-listening-hearing-reading-and-sometimes-unhearing’ (McKittrick Citation2021, p. 6). We invite you to join us in this humble, feral drifting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jaz Hee-jeong Choi

Jaz Hee-jeong Choi is an associate professor in Civic Interaction Design at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. Their transdisciplinary research and practice situate ‘care' at the core of transformational encounters and explore how radical transformation can materialise care-fully through creative-critical engagements. Jaz’s work is often experimental, multisensory, playful, and participatory work that starts from the margins. Currently, they are exploring the dynamics of creative practice as feral care, focusing on (1) its potential to arouse societal transformation in different cultural and more-than-human contexts, and (2) experimental and co-creative ways to form relational spaces to make sense of indeterminacy, plurality, and entanglements towards change.

Andrea Botero

Andrea Botero is an associate professor at the School of Arts, Design and Architecture of Aalto University (FI), and an adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Design at Universidad de Los Andes (COL). Her work engages with the possibilities and contradictions of participating in design and designing participation today. She is interested in what counts as design, what other practices for world-making are there, and which ones we need to call into being. Her research aims to understand how collectives (broadly speaking) come to understand the design spaces available to them and how designers could infrastructure those spaces better.

Markéta Dolejšová

Markéta Dolejšová is a design researcher and curator experimenting with feral, relational ways of knowing and doing, often in multispecies settings. She is currently affiliated as a postdoctoral research fellow at Aalto University – School of Arts, Design and Architecture (FI) where she helps to sprout a practice-based inquiry into more-than-human epistemologies and data (Open Forest) and teaches experimental design research. Previously, she worked with the CreaTures – Creative Practices for Transformational Futures EU project (2020–2022) where she led the Laboratory of Experimental Artistic Productions. Markéta has co-founded several art-design research initiatives including the Uroboros festival, the Open Forest Collective, the Feeding Food Futures network, and the Fermentation GutHub.

Lachlan Sleight

Lachlan Sleight is a creative technologist, designer, artist, and programmer who explores different kinds of human experience and our connection to nature - and ourselves. He works across a range of disciplines, including the extended reality (XR) spectrum, web, integrated electronics, sound design and interactive installations. His work has been shown in a variety of film festivals and exhibitions, including the Melbourne International Film Festival, Cannes, Venice, SXSW, and the Museum of Other Realities.

Notes

1 sessi.space Creature lives in the Feral Map at: https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/creature/-NHRbQvS7zQ10ndB3wEu.

2 The ssessi.space Patch exists at: http://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/?loc=ssesiSpace.

3 The Creature can be viewed at: https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/creature/-NII1UEmYjewRGJF4nYc.

4 The Creature can be viewed at: https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/creature/-NIb5LRHoVBWOhndDYxs.

5 The Creature can be viewed at: https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/creature/-NHLxS0NqYmkgqJkKEYW.

6 The Creature can be viewed at: https://feral.more-than-human-derive.net/creature/-NHLs6S9-XZPTuaF9492.

References

- Bell, G. (2010). CHI 2010 opening plenary: Genevieve bell – Messy futures: Culture, technology and research. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-a2gj2clzTk.

- Botero, A., Dolejšová, M., Choi, J. H.-J., & Ampatzidou, C. (2022). Open forest: Walking with forests, stories, data, and other creatures. Interactions, 29(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/3501766

- Caquard, S., & Cartwright, W. (2014). Narrative cartography: From mapping stories to the narrative of maps and mapping. The Cartographic Journal, 51(2), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1179/0008704114Z.000000000130

- Choi, J. H., & Botero, A. (2021). What does it mean to do things together?: Design’s conflicting relationships with democracy. Interactions, 28(6), 28–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/3489440

- Choi, J. H. J., Braybrooke, K., & Forlano, L. (2023). Care-full co-curation: Critical urban placemaking for more-than-human futures. City, 27(1-2), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2149945

- Cosgrove, D. (2005). Maps, mapping, modernity: Art and cartography in the twentieth century. Imago Mundi, 57(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308569042000289824

- de Castro, E. B. V., & Wagner, R. (2015). The relative native: Essays on indigenous conceptual worlds. Hau Books/University of Chicago Press.

- de la Cadena, M. (2014, January 13). The politics of modern politics meets ethnographies of excess through ontological openings. Theorizing the contemporary. Fieldsights. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-politics-of-modern-politics-meets-ethnographies-of-excess-through-ontological-openings

- Debord, G. (1958, June). “Definitions”. Internationale Situationniste. Paris (1) Translated by Ken Knabb. https://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/definitions.html.

- Dolejšová, M., Botero, A., & Choi, J. H. (2023). Open forest: Walking-with feral stories, creatures, data. Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work: The International Venue on Practice-centered Computing on the Design of Cooperation Technologies – Exploratory Papers, Reports of the European Society for Socially Embedded Technologies (ISSN 2510-2591). https://doi.org/10.48340/ecscw2023_ep11

- Elwood, S. A. (2001). GIS and collaborative urban governance: Understanding their implications for community action and power. Urban Geography, 22(8), 737–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2001.11501633

- Escobar, A. (2007). Worlds and knowledges otherwise. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 179–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162506

- Goffe, T. L. (2020). Unmapping the Caribbean: Toward a digital praxis of archipelagic sounding. archipelagos, (5). https://doi.org/10.7916/archipelagos-72th-0z19

- Greenfield, A. (2010, April 15). Ultramapping. http://speedbird.wordpress.com/2010/04/15/ultramapping/

- Griffin, A., & McQuoid, J. (2012). At the intersection of maps and emotion: The challenge of spatially representing experience. Kartographische Nachrichten, 62(6), 291–299.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Kearney, A. T. (2022). Readiness for the storm the 2022 global cities report.

- Keith, M., & Pile, S. (Eds.). (1993). Place and the politics of identity (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203016695

- Knight, L. (2021). Inefficient mapping: A protocol for attuning to phenomena. Punctum Books.

- Latour, B. (1993). The pasteurization of France. Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. (2016). Foreword: The scientific fables of an empirical La Fontaine. In V. Despret (Ed.), What would animals say if we asked the right questions? (pp. vii–xiv). University of Minnesota Press.

- McKittrick, K. (2021). Dear science and other stories. Duke Univesrity Press.

- Mitro, M. (2023). Open urban forest. In M. Dolejšová (Ed.), Creatures co-laboratory catalogue (pp. 88–95). CreaTures. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7525506

- Rancière, J. (2009). Afterword/method of equality: An answer to some questions. In G. Rockhill & P. Watts (Eds.), Jacques Rancière: History, politics, aesthetics (pp. 273–289). Duke University Press.

- Sassen, S. (2005). The global city: Introducing a concept. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 11(2), 27–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24590544

- Schuurman, N. (2000). Trouble in the heartland: GIS and its critics in the 1990s. Progress in Human Geography, 24(4), 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200100189111

- Schuurman, N., & Pratt, G. (2002). Care of the subject: Feminism and critiques of GIS. Gender, Place & Culture, 9(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369022000003905

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Steyerl, H. (2016). A sea of data: Apophenia and pattern (mis-)recognition. E-Flux Journal, (72). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/.

- Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

- Tsing, A. L., Mathews, A. S., & Bubandt, N. (2019). Patchy anthropocene: Landscape structure, multispecies history, and the retooling of anthropology: An introduction to supplement 20. Current Anthropology, 60(S20), S186–S197. https://doi.org/10.1086/703391

- Yeah Yeah Yeahs. (2003). Maps [Song]. On Fever to Tell. Interscope Records.