?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The EU has been on track toward growing disunity along geographical and political lines, expressed in growing anti-EU sentiments and the rise of Euroskeptic forces. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have functioned as a source of unity – revitalizing the European project by creating alliances in response to an external threat. However, as the war drags on, it begs the question of how brittle its new-found unity may be. This study thus seeks to examine the extent to which the war has mended the geographical and political divisions in the EU. Focusing on elite cohesion, we analyse social media interaction to provide a relational view of the alliances of the members of the European Parliament. We find that parliamentarians did not become more cohesive: East-Western division remains pronounced, and Euroskeptic political groups became further isolated. These findings imply that Euroskeptic groups will likely continue to be a source of contestation inside of the European Union.

Introduction

Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 seemed to transform Europe within a matter of weeks, with the European project suddenly appearing more confident in itself than at any other time in recent history. Early studies showed growing public support for European integration – even in countries with the most unfavourable views of the EU, such as Poland and Hungary (Kriesi, Moise, and Oana Citation2022). Divisions around core issues appeared suddenly mended, as the war has brought new unity around refugees, defense, and energy policies. A continent fractured by previous crisis now came together to receive millions of refugees – with the historically most recalcitrant countries, such as Poland, taking the largest share. Meanwhile, investments in a united European defense have skyrocketed, with historically neutral Sweden and Finland seeking to join NATO, and Germany pledging to substantially boost their military spending (Orenstein Citation2023).

This new-found apparent unity in response to the Russian invasion contrasts sharply with the divisions, conflicts and backlash that characterized the response to previous crises, such as the 2012 European Debt Crisis, the 2015 Refugee Crisis, or Covid-19. Through the past period of crises, EuroskepticFootnote1Footnote1 parties have emerged as a powerful political force in several European countries (Cramme and Hobolt Citation2014; Dijkstra, Poelman, and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020), simultaneously driven by (Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2016) and driving (de Vries and Edwards Citation2009) anti-EU sentiments among European voters. As these forces have grown in influence on both sides of the political spectrum, the European Parliament (EP) – as the singular European institution with directly elected members – has become a battleground, characterized by high levels of division and fragmentation (Halikiopoulou, Nanou, and Vasilopoulou Citation2012; McDonnell and Werner Citation2020). These divisions within the parliament are representative of backlash against the European Union (EU), that have at the same time undermining the EU’s capacity to act decisively and effectively when facing crises (Otjes and Van Der Veer Citation2016).

While the invasion of Ukraine appears to have been met by a resolute political response among the European states and a rejuvenated energy for the European project among the broader population (Schulte-Cloos and Dražanová Citation2023; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Citation2023), it remains uncertain whether this will translate to increased cohesion and cooperation within European institutions. Even the unified condemnation against the Russian aggression is not without cracks in the façade. Many of the Euroskeptic parties in Europe have long-standing ties with Moscow (Ivaldi and Zankina Citation2023), such as the radical right Northern League in Italy, and National Popular Rally in France (Makarychev and Terry Citation2020; Shekhovtsov Citation2017). Viktor Orbán – the main Russian ally in Europe – was re-elected with significant margins only weeks after the invasion. While some of the traditional Russian allies have condemned the invasion, adjusting their position to public opinion, the response is not homogenous but dependent on socioeconomic and historical factors (Carlotti Citation2023; Ivaldi and Zankina Citation2023).

This development may jeopardize the initial signs of reconciliation between Eastern and Western countries in the EU. Many Eastern European voters, previously sceptical of the EU, now find themselves more threatened by Russia’s territorial expansion and, consequently, are becoming more supportive of collective action. However, as the war prolongs, some political actors in Eastern European countries have started capitalizing on pro-Russian sentiments, emphasizing the people's interests in light of the rising energy costs resulting from the war (Zankina, Citation2023).

We thus inquire: to what extent did Russia’s invasion of Ukraine help mend the geographical and political divides among the European political elite? We address this question by focusing on relations among the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), as it is the only European representative body, it is at the core of politicization around European integration, and its co-legislative role in the EU (Bélanger and Schimmelfennig Citation2021; Braghiroli Citation2015; Wright and Guerrina Citation2020). The conflicts and allegiances of the parliament mirror the broader political struggles of the EU, making the EP the foremost arena in which the coherence and divisions of the EU are playing out. The unity of the EU is ultimately embodied and personified in the relations, networks, and interactions of the European political elite. In examining the divisions of the EP, we take a social network perspective, drawing on a long literature that examines the patterns of relations as both expressions of the broader political unity (e.g. van Vliet et al. Citation2023; van Vliet, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2021), and key to enabling political institutions to cooperate across competing fractions (e.g. Grossmann and Dominguez Citation2009; Koger, Masket, and Noel Citation2010; Schwartz Citation1990; Waugh et al. Citation2009). In the context of social network analysis, we focus on the notion of cohesion, referring to the extent to which a network is unified as a whole rather than split into competing or conflicting fractions (Newman Citation2018). The network cohesion has been found to be a central factor to overcoming collective action problems and reaching agreement on difficult issues (Gould Citation1993; Heaney and McClurg Citation2009).

To capture relationships between MEPs, we use the interactions between European parliamentarians on Twitter as data. Studies have shown that politicians employ the affordances of the platform to show proximity or distance from one another (cf. Calais Guerra et al. Citation2011; Conover et al. Citation2011; Metaxas et al. Citation2015), and that MEPs retweet networks can be powerfully employed to study the structure of divisions, alliances, and conflicts within a particular political system (Crossley et al. Citation2015; van Vliet et al. Citation2023; van Vliet, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2020; Citation2021; Weaver et al. Citation2018). We also study the content of their messages to identify the topic and focus of discussions over time. Drawing on these measures, we take a quasi-experimental approach, examining whether Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to shifts in the network cohesion of the EP.

Our findings show that while the war quickly became the central focal-point of discussions following the invasion, completely dominating the agenda for a period. However, it did not remain an all-encompassing focus of discussion for long, but was replaced by new issues. In particular, the political groups furthest left and right on the political spectrum were least prone to mentioning the war. We find deep geographical and political divisions among the political elites before the war, and that these were not significantly mended by Russia’s invasion. Our analyses furthermore show that Euroskeptic political groups became even more isolated from the Europhiles, suggesting that the war may have deepened divisions between pro- and anti-European forces within the parliament. These results suggest that the invasion did not increase cohesion within the EU, and that the centrifugal forces in the EP are likely to persist.

A watershed moment for the union

As Russia planned the invasion of Ukraine, the EU was still shaken from an unprecedented series of crises – including the 2012 European Debt Crisis, the 2015 Refugee Crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic. The European Union’s faulting responses to those crises left scars on the public trust in the Union’s capacity to meet common challenges. For many, early dreams of a common project for peace and prosperity had long since been replaced by the bleak reality of governing; the union became seen as slow-moving, bureaucratic, undemocratic, and lacking in consensus. These perceptions contributed to sparking a political backlash in the shape of growing Euroskeptic movements around the Union, seen in Brexit – the departure of the United Kingdom from the EU – and the rise to power of Euroskeptic parties around the European national states (Cramme and Hobolt Citation2014; Dijkstra, Poelman, and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020; Kriesi Citation2020). Euroskeptical parties from the left and right sides of the political spectrum have also become an established force (Halikiopoulou, Nanou, and Vasilopoulou Citation2012; McDonnell and Werner Citation2020). Although the results of the 2019 European election were disappointing for the European radical right, they have arisen as the fifth political force in the EP (Ripoll Servent Citation2019).

The war in Ukraine in many ways seems to have driven a sudden shift in this trend, fuelling an immediate surge in public support for European integration (Steiner et al. Citation2023; Schulte-Cloos and Dražanová Citation2023). Following the invasion, Ukrainian flags were hoisted on balconies and social media profiles around Europe, serving not only as a symbol of Ukrainian solidarity but also – somewhat unexpectedly – as an unofficial symbol for the European liberal project. This rise in public support for the Union can be explained by the war serving as a stark reminder for European citizens of the advantages of being part of the EU, in particular pertaining to issues such as defense and energy security (Gabel and Whitten Citation1997; Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016; Hooghe and Marks Citation2005). Another explanation is the role of identity, as a common external threat serves as an important source of identity building and cohesion inside Europe (Gaertner and Dovidio Citation2014; Myrick Citation2021; Stein Citation1976). Since its inception, the EU has struggled to construct a sense of common identity among its population: the proportion of the population who identify primarily as ‘European’ has grown only marginally during the last decades’ rising European political integration, reaching a highpoint of a meagre 3% (Negri, Nicoli, and Kuhn Citation2021). The war brought back old the memories of the Russian threat, defining an ‘other’ that boosted the sense of shared identity, as Russia’s violent disregard for the international order has presented the liberal European project in flattering contrast to its antithesis (Fukuyama Citation2022).

While studies have shown that the war has led to a shift in public opinion about the EU (Schulte-Cloos and Dražanová Citation2023; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Citation2023), the extent to which those transformations have also halted the anti-EU attitudes among the political elite and led them to cooperate on a common European future remains inconclusive. On the one hand, Russia military offensive in Ukraine to have animated powerful unity and cooperation among European member states, with unprecedented weapons shipments to Ukraine and equally unprecedented economic sanctions – perhaps better understood as a new form of ‘economic warfare’ (Mulder Citation2022). For the EU, previously divisive issues such as defense spending and the energy sustainability transition (Siddi Citation2016; Szulecki et al. Citation2016) now became points of unity, with countries such as Germany cancelling their controversial gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 and making large pledges for investment in defense spending.

The geographical divisions between the East and West of the Union similarly show some signs of mending, as some of the Eastern countries that were previously most sceptical toward the EU have found themselves most under threat by Russia’s pursuits of territorial expansion. These countries have also taken on most of the costs of the crisis – receiving a plurality of Ukrainian refugees and suffering most of the rising energy costs due to their dependence on Russian gas (Eurostat Citation2022). Poland, for instance, was previously at odds with the Union for its anti-migration position, but has now opened their doors to receiving millions of Ukrainian refugees, taking a strong stand toward Russia while seeking inclusion and cooperation with the Union (Krzyżanowski Citation2018).

On the other hand, other indicators suggest that Europe will remain geographically and politically divided, with deeply rooted anti-European sentiments within its political elite. Russia has strategically expanded its influence in Europe through cooperation with Euroskeptic parties on both the radical right and left (Krekó and Győri Citation2016; Makarychev and Terry Citation2020; Shekhovtsov Citation2017), aiming to legitimize Russia’s actions and challenge the Western liberal-democratic consensus (Shekhovtsov Citation2017). While Russia’s influence in Eastern Europe is long-standing (Enyedi Citation2020; Holesch and Zagórski Citation2023), Kremlin has actively expanded its connection with Euroskeptic parties also within the West after 2014 (Polyakova Citation2014). Whereas most Russian allies in Western Europe are either on the margins of the political spectrum or participating in the government with mainstream parties, they have entered well into the political mainstream in Eastern Europe (Kopecký and Mudde Citation2002; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2016). As the example of Vitor Orbán shows, these leaders have been recalcitrant to working with the EU in meeting common challenges (Krastev Citation2017; Krzyżanowski Citation2018; Maricut-Akbik Citation2021). The political relevance of the Russian ties to European parties thus cannot be dismissed, as research indicates that these groups tend to support pro-Russian interests in the EP (Braghiroli Citation2015; Krekó and Győri Citation2016). Although these ties might face challenges due to public support for Ukraine (Carlotti Citation2023), Euroskeptic pro-Russian political actors might still find ways to exploit war fatigue and the increasing cost of war, claiming to act in the name of the people's interests against the Brussels elite (Ivaldi and Zankina Citation2023). Also, the Russian ties to European parties may undermine the mending effects of the Russian invasion of political divisions between Eastern and Western Europe.

Thus, it is yet to be seen if the Russian invasion of Ukraine will indeed mend divisions within Europe, fostering elite cooperation around the European project, or whether the brittle new-found unity will break under the pressures of imposed economic and political costs, as the EU grapples with skyrocketing energy prices, inflation and a drawn-out war.

In this paper, we will contribute to this debate by examining the relational structure of the MEPs. The EP is the only European institution which members are directed elected, and is the institution that adopts directives in most policy fields, together with the Council of the EU (Kantola, Elomäki, and Ahrens Citation2022). We view the relational structure among parliamentarians as both mirroring the broader political divides and conflicts of the European Union institutions, and as part of itself shaping the capacity of the union to act politically and cooperate across competing fractions (e.g. Grossmann and Dominguez Citation2009; Koger, Masket, and Noel Citation2010; Schwartz Citation1990). We thus examine the network cohesion of the parliament as a relational lens into the divisions and contestation of the political elite of the Union (Braghiroli Citation2015; Wright and Guerrina Citation2020).

Cohesion of members of the European Parliament

There are several ways to define and operationalize the notion of cohesion within the parliament. One way in which such cohesion is studied is by looking at formal expressions – in particular voting behaviour, which reveals the extent to which members of a certain group vote in agreement and follow party leaders’ guidelines (Tsebelis Citation1995). A similar approach has been taken to examine voting cohesion within political groups within the EP (Faas Citation2003; Hix Citation2001; Hix, Noury, and Roland Citation2005) as well as within committees (Settembri and Neuhold Citation2009). This approach allows capturing the capacity of these institutions to foster internal consensus and influence policymaking. These studies have shown that MEPs largely vote in accordance with their party group, and that the parliament has historically had a remarkable capacity to promote consensus across political groups from the left and right sides of the political spectrum – at least on the issues that are brought up to vote (Settembri and Neuhold Citation2009).

However, the consensual modus operandi of the EP has been challenged in the last years by the increasing presence of Euroskeptics party groups adding a permanent dissonant voice to the chamber (Ripoll Servent and Panning Citation2021). Research has moreover shown that MEPs from Euroskeptics party groups often disengage from formal parliamentary work (Brack Citation2018), which has led scholars to turn to informal venues and intergroup dynamics to assess their impact on European democracy legitimacy and the political conflicts in the chamber (Kantola and Miller Citation2021; Ripoll Servent and Panning Citation2021). The resulting studies have revealed deeper divisions and polarization in the EP compared to the data on formal venues, with great isolation of Euroskeptics party groups.

While voting behaviour captures the ability of institutions to make their members fall in line around votes, it is less informative of the interpersonal and social ties among parliamentarians that have been shown to be key in enabling cooperation and political action (Gould Citation1993; Heaney and McClurg Citation2009). In this study, we examine the structure of allegiances among MEPs in the EP on the social media platform Twitter as a means of investigating the divisions and cohesion within the European political elite.

Twitter enables users to write brief messages that can be shared by others, and has become the go-to platform for politicians to engage in communication and interaction. Centrally, the platform also provides affordances to engage with one another in debate by ‘mentioning’ or share messages by ‘retweeting’. These actions are made publicly, and have become ways for politicians to enact and signal allegiances and disagreement in relation to both issue positions and other politicians (Esteve Del Valle et al. Citation2022; Van Vliet, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2021). While direct and quotidian, the interaction on Twitter is thus simultaneously partially performative: messages are sent in public, and when politicians are ostensibly interacting with one another, they are doing so in part to communicate to a broader audience (see e.g. Hänska and Bauchowitz Citation2019; Hemsley et al. Citation2018; Jungherr Citation2016); suggesting that interactions on Twitter thus exists at the intersection between a formal and informal setting. The pattern of retweets also captures cultural and political boundaries between parliamentarians. For instance, MEPs may choose to write in their national language – making it harder for their colleagues to engage with their messages, and less likely that they will retweet them (van Vliet et al. Citation2023). We argue that such practices are themselves significant for the relationship among parliamentarians, and that retweets thus captures multifaceted relationships among MEPs.

Previous research has shown that the structure of communication on Twitter can provide a powerful gaze into the structure of elite political allegiances and divisions (e.g. Crossley et al. Citation2015; van Vliet et al. Citation2023; van Vliet, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2020; Citation2021; Weaver et al. Citation2018), as politicians strategically make use of the affordances of social media to express their political positions vis-à-vis other actors. These data thus allow taking a relational approach to examining the divisions of the EU, viewed through the interpersonal relations of the political elite. By studying Twitter messages, we can thus get a view into the relational structure of political elites, which allows us to capture division and cohesion within the political body. We focus on the institution’s relational cohesion, which we – drawing on the literature on social network analysis – understand as the degree to which members within a social network are connected to a larger whole, as opposed to divided into isolated fractions (Newman Citation2018). As an extensive literature has argued, such cohesion is central to enabling institutions to collective action problems and reaching agreement on difficult issues (Gould Citation1993; Heaney and McClurg Citation2009).

Taking into consideration the theoretical discussion on the elite cohesion of MEPs, in examining the European parliamentary network, we expect:

H1a: MEPs from Euroskeptic political groups to be less attached to Europhiles MEPs than to other Euroskeptic MEPs.

H1b: MEPs from Eastern European countries to be less attached to Western European MEPs than to other Eastern European MEPs.

In comparing the EP network before and after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we develop competing expectations:

H2a: The invasion of Ukraine to lead to MEPs from Euroskeptic political groups becoming more attached to Europhile MEPs.

H2b: The invasion of Ukraine to lead to MEPs from Euroskeptic political groups becoming less attached to Europhile MEPs.

H2c: The invasion of Ukraine to lead to MEPs from Eastern countries becoming more attached to MEPs from Western Europe.

H2d: The invasion of Ukraine to lead to MEPs from Eastern countries becoming less attached to MEPs from Western Europe.

Methods and data

The official website of the European Union provides the Twitter handles for all MEPs together with information about their country and political group (European Parliament Citation2023). Drawing on this data, we used the Twitter Academic API to collect all tweets from all MEPs in the period from three months before to three months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24. This results in a dataset of 226,213 tweets, from 441 parliamentarians. As the parliament has 705 MEPs, we can conclude that the Twitter participation rate is relatively high. From these tweets, we extract retweets between parliamentarians, resulting in a dataset of 9,249 retweets. It is important to note that ‘quote retweets’ are not considered retweets by the Twitter API and are not included in our analysis.

We focus on retweets as a substantial body of research has shown that direct retweets are almost exclusively used to approve a given message, thus capturing support and endorsement among parliamentarians. We do not include comments or quote retweets, as these can be used either positively (e.g. encouraging or endorsing) or negatively (e.g. critiquing or ridiculing), which makes them less useful for capturing the structure of positive relationships (Keuchenius, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2021). In particular for politicians, studies show that retweets can be used as a proxy for endorsements, as politicians strategically employ the affordances of the platform to associate or disassociate themselves with others (Calais Guerra et al. Citation2011; Metaxas et al. Citation2015; Wong et al. Citation2016). The association between retweets and support is so strong that political positions can be predicted with high accuracy from retweet structures (Calais Guerra et al., Citation2011; Conover et al. Citation2011). Drawing on this, we follow existing research in using parliamentary retweet networks as a powerful relational perspective into the structure of elite alliances and conflicts within a particular political system (van Vliet et al. Citation2023; van Vliet, Törnberg, and Uitermark Citation2020, Citation2021).

We treat Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a form of natural experiment, examining how this event impacted the structure and cohesion of EU’s communication network. A natural experiment is an empirical study in which the effects of a particular event – outside the control of the investigators – are evaluated. With this aim, we divide the tweets by whether they were posted before or after February 24, to allow comparing the resulting networks. This provides an immediate perspective on how the war impacted the structures of allegiances within the EP. For more detailed temporal analysis, we also group all tweets by the week of their posting – setting February 24 as day 1 of week 0, with the included weeks spanning from −10 to +10.

We employ two methodological strategies for studying the resulting endorsement networks. First, we use Visual Network Analysis (VNA) – a qualitative form of network analysis that offers an open and flexible view of the network structure (Gamper, Schönhuth, and Kronenwett Citation2012). VNA is an established method based on employing an algorithm through which strongly connected nodes are situated closer together, and weakly connected nodes further apart (Decuypere Citation2019). We here employ the force-directed algorithm ForceAtlas2 (Jacomy et al. Citation2014) for generating the network visualization, which simulates a physical system of centripetal and centrifugal forces to spatialize the network. This allows us to use the visualizations as powerful and flexible ways to analyse the structure of relations. The networks were analysed in Gephi.

Second, for a more formal measurement of the level of cohesion between political groups and geographical regions, we make use of the so-called E–I index (Crossley et al. Citation2015; Domínguez and Hollstein Citation2014). The more that parliamentarians endorse across political or geographical lines, the more cohesive the network is. If parliamentarians primarily retweet within their geographical regions or political groups, this indicates that these lines of division run deep within the parliament. The E–I index is defined as follows:

(1)

(1) where E is the number of retweets that cross the group lines, and I is the number of retweets that are within the group. The E–I index is in the range [−1, 1], where −1 means extreme division – with only internal retweets and no retweets to external groups – and 1 implies that all the retweets are external. If the E–I index is 0, the parliamentarians are just as likely to retweet politicians from a different group. As the E–I index equals the sample proportion multiplied by two minus one,Footnote2 we calculate 95% confidence intervals by adapting the standard measures for the confidence interval of the mean.

Following Brack (Citation2018), we classify the political groups in the EP into Euroskeptic or Europhiles according to .

Table 1. Classification of political groups in the European Parliament.

Finally, as the analysis pertains to social media data, some ethical considerations must be made. Twitter is characterized by a high level of accessibility and publicness, without requirement for registrations to access, and users being aware that their comments are made publicly. Twitter can therefore be understood as a ‘public space’, for which individual consent is not required in line with the praxis in the field, and the guidelines provided by the British Sociological Association (BSA Citation2017) and the Association of Internet Researchers (Franzke et al. Citation2020). The data here is used furthermore pertain to public figures, which significantly reduces ethical issues regarding privacy. Nevertheless, as we consider the privacy and integrity of the users as essential, we here avoid linking statements or positions to specific individuals.

Results

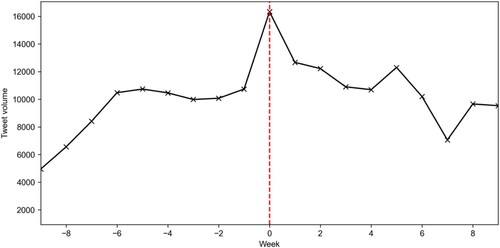

We begin by examining the number of tweets posted per week over the period (). This graph shows a substantial increase in the number of tweets sent by MEPs during the week of the invasion, with an increase from roughly 10,000–16,000 tweets compared to the preceding week. The event thus has a clear impact on the Twitter activity of the parliamentarians.

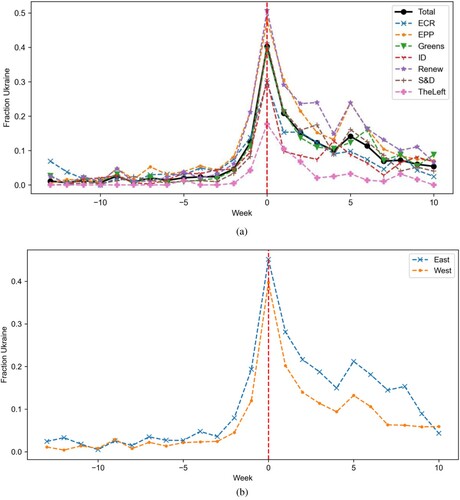

To examine the longevity of the event in the attention of the parliamentarians, we focus on what hashtags the parliamentarians use. shows the relative frequency of the most used hashtags per week. As can be seen, the war becomes the nearly all-encompassing focal point of attention immediately following the invasion. Relatively quickly, however, other issues crawl back into the agenda. To get a sense of the differential impact of the war on different political groups and countries, we manually classify all hashtags by whether they are linked to the Ukraine war and look at a fraction of hashtags used by each country and political group that pertains to the war. The list of hashtags in this study is available in the Supplementary Material. (a, b) shows the result, revealing a strong initial response to the war, which, however, fades relatively quickly. Among the political groups, The Left and ID are the least focused on the event – representing the more Euroskeptic positions on each side of the political spectrum, as well as the groups with some more pro-Russia members (Braghiroli Citation2023). In relation to the European geographical division, Eastern and Western countries reacted similarly to war, however, the attention to the event faded more quickly in the East than in the West.

Figure 2. Graph showing the distribution of the 50 most used hashtags each week, with their size proportional to their relative frequency of use. Hashtags pertaining to the war are shown with grey background and white text. The vertical red dotted line signifies the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 3. (a) These graphs show the proportion of hashtags that pertain to Ukraine over time, per political group and geographical division respectively. This includes all hashtags that have been classified as referring to the war. (b) The second graph compares the East and West European countries.

Effects of the war on European cohesion

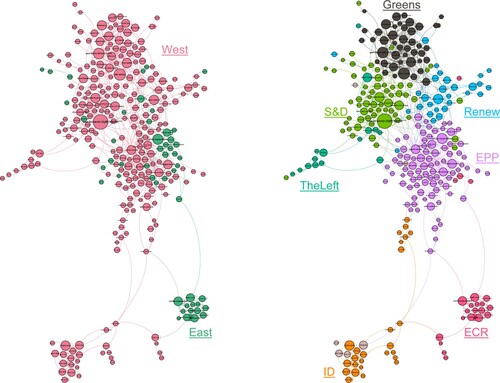

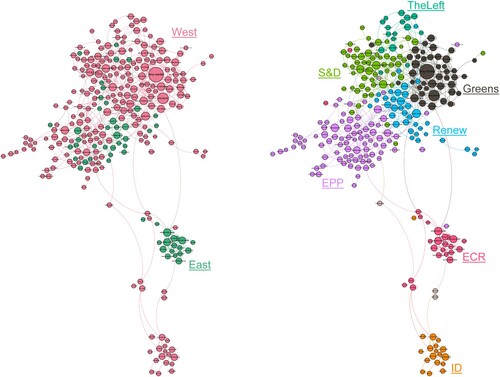

To examine the effects on the coherence of the MEPs, we begin by taking a Visual Network Analysis approach to the endorsement network before the invasion, providing a qualitative sense and an overview of the network’s structure. (a, b) shows the network prior to the invasion, with the left figure showing nodes coloured according to the geographical divide and the right figure according to the political group. This network shows the 278 nodes that are included in the network’s giant component, meaning that nodes or clusters that are not interconnected with the larger structure are not included. The giant component is the only major cluster in the network, as the excluded nodes are either not connected to any node or are connected to only one or two other nodes.

Figure 4. Retweet network before the war. Retweet structure of the parliamentary network. (a) The left figure shows the parliamentarians by whether they represent East or West Europe, while the right network shows the parliamentarians’ political group. (b) The network reveals the fractures and divisions of the union, in particular how the Eurosceptic political groups are split from the larger union. Geographically, Europe is relatively more integrated, except for a group of ECR’s parliamentarians (lower right) who are strongly split from the larger network.

As can be seen in (b), the divisions of the network correspond almost perfectly to the political groups. While all groups are clearly separated, the Greens, Social Democrats (S&D), Renew, and European People’s Party (EPP) are relatively more connected. A deeper division runs between these groups and the Left, European Conservatives & Reformists party (ECR) and ID – all of which are Euroskeptic political groups. We find that some MEPs from ID and ERC are connected to the mainstream cluster through MEPs from EPP. To the right of the mainstream cluster, with links to S&D, we find the political group The Left – some of whose members are however fully integrated with the mainstream cluster. Focusing on the relationship between the divisions and between East and West ((a)), we see that the larger cluster consists of members from both Eastern and Western Europe. The most isolated members of the ERC are from Eastern Europe ((a,b)).

We now turn to visually examining the network after the war, to see whether and how the structure of the network shifted as a result. (a, b) shows the resulting network after the Ukraine invasion, with the same node colours as (a, b) to allow visual comparison. Based on the figures, there does not appear to be a radical shift in the structure of the retweet network. The network remains highly fractured along the political group line ((b)), and Euroskeptic groups remain situated outside the main cluster. MEPs from the ID group appear even more isolated – now connected to the mainstream cluster only through a bridge formed by members of the ECP. Regarding the Eastern-Western division, (a) shows that the mainstream cluster continues to include MEPs from both East and West Europe, and the Eastern European MEPs for the ECR remain isolated. These results suggest the war did not have a transformational qualitative effect on the structure of endorsements.

Figure 5. (a, b) Endorsement networks after the war. This graph shows the retweet structure of the parliamentary network after the war. As can be seen, the network is not visibly more cohesive than before the war. The political groups that were outside of the main cluster remain so following the war.

However, while VNA gives a simple and intuitive overview of the network structure, with a qualitative impression of the communities and lines of division, it is limited when it comes to getting a precise estimate of the level of cohesion – in particular as each connection may represent one or several retweets. We thus turn to the quantitative E–I index for a more precise measurement of the level of cohesion along national and political lines.

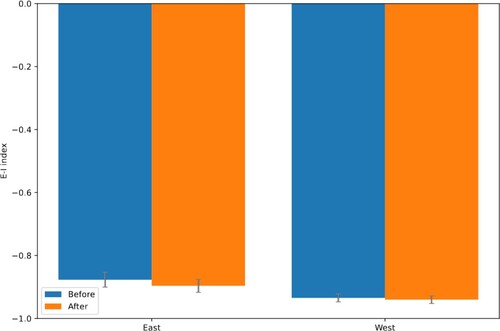

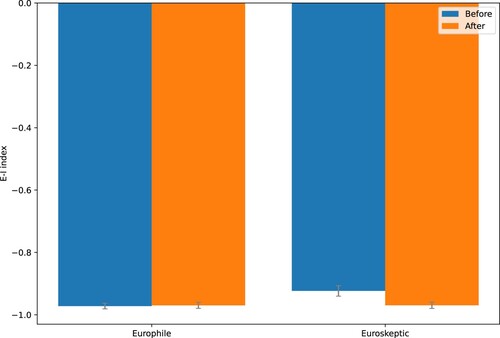

presents the resulting E–I index measurements for Europhile and Euroskeptic political groups before and after the war. It confirms the qualitative analysis showing that, before the war, MEPs from both Europhile and Euroskeptic political groups were highly isolated from each other, as evidenced by both E–I indexes being −0.972, and −0.923, respectively. This indicates that almost all endorsement occurred within the group, rather than across groups. We, therefore, accept H1a, which states that MEPs from Euroskeptic are more connected among themselves than to Europhiles MEPs.

Figure 6. E–I index, before and after. The figure shows that the network is fragmented among Europhile and Euroskeptic political groups. Particularly noteworthy is the increased isolation of Euroskeptic political groups following the war, with a 95% confidence level.

Examining the effects of the war, it appears that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to increased political fragmentation. This is illustrated by the inward shift within the Euroskeptic group, as indicated by the decrease in the E–I index measurement to −0.970, which is statistically significant with 95% confidence. This result leads us to reject Hypothesis H2a and accept Hypothesis H2b, which states that Euroskeptic political groups become further isolated after the war. In Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material, we repeat these analyses by political group. The results are consistent with those presented here and show that the ID group was the main driver of this outcome.

We can further focus specifically on the East–West divide in the EP. To quantify this divide, we examine the E–I index between MEPs from Eastern and Western European countries before and after the Ukraine invasion. shows a significant divide between Western and Eastern Europe prior to the war, with politicians from both East and West Europe being much more likely to endorse politicians from their own region rather than from across regions. This result supports Hypothesis H1b, which states that MEPs from Eastern European are more connected among themselves than to Western European MEPs. After the war, there was a slight inward turn, as illustrated by a decrease in the E–I indexes for MEPs from both Eastern and Western Europe. However, these results are not statistically significant within a 95% confidence interval. Therefore, we conclude that the war did not alter cohesion between the geographical regions, leading us to reject both Hypotheses H2c and H2d.

Conclusion

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has sparked renewed public enthusiasm for the European project, seemingly mending long-standing divisions within the union and a broken the political backlash against European integration in the public. But while research has found that the war has strengthened public support for the EU, its effect on the dynamics within the European political elite and the divisions and conflicts that have undermined the institutions capacity for political action is still inconclusive.

This paper seeks to contribute to our understanding of the effects of the war on European political elites, by examining how the invasion impacted relations among the members of the EP. The EP is the only directly elected institution in the EU, and has become a key stage for contestation over European integration, both expressing and accentuating the political and geographical divisions within Europe. We have focused on examining the level of network cohesion among MEPs, by comparing the structure of endorsements among MEPs in the EP on Twitter before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Twitter is an important arena for MEP interaction, and the structure of allegiance on Twitter offers a glimpse into the alliances and political divisions of the Union.

Our analysis showed that the attention to the war was intense but relatively brief, with new issues entering on the political agenda. We furthermore found that the structure of MEPs’ relations did not become more cohesive along either geographical or political lines. The invasion in Ukraine did not reduce the East–West division among MEPs, but in fact intensified the isolation of Euroskeptic political groups. These results complement previous findings based on MEP voting behaviour, showing that the Ukraine invasion did not weaken Eastern PRRPs alliances with Moscow (Holesch and Zagórski Citation2023). Nonetheless, further research is necessary to clarify the differences in response across Euroskeptic political groups.

These findings should not be taken as conclusive evidence that the European Union will not become more unified or cohesive in response to the Ukraine invasion, but rather that the existing relations among political elites have been recalcitrant to the rising public support for the EU. It is possible that meaningful shifts in the structure of elite relations in the EP may require time – and elections – to truly take hold. Future research may thus examine the longer-term effects of the Ukraine invasion on elite cohesion, as well as the effects of future elections. Future research may also focus on other European institutions; as the EP is the most politicized European institutions, where political and geographical division are more likely to manifest, analyses focusing on other European institutions, such as the European Commission, may find more cohesive elite relationships. It is also important to highlight that conclusions drawn from Twitter data are influenced by the frequency with which politicians use the platform. This usage might not be evenly distributed across political groups and regions, introducing potential bias in the analyses. Therefore, the analysis of parliamentarians’ cohesion in other formal and informal venues should complement the one presented in this study.

Our results suggest that Euroskeptic groups are likely to continue to be a source of contestation inside of the EU, and that they may over time seek to politicize EU’s responses to the invasion. While it may appear the EU has become more cohesive, with previously contested issues such as energy or refugee policy have now become areas of agreement, our findings suggest that interpersonal relationships remain deeply divided, and that the new-found unity may therefore neither be long-lived nor carry over to other issues.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this study, we understand Euroscepticism broadly, encompassing political groups that express conditional opposition to European integration, as well as groups that show unconditional opposition to it (Taggart Citation1998).

1 In this study, we understand Euroscepticism broadly, encompassing political groups that express conditional opposition to European integration, as well as groups that show unconditional opposition to it (Taggart Citation1998).

2 Proof: 2(a/(a + b)) − 1 = 2a/(a + b) − (a + b)/(a + b) = (2a − a − b)/(a + b) = (a − b)/(a + b).

References

- Bélanger, M. E., and F. Schimmelfennig. 2021. “Politicization and Rebordering in EU Enlargement: Membership Discourses in European Parliaments.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (3): 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881584

- Brack, N. 2018. Opposing Europe in the European Parliament: Rebels and Radicals in the Chamber. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Braghiroli, S. 2015. “Voting on Russia in the European Parliament: The Role of National and Party Group Affiliations.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23 (1): 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2014.978747

- Braghiroli, S. 2023. “Europe's Russia-Friendly Parties Put to the Test by Putin's Invasion of Ukraine.” Journal of Regional Security 18 (1): 29–38.

- British Sociological Association (BSA). 2017. Ethics Guidelines and Collated Re-sources for Digital Research. https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24309/bsa_statement_of_ethical_practice_annexe.pd

- Calais Guerra, P. H., A. Veloso, W. Meira, Jr, and V. Almeida. 2011. “Rom Bias Toopinion: A Transfer-Learning Approach to Real-Time Sentiment Analysis.” In Proceedings of the 17th ACMSIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD’11), 150–158. New York: ACM.

- Carlotti, B. 2023. “A Divorce of Convenience: Exploring Radical Right Populist Parties’ Position on Putin’s Russia Within the Context of the Ukrainian War. A Social Media Perspective.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 31 (4): 1–17.

- Conover, M., B. Gonc¸alves, J. Ratkiewicz, A. Flammini, and F. Menczer. 2011. “Predicting the Political Alignment of Twitter Users.” In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conferenceon Privacy, Security, Risk, and Trust, 192–199.

- Cramme, O., and S. B. Hobolt, eds. 2014. Democratic Politics in a European Union Under Stress. Oxford: OUP.

- Crossley, N., E. Bellotti, G. Edwards, M. G. Everett, J. Koskinen, and M. Tranmer. 2015. Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets: Social Network Analysis for Actor-Centred Networks. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Decuypere, M. 2019. “Researching Educational Apps: Ecologies, Technologies, Subjectivities and Learning Regimes.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (4): 414–429.

- de Vries, C. E., and E. E. Edwards. 2009. “Taking Europe to Its Extremes: Extremist Parties and Public Euroscepticism.” Party Politics 15 (1): 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808097889

- Dijkstra, L., H. Poelman, and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2020. “The Geography of EU Discontent.” Regional Studies 54 (6): 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- Domínguez, S., and B. Hollstein, eds. 2014. Mixed Methods Social Networks Research: Design and Applications (Vol. 36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Enyedi, Z. 2020. “Right-wing Authoritarian Innovations in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36 (3): 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787162

- Esteve Del Valle, M., M. Broersma, A. Ponsioen. 2022. “Political Interaction beyond Party Lines: Communication Ties and Party Polarization in Parliamentary Twitter Networks.” Social Science Computer Review 40 (3): 736–755.

- European Parliament. 2023. Members of the European Parliament. Accessed 28 August 2023. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/home.

- Eurostat. 2022. Energy imports dependency [Dataset]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/cbcde339.

- Faas, T. 2003. “To Defect or not to Defect? National, Institutional and Party Group Pressures on MEPs and Their Consequences for Party Group Cohesion in the European Parliament.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (6): 841–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00106

- Franzke, A. S., A. Bechmann, M. Zimmer, and C. Ess. 2020. “The Association of Internet Researchers.” Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.

- Fukuyama, F. 2022. Liberalism and Its Discontents. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gabel, M., and G. D. Whitten. 1997. “Economic Conditions, Economic Perceptions, and Public Support for European Integration.” Political Behavior 19 (1): 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024801923824.

- Gaertner, S. L., and J. F. Dovidio. 2014. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Gamper, M., M. Schönhuth, and M. Kronenwett. 2012. “Bringing Qualitative and Quantitative Data Together: Collecting Network Data with the Help of the Software Tool VennMaker.” In Social Networking and Community Behavior Modeling: Qualitative and Quantitative Measures, edited by M. Safar and K. Mahdi, 193–213. Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

- Gould, R. V. 1993. “Collective Action and Network Structure.” American Sociological Review 58 (2): 182–196. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095965.

- Grossmann, M., and C. B. Dominguez. 2009. “Party Coalitions and Interest Group Networks.” American Politics Research 37 (5): 767–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X08329464

- Halikiopoulou, D., K. Nanou, and S. Vasilopoulou. 2012. “The Paradox of Nationalism: The Common Denominator of Radical Right and Radical Left Euroscepticism.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (4): 504–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02050.x

- Hänska, M., and S. Bauchowitz. 2019. “Can Social Media Facilitate a European Public Sphere? Transnational Communication and the Europeanization of Twitter during the Eurozone Crisis.” Social Media Society 5 (3): 1–14.

- Heaney, M. T., and S. D. McClurg. 2009. “Social Networks and American Politics: Introduction to the Special Issue.” American Politics Research 37 (5): 727–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X09337771

- Hemsley, J., J. Jacobson, A. Gruzd, and P. Mai. 2018. “Social Media for Social Good or Evil: An Introduction.” Social Media + Society 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118786719

- Hix, S. 2001. “Legislative Behaviour and Party Competition in the European Parliament: An Application of NOMINATE to the EU.” Journal of Common Market Studies 39(4): 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00326

- Hix, S., A. Noury, and G. Roland. 2005. “Power to the Parties: Cohesion and Competition in the European Parliament, 1979–2001.” British Journal of Political Science 35 (2): 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123405000128

- Hobolt, S. B., and C. E. De Vries. 2016. “Public Support for European Integration.” Annual Review of Political Science 19 (1): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Holesch, A., and P. Zagórski. 2023. “Toxic Friend? The Impact of the Russian Invasion on Democratic Backsliding and PRR Cooperation in Europe.” West European Politics 46 (6): 1178–1204.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2005. “Calculation, Community and Cues: Public Opinion on European Integration.” European Union Politics 6 (4): 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116505057816

- Ivaldi, G., and E. Zankina. 2023. The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populist Studies.

- Jacomy, M., T. Venturini, S. Heymann, and M. Bastian. 2014. “ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software.” PLoS One 9 (6): e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

- Jungherr, A. 2016. “Twitter Use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Information Technology and Politics 13 (1): 72–91.

- Kantola, J., A. Elomäki, and P. Ahrens. 2022. “Introduction: European Parliament’s Political Groups in Turbulent Times.” In European Parliament’s Political Groups in Turbulent Times, edited by P. Ahrens, A. Elomäki, and J. Kantola, 1–23. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kantola, J., and C. Miller. 2021. “Party Politics and Radical Right Populism in the European Parliament: Analysing Political Groups as Democratic Actors.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (4): 782–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13181

- Keuchenius, A., P. Törnberg, and J. Uitermark. 2021. “Why It is Important to Consider Negative Ties When Studying Polarized Debates: A Signed Network Analysis of a Dutch Cultural Controversy on Twitter.” PLoS One 16 (8): e0256696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256696

- Koger, G., S. Masket, and H. Noel. 2010. “Cooperative Party Factions in American Politics.” American Politics Research 38(1): 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X09353509

- Kopecký, P., and C. Mudde. 2002. “The two Sides of Euroscepticism: Party Positions on European Integration in East Central Europe.” European Union Politics 3 (3): 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116502003003002

- Krastev, I. 2017. “The Refugee Crisis and the Return of the East-West Divide in Europe.” Slavic Review 76 (2): 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2017.77

- Krekó, P., and L. Győri. 2016. “Russia and the European far Left.” Institute for Statecraft. 5 April.

- Kriesi, H. 2020. “Backlash Politics Against European Integration.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (4): 692–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120947356

- Kriesi, H., A. Moise, and N. Oana. 2022. “The EU and Its Member States in the Ukraine Crisis: Some Public Opinion Results.” In Politics and European Identity Florence: Seminar Series Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2018. “Discursive Shifts in Ethno-Nationalist Politics: On Politicization and Mediatization of the “Refugee Crisis” in Poland.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 76–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1317897

- Makarychev, A., and G. S. Terry. 2020. “An Estranged ‘Marriage of Convenience’: Salvini, Putin, and the Intricacies of Italian-Russian Relations.” Contemporary Italian Politics 12 (1): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2019.1706926

- Maricut-Akbik, A. 2021. “Speaking on Europe’s Behalf: EU Discourses of Representation During the Refugee Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 43 (7): 781–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1855157

- McDonnell, D., and A. Werner. 2020. International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Metaxas, P., E. Mustafaraj, K. Wong, L. Zeng, M. O'keefe, and S. Finn. 2015. “What Do Retweets Indicate? Results from User Survey and Meta-Review of Research.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 9 (1): 658–661.

- Mulder, N. 2022. The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War. Yale: Yale University Press.

- Myrick, R. 2021. “Do External Threats Unite or Divide? Security Crises, Rivalries, and Polarization in American Foreign Policy.” International Organization 75 (4): 921–958. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000175

- Negri, F., F. Nicoli, and T. Kuhn. 2021. “Common Currency, Common Identity? The Impact of the Euro Introduction on European Identity.” European Union Politics 22 (1): 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520970286

- Newman, M. 2018. Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Orenstein, M. A.. 2023. “The European Union’s Transformation After Russia’s Attack on Ukraine.” Journal of European Integration 45 (3): 333–342.

- Otjes, S., and H. Van Der Veer. 2016. “The Eurozone Crisis and the European Parliament's Changing Lines of Conflict.” European Union Politics 17 (2): 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515622567

- Polyakova, A. 2014. “Strange Bedfellows: Putin and Europe's far Right.” World Affs 177: 36.

- Ripoll Servent, A. 2019. “The European Parliament After the 2019 Elections: Testing the Boundaries of the ‘Cordon Sanitaire’.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15 (4): 331–342. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1121

- Ripoll Servent, A., and L. Panning. 2021. “Engaging the Disengaged? Explaining the Participation of Eurosceptic MEPs in Trilogue Negotiations.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (1): 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1859596

- Rohrschneider, R., and S. Whitefield. 2016. “Responding to Growing European Union-Skepticism? The Stances of Political Parties Toward European Integration in Western and Eastern Europe Following the Financial Crisis.” European Union Politics 17 (1): 138–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515610641

- Schulte-Cloos, J., and L. Dražanová. 2023. “Shared Identity in Crisis: A Comparative Study of Support for the EU in the Face of the Russian Threat.” Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Working-Paper 2023/48.

- Schwartz, M. A. 1990. The Party Network: The Robust Organization of Illinois Republicans, 260. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Settembri, P., and C. Neuhold. 2009. “Achieving Consensus Through Committees: Does the European Parliament Manage?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (1): 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.01835.x

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2017. Russia and the Western far Right: Tango Noir. London: Routledge.

- Siddi, M. 2016. “The EU’s Energy Union: A Sustainable Path to Energy Security?” The International Spectator 51 (1): 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2016.1090827

- Stein, A. A. 1976. “Conflict and Cohesion: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 20 (1): 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200277602000106

- Steiner, N. D., R. Berlinschi, E. Farvaque, J. Fidrmuc, P. Harms, A. Mihailov, M. Neugart, and P. Stanek. 2023. “Rallying around the EU Flag: Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Attitudes toward European Integration.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 61 (2): 283–301.

- Szulecki, K., S. Fischer, A. T. Gullberg, and O. Sartor. 2016. “Shaping the ‘Energy Union': Between National Positions and Governance Innovation in EU Energy and Climate Policy.” Climate Policy 16 (5): 548–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1135100

- Taggart, P. 1998. “A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in Contemporary Western European Party Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 33 (3): 363–388.

- Truchlewski, Z., I. E. Oana, and A. D. Moise. 2023. “A Missing Link? Maintaining Support for the European Polity After the Russian Invasion of Ukraine.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (8): 1662–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2218419

- Tsebelis, G. 1995. “Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism and Multipartyism.” British Journal of Political Science 25 (3): 289–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400007225

- van Vliet, L., J. Chueri, P. Törnberg, and J. Uitermark. 2023. “Europeanization of the Political Arena on Twitter.” Party Politics.

- van Vliet, L., P. Törnberg, and J. Uitermark. 2020. “The Twitter Parliamentarian Database: Analyzing Twitter Politics Across 26 Countries.” PLoS One 15 (9): e0237073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237073

- Van Vliet, L., P. Törnberg, and J. Uitermark. 2021. “Political Systems and Political Networks: The Structure of Parliamentarians’ Retweet Networks in 19 Countries.” International Journal of Communication 15: 21. https://doi.org/10.46300/9107.2021.15.5

- Waugh, A. S., L. Pei, J. H. Fowler, P. J. Mucha, and M. A. Porter. 2009. “Party Polarization in Congress: A Social Networks Approach.” arXiv preprint arXiv:0907.3509, 3(4), 69.

- Weaver, I. S., H. Williams, I. Cioroianu, M. Williams, T. Coan, and S. Banducci. 2018. “Dynamic Social Media Affiliations among UK Politicians.” Social Networks 54: 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.01.008

- Wong, F. M. F., C. W. Tan, S. Sen, and M. Chiang. 2016. “Quantifying Political Leaning from Tweets, Retweets, and Retweeters.” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 28 (8): 2158–2172.

- Wright, K. A., and R. Guerrina. 2020. “Imagining the European Union: Gender and Digital Diplomacy in European External Relations.” Political Studies Review 18 (3): 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919893935

- Zankina, E. 2023. “Pro-Russia or Anti-Russia: Political Dilemmas and Dynamics in Bulgaria in the Context of the War in Ukraine.” In The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe, edited by G. Ivaldi and E. Zankina, 49–63. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies.