ABSTRACT

In recent years the ‘cost of governing’ has significantly increased for some mainstream political parties. In a context of financial uncertainty, multiple crises and growing constraints exerted by global forces, being a ‘natural’ party of government is no longer regarded as an electoral advantage. This is particularly true for parties that have moved from a position of clear dominance within ruling coalitions to a more subordinate role. In this article, focusing on the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and using an original dataset, we aim to provide a more nuanced assessment of the effects of incumbency by examining regional electoral performance since 1990. It appears that sub-national incumbency can be beneficial in regional elections, especially when a party faces significant costs of governing at the national level. However, this advantage is only applicable if the party holds a leading position in the regional executive. On the contrary, being a junior coalition partner at both national and regional levels may further exacerbate electoral decline for the party.

Introduction

Governing is the ultimate prize for most political parties but, particularly in recent years, it has also become an electoral liability in democratic systems. It is not rare to see parties entering triumphantly a new government and then ending their cabinet experience with a debacle at the ballot box. Literature has suggested that a ‘cost of governing’ exists in coalition governments of established democracies (Paldam Citation1986; Powell and Whitten Citation1993; Rose and Mackie Citation1983; Strøm Citation1990). This is particularly high for anti-establishment parties, which ‘lose the purity of their message by being seen to cooperate with the political establishment’ (van Spanje Citation2011, 609–610). While other, more qualitative studies have demonstrated that anti-establishment, populist parties can in fact thrive in government (Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2015), it has also been shown that some mainstream parties have been completely annihilated by their most recent governing experience – the French and Greek socialist parties being clear examples (Manwaring and Kennedy Citation2017).

However, although academic debates on the effect of incumbency have continued for decades, some questions have remained largely unresolved. In general, while it has been recognized that the cost of governing may differ between parties – mainly due to their varying ideological/programmatic characteristics – it is unclear whether the same party may be affected differently by incumbency depending on its role in the executive (as a leading or junior partner). Additionally, due to the ‘methodological nationalism’ that still characterizes most studies in comparative politics (Jeffery Citation2008), the cost of governing is mostly quantified by looking at the performance of national incumbents in general elections, leaving the impact of regional incumbency largely unexplored. Admittedly, some studies have examined ‘vertical linkages’ and ‘second-order’ effects on the performance of national incumbents in regional elections (Schakel Citation2015; Thorlakson Citation2020). Yet, again, little has been said on how different types of regional incumbency (or opposition) may moderate electoral effects of national incumbency. In sum, we need a more nuanced, ‘multi-level’ assessment of the cost of governing. This assessment should consider differences in the role a party can play in a governing coalition, going beyond the simple ‘government vs opposition’ dichotomy (horizontal dimension), and evaluate how national and regional incumbencies interact (vertical dimension).

This paper therefore aims to answer two interrelated questions: How do costs of incumbency change depending on what role a party plays in government? Does multi-level governance contribute to mitigate the costs of incumbency?

In order to address these questions, we need to analyse the case of a party that (1) has been in government multiple times playing different roles – i.e. as leading party AND junior partner (besides having spent some time in opposition) – and (2) has occupied these different positions at BOTH national and regional levels. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) is a rare example of party that fulfils both conditions and, therefore, allows us to test new hypotheses on the electoral impact of incumbency and draw some lessons that may be valid for other mainstream parties, whose electoral/representational dominance should no longer be taken for granted. Since the analysis focuses on one party in different regions of the same country, it will be possible to assess the impact of incumbency while holding other party-specific characteristics and state-wide socio-economic conditions constant.

We emphasize the fact that incumbency has varying effects on regional electoral performance depending on whether a party is a leading or junior coalition partner, as well as the territorial level of its incumbency. The conclusion underscores that leading a regional government can serve as a crucial political resource, particularly for a party facing the challenges of governing at the national level. Therefore, the SPD, which maintained its leading position in certain regional contexts despite experiencing periods of deep national crisis, can offer valuable lessons to other mainstream parties competing in multi-level systems.

This article makes significant contributions to advance research in the field of party politics and government in several ways. First, we establish a theoretical connection between literature on national and regional incumbency. This leads us to offer a more nuanced theoretical and empirical account of the ‘second-order election’ (SOE) model and its predictions concerning the punishment/reward of national incumbents in regional elections. Second, the findings of this article have the potential for generalization beyond the local study of the German case. Both the theoretical framework and the empirical analysis can be extended to other federal, quasi-federal and regionalized countries, such as Austria, Spain, or Italy, which have experienced an increase in political fragmentation and the emergence of diverse government coalition constellations at both regional and national levels. By demonstrating that different types of incumbency may have varying effects on the success of parties in distinct territorial arenas, we shed light on the complexities of multi-level political systems. Ultimately, this research contributes to the broader debate on the virtues and vices of multi-level governance within the context of transformations in the role of political parties and increasing challenges to democratic accountability (Katz and Mair Citation2018; Mair Citation2009).

The next section develops the theoretical framework of the article. We formulate two key hypotheses: a ‘horizontal’ one, which examines the impact of different government and opposition roles on regional electoral outcomes, and a ‘vertical’ one which instead considers the interactions between national and regional incumbency.Footnote1 We then move to the justification of the case selection and we set out the methodology of the article. We perform a quantitative analysis based on more than 100 Land elections in Germany. To facilitate this analysis, an original dataset has been created, encompassing a range of socio-economic and political variables, including new measures of party positions derived from a content analysis of regional manifestos.

Incumbency effects in multi-level systems

Extensive evidence presented in the literature supports the notion that controlling the national executive tends to be associated with a ‘cost of governing’. In an article on this topic, Joost van Spanje (Citation2011) provides an excellent overview of why this is the case. First, drawing from Downs (Citation1957), it is evident that even if a government represents a majority on various issues, it will end up alienating some minority of voters on each issue. Consequently, opposition parties may succeed in mobilizing a ‘coalition of minorities’, which will eventually erode and outnumber the government’s support. Moreover, Paldam and Skott (Citation1995) argue that even when centre-left and centre-right parties converge towards the centre on a unidimensional left-right continuum, they cannot become entirely identical and will continue to be influenced by the preferences of the electorate on their respective sides. Accordingly, centrist/swing voters may perceive government policy as too left-wing when a centre-left party is in power or too right-wing when a centre-right party is in power and a good portion of them will vote for the opposition party. Finally, voters tend to hold the government more accountable when the economy faces a downturn and are less likely to reward it when it is thriving: this phenomenon is also called ‘grievance asymmetry’ (Bloom and Price Citation1975; Mueller Citation1970).

van Spanje (Citation2011) expanded on these theories but took a different perspective, suggesting that the cost of governing can be ‘party-specific’ in coalition governments. According to his argument, some parties may lose more votes than others when in power, depending on their ideological/programmatic profile. We concur with this interpretation and we adopt this ‘party-specific’ approach in our study. However, rather than analyzing different parties in government, we focus on the same party in different governing positions and at different territorial levels.

It has been shown that the cost of being in national government becomes even more significant when focusing on electoral results at the sub-national level. Indeed, regional elections have been widely regarded as ‘second-order’ elections (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). One of the main predictions of the second-order election (SOE) model is that national government parties tend to suffer electoral losses in regional elections. This happens because voters often use regional elections as an opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with the performance of the national government and to punish the national incumbent party (or parties in the case of coalitions) – this can be referred to as ‘barometer voting’. First established by Dinkel’s (Citation1977) seminal study on the German Länder, it has been subsequently validated by other studies (e.g. Jeffery and Hough Citation2001, Citation2006; Lohmann, Brady, and Rivers Citation1997; Müller Citation2018; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013; Völkl Citation2016).Footnote2

However, contrary to national ‘cost of governing’ and the punishment of national incumbents in regional elections expected by SOE, subnational incumbency tends to be associated with an electoral advantage (Ade, Freier, and Odendahl Citation2014; Freier Citation2015; Jankowski and Müller Citation2021; Kang, Park, and Song Citation2018; Kukołowicz and Górecki Citation2018). Even in highly decentralized federal systems, regional executives do not control key macroeconomic policies. Therefore, regional incumbency is likely to be less directly associated with voters’ changing evaluations of regional economic performance, which has also been shown to be strongly correlated with the performance of the national economy (Lohmann, Brady, and Rivers Citation1997, 431; Schakel Citation2015). As a result, regional governments appear to be more insulated from the negative electoral effects of economic downturns.

Although the literature suggests the existence of some (minimal) degree of economic voting at the sub-national level (Ebeid and Rodden Citation2006; Kukołowicz and Górecki Citation2018; León and Orriols Citation2016), Thorlakson’s (Citation2016:, 621) study on the German Länder has revealed that regional ‘coalition government dampens the impact of Land economic performance on the change in vote share of the incumbent senior coalition party at the Land level’. This makes economic voting largely irrelevant in regional elections.

While regional incumbents do not have much control over short- and medium-term economic policies and outcomes, they can still exploit other advantages stemming from their status as power-holders and the decentralized nature of electoral politics at the subnational level. These advantages include access to and distribution of regional resources, networking with key members of organizations that are particularly active/influential in regional society, increased media presence, name recognition, prestige and promotion of symbolic/identity-building initiatives, close relationship with constituents, and opposition to the national government regardless of party affiliation (Ade, Freier, and Odendahl Citation2014; Freier Citation2015; Kang, Park, and Song Citation2018). For all these reasons, it can be expected that regional incumbency, unlike national incumbency, has a positive impact on the electoral fortunes of a party.

The theoretical approaches outlined above are based on different assumptions and expectations, shedding light on some key aspects and electoral effects of incumbency. Yet what is still missing is a comprehensive framework that systematically links national and sub-national levels, emphasizing their interdependencies, while also recognizing the multiparty nature of regional and national executives in federal and decentralized systems.

In many European countries coalition politics has become much less predictable than it used to be until the 1980s. This unpredictability stems from the increasing volatility and fragmentation in both national and regional party systems. Italy serves as a clear example of the transformative effects brought about by new national and region-specific actors (Scantamburlo, Alonso, and Gómez Citation2018; Vampa Citation2015, Citation2023a). In Spain, coalitions used to be formed mainly in regions where state-wide and regionalist (or sub-state nationalist) parties coexisted. However, nowadays, multi-party governments have become the norm in all Autonomous Communities (Cabeza and Scantamburlo Citation2021; Simón Citation2020). In some contexts, once-dominant parties have moved into more subordinate positions. For example, in Germany, it is not uncommon for the SPD to be involved in regional coalition governments as a junior coalition partner (Bräuninger et al. Citation2020). This occurrence was relatively rare before German reunification. Generally, regional politics has become more competitive, and even highly consensual systems, like most of the Austrian ‘consociational’ Länder, have recently moved to less inclusive and more heterogeneous forms of coalition building (Praprotnik Citation2021).

Therefore, our assessment of the impact of incumbency needs to be more nuanced than that provided by previous studies, which have mainly focused on the electoral fortunes of ‘main’ incumbents (Lohmann, Brady, and Rivers Citation1997; Thorlakson Citation2016, Citation2020). We need to formulate incumbency hypotheses that take into account the more diverse roles parties play within regional governments, thus going beyond the simple ‘government vs opposition’ dichotomy.

Hypotheses

The literature on retrospective voting shows that the diluted structure of responsibility in multiparty cabinets often leads to major shifts in support within a ruling coalition, rather than between government and opposition parties (Anderson Citation1995). In a recent analysis, Klüver and Spoon (Citation2020) show that junior coalition partners may be punished for their participation in multiparty cabinets by suffering considerable electoral losses in the next election compared to their senior partners and to opposition parties. Considering the Merkel II cabinet between CDU/CSU and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) in Germany (2005–2009), their explanation is twofold. First, junior members of a coalition need to compromise with their senior partner, making it more challenging for them to fully deliver on their electoral promises and attract voters based on their government performance. Second, the blurring of responsibility in multiparty cabinets works against junior partners as they benefit less from media attention and are therefore less able to convey clear and distinct policy profiles to voters.

In their study on the collapse of the Liberal Democrats in the 2015 UK general election, Johnson and Middleton (Citation2016) also highlight the fact that junior coalition partners face a number of challenges, including the need to appear competent and retain the voters’ trust, while addressing the tension between governmental unity and party distinctiveness. In sum, we can expect junior coalition partners to be more exposed to the damaging effects of the growing gap between responsiveness to their core constituencies and governmental responsibility (Mair Citation2009) – particularly if they are involved in grand-coalitions led by their main electoral rivals.

Thus, the first question this article addresses is whether the same distribution of the costs of incumbency among coalition government partners can be expected at the regional level. We argue that the representation dynamics and the ‘vices’ of multi-level governance (Däubler, Müller, and Stecker Citation2020) provide multiple opportunities for leading regional parties to gain visibility and boost their profile mainly at the expense of smaller partners (but also parties in opposition).

In various decentralized and federal countries, the gradual decline in the significance of parliaments in comparison to governments at regional level (executive federalism), coupled with the dynamics of intergovernmental relations, has tended to favour the heads of regional executives and the parties they represent. In Germany, leaders of the Land governments, called Minister-Presidents (singular Ministerpräsident, plural Ministerpräsidenten), serve the dual function of head of government and head of state, which grants them considerable influence within and outside their respective regions (März Citation2006). Indeed, these key figures have privileged access to the federal arena via formal and informal institutions (Field Citation2014; Stecker Citation2015). Minister-Presidents can use their negotiating role at the national and supranational levels to dominate regional political debates and overshadow both junior allies and opposition.Footnote3 At the same time, they may become incredible assets for the largest parties in regional governments, to which they are generally affiliated, boosting their visibility.

All these dynamics are linked to the ‘personalization’ of regional politics (Jeffery and Hough Citation2001, 92), where frontrunners of main incumbent parties may have a significant advantage and ‘make a difference’ in electoral contests (Blumenberg and Blumenberg Citation2018, 373). This advantage may be amplified by the subordinate role of regional media landscapes to national ones and may be particularly noticeable during an election campaign (Tenscher and Schmid Citation2009). Indeed, as surveys show in the German case, Minister-Presidents are generally much more recognized by voters than the top candidates of their junior coalition partners or opposition candidates at the Land level.Footnote4

Finally, in multi-level systems, including regionalized/quasi-federal countries like Italy and Spain (Arban, Martinico, and Palermo Citation2021; León Citation2014), the clarity of government responsibility becomes even more blurred, and information asymmetries are greater compared to unitary/centralized systems. As a result, ‘passing the buck’ dynamics, attributing policy failures to other levels of government (León, Jurado, and Garmendia Citation2018), may increase the unequal cost of governing within coalition governments, favouring regional senior incumbents and further damaging junior partners. Our first hypothesis therefore is:

H1 Regional incumbency is positively associated with regional electoral performance, but only for the main governing party.

Therefore, the second question we address in the paper is whether the negative effect of national incumbency on a party’s regional election results is moderated by its incumbency position at the regional level. To our knowledge, this hypothesis has not been systematically tested in the literature. León (Citation2014) shows that in highly decentralized contexts, the coat-tail effects of national parties are reduced and regional parties become more detached from national politics. Generally, parties in regional government (either in a single-party government or in a coalition) tend to rely less on the electoral fortunes of their national co-partisans compared to opposition parties, which are more dependent on them. This is mainly because regional party branches with access to government resources are more autonomous in their campaign strategies and have more influence on the central party than regional parties in the opposition. Indeed, according to many studies on territorial organization (Fabre Citation2008; León Citation2017; Méndez-Lago Citation2005) the capacity of national leaders to have a tighter grip over regional party branches diminishes particularly against those leaders who have succeeded in holding regional office.

Since we have hypothesized that being in government as a senior incumbent (H1) is an advantage at the regional level, it is plausible that in decentralized contexts this advantage can counter the negative effects of being in national government because there are fewer electoral externalities, while being a junior incumbent does not have this advantage and may, in fact, lead to even worse outcomes. In sum, being the main regional incumbent – i.e. controlling regional resources combined with higher levels of visibility and autonomy from the centre – can help the regional branches limit defections of voters dissatisfied with the party in national government. Therefore:

H2 Leading the regional government reduces the (regional) electoral cost of being in national government.

Case selection: the SPD as a ‘lesson-drawing’ case study

In a seminal study assessing the effects of decentralization on electoral competition of state-wide parties, Sandra León (Citation2014) used electoral results of one key mainstream party, the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE), to draw more general lessons on how regional politicians’ electoral performance is correlated to that of their national counterparts. Similarly, in this study we focus on one party and test our hypotheses by examining the electoral results of what has long been considered an organizational and programmatic model in Europe: the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Specifically, we analyse its sub-national electoral performance at the ‘Land’ level over three decades after German reunification, from 1990 until 2020.

Similar to the PSOE, the SPD is a state-wide party competing in a highly decentralized institutional system. However, there are significant differences between Spain and Germany. Germany is a full-fledged federation, where the Länder have the same powers. Therefore, institutional asymmetries, as observed in Spain, are not present in the German context and the Länder are directly involved in national policy making through the Bundesrat (Turner Citation2011). Additionally, unlike Spain, where a wide range of non-state-wide parties (NSWPs) exist, Germany’s party system is much more nationalized. Even in Bavaria, where cultural differences have led to distinctive political dynamics, the regionalist Christian Social Union (CSU) has been consistently allied with its national ‘sister party’, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and can be regarded as a peculiar case of regionalist party (Müller Citation2018; Vampa and Scantamburlo Citation2021). As a result, the German context provides an opportunity to assess the multi-level effects of incumbency, while holding regional authority and the existence of regionalist and secessionist movements constant. In sum, while in León’s study, the focus was on how institutions and the competition of NSWPs affect the electoral fortunes of regional branches of a state-wide party, this study makes an additional and distinctive contribution to academic debates by looking at the interactions between different types of incumbency at both national and regional levels.

As mentioned in the introduction, the SPD is also a rare example of a mainstream party that has held all key positions within and outside government (main incumbent, junior incumbent, opposition) at both national and sub-national levels over the past thirty years. However, the fact that it is a ‘rare example’ does not necessarily imply that the SPD’s experience is entirely unique or not applicable in other contexts. Instead, in light of the ongoing de-institutionalization of European party politics (Chiaramonte and Emanuele Citation2022), we view the SPD as a ‘prototypical case’ (Cumming Citation2017; Hague, Harrop, and Breslin Citation2004), allowing us to test a new set of hypotheses. It stands as one of the first examples of a once-leading mainstream party that, due to significant electoral decline, has ended up occupying a variety of incumbency roles, including that of a junior coalition partner, on a regular basis. Given the challenges faced by many other established parties in multi-level European systems, the SPD may also be defined as a ‘lesson-drawing’ case study (Rose Citation1991). It is not yet representative, but it might become so: its present could be the future of many other parties.

Furthermore, it is essential to note that this is not a single case study from a strictly methodological standpoint (also refer to the methodological section below). Instead, we can draw numerous observations from the German SPD across the 16 Länder and over a span of 30 years. This extensive dataset allows us to conduct a cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative analysis. By focusing on one party, we can effectively assess the impact of incumbency while controlling for other party-specific characteristics, which distinguishes this study from van Spanje’s (2011) research, where different ideological/programmatic characteristics of the observations played a significant explanatory role.

In some respects, at least until 2021, the SPD represented one of the most advanced manifestations of the crisis of social democracy (Scantamburlo and Turner Citation2021) , which, along with the conservative/Christian democratic and liberal party families, forms the core of the European political mainstream. Throughout most of the post-2005 period, the party found itself trapped in national grand coalitions, resulting in a loss of over 10 million votes between its electoral peak of 1998 and 2017. It even appeared destined to be overtaken by the rising Green party as the dominant force within the left-wing camp. In essence, the SPD was paying a high price for being a ‘responsible’ governing party at the national level. Developments in 2021 surprised many observers as the SPD managed to win the federal election (Turner, Vampa, and Scantamburlo Citation2022, Citation2023). This article does not set out to identify the factors that led to this unexpected result. Rather, our starting point is that already before 2021, the SPD had managed to contain its electoral decline and even expand its support in some regional contexts.

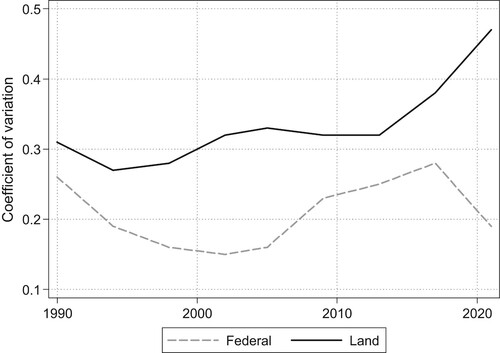

As shown in , since German reunification, the SPD’s electoral performance has been more regionally varied in Land elections than in federal elections. Territorial variation is measured by the coefficient of variation (CV) of the party’s electoral strength across the 16 Länder (Caramani Citation2004).Footnote5 The higher the CV the less evenly distributed the party’s electoral support is across the German territory. The black line in shows that the SPD’s performance in Land elections became even more heterogeneous after 2013. Therefore, the deep crisis experienced by the party at the national level in recent years did not affect all regions equally. This aspect is not of negligible importance. Indeed, by proving resilient in some contexts, the SPD could still rely on a core of strongholds and could sow the seeds for its nationwide electoral recovery in 2021. After all, Olaf Scholz – SPD Chancellor since 2021 – is himself the product of subnational electoral success: he managed to lead a recovering SPD in Hamburg, while the party kept losing elections at the federal level. Before him, in the 1990s, Gerhard Schröder played a similar role as electorally successful Prime Minister of Lower Saxony in the years of Helmut Kohl’s national dominance. There are other regional bastions – such as the prosperous and rather rural Rhineland Palatinate or the sparsely populated Mecklenburg-West Pomerania –, where, in spite of inauspicious demographics, the SPD has led the government for more than two decades. In sum, in ‘multi-level’ systems, the regional arena can become the last bulwark of resistance, a less exposed level of government where a nationally declining party can also prepare future comebacks.

Figure 1. Variation in SPD’s electoral support: comparing Land and federal results.

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on data provided by the Federal Returning Officer (https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/).

The gap between national and regional results suggests that the cost of governing may be different depending on the territorial level considered. In fact, as we empirically show below, regional incumbency may provide electoral benefits, which counteract the negative effects of participation in national government. Moreover, a distinction should be made between different types of incumbency: leading a government is different from being a junior coalition partner. In the latter case the more limited ability to shape the policy agenda, the lack of visibility and the need to compromise with the senior partner and act responsibly may have a negative impact on electoral results at all territorial levels.

Data and methodology

To test the different effects of incumbency types on the SPD’s regional electoral success, we use the vote share that all single Land branches of the SPD receive at the next election (t1) as our dependent variable. We also control for the vote share at the current election (t0) to take into account the prior level of electoral success. As a robustness check, following Thorlakson (Citation2016), we computed a measure of vote change by subtracting the vote share of the SPD at the next election (t1) from its vote share at the current election (t0).Footnote6 Since this alternative dependent variable specification yields the same results (see Table A3 in the Appendix) we rely on the absolute vote share. Data were obtained from the Federal Returning Officer. Table A1 in the Appendix shows how the dependent variable varies by government status.

In order to examine the effects of different incumbency types (main vs. junior) on the SPD’s electoral prospects in regional elections depending on the political level (Federal and Land), we use two categorical government status variables that distinguish between different types of incumbencies. Land incumbency is a categorical variable indicating whether the SPD is the main ruling party (code 1), junior ruling party (code 2) or opposition party (code 3) in the respective Land. Federal incumbency indicates whether the SPD is the main ruling party (code 1), junior ruling party (code 2) or opposition party (code 3) at the federal level. Following Klüver and Spoon (Citation2020, 1234) we define coalition parties as those parties that ‘share executive offices with at least one other party’ and distinguish between senior (or main) and junior coalition partners by the partisan affiliation of the Prime Minister: ‘While the Prime Minister is affiliated with the senior coalition party, all other coalition parties not controlling the Prime Minister position are junior members of the coalition’.Footnote7 We use junior incumbency as the reference category since we are particularly interested in understanding how it differs from senior incumbency, and it can be seen as an intermediate category between government leadership and opposition.

We control for a number of additional variables that may potentially confound the hypothesized relationship. First, given that research on barometer voting has shown that the timing of the electoral cycle predicts the punishing effect of federal incumbent parties we include a timing variable measured as the distance in years from the mid-point of the federal electoral cycle.Footnote8 The SOE model predicts a curvilinear relationship the closer the subnational election is to the midpoint of the federal electoral cycle the stronger the predicted punishment effect for the federal incumbent party (Dinkel Citation1977; Thorlakson Citation2016).

Since poor economic conditions have been linked with decreasing vote shares of mainstream parties and the rise of challengers at both national and regional levels (Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016; Scantamburlo, Alonso, and Gómez Citation2018), we next control for macroeconomic indicators of government performance typical of the economic voting literature such as the changes in GDP per capita and unemployment rate. Both derive from the Annual Regional Database of the European Commission (ARDECO) and the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt). Following established research on territorial politics (Sorens Citation2005) we rely on relative measures i.e. the relative difference in income/unemployment between the region and the whole country.Footnote9

Third, we include a measure for party policy positioning on the Left-Right dimension. In contexts of strong regional government, sub-national branches of the same party may use their autonomy to develop differentiated policy agendas that allow them to adapt their electoral pledges to the specific demands of regional constituencies and thus continue to win votes across the whole country (Alonso and Gómez Citation2011; León and Scantamburlo Citation2023). German subnational party organizations have been particularly keen in using their relatively strong autonomy when drafting their programmes (Stecker Citation2015). Following the literature (Alonso et al. Citation2012; Däubler Citation2012; Dolezal et al. Citation2012; Gross, Krauss, and Praprotnik Citation2023; Scantamburlo Citation2019), we choose subnational parties’ election manifestos as the main documents to measure party policy positions in regional elections for at least three reasons: first, manifestos are ‘authoritative statements of party preferences and represent the whole party, not just one faction or politician’ (Alonso et al. Citation2012, 1). Second, manifestos are published regularly for each election, which enables a systematic comparison of programmatic changes over time and space. Third, manifestos not only serve as base documents for citizens’ voting decisions, but also for intra-party purposes by signalling issue positions to members and supporters.Footnote10 We measure policy positions in the respective election with new data obtained from a content analysis of all regional SPD manifestos from 1990 to 2020 using the Regional Manifestos Project’s (RMP) coding scheme. The RMP’s content analysis methodology is an adaptation of the Manifesto Research on Political Representation’s (MARPOR) classification scheme, developed for multilevel polities. This adaption is explained in Alonso, Gómez, and Cabeza (Citation2013). We use the classic RILE scale developed by MARPOR (Laver and Budge Citation1992), which ranges from −100 (far left) to 100 (far right).Footnote11

Fourth, vote gains and losses of left competitor parties, radical left and new politics parties alike, have been shown to impact the electoral support of the mainstream left (Kitschelt Citation1994). Thus, following research on left parties’ electoral performance (Krause Citation2020; Polacko Citation2022) we add the variable left competitors, a continuous measure indicating the vote share gained by the SPD’s main left-wing rival parties – the Greens and the PDS/Linke – in the election in question.Footnote12

Finally, we include a dummy control variable for East Germany (0 = West; 1 = East) to account for the large differences in the party systems between Eastern and Western Germany, with the former being generally more electorally volatile than the latter (Vampa Citation2023a).Footnote13

The multivariate linear model is tested by relying on a dataset that consists of 114 elections in all 16 German Länder in the period from 1990–2020. The descriptive statistics of the numerical dependent and independent variables used in the statistical analysis are included in . For the categorical variables on SPD incumbency status see descriptive statistics in the appendix (Table A1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

To test our hypotheses, it is necessary to take into account the structure of the data. Our observations are clustered into 16 Länder. It means that the observations are not independent. In order to account for this, we employ a panel data generalized least squares (GLS) regression with clustered robust standard errors by Land. In addition to the clustering, the dataset is also characterized by a time component as we analyse succeeding elections. To control for potential autocorrelation induced by the time series structure of the data, we include a lagged dependent variable (Beck and Katz Citation1995; Beck Citation2001). We have also performed various robustness checks (see Appendix, Tables A1 and A2), which confirmed (and, in some cases, even reinforced) the results presented below.

Results

The results of the regression analysis are presented in . Model 1 (SOE Model) includes all variables apart from Land incumbency. Model 2 tests hypothesis 1 by introducing the Land incumbency status. Model 3 adds an interaction effect between regional and federal incumbency to test H2.

Table 2. Explaining SPD’s electoral performance at the Land level.

Looking at Model 1 we observe a strong positive effect when the SPD is in opposition at the federal level as opposed to being junior partner (reference category), while we do not see a statistically significant effect of SPD when it is the leading federal party. This is in line with the second-order nature of Land elections (‘barometer voting’) rewarding parties that are in opposition at the federal level (regardless of time in the electoral cycle). Apart from the expected significance of the lagged dependent variable, we observe no significant effect of control variables.

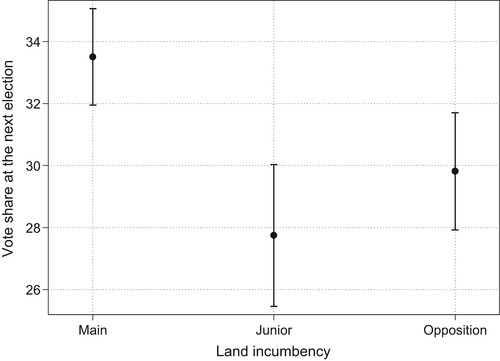

When including Land incumbency variables in Model 2 we see the opposite pattern: a strong and statistically significant effect of the ‘Main incumbent’ category (H1). An average of almost 6-percentage-point bonus is expected for SPD if it leads the incumbent Land government compared to SPD junior partner in incumbent land government (reference category) and well above 3-percentage points compared to opposition parties. There is a positive effect also if the SPD is in opposition compared to junior ruling party, but it is not statistically significant. Generally, the SPD benefits from the incumbency bonus when it leads the government in regional elections, while it performs worst when it acts as junior ruling party.

To further illustrate the effect of main incumbency on a party’s electoral success, we have simulated predicted values as suggested by Brambor, Clark, and Golder (Citation2006). displays the predicted vote share at the next regional election depending on the government status of a party while all other variables are held at their mean (continuous variables) or median (categorical variables) values. clearly shows that when the SPD is a junior coalition partner or in opposition at the regional level, it is significantly less successful in the subsequent election than when it is a senior incumbent, controlling for all other variables, including previous vote share. It is therefore clear that the ‘cost of governing’ argument only applies to the national level, whereas leading the regional executive produces significant electoral benefits in regional elections.

Figure 2. Predicted SPD vote share by incumbency status at the regional (Land) level. Note: Predicted values based on Model 2.

Although our theoretical framework does not consider additional moderating effects, we have conducted some exploratory analyses. For instance, we explored the potential moderating impact of regional economic conditions on the electoral performance of a regionally incumbent party. It may be argued that poor economic performance affects the success of the senior coalition partner more than the junior partner, as the former tends to bear more blame for the economic downturn. To investigate this argument, we re-ran our analysis with an interaction term between regional incumbency and economic performance, measured by changes in GDP and the unemployment rate (refer to Table A2 and Figures A2a and A2b in the Appendix for details). The results indicate that economic conditions do not appear to significantly influence the success of the SPD when it holds a regional senior incumbency, which aligns with existing literature that suggests the absence of significant economic voting at the sub-national level, particularly in a context of coalition governments. However, there seems to be some effect on the SPD as a junior partner. Surprisingly, when the economy goes comparatively well, the regional SPD is more penalized than at times of economic downturn or stagnation.Footnote14 This intriguing result – perhaps due to the fact that, as junior partner, the SPD may not be seen as owner of economic issues – reverses the ‘grievance asymmetry’ identified by other ‘cost of governing studies’ and warrants further investigation in future research.

We have also re-run our analysis with an interaction term between regional incumbency and our timing variables (Table A3 and Figures A3a and A3b in the Appendix for details). Results do not point to very large effects, but we can see that differences between senior and junior partner increase the more regional elections move further away from the following national election. Conversely, in regional elections held during the federal election year, there do not seem to be significant differences between incumbency categories. However, it is important to note that this minor finding is not the primary focus of our hypotheses, and therefore, it could be further explored and explained using more elaborate models in future studies.

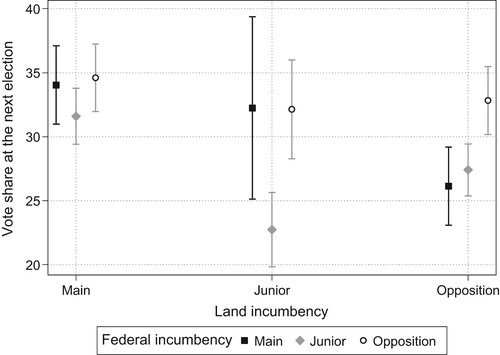

We now turn to the key question of whether the senior incumbency advantage at the regional level is able to mitigate the cost of governing at the national level. To test H2, Model 3 in includes an interaction effect between regional and national incumbency. Since it is difficult to interpret the different interaction coefficients (Brambor, Clark, and Golder Citation2006), we rely on predictive margins. , based on Model 3, shows how the performance of the SPD is expected to change for different combinations of incumbency (while all other independent variables are held constant at mean and median values).

Figure 3. Predicted SPD vote share by incumbency status at regional (Land) and federal levels. Note: Predicted values based on Model 3.

When the SPD is in opposition at the federal level, it appears to perform better in regional elections regardless of its regional incumbency status (grey margins with white circle marker). This latter result is consistent with the ‘second-order’ character of regional elections, which tend to reward national opposition parties. Yet the opposite – electoral punishment for being a national governing party – is true only under certain conditions. Leading regional government seems to play a particularly important role in allowing the SPD to remain electorally competitive when it is a junior governing party at the national level. Instead, we observe a significant drop in support when the party holds junior incumbency at both regional and federal levels (grey margins with grey diamond markers). This ‘in-between’ category seems to be the worst scenario for the SPD, where the party neither leads nor opposes federal and regional executives. Electoral decline is also clearly visible when the SPD leads the national executive and switches from the role of regional leading party to that of opposition (black margins with square marker). Thus, voters tend to punish a national leading party – and the second-order effect expectation is confirmed – especially if the same party is in opposition at the regional level. In this scenario, the SPD may be perceived as an ‘ineffective’ or ‘inauthentic’ regional opposition, as it still represents the party in central government and is likely to be influenced by its decisions. On the other hand, when the SPD leads at the Land level, it can rely on more visibility and autonomy in setting a distinctive agenda to distance itself from central government, even when the latter is controlled by co-partisans.

In sum, we have shown that governing means different things at different territorial levels. The cost of governing at the national level is significantly reduced if a party controls the leadership of the regional government. However, occupying subordinate positions in both regional and national governments – i.e. being a junior coalition partner at both levels – amplifies the cost of governing, producing an electoral collapse in regional elections.

Conclusion

How do the electoral costs of incumbency change depending on what role a party plays in government? Does multi-level governance contribute to mitigate the costs of incumbency? Looking at the effects of incumbency on electoral performance at the regional level, we have tried to answer these questions by arguing that incumbency has varying effects depending on whether a party is a leading or a junior coalition partner (horizontal dimension), as well as the territorial level of its incumbency (vertical dimensions). We hypothesized that regional incumbency is positively associated with electoral performance at the regional level, but only for the main governing party. Additionally, we established the hypothesis that in decentralized contexts this advantage can counter the negative effects of being in national government expected by the SOE model. The relevance of looking at these dimensions is threefold. First, we fill a gap by looking at the largely unexplored impact of varying types of regional incumbency on regional electoral performance. Second, we offer a more nuanced theoretical and empirical account of the SOE model and its predictions concerning the effects of national incumbents in regional elections. Finally, by shedding light on the complexities of governing in multi-level political systems, we contribute to the recent debate on democratic accountability and the virtues and vices of multi-level governance (Däubler, Müller, and Stecker Citation2020).

The empirical analysis has been based on the electoral performance of the SPD, a rare example of a mainstream party that has held all governmental roles at both national and regional levels, in more than 100 Land elections over three decades after German reunification, from 1990 until 2020. Broadly speaking, this is a correlational study and, as such, it has allowed us to show how the SPD did when being a certain type of incumbent. While alternative statistical methods could be used to determine precise cause-and-effect relationships, our empirical analysis suggests that regional leadership may play an important role in shaping a party’s ‘multi-level’ electoral fortunes. Regional incumbency can be an asset, significantly reducing the cost of governing typically associated with being in central government. Specifically, the SPD demonstrated greater resilience in contexts where it retained control of the regional executive while being more electorally vulnerable at the national level.

Moreover, we have hinted at other potential moderating factors that could influence the effect of incumbency. Economic conditions and election timings do not seem to play a big role. Yet other factors, such as programmatic positions may interact with the effect of incumbency. In additional tests that have not been included in the analysis for the sake of parsimony and clarity, programmatic radicalism seems to be particularly costly when a mainstream party like the SPD plays a secondary role in government and has to compromise with a senior coalition partner. These preliminary results can be further explored in future studies uncovering additional complexities of multi-level electoral politics.

Ultimately, a focus on Germany and the SPD has enabled us to test new hypotheses regarding the performance of mainstream parties in political systems with multiple opportunities for government at different territorial levels. In 2021 the SPD returned to a leading position at the national level after having been relegated to an ancillary role for many years (Turner, Vampa, and Scantamburlo Citation2022, 2023). However, even at the height of its electoral crisis, the party managed to remain a successful governmental actor in some regional contexts. The SPD demonstrates that regional leaders and control of regional resources can help a party survive and rebuild its electoral appeal. A future analysis could consider the other main German party, the CDU, which is now in opposition after a long time leading central government, and see whether results converge with those we have found for the SPD.

Similar stories could also unfold in other European countries. For example, in the UK, the Labour party leads a devolved nation (Wales) and can rely on a network of metro-mayors and other subnational leaders – including some in the former ‘red wall’ (Mattinson Citation2020) – who can significantly contribute to improving the party’s chances of electoral recovery. In Spain the mainstream Socialists and Popular Party showed significant resilience also thanks to their leading role in regional government. Additionally, they mitigated the threat posed by new competitors such as Ciudadanos and Podemos (and even Vox) by incorporating them into coalitions as junior partners. In Italy, the centre-left Democratic Party (PD) managed to temporarily halt the rise of right-wing populists and simultaneously stop its own electoral decline, thanks to the victory of its incumbent government in the Emilia Romagna region in early 2020 (Vampa Citation2021). Even today, despite facing a new populist wave embodied by Giorgia Meloni’s radical right Brothers of Italy (Vampa Citation2023b), the PD continues to play a leading role in four key Italian regions. The loss of these remaining strongholds could push the party to the brink of irreversible decline.

In conclusion, regional incumbency presents a crucial political resource for struggling mainstream parties. Aspiring to regain national prominence, they should continue playing a leading role in regional governments and strengthen their ties with sub-national communities. By leveraging regional leadership and resources, these parties can enhance their electoral prospects and effectively navigate the complexities of multi-level electoral politics.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (88 KB)Acknowledgements

The research for and write-up of this paper have been supported by the German Academic Exchange System (DAAD). Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the PSA Annual International Conference (University of York 2022), the IASGP Annual Conference (University of Düsseldorf 2022), and the Workshop “Innocent or guilty? The role of political parties in rebuilding representative democracy. A reflection on Peter Mair's work” (Robert Schuman Centre, Florence 2022). For insightful comments and other help, we would like to thank Sonia Alonso, Matthias Dilling, Joost Van Spanje, Mariana Sendra, and the three anonymous reviewers. Their comments have significantly contributed to enhancing the overall quality of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It should also be clarified that throughout the article the terms ‘national’, ‘federal’, ‘nation’, ‘federation’ are all used to refer to central government. Equally, ‘region’, ‘state’, ‘Land’, ‘regional’ refer to the 16 sub-national units – the Länder – that form the German federation.

2 Since Dinkel’s (Citation1977) seminal study this literature has widely acknowledged that the cost of governing varies according to the placement of the second-order election in the first-order election cycle with a peak around the middle of the legislative period.

3 Stecker (Citation2015) shows for the German case that the more ambitious Minister-Presidents are with regard to the federal level, the more the representatives of their Land engage in federal-level activities such as bringing in bills to the Bundesrat.

4 Trend surveys conducted between 2022 and 2023 for Länder that held elections in the 2019–2022 period reveal that Minister-Presidents enjoy public recognition scores around 90%, whereas leading candidates of junior partners typically range between 60-70%. The most significant gaps are observed in coalitions involving more than two parties. In Thuringia and Brandenburg, for instance, recognition of junior partners’ leading candidates doesn’t even reach 50%. Source: https://www.infratest-dimap.de/

5 The Coefficient of Variation (CV) here is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation and the average electoral results of the SPD across the 16 Länder.

6 Values above 0 indicate electoral gains for the SPD and values below 0 indicate electoral losses. A value of 0 indicates that the SPD obtained the same vote share as in the current election.

7 At the national level there has not been any SPD single government whereas at the regional level there were 18 SPD single governments within the time frame of analysis. We include these within the category of senior incumbents. Table R3 in the appendix performs the analyses without single governments. The effects are amplified indicating that incumbency advantage for senior incumbents is stronger in coalition governments.

8 As a robustness check, we have also used an alternative electoral cycle measure proposed by Gross and Chiru (Citation2022, 488) calculated as the number of days between a national election the next regional election, divided by the total number of days of the national electoral cycle (see Table A6 in the Appendix). The results are substantially the same.

9 Table R4 in the appendix includes an analysis with absolute, i.e. Land, values. The results are substantially the same.

10 Manifestos play a major role in (party) political theory. In particular, the model of responsible party government assumes parties to offer clear programmatic alternatives to voters and to implement their promises as soon as they assume government responsibility (Alonso et al. Citation2012).

11 As a robustness check, we have also estimated the left-right positions based on the so-called log transformation scale (Lowe et al. Citation2011) and on separated positional scales for the economic and cultural dimensions using the items defined by MARPOR (https://manifestoproject.wzb.eu). Moreover, we have estimated an additional model using the Wordscores estimations by Bräuninger et al. (Citation2020). The results are substantially the same (see Table A5 in the Appendix).

12 Following Abou-Chadi and Wagner’s (Citation2019) seminal work on mainstream left parties’ electoral performance we include binary measures for the presence of radical left and right parties in the outgoing Land parliament as a robustness check (see Table A6 in the Appendix). The results are substantially the same.

13 In a separate model (see Table A6) we also have removed the control for Eastern Germany. The results are substantially the same.

14 When the economy did comparatively well, the SPD lost votes as junior coalition partner in Baden-Württemberg in 1996, Saxony in 2019, Schleswig-Holstein in 2009 and Thuringia in 1999 and 2014, while it has been even able to win votes in Berlin (2001) and Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (1998) despite an economy faring comparatively worse.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T., and M. Wagner. 2019. “The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Postindustrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?.” The Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1405–1419. doi: 10.1086/704436

- Ade, F., R. Freier, and C. Odendahl. 2014. “Incumbency Effects in Government and Opposition: Evidence from Germany.” European Journal of Political Economy 36:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.07.008

- Albertazzi, D., and D. McDonnell. 2015. Populists in Power. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Alonso, S., and B. Gómez. 2011. “Partidos Nacionales en Elecciones Regionales: ¿Coherencia Territorial o Programas a la Carta?” Revista de Estudios Políticos 152:183–209.

- Alonso, S., B. Gómez, and L. Cabeza. 2013. “Measuring Centre–Periphery Preferences: The Regional Manifestos Project.” Regional & Federal Studies 23 (2): 189–211. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2012.754351

- Alonso, S., A. Volkens, L. Cabeza, and B. Gómez. 2012. The Content Analysis of Manifestos in Multilevel Settings. Exemplified for Spanish Regional Manifestos. WZB Discussion Paper, No. SP IV 2012-201, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Anderson, C. J. 1995. “The Dynamics of Public Support for Coalition Governments.” Comparative Political Studies 28 (3): 350–383. doi: 10.1177/0010414095028003002

- Arban, E., G. Martinico, and F. Palermo, eds. 2021. Federalism and Constitutional Law. The Italian Contribution to Comparative Regionalism. London: Routledge.

- Beck, N. 2001. “Time-Series-Cross-Section Data: What Have we Learned in the Past Few Years?” Annual Review of Political Science 4:271–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.271

- Beck, N., and J. N. Katz. 1995. “What to do (and not to do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 634–647. doi: 10.2307/2082979

- Bloom, H. S., and H. D. Price. 1975. “Voter Response to Short-run Economic Conditions: The Asymmetric Effect of Prosperity and Recession.” American Political Science Review 69:1240–1254. doi: 10.2307/1955284

- Blumenberg, J. N., and M. S. Blumenberg. 2018. “The Kretschmann Effect: Personalisation and the March 2016 Länder Elections.” German Politics 27 (3): 359–379. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2017.1342814

- Brambor, T., W. R. Clark, and M. Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpi014

- Bräuninger, T., M. Debus, J. Müller, and C. Stecker. 2020. Parteienwettbewerb in den Deutschen Bundesländern. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Cabeza, L., and M. Scantamburlo. 2021. “Dual Voting and Second-Order Effects in the Quasi-Simultaneous 2019 Spanish Regional and National Elections.” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 55:13–35. doi: 10.21308/recp.55.01

- Caramani, D. 2004. The Nationalization of Politics. The Formation of National Electorates and Party Systems in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chiaramonte, A., and V. Emanuele. 2022. The Deinstitutionalization of Western European Party Systems. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cumming, G. 2017. “A Prototypical Case in the Making? Challenging Comparative Perspectives on French Aid.” The European Journal of Development Research 29 (1): 19–36. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2015.62

- Däubler, T. 2012. “The Preparation and Use of Election Manifestos: Learning from the Irish Case.” Irish Political Studies 27 (1): 51–70. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2012.636183

- Däubler, T., J. Müller, and C. Stecker. 2020. Democratic Representation in Multi-Level Systems: The Vices and Virtues of Regionalisation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Detterbeck, K. 2012. Multi-level Party Politics in Western Europe. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dinkel, R. 1977. “Der Zusammenhang Zwischen Bundes- und Landtagswahlergebnissen.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 18:348–360.

- Dolezal, M., L. Ennser-Jedenastik, W. C. Müller, and A. K. Winkler. 2012. “The Life Cycle of Party Manifestos: The Austrian Case.” West European Politics 35 (4): 869–895. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.682349

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Ebeid, M., and J. Rodden. 2006. “Economic Geography and Economic Voting: Evidence from the US States.” British Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 527–547. doi: 10.1017/S0007123406000275

- Fabre, E. 2008. “Party Organization in a Multi-Level System: Party Organizational Change in Spain and the UK.” Regional & Federal Studies 18 (4): 309–329. doi: 10.1080/13597560802223896

- Field, B. N. 2014. “Minority Parliamentary Government and Multilevel Politics: Spain's System of Mutual Back Scratching.” Comparative Politics 46 (3): 293–312. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041514810943090.

- Freier, R. 2015. “The Mayor's Advantage: Causal Evidence on Incumbency Effects in German Mayoral Elections.” European Journal of Political Economy 40:16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.07.005

- Gross, M., and M. Chiru. 2022. “Time is on my Side? The Temporal Proximity Between Elections and Parties’ Salience Strategies.” European Political Science Review 14 (4): 482–497. doi: 10.1017/S1755773922000376

- Gross, M., S. Krauss, and K. Praprotnik. 2023. “Electoral Strategies in Multilevel Systems: The Effect of National Politics on Regional Elections.” Regional Studies 57 (5): 844–856. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2022.2107193

- Hague, R., M. Harrop, and S. Breslin. 2004. Comparative Government and Politics: An Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hobolt, S., and J. Tilley. 2016. “Fleeing the Centre: The Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis.” West European Politics 39 (5): 971–991. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

- Jankowski, M., and S. Müller. 2021. “The Incumbency Advantage in Second-Order PR Elections: Evidence from the Irish Context, 1942–2019.” Electoral Studies 71:102331. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102331

- Jeffery, C. 2008. “The Challenge of Territorial Politics.” Policy & Politics 36 (4): 545–557. doi: 10.1332/147084408X349800

- Jeffery, C., and D. Hough. 2001. “The Electoral Cycle and Multi-Level Voting in Germany.” German Politics 10 (2): 73–98. doi: 10.1080/772713264

- Jeffery, C., and D. Hough. 2006. “Devolution and Electoral Politics: Where Does the UK Fit In?” In Devolution and Electoral Politics, edited by D. Hough and C. Jeffery, 248–256. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Johnson, C., and A. Middleton. 2016. “Junior Coalition Parties in the British Context: Explaining the Liberal Democrat Collapse at the 2015 General Election.” Electoral Studies 43:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.05.007

- Kang, W. C., W. Park, and B. K. Song. 2018. “The Effect of Incumbency in National and Local Elections: Evidence from South Korea.” Electoral Studies 56:47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.09.005.

- Katz, R., and P. Mair. 2018. Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Klüver, H., and J. Spoon. 2020. “Helping or Hurting? How Governing as a Junior Coalition Partner Influences Electoral Outcomes.” The Journal of Politics 82 (4): 1231–1242. doi: 10.1086/708239

- Krause, W. 2020. “Appearing Moderate or Radical? Radical Left Party Success and the two-Dimensional Political Space.” West European Politics 43 (7): 1365–1387. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1672019

- Kukołowicz, P., and M. A. Górecki. 2018. “When Incumbents Can Only Gain: Economic Voting in Local Government Elections in Poland.” West European Politics 41 (3): 640–659. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1403147

- Laver, M., and I. Budge, eds. 1992. Party Policy and Government Coalitions. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- León, S. 2014. “How Does Decentralization Affect Electoral Competition of State-Wide Parties? Evidence from Spain.” Party Politics 20 (3): 391–402. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436044

- León, S. 2017. “Territorial Cleavage or Institutional Break-up? Party Integration and Ideological Cohesiveness among Spanish Elites.” Party Politics 23 (3): 236–247. doi: 10.1177/1354068815588459

- León, S., I. Jurado, and A. Garmendia. 2018. “Passing the Buck? Responsibility Attribution and Cognitive Bias in Multilevel Democracies.” West European Politics 41 (3): 660–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1405325.

- León, S., and L. Orriols. 2016. “Asymmetric Federalism and Economic Voting.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (4): 847–865. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12148

- León, S., and M. Scantamburlo. 2023. “Right-wing Populism and Territorial Party Competition: The Case of the Alternative for Germany.” Party Politics 29 (6): 1051–1062. doi: 10.1177/13540688221122336

- Lohmann, S., D. V. Brady, and D. Rivers. 1997. “Party Identification, Retrospective Voting, and Moderating Elections in a Federal System.” Comparative Political Studies 30 (4): 420–449. doi: 10.1177/0010414097030004002

- Lowe, W., K. Benoit, S. Mikhaylov, and M. Laver. 2011. “Scaling Policy Preferences from Coded Political Texts.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 36 (1): 123–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-9162.2010.00006.x

- Mair, P. 2009. Representative Versus Responsible Government. MPIfG Working Paper, 09/8. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Manwaring, R., and P. Kennedy, eds. 2017. Why the Left Loses: The Decline of the Centre-Left in Comparative Perspective. Bristol: Policy Press.

- März, P. 2006. “Ministerpräsidenten.” In Landespolitik in Deutschland. Grundlagen - Strukturen - Arbeitsfelder, edited by H. Schneider, 148–184. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Mattinson, D. 2020. Beyond the Red Wall. London: Biteback Publishing.

- Méndez-Lago, M. 2005. “The Socialist Party in Government and Opposition.” In The Politics of Contemporary Spain, edited by S. Balfour, 169–197. London: Routledge.

- Mueller, J. E. 1970. “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955610.

- Müller, J. 2009. “The Impact of the Socio-Economic Context on the Länder Parties’ Policy Positions.” German Politics 18 (3): 365–384. doi: 10.1080/09644000903055815

- Müller, J. 2018. “German Regional Elections: Patterns of Second-Order Voting.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 301–324. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2017.1417853

- Paldam, M. 1986. “The Distribution of Election Results and the Two Explanations of the Cost of Ruling.” European Journal of Political Economy 2 (1): 5–24. doi: 10.1016/S0176-2680(86)80002-7

- Paldam, M., and P. Skott. 1995. “A Rational-Voter Explanation of the Cost of Ruling.” Public Choice 83 (1-2): 159–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01047690

- Polacko, M. 2022. “The Rightward Shift and Electoral Decline of Social Democratic Parties Under Increasing Inequality.” West European Politics 45 (4): 665–692. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2021.1916294

- Powell, G. B., and G. D. Whitten. 1993. “A Cross-National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context.” American Journal of Political Science 37 (2): 391–414. doi: 10.2307/2111378

- Praprotnik, K. 2021. Das Proporzsystem: Wenn (Fast) Alle in der Regierung Sitzen. Austrian Democracy Lab Blog https://www.austriandemocracylab.at/das-proporzsystem-wenn-fast-alle-in-der-regierung-sitzen/

- Reif, K., and H. Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections – A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results.” European Journal of Political Research 8 (1): 3–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- Rose, R. 1991. “Comparing Forms of Comparative Analysis.” Political Studies 39 (3): 446–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1991.tb01622.x

- Rose, R., and T. Mackie. 1983. “Incumbency in Government: Asset or Liability?” In Western European Party Systems: Continuity and Change, edited by H. Daalder and P. Mair, 115–138. London: Sage.

- Scantamburlo, M. 2019. “Who Represents the Poor? The Corrective Potential of Populism in Spain.” Representation 55 (4): 415–434. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1669692

- Scantamburlo, M., S. Alonso, and B. Gómez. 2018. “Democratic Regeneration in European Peripheral Regions: New Politics for the Territory?” West European Politics 41 (3): 615–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1403148.

- Scantamburlo, M., and E. Turner. 2021. “Germany and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands.” In Europe and the Left. Resisting the Populist Tide, edited by J. L. Newell, 123–143. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schakel, A. H. 2015. “How to Analyze Second-Order Election Effects? A Refined Second-Order Election Model.” Comparative European Politics 13 (6): 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2014.16.

- Schakel, A. H., and C. Jeffery. 2013. “Are Regional Elections Really ‘Second-Order’ Elections?” Regional Studies 47 (2): 323–341. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.690069

- Simón, P. 2020. “The Multiple Spanish Elections of April and May 2019: The Impact of Territorial and Left-Right Polarisation.” South European Society and Politics 25 (3-4): 441–474. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2020.1756612

- Sorens, J. 2005. “The Cross-Sectional Determinants of Secessionism in Advanced Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (3): 304–326. doi: 10.1177/0010414004272538

- Stecker, C. 2015. “Parties on the Chain of Federalism: Position-Taking and Multi-level Party Competition in Germany.” West European Politics 38 (6): 1305–1326. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1029366

- Strøm, K. 1990. Minority Government and Majority Rule. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Tenscher, J., and S. Schmid. 2009. “Berichterstattung Nach Wahl. Eine Vergleichende Analyse von Bundes- und Landtagswahlkämpfen in der Regionalpresse.” Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 57 (1): 56–77. doi: 10.5771/1615-634x-2009-1-56

- Thorlakson, L. 2016. “Electoral Linkages in Federal Systems: Barometer Voting and Economic Voting in the German Länder.” Swiss Political Science Review 22 (4): 608–624. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12226

- Thorlakson, L. 2020. Multi-Level Democracy: Integration and Independence Among Party Systems, Parties, and Voters in Seven Federal Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Turner, E. 2011. Political Parties and Public Policy in the German Länder: When Parties Matter. Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Turner, E., D. Vampa, and M. Scantamburlo. 2022. “From Zero to Hero? The Rise of Olaf Scholz and the SPD.” German Politics and Society 40 (3): 127–147. doi: 10.3167/gps.2022.400307

- Turner, E., D. Vampa, and M. Scantamburlo. 2023. “The SPD and the 2021 Federal Election.” In The 2021 German Federal Election, edited by R. Campbell and L. K. Davidson-Schmich, 61–79. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vampa, D. 2015. “The 2015 Regional Election in Italy: Fragmentation and Crisis of Subnational Representative Democracy.” Regional & Federal Studies 25 (4): 365–378. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2015.1074073

- Vampa, D. 2021. “The 2020 Regional Elections in Italy: Sub-National Politics in the Year of the Pandemic.” Contemporary Italian Politics 13 (2): 166–180. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2021.1912301

- Vampa, D. 2023a. “Multi-level Political Change: Assessing Electoral Volatility in 58 European Regions (1993-2022).” Party Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231176052.

- Vampa, D. 2023b. Brothers of Italy: A New Populist Wave in an Unstable Party System. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vampa, D., and M. Scantamburlo. 2021. “The ‘Alpine Region’ and Political Change: Lessons from Bavaria and South Tyrol (1946-2018).” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (5): 625–646. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2020.1722946

- van Spanje, J. 2011. “Keeping the Rascals in: Anti-Political-Establishment Parties and Their Cost of Governing in Established Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (5): 609–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01984.x

- Völkl, K. 2016. “Länder Elections in German Federalism: Does Federal or Land-Level Influence Predominate?” German Politics 25 (2): 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2016.1157863.