ABSTRACT

To achieve foreign policy goals and boost prestige, states try to influence how foreign publics perceive them. Particularly during crises, the imperative to mitigate a negative image may see states mobilize resources to change the global narrative. This paper investigates whether China’s ‘mask diplomacy' efforts influenced portrayals of the country in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. We validate and apply a semi-supervised scaling method to 1.5 million English statements in newspapers around the world mentioning China and Covid-19. Multi-period difference-in-differences models reveal that media tone improved significantly after mask diplomacy engagement. Using its Covid-19 White Paper to determine China’s preferred external narratives, we also find that a country’s domestic media reproduced key terms more after the country received PRC support.

Introduction

Throughout 2020 and 2021, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić was not shy about publicizing the fact that his country imported medical equipment, teams of doctors, and vaccines from the People’s Republic of China (PRC). He showed up at the Belgrade airport to welcome the aid and even kissed the PRC flag in gratitude. Vučić received glowing coverage in China’s official press and gave an interview for Xinhua in which he spoke about the PRC’s generosity, explaining: ‘I went to the airport, I waited for the goods … whether they were ventilators or vaccines and I did say many thanks to our Chinese friends' (Xinhua Citation2021).

Serbia was not the only recipient of Chinese medical provisions during the initial stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. Beijing engaged in this sort of ‘mask diplomacy' (i.e. the public provision of Covid-19 medical assistance or supplies) with many states around the world in the six months following the outbreak of the disease (Fuchs et al. Citation2021). The events were trumpeted in the PRC’s party-controlled press both internally and externally to show China’s leadership and generosity to domestic and international audiences.

This episode speaks to broader theories about images, narratives, and status in international relations (e.g. Allan, Vucetic, and Hopf Citation2018; Gunitsky Citation2017; Larson, Paul, and Wohlforth Citation2014). Non-democratic states in a global order that rhetorically privileges democracy and human rights make concerted efforts to influence the ways foreign audiences perceive them (Bush and Zetterberg Citation2021; Carter and Carter Citation2021; Dukalskis Citation2021; Gläßel, Scharpf, and Edwards CitationForthcoming; Mattingly and Sundquist Citation2023; Scharpf, Gläßel, and Edwards Citation2023). Image management strategies can help states achieve foreign policy goals and boost domestic prestige for the government by showing that the state is respected abroad (Dukalskis Citation2021; Holbig Citation2011). At a deeper level, such strategies can influence the terms on which international discourse takes place so that it reflects the state’s preferred frames and concepts (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle Citation2013). This can shape discussion in a more fundamental way than merely improving one’s image because it influences the standards by which behavior is normatively evaluated (see Bettiza and Lewis Citation2020; Owen Citation2010, 69).

Empirically, while it is no surprise that China’s party-controlled press presented an upbeat assessment of the PRC’s activities during the crisis, it is not clear if medical exchanges like the Serbian example influenced Beijing’s portrayal in media that it did not control. We evaluate this question on two levels. First, we use a research design that allows us to assess the impact of this kind of ‘mask diplomacy' on the tone with which China and Covid-19 were talked about in a country’s press during the initial crisis. We find that these efforts markedly improved the media tone regarding China after the first instances of mask diplomacy amid the pandemic’s initial stages in 2020.

Second, we investigate underlying discourse change by assessing differences in word usage before and after a country received mask diplomacy. We find that articles mention terms prioritized in China’s self-description of its Covid-19 policies much more in the week after having received support. Key formulations like ‘assistance', ‘commitment', ‘help', ‘solidarity', ‘fight', ‘support', and ‘prevention’ that are stressed in the PRC’s foreign-facing Covid-19 White Paper are among the frames the PRC wanted foreign audiences to use when discussing China’s pandemic approach. Mask diplomacy appears to have induced recipient country media to adopt China’s strategically preferred terms during the initial stages of the crisis. Taken together these findings suggest that not only were China’s mask diplomacy efforts successful in changing the overall tone describing its role in the pandemic, but they were even able to embed key terms associated with China’s specific narratives in the texts of foreign media.

These evaluations draw on data from a diverse range of sources. To construct our novel outcome measure of media tone, we apply a semi-supervised scaling method (Watanabe Citation2021; Zollinger Citation2024) to over 1.5 million English statements from online newspapers from 99 countries that mention China in the context of Covid-19. We then construct a novel measure of the first instance of mask diplomacy in 120 countries, drawing on a database of over 1,600 mask diplomacy records developed from a range of media and official sources. Our approaches to identifying causal effects of mask diplomacy utilize the temporal nature of our data to employ a multi-period difference-in-differences approach.

Our findings speak to several important questions. First, they help us understand the effects of a state’s image management efforts amid a deadly global crisis that emerged in that country. If China can mitigate its reputational damage in these difficult circumstances, then this shows that a negative image or stigma can be alleviated through concerted counter-effort (Adler-Nissen Citation2014). Second, they help us understand the effectiveness of China’s external propaganda and public diplomacy. PRC authorities have long wanted to change the international conversation about issues important to Beijing (Brady Citation2015; Nathan Citation2015). This research design allows us to measure its effectiveness on one of the biggest international news stories of the century thus far, and, in turn, builds on literature that tries to assess the outcomes of authoritarian propaganda and public diplomacy (Carter and Carter Citation2021; Dukalskis Citation2021; Gläßel, Scharpf, and Edwards CitationForthcoming), China’s efforts specifically (Gurol Citation2023; Marsh Citation2023; Mattingly et al. CitationForthcoming; Repnikova Citation2015; Van Dijk and Lo Citation2023; Wang Citation2023), and how China and its policies were portrayed globally during the pandemic (Fan and Zhang Citation2023; Li Citation2021). Third and finally, the findings advance studies of public diplomacy and image management that concentrate on attitudes toward the state in question, adding a focus on the underlying content that shapes how the state’s policies are presented and understood (Blair, Marty, and Roessler Citation2022; Goldsmith, Horiuchi, and Matush Citation2021).

International discourse, China, and the Covid-19 pandemic

This section elaborates a three-step argument in descending order of specificity. First, it establishes that states generally wish to be seen positively and take steps to shape their image among foreign audiences, at minimum by trying to avoid negative connotations. At a deeper level, states attempt to influence the terms of international discourse through strategic narratives, which can improve the state’s image by altering the reference points of discussion. Second, it shows how contemporary China, specifically, wishes to shape how the state is discussed. Third, it demonstrates that in the specific crisis of Covid-19, Beijing took an active approach to manage the narrative abroad both to avoid blame for the pandemic’s emergence and to be seen as a savior through its ‘mask diplomacy' efforts. Based on these arguments, it derives two hypotheses.

Image management and influencing discourse

States pay attention to how they are perceived abroad. Scholarship on soft power (Nye Citation1990), international status (Larson, Paul, and Wohlforth Citation2014), state branding (Van Ham Citation2002), state framing (Jourde Citation2007), strategic narratives (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle Citation2013), and state prestige (Fordham and Asal Citation2007) vary in their specific foci. Still, all emphasize a similar essential point: states care about and try to influence how foreign audiences regard them. Contemporary states are mindful not only about perceptions among elites, but also among foreign mass publics (Allan, Vucetic, and Hopf Citation2018; Blair, Marty, and Roessler Citation2022; Mattingly et al. Citation2013).

Having a positive image abroad is beneficial. It may help states be seen as a desirable destination for foreign investment, tourism, or international aid (e.g. Avraham Citation2015; Bush and Zetterberg Citation2021; Wells and Wint Citation1990). A positive reputation abroad can boost legitimacy at home by showing domestic audiences that the country is an attractive and respected model in the eyes of foreign publics (Holbig Citation2011). Being viewed positively can help states earn prestige, which can, in turn, help them amplify their preferred norms and values in the international system and thus exercise influence on issues important to them (Ambrosio Citation2010, 386; Fordham and Asal Citation2007, 33; Larson, Paul, and Wohlforth Citation2014, 19). Usually, states wish to avoid having a negative reputation and will often enact strategies to correct or address a perceived negative or ‘distorted’ portrayal (e.g. Adler-Nissen Citation2014; Kiseleva Citation2015, 322; Loh and Loke Citation2023; Wilson Citation2015, 294).

One mechanism through which a relatively more positive image can be achieved is by influencing the terms of reference about the state. States advance ‘strategic narratives' in which they represent themselves as well as events, systems, identities, and issues to their advantage (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle Citation2013; Roselle, Miskimmon, and O’Loughlin Citation2014). Strategic narratives are important because they can help shape the environment in which international interactions take place, thus potentially altering the assumptions and reference points used to assess a state’s image (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle Citation2013, 152). If the state can influence the narrative in this way and get other actors to speak on those terms, then a more positive international image is likely to result. Analyzing the projection of strategic narratives requires tracking their flow and spread throughout international discourse (Roselle, Miskimmon, and O’Loughlin Citation2014, 79), something we attempt to do below.

China, image, and discourse power

China is perhaps even more attuned to its external image and narratives about it than most states. PRC officials pay considerable attention to advancing preferred impressions of the country and countering negative ones (Brady Citation2015; Hartig Citation2016; Kurlantzick Citation2023; Tsai Citation2017). China’s external image crafting is done via two main bureaucratic channels: the propaganda apparatus and the foreign affairs system (Wang Citation2023). While internal and external propaganda and information efforts often feed one another (e.g. Edney Citation2014), internal and external imperatives sometimes clash (Wang Citation2023). For most of the post-Mao era, the main driver of China’s external image management efforts had to do with its desire to grow more powerful without being perceived as threatening to others (Brady Citation2015, 51; Zhao Citation2015, 195). In the Xi Jinping era (2012 – present), however, Deng Xiaoping’s famous dictum that China should bide its time and hide its brightness is arguably over (Doshi Citation2021). In an influential August 2013 speech at the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference, Xi instructed his audience to ‘tell China’s story well, disseminate China’s voice, and enhance its right to speak in the international arena' (quoted in Tsai Citation2017, 208). Perhaps nowhere is this assertive approach more obvious than in the PRC’s ‘Wolf Warrior' diplomacy that features aggressive and nationalistic responses to criticism by foreigners, especially when it comes from people in the West (Brazys, Dukalskis, and Müller Citation2023; Dai and Luqiu Citation2022; Sullivan and Wang Citation2023).

A key Chinese foreign policy concept when it comes to China’s image abroad is ‘discourse power', apparently first used officially in 2008 (Rolland Citation2020, 53; Zhao Citation2016). This concept is rooted in the idea that ‘China faces a hegemony of discourse' because ‘Western' media outlets and political ideas disproportionately influence international discourse, with the result that China is portrayed as not living up to that implied standard (Liu Citation2020, 280–283; Wang Citation2008, 265). This reflects a deeper belief of Xi Jinping and many in China’s leadership that the existing international system is biased against China (Tsang and Cheung Citation2024, 168). Enhancing China’s discourse power equates with improving Beijing’s ability to ‘speak’ or communicate internationally and compel others to listen (Rolland Citation2020, 7, 10–12; see also Zhao Citation2016). As a result, China has invested heavily in its external propaganda (Brady Citation2015; Tsai Citation2017; Kurlantzick Citation2023; Marsh Citation2023), spreads its messages to elite audiences (Hackenesch and Bader Citation2020), attempts to influence or co-opt foreign media outlets and journalistic unions (Kurlantzick Citation2023; Lindberg, Bradshaw, and Lim Citation2023), and has become more assertive in articulating its preferred concepts in international fora (Dukalskis Citation2023; Foot Citation2020; Fung Citation2020; Rolland Citation2020). Enhancing discourse power goes beyond broadcasting external propaganda and entails getting other actors to adopt China’s preferred frames of reference for understanding the country.

Two indicators of how successful a strategy of enhancing discourse power is for the PRC are (1) how positively or negatively the country is portrayed in international media, and (2) the terms on which China’s policies are discussed. While the PRC will of course be portrayed positively in China’s own external propaganda outlets, influencing coverage in outlets one does not control is an indication that Beijing’s emphasis on influencing international discourse is making headway. Below we investigate whether publicity surrounding the PRC’s mask diplomacy was able to do this.

The PRC, mask diplomacy, and Covid-19

Covid-19 and China’s relationship to it provide useful grounds to investigate arguments about image management, strategic narratives, and China’s discourse power. A transnational crisis can challenge a state’s ability to avoid reputational damage, particularly if questions of blame enter the picture (Loh and Loke Citation2023). A pandemic like Covid-19 is one such point of crisis. Pandemics have long been blamed on others or outsiders, often in racialized terms, a process Dionne and Turkmen (Citation2020) describe as ‘pandemic othering.' Research has mapped the contours of blame attribution for the spread of Covid-19, but clearly culpability for the pandemic has been a feature of international discourse since the disease’s outbreak (Flinders Citation2020; Jaworsky and Qiaoan Citation2021; Lin Citation2021; Loh and Loke Citation2023). Fan and Zhang (Citation2023), for example, find that media reporting in foreign countries about China in the early days of the pandemic was associated with the situation of the disease in that country.

The PRC, therefore, had unique incentives to manage its image and shape international discourse in the early days of Covid-19. The pandemic originated in Wuhan in late 2019. Information about the disease was initially suppressed, with local doctors and other citizens who sounded the alarm punished. In January 2020, the central government took control of the pandemic response and initiated a ‘prevention and control’ strategy, which entailed ‘an interweaving of public health with authoritarian tools of surveillance, policing, and securitization' (Greitens Citation2020, E171).

The government has sought to control information about its domestic response. Beijing is wary of welcoming investigative teams from the World Health Organization to examine the origins of the virus, erecting barriers to their access and the independence of their work (Hernandez Citation2021). An Associated Press investigative report based on leaked documents and interviews with Chinese scientists found that the government has been centralizing and controlling the release of scientific publications about the disease’s origins since at least March 2020 at the highest levels of the government, with dissenters facing punishment (Kang, Cheng, and McNeil Citation2020). The PRC features a sophisticated regime of domestic information control (e.g. Huang, Boranbay-Akan, and Huang Citation2019; Pan, Shao, and Xu Citation2022), and it has used that system to limit and shape information about its pandemic response.

In the resulting information void, Beijing has sought to build an image of success in overcoming the disease (Verma Citation2020, 253; Wen Citation2021). The contrast was often drawn directly with failures in the pandemic responses of the United States and Europe (Verma Citation2020, 253). China’s domestic Covid-19 successes have often been attributed to the ostensibly unique wisdom and leadership of Xi Jinping (Xinhua Citation2020b). This messaging mostly continued despite frustrations with China’s zero-Covid strategy involving prolonged and widespread lockdowns (see, e.g. Cao Citation2022) and a brief wave of protests about the strategy before it was lifted in December 2022. To avoid blame, the PRC mixed censorship of undesirable information with strategies of defensive, aggressive, and proactively benevolent rhetoric (Loh and Loke Citation2023).

With regard to the latter, the Chinese government touted both the wisdom of its Covid-19 model and its generosity abroad (Greitens Citation2020, EE174–E178; Brazys and Dukalskis Citation2020, 70). A June 2020 State Council White Paper stressed the success of China’s actions, its charity and cooperation abroad, its ostensible openness and transparency, and Xi Jinping’s personal leadership role in promoting international cooperation (Xinhua Citation2020a). China’s external propaganda streams regularly featured content with foreign political leaders thanking the PRC for its apparent generosity, with headlines like ‘Zimbabwean president thanks China for Covid-19 vaccine donation’ (CGTN Citation2021), ‘EU’s Von der Leyen thanks China for support including 2 million masks' (CGTN Citation2020b), and ‘Pakistani senate passes resolution to thank China for support in Covid-19 fight' (CGTN Citation2020c).

These efforts became colloquially known as ‘mask diplomacy', given the prevalent image of face masks as an everyday marker of the pandemic as well as China’s role as the main mask producer globally. These efforts can be seen as a form of more general ‘health diplomacy', which Fazal (Citation2020, E78) defines ‘as international aid or cooperation meant to promote health or that uses health programming to promote non-health-related foreign aims.' More will be explained below, but China’s provision of aid, equipment, expertise, training, and medical labor to other countries played a crucial role in its Covid-19 image crafting (on mask diplomacy in Latin America, see Telias and Urdinez Citation2022; on Central and Eastern Europe, see Kowalski Citation2021).

These three arguments, namely that states attempt to influence how they are perceived through advancing strategic narratives, that China is attuned to its image and discourse power, and that Covid-19 presented incentives for China to advance its image management efforts, lead to two main hypotheses. They address China’s preferred image and its preferred narrative content when it comes to Covid-19, respectively. Mask diplomacy provides useful markers to test the extent of China’s ability to advance its aims in these areas. Thus:

Hypothesis 1: PRC mask diplomacy changed the tone of media coverage in recipient countries to be more positive toward China.

Hypothesis 2: Media in recipient countries used China’s preferred terms to describe the PRC’s Covid-19 response more after receiving mask diplomacy.

Data, scaling, and validation

We employ quantitative text analysis to test our hypotheses. In this section, we describe the data collection procedure, provide summary statistics, outline the scaling approach, and validate the scaling results based on human coding, face validity checks, and cross-country comparisons.

Data

To establish our outcome measures, we build a novel text corpus of online newspaper articles to test how the media portrayed China during the first year of the pandemic. More specifically, we retrieve the URLs for all articles in the Google ‘Big Query’ GDELTFootnote1 database that mention China and Covid-19 between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020. We retrieve the headings and full texts of all these articles.Footnote2 Some websites do not allow content retrieval, are blocked for certain IPs, or do not contain standard html fields to access the full text. We identify the language of an article using Google’s Compact Language Detector (Ooms Citation2021), a neural network model for language identification.

In the next step, we only keep websites that published at least 50 articles relating to Covid-19 and China in 2020. We add this filter to focus on legitimate news outlets and avoid results driven by websites that did not cover the topic of interest throughout the year. We then classify the country of a website. The initial classification relies on the ending of a domain. We hand-coded the country of origin for all websites that could not be classified unambiguously, either because the domain ending does not match with a country or because the domain ending is general (e.g. .com or .org). We visit the website and look up contact information to identify the country of the news outlet. Domains that could not be matched with a specific country are excluded from the empirical analysis.

We next extract the terms ‘china*’ or ‘chinese*’ in each article and keep the terms and their context of ±30 words using the quanteda R package (Benoit et al. Citation2018). We further limit this subset of statements by keeping only statements that also include at least one of the following terms as a regular expression: ‘*covid*’, ‘*corona*’, ‘*virus*’, ‘*disease*’, and ‘*pandemic*’. All terms are identified as regular expressions, and the query detects terms spelled in lower case, upper case, or title case.Footnote3

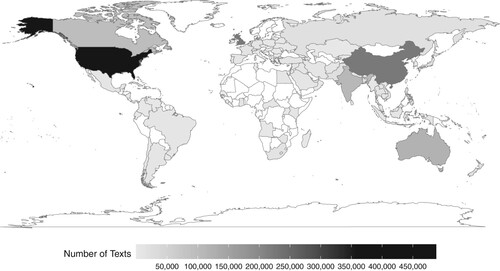

Based on these strict filters, statements in our limited corpus mention China and contain an unambiguous reference to the global pandemic. visualizes the geographical distribution of available and relevant English statements. Overall, the English text corpus considered in the difference-in-difference analysis includes 1,536,013 statements published on 1,583 domains from 100 countries.Footnote4

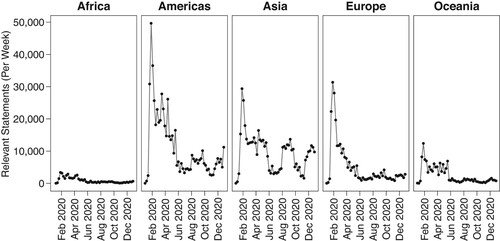

plots the weekly number of statements by continent from 1 January until 31 December 2020 to illustrate variation over time. Most articles come from websites published in the Americas, followed by European and Asian domains. The plot also underscores that most articles were published in the first half of 2020. This pattern is reasonable since the global outbreak of the pandemic, the potential blaming of China as the culprit, and China’s ‘mask diplomacy' efforts took place largely between January and June 2020. Notably, this window focuses on the initial stages of the pandemic, where China’s mask diplomacy efforts were most salient, and there is sufficient temporal variation in states that received mask diplomacy. Also, these treatments occur almost exclusively before any roll-out of the Chinese Covid-19 vaccines, given that formal deliveries did not begin until December 2020.Footnote5

As mentioned below, we remove Chinese party-state media from our analysis to analyze non-PRC sources for our models. However, this leaves two potential problems in our data. First, Xinhua is sometimes used as a wire service akin to the Associated Press or Reuters, meaning that PRC media may appear in independent non-PRC outlets. However, running (or not) a Xinhua article is a choice by the editor, suggesting that decisions about coverage pertaining to China are still being made independently. If mask diplomacy or other Chinese health diplomacy efforts induce more selection of Xinhua copy by independent editors abroad, then this is a choice that is consistent with our theoretical story. Second, some PRC media entities have purchased stakes in independent foreign outlets. This means that our analysis may be in danger of picking up inauthentic amplification of PRC propaganda instead of independent coverage or editorial choices. Most of these outlets are in the Chinese-language diaspora media (Tsai Citation2017, 207), which our analysis would not include, so this largely alleviates this concern. Still, there are reports of PRC ownership of non-Chinese language outlets (Cook Citation2020), often with ownership intentionally obfuscated through layers of go-between entities (Qing and Shiffman Citation2022). Without a comprehensive list of these arrangements it is difficult to account for this, but we doubt that the practice is widespread or systematic enough to skew our analysis.

Scaling method

One could consider two approaches to retrieve media tone about China from the texts. The first approach would rely on supervised machine learning. In this approach, human coders label a large corpus of sentences regarding the text’s framing of China. While this approach offers flexibility and a straightforward interpretation of the dependent variable, statements in news articles are not necessarily categorical. Instead, we expect that statements frame China on a continuous scale ranging from very negative to very positive. Sentiment dictionaries, a potential alternative, are often domain-specific, ignore terms that do not appear in the list of keywords, and do not necessarily capture the dimension of interest (for a discussion of advantages and shortcomings of dictionaries, see Benoit Citation2020; Watanabe Citation2021). Therefore, we opt for a semi-supervised scaling method, Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS). LSS positions documents on a pre-defined continuous scale (Brazys, Dukalskis, and Müller Citation2023; Watanabe Citation2021; Zollinger Citation2024). The LSS method requires the identification of a relatively small set of keywords that capture the underlying concept (so-called ‘seed words'). These seed words describe both ends of a unidimensional scale. The LSS algorithm estimates the semantic proximity based on cosine similarity scores between the pre-selected seed words and all other terms in the text corpus.Footnote6 Having estimated polarity scores for all words in the text corpus, LSS allows us to retrieve a word score for each term in the corpus and predict scores for each text in the corpus.

We assign words like spread*, origin*, cover*, silence*, and fraud* to the ‘negative' end of the scale, while terms such as help*, friend*, solidarit*, and donate* are assigned as seed words for the ‘positive' end of our unidimensional scale (for a list of all terms see Table A1). We train the LSS algorithm using seed words for our scale and apply the trained LSS algorithm to the entire text corpus, resulting in a score for each statement.

Validation

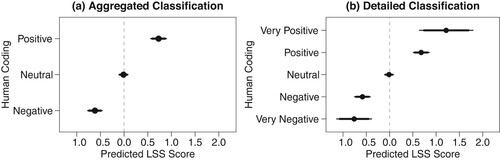

We validate the scaling results extensively, following best practices in text-as-data approaches. First, we extracted a random sample of 500 sentences. An instructed coder read these sentences (without having any information on the LSS scores for each text) and coded them on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means that China is portrayed very negatively, as a ‘culprit', while 5 implies a very positive portrayal of China, as a ‘savior'. Conceptually, our media tone scoring provides a continuous ‘culprit-savior' scale, where more positive scores imply language that is comparatively more ‘savior'-like (and vice-versa). We report the exact coding instructions in Section B of the Supporting Information (SI). We compare the human coding with the scaling results by running a linear regression with the continuous scaling score as the dependent variable and the human classification as the independent variable. plots the fitted values of the continuous scores for each category. We observe a high correspondence between both measures. Very negative mentions have the lowest scores, followed by negative and neutral mentions. Positive and very positive statements about China tend to have the highest scores.

Figure 3. Predicting media tone based on the human coding of the same set of statements. Note: The plots report predicted values of media tone conditional on the human classification of a statement. Error bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals.

Second, we report the 30 most negative statements (observations with the lowest values) and the 30 most positive statements (highest values) in Table A3. The scaling approach differentiates between negative and positive mentions. The examples below underscore that the selection of seed words in combination with the LSS method provides intuitive and interpretable scaling results.

Very negative score: ‘ … China deliberately suppressed or destroyed evidence of the coronavirus outbreak in an ‘assault on international transparency’ that cost tens of thousands of lives, according to a dossier … '

Very positive score: ‘face of COVID-19, China and Africa have offered mutual support, fought shoulder to shoulder with each other, and enhanced solidarity and strengthened friendship and mutual trust. China shall always remember the invaluable support Africa gave us at the height of our battle with the coronavirus. Over 50 African leaders have expressed solidarity and support in phone … ’

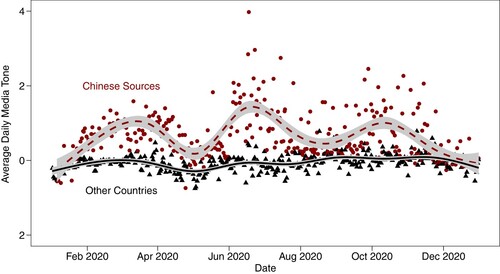

Figure 4. Comparing media tone in Chinese sources and all other sources. Note: Points indicate the daily media tone in Chinese sources (circles) and sources from other countries (triangles). Lines are generalized additive models with integrated smoothness.

As a final validation measure, we map our scoring onto Covid-19 ‘death peaks' in each country. Full details can be found in SI Section C, but briefly, using weekly data on Covid-19 related deaths, we evaluate if tone towards China is more negative during the peak weekly Covid-19 deaths in each country, and indeed that is what we find. We take this as further validation that our measure accurately captures sentiment towards China and Covid-19 in foreign media.

Having validated the scaling model and classified every relevant statement, we aggregate the scores to the level of country-week observations. More specifically, we estimate the mean scores of all articles published in a country in a given week. This gives us a panel of country-week mean scores. We then create a country-standardized measure of the LSS score discussed above where the mean score, by country, is 0 with a standard deviation of 1. This is our principal outcome measure for hypothesis 1. This standardization better enables us to make cross-country comparisons by helping to account for country-specific unobservable factors that may affect the ‘latent’ China LSS score. It also allows us to mitigate the differences in variance due to variation in the number of articles by country (where countries with fewer articles are likely to have higher variance in their LSS scores). Moreover, the standardization considers differences in the ideological positions of newspapers across countries. The selection of outlets relies on the domains available in the URL database. Our sample includes ideologically moderate and extreme domains. The standardization across countries takes this heterogeneity into account and allows us to test how media tone changes within a certain country, using the average tone as the baseline.

To construct our primary explanatory variable, the mask diplomacy ‘treatment', we create a novel dataset of individual mask diplomacy events at a country-week level. The PRC has a long history of providing health-related financial assistance and quickly responded to the Covid-19 pandemic (Morgan and Zheng Citation2019a; Citation2019b). To gather this data, we used both media and official sources, including the Chinese International Development Cooperation Agency’s (CIDCA’s) official press releases in Mandarin and English, to identify over 1,600 mask diplomacy events across 168 countries. We then use that data to code a treatment binary variable in the first week a country received some form of Chinese mask diplomacy. Additional details on the coding methodology as well as descriptive statistics and graphs can be found in SI Sections G and H.

Identification approach

We use this data to conduct a multi-period difference-in-differences analysis with variation in treatment timing following Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021) who show the equivalence of that approach to a classic two-period difference-in-differences average treatment effect of the treated (ATT). As discussed above, the treatment is an indicator variable in the week of the first instance of media reporting of mask diplomacy in a country. As nearly all countries in our sample eventually receive mask diplomacy, we use countries who are ‘not-yet-treated' at the time a given country is treated as our comparator group. We adopt an unconditional parallel trends assumption as we have insufficient variation on the pre-treatment covariates for which we have weekly data, namely Covid-19 cases or deaths.Footnote7 However, as shown in the results below, the unconditional parallel trends assumption appears to hold in any case. As discussed by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021, 206) the major drawback of using the ‘not-yet-treated' comparison group is that parallel trends may evolve differently in ‘early' and ‘late' periods. As they note, it is important to consider the context when considering the parallel trends assumption. In this case, we do expect parallel trends to hold in ‘late' periods only as we expect to see a treatment response to mask diplomacy once (news about) the pandemic took hold globally in late February and March 2020, which was relatively close to the first instances of mask diplomacy in many countries. Accordingly, we think this comparator group is appropriate.

Our analysis spans the first six months (26 weeks) of 2020 (through June), as by this week, all but one country in our sample had received mask diplomacy (Table A7). We can match sufficient media data with mask diplomacy data for 98 countries and territories. The resulting panel is unbalanced as we do not have media score observations for all countries in all weeks because China may not have been mentioned in relation to Covid-19 in the media of all countries in all weeks. We account for this in our modeling. In the results below, we calculate both aggregate ATTs and plot dynamic treatment effects which, as discussed further by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021), are comparable to an event-study type approach. In essence, this allows us to evaluate if mask diplomacy generated a longer-lasting boost in media tone regarding China over several weeks, effectively ‘changing the course' of the Covid-19 narrative about China, or if the effect was more ephemeral and limited to the initial delivery of the assistance.

In the main models, we assume that the media did not have any advance indication of when China would provide mask diplomacy, or if they did, they would publish that information immediately. Indeed, a handful of our observations come from media reports indicating a future delivery of mask diplomacy. Thus, any anticipation of the actual event by the media is captured in the treatment data itself, which is based on the date of the first media mention of the mask diplomacy event.

We also recognize the fact that it is likely that the media coverage of the mask diplomacy events themselves may be responsible for more positive tone. This is not necessarily problematic to our investigation because part of the PRC strategy in using mask diplomacy is to generate positive stories about mask diplomacy. However, as a ‘hard test' for our hypotheses, we also consider models where we remove any mask diplomacy text from the computation of the tone score to see if mask diplomacy efforts influence the media narrative in stories about China and Covid-19 that do not mention mask diplomacy itself.Footnote8

Results

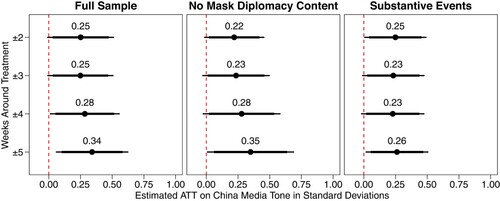

considers the aggregate ATT using different windows around the treatment. A window of ±2 means we assess the treatment effect two weeks before and two weeks after the treatment. We estimate the aggregated differences for windows ranging from ±2 weeks to ±5 weeks. The left-hand panel reports results for the full sample of texts. The panel in the middle limits the content to mentions of China and Covid-19 that exclude mask diplomacy content. The right-hand panel uses only ‘substantive events' as a measure of mask diplomacy (excluding events such as online medical consultations). We observe a positive and sizeable effect in all three scenarios and for the time windows between ±2 and ±5 weeks. For instance, in the full sample the treatment effects of receiving mask diplomacy correspond to a more positive coverage of China of around 0.25–0.34 standard deviations. When focusing on coverage that does not comment on mask diplomacy itself, the effects remain positive and statistically significant, and the effect size even increases slightly. Using substantive events only does not change the conclusions. In sum, the effect size is quite stable when using alternative treatment windows, measures of media content, and mask diplomacy events.

Figure 5. Overall aggregate ATT of receiving mask diplomacy support on media tone, for a window of ±2 to ±5 weeks around the treatment. Note: Horizontal error bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals.

Overall, we take these results as clearly supporting hypothesis 1. Examples from our sample illustrate what our observed shift in media tone associated with mask diplomacy looks like in practice. Using scores from Canadian media, we see that samples at the standardized mean (0.00) of all Canadian articles about China and Covid-19 are not particularly positive, with some straightforward descriptions of the unfolding of the pandemic’s origins in China:

The World Health Organization declared on Thursday that the coronavirus epidemic in China now constitutes a public health emergency of international concern. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, announced the decision after a meeting of its Emergency Committee, an independent … . (standardized LSS score of 0.063)

Videos showing residents at the centre of China's coronavirus epidemic haranguing a top Chinese official have highlighted persistent anger at how authorities have handled the crisis. The clips, which have been circulating online since Thursday … . (standardized LSS score of 0.077)

the strategy to contain the disease – identifying people with infections and rapidly isolating them – was still the best approach, and had shown positive effects in China, South Korea and Singapore. (standardized LSS score of 0.31)

… divert attention to its renewed efforts to slow the coronavirus pandemic, with Xi announcing the $2 billion outlay over two years to fight it … . (standardized LSS score of 0.4)

As a robustness test, we extend the text corpus by collecting and machine translating statements from over 80 languages into English. We matched 240,000 of these statements with a country based on the domain ending or manual coding. These texts increase the coverage from 99 to 120 countries. While the standard errors increase and some coefficients fail to reach statistical significance at conventional levels, the direction remains the same. Effect sizes are mostly comparable to the English corpus. SI Section E describes the procedure, results, and potential issues of this additional analysis.

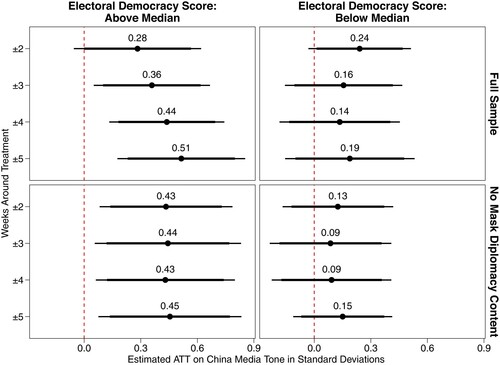

Finally, as an extension, we conduct subgroup inquiries that restrict our analyses to more and less democratic nations based on countries above or below the median 2019 V-Dem Electoral Democracy score (Coppedge et al. Citation2023). As seen in , we observe a pronounced positive effect in more democratic nations, which grows larger over time. In contrast, in less democratic countries, while still observing positive effects, these fail to reach standard thresholds of statistical significance. While this discrepancy may, in part, follow from the fact that it may be likely that there are more English-language sources in democracies, it could also be reflective of media tone in democracies being more malleable whereas in autocracies censorship breeds more conformity.

Figure 6. Subgroup Inquiry: Tone Changes in Countries Above/Below Median V-Dem Electoral Democracy Score. Note: Horizontal error bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals.

We believe that our results constitute conservative estimates of the relationship between mask diplomacy and media tone. While we have carefully checked the classification of countries based on domains and manual coding, validated the scaling method, extracted news articles based on several keywords, and identified ‘mask diplomacy' by reading hundreds of news articles, these data and measures might suffer from measurement bias.

First, using domain endings and manual assessments of websites for identifying the country of origin might result in some misclassification. Thus, a fraction of news articles will be allocated to the wrong countries. Second, the LSS method can approximate media tone, but not every statement aligns with human coding. Third, identifying mask diplomacy relies on news reports. We assess the first mention of Chinese support, which may not necessarily have been the most impactful. Despite these sources of potentially non-systematic measurement error, we find strong and consistent support for hypothesis 1: media tone improved significantly after a country received ‘mask diplomacy' from China.

Influencing the substance of the narrative

We now turn to hypothesis 2, moving beyond positive/negative tone to measure whether mask diplomacy was able to change the substance of news about China and Covid-19. Recall that ‘strategic narratives' are those in which the state represents itself and its role in events in its preferred ways. The pioneers of this approach recommend that understanding the projection of strategic narratives requires tracking their spread throughout international discourse (Roselle, Miskimmon, and O’Loughlin Citation2014, 79).

To identify the PRC’s preferred narrative terms about Covid-19, we turn to China’s June 2020 official White Paper on the topic, Fighting Covid-19: China in Action.Footnote9 White Papers (WPs) are official documents issued by the State Council Information Office (SCIO) that summarize and explain China’s policies, preferences, and formulations to external audiences. WPs can be taken as an aggregate of the official perspective and the PRC’s preferred narrative on a given topic. They are typically produced in English, thus indicating an external target audience, and they are usually widely publicized by PRC external media streams. In China’s political system, the SCIO is overseen by the party’s Propaganda Department, and SCIO itself describes its function as ‘to propel domestic media further along the path of introducing China to the international community, including China’s domestic and foreign policies.'Footnote10

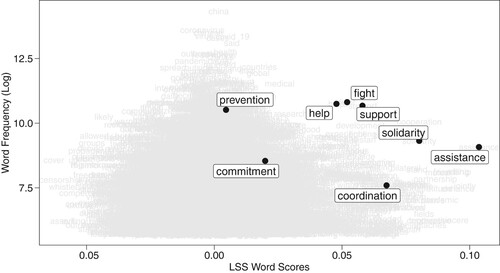

The Covid-19 WP can thus be taken as a reasonable approximation of the story the PRC wishes to tell about its relationship to Covid-19. To extract key terms underpinning the WP’s narrative, we first conducted a word frequency analysis of the WP. Based on that, we extracted terms that were central to the paper’s narrative. The resulting key narrative terms included ‘prevention', ‘fight', ‘help', ‘assistance', ‘support', ‘coordination', ‘commitment', ‘guide', and ‘solidarity’. shows the distribution of LSS scores, along with key terms. These key narrative terms have high word frequencies and positive LSS scores. Our approach permits a straightforward inquiry do key terms from the white paper appear more frequently in news articles following a country’s receipt of mask diplomacy? Although word embeddings (Mikolov et al. Citation2013) could be an appropriate alternative for detecting text similarity and narratives, we chose a simpler and more easily interpretable method.

Figure 7. LSS scores and logged word frequencies. Note: The points and boxes show the word scores of the key terms identified in the white paper. The grey labels show the scores of words that appear at least 300 times in our corpus of statements mentioning China and Covid-19.

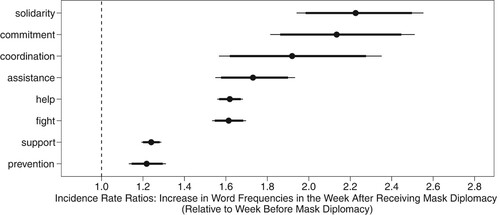

To identify the diffusion of preferred PRC terms in the international media, we select all full texts of English articles published in the week before, the week of, and the week after the mask diplomacy treatment in each country. This sample consists of 35,198 newspaper articles, with each mentioning China and the pandemic. We count how often the key terms appear in each newspaper article and store the counts of each word in each article. Afterwards, we run a negative binomial regression with the count of a word in each article as the dependent variable and the timing (before, during, after mask diplomacy) as the main independent variable. We add country fixed effects for each regression model. Following Chang et al. (Citation2022), we estimate incidence rate ratios from negative binomial regression models for each word. More specifically, we show the relative ratio of word usage increases or decreases in the week after a country received mask diplomacy, relative to the week before the mask diplomacy treatment. A value of 1.3 implies that word usage increased by 30%, a value of 2 means that the word count increased by 100%. shows that terms such as ‘solidarity’ and ‘commitment’ have more than doubled. The words ‘coordination’, ‘assistance’, ‘help’, and ‘fight’ are used over 50% more often after the country received support from China, while ‘support’ and ‘prevention’ also increased by around 20%.

Figure 8. Incidence rate ratios showing the relative ratio of word usage increases after a country received mask diplomacy, relative to the week before the mask diplomacy support. Note: Results based on separate negative binomial regressions for each word. Horizontal bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals. Regression coefficients are reported in Table A6.

These results suggest that a key mechanism driving the PRC’s more positive image in a country after the provision of mask diplomacy had to do with the changing underlying narrative about China and Covid-19. Key terms that the PRC prefers like ‘assistance’, ‘support’, ‘fight’, and ‘solidarity’ became markedly more common in a country’s press during and after its initial receipt of mask diplomacy. This indicates that the PRC was able to change the underlying discussion about China and Covid-19, which is powerful because it alters the standards and terms of reference in international discussion so that the state fares better.

Discussion and conclusion

Our results show that Beijing’s mask diplomacy worked to offset reputational damage from the Covid-19 pandemic and to change the international conversation about the PRC and Covid-19 in the initial phases of the pandemic. High-profile exchanges or donations of medical equipment or expertise with a country helped boost the PRC’s portrayal in that country as measured by how it was talked about in the press as related to Covid-19. Importantly, these effects were not just driven by positive coverage about the mask diplomacy itself, but also extended to coverage about China and Covid-19 that was not directly about mask diplomacy.

It appears that Beijing’s health diplomacy charm offensive worked, although it is important to stress that we cannot measure long-term effects nor the impact of this coverage on public opinion. Furthermore, our main sample is only in English, which means that it measures a limited slice of the global media. However, given that Beijing is most concerned with competing with the agenda-setting powers of US and UK global media, we maintain this is an important sample. It may not be generalizable to all languages (and results are somewhat weaker when adding machine-translated articles), but existing research does suggest that the PRC is working to influence media and its institutions the world over (Kurlantzick Citation2023; Lindberg, Bradshaw, and Lim Citation2023). Ultimately, while observers sometimes dismiss China’s external outreach as clumsy and unable to influence proceedings in media outlets it does not control, these results suggest that those assumptions should be questioned. Not only did the PRC’s portrayal improve, but the terms in which it was discussed changed.

Theoretically, these results build our knowledge about international image management and associated concepts. Faced with an image crisis of global proportions, China’s political system adopted a multipronged strategy of controlling domestic information, amplifying its preferred messages, challenging critics, and getting foreign ‘friends' of the PRC like Vučić to speak positively about its Covid-19 response. These efforts could not completely avert damage to China’s image stemming from the pandemic, but when combined with mask diplomacy, they were effective during a crisis. It is difficult to spin a positive image out of nothing; success or generosity gives material to work with. Scholars of ideas and reputations in international relations have long examined the nexus between material and normative power; this research speaks to that tradition.

Beyond the case of China and Covid-19, these results suggest that external image management can change the way states are portrayed for foreign audiences and the terms on which they are discussed. It adds to a growing body of literature, particularly about the external propaganda and image management strategies of authoritarian states being able to change global discourse (Bush and Zetterberg Citation2021; Dukalskis Citation2021; Gurol Citation2023; Mattingly et al. Citation2013; Scharpf, Gläßel, and Edwards Citation2023). In an age of unraveling liberal international order, this finding has serious implications as authoritarian states promote counter-norms to the existing system (Cooley and Nexon Citation2020, 95). The results suggest that authoritarian states have methods available to them to influence collective understandings of international issues at a deeper level than previously thought. While influencing public opinion or disposition toward a state is already important, influencing how independent actors present concepts and issues has the potential to yield longer-term impacts.

Finally, future research may consider several avenues. Researchers may wish to combine results like this that rely on media sentiment analysis with surveys (De Vries et al. Citation2021) and discussions on social media (Cirone and Hobbs Citation2023; Lu, Pan, and Xu Citation2021) to understand how these positive impressions translate, if at all, to public opinion. Further, the temporal scope may be extended to explore the effects of crisis-induced image management over a longer period. It may also be worthwhile to consider China’s portrayal amid the Covid-19 pandemic in a dynamic relationship with its main international rival, the United States.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.7 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the four anonymous reviewers and participants at conferences, workshops, and seminars at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study, the Swedish National China Centre, the School of International Relations and Public Affairs (SIRPA) at Fudan University, the University College Dublin (UCD) Energy Institute, and the UCD College of Social Sciences and Law Covid-19 Showcase for comments and suggestions. In addition, we would like to thank Juno Ellison, Junhyoung Lee, Robin Rauner, Aubrey Saunders, Carl Smith, and Feiyang Xu for outstanding research assistance. Hauke Licht and Maël Kubli provided helpful advice on the retrieval and translation of news articles. Brian Burgess, Samantha Custer, Carrie Dolan, Emilie Efronson, Sid Ghose, Pippa Morgan, and Yu Zheng all contributed to developing the ‘mask diplomacy’ coding method. We are very grateful to Pippa Morgan for assistance in collecting ‘mask diplomacy’ information from the CIDCA website.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data and R scripts required to verify the reproducibility of the results in this article are available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KRXMXJ.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 While the GDELT database has been critiqued for the accuracy of its event data (Hammond and Weidmann Citation2014), we do not use this data or the GDELT tone data, but instead only utilize it as an aggregation of URLs for articles which contain our keyword terms.

2 We developed a scraper that loads each URL, checks whether the page exists, asks for permission to scrape using the polite R package (Perepolkin Citation2019), and saves the title and body of the news article.

3 A human coder manually annotated 200 statements containing the term *virus* (identified as a regular expression) to assess whether these statements related to Covid-19, another infectious disease, or potentially a computer virus. 199 of these 200 statements related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

4 The difference-in-differences regression models consider 99 countries. China is not considered in this analysis we assess media tone in countries that could receive mask diplomacy support from China.

5 See https://bridgebeijing.com/our-publications/our-publications-1/china-covid-19-vaccines-tracker/#Total_and_Weekly_Tracker_Highlights (Accessed 9 January 2024).

6 We follow the approach described extensively in Watanabe (Citation2021).

7 Notably, while deaths are likely to be a confounder for mask diplomacy and media tone, they are also likely to be endogenous with mask diplomacy, as the mask diplomacy supplies will reduce deaths. Beyond this, there is very little variation in the pre-treatment deaths data (as we have, in most instances, only a few weeks of non-zero deaths prior to treatment). Accordingly, we do not introduce controls for deaths as this may result in post-treatment bias but instead adopt the unconditional parallel trends assumption. Ideally, one might address this issue using an instrument for the mask diplomacy events, but we are unaware of any that would meet the conditions for suitability.

8 To conduct this analysis, we identify and remove mask diplomacy articles from our main corpus. To stack the deck against finding effects, we opt for a restrictive approach and exclude all statements that mention one of over 60 terms or multi-word expressions that could potentially describe PRC mask diplomacy. The most frequent terms include ‘vaccine*’, ‘mask*’, ‘respirator*’, ‘test*’, ‘medical supply*’, ‘donate’, and ‘Chinese doctors’. All these terms clearly could relate to China supporting other countries. To test whether the media tone also changed when ignoring texts about China’s support, we remove all text segments that mention one or more of these terms (around 15% of all statements). Afterwards, we aggregate the media tone to the levels of country-weeks.

9 Full text available here: https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202006/07/content_WS5edc559ac6d066592a449030.html (Accessed 9 January 2024).

10 See ‘About SCIO’ here: http://english.scio.gov.cn/aboutscio/index.htm (Accessed 9 January 2024).

References

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2014. “Stigma Management in International Relations: Transgressive Identities, Norms, and Order in International Society.” International Organization 68 (1): 143–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000337.

- Allan, B. B., S. Vucetic, and T. Hopf. 2018. “The Distribution of Identity and the Future of International Order: China’s Hegemonic Prospects.” International Organization 72 (4): 839–869. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818318000267.

- Ambrosio, T. 2010. “Constructing a Framework of Authoritarian Diffusion: Concepts, Dynamics, and Future Research.” International Studies Perspectives 11 (4): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00411.x.

- Avraham, E. 2015. “Destination Image Repair During Crisis: Attracting Tourism During the Arab Spring Uprisings.” Tourism Management 47: 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.003.

- Benoit, K. 2020. “Text as Data: An Overview.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Political Science and International Relations, edited by L. Curini and R. Franzese, 461–497. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Benoit, K. K. W., H. Wang, P. Nulty, A. Obeng, S. Müller, and A. Matsuo. 2018. “quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data.” Journal of Open Source Software 3 (30): 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Bettiza, G., and D. Lewis. 2020. “Authoritarian Powers and Norm Contestation in the Liberal International Order: Theorizing the Power Politics of Ideas and Identity.” Journal of Global Security Studies 5 (4): 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz075.

- Blair, R. A., R. Marty, and P. Roessler. 2022. “Foreign Aid and Soft Power: Great Power Competition in Africa in the Early Twenty-First Century.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (3): 1355–1376. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000193.

- Brady, A.-M. 2015. “Authoritarianism Goes Global (II): China’s Foreign Propaganda Machine.” Journal of Democracy 26 (4): 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0056.

- Brazys, S., and A. Dukalskis. 2020. “China’s Message Machine.” Journal of Democracy 31 (4): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0055.

- Brazys, S., A. Dukalskis, and S. Müller. 2023. “Leader of the Pack? Changes in ‘Wolf Warrior Diplomacy’ After a Politburo Collective Study Session.” The China Quarterly 254: 484–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741022001722.

- Bush, S. S., and P. Zetterberg. 2021. “Gender Quotas and International Reputation.” American Journal of Political Science 65 (2): 326–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12557.

- Callaway, B., and P. H. C. Sant’Anna. 2021. “Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.

- Cao, D. 2022. “Xi: Dynamic Zero-COVID Policy Works”. Xinhua, June 30, 2022. Accessed January 9, 2024. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202206/30/WS62bcd80ea310fd2b29e6962b.html.

- Carter, E. B., and B. L. Carter. 2021. “Questioning More: RT, Outward-Facing Propaganda, and the Post-West World Order.” Security Studies 30 (1): 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885730.

- CGTN. 2020b. “EU’s Von der Leyen Thanks China for Support Including 2 Million Masks.” China Global Television, March 19, 2020. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-03-19/EU-s-Von-der-Leyen-thanks-China-for-support-including-2-million-masks-OYfKbN0vS0/index.html.

- CGTN. 2020c. “Pakistani Senate Passes Resolution to Thank China for Support in COVID-19 Fight.” China Global Television, May 14, 2020. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-05-14/Pakistani-senate-passes-resolution-to-thank-China-for-COVID-19-support-QuBQbUDfQ4/index.html.

- CGTN. 2021. “Zimbabwean President Thanks China for COVID-19 Vaccine Donation.” China Global Television, February 5, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-02-05/Zimbabwean-president-thanks-China-for-COVID-19-vaccine-donation–XDgHwoTMJi/index.html (accessed 9 January 2024).

- Chang, K.-C., W. R. Hobbs, M. E. Roberts, and Z. C. Steinert-Threlkeld. 2022. “Covid-19 Increased Censorship Circumvention and Access to Sensitive Topics in China.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (4): e2102818119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102818119.

- Cirone, A., and W. Hobbs. 2023. “Asymmetric Flooding as a Tool for Foreign Influence on Social Media.” Political Science Research and Methods 11 (1): 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.9.

- Cook, S. 2020. Beijing’s Global Megaphone. Washington, DC: Freedom House. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/beijings-global-megaphone.

- Cooley, A., and D. Nexon. 2020. Exit from Hegemony: The Unravelling of the American Global Order. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, J. Teorell, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, et al. 2023. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

- Dai, Y., and L. R. Luqiu. 2022. “Wolf Warriors and Diplomacy in the New Era: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Diplomatic Language.” China Review 22 (2): 253–283. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48671506.

- De Vries, C., B. N. Bakker, S. B. Hobolt, and K. Arceneaux. 2021. “Crisis Signaling: How Italy’s Coronavirus Lockdown Affected Incumbent Support in Other European Countries.” Political Science Research and Methods 9 (3): 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.6.

- Dionne, K. Y., and F. F. Turkmen. 2020. “The Politics of Pandemic Othering: Putting COVID-19 in Global and Historical Context.” International Organization 74 (S1): E213–E230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000405.

- Doshi, R. 2021. The Long Game: China’s Strategy to Displace American Order. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dukalskis, A. 2021. Making the World Safe for Dictatorship. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dukalskis, A. 2023. “A Fox in the Henhouse: China, Normative Change, and the UN Human Rights Council.” Journal of Human Rights 22 (3): 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2023.2193971.

- Edney, K. 2014. The Globalization of Chinese Propaganda: International Power and Domestic Cohesion. New York: Palgrave.

- Fan, X., and Y. Zhang. 2023. “‘Just a Virus’ or Politicized Virus? Global Media Reporting of China on COVID-19.” Chinese Sociological Review 55 (1): 38–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2022.2116308.

- Fazal, T. M. 2020. “Health Diplomacy in Pandemical Times.” International Organization 74 (S1): E78–E97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000326.

- Flinders, M. 2020. “Gotcha! Coronavirus, Crises and the Politics of Blame Games.” Political Insight 11 (2): 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041905820933371.

- Foot, R. 2020. China, the UN, and Human Protection: Beliefs, Power, Image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fordham, B. O., and V. Asal. 2007. “Billiard Balls or Snowflakes? Major Power Prestige and the International Diffusion of Institutions and Practices.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (1): 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00438.x.

- Fuchs, A., L. C. Kaplan, K. Kis-Katos, S. Schmidt, F. Turbanisch, and F. Wang. 2021. “Mask Wars: China’s Exports of Medical Goods in Times of COVID-19.” AidData Working Paper 108. https://www.aiddata.org/publications/mask-wars-chinas-exports-of-medical-goods-in-times-of-covid-19.

- Fung, C. 2020. “Rhetorical Adaptation, Normative Resistance and International Order-Making: China’s Advancement of the Responsibility to Protect.” Cooperation and Conflict 55 (2): 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836719858118.

- Gläßel, C., A. Scharpf, and P. Edwards. Forthcoming. “Does Sportswashing Work? First Insights from the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.” The Journal of Politics.

- Goldsmith, B. E., Y. Horiuchi, and K. Matush. 2021. “Does Public Diplomacy Sway Foreign Public Opinion? Identifying the Effect of High-Level Visits.” American Political Science Review 115 (4): 1342–1357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000393.

- Greitens, S. C. 2020. “Surveillance, Security, and Liberal Democracy in the Post-COVID World.” International Organization 74(S1): E169–E190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000417.

- Gunitsky, S. 2017. Aftershocks: Great Powers and Domestic Reforms in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gurol, J. 2023. “The Authoritarian Narrator: China’s Power Projection and its Reception in the Gulf.” International Affairs 99 (2): 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiac266.

- Hackenesch, C., and J. Bader. 2020. “The Struggle for Minds and Influence: The Chinese Communist Party’s Global Outreach.” International Studies Quarterly 3(3): 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa028.

- Hammond, J., and N. B. Weidmann. 2014. Using Machine-Coded Event Data for the Micro-Level Study of Political Violence.” Research and Politics 1 (2): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168014539924.

- Hartig, F. 2016. “How China Understands Public Diplomacy: The Importance of National Image for National Interests.” International Studies Review 18 (4): 655–680. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viw007.

- Hernandez, J. C. 2021. “Two Members of W.H.O. Team on Trail of Virus Are Denied Entry to China.” New York Times, January 13, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/world/asia/china-who-wuhan-covid.html.

- Holbig, H. 2011. “International Dimensions of Legitimacy: Reflections on Western Theories and the Chinese Experience.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 16 (2): 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-011-9142-6.

- Huang, H., S. Boranbay-Akan, and L. Huang. 2019. “Media, Protest Diffusion, and Authoritarian Resilience.” Political Science Research and Methods 7 (1): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.25.

- Jaworsky, B. N., and R. Qiaoan. 2021. “The Politics of Blaming: The Narrative Battle Between China and the US Over COVD-19.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26(2): 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09690-8.

- Jourde, C. 2007. “The International Relations of Small Neoauthoritarian States: Islamism, Warlordism, and the Framing of Stability.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (2): 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00460.x

- Kang, D., M. Cheng, and S. McNeil. 2020. “China Clamps Down in Hidden Hunt for Coronavirus Origins.” Associated Press, December 30, 2020. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/united-nations-coronavirus-pandemic-china-only-on-ap-bats-24fbadc58cee3a40bca2ddf7a14d2955.

- Kiseleva, Y. 2015. “Russia’s Soft Power Discourse: Identity, Status and the Attraction of Power.” Politics 35(3-4): 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12100.

- Kowalski, B. 2021. “China’s Mask Diplomacy in Europe: Seeking Foreign Gratitude and Domestic Stability.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 50 (2): 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211007147.

- Kurlantzick, J. 2023. Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Larson, D. W., T. V. Paul, and W. C. Wohlforth. 2014. “Status and World Order.” In Status in World Politics, edited by T. V. Paul, D. W. Larson, and W. C. Wohlforth, 3–29. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Li, H. 2021. “Media Representation of China in the Time of Pandemic: A Comparative Study of Kenyan and Ethiopian Media.” Journal of African Media Studies 13(3): 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams_00057_1.

- Lin, H.-Y. 2021. “COVID-19 and American Attitudes Toward U.S.-China Disputes.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (1): 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09718-z.

- Lindberg, J., E. Bradshaw, and L. Lim. 2023. “The World According to China: Capturing and Analysing the Global Media Influence Strategies of a Superpower.” Pacific Journalism Review 29 (1–2): 182–204.

- Liu, H. 2020. Propaganda: Ideas, Discourses and its Legitimization. New York: Routledge.

- Loh, D. M. H., and B. Loke. 2023. “COVID-19 and the International Politics of Blame: Assessing China’s Crisis (Mis)Management Practices.” The China Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023000796.

- Lu, Y., J. Pan, and Y. Xu. 2021. “Public Sentiment on Chinese Social Media During the Emergence of COVID-19.” Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 1. https://doi.org/10.51685/jqd.2021.013.

- Marsh, V. 2023. Seeking Truth in International TV News: China, CGTN and the BBC. New York: Routledge.

- Mattingly, D., T. Incerti, C. Ju, C. Moreshead, S. Tanaka, and H. Yamagishi. Forthcoming. “Chinese Propaganda Persuades a Global Audience that the ‘China Model’ is Superior: Evidence from a 19-Country Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science. https://osf.io/preprints/osf/5cafd.

- Mattingly, D. C., and J. Sundquist. 2023. “When Does Online Public Diplomacy Succeed? Evidence from China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats.” Political Science Research and Methods 11 (4): 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.41.

- Mikolov, T., K. Chen, G. Corrado, and J. Dean. 2013. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv:1301.3781. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1301.3781.

- Miskimmon, A., B. O’Loughlin, and L. Roselle. 2013. Strategic Narratives: Communication Power and the New World Order. New York: Routledge.

- Morgan, P., and Y. Zheng. 2019a. “Old Bottle New Wine? The Evolution of China’s Aid in Africa 1956–2014.” Third World Quarterly 40 (7): 1283–1303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1573140.

- Morgan, P., and Y. Zheng. 2019b. “Tracing the Legacy: China’s Historical Aid and Contemporary Investment in Africa.” International Studies Quarterly 63 (3): 558–573. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz021.

- Nathan, A. 2015. “China’s Challenge.” Journal of Democracy 26 (1): 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0012.

- Nye, J. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books.

- Ooms, J. 2021. “cld3: Google’s Compact Language Detector 3.” R package version 1.4.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cld3.

- Owen, J. M. IV. 2010. The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Pan, J., Z. Shao, and Y. Xu. 2022. “How Government-Controlled Media Shifts Policy Attitudes Through Framing.” Political Science Research and Methods 10 (2): 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.35.

- Perepolkin, D. 2019. “polite: Be Nice on the Web.” R package version 0.1.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=polite.

- Qing, K. G., and J. Shiffman. 2015. “Beijing’s Covert Radio Network Airs China-Friendly News Across Washington, and the World.” Reuters. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://www.reutersagency.com/en/reutersbest/article/reuters-reveals-beijings-covert-radio-network-airs-china-friendly-news-across-washington-and-the-world/.

- Repnikova, M. 2022. Chinese Soft Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rolland, N. 2020. “China’s Vision for a New World Order.” The National Bureau of Asian Research, Special Report #83.

- Roselle, L., A. Miskimmon, and B. O’Loughlin. 2014. “Strategic Narrative: A New Means to Understand Soft Power.” Media, War & Conflict 7 (1): 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635213516696.

- Scharpf, A., C. Gläßel, and P. Edwards. 2023. “International Sports Events and Repression Autocracies: Evidence from the 1978 FIFA World Cup.” American Political Science Review 117 (3): 909–926. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000958.

- Sullivan, J., and W. Wang. 2023. “China’s ‘Wolf Warrior Diplomacy’: The Interaction of Formal Diplomacy and Cyber-Nationalism.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 52 (1): 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221079841.

- Telias, D., and F. Urdinez. 2022. “China’s Foreign Aid Political Drivers: Lessons from a Novel Dataset of Mask Diplomacy in Latin America During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 51 (1): 108–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211020763.

- Tsai, W.-H. 2017. “Enabling China’s Voice to Be Heard by the World: Ideas and Operations of the Chinese Communist Party’s External Propaganda System.” Problems of Post-Communism 64(3–4): 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1236667.

- Tsang, S., and O. Cheung. 2024. The Political Thought of Xi Jinping. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Van Dijk, R. J. L., and C. Y.-p. Lo. 2023. “The Effect of Chinese Vaccine Diplomacy During COVID-19 in the Philippines and Vietnam: A Multiple Case Study from a Soft Power Perspective.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10 (687): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02073-3.

- Van Ham, P. 2002. “Branding Territory: Inside the Wonderful Worlds of PR and IR Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 31 (2): 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298020310020101.

- Verma, R. 2020. “China’s Diplomacy and Changing the Covid-19 Narrative.” International Journal 75 (2): 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702020930054.

- Wang, Y. 2008. “Public Diplomacy and the Rise of Chinese Soft Power.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207312757.

- Wang, C. Y. 2023. “Changing Strategies and Mixed Agendas: Contradiction and Fragmentation Within China’s External Propaganda.” Journal of Contemporary China 32 (142): 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2022.2109808.

- Watanabe, K. 2021. “Latent Semantic Scaling: A Semisupervised Text Analysis Technique for New Domains and Languages.” Communication Methods and Measures 15 (2): 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1832976.

- Wells, L. T. Jr., and A. G. Wint. 1990. Marketing a Country: Promotion as a Tool for Attracting Foreign Investment. Washington, DC: International Finance Corporation.

- Wen, Y. 2021. “Branding and Legitimation: China’s Party Diplomacy Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.” China Review 21 (1): 55–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27005555.

- Wilson, J. L. 2015. “Russia and China Respond to Soft Power: Interpretation and Readaptation of a Western Concept.” Politics 35(3-4): 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12095.

- Xinhua. 2020a. “Full Text: Fighting COVID-19: China in Action”. Xinhua, June 6, 2020. Accessed January 9, 2024. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-06/07/c_139120424.htm.

- Xinhua. 2020b. “Xi Focus: Chronicle of Xi’s Leadership in China’s War Against Coronavirus.” Xinhua, September 3, 2020. Accessed January 9, 2024. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-09/07/c_139349538.htm.

- Xinhua. 2021. “Interview: China is a ‘Friend Indeed’ to Serbia – Serbian President.” Xinhua, February 10, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2024. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-02/10/c_139735679.htm.

- Zhao, K. 2015. “The Motivation Behind China’s Public Diplomacy.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 8 (2): 167–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pov005.

- Zhao, K. 2016. “China’s Rise and its Discursive Power Strategy.” Chinese Political Science Review 1 (3): 539–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0037-8.

- Zollinger, D. 2024. “Cleavage Identities in Voters’ Own Words: Harnessing Open-Ended Survey Responses.” American Journal of Political Science 68 (1): 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12743.