Abstract

Contraceptive self-care interventions are a promising approach to improving reproductive health. Reproductive empowerment, the capacity of individuals to achieve their reproductive goals, is recognised as a component of self-care. An improved understanding of the relationship between self-care and empowerment is needed to advance the design, implementation and scale-up of self-care interventions. We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature published from 2010 through 2020 to assess the relationship between reproductive empowerment and access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care. Our review adheres to PRISMA guidelines and is registered in PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). A total of 3036 unique records were screened and 37 studies met our inclusion criteria. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, were cross-sectional and had high risk of bias. Almost half included only women. Over 80% investigated male condoms. All but one study focused on use of self-care. We found positive relationships between condom use self-efficacy and use of/intention to use condoms. We found similar evidence for other self-care contraceptive methods, but the low number of studies and quality of the evidence precludes drawing strong conclusions. Few studies assessed causal relationships between empowerment and self-care, indicating that further research is warranted. Other underexplored areas include research on power with influential groups besides sexual partners, methods other than condoms, and access and acceptability of contraceptive self-care. Research using validated empowerment measures should be conducted in diverse geographies and populations including adolescents and men.

Résumé

Les interventions contraceptives autogérées sont une approche prometteuse pour améliorer la santé reproductive. L’autonomisation reproductive, la capacité des individus à réaliser leurs objectifs de procréation, est reconnue comme un élément de l’auto-prise en charge. Une meilleure compréhension de la relation entre l’auto-prise en charge et l’autonomisation est nécessaire pour faire progresser la conception, la mise en œuvre et l’élargissement des interventions autogérées. Nous avons mené un examen systématique des articles à comité de lecture et de la littérature grise publiés de 2010 à 2020 pour évaluer le lien entre l’autonomisation reproductive et l’accès à l’auto-prise en charge contraceptive, son acceptabilité, son utilisation ou l’intention de l’utiliser. Notre étude respecte les directives PRISMA et est enregistrée dans PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). Au total, 3036 fichiers uniques ont été examinés et 37 études ont réuni nos critères d’inclusion. La plupart des études avaient été menées dans des pays à revenu élevé, étaient transversales et couraient un risque élevé de partialité. Presque la moitié incluaient uniquement les femmes. Plus de 80% portaient sur les préservatifs masculins. Toutes les études sauf une se centraient sur le recours à l’auto-prise en charge. Nous avons trouvé des relations positives entre l’efficacité personnelle dans l’emploi de préservatifs et l’emploi/l’intention d’employer des préservatifs. Nous avons observé des données similaires pour d’autres méthodes contraceptives autogérées, mais le faible nombre d’études et la qualité des données empêchent de tirer des conclusions solides. Rares sont les études à avoir évalué les relations causales entre l’autonomisation et l’auto-prise en charge, ce qui indique que des recherches supplémentaires sont nécessaires. Parmi d’autres domaines inexplorés, il convient de citer la recherche sur le pouvoir de groupes influents autres que les partenaires sexuels, les méthodes différentes des préservatifs, ainsi que l’accès à l’auto-prise en charge contraceptive et son acceptabilité. Des recherches utilisant des mesures d’autonomisation validées devraient être réalisées dans diverses régions géographiques et groupes de population, notamment les adolescents et les hommes.

Resumen

Las intervenciones de autocuidado anticonceptivo son un enfoque prometedor para mejorar la salud reproductiva. El empoderamiento reproductivo, la capacidad de las personas para alcanzar sus metas reproductivas, es reconocido como un componente del autocuidado. Se necesita mejor comprensión de la relación entre el autocuidado y el empoderamiento para promover el diseño, la ejecución y la ampliación de intervenciones de autocuidado. Realizamos una revisión sistemática de la literatura revisada por pares y la literatura gris publicadas del 2010 al 2020 inclusive, con el fin de evaluar la relación entre el empoderamiento reproductivo y la accesibilidad, aceptabilidad, uso o intención de utilizar autocuidado anticonceptivo. Nuestra revisión cumple con las directrices de PRISMA y está registrada en PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235). Se examinó un total de 3036 registros únicos y 37 estudios reunieron nuestros criterios de inclusión. La mayoría de los estudios fueron realizados en países de altos ingresos, eran transversales y tenían alto riesgo de sesgo. Casi la mitad incluía solo a mujeres. Más del 80% investigó el condón masculino. Todos salvo un estudio se centraron en el uso del autocuidado. Encontramos relaciones positivas entre la autoeficacia para el uso del condón y el uso o la intención de usar condones. Encontramos evidencia similar para el autocuidado con otros métodos anticonceptivos, pero la poca cantidad de estudios y baja calidad de la evidencia nos impide sacar conclusiones firmes. Pocos estudios evaluaron las relaciones causales entre el empoderamiento y el autocuidado, lo cual indica que es necesario realizar más investigaciones. Otras áreas poco exploradas son: investigación sobre el poder con grupos influyentes además de parejas sexuales, métodos además de condones, y accesibilidad y aceptabilidad del autocuidado anticonceptivo. Se debe realizar investigaciones utilizando medidas de empoderamiento validado en diversas regiones geográficas y poblaciones, tales como adolescentes y hombres.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers self-care interventions one of the most promising approaches to improving health.Citation1 In their guideline on self-care interventions, the WHO broadly defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of the health provider.”Citation1 The guideline covers a range of voluntary family planning and reproductive health topics and makes recommendations on specific self-care interventions relevant to sexual and reproductive health. It also offers a framework for self-care based on a person-centred approach to health and well-being and includes key principles of human rights, ethics, and gender equality.

While work is ongoing to refine the definition of self-care, and contraceptive self-care interventions have only recently received heightened attention for their potentially transformative role in improving reproductive health, the family planning community has been working on different aspects of self-care for quite some time. Indeed, WHO notes in the guideline that recommendations already exist on several aspects of self-care and that one goal of the guideline was to bring together both new and existing WHO recommendations and good practice statements. Three new recommendations for self-care interventions for providing high-quality family planning services included self-administered injectable contraception, over-the-counter oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), and home-based ovulation predictor kits for fertility management. Several existing recommendations to provide high-quality family planning services were highlighted: (1) provision of a range of user-administered contraceptive methods as listed in the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (MEC),Citation2 including the combined contraceptive patch, combined contraceptive vaginal ring, progesterone-releasing vaginal ring, and barrier methods (e.g. male latex, male polyurethane, and female condoms; the diaphragm [with spermicide]; and the cervical cap); and (2) provision of up to a one-year supply of OCPs depending on the user’s preference and intended use. The guideline also highlights existing guidance on task sharing or task shifting to include different health worker cadres, as well as the individual user, to improve access to family planning, and draws attention to the notion that self-care goes beyond method use.

Since The Programme of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which highlighted family planning within a human rights framework,Citation3 there has been increased recognition of the importance of empowerment, particularly women’s empowerment, for a range of health and development outcomes.Citation4–7 More recently, the concept of reproductive empowerment has received growing attention as the dimension of empowerment that supports universal access to contraception and reproductive health care and facilitates the agency of individuals and couples to achieve their reproductive goals.Citation8–10

Reproductive empowerment is a broad concept with many subcomponents and related constructs. Several frameworks have been developed and focus on the various dimensions of reproductive empowerment, such as individual and structural power dynamics, as well as psychosocial processes, beginning with the existence of choice and progressing to the exercise and achievement of choice.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12 While the terminology may vary, reproductive empowerment is generally conceptualised as the result of the interaction between individual and structural factors.

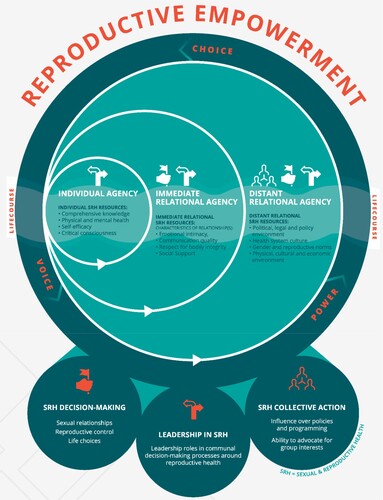

One such framework () developed by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) with funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and in partnership with MEASURE Evaluation, defines reproductive empowerment as:

Both a transformative process and an outcome, whereby individuals expand their capacity to make informed decisions about their reproductive lives, amplify their ability to participate meaningfully in public and private discussions related to sexuality, reproductive health and fertility, and act on their preferences to achieve desired reproductive outcomes, free from violence, retribution or fear.Citation8

At the core of this framework is “agency,” defined as individuals’ capacity to take deliberate actions to achieve their reproductive goals. We selected this framework because, unlike other models of empowerment, the ICRW framework focuses on agency within and across distinct individual, immediate relational and distant relational levels, and explicitly includes men. The authors of the framework further describe that,

within the context of specific social interactions at each of these levels, men and women express varying degrees of voice, choice and power, drawing on resources to enhance their agency, all of which are influenced by where they are in their reproductive life course. In the reproductive realm, this is expressed through the processes of decision-making, leadership, and collective action.Citation8

The WHO guideline on self-care interventions also describes aspects of the individual (e.g. self-reliance, empowerment, autonomy, personal responsibility, and self-efficacy) as well as the larger community as fundamental principles of self-care.Citation1 While the guideline states that reproductive empowerment and related constructs are elements of self-care, it also hypothesises that self-care may increase reproductive empowerment. For example, one of the research questions in the guideline is, “How might self-care interventions promote access, autonomy and empowerment without compromising safety and quality?” Further, we sought to investigate this relationship in the opposite direction, that is: Are self-care interventions more readily used by those who feel more empowered? This is important to assess to ensure self-care interventions are accessible to all who need or want these interventions. A better understanding of the relationship between self-care and reproductive empowerment is needed to advance the design, implementation, and scale-up of self-care interventions.

There is an absence of systematic review evidence for contraceptive self-care interventions and reproductive empowerment. To fill this gap, we conducted a systematic review of studies published in the peer-reviewed and grey literature to understand this relationship. Our review draws upon the ICRW framework and focuses on proximal aspects of individual and immediate relational agency, the resources which affect agency at these two levels, decision-making ability, and related concepts such as reproductive autonomy. In alignment with the WHO guideline we conceptualised contraceptive self-care broadly to include access, acceptability, use of or intention to use self-care contraceptive methods as well as self-care interventions using digital technology. Our objectives were to clarify the evidence base around the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment, and to document existing definitions, measures, and use of reproductive empowerment outcomes in relation to contraceptive self-care. The findings from this review may increase our understanding of when and why self-care interventions work or do not work. Researchers may also use the findings to guide their selection of reproductive empowerment measures for the study of contraceptive self-care, informed by measures that have been previously validated. Stakeholders could apply evidence from this review to inform their decisions about which self-care interventions to implement within their family planning programmes.

Methods

In conducting this systematic review, we adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelinesCitation13 and registered the review with PROSPERO (ID CRD42020205235).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they were published between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2020; were available in English; and reported primary quantitative or qualitative data on the relationship between access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment. We limited the review to the last 10 years to focus on the literature related to current discussions of contraceptive self-care. The populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes (PICO) frameworkCitation14 we used to define the search strategies were:

Population: Men and women of reproductive age; health care providers

Intervention: Contraceptive self-care

Comparison: Any or none

Outcomes: Quantitative or qualitative data on the relationships between reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care access, acceptability, use, or intention to use

We excluded secondary data analyses only when the primary data analysis also met the inclusion criteria, as well as non-research documents such as opinion pieces.

We followed the WHO guideline on self-care interventions to define the types of contraceptive self-care eligible for inclusionCitation1. Certain user-dependent methods were always considered self-care for this review: oral contraceptive pills (OCP), emergency contraception (EC), contraceptive vaginal ring (VR), contraceptive patch, rhythm method, cycle beads, withdrawal, male condom, female/internal condom, diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge, lactational amenorrhoea method, and spermicide. Other methods were considered self-care in certain circumstances: contraceptive injectables (when self-injected), intrauterine device (when self-removed), traditional/herbal methods (when self-administered), fertility awareness including digital apps and ovulation predictor kits (when used for pregnancy prevention), and urine pregnancy tests (when used for initiating a contraceptive method). Client-facing digital technologies were considered self-care if they (1) were accessible by clients with or without a health care provider and if they (2) were created to provide individualised information, guidance, or self-management of contraception to enhance access, acceptability, use of and/or intention to use contraception. These technologies included short message service (SMS) reminders, telehealth, smartphone apps, interactive voice response systems, chatbots, and decision aids. We excluded studies that combined self-care and non-self-care contraceptive methods (e.g. all contraception or modern methods) if they did not report results specifically for one or more of the self-care methods defined above. We also excluded studies which examined the use of male or female condoms solely for HIV prevention and did not study these methods as pregnancy prevention methods.

In defining reproductive empowerment, we focused on the two most proximal aspects of the ICRW Reproductive Empowerment framework, the individual level and the immediate relational levels, the constructs that the ICRW framework defined as “resources” that affect agency at these two levels, and related concepts such as reproductive autonomy. We used the following definition of reproductive autonomy offered by the authors of the Reproductive Autonomy ScaleCitation15: “having the power to decide about and control matters associated with contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbearing,” which we felt is consistent with the ICRW framework. Constructs eligible for inclusion included feeling empowered to make informed decisions about contraception, confidence in engaging in contraception method decision-making with a partner, and equitable power dynamics within a relationship. The broad constructs of knowledge and physical/mental health were not included in the scope of this review to allow focus on constructs more unique to empowerment. Studies were also eligible if they reported data on the inverse of these constructs, such as disempowerment, reproductive coercion, and presence of emotional, physical, sexual, or economic violence within the relationship. Studies were eligible if they assessed reproductive empowerment and related constructs whether they used validated or standardised scales, single survey items, or explored these concepts in qualitative interviews. While we included self-efficacy as it pertains specifically to reproductive empowerment, such as self-efficacy to negotiate contraception use, self-efficacy to use contraception correctly was not included, as this relates to knowledge of product use.

Information sources and search strategy

Our search strategy consisted of search terms related to the constructs of contraception, self-care, and reproductive empowerment (Appendix 1). We ran the search strategy in PubMed, Web of Science, Global Health, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Academic Search Premier. We also hand-searched bibliographies of manuscripts and grey literature to identify eligible studies and conducted a web search to identify additional references for screening and selection. We included grey literature, including electronically available conference proceedings, materials available in the USAID Development Experience Clearinghouse, the Knowledge SUCCESS and Harvard Dataverse websites, and potentially relevant organisational websites (PSI, Jhpiego, PMA2020, Marie Stopes International, and WHO). Two researchers reviewed each title, abstract, and full text independently to determine eligibility and resolved discrepancies through discussion and involvement of a third researcher as needed.

Data extraction and data items

One researcher, who served as the primary reviewer, conducted data extraction and risk of bias assessments using structured data extraction tables in the Covidence systematic review management and data extraction software. A second reviewer checked each entry for accuracy.

We collected study-specific data on country, study design, population and setting, and sample size; contraceptive method(s) and attributes; and sociodemographic factors, including age, marital status, parity, socioeconomic status, and urban/rural residence. In addition, we collected information on three main data items: access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care; reproductive empowerment construct, definition, and method of assessment (e.g. validated scale, single item); and relationships between the two constructs. We included results that were descriptive (e.g. observations of temporal trends or differences in proportions), statistical measures of association (e.g. cross-tabulations, regression analyses), and qualitative. We included data items that demonstrated findings on the relationships between access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment as well as the inverse of these two constructs; that is, data items that assessed how the lack of contraceptive self-care access or acceptability, or self-care non-use may relate to reproductive disempowerment measures were also included.

Risk of bias and quality assessments

We assessed the risk of bias for all studies reporting quantitative data using a standardised eight-item tool.Citation16 The presence or absence of the following was considered: a prospective cohort, a control or comparison group, pre/post-intervention data, random assignment of participants to the intervention, random selection of individuals for assessment, a follow-up rate of 80% or higher, equivalence of comparison groups based on sociodemographic measures, and equivalence of comparison groups at baseline for outcome measures. We considered studies to have low risk of bias if they possessed five or more of the eight items, and high risk of bias if they possessed four or fewer of the eight items.

For studies reporting qualitative data, we used a nine-item measure adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist,Citation17 to assess methodological quality according to the presence of a clear statement of research aims; the appropriateness of qualitative methodology, the research design for the research aims, and the recruitment strategy; whether data collection methods were appropriate to address the research topic, the relationship between research and participants had appropriately been considered, ethical issues had been adequately considered, and data analysis was sufficiently rigorous; and whether there was a clear statement of findings. We considered studies to be of good methodological quality if they possessed seven or more of the nine items, and to be of poor methodological quality if they possessed six or fewer of the nine items. No studies were excluded based on risk of bias.

Data synthesis

We summarised results by study type; whether access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care was measured; and the direction of the relationship between self-care and reproductive empowerment. To create a narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data from studies meeting the inclusion criteria, we summarised the evidence for relationships between reproductive empowerment constructs and contraceptive self-care and noted similarities or differences by geography, region, contraceptive self-care type, and other characteristics. In this review, we used WHO’s definitions of adolescents as individuals 10–19 years and young people as 10–24 years.Citation18 We considered evidence for favourable effects to be those that most public health practitioners would consider promoting of health and well-being: for example, more reproductive empowerment associated with more contraceptive use, or the opposite, less empowerment associated with less contraceptive use. Similarly, we considered evidence for unfavourable effects to be those that most practitioners would consider detrimental or harmful: for example, more reproductive empowerment associated with less contraceptive use, or the opposite, less empowerment associated with more contraceptive use. Null effects are those relationships that are not statistically significant or where no qualitative relationship was reported between self-care and reproductive empowerment. We also summarised the measures used in the included studies to systematically assess reproductive empowerment. Due to substantial heterogeneity in outcomes and directionality, we did not perform a meta-analysis.

Other considerations

We assessed selective reporting within studies according to standardised guidelines.Citation19 Because our objective was to synthesise evidence on multiple relationships between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment, we did not systematically assess confidence in the cumulative evidence. Instead, we took into account risk of bias of individual studies when assessing the evidence.

Results

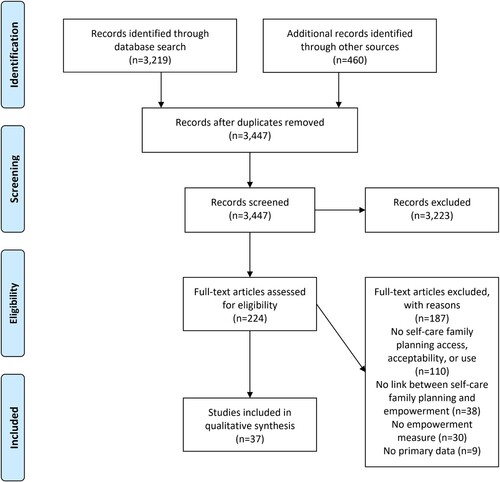

Our search strategy identified a total of 3219 references; after removing 191 duplicates and adding 460 references identified through hand-searching, we screened a total of 3447 unique records (). We excluded 3223 records during title and abstract review and assessed 224 records in full-text review. Thirty-seven studies published in the peer-reviewed (n = 36) and grey (n = 1) literature met our inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion were not reporting access, acceptability, use, or intention to use contraceptive self-care (n = 110); not assessing the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment (n = 38); and not measuring reproductive empowerment (n = 30).

A summary of the 37 studies which met the inclusion criteria is shown in . Nearly 30% of studies (n = 11) were from the United States and 8% (n = 3) from the United Kingdom. Two studies included participants from multiple countries. When grouped by continent, 14% of studies were conducted in Africa, 24% in Asia, 19% in Europe, 35% in North America, 3% in South America, and 3% in Oceania.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies (n=37)

Almost half of the studies (n = 18) included women only, and 43% (n = 16) included both women and men. Only three studies were of men only. The average age of participants across the 23 studies that reported discrete age was 21.4 years. Nearly half of the studies included only adolescents or young people and 38% focused only on adults. Sixteen percent of the studies included university students where the authors did not specify the students’ ages.

Regarding types of contraceptive self-care methods, most studies (81%; n = 30) investigated male condoms, four studies (10%) included client-facing digital technologies, four (10%) included OCPs, three (8%) included EC, and three (8%) included withdrawal. All other methods were only included in a single study that examined multiple methods. A total of five studies (14%) included more than one type of contraceptive self-care.

More than half of the studies (n = 21) employed cross-sectional research study designs, 19% used qualitative research designs, and 16% were randomised controlled trials. Three studies used quasi-experimental study designs. Among the 31 studies with quantitative data, 73% (n = 27) had a high risk of bias (Appendix 2). The most common study characteristics that resulted in a high risk of bias determination were lack of a cohort design, having no control or comparison group, and lacking pre- and post-intervention data. Of the seven studies presenting qualitative data, 86% (n = 6) were determined to have good methodological quality (Appendix 2). The most common methodological flaw in these studies was an inadequate consideration of the relationship between the researcher and the participant. The results and characteristics of each included study are presented in (additional information about the studies can be found in Appendix 3).

Table 2. Results

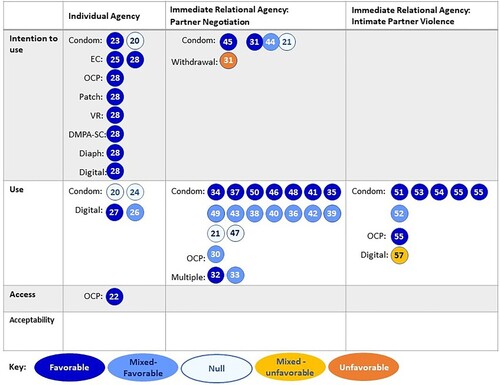

As described in the methods, we sought to understand the relationship between access, acceptability, use or intention to use contraceptive self-care and the individual and immediate relational agency aspects of the Reproductive Empowerment framework. provides a high-level summary of the studies by these self-care and reproductive empowerment constructs (individual studies are identified by reference number printed within the circle). All but one study focused on use of contraceptive self-care and, therefore, we further divided these studies into those which measured intention to use (n = 8) and those which measured actual use of contraceptive self-care (n = 28). Two studies measured both use and intention to use condoms.Citation21,Citation42 Only one study measured access to contraceptive self-care and none of the studies measured acceptability.Citation26 Regarding reproductive empowerment, eight studies measured individual agency constructs. The majority (29 of the 37) of studies examined immediate relational agency constructs. After reviewing the specific measures used within the immediate relational agency studies, we thematically grouped the studies by whether their empowerment measure focused on agency pertaining to (1) negotiation about contraceptive method use with partners or sexual negotiation with partners (n = 22) or (2) intimate partner violence (n = 7). The remaining eight studies measured individual agency constructs; no studies reported results across more than one empowerment construct. In , we represent each study that measured a specific type of contraceptive self-care with a circle; five studies have more than one circle because they measured more than one type.

Figure 3. Summary of the relationships between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment constructs

Each colour of the circles in indicates whether the relationship reported in the studies was favourable, unfavourable or null. Dark blue indicates that a favourable relationship was reported between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment (i.e. greater empowerment was associated with greater access/acceptability/use/intention to use self-care), whereas dark orange indicates that an unfavourable relationship was reported (i.e. greater empowerment was associated with lower access/acceptability/use/intention to use self-care). If the relationship between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment was not significant, we indicate the null results with the lightest blue. Since some studies conducted more than one analysis of the relationship between self-care and empowerment, they could have found mixed results. The middle shade of blue denotes studies that reported both null and favourable results. Yellow is used for studies that reported both null and unfavourable results. No studies reported a mix of favourable and unfavourable results.

Individual agency

Eight studies measured reproductive empowerment constructs related to individual agency, three of which measured its relationship with condoms only,Citation20–22 and five measured a relationship with types of contraceptive self-care methods other than condoms.Citation23–26,Citation57 This latter group included two studies of different client-facing digital technologies offering interactive decision support tools to provide contraceptive education and elicit users’ preferences for contraception.Citation24,Citation25 Two other studies in this group examined the relationship between individual agency empowerment constructs and OCPsCitation26 and EC.Citation23 The final study in this group, an online global values, and preferences survey conducted by WHO in 2019,Citation57 measured the perceptions of health care providers and “lay people” on whether empowerment is a top reason for using a variety of family planning methods, as well as their perceptions of whether empowerment is a benefit of using family planning. Respondents were asked about the following types of contraceptive self-care: OCPs, EC, patch, vaginal ring, self-injection of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC), diaphragm, and client-facing digital technologies.

Half of the studies measured intention to use contraceptive self-care. Three studies, including both studies of digital technologies, measured contraception use.Citation22,Citation24,Citation25 One study measured access to contraceptive self-care, though it measured hypothetical access to over-the-counter OCPs.Citation26

The individual agency empowerment constructs measured across the studies varied (). Three studies included multi-itemed scales with high internal consistency measuring general self-efficacy,Citation20 self-esteem,Citation22 and condom use self-efficacy.Citation21 One studyCitation24 measured decision quality using the multi-item Decisional Conflict Scale.Citation58 Three qualitative studies reported respondents’ single- or double-item empowerment statements such as feeling “empowered,” “in control,” or “prepared.”Citation23,Citation25,Citation26 WHO’s 2019 online survey measured respondents’ perceptions on family planning methods and empowerment by asking respondents two questions about potential method attributes using response options such as “access,” “convenience,” “privacy and confidentiality,” and “empowerment.”Citation57

Table 3. Measures of reproductive empowerment and related constructs

Only two studiesCitation20,Citation21 included both males and females (14–16 years and 13–18 years, respectively). Five studies focused on women with ages ranging from 13 to 45 years, including: girls 13–17 years,Citation22 women 15–30 years,Citation25 women 15–45 years,Citation24 women 18–44 years,Citation26 and women 20–40 years.Citation23 Respondents to the WHO 2019 survey included people from across the gender spectrum and ranged from 18 to 70 years. The WHO survey was the only study which included health care providers and met our inclusion criteria.

Five studies, including all three qualitative studies, found favourable relationships between individual agency empowerment and contraceptive self-care.Citation20,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26,Citation57 In one study, women 15–30 years were randomised to Contraception Choices, a digital decision support tool, or the standard of care; participants qualitatively described feeling empowered to talk to providers about their preferred contraceptive method and feeling more prepared for their appointments to discuss contraception.Citation25 Additionally, the study by Escribano et al. found a statistically significant positive effect of self-efficacy on intention to use condoms in structural equation modelling.Citation20 Two studies did not find a statistically significant relationship between their measures of empowerment (condom use self-efficacyCitation21 or self-esteemCitation22), and condom use. The study of the other digital decision tool had a significant effect based on one subscale of the Decisional Conflict Scale, where women 15–45 years randomised to the My Birth Control decision support tool had more decision certainty compared to those randomised to standard care. However, a significant effect was not found for the total scale.Citation24

Immediate relational agency: negotiation with partners

Twenty-two studies measured empowerment constructs related to immediate relational agency, specifically pertaining to negotiation about contraceptive method use with partners or sexual negotiation with partners. All but one study in this category measured condom use (n = 17) or intention to use condoms (n = 3) or both (n = 1). Nelson et al. measured adherence to OCPs with a single item asking the number of days women missed a dose of OCPs in the past three months.Citation49 In addition to measuring intention to use condoms, Agha also measured married men’s intention to use withdrawal.Citation46 Bui et al. measured third-year female undergraduate students’ use of contraception (defined as male condoms, EC, withdrawal, or rhythm method) at first sex as well as use of condoms only at first sex.Citation47 Do et al. 2012 examined use of what they defined as “couple methods,” which consisted of the following self-care methods: male and female condoms, diaphragm, foam, jelly, withdrawal, lactational amenorrhoea method, and periodic abstinence.Citation48

The reproductive empowerment measures used in most studies in this category examined condom use self-efficacy using either multiple item scales or single items. While the topics of the questions were similar (e.g. measuring respondent’s confidence in discussing and negotiating condom use with a partner), most studies used different measures and questions. The primary exception was the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES), which was used in five studies. Two studies used the full CUSES, one used an abbreviated version of the CUSES, one used only the Assertive subscale, and the study by Asante et al. examined both the total score of the CUSES and the Assertive subscale separately.Citation28 Slightly different from other studies, Xiao used a single item measuring the frequency of the respondent telling their partner they wanted to use a condom during sex over the past three months.Citation45 In addition to measuring condom use self-efficacy, Shih et al. used a single item asking who in the relationship had more say in condom use (response options: partner, participant, equal say, don’t talk about it).Citation38 Two studies, one qualitative and one quantitative, explored constructs of respondents feeling “responsible” for carrying condomsCitation29 or for “taking care” of contraception.Citation35 Do et al. measured five different constructs of empowerment consisting of a five-item economic index, six-item index assessing woman’s ability to negotiate sexual activity (such as refuse sex, ask partner to use condoms), and single-item (separate) measures asking who (woman alone or joint decision vs. other) decided whether women could visit their family and relatives, who made decisions about the woman’s health care, and whether the woman and her partner wanted the same number of children.Citation48

Six of the 22 studies included both male and female university students.Citation28,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37,Citation41,Citation45 Two other studies included students: a study by Sousa et al. included adolescent and young adult students 13–26 years,Citation40 and the study by Bui et al. included only female university students.Citation47 Eight other studies included adolescents or young people ranging in ages, including those as young as 10 years (n = 1Citation32, 13 years (n = 2Citation43,Citation44, 14 years (n = 3Citation34,Citation36,Citation38, 16 years (n = 1Citation39, and 18–24 years (n = 1Citation30. Do et al. 2012 included women 15–49 years currently married or cohabitating with a partner,Citation48 and a study by Nelson et al. included women 18–40 years selected from a health insurance cohort.Citation49 A qualitative study by Buston et al. included young men 16–21 at an institution for young offenders,Citation29 and another study that used quantitative methods studied married men 15–49 years.Citation46 Finally, two studies did not specify the ages of the respondents but included married women and what the authors described as a “community-based sample.”Citation29

Ten studies found favourable relationshipsCitation28,Citation29,Citation31,Citation34,Citation39,Citation41,Citation44–47, and 10 studies found mixed favourable relationshipsCitation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation43,Citation48,Citation49 (i.e. favourable and null effects) between reproductive empowerment (agency pertaining to negotiation with partners) and contraceptive self-care. For example, in a large study of university students, Santos et al. found that condom use self-efficacy scores using the Portuguese version of the CUSES were significantly higher among participants who reported using condoms vs. no contraception.Citation37 However, when examining differences by gender, the difference in condom use self-efficacy scores remained significant among males but was not statistically significant for females. Do et al.’s four-country study of five reproductive empowerment measures and their association with use of “couple methods,” also found a mix of positive and null results that varied by country.Citation48 In Namibia, although none of the individual measures of reproductive empowerment were found to be statistically associated with use of “couple methods,” an aggregated measure of empowerment was found to be significantly and positively associated with use of couple methods.Citation48 Statistically significant, positive associations were observed for sexual activity negotiation and use of couple methods in Zambia and Ghana, but significant results were not observed between these two constructs in Namibia and Uganda.Citation48 Significant positive relationships between agreement on fertility preferences and use of couple methods were only observed in Zambia and Uganda.Citation48 Lastly, a significant positive relationship between economic empowerment and use of “couple methods” was only observed in Uganda.Citation48

Two studies found no evidence of associations (i.e. null effect).Citation36,Citation42 For example, a study of sexually active African American females ages 14–20 years, found no statistically significant relationships between partner communication self-efficacy and condom use at last sex, or partner communication self-efficacy and the proportion of times condoms were used in the past six months, after adjusting for potential confounders.Citation36 The researchers used a reproductive empowerment measure containing six items with five-point Likert-type response options to assess perceived difficulty of talking with their male sexual partners about condom use and other sexual risk behaviours. Thomas et al. used the Assertiveness subscale of the CUSES and found no statistically significant differences in average assertiveness scores between participants who mostly or usually used condoms vs. those who did not use condoms, nor when comparing participants who intended to mostly or usually use condoms in the future vs. those who did not use condoms.Citation42

Only one study, by Agha, found a statistically significant negative association between married men’s reported ability to discuss family planning or ability to convince their spouse to use family planning (measured using a single item) and their intention to use withdrawal.Citation46 However, this same study also found a significant positive association between men’s ability to discuss family planning/convince spouse to use family planning and intention to use condoms.

All but one study examined the relationship between empowerment (agency pertaining to negotiation with partners) and contraceptive self-care using cross-sectional methods. The exception was a qualitative study by Buston et al., which found that young men 16–21 years at an institution for young offenders who reported consistent condom use described feeling responsible for carrying condoms with them and said they would use condoms to protect themselves from their partners becoming pregnant.Citation29 In contrast, men with infrequent condom use did not describe being in control of condom use and stated that their partners would ask for condoms to be used if needed.

Immediate relational agency: intimate partner violence

Seven studies measured reproductive empowerment constructs related to intimate partner violence (IPV), six of which measured condom use.Citation50–54,Citation56 In addition to measuring consistent condom use, Thiel de Bocanegra et al. also measured OCP use.Citation56 The final study tested a client-facing digital technology that included interactive voice-recorded messages providing tailored information about contraception and linking participants to a counsellor at a call centre for additional information.Citation55

The reproductive empowerment measures used in five studies included actual, threatened, or fear of physical violence from a partner.Citation50,Citation53–56 One study used multi-item measures of sexual aggression and the CUSES.Citation51 Another study measured reproductive coercion in the form of being “pressured, manipulated, or deceived” into having sex without a condom.Citation52

Five of the seven studies included women ranging from 15 to 49 years. The five studies individually focused on women with a history of drug use,Citation53 women at domestic violence shelters,Citation56 women who received menstrual regulation procedures,Citation55 married women using contraception,Citation54 and women attending university.Citation52 Only one study focused on adolescents – the study by Chiodo et al. included ninth-grade girls,Citation50 and only one study included young men.Citation51

Five studies found relationships in the expected direction between experiences of actual, threatened, or fear of physical violence from a partner and the lack of use of contraceptive self-care.Citation50,Citation52–54,Citation56 All five studies observed this relationship with condom use. The study by Thiel de Bocanegra et al. also reported that women in domestic violence shelters described that their abusive partners prevented them from using oral contraception by barring them from getting refills.Citation56 Similarly, in a qualitative study of female university students, almost half of participants described their male partners coercing them into having sex without a condom by questioning participants’ love, trust, or commitment to the relationship.Citation52 The remaining two studies included more than one analysis of the relationships between reproductive empowerment measures and contraceptive self-care use, and both found mixed results.Citation51,Citation55 For example, Davis found a statistically significant association between men’s sexual aggression severity and non-consensual condom removal but no significant association between condom use self-efficacy and non-consensual condom removal.Citation51 Reiss et al. found that women randomised to the client-facing digital technology intervention had statistically significantly higher odds of experiencing physical IPV because of being in the study but no higher odds of experiencing sexual IPV.Citation55

Assessments of reproductive empowerment and related constructs

We also collected information on the measures used to assess reproductive empowerment and related constructs in each of the included studies. A summary of validated and adapted empowerment measures is presented in . The vast majority of studies that used an existing measure were assessing factors related to condom use and assessed condom use self-efficacy with the CUSES or similar measures. Some studies assessed partner dynamics through measures of partner risk reduction self-efficacy, relationship control, and partner communication self-efficacy.Citation24,Citation30,Citation47 A couple of studies measured general self-efficacyCitation20 or self-esteem.Citation22 Notably, only one study used a more general measure of contraceptive self-efficacy, but this was not a validated measure and instead was a new scale the authors developed with influence from an existing scale.Citation49,Citation66 Although some studies reported that these scales had good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.80), few considered other aspects of the validity of these measures such as content validity and criterion validity.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic literature review to clarify the evidence base around the relationship between access, acceptability, use, and intention to use contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment. We also documented existing definitions, measures, and use of reproductive empowerment outcomes in relation to contraceptive self-care. Thirty-seven studies published from 2010 through 2020 met our inclusion criteria.

Given the broad and multi-dimensional nature of reproductive empowerment, we focused on the relationship between self-care and the individual and immediate relational agency aspects of the ICRW Reproductive Empowerment framework. Most studies used immediate relational agency empowerment measures, especially condom use self-efficacy. Moreover, within immediate relational agency, we found that most studies focused on negotiation about contraceptive method use with partners or sexual negotiation with partners, while some related to IPV. Further, while immediate relational agency is the largest group, it only focuses on power with sexual partners; notably absent are measures on power with other family members and with health care providers. The WHO survey included health care providers, but it measured individual-level agency and empowerment.

Due to the lack of research in the areas of self-care for methods that are not typically considered user-dependent (e.g. injectables, IUDs), most of the evidence in our review is about the relationship between reproductive empowerment and user-dependent contraceptive methods. Male condoms were the most studied type of contraceptive self-care. Just a few studies focused on OCPs, only three dealt with digital health interventions, and three included a range of contraceptive self-care types. Except for one study that asked about a wide range of methods, notably absent were studies measuring the relationship between empowerment and self-administered injectable contraception, despite this practice often being described as having the potential to empower women.Citation67–69 This will likely change as more research is conducted as the practice of self-injection expands. Also missing from the evidence base were studies of fertility awareness methods. More research is needed on the relationship between these understudied types of contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment. Further, when possible, studies should include multiple types of contraceptive self-care because there may be differences in reproductive empowerment constructs across different types of contraceptive self-care; some types may encourage more feelings of empowerment or be more readily used by those who feel more empowered, compared to other types. Such a relationship was observed in the study conducted by Agha, that found a negative relationship between married men’s reported ability to discuss family planning or convince their spouse to use family planning and intention to use withdrawal, but a positive relationship with intention to use condoms.Citation46

Use or intention to use were the most measured aspects of contraceptive self-care (specifically condoms), with only one study on access and no studies on acceptability in our review. A better understanding of acceptability and access could lead to effective interventions for increasing contraceptive use and would have an important role in building the evidence base for the relationship between reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care. Furthermore, it is important to note that use of a contraceptive method does not necessarily mean that the method is acceptable to users or meets their needs. Research on acceptability is particularly important because self-care relies on individuals’ acceptability of accessing and using self-care interventions without providers and/or outside of facility settings. In addition, increased understanding about the relationship between reproductive empowerment and acceptability of contraceptive self-care might help answer downstream questions about access and use. Research on access to contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment is needed to know whether self-care interventions are being equitably implemented. WHO describes equity as a key consideration for self-care to ensure that social and economic costs of accessing care do not shift to users, which would render access to self-care interventions out of reach for many who need or want these interventions.Citation1,Citation70

Most of the evidence available supports favourable relationships between condom use self-efficacy (being able to discuss and negotiate condom use with a sexual partner) and use of or intention to use condoms as a contraceptive method. This favourable relationship is further supported by five studies which found relationships in the expected direction between experiences of actual, threatened, or fear of physical violence from a partner and the lack of condom use. This relationship appears to extend to the limited evidence for types of contraceptive self-care other than condoms, but the low number of studies and low quality of the current evidence makes it challenging to draw strong conclusions. Further, the direction of the relationship between reproductive empowerment measures and access, acceptability, use and intention to use contraceptive self-care has been infrequently studied, and when explored, has been primarily studied using qualitative methods. However, the findings suggest a favourable relationship between the constructs and indicate that more investment in research to discern the direction of the relationship is warranted. In addition to understanding if self-care leads to empowerment, an understanding of the direction of the relationship between reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care will allow us to know also if those who feel more empowered are more likely to access contraceptive self-care interventions, and to further increase efforts to promote equitable access to these interventions.

Overall, the quality of the quantitative evidence was low. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs, which limits the evidence base for the presence or absence of causal relationships between contraceptive self-care and reproductive empowerment. Moreover, many studies used non-validated measures and frequently just one or two items to measure empowerment. When validated scales were used, they mainly focused on measuring self-efficacy to use methods, especially to use condoms. Several other validated measures of empowerment exist which measure constructs other than self-efficacy, for example, the Reproductive Autonomy Scale and the Reproductive Empowerment Scale.Citation15,Citation71 However, studies that have used these scales did not meet our inclusion criteria. These measures should be considered for future studies on self-care. In addition to the lack of consistency in the reproductive empowerment measures used, the study populations, designs, and analysis approaches varied, making comparisons across studies challenging.

The populations who met the inclusion criteria for the studies included in the review were not diverse in terms of geography or gender. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, and most included only women. Few of the studies included men, who were notably absent in the studies exploring IPV empowerment measures. This is particularly concerning because studies of power should include both those with and without power.Citation72,Citation73 However, men were included in more studies examining contraceptive method and sexual negotiation with partners. This category also included more studies that focused on adolescents. Overall, nearly half of the studies included adolescents or young people, which is welcome given the high unmet need for family planning among young people.Citation74,Citation75 However, many of the studies that included adolescents and young people did not report age-disaggregated results, which is recommended for studies examining power dynamics.Citation76,Citation77

Limitations

To keep the scope of the review manageable, knowledge, physical/mental health, societal factors, and norms related to empowerment were not included by design. Though these aspects of empowerment are important, our analysis of two aspects of the ICRW Reproductive Empowerment framework revealed many important gaps at both the individual and immediate relational levels in the field of family planning and reproductive health. Another limitation of this review is that we excluded studies which lumped methods together (e.g. all contraception or modern methods) if they did not report results specifically for the self-care contraceptive methods defined in the inclusion criteria. We also did not further examine the frequency or timing of use of contraceptive self-care. For example, some studies measured condom use during first sex while others measured condom use during most recent sex which may relate differently to empowerment. It was also beyond the scope of this review to examine whether the use or non-use of contraceptive self-care was an informed choice though this should be examined in future.

Conclusions and next steps

While recent research and family planning programmes focused on promoting “self-care” emphasise the potential for methods like injectables and others that have received recent attention, there is a dearth of research on how these approaches relate to reproductive empowerment. We found positive relationships between condom use self-efficacy and use of/intention to use condoms. We found similar evidence for other self-care contraceptive methods, but the low number of studies and quality of the evidence precludes drawing strong conclusions. However, given that the evidence is not causal, we cannot draw conclusions on whether contraceptive self-care interventions empower users and if so how. This area needs further research. This review has shown that there are several unexplored and underexplored areas of reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care that need to be studied. These include more research in the areas of individual agency and immediate relational agency, especially regarding power with other influential groups beyond partners. Likewise, we need to expand research on self-care contraceptive methods beyond condoms and extend self-care measures beyond use and intention to use to also include measures of access and acceptability. Researchers should also strive to use validated measures of reproductive empowerment and employ robust study designs that can elucidate the direction of effects between reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care. Finally, it is important that researchers generate information from additional geographies, and for specific subgroups such as adolescents and men, to ensure that everyone can benefit from the promise of contraceptive self-care interventions.

Supplemental Table 1. Studies excluded during full-text review and reason.

Download MS Word (268.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Carol Manion (FHI 360) who performed the search and Milenka Jean-Baptiste (UNC-CH FHI 360 fellow) who helped the team review abstracts. We appreciate Aurélie Brunie and Trinity Zan, both of FHI 360, for their review of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2022.2090057.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.2124030)

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- United Nations. Report of the International conference on population and development. New York: United Nations; 1995.

- Kabeer N. Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Change. 1999;30(3):435–464.

- Malhotra A, Schuler SR, Boender C, editors. Measuring women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. Background paper prepared for the World Bank Workshop on Poverty and Gender: New Perspectives; 2002.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls New York, NY: United Nations; 2021 [cited 2021 February 2]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5.

- United States Agency of International Development. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: 2020 policy. Washington (DC): United States Agency of International Development, 2020 2020. Report No.

- Edmeades J, Hinson L, Sebany M, et al. A conceptual framework for reproductive empowerment: empowering individuals and couples to improve their health. Washington DC: International Center for Research on Women; 2018.

- Karp C, Wood SN, Galadanci H, et al. “I am the master key that opens and locks”: presentation and application of a conceptual framework for women’s and girls’ empowerment in reproductive health. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113086.

- Moreau C, Karp C, Wood SN, et al. Reconceptualizing women’s and girls’ empowerment: a cross-cultural index for measuring progress toward improved sexual and reproductive health. Int Perspect Sexual Reproductive Health. 2020;46:187–198.

- Paul M, Mejia CM, Muyunda B, et al. Developing measures of reproductive empowerment: a qualitative study in Zambia. Chapel Hill (NC): MEASURE Evaluation; 2017.

- Wood SN, Karp C, Tsui A, et al. A sexual and reproductive empowerment framework to explore volitional sex in sub-Saharan Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2020;23:1–18.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

- Upadhyay UD, Dworkin SL, Weitz TA, et al. Development and validation of a reproductive autonomy scale. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(1):19–41.

- Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Armstrong KA, et al. The evidence project risk of bias tool: assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):1–10.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist 2017 [cited 2021 February 1]. Available from: http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Adolescence: a period needing special attention. Health for the World’s Adolescents: A second chance in the second decade. 2014.

- Catalogue of Bias Collaboration, Thomas ET, Heneghan C. Outcome reporting bias. In: Catalogue of Biases 2017 2017 [cited 2021 February 1]. Available from: https://catalogofbias.org/biases/outcome-reporting-bias/.

- Escribano S, Espada J, Morales A, et al. Mediation analysis of an effective sexual health promotion intervention for Spanish adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1850–1859.

- Espada JP, Morales A, Guillén-Riquelme A, et al. Predicting condom use in adolescents: a test of three socio-cognitive models using a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:35.

- Ghobadzadeh M, Sieving RE, Gloppen K. Positive youth development and contraceptive use consistency. J pediatr health care : Off publ Natl Assoc Pediatr Nurse Assoc Pract. 2016;30(4):308–316.

- Appleton NS. Critical ethnographic respect: womens’ narratives, material conditions, and emergency contraception in India. Anthropol Med. 2020;29:1–19.

- Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Fox E, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a patient-centered contraceptive decision support tool, My Birth Control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):565.e1–56.e12.

- Stephenson J, Bailey JV, Gubijev A, et al. An interactive website for informed contraception choice: randomised evaluation of contraception choices. Digital Health. 2020;6:2055207620936435.

- Sundstrom B, Smith E, Vyge K, et al. Moving oral contraceptives over the counter: theory-based formative research to design communication strategy. J Health Commun. 2020;25(4):313–322.

- World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights web supplement: global values and preferences survey report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Asante KO, Doku PN. Cultural adaptation of the Condom Use Self Efficacy Scale (CUSES) in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):227–233.

- Buston K, Parkes A, Wight D. High and low contraceptive use amongst young male offenders: a qualitative interview study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40(4):248–253.

- Chirinda W, Peltzer K. Correlates of inconsistent condom use among youth aged 18–24 years in South Africa. J Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2014;26(1):75–82.

- Do M, Fu H. Is women’s self-efficacy in negotiating sexual decisionmaking associated with condom use in marital relationships in Vietnam? Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42(4):273–282.

- Folayan MO, Odetoyinbo M, Harrison A. Differences in use of contraception by age, sex and HIV status of 10-19-year-old adolescents in Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;29(4):20150059.

- Gesselman AN, Ryan R, Yarber WL, et al. An exploratory test of a couples-based condom-use intervention designed to promote pleasurable and safer penile–vaginal sex among university students. J Am Coll Health. 2020:1–8.

- Krugu JK, Mevissen FE, Prinsen A, et al. Who’s that girl? A qualitative analysis of adolescent girls’ views on factors associated with teenage pregnancies in Bolgatanga, Ghana. Reprod Health. 2016;13:39.

- Long L, Han Y, Tong L, et al. Association between condom use and perspectives on contraceptive responsibility in different sexual relationships among sexually active college students in China: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2019;98(1):e13879–e.

- Ritchwood TD, Penn DC, DiClemente RJ, et al. Influence of sexual sensation-seeking on factors associated with risky sexual behaviour among African-American female adolescents. Sex Health. 2014;11(6):540–546.

- Santos MJO, Ferreira EMS, Ferreira M. Contraceptive behavior of Portuguese higher education students. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(suppl 4):1706–1713.

- Shih SL, Kebodeaux CA, Secura GM, et al. Baseline correlates of inconsistent and incorrect condom use among sexually active women in the contraceptive CHOICE project. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1012–1019.

- Smylie L, Clarke B, Doherty M, et al. The development and validation of sexual health indicators of Canadians aged 16-24 years. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC: 1974). 2013;128 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):53–61.

- Sousa CSP, Castro R, Pinheiro AKB, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the condom self-efficacy scale: application to Brazilian adolescents and young adults. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2018;25:e2991.

- Tafuri S, Martinelli D, Germinario C, et al. Determining factors for condom use: a survey of young Italian adults. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care : Off J Eur Soc Contracept. 2010;15(1):24–30.

- Thomas J, Shiels C, Gabbay MB. Modelling condom use: does the theory of planned behaviour explain condom use in a low risk, community sample? Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(4):463–472.

- Tingey L, Chambers R, Rosenstock S, et al. The impact of a sexual and reproductive health intervention for American Indian adolescents on predictors of condom use intention. JAdolesc Health: Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2017;60(3):284–291.

- Tsay S, Childs G, Cook-Heard D, et al. Correlates of condom self-efficacy in an incarcerated juvenile population. J Correct Health Care: Off J Natl Comm Correct Health Care. 2013;19(1):27–35.

- Xiao Z. Correlates of condom use among Chinese college students in Hunan province. AIDS Educ Prev: Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2012;24(5):469–482.

- Agha S. Intentions to use contraceptives in Pakistan: implications for behavior change campaigns. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:450.

- Bui TC, Markham CM, Ross MW, et al. Perceived gender inequality, sexual communication self-efficacy, and sexual behaviour among female undergraduate students in the Mekong delta of Vietnam. Sex Health. 2012;9(4):314–322.

- Do M, Kurimoto N. Women’s empowerment and choice of contraceptive methods in selected African countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38(1):23–33.

- Nelson HN, Borrero S, Lehman E, et al. Measuring oral contraceptive adherence using self-report versus pharmacy claims data. Contraception. 2017;96(6):453–459.

- Chiodo D, Crooks CV, Wolfe DA, et al. Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prev Sci : Off J Soc Prev Res. 2012;13(4):350–359.

- Davis KC. “Stealthing”: factors associated with young men’s nonconsensual condom removal. Health Psychol: Off J Div Health Psychol, Am Psychol Assoc. 2019;38(11):997–1000.

- Mitchell E, Bennett LR. Pressure and persuasion: young Fijian women’s experiences of sexual and reproductive coercion in romantic relationships. Violence Against Women. 2020;26(12–13):1555–1573.

- Sharma V, Sarna A, Tun W, et al. Women and substance use: a qualitative study on sexual and reproductive health of women who use drugs in Delhi, India. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018530.

- Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto K. Choice of contraceptive methods by women’s status: evidence from large-scale microdata in Nepal. Sex Reprod Healthc: Off J Swed Assoc Midwives. 2017;14:48–54.

- Reiss K, Andersen K, Pearson E, et al. Unintended consequences of mHealth interactive voice messages promoting contraceptive use after menstrual regulation in Bangladesh: intimate partner violence results from a randomized controlled trial. Glob Health: Sci Pract. 2019;7(3):386–403.

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Rostovtseva DP, Khera S, et al. Birth control sabotage and forced sex: experiences reported by women in domestic violence shelters. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):601–612.

- World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights web supplement: global values and preferences survey report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30.

- Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. J Am Coll Health. 1991;39(5):219–225.

- Hanna KM. An adolescent and young adult condom self-efficacy scale. J Pediatr Nurs. 1999;14(1):59–66.

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7):637–660.

- Espada JP, Ballester R, Huedo-Medina T, et al. Development of a new instrument to assess AIDS-related attitudes among Spanish Youngsters. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology. 2013;29(1):83–89.

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26(1):29–51.

- Espada JP, Gonzálvez MT, Orgilés M, et al. Validación de la Escala de Autoeficacia General con adolescentes españoles. Electron J Res Educ Psychol. 2017;10(26):355–370.

- Fedding CA, Rossi JS. Testing a model of situational self-efficacy for safer sex among college students: stage of change and gender-based diffewnces. Psychol Health. 1999;14(3):467–486.

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC, et al. Contraceptive self-efficacy: does it influence adolescents’ contraceptive use? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:45–60.

- Wynne L, Fischer S. Malawi’s self-care success story: rapid introduction of self-injectable contraception. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs; 2020; [cited 2021 February 2]. Available from: https://knowledgesuccess.org/2020/07/22/malawis-self-care-success-story-rapid-introduction-of-self-injectable-contraception/.

- Ministere de la Sante et de l’Action Sociale, JSI, PATH. Second DMPA-SC Evidence to Practice Meeting. Seattle, WA: PATH, 2019.

- Association for Reproductive and Family Health. Empowering women for a healthier future in Lagos State. Ibadan: Association for Reproductive and Family Health; 2019.

- Remme M, Narasimhan M, Wilson D, et al. Self care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights: costs, benefits, and financing. Br Med J. 2019;365.

- Upadhyay UD, Danza PY, Neilands TB, et al. Development and validation of the sexual and reproductive empowerment scale for adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68(1):86–94.

- Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: an examination of the evidence. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(3):189–213.

- McCarthy KJ, Mehta R, Haberland NA. Gender, power, and violence: a systematic review of measures and their association with male perpetration of IPV. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207091.

- Sully E, Biddlecom A, Darroch JE, et al. Adding it up: investing in sexual and reproductive health 2019. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2019.

- UNFPA. Facing the facts: adolescent girls and contraception. New York: United Nations Population Fund, 2015 2016. Report No.

- Morgan R, George A, Ssali S, et al. How to do (or not to do) … gender analysis in health systems research. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):1069–1078.

- Upadhyay UD, Gipson JD, Withers M, et al. Women’s empowerment and fertility: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2014;115:111–120.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Global Health, Academic Search Premier, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, APA PsycInfo

(contraception OR contraceptive OR contraceptive agents OR contraceptive devices OR “family planning” OR family planning services OR “contraception behavior” OR fertility OR “sexual health” OR “sexual wellness” OR “reproductive health” OR “reproductive behavior” OR miscarriage OR “post abortion care” OR “post-abortion care” OR (aftercare AND abortion) OR “Billings method” OR “CycleBeads” OR “Couple Beads” OR “rhythm method” OR “cycle beads” OR contraceptives, oral or “oral contraceptives” OR (“DMPA-SC” AND (“self-injection” OR “self-inject”)) OR Sayana Press OR ((intrauterine devices OR IUD OR IUDs) AND “self-removal”) OR ((“contraceptive ring” OR “contraceptive rings” OR ((vaginal ring” OR “intravaginal ring” OR “v-ring” OR “vaginal rings” OR “intravaginal rings” OR “v-rings” OR “progesterone-releasing vaginal ring”) AND contracept*) OR NuvaRing OR Ornibel OR Annovera) AND (annual OR yearly OR “once a year”)) OR withdrawal OR ((condoms OR condom OR “male condom” OR “male condoms”) AND (contracept* OR “family planning”)) OR ((condoms OR condom OR “male condom” OR “male condoms”) NOT (HIV OR “sexually transmitted diseases” OR “sexually transmitted infections” OR STDs OR STIs)) OR ((condoms, female OR “female condom” OR “female condoms”) AND (contracept* OR “family planning”)) OR ((condoms, female OR “female condom” OR “female condoms”) NOT (HIV OR “sexually transmitted diseases” OR “sexually transmitted infections” OR STDs OR STIs)) OR “vaginal diaphragm” OR “contraceptive diaphragm”OR “cervical cap” OR “vaginal sponge” OR “contraceptive sponge” OR “lactational amenorrhoea” OR “spermatocidal agents” OR spermicide OR spermicides OR “traditional contraceptive methods” OR “herbal contraceptives” OR (herbs AND contracept*) OR ((pregnancy tests AND (home OR self OR “over the counter”)) OR “home pregnancy test” OR “home pregnancy tests”) OR “spermatocidal agents” OR spermicide OR spermicides OR “postcoital contraception” OR “postcoital contraceptives” OR “emergency contraception” OR EC OR “traditional contraceptive methods” OR “herbal contraceptives” OR ((“pregnancy test” OR “pregnancy tests”) AND (home OR self OR “over the counter”))

OR “home pregnancy test” OR “home pregnancy tests”) OR (“ovulation detection” OR “ovulation prediction” OR “ovulation test” OR “ovulation testing”) AND (contracept* OR “family planning”)

OR SMS OR “short message service” OR “text messages” OR “fertility app” OR “digital app” OR “counseling application” OR “counseling app” OR “decision-making application” OR “decision-making app” OR “decision aid” OR “decision-making algorithm” OR “mobile-phone based” OR “interactive voice response” OR IVR OR “interactive voice message” OR “interactive response”

OR “mHealth” OR “eHealth” OR “mobile health” OR telemedicine OR “digital health”

OR “mobile technology”)

AND

(“self administration” OR “self-administration” OR “self administered” OR self medication OR “extended refill” OR “advanced provision” OR “over the counter” OR “without a prescription”

OR “multi-dosing” OR resupply OR “drug shop” OR “drug shops” OR ((pharmacy OR pharmacies) AND (“over the counter” OR “without a prescription”)) OR “community distribution” OR “community-based distribution” OR “self-injection” OR “self-inject” OR “self-testing” OR “self- referral” OR “self removal” OR self care OR “self-care” OR “self management” OR “self-management” OR “self concept” OR “self determination” OR “self efficacy” OR “self-efficacy”

OR “patient participation”)

AND

(empowerment OR empower OR “personal autonomy” OR autonomy OR “autonomous behavior” OR “autonomous choice” OR “autonomous decision making” OR “personal agency” OR “self-agency” OR “self agency” OR “self-determining” OR “self-determination” OR “self determination” OR decision making OR “decision making” OR “decision-making” OR “decision making, shared” OR “empowered decision making” OR freedom OR “freedom of movement” OR “personal freedom” OR “freedom of choice” OR choice behavior OR independence OR “personal independence” OR “independent choice” OR “independent behavior” OR power OR “personal power” OR “patient participation” OR gender based violence OR “gender-based violence” OR intimate partner violence OR “intimate partner violence” OR “power dynamics” OR “gender dynamics” OR “family relations” OR “family dynamics” OR “interpersonal relations” OR “reproductive autonomy” OR “self efficacy” OR “self-efficacy” OR paternalism OR “free will”

OR “power over self”)

Limited to 2010–2020

Limited to English

PubMed