Abstract

In 2018, WHO with the support of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India and partner organisations launched a Learning Districts Initiative to strengthen the district-level application of the National Adolescent Health Programme and to draw out lessons. An assessment of this initiative from 2019 to 2023 using qualitative and quantitative programme monitoring data from interviews, discussions, observations and data from multiple secondary sources explored the evolution of the concept, the process of securing government agreement, operationalising the initiative and the feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness and the potential of sustainability and replicability within the government health system. As part of the process, WHO developed the concept with partners to address the challenges identified in a Rapid Programme Review requested by the Ministry. The Ministry concurred with the proposed participatory problem identification and problem-solving approach. A review-based process guided the implementation. Local non-government organisations supported District Health Management Units to strengthen planning, implementation and monitoring. An expert in adolescent health provided technical oversight. Three years later in 2022, adolescent health is on district agendas, staff capacity has been built, and clinic and community-based activities are carried out in a structured manner. The Initiative is feasible as it leverages local expertise. Its core interventions are acceptable to government officials. While there are improvements in inputs, processes and outputs, these need to be independently validated. Challenges such as unfilled vacancies, problems in supply procurement, inability of staff to discuss sensitive issues, weak intersectoral convergence and low engagement of adolescents in programme management remain to be addressed. Nevertheless, the overall experience augurs well for the future of the programme.

Résumé

En 2018, l’OMS, avec le soutien du Ministère indien de la santé et du bien-être familial ainsi que d’organisations partenaires, a lancé une initiative des districts d’apprentissage pour renforcer la mise en œuvre au niveau des districts du programme national de santé des adolescents et en tirer des enseignements. Une évaluation de cette initiative utilisant des données qualitatives et quantitatives provenant de multiples sources a étudié l’évolution du concept, le processus d’obtention de l’agrément des autorités, la mise en œuvre de l’initiative, ainsi que sa faisabilité, son acceptabilité, son efficacité et son potentiel de viabilité et de transposabilité au sein du système de santé public. L’OMS a développé le concept avec ses partenaires pour s’attaquer aux difficultés identifiées lors d’un examen rapide du programme réalisé à la demande du Ministère qui a approuvé l’approche participative proposée pour l’identification et la résolution des problèmes. Un processus fondé sur l’examen a guidé la mise en œuvre. Les organisations non gouvernementales locales ont aidé les unités de gestion sanitaire des districts à renforcer la planification, la mise en œuvre et le suivi. Un expert en santé des adolescents a assuré la supervision technique. Trois ans plus tard, la santé des adolescents figure à l’ordre du jour des districts, les capacités du personnel ont été renforcées et les activités cliniques et communautaires sont menées de manière structurée. L’initiative est faisable car elle exploite l’expertise locale. Ses principales interventions sont acceptables pour les responsables gouvernementaux. Bien que des améliorations aient été apportées dans les intrants, les processus et les résultats, celles-ci doivent être validées de manière indépendante. Les difficultés comme les postes vacants non pourvus, les problèmes d’approvisionnement en fournitures, l’incapacité du personnel à parler des questions sensibles, la faible convergence intersectorielle et la médiocre participation des adolescents à la gestion du programme doivent encore être résolues. Néanmoins, l’expérience globale est de bon augure pour l’avenir du programme.

Resumen

En 2018, la OMS, con el apoyo del Ministerio de Salud y Bienestar Familiar, India y organizaciones aliadas, lanzó una Iniciativa de Distritos en Aprendizaje para fortalecer la aplicación a nivel distrital del Programa Nacional de Salud de Adolescentes, y para extraer lecciones. Una evaluación de esta iniciativa utilizando datos cualitativos y cuantitativos de múltiples fuentes exploró la evolución del concepto, el proceso de obtener el acuerdo del gobierno, operacionalizando la iniciativa, y la viabilidad, la aceptabilidad, la eficacia y el potencial de sostenibilidad y replicabilidad en el sistema de salud del gobierno. La OMS creó el concepto con socios para encarar los retos identificados en una revisión rápida del programa realizada a instancias del ministerio. El Ministerio coincidió con el propuesto enfoque participativo de identificación y resolución de problemas. Un proceso basado en la revisión guió la ejecución. Organizaciones no gubernamentales locales apoyaron a las Unidades de Gestión de Salud Distrital para fortalecer la planificación, la ejecución y el monitoreo. Un experto en salud de adolescentes proporcionó supervisión técnica. Tres años después, la salud de adolescentes figura en las agendas distritales, la capacidad del personal se ha desarrollado, y las actividades en centros de salud y en comunidades se llevan a cabo de una manera estructurada. La Iniciativa es factible, ya que aprovecha la experiencia y los conocimientos locales. Sus intervenciones fundamentales son aceptadas por los funcionarios del gobierno. Aunque hay mejoras en insumos, procesos y productos, estos deben validarse independientemente. Aún falta encarar retos tales como puestos vacantes, problemas en la adquisición de suministros, la incapacidad del personal para discutir asuntos delicados, débil convergencia intersectorial y poca participación de adolescentes en la gestión de programas. No obstante, la experiencia general es un buen augurio para el futuro del programa.

Introduction

Background

This paper describes a multi-level, multi-stakeholder initiative to strengthen district-level implementation of India’s National Adolescent Health Programme – Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) – in selected districts of the country, and draws out lessons from this effort for wider application. The effort involves the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), Government of India at national, state and district levels, United Nations (UN) agencies – the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), indigenous non-government organisations (NGOs) and a funding agency – the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

India has had national adolescent health programmes since 2005 – the Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy (ARSH) (2005–2012) and the RKSK (2014–present).Citation1,Citation2 The implementation of both these efforts has been funded primarily by the MOHFW, while both external and internal foundations and bilateral development agencies have supported complementary efforts by indigenous NGOs. Whereas some states and districts have identified adolescent health as a priority and moved forward energetically to implement the strategy/programme, many others have not. The substantial challenges in implementing the ARSH and subsequently RKSK in a large and diverse country in which health is a state subject, have been well recognised.Citation3–6 There have been and continue to be efforts to strengthen RKSK implementation. Some of them are focused on strengthening selected aspects of the RKSK with focused objectives such as reducing early pregnancy through increasing contraceptive uptakeCitation7 and reducing child marriage.Citation8 Others have focused on individual interventions that are part of RKSK: improving the quality of adolescent-friendly health service provision,Citation9 strengthening outreach education by health workers and peer educators (PEs),Citation10 and improving the organisation of adolescent health days (AHDs).Citation11 Recognising the need to strengthen the application of the RKSK Programme and to draw out lessons from it, the MOHFW supported a proposal made by WHO in conjunction with partners within and outside the UN, to put in place a Learning Districts Initiative (LDI).

This paper examines the development of the concept of the LDI, its operationalisation, preliminary results achieved in six districts of India, and experiences gained from its operationalisation, including challenges and opportunities.

Context in India

India has a large population of adolescents, estimated at 253 million in the last Census of 2011.Citation12 In 2018, the Centre for Catalyzing Change (C3) in association with the USAID’s Maternal Child Survival Plan Project conducted a national poll – “YouthBol” (Youth Speak) which involved about 100,000 10–24-year-olds – to learn and understand what adolescents and young people in the country want and expect from both the government and private health systems. More than a third of the adolescents and young people surveyed said that health was their top priority. They asked for better understanding and empathy from the community to their needs, a responsive, non-judgmental, confidential and affordable health system with special attention to substance abuse; management of menstruation, contraception and romantic relationships, and mental health issues including coping with academic pressure and dealing with violence.Citation13

There have been significant improvements in the social, nutritional and health status of adolescents in the country. A detailed overview of the situation of adolescents in India is beyond the scope of this paper; data on selected indicators presented provide a snapshot of the evolving situation in the country.

There has been an increase in school enrolment, narrowing of the gender gap in education and a decline in school dropout and work participation rates. The gross enrolment ratios (GERs) have increased from 86.7% in 2013 to 94.7% in 2022 in upper primary, and from 73.8% in 2013 to 79.6% in 2022 in secondary classes.Footnote* In the same period, the school dropout rates declined from 3.1% to 3.0% in upper primary and 14.5% to 12.6% in secondary classes. Both the increase in GER and the decline in dropout rate were more noteworthy among girls, reflecting an improvement in gender parity in education.Citation14 The decrease in dropout rate was even more significant among older girls in the 15–16 years age group.Citation15

There was a decline in work participation rates from 22.7% in 2001 to 16.8% in the 2011 Census of India, but there was a concurrent increase in school enrolment and literacy rates, suggesting that more adolescents are opting for education instead of joining the workforce at an early age.Citation16 The two consecutive National Family Health Surveys (NFHS 4 and NFHS5) reflected this decline in the age group 15–19 years (Girls: NFHS4 13.6%, NFHS5 11%; Boys: NFHS4 29.4%, NFHS5 27.3%).Citation17,Citation18

There has been a steady decline in levels of child marriage and adolescent pregnancy and in the adolescent fertility rate (National Family Health Survey, NFHS4 and NFHS5) and a significant increase in antenatal care, institutional delivery and postnatal check-ups as shown in (S1 File: State-wise performance). The vast majority of adolescents (>93%) in both NFHS were aware of modern contraceptive methods and there was an increase in their use among adolescent girls over the two NFHS, especially among the unmarried sexually active adolescent girls, as shown in .Citation17,Citation18

Table 1. Indicators with improved performance

While there are improvements in some areas of health as noted above, there are areas that still need focused attention as shown in (S2 File). There has been an increasing trend among adolescent girls and boys in the prevalence of anaemia and obesity. There is also an increase in the levels of gender-based violence. The National Commission for Women recorded more than a two-fold increase in reports of violence in the country during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic alone.Citation19

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic it was estimated that about a tenth of 5–15-year-old children have mental health issues and that there are about 20 million adolescents with severe mental health disorders. According to previous studies, 80–90% of adolescents with severe mental health disorders did not seek support.Citation20 The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated this situation. In a survey carried out by UNICEF and Gallup in early 2021 with 20,000 children and adults in 21 countries, while young people in other countries overwhelmingly talked about sharing their mental health issues with others and needing to seek help for these, more than half of young people in India did not do so, perhaps reflecting the stigma associated mental health issues.Citation21

Table 2. Indicators with a decline in performance

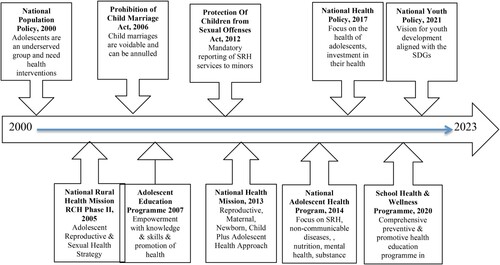

In recent years, India has emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world with increases in average incomes and millions reportedly being lifted out of poverty,Citation22 yet inequalities persist. Disparities on the lines of the rural–urban divide,Citation23 caste, region and gender exist.Citation17,Citation18,Citation24 These disparities affect individual wants, needs, choices and access to essential services, including those of adolescents. The Government of India is committed to the holistic health and development of adolescents. Its commitment is reflected through several national policies, laws and programmes. The timeline of their coming into existence and the critical dimension articulated is graphically depicted in .

The National Population Policy 2000 identifies adolescents as an underserved group for which health interventions were neededCitation25; the National Health Policy of 2017 acknowledges the health challenges of adolescents, the long-term potential of investing in their health care and school health programmes as a platform for reaching themCitation26; and the National Youth Policy, 2021 articulates a 10-year vision for youth development that is aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and aims to “unlock the potential of the youth to advance India”.Citation27

The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act or PCMA 2006 forbids child marriages and protects and provides assistance to victims of child marriages.Citation28 The Protections of Children from Sexual Offences Act or POCSO 2012 protects children (those below 18 years of age) from offences of sexual assault, sexual harassment and pornography.Citation29

The ARSH adopted under the Reproductive and Child Health Programme Phase II of the National Rural Health Mission (2005–2014) was meant to reorganise the existing government health system to provide health services to meet the reproductive and sexual health service needs of adolescents.Citation30 In 2013, the National Health Mission adopted the RMNCH + A (reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health) strategy that included adolescence as a distinct “life stage” for the “continuum of care” approach.Citation31 The National Adolescent Health Programme or RKSK was launched in 2014 to comprehensively address adolescent health needs.Citation32

Encouraged by the gains of government’s reforms in the education sector, and acknowledging that addressing health and education together underpins all Sustainable Development Goals and that the synergy has the potential to pay rich dividends, in 2020 the Government of India launched the “School Health and Wellness Programme”.Citation15,Citation33,Citation34 All these evolving programme, strategies are necessary to emerging needs of adolescents.

Objectives

The overall aim of the paper is to set out a comprehensive examination of the LDI and its bearing on prioritisation and execution of RKSK. To do this it examines in turn the LDI’s conceptualisation, operationalisation, implementation, potential for sustainability and its preliminary results in terms of addressing the gaps and weaknesses identified in the RKSK.

Authors were actively involved in conceptualisation, advocacy for and facilitation of implementation and monitoring of RKSK at district level as per the MoHFW guidelines and review and documentation of the LDI.

Methods

Research questions

The paper sets out to answer the following questions:

How was the concept of the LDI developed?

What did it take to secure agreement from the MOHFW about the LDI, and to establish formal working relationships with stakeholders at the national, state and district levels?

What was the process of operationalising the LDI?

What are the results in relation to the principal recommendations of WHO’s Rapid Programme Review (RPR) conducted in 2016?

Were the interventions put in place feasible, acceptable to different stakeholders and are they potentially sustainable and replicable within the existing government health system?

Data collection methods

Monitoring field visits were made to the first three districts addressed in the Initiative in 2018–2019. During these visits discussions were carried out with state, district (health and education officers) and block-level programme officials, representatives of mentoring organisations (project co-ordinators and programme managers), medical officers (MOs), staff nurses, adolescent health counsellors and frontline workers in the community (Accredited Social Health Activists or ASHAs and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives or ANMs) and PEs. We observed the functioning of at least one adolescent-friendly health clinic (AFHC), a peer education session, an AHD event and an Adolescent Friendly Club meeting at a subcentre (most peripheral rural facility in the country’s three-tier government health system). In addition, informal discussions were held with representatives of local NGOs working with adolescents if there were any. Additionally, the training of ASHAs and PEs was observed in one district where it was scheduled during the course of the monitoring visit.

However, these in-person visits were not possible during 2020, 2021 and 2022 due to COVID-19 restrictions. Given this, data was gathered from mentoring reports, key informant interviews and reviews of documents. The data from interviews, discussions and field visits were transcribed and were summarised along with review of documents as a brief field visit report.

The data gathering exercise addressed the five research questions described above. The research questions, methods used and sources of information are listed in .

Table 3: Research questions, data collection methods and sources

Data analysis

Mentoring organisations, the WHO India team member and an independent consultant hired for monitoring of LDI analysed the data in line with the five research questions. The analysis employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods (wherever possible) to provide a comprehensive understanding of the LDI and its effects on RKSK prioritisation and execution. Qualitative data analysis, including content analysis of reports, focussed on exploring emerging themes, patterns and quantitative data on the assessment of progress and achievements in comparison to the anticipated outcomes and the RPR’s recommendations (discussed later). The analysis methods for each research question are listed in .

Table 4. Research questions, data analysis methods

Site and timeline

The LDI has been implemented in three districts (Gumla, Jharkhand; Haridwar, Uttarakhand and Siddharthnagar, Uttar Pradesh) since 2018 and was scaled up to another three districts in 2020 (Agra, Uttar Pradesh; Dharwad, Karnataka and Sitamarhi, Bihar), as shown in the map in S1 Figure.

Ethics statement

The data that have been gathered, analysed and presented in this paper are programme monitoring data, following two and a half years of implementation. These data are part of the programme monitoring process of the government system with which partner agencies and mentoring organisations collaborated for implementation of LDI. Interviews, discussions and observations were carried out after assuring confidentiality of data and obtaining oral informed consent of participants.

Results

In the following section, we present our findings in relation to the five research questions.

How was the concept of the LDI developed?

In 2016, at the request of the MOHFW, WHO worked with Indian experts to carry out a RPR of RKSK’s implementation at the national level and in selected states, i.e. Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The RPR pointed to programmatic challenges across governance, implementation, intersectoral linkages and monitoring and evaluation.Citation35

Governance

The importance assigned to adolescent health by state and district government health officials varied from place to place but was generally low; key positions were vacant; processes for the use of funds were rigid (e.g. approvals to use funds were slow and the use of funds across work plan and budget line items was very difficult) and adolescent involvement in planning, implementation and monitoring was conspicuous by its absence.

Planning and implementation

Although AFHCs were functional, MOs were not always engaged in service provision; counselling services were available at few AFHCs as adolescent health counsellor posts were vacant; AHDs were conducted on an ad hoc basis and PEs lacked financial support and parental buy-in to sustain their involvement. Weekly Iron Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS) and the Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS) were either not functional or were affected by procurement and supply side challenges and the weak engagement of the relevant government departments.

Linkages

There were no formal systems for intersectoral coordination in planning and implementing RKSK and neither the Education nor the Women and Child Development (WCD) departments were meaningfully engaged.

Monitoring and evaluation

The focus of the programme monitoring focus was on inputs (such as training of different cadres of staff, or on adolescents’ use of health services) and not on process parameters, and there were challenges in monitoring programmes in the school setting such as the WIFS and MHS. Data were not generally used to inform implementation.

These findings were tabled and discussed at a meeting convened by the MOHFW in March 2017. At the MOHFW dissemination meeting, WHO was requested to develop a concept paper for a learning-by-doing initiative with a focus at the district level. WHO staff developed this paper in consultation with staff from the MAMTA Health Institute for Mother and Child, and the India country offices of UNFPA and UNICEF, and other partner organisations with experience in adolescent health programme delivery. The concept paper was developed in an iterative manner, with on-going inputs from the MOHFW, and was finalised in the last quarter of 2017. It was consistent with the WHO SEARO guidance document titled: “Strategic Guidance on Accelerating Actions for Adolescent Health in South-East Asia Region”, which seeks to strengthen existing national adolescent health programme by strengthening district-level health systems, and to make them more responsive to adolescents and youth.Citation36

Concept of the LDI

The goal of the LDI was to build the capacity of district programme management units (DPMUs) in evidence-based planning, implementation, monitoring, reporting and review of the RKSK, to document these experiences and to draw out the lessons learned.

The two complementary objectives of LDI were:

To support state programme management units (SPMUs) and DPMUs to plan, implement, monitor, report and review a context-specific package (based both on needs and on capacity) of health and social interventions to achieve clearly defined outcomes, in districts selected by the MOHFW, and

To determine the feasibility of delivering the intervention package at scale with quality and equity; its acceptability for those who would deliver them and for whom it was intended; to analyse its effectiveness in improving the desired outcomes; and to consider the sustainability and the replicability of the approach.

The three key principles of the implementation model included planning, implementation and monitoring faithful to the RKSK Programme; implementation by government staff using government resources and mentoring the DPMU by local organisations with expertise in adolescent health who were engaged to do this. Different stakeholders played complementary roles: national MOHFW would provide guidance and oversight and request selected state governments and relevant line departments to collaborate and support the LDI; the SPMU and DPMUs would be responsible for planning, implementation, monitoring and reviewing activities; and the mentoring organisations would support the DPMUs on an on-going basis. WHO would engage mentoring organisations, develop tools for planning, monitoring and evaluation, build the capacity of the mentoring organisations, and document the inputs and processes, experiences and learning.

What did it take to secure agreement from the MOHFW about the LDI, and to establish formal working relationships with stakeholders at the national, state and district levels?

In the March 2017 consultation, the MOHFW made it clear that that they were aware that the execution of the RKSK was moving forward slowly and unevenly and that they were open to ideas and suggestions to address this. They welcomed WHO’s proposal for a learning-by-doing approach and invited WHO to develop a concept note. As the development of the concept note for the LDI evolved, WHO kept the MOHFW informed on a regular basis. The MOHFW concurred with the proposed participatory problem identification, and problem-solving approach, with DPMUs in charge of the planning and execution of RKSK activities, and approved it in principle. In February 2018, a costing exercise was undertaken by WHO to provide an estimate of the financial needs for the activities proposed in the concept note – both for district-level planning, implementation, monitoring and review and for the provision of mentoring support by local organisations. The costing exercise took into account the funds available for RKSK within the programme implementation plan of the government as well as the need for additional funding. The MOHFW gave its concurrence on the understanding that the available National Health Mission funding would support RKSK-related planning, implementation, monitoring and review, and that UN partners would cover the costs of the mentoring support to be provided by local organisations. The MOHFW endorsement of budgetary responsibilities and approval of the concept gave it the official seal of approval as an initiative undertaken in partnership with the government. With the MOHFW on board, it opened the doors for seeking collaboration with other relevant stakeholders and further steps were taken to establish formal working relationships with stakeholders at national, state and district levels.

Launch of the RKSK LDI

In January 2018, the MOHFW and WHO organised a national-level planning meeting with UNFPA, UNICEF, USAID (partner agencies) and key NGOs, to discuss and agree on the proposed modus operandi for the LDI and to identify the districts to be involved.

In July 2018, the MOHFW launched the LDI at a meeting organised jointly with WHO. Following the meeting, the MOHFW issued a formal communication to the state governments where the LDI was to be implemented (in selected districts). That provided the basis for further engagement with them. The MOHFW also communicated its support for the LDI to international organisations and indigenous NGOs involved in the RKSK. This provided the basis for WHO to move forward in engaging them formally in the LDI.

At the state and district levels, WHO and the partner organisations established contact with the relevant government officials and built a working relationship with them, using the MOHFW communication as the point of departure.

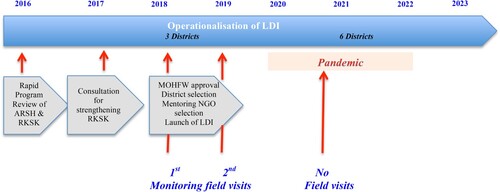

The timeline of development of concept, operationalisation and phases of implementation is graphically depicted in .

Early phases in the implementation of the LDI

The partner agencies and the mentoring organisations interacted with national, state and district authorities, keeping them informed about progress in the LDI. With the implementation in progress, regular quarterly reports were shared with state and district authorities. The consistent interactions, open sharing and joint decision-making – with DPMUs in charge – ensured that the working relationships became closer and stronger.

What was the process of operationalising the LDI?

Meetings continued to take place from July 2018 onwards with the proactive engagement of MOHFW and partner agencies in defining the criteria for the selection of the district-level mentoring organisations, developing guidelines for implementation of activities to address the four broad lines of gaps and weaknesses identified in the RPR, developing a monitoring framework with a short list of indicators, developing reporting formats and an Internet-based data-management mechanism.

Preparatory phase

Development of a toolkit for district-level managers: The MOHFW had developed guidance on planning, implementing, monitoring and reviewing titled “Implementation Guidelines – Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram”. To complement this with an operational approach, WHO worked with UN partner agencies, mentoring NGOs and MOHFW staff to develop a toolkit titled: “District Level Toolkit for Planning and Implementing RKSK in the Laboratory Districts: A Supplement to the 2018 MOHFW Implementation Guidelines for RKSK”.

The toolkit provides the rationale for the LDI, and its objectives, anticipated outputs and outcomes. It also provides detailed guidance on planning, implementation, monitoring and reviewing activities at the district level and the complementary actions that need to be taken to facilitate this at the state and national levels.

Development of a monitoring framework:

The toolkit proposes quarterly monitoring by the DPMU in collaboration with those in charge of health facilities. The current RKSK monthly report form requires district nodal officers to complete a total of 42 indicators, including 24 process indicators and 18 output/outcome indicators. As implementation was initiated, it became clear that it would be important to have a concise monitoring framework that covered the key activities that were being focused on. Through an in-person consultative process with partner organisations, currently used indicators on adolescent health as well as those relevant to the inputs, processes and anticipated outputs and outcomes under LDI were discussed and a prioritised set of indicators was identified. These indicators focus on processes and outputs both at the health facility and community level, and are in line with what has been proposed in the RKSK Strategy. The indicators and the process of measuring them are listed in S4 File and S5 File, respectively.

Selection of districts: The MOHFW at the national level led the identification of the districts to be included in the LDI based on the following criteria: the burden of mortality and morbidity in adolescents (e.g. adolescent pregnancies, malnutrition), the status of implementation of ARSH/RKSK, the representation of states, the availability of supporting health institutions and commitment from the district authorities. The MOHFW identified a short list of priority districts and allocated responsibility to the partner agencies as shown in . A number of these districts were designated “Aspirational Districts”.Footnote† The MOHFW then informed the respective state governments about its decision.

Table 5. Learning districts and partner agencies

Identification and engagement of mentoring organisations for the selected districts:

The concept note for the LDI lists the criteria for the selection of mentoring organisations. These are: proven expertise in adolescent health, experience in working with/supporting state and district governments in adolescent health programmes, a field presence in the states in which the LDI is to be implemented, and both capacity and willingness to support district-level implementation of RKSK. In consultation with the MOHFW, the Centre for Catalyzing Change was identified and engaged to provide support to Gumla in Jharkhand, and MAMTA Health Institute for Mother and Child for Haridwar in Uttarakhand, and Siddharthnagar in Uttar Pradesh. UNICEF, UNFPA and USAID made their own arrangements for the districts allocated to them.

Inception phase

Initial steps in mentoring district-level action (2018–2019): The chronological list of activities undertaken was as follows:

In July 2018, the LDI was formally launched. The rest of the third quarter of the year was devoted to engaging the mentoring organisations, and for them to make the administrative arrangements needed to deploy staff to support the districts. Their staff members established contact with the districts, carried out an assessment of the epidemiological situation and a mapping of the activities that were under way in relation to the RKSK operational manual.

Once this was done, they advocated with the DPMU for resources to address gaps and weaknesses in four areas – the shortage of human resources, the absence/inadequacy of AFHCs, the lack of trained frontline workers (ASHAs and ANMs) and the recruitment and training of PEs. Their staff members paid regular visits to the district for continued advocacy, and for providing technical support to the DPMU and the government staff in place, i.e. adolescent health counsellors, and frontline workers to strengthen implementation and monitoring/reporting.

A WHO India staff member and an independent expert conducted monitoring visits to the districts to review progress. Their review found that the rationale for the interventions they had selected was not always evident, and that arrangements for the effective implementation, monitoring and documentation work were uneven. From their review visits, they could see that the lack of functional structures and systems were hindering efforts to strengthen planning, implementation and monitoring. Given this, the outputs and outcomes of the interventions were uneven and limited in many areas.

Stepped up action phase – Structured planning reporting and reviewing (2019–2021):

In July 2019, at a meeting convened by the MOHFW and WHO, partner organisations (UNFPA, UNICEF, USAID and WHO) reported on progress in their districts. WHO reported on the findings of their on-site reviews in the inception phase. Following discussion, it was agreed that there would need to be a more structured planning, implementation, monitoring and reporting and review process. A template and a process were discussed and agreed upon. The mutually agreed process of planning, reporting and reviewing for WHO supported districts is graphically depicted in S2 Figure.

To respond to the need for a more structured and focused process, WHO developed a template for planning activities and guided the mentoring organisations in using it to develop plan for 2020.

As per the template, based on available data in the public domain on health issues of adolescents and service coverage, and based on prior experience in the geographical area, mentoring agencies worked with district health authorities to prioritise two adolescent health issues for focused attention in their action plan for the year. For each issue, they identified the groups of adolescents to be targeted. Next, they undertook an assessment of the current situation in terms of governance, implementation across both health facilities and community-based platforms, intersectoral linkages and monitoring and evaluation at the start of 2020, and their target for the year. Strategies for addressing the issues identified were proposed and the support needed to carry them out listed. Finally, measurable indicators and sources for these data for each indicator were identified. The health issues, the population groups, the strategies and indicators were consistent with the RKSK Strategy guidance. Since 2020, the mentoring agencies have been using this template for supporting DPMUs.

Monitoring and review

Regular monitoring and reporting of implementation were carried out by the mentoring agencies. In order to provide technical oversight to the learning districts and carry out an objective assessment, WHO engaged an external expert to monitor and review the plans and their implementation in the districts. This external monitoring involved a review of submitted annual reports as well as field visits (until the COVID-19 pandemic restricted travel to the districts). The expert referred to above reviewed the reports alongside the corresponding plans, and checked where progress had or had not been made, what opportunities arose and were tapped into, what challenges were faced and how they were overcome, and what innovations were tried. Feedback was provided to the individual mentoring agency team (and through them to the district team) and then discussed with WHO.

WHO organised annual review meetings of the mentoring organisations and district teams. This provided a forum for collaborative sharing and learning of where good progress had been made and where it had not, and what had helped and hindered this. The information from the meetings fed into the planning meetings which were also informed by presentations on changes in the situation (e.g. a huge increase in mental health needs in the context of COVID-19 disruptions and movement restrictions) and experiences (e.g. that of working with ASHAs to reach young pregnant women and young mothers in Maharashtra). While these meetings were in-person in 2019 and 2020, the one in 2021 had to be online. The chronological steps taken are listed in S6 File.

What are results in relation to the principal recommendations of the RPR?

The focus of the problem-solving/enhancement actions in the LDI was to support DPMUs in addressing the gaps and weaknesses identified in the RPR in relation to governance, implementation, intersectoral linkages and monitoring. The reports of the mentoring agencies and the external reviews suggest that tangible gains were made in each of these areas.

In relation to governance, the RPR recommended that District Committees for Adolescent Health (DCAH) are set up and made functional, all the posts specified by the MOHFW are filled and all the roles/responsibilities specified by the MOHFW are assigned, all staff members who are assigned these roles/responsibilities have the requisite competencies and the procurement of supplies is done in a manner that ensures that there is no stock-out. At the end of 2.5 years of implementation while adolescent health is on district-level agendas, DCAHs have not been set up in many districts but alternative platforms such as District Health Societies are playing the role; some vacancies have been filled, there still remain unfilled vacancies for key posts; and capacity building has been done, yet both managers and service providers report that they do not feel fully prepared to deliver all the interventions specified in the RKSK Programme Handbook. Procurement of supplies remains a challenge.

In relation to planning and implementation, the RPR recommended assuring that AFHCs are functional with competent service providers in place; planning, organising and monitoring of AHDs is carried out in a structured manner; and systems are put in place to facilitate the recruitment of PEs and to provide them with mentoring support as well as allowances (to cover travel expenses and some pocket money). It also called for procurement problems with the MHS and the WIFS programme to be addressed on a priority basis. At the end of 2.5 years of implementation, more AFHCs in all three districts (Gumla, Haridwar and Siddharthnagar) are functional; trained counsellors are providing counselling servicesFootnote‡; AHDs are being conducted and are being linked to AFHCs to facilitate referral and PEs have been recruited and a growing number of them have been trained. However, staff shortages mean that AFHCs are operational only for a few days a month, e.g. on days when counsellors carry out outreach, AFHCs remain closed. This also compromises the outreach work. Most PEs report that they are not comfortable in discussing sensitive or complex issues such as sexual behaviour and mental health concerns. Their interactions are restricted largely to “safe areas” such as menstrual hygiene and nutrition. Attrition of PEs in the absence of incentives continues to be a challenge. Supplies for MHS and reluctance of teachers to dispense Iron Folic Acid tablets because of apprehensions about side effects and their abilities to deal with them if they occur, affects both these ancillary programmes (MHS and WIFS).

The RPR identified intersectoral linkages as an especially weak aspect of RKSK programme implementation. It recommended a strategy to build meaningful convergence involving government departments and NGOs, across sectors relevant for adolescent health and wellbeing. It also called for the operations of these convergence mechanisms to be monitored. After 2.5 years of implementation, while district-level meetings involving staff from health, education and WCD occur more often than they did in the past, there is still no formal mechanism or structured process in place. Also, while frontline workers from these three departments collaborate in their routine work, e.g. in conducting AHDs, the active involvement of officials from these departments is limited, at best. This has affected coordinated implementation and reporting of programmes such as the MHS and WIFS.

In relation to monitoring and reporting, the RPR recommended that monitoring should go beyond administrative data on inputs (e.g. number of ANMs trained), and outputs (e.g. number of young people who visit a health facility or participate in an AHD event), to processes (e.g. the quality of counselling). It also recommended the institutionalisation of mechanisms to use monitoring data to feed into replanning and to strengthen implementation. Under the LDI, a short list of monitoring indicators was agreed upon by MOHFW, partner agencies and mentoring NGOs. At the end of 2.5 years of implementation, the reports from the districts and the independent reviews rely heavily on these indicators, and thereby provide a fuller picture of the implementation. These data are feeding into replanning under LDI on a half-yearly/annual basis.

One of the RPR’s crosscutting recommendations was, to ensure the participation and inclusion of adolescents and young people in all elements of RKSK, including governance, planning, implementation and monitoring. After 2.5 years of implementation, while they are included more than they were in the past, in the organisation of AHDs and PE sessions and in campaigns and special events, their involvement in other aspects of the programme remains non-existent.

To sum up, while tangible progress has been made in each of these areas, much more needs to be done.

Examples of district-level progress and results are presented in .

Table 6. Examples of district level progress towards ideal performance under LDI

Were the interventions feasible, acceptable to different stakeholders, and are they potentially sustainable within the existing government health system?

The core intervention of the LDI is to draw upon a locally-based NGO or another body such as a teaching institution to support DPMUs to prioritise RKSK and strengthen planning, implementation and monitoring of planned activities and their reporting by government staff – who are designated to carry out these functions – using resources provided by national and state levels of the government. This mentoring function is combined with learning-while-doing and sharing across the districts. After 2.5 years of implementation, reports suggest that the model works. So, the approach clearly is feasible.

The mentoring and collaborative learning approach is clearly acceptable to the mentoring agencies which are involved. Over time, it has become acceptable both to district managers and service providers in health facilities and in the community.

In terms of effectiveness, there are clear indications of process improvements in governance, planning, implementation, monitoring and reporting, and intersectoral linkages, as noted in the previous section. In some districts, this involved starting virtually from the scratch, e.g. in Siddharthnagar, whereas in others, it involved strengthening a programme that was already in place and functioning reasonably well, e.g. in Gumla. While these assertions are based on information from different sources that has been triangulated, they need to be further independently and closely examined. Also, although the focus of the LDI is on process improvement, there are signs of improved programme performance at the individual, family and community levels. For example, there is reported improved attendance at AFHCs, increased levels of care seeking from AH counsellors and helplines, better organised AHDs and better functioning PE sessions. There are also initial steps in improved participation by adolescents themselves.

It is worth noting that these achievements have occurred in the MOHFW’s Aspirational Districts, in which – by definition – health, education and social welfare systems were performing sub-optimally. Also, in the context of the COVID-19’s pandemic’s brutal second wave, when RKSK was not seen as a priority programme, human resources were redeployed for COVID-19 pandemic-related work; and movement restrictions and closures meant that planned activities were suspended or functioned at low levels leading to reductions in outreach programmes and in service utilisation.

As noted above, much more needs to be done in all four areas. In relation to governance, formal mechanisms to oversee RKSK’s operations need to be set up and/or empowered, key vacancies need to be filled, the performance of different cadres needs to be improved through the application of evidence-based approaches, and procurement processes need to be strengthened. Further, adolescents and young people need to be meaningfully involved in planning, implementation and monitoring. In relation to intersectoral linkages, formal coordination mechanisms involving health, education and child development departments need to be put in place, supported and tracked. Adequate staff need to be in place, health and education department staff need to have the capacity to deliver the relevant interventions, mechanisms to motivate and retain PEs need to be put in place, and appropriate indicators and reporting need to be integrated into existing information systems at the district, state and national levels.

For sustainability, the process changes in the functioning of DPMUs that have been made through the support of the mentoring organisations need to be further nurtured and institutionalised. These changes came about through better problem identification – based on local data – and solving on the one hand, and more diligent action planning and implementation on the other. Three years of experience has shown that there is capacity and willingness of NGOs to deliver the mentoring and collaborative learning interventions that lie at the heart of the LDI. Whether there is willingness and ability to institutionalise these arrangements in district- and state-level RKSK plans and budgets is the next logical question to be investigated in the next phase of the LDI. It heartening to learn that the LDI approach is already being applied in the context of other initiatives in India.Citation37

Discussion

In terms of conceptualising the LDI, the trigger was RPR of the ARSH and RKSK programme, which was carried out by WHO at the request of the MOHFW. The openness of the MOHFW officials to acknowledge the challenges in implementing RKSK and their readiness to look for the means of addressing this provided the basis for the development of the concept paper for the LDI, which was then approved. In terms of building working relationships with the state- and district-level decision makers, this was made possible by the MOHFW opening doors through formal communication. This initial step was followed by direct contacts with officials at the subnational level. In terms of operationalising the LDI, this was done through the development of programme support tools, the engagement of mentoring organisations and a learning-by-doing approach to support district-level planning, implementation and monitoring, which moved from a less to a more structured process with experience. In terms of the experiences gained and the lessons learned, the interventions that lie at the heart of the LDI approach are clearly feasible, acceptable to state and district-level managers, and suggest that they are effective in improving inputs, processes and outputs, though this needs to be independently and rigorously assessed. For the improvements that have occurred to be sustained, the mentoring and the collaborative learning processes will need to be institutionalised in state- and district-level work plans and budgets.

Our findings are consistent with findings in strengthening district-level programmes in child health. As Doherty and colleaguesCitation38 have noted, well-functioning district health systems are essential for planning and implementing health services, and their efforts are key to improve quality of care and achieving health goals. They stress that district teams are responsible for implementing and managing primary health care, but their responsibility comes without commensurate authority and resources; they often have insufficient management skills or resources to effectively implement the wide scope of programmes they oversee. Management training and coaching, integrated district planning processes and decentralised allocation of resources are essential; and embedded implementation research and district-to-district learning is likely to facilitate testing of strategies and enable local solutions to emerge. They provide case examples from Nepal and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where such approaches have been employed with promising results.Citation38 In the adolescent health field, investment in large-scale programming is relatively recent and experience in subnational level programming limited, relative to child health. An outstanding example is that of the national teenage pregnancy strategy in England. A national programme was put in place in 1999 and following a midterm review – as Hadley et al have described – a decision was made to provide intensive handholding support to poorly performing districts which contributed to improvements in local-level planning and execution.Citation39

There are three clear implications for action to strengthen district-level planning implementation and monitoring of the national adolescent health programme in India, based on the experiences gained in the LDI. First, there must be concerted advocacy to increase attention to adolescent health in DPMUs which have many competing priorities. Second, districts are at very different levels in terms of both the needs and problems of adolescence and in terms of district-level capacity to respond to them. Even within the LDI, there are districts such as Gumla, Jharkhand which has a much stronger programme than Siddharthnagar in Uttar Pradesh. This means that they need different levels of support. Thirdly, it would be useful to consider both what we want to see in place in ideal circumstances and what we insist must be in place at the bare minimum. This can then provide a clear pathway for quality improvement, coverage expansion and equity, that is tailored to local realities.

While there is a growing body of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions in improving knowledge, understanding, attitudes, norms, behaviours and health outcomes in adolescents in the context of research studies and pilot projects, there is a dearth of evidence on what it takes to apply these interventions at scale, while ensuring quality and equity in the context of government programmes. For India and a growing number of countries with government-led and government-financed – at least in part – programmes, implementation research in this area should be a priority moving forward. A recent study on the state of health service provision to adolescents in Rajasthan points to the pressing need for this.Citation40

The strengths of this review are that it is based on a logic model; it analyses progress alongside a set of indicators aligned to the logic model and consistent with those included in the RKSK Strategy, and draws together data from different sources and triangulates them. Its weakness is that it has been led and executed by those who have been directly involved in conceiving and operationalising the LDI and whilst this brought advantages in terms of access to data and knowledge of intended aims, it may have prevented a more critical evaluation. A planned independent evaluation should help to overcome these shortcomings.

While this paper is about India, the subject that it deals with has wider relevance. The situation in India is not unlike the situation in many countries in which governance is being decentralised from the national to the subnational level, with both positive and negative outcomes in terms of the leadership and management of health programmes.Citation41

Conclusions

The LDI has shown that it is feasible i.e. it can tap into the considerable expertise on adolescent health in indigenous NGOs and use that to strengthen district-level planning, implementation and monitoring. It has shown that its core interventions, i.e. mentoring support and collaborative learning, are acceptable to national, state and district officials. It has shown promising results in terms of improving inputs, processes and outputs. While these results need to be independently validated and while issues about the sustainability of the LDI need to be addressed, this augurs well for the future of India’s National Adolescent Health Programme.

Figure S1. Map of districts.

Download JPEG Image (174.2 KB)Figure S2. Planning and implementation process.

Download MS Word (95.8 KB)Table S1. State-wise performance.

Download MS Word (100 KB)Table S2. Logic model on problem statement.

Download MS Word (31.2 KB)Table S3. Logic model on interventions to address problems.

Download MS Word (33 KB)Table S4. Performance monitoring indicators.

Download MS Word (60.9 KB)Table S5. Measuring progress at the district level.

Download MS Word (53.8 KB)Table S6. A chronologic list of steps taken.

Download MS Word (51.4 KB)Author contributions

Alka Barua and Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli conceived the paper. Alka Barua, Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli, Rajesh Mehta and Swati Shinde prepared the drafts and shared them with all the co-authors, collated the feedback and prepared revised drafts. All the authors provided feedback on the first and subsequent drafts. All the authors read and approved the final draft.

Acknowledgements

The Learning District Initiative and its documentation is supported by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and executed by the Department of Reproductive Health and Research/Human Reproduction Programme, World Health Organization. We are grateful to the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India for its support in carrying out this initiative. We also acknowledge the sustained contribution of staff of Centre for Catalyzing Change, EngenderHealth, Family Planning Association of India and MAMTA Health Institute for Mother and Child to implementation of the initiative. We would especially like to acknowledge inputs, support and guidance of Dr Sunil Mehra, Executive Director, MAMTA throughout the course of this initiative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2283983.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* Class VI to VIII as a percent of the population in age 11–13 years and Class IX to X as a percent of the population in age 14–15 years Class IX to X as a percent of the population in age 14–15 years.

† Aspirational Districts: Under the New India Initiative, the Government of India identified 117 districts for fast-tracking the development agenda through focused and targeted interventions, indicator tracking and progress monitoring, with a multisectoral strategy involving all the relevant stakeholders.

‡ Counsellors in many places are using their initiative to “edu-tain” adolescents using flyers and video film clips downloaded from the Internet.

References

- National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Implementation guide on RCH II ARSH strategy: for state and district programme managers. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2006. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/arsh/guidelines/implementation_guide_on_rch-2.pdf.

- National Health Mission. Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram: strategy handbook. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2014. http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/rksk-strategy-handbook.pdf.

- Chauhan SL, Joshi BN, Raina N, et al. Utilization of quality assessments in improving adolescent reproductive and sexual health services in rural block of Maharashtra, India. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2018;5(4):1639–1646. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20181249

- Joshi B, Chauhan S, Kulkarni R, et al. Operationalizing adolescent health services at primary health care level in India: processes, challenges and outputs. Health. 2017;9:1–13. doi:10.4236/health.2017.91001

- Satia J. Challenges for adolescent health programmes: what is needed? Indian J Community Med. 2018;43:S1–S5. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_331_18

- Population Council. Priorities and opportunities for RKSK in Uttar Pradesh – policy brief. Population Council, New Delhi; 2017. https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2017PGY_UDAYA-RKSKPolicyBriefUP.pdf.

- Bose K, Martin K, Walsh K, et al. Scaling access to contraception for youth in urban slums: the challenge initiative's systems-based multi-pronged strategy for youth-friendly cities. Front Global Womens’ Health. 2021;2:673168. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2021.673168

- More than Brides Alliance. Strengthening the national adolescent health programme in India. More than Brides Alliance, New Delhi; 2021. https://morethanbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Strengthening-National-Adolescent-Health-Programme-in-India.pdf.

- Wadhwa R, Chaudhary N, Bisht N, et al. Improving adolescent health services across high priority districts in 6 states of India: learnings from an integrated reproductive maternal newborn child and adolescent health project. Indian J Community Med. 2018;43:S6–11. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_38_18

- Kansara K, Saxena D, Puwar T, et al. Convergence and outreach for successful implementation of Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram. Indian J Community Med. 2018;43:5, 18–5, 22. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_226_18

- Saxena D, Yasobant P, Puwar T, et al. Reveling adolescent health day: field experience from rural Gujarat, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2017;7:355–358.

- UNFPA. A profile of adolescents and youth in India. https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub.pdf/AProfileofAdolescentsandYouthinIndia_0.pdf.

- Center for Catalyzing Change. The YouthBol report: in brief; 2019. https://www.c3india.org/assets/c3india/ pdf/synopsis-of-youthbol-report.pdf.

- Ministry of Finance. School enrollment stands at 26.5 Crores. Posted on 31 January 2023 1:39PM by PIB Delhi; 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1894915.

- ASER Center and Pratham Network. Annual status of education report 2022; 2022. https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202022%20report%20pdfs/All%20India%20documents/aser2022nationalfindings.pdf.

- Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India & UNFPA. A profile of adolescents and youth in India; 2014. https://india.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/AProfileofAdolescentsandYouthinIndia_0.pdf.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), India, 2019-21: Mizoram. Mumbai: IIPS; 2021.

- Mittal S, Singh T. Gender based violence during COVID-19 pandemic: a mini-review. Front Global Women's Health. 2020;1. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2020.00004

- Shastri PC. Promotion and prevention in child mental health. Ind J Psychiatry. 2009;51(2):88–95. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.49447. PMID: 19823626; PMCID: PMC2755174.

- UNICEF. 2021. https://www.unicef.org/india/press-releases/unicef-report-spotlights-mental-health-impact-covid-19-children-and-young-people.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2019 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): Illuminating Inequalities. New York; 2019.

- Economic and Political Weekly. 2021, 56:45–46: https://www.epw.in/journal/2021/45-46/special-articles/rural-urban-disparity-standard-living-across.html.

- Global Gender Gap Report 2023. World Economic Forum (weforum.org).

- Department of Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National population policy 2000; 2002. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/ 26953755641410949469%20%281%29.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National health policy 2017; 2017. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/9147562941489753121.pdf.

- Department of Youth Affairs, Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India. National youth policy 2021; 2022. https://static.pib.gov.in/WriteReadData/specificdocs/documents/2022/may/doc20225553401.pdf.

- Government of India. The prohibition of child marriage act; 2006: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15943/1/the_prohibition_of_child_marriage_act%2C_2006.pdf.

- Government of India. The protection of children from sexual offenses act; 2012: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/POCSO%20Act%2C%202012.pdf.

- Government of India. Implementation guide on RCH II. Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Strategy; 2006. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/arsh/guidelines/implementation_guide_on_rch-2.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. A strategic approach to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH + A) in India; 2013. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/RMNCH+A/RMNCH+A_Strategy.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Implementation guidelines for Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram; 2018. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCHA/AH/guidelines/Implementation_Guidelines_Rashtriya_Kishor_Swasthya_Karyakram(RKSK)_2018.pdf.

- Ministry of Human Resources Development and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Operational guidelines on school health programme under Ayushman Bharat. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCHA/AH/guidelines/Operational_guidelines_on_School_Health_Programme_under_Ayushman_Bharat.pdf.

- UNICEF. Every girl and boy in school and learning. https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/education.

- Barua A, Watson K, Plesons M, et al. Adolescent health programming in India: a rapid review. BMC Reprod Health. 2020;17:87. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-00929-4

- WHO. Strategic guidance on accelerating actions for adolescent health in South-East Asia region - 2018–2022. WHO, SEARO. New Delhi; 2018.

- Mamta Health Institute for Mother and Child. Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram government and non-government organization partnerships for effective roll out and implementation. Mamta, New Delhi; 2021. https://mamta-himc.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/RKSK-Implementation-GO-NGO-partnership-document-002.pdf.

- Doherty T, Tran N, Sanders D, et al. Role of district health management teams in child health strategies. Br Med J. 2018;362. https://www.bmj.com/content/362/bmj.k2823.

- Hadley A, Ingham R, Chandra-Mouli V. Implementing the United Kingdom’s ten year teenage pregnancy strategy for England (1999-2010): how was this done and what did it achieve? BMC Reprod Health. 2016;13:139. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0255-4

- Dayal R, Gundi M. Assessment of the quality of sexual and reproductive health services delivered to adolescents at Ujala clinics: a qualitative study in Rajasthan, India. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261757. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261757

- Abimbola S, Baatiema L, Bigdeli M. The impacts of decentralization on health system equity, efficiency and resilience: a realist synthesis of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(8):605–617. doi:10.1093/heapol/czz055