ABSTRACT

Treatment options for college students with significantly functionally impairing mental illnesses are often limited. The Intensive Clinical Services (ICS) program is a Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)-informed, inclusive outpatient treatment option offered within a large Midwestern university’s counseling and psychiatric services center. The present study investigated the treatment effectiveness of the ICS program as well as the comparative effectiveness of telehealth and in-person service offerings. Statistical analyses demonstrated a significant reduction of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder and trauma-associated anxiety as well as reduction in overall emotional distress. While statistically equivalent symptom reduction was observed on most measures, telehealth service demonstrated greater reduction in overall distress compared with in-person treatment. These results suggest the potential utility of similar programs in university counseling centers, the adoption of which may ultimately expand access to collegiate education by encouraging recovery in place for students with functionally-impairing psychological disorders.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States has seen increased rates of mental health concerns among individuals of all age groups (Brunier & Drysdale, Citation2022). Social distancing and stay-at-home orders were public health strategies employed to reduce the spread of COVID-19, although these and other prevention strategies often contributed to experiences of loneliness and social isolation for many individuals (Teater et al., Citation2021). The consequences of the pandemic (e.g., deaths of loved ones, disruption in normative developmental experiences, hindered socialization) seemingly contributed to higher rates of depression and anxiety among children and young adults (Brunier & Drysdale, Citation2022). Recent large surveys conducted on college students indicate high rates of depression, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders within this population (Eisenberg et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020, see; Elharake et al., Citation2023 for a systematic review).

In addition to increased rates of psychological diagnoses, rates of non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors (NSSI; e.g., self-inflicted cutting, burning) and suicidal ideation, plan to die by suicide, and intent to die by suicide were also impacted by the global pandemic. Before the pandemic, Swannell et al. (Citation2014) reported international pooled prevalence rates of NSSI at 13.4% for young adults aged 18–24 years. In an examination of prevalence of NSSI during the pandemic, Lewis et al. (Citation2022) reported that approximately 80% of college students in their sample (N = 207) who reported engagement in NSSI prior to the pandemic reported decreased NSSI behavior and urges during the pandemic with 20% of their sample reporting increased NSSI behavior and urges during the pandemic. Suicide is currently the third leading cause of death among individuals aged from 15 to 24 and the second leading cause of death among individuals aged from 25 to 34 (NIMH, Citation2022). A meta-analysis of 54 studies with 62 participant samples indicated that female-identified individuals under the age 35 experienced increased suicidal ideation during the pandemic (Dubé et al., Citation2021), and some research suggests that college students who experienced severe COVID-19 infections exhibited elevated rates of suicide attempts (DeVylder, Zhou, & Oh, Citation2021). Suicide rates reportedly continue to increase for all age groups (Curtin, Citation2020).

While mental health concerns among the traditional college student population have risen, help seeking does not appear to display the same increase. In a 2021 study by Eisenberg and colleagues, approximately one-third of college students with mental health issues sought treatment, with substantial variance in rates of treatment-seeking across settings and populations (Eisenberg et al., Citation2021). Indeed, this study indicated that one in two college students who screened positive for depression and/or anxiety sought treatment after pandemic quarantine and stay-at-home orders, indicating a substantial service gap that has been documented by additional recent research (e.g., Ebert et al., Citation2019; Janota et al., Citation2022; Jeong, & Kim, Citation2021; Lipson et al., Citation2022). Approximately half of college students perceived public stigma related to receiving psychological treatment as a barrier to help seeking (Eisenberg et al., Citation2021), and a telehealth service modality did not appear to reduce perceived stigma (Hanley & Wyatt, Citation2020).

Racially and ethnically minoritized students, who experience significant mental health concerns at a greater rate than their White counterparts, appear to be less likely than White students to seek professional services to address mental health concerns (Lipson et al., Citation2022). A 2011 survey of 14,175 college students found that Black, Latinx, and Asian individuals were less likely to seek mental health treatment compared to their White peers (Eisenberg et al., Citation2011, Citation2012), and the main findings of this survey have been replicated in other research (e.g., Eisenberg et al., Citation2012; Kam et al., Citation2019; Masuda, Anderson, et al., Citation2009, Citation2009b). Continued applicability of this trend was evident in a 2022 analysis of Healthy Minds Study data (Lipson et al., Citation2022), which suggested a 33% increase in college students meeting diagnostic criteria for one or more mental health problems from 2013 to 2022; despite this increase in mental health issues among college students, a large inequity in help-seeking behavior and mental health utilization by race and ethnicity was observed. Lipson et al. (Citation2018) reported that 40% of students with mental health concerns received treatment for their concerns in the past year, and White college students exhibited the highest rate of receipt of treatment at 46%. In this study, students of color significantly less often received appropriate mental health diagnoses, used psychotropic medication, and received therapy compared to White students.

A growing body of literature suggests possible causes of racial disparities in help seeking. Researchers cite differences in cultural beliefs about the meaning, origin, expression, and treatment of mental health concerns as a barrier to formal help-seeking behavior (Cauce et al., Citation2002; Masuda, Anderson, et al., Citation2009, Citation2009b). Culturally-associated unfavorable attitudes toward professional mental health services (Masuda, Anderson, et al., Citation2009, Citation2009b; Nam et al., Citation2013) and stigmatizing perceptions of individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders (Masuda, Anderson, et al., Citation2009, Citation2009b) impact help seeking, as does uncertainty if non-minority providers will understand the experience of racially marginalized populations (Olaniyan, Citation2021). In addition to belief-based barriers to care, practical barriers are present. These include limited access to professional mental health care due to financial limitations (Miranda et al., Citation2015), lack of time to devote to treatment (Miranda et al., Citation2015), lack of available providers in some areas, and limited mental health literacy (i.e., the knowledge of mental health services and when and how to use those services) (Kam, Mendoza, & Masuda, Citation2019). Racial disparities in utilization of mental health services during a student’s college career warrant attention and consideration of social justice issues that impede care at university mental health service centers.

A particularly vulnerable college student population are those experiencing serious mental illnesses (SMI), for which this study adopted the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) SMI definition of “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” (NIMH, Citation1987; see; Zumstein & Riese, Citation2020 for various definitions of SMI and SPMI). Treatment options for college students with SMI are limited as university counseling centers (UCC), with few exceptions, typically offer brief individual and group counseling. Additionally, UCCs can rarely accommodate an integrated service package that would provide the most effective treatment for college students with SMI (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, Citation2022). Indeed, a 2022 report by the Center for Collegiate Mental Health noted that UCC clients’ average attended individual therapy appointments was 4.81 with a median of 3. Referral out to a higher level of care or specialized care was among the top 10 reasons for case closure (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, Citation2022). While intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment programs in the community are treatment options for those experiencing SMI, these programs can be costly and inaccessible due to limited availability, lengthy waiting periods for service, and unfeasible time commitments that may hinder continued enrollment in a student’s program of study. Students with SMI who display high-risk behaviors such as non-suicidal self-injury, significant substance use, impulsivity, or threats of violence often have even greater treatment needs. There is limited research examining the effectiveness of telehealth treatment services for those experiencing SMI or high-risk populations. Patients with SMI and/or substance use disorders “have traditionally been excluded from both treatments delivered through telehealth and research evaluating the efficacy of telehealth” (SAMHSA, Citation2021, p. 3).

To alleviate a lack of accessible mental health services for college students with SMI, Michigan State University (MSU) Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS) created the Intensive Clinical Services program (ICS) in 2018. The ICS program was modeled after Colorado State University’s (CSU) iTEAM, an on-campus intensive treatment program for students that utilized a multidisciplinary integrated care model with therapists, counselors, psychiatrists, case managers, and scheduling coordinators to provide students with individual and group DBT and psychotropic medication (CSU Health Network, Citationn.d.). Research suggests that a structured, psychoeducational, and skill-based short-term DBT-informed program can be highly effective in reducing the symptomatology of college students with borderline personality disorder and severely functionally impairing mental illnesses identified by affective rather than characterological psychopathology (see Chugani et al., Citation2013; Panepinto et al., Citation2015; Pistorello et al., Citation2012). During the pandemic, the ICS program briefly transitioned services to a telehealth delivery format, which was retained even after students returned to campus

Current study

The present study is a treatment outcome evaluation of MSU CAPS’ ICS program. The goals of this study are 1) to understand if there was statistically significant improvement in psychological symptoms pre- versus post-ICS treatment and 2) to evaluate the performance of telehealth versus in-person service delivery. Intensive Clinical Services participants were anticipated to demonstrate statistically significant symptom reduction on all treatment outcome measures in pre- and post-treatment data comparison. We further hypothesized that telehealth services would be statistically equivalent to in-person services such that equal benefit would be gained regardless of service delivery method. This study was reviewed by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board and, upon review, was determined to be exempt under 45 CFR 46.104(d) 4(ii).

Materials & methods

Program structure

The ICS treatment program offered time-limited, Dialectical Behavior Treatment-informed treatment within a culturally sensitive and integrated mental health treatment model to serve high-risk adults on a college campus. The ICS program provided students with individual and group psychotherapy, psychiatry, case management, and crisis intervention services, including a 24-hour crisis telephone line, as well as hospitalization and post-hospitalization support. Intensive Clinical Services participants were typically referred to the program upon screening for CAPS services, and participants were considered for program admission if they demonstrated persistent failure to meet treatment goals in other services and/or exhibited elevated suicide risk, diagnostic complexity and comorbidities, or met other inclusion criteria as detailed in Appendix A. The ICS program offered a trans-diagnostic treatment approach in which symptom severity and functional impairment in multiple life domains were emphasized during program screening rather than specific psychological diagnosis. Referral to ICS was clinically contraindicated in several circumstances, including when a student presented with imminent risk such that outpatient care would be insufficient to meet their needs. The ICS program was also not recommended to students experiencing unmanaged psychiatric symptoms that significantly impacted cognitive functioning such that meaningful participation in a skill-based group therapy would be jeopardized (e.g., student experiencing active mania). In these circumstances, greater psychiatric stability was required before a student would be considered for inclusion in the ICS program. Please see Appendix A for exclusion criteria.

Acceptance into the ICS program began with an initial access appointment, at which time discussion focused on the participant’s goals and treatment preferences, education about the ICS program, treatment duration estimation (e.g., 8-, 12-, 16-weeks), and establishment of mutual treatment expectations. The ultimate length of treatment was determined by a combination of participant preferences such as location (i.e., some participants returned to an out-of-state residence during the summer semester, thereby necessitating transfer of care to a licensed provider within their state of residence), risk factors, and capacity for treatment engagement; however, the average duration of an episode of care in ICS was approximately 14 weeks. Typical matriculation would then include an intake appointment and subsequent weekly individual and group therapy appointments. For example, an 8-week treatment plan in ICS included at least 16 scheduled appointments across individual & group treatment services with additional services such as case management provided as warranted. Case management services were intended to increase the inclusiveness of ICS by addressing barriers to treatment that racially and ethnically marginalized groups may experience in predominantly White institutions. For example, case management appointments may have included budgeting, education on mental health services to increase mental health literacy, problem solving barriers to continued treatment (e.g., collaborative problem solving of transportation issues), or promoting self-advocacy for campus resources (e.g., access to medical leave). Participant preferences for provider identity(ies) were honored whenever possible during provider assignment. Each participant’s cultural experiences and intersecting identities were integrated into case conceptualization and treatment recommendations by ICS providers. Modifications to the treatment model were also made when feasible based on cultural and identity considerations as well as clinical needs (e.g., providing individual DBT-informed skills training to a recent trauma survivor who could not yet tolerate co-ed group settings).

Treatment services description

Participants in this study attended weekly individual psychotherapy to reduce identified target behaviors, which were addressed in order of life-threatening, treatment-interfering, and quality of life-interfering behaviors in accordance with DBT behavioral hierarchy protocols (Dimeff & Linehan, Citation2001). Culturally-specific interventions (e.g., pastoral consultation, ancestral rites) were incorporated into the frequently employed Behavior Chain Analysis whenever relevant. Weekly group therapy focused on introducing and practicing DBT skills from the four modules of DBT (e.g., mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness) and utilized the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Training Manual, 2nd ed. (Linehan, Citation2015). The traditional phone coaching characteristic of full fidelity DBT treatment programs (Oliveira & Rizvi, Citation2018) was not offered; instead, participants were encouraged to utilize the counseling center’s telephone crisis line and/or individually drafted safety plans or scripts. Intensive Clinical Services providers, including individual and group therapy providers, nurses, and case managers, met thrice weekly to engage in consultation (Noll et al., Citation2020). The purpose of these meetings included service coordination and case consultation, group supervision of trainees, and support for ICS therapists. Additional ICS services were offered, including crisis walk-in services and brief family/support-system interventions. The program requirement was that participants meet at least once with a case management provider and psychiatric services provider, respectively, for consultation and recommendations. Most participants involved in this study were receiving psychotropic medication, although receipt of psychotropic medication was not a program requirement. See Appendix B for more detailed information.

Provider training & quality control

The clinicians who provided ICS treatment services were clinical psychologists, licensed clinical social workers, a licensed professional counselor, nursing staff, and psychiatry providers. The psychiatry and nursing providers intermittently attended ICS team meetings to support ICS’ integrated care model. Other staff members who provided treatment services were a limited license bachelors-level social worker and rotating multi-disciplinary interns. The ICS program director at the time of data collection, a licensed clinical psychologist, attended 40+ hours of DBT training by a Linehan-certified instructor. While other providers in the ICS program did not receive this extensive DBT training, numerous measures were taken to ensure that all ICS providers were competently offering DBT-informed interventions. For example, licensed individual and group treatment providers attended at least 12 hours of DBT training by a Linehan-certified provider and were provided individual clinical supervision at least monthly by the program director with additional phone/in-person support as needed. Intensive Clinical Services team members attended group supervision, as well as individual clinical supervision and consultation treatment team meetings. Doctoral psychology interns attended an eight-week ICS concentration training seminar provided biweekly across a semester; new licensed and unlicensed individual, group, and case management providers also attended this seminar when they onboarded into the ICS program. All licensed and unlicensed providers, apart from psychiatric residents and psychiatric providers, attended weekly experiential and/or didactic training supporting cultural sensitivity and multicultural engagement at least eight months of every calendar year as a component of site-based professional development. Additionally, ICS psychotherapy and case management providers participated in a chart audit twice per year.

Measures

The Borderline Symptoms List-23 (BSL23)

The BSL23 assesses severity of symptoms associated with BPD. While borderline personality disorder (BPD) was frequently diagnosed among ICS participants, the BSL23 was selected to broadly screen for maladaptive interpersonal patterns, emotional dysregulation, high risk behaviors, and other behavioral concerns commonly experienced by ICS participants. The BSL23 is a commonly used measure in personality disorder research; recently, researchers proposed new cutoff ranges to provide further clinical utility and support interpretation of results across a wide range of outcome literature (Kleindienst et al., Citation2020). This measure has demonstrated discriminant validity and test–retest reliability (Bohus et al., Citation2009). The racial demographics of the participant sample used in measure development research was not disclosed.

The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS)

The CCAPS is a well-validated collegiate mental health self-report measure typically used to assess a broad range of outcomes; this measure also demonstrated good test–retest reliability (Locke et al., Citation2011, Citation2012). The CCAPS Distress Index was employed to assess treatment outcomes as symptom-specific clusters varied widely across our sample due to a range of factors. As was the rationale for selection of the BSL23, the CCAPS Distress Index was utilized as an estimation of symptom severity irrespective of diagnostic categories. There are two versions of the CCAPS (62- and 34-items) that were used interchangeably in interpretation due to comparable percentile rank scoring and demonstration of convergent validity (Locke et al., Citation2011). The CCAPS-34 was validated in a sample of college students with limited racial diversity as most participants were white women (Locke et al., Citation2012).

Life Problems Inventory (LPI) & PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

There is a long-established correlation between the experience of trauma and diagnosable disorders such as BPD, substance use, depression, and other diagnoses that may be considered SMI (see e.g., Brady et al., Citation2021; Frias & Palma, Citation2015; Keane & Wolfe, Citation1990), thus warranting inclusion of a screening measure of trauma-associated symptoms. Therefore, the Life Problems Inventory (LPI) and, later in data collection, the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) was administered. The LPI is a 60-item self-report inventory often used in clinical research for BPD and other personality disorders (Rathus et al., Citation2015). The LPI was validated in a more diverse sample (63.6% Caucasian, 19.2% African American, 8.1% Hispanic.; Wagner et al., Citation2015). The LPI was validated for use in a college student sample and demonstrated construct validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability (Wagner et al., Citation2015). The PCL-5 was developed to screen for posttraumatic stress disorder and validated in civilian and veteran norming samples; adequate test–retest reliability, internal consistency, convergent, and discriminant validity and structural validity are established (Blevins et al., Citation2015). Regarding cross-cultural validity, civilian samples were only somewhat diverse displayed some diversity (e.g., one sample was 81.3% White and 11.5% African American; Blevins et al., Citation2015). The LPI was administered for a brief time period to only some participants before this measure was discontinued and the PCL-5 adopted. The decision to replace the lengthy LPI with the PCL-5 occurred mid-way through data collection in 2019, in part to reduce participant paperwork burden (see the Limitations section for discussion of the impact on study validity).

Data analysis

Data collection occurred from September 1, 2018 to July 30, 2021. Descriptive statistics, independent samples t-test and chi-square tests were used to characterize the participant sample. To explore the first goal of the study, namely understanding the treatment impact of the ICS program in the participant sample, a repeated samples t-test with the independent variable of time (i.e., before vs. after intervention) and dependent variables of measure scores was utilized. Several confirmatory analyses were also employed to better conceptualize the data, namely the repeated measures ANOVA with Wilks’ Lambda multivariate tests and Shapiro-Wilk’s tests for normality. To investigate the second goal of the study, evaluating the effectiveness of telehealth versus in-person services, null hypothesis statistical testing (NHST) was used. To determine the sameness or difference between in-person and telehealth service groups (i.e., equivalence testing; see Lakens, Citation2017 for a review), two one-sided tests (TOST) evaluated practically important differences on treatment outcome measures. These analyses were conducted on complete cases only, which resulted in substantial missing data. Some data were missing due to known factors such as programmatic changes (e.g., transition from LPI to PCL-5 as standard ICS participant test battery), while other data were missing due to attrition, participants declining to complete measures, and other factors. Multiple imputation was considered as a means of addressing missing data, but this method was not employed due to the volume of missing data (see the Limitations section for discussion of impact on study validity).

Results

Participant demographics

The total number of participants in the complete case sample was 91 with 60% (n = 55) receiving in-person services and 40% (n = 36) receiving telehealth services. Participants whose care with ICS had terminated at the time of analysis were included in this study sample, while data from participants who were still actively involved in ICS care were excluded from analyses. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 32 (M = 21.38, SD = 2.90) and predominantly identified as White (57.1%), followed by Black/African American (20.9%), Asian (8.8%), Multiracial (6.6%), Middle Eastern (5.5%), and Hispanic/Latinx (1.1%). In total, 42.9% of participants endorsed racial identities other than White. An independent samples t-test revealed no significant age differences between ICS participants who received in-person services (M = 21.62, SD = 3.26) compared to those participants who received telehealth services (M = 21.01, SD = 2.24), t(89) = .95, p > .05. Participants were predominantly cisgender women (72.5%), followed by cisgender men (18.7%) and gender non-conforming individuals (7.7%; e.g., non-binary, transgender, etc.). Chi-square analyses did not indicate statistically significant differences by group (i.e., in-person versus telehealth services) for race, X2 (5, N = 91) = 4.75, p > .05, or gender, X2 (3, N = 90) = 3.79, p > .05. Participants’ psychiatric diagnoses varied; the majority of the sample (57%) experienced three or more psychiatric diagnoses. The number of psychiatric diagnoses did not differ by participant group, X2 (2, N = 91) = 1.23, p > .05. Common diagnoses were severe major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, bipolar spectrum disorders, and comorbid substance use disorders.

All participants in this study were actively enrolled at Michigan State University with a small portion of participants on or pursuing medical leave from the University. All participants in this study voluntarily participated in the ICS program to address their identified treatment goals. There were no formal recruitment attempts made to secure or increase ICS participation. Referrals to the ICS program were typically submitted by CAPS general counseling providers, although some referrals were submitted by therapy providers at other university offices, various university departments (e.g., MSU Police and Public Safety, Residential Education and Housing Services), and, infrequently, self-referral and community provider referral.

Treatment characteristics

Although ICS is a short-term program with a typical duration of 8 to 16 weeks, flexibility in treatment duration was routinely offered to accommodate participant needs. This flexibility was particularly true in instances when participants were provided extended treatment to address social justice concerns that may be more frequently experienced by marginalized groups (e.g., inability to afford mental health care in the community due to underinsurance). The average length of ICS treatment in the study sample was 14 weeks (SD = 11.72, range = 1–82), and the in-person and telehealth treatment groups did not differ significantly in length of treatment, t(89) = .48, p > .05. The average rate of attendance for scheduled ICS individual therapy sessions was 73.22% (SD = 20.33), and there was a statistically significant difference by group such that the telehealth group (M = 84.62, SD = 11.21) exhibited greater attendance than the in-person service group (M = 67.21, SD = 21.53), t(82) = −4.07, p < .001). The majority of participants in the sample (65%) successfully completed the ICS program, which was defined by the ICS individual therapy provider’s clinical notation as to whether the participant had achieved stated treatment goals and/or voluntarily discontinued the program due to reduced psychological symptoms. The remaining participants (35%) were classified as program non-completers. The most frequent reasons for incompletion of the program were frequently occurring “no-show” appointments that necessitated program termination and referral, participant-initiated discontinuation from the program, and lack of participant follow-up to schedule regular appointments. Of note, treatment completion categorization (i.e., treatment completers vs. treatment non-completers) did not differ by race/ethnicity or participant group, X2 (1, N = 91) = 0.09, p > .05. For participants who did not complete the treatment program, limited data were available for analysis as these participants often did not respond to requests to complete final treatment outcome measures. However, in some cases, mid-treatment data were available as it was collected prior to the participant’s exit from the program; if this was the case, the most recent available measure data were included in data analysis. Additionally, the last CCAPS-34 Distress Index score was frequently available for program non-completers as all CAPS clients were requested to complete the CCAPS-34 prior to each individual therapy appointment.

Primary analyses

Results from the dependent samples t-test used to address the first goal of the present study are presented in . On all treatment outcome measures, ICS participants demonstrated statistically significant score reduction pre- versus post-ICS service completion (p < .001) for all measures except the BSL23 supplemental subscale, for which p < .01 with effect sizes ranging from small to large based on Cohen’s conventions (Citation1988). The repeated measures ANOVA with Wilks’ Lambda multivariate tests confirmed these results, but these tests were primarily utilized to display the data distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality (p < .05). Data were not normally distributed for two pre-treatment measures (i.e., BSL23 supplemental index, CCAPS-34 General Distress Index) and four post-treatment measures (i.e., BSL23 total, BSL23 supplemental index, CCAPS-34 General Distress Index, PCL-5); the results of the normality test are displayed in . Given substantial non-normal data distribution, a nonparametric test, namely the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test, was used to confirm the results of the dependent samples t-test as the assumption of data normality for the dependent samples t-test was frequently violated in the sample. presents the results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test, which confirmed the results of the dependent samples t-test in that all treatment measures demonstrated significantly higher pre-treatment mean scores compared to post-treatment mean scores.

Table 1. Dependent samples t-test comparing pre-treatment to post-treatment measure scores in total sample.

Table 2. Data distribution using Shapiro–Wilk test.

Table 3. Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test results.

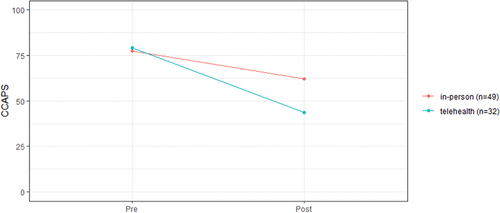

Equivalence testing using NHSTs and TOSTs was used to evaluate the sameness or difference of groups, namely the in-person service group and the telehealth service group. presents the results of the NHSTs, while presents the results of the TOSTs. Based on the combined results of the NHST and TOST, the BSL23 total score and BSL23 supplemental index were statistically not different from and were equivalent to zero; that is, participants receiving telehealth ICS services experienced statistically equivalent pre- versus post-treatment score reductions on the BSL23 measure compared to the in-person service group. The NHST and TOST results for the CCAPS-34 Distress Index revealed that pre- to post-treatment symptom reduction was statistically different from zero and statistically not equivalent to zero. The ICS participants who received telehealth services demonstrated significantly greater reduction in CCAPS-34 Distress Index total scores compared to the ICS participants who received in-person services (see ). NHST and TOST analyzes revealed that total scores on the PCL-5 were statistically not different from and were equivalent to zero. NHST and TOST analyzes were unable to be completed for the LPI given that the discontinuation of this measure prior to the pandemic resulted in no participants in the telehealth group.

Table 4. NHST results for equivalency determination.

Table 5. TOST results for equivalency determination.

Discussion

This study offers preliminary evidence supporting the use of integrated short-term DBT-informed mental health treatment as an effective intervention for symptom reduction in college students with significantly functionally impairing mental illnesses. The results from the repeated samples t-test showed that students who participated in the ICS program experienced a significant reduction of clinical symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder, general psychological distress, and trauma-associated anxiety symptoms. The implications for these results are broad. Early and effective intervention for individuals with SMI is a well-established factor for improved outcomes, including reduced suicide risk, improved long-term functioning, and reduced psychiatric hospitalizations (Debbané, M., & Sharp, Citation2020; Kelleher et al., Citation2013; McFarlane et al., Citation2015; Ratheesh et al., Citation2023). Additionally, the relationship between improved mental health and increased college retention rates is well documented (Center for Collegiate Mental Health, Citation2022). Mental health was among several other significant variables, such as financial stress, that affected retention decisions (Nieuwoudt & Pedler, Citation2023) and dropout anticipation in a diverse sample (McAfee et al., Citation2023). Of note, this study did not measure university retention or other functional ability indicators (e.g., reduced inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, improved grades).

The culturally inclusive nature of the ICS program and MSU Counseling and Psychiatric Services’ commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion places the ICS program in a unique position to serve students with social justice considerations, which the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (Citation2022) suggested is direly needed in on-campus mental health services. Individuals with SMI often have few specialized service options within the community to recover from acute psychological symptoms. Marginalized populations with SMI experience further disadvantage in accessing equitable mental health care that recognizes the impact of marginalization on mental health (Lo, Cheng, & Howell, Citation2014). Mental health services that acknowledge and welcome the intersecting identities of young adults attending college may result in improved treatment outcomes, which may increase academic functioning and reduce college attrition. For example, sexual and gender minority students anticipate dropping out of college at much higher rates compared to sexual and gender majority students. In fact, sexual and gender minority students’ psychiatric symptoms predicted anticipated school dropout more than a student’s sense of campus connectedness (McAfee et al., Citation2023). Effective mental health treatment that incorporates the unique experiences and stressors associated with minoritized sexual and gender identities may be key to retention. For these reasons, consideration of a program similar to ICS is warranted in campus-based mental health services.

When in-person ICS services were compared to telehealth ICS services, statistical equivalence was indicated on the BSL23, BSL23 Behavioral Supplement, and PCL-5. This finding suggested that telehealth services resulted in approximately the same symptom reduction on these measures as in-person services. The CCAPS Distress Index demonstrated statistical inequivalence; therefore, there was a greater observed symptom reduction on this measure in the telehealth group compared to the in-person group. Although statistical inequivalence on the CCAPS Distress Index does not align with our hypothesis, it is an exciting consideration that some symptomatology may display greater responsiveness to telehealth treatment modalities, even in high-risk populations participating in short-term treatment. This finding may be associated with the statistically significant increased attendance rate in the telehealth group compared to the in-person service group. Taken together, these findings suggest that telehealth and in-person evidence-based mental health services provide accessible, effective, interdisciplinary, and culturally inclusive treatment options for students with functionally impairing psychological disorders and/or high-risk behaviors.

The ICS may provide a framework for the adoption of similar programs in other university mental health service settings. Results of this study suggest the possibility of offering a multidisciplinary treatment team in a UCC setting. Indeed, the full-time staff devoted to the ICS program were few, but creative problem solving could be used in the event that full-time staff dedicated to this service is unfeasible (e.g., rotating staff assignment to a similar program). The ICS program highlights the importance of regular communication among providers and a team approach to mental health care, which implies that it can be replicated in UCCs by emphasizing appropriate connection with other treatment team members within the community or within the counseling center.

Limitations

This study provides preliminary data supporting the utility of an integrated treatment program for a diverse sample of college students experiencing SMI. However, the limitations of the study are significant. Therefore, the results of this study are best characterized as a suggestion of the program’s utility that warrants controlled research to determine its effectiveness. The study design introduced significant limitations. This study was quasi-experimental with no control group, an ethics-centered decision made to avoid a non-treatment waitlist condition for students who require timely intervention. As such, no causal conclusions regarding these results can be drawn from the present study. Furthermore, the generalizability of these results to larger populations is limited due to the small sample size that was collected from a single Midwestern university. The participant sample was gleaned through referrals from colleagues using their clinical discretion on their clients’ appropriateness for the program, introducing potential bias and unreliability given variable referral sources. Longitudinal treatment outcomes are undetermined due to site-based and resource limitations. As indicated above, the functional impact for students who participated in ICS was not measured (e.g., frequency of psychiatric hospitalization, academic retention). These variables are important and should be assessed in future research.

The quality of the data, including the treatment outcome measures as well as nonrandom missing data, also introduces limitations. As mentioned above, the LPI was discontinued in favor of adoption of the PCL-5 early in data collection, a significant confounding factor that may have introduced test bias and impacted statistical analyses. This decision, while practically useful for program operations, created inconsistency in the data and uncertainty in the attribution of symptom reduction to treatment rather than test variability. Replication of this study would require consistent tests used throughout data collection. The analyzed data included complete cases only, and the volume of missing data precluded the use of statistical techniques, such as multiple imputation to address the missing data. The missing data pose validity concerns as an unknown amount of data were not missing randomly. For example, some participants dropped out of the ICS program with no further contact, which could possibly be due to participant dissatisfaction or lack of progress in the program. In these cases, only some treatment outcome data were analyzed, such as the CCAPS Distress Index.

Provider selection and treatment administration also introduced limitations. Marked provider training differences existed in the study. Indeed, the wide range of provider training, from over 40 hours of DBT-focused training from a fully licensed psychologist to trainees in the midst of their predoctoral internship, likely impacted adherence to a DBT-informed model of treatment. It is likely that some analyzed data reflected treatment that deviated from typical DBT methods and techniques, despite close supervision that included video recorded individual treatment sessions. Additionally, it is important to note that treatment was DBT-informed rather than DBT-adherent. This decision was purposeful and allowed treatment flexibility to accommodate the clinical needs of each participant, including diversity and cultural considerations (e.g., neurodivergent participants requiring adaptations to DEAR MAN GIVE FAST interpersonal effectiveness skills to accommodate differing interpersonal interaction practices). Therefore, DBT techniques and interventions were variably administered, with some techniques likely being focused upon more than others, and the DBT interventions that were administered were not uniformly delivered across providers and participants.

Although the present study suggests successful implementation of the ICS program in a university counseling setting, the development of a similar program in a UCC may not be feasible. The ICS program does not offer the brief treatment that permits UCCs to assist the greatest number of help-seeking students. The application of a similar program in a university counseling center may be unrealistic or unsustainable given high clinical demand with limited provider support to meet that demand. Indeed, researchers reported increased counseling center staff turnover during the COVID-19 pandemic with 61.3% of UCCs reporting staffing changes (Gorman et al., Citation2022). A study conducted by Gorman et al. (Citation2021) suggested that, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the utilization of services at university counseling centers increased by 13%; however, the average number of clinical providers to meet the increased demand was unchanged. The increase in clinical demand, staff turnover, and clinical presentation severity present unique challenges for the formation of a similar treatment team in a university counseling center. High demand coupled with limited provider support for serving students demonstrating high-risk behaviors may lead to clinician burnout and turnover. Hiring issues may also impact adoption of a similar program as attracting and retaining qualified clinical providers may prove difficult. Finally, many UCCs have limited or no psychiatric services, making integration of psychiatric care into their treatment models dependent on sustained connection to psychiatry providers or medical providers in the community.

Future directions

Controlled research that addresses the aforementioned limitations is necessary to investigate the impact of similar treatment programs within university settings. If controlled research demonstrates program effectiveness, future research may compare treatment effectiveness across a variety of participant identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation) given that treatment effectiveness for diverse populations is crucial. Interested researchers may study the effectiveness of other evidence-based treatment approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, for individuals with severely functionally impairing mental illnesses. Future researchers may wish to consider incorporating other components of an integrated treatment approach, such as greater inclusion of family/supportive others in treatment. Another area of investigation may be the relationship between inclusion of a short-term, integrated treatment program and potential mitigation of burnout and turnover with college counseling staff; perhaps a short-term, team approach to clinical care may interest some providers such that these providers chose to remain engaged in their career in collegiate mental health services. The impact of telehealth delivery to this population of college students certainly warrants further examination to understand specific circumstances and factors where telehealth treatment may be a maximally effective and accessible treatment modality. Telehealth service may eliminate or reduce some of the practical barriers that differentially impact students of color, such as transportation concerns and available time to devote to treatment. In summary, the ICS program at MSU CAPS presents an exciting treatment possibility to students that have historically not been served in typical collegiate mental health offerings.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg – Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. We are appreciative of Michigan State University students, support staff, and administrators who created space for this program and remain dedicated to its purpose, including our colleagues at MSU CAPS. We are grateful for the services of MSU’s Center for Statistical Training and Consulting for their data analysis assistance. Thank you to the providers and staff of Colorado State University’s iTeam, who shared information and strategies with us to help develop ICS at MSU. We worked on the engine while we were in the air, and we are immensely grateful to everyone who stepped in to unequivocally stand behind what was just a dream. We acknowledge Dr. Marsha Linehan, who founded the DBT model that has helped so many, especially women and those with high treatment needs. Thank you to the Eastern and Indigenous philosophers and healers, whose wisdom was incorporated into Western medicine; we should have been listening, and we know that now. Finally, we acknowledge all those who have lost the battle with deadly mental illnesses and their loved ones. We assure you that we will return every day to fight alongside those who remain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R.-D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., Steil, R., Philipsen, A., & Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the borderline symptom list (BSL-23): Development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1159/000173701

- Brady, K. T., McCauley, J. L., & Back, S. E. (2021). The comorbidity of post-traumatic stress disorder (ptsd) and substance use disorders. In N. el-Guebaly, G. Carrà, M. Galanter, & A. M. Baldacchino (Eds.), Textbook of addiction treatment (pp. 1327–1399). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36391-8_93.

- Brunier, A., & Drysdale, C. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide: Wake-up call to all countries to step up mental health services and support. World Health Organization News Release. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide#:~:text=In%20the%20first%20year%20of,Health%20Organization%20(WHO)%20today

- Cauce, A. M., Domenech-Rodríguez, M., Paradise, M., Cochran, B. N., Shea, J. M., Srebnik, D., & Baydar, N. (2002). Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.44

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. (2022). Annual Report. Author. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://ccmh.psu.edu/annual-reports

- Chugani, C. D., Ghali, M. N., & Brunner, J. (2013). Effectiveness of short-term dialectical behavior therapy skills training in college students with cluster B personality disorders. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 27(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2013.824337

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- CSU Health Network. (n.d.). Post-Hospitalization Support (iTEAM). Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://health.colostate.edu/iteam/

- Curtin, S. (2020). State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2018. National Vital Statistics Reports, 69(11). Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr69/NVSR-69-11-508.pdf

- DeVylder, J., Zhou, S., & Oh, H. (2021). Suicide attempts among college students hospitalized for COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.058

- Dimeff, L., & Linehan, M. M. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy in a nutshell. The California Psychologist, 34(3), 10–13.

- Dubé, J. P., Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., & Stewart, S. H. (2021). Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Research, 301, 113998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113998

- Ebert, D. D., Mortier, P., Kaehlke, F., Bruffaerts, R., Baumeister, H., Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Vilagut, G., Martínez, K. U., Lochner, C., Cuijpers, P., Kuechler, A., Green, J., Hasking, P., Lapsley, C., Sampson, N. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2019). Barriers of mental health treatment utilization among first‐year college students: First cross‐national results from the WHO World mental health International college Student initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1782

- Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2012). Help seeking for mental health on college campuses: Review of evidence and next steps for research and practice. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20(4), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229.2012.712839

- Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., Speer, N., & Zivin, K. (2011). Mental health service utilization among college students in the United States. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(5), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182175123

- Eisenberg, D., Lipson, S. K., Heinze, J., & Zhou, S. (2021). The health minds study: Winter/Spring 2021 data report. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HMS_nationalwinter2021_-update1.5.21.pdf

- Elharake, J. A., Akbar, F., Malik, A. A., Gilliam, W., & Omer, S. B. (2023). Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(3), 913–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1

- Frias, A., & Palma, C. (2015). Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder: A review. Psychopathology, 48, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363145

- Gorman, K. S., Bruns, C. M., Chin, C., Fitzpatrick, N. Y., Koenig, L., LeViness, P., & Sokolowski, K. (2021). Annual survey: 2020. Association for University College Counseling Center Directors. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/Survey/2019-2020%20Annual%20Report%20FINAL%204-2021.pdf

- Gorman, K. S., Bruns, C. M., Chin, C., Fitzpatrick, N. Y., Koenig, L., LeViness, P., & Sokolowski, L. (2022). Annual Survey: 2021. Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/2020-21%20Annual%20Survey%20Report%20Public%20Survey.pdf

- Hanley, T., & Wyatt, C. (2020). A systematic review of higher education students’ experiences of engaging with online therapy. Counseling & Psychotherapy Research, 21(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12371

- Hutsebaut, J., Debbané, M., & Sharp, C. (2020). Designing a range of mentalizing interventions for young people using a clinical staging approach to borderline pathology. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-0121-4

- Janota, M., Kovess-Masfety, V., Gobin-Bourdet, C., & Husky, M. M. (2022). Use of mental health services and perceived barriers to access services among college students with suicidal ideation. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 32(3), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2022.02.003

- Kam, B., Mendoza, H., & Masuda, A. (2019). Mental health help-seeking experience and attitudes in Latina/o American, Asian American, Black American, and White American College Students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 41(4), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9365-8

- Keane, T. M., & Wolfe, J. (1990). Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder an analysis of community and clinical studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(21), 1776–1788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1990.tb01511.x

- Kelleher, I., Corcoran, P., Keeley, H., Wigman, J. T., Devlin, N., Ramsay, H., Wasserman, C., Carli, V., Sarchiapone, M., Hoven, C., Wasserman, D., & Cannon, M. (2013). Psychotic symptoms and population risk for suicide attempt: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(9), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.140

- Kleindienst, N., Jungkunz, M., & Bohus, M. (2020). A proposed severity classification of borderline symptoms using the borderline symptom list (BSL-23). Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7(11). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00126-6

- Lakens, D. (2017). Equivalence tests: A practical primer for t-tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617697177

- Lee, J., Jeong, H. J., & Kim, S. (2021). Stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 Pandemic and their use of mental health services. Innovative Higher Education, 46(5), 519–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-021-09552-y

- Lewis, S. P., Kenny, T. E., Pritchard, T. R., Labonte, L., Heath, N. L., & Whitley, R. (2022, November 1). Self-injury during COVID-19: Views from university students with lived experience. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(11), 824. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001541

- Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Lipson, S. K., Kern, A., Eisenberg, D., & Breland-Noble, A. M. (2018). Mental health disparities among college students of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014

- Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S., Abelson, S., Heinze, J., Jirsa, M., Morigney, J., Patterson, A., Singh, M., & Eisenberg, D. (2022). Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013–2021. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.038

- Lo, C., Cheng, T., & Howell, R. (2014). Access to and utilization of health services as pathway to racial disparities in serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(3), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9593-7

- Locke, B. D., Buzolitz, J. S., Lei, P.-W., Boswell, J. F., McAleavey, A. A., Sevig, T. D., Dowis, J. D., & Hayes, J. A. (2011). Development of the counseling center assessment of psychological symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021282

- Locke, B. D., McAleavey, A. A., Zhao, Y., Lei, P.-W., Hayes, J. A., Castonguay, L. G., Li, H., Tate, R., & Yu-Chu Lin, Y.-C. (2012, January 5). Development and Initial Validation of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms–34. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 45(3), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175611432642

- Masuda, A., Anderson, P. L., Twohig, M. P., Feinstein, A. B., Chou, Y.-Y., Wendell, J. W., & Stormo, A. R. (2009). Help-seeking experiences and attitudes among African American, Asian American, and European American college students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 31(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-009-9076-2

- Masuda, A., Price, M., Anderson, P. L., Schmertz, S. K., & Calamaras, M. R. (2009). The role of psychological flexibility in mental health stigma and psychological distress for the stigmatizer. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(10), 1244–1262. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.10.1244

- McAfee, N. W., Schumacher, J. A., & Kelly, C. A. (2023). Sexual and gender minority college student retention: The unique effects of mental health and campus environment on the potential for dropout. Building Healthy Academic Communities Journal, 7(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.18061/bhac.v7i1.9426

- McFarlane, W. R., Levin, B., Travis, L., Lucas, F. L., Lynch, S., Verdi, M., Williams, D., Adelsheim, S., Calkins, R., Carter, C. S., Cornblatt, B., Taylor, S. F., Auther, A. M., McFarland, B., Melton, R., Migliorati, M., Niendam, T., Ragland, J. D., … Spring, E. (2015). Clinical and functional outcomes after 2 years in the early detection and intervention for the prevention of psychosis multisite effectiveness trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(1), 30–43. PubMed: 25065017 https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu108

- Miranda, R., Soffer, A., Polanco-Roman, L., Wheeler, A., & Moore, A. (2015). Mental health treatment barriers among racial/ethnic minority versus white young adults 6 months after intake at a college counseling center. Journal of American College Health, 63(5), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1015024

- Nam, S. K., Choi, S. I., Lee, J. H., Lee, M. K., Kim, A. R., & Lee, S. M. (2013). Psychological factors in college students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029562

- National Institute of Mental Health. (1987). Towards a model for a comprehensive community-base mental health system. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration.

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2022, June). Suicide. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide

- Nieuwoudt, J. E., & Pedler, M. L. (2023). Student retention in higher education: Why students choose to remain at university. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 25(2), 326–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120985228

- Noll, L. K., Lewis, J., Zalewski, M., Martin, C. G., Roos, L., Musser, N., & Reinhardt, K. (2020). Initiating a DBT consultation team: Conceptual and practical considerations for training clinics. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000252

- Olaniyan, F.-V. (2021). Paying the widening participation penalty: Racial and ethnic minority students and mental health in British universities. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 21(1), 761–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12242

- Oliveira, P. N., & Rizvi, S. L. (2018). Phone coaching in dialectical behavior therapy: Frequency and relationship to client variables. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(5), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1437469

- Panepinto, A. R., Uschold, C. C., Olandese, M., & Linn, B. K. (2015). Beyond borderline personality disorder: Dialectical behavior therapy in a college counseling center. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 29(3), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2015.1045782

- Pistorello, J., Fruzzetti, A. E., MacLane, C., Gallop, R., & Iverson, K. M. (2012). Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 982–994. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029096

- Ratheesh, A., Hett, D., Ramain, J., Wong, E., Berk, L., Conus, P., Fristad, M. A., Goldstein, T., Hillegers, M., Jauhar, S., Kessing, L. V., Miklowitz, D. J., Murray, G., Scott, J., Tohen, M., Yatham, L. M., Young, A. H., Berk, M., & Marwaha, S. (2023). A systematic review of interventions in the early course of bipolar disorder I or II: A report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Taskforce on early intervention. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 11(1), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40345-022-00275-3 https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9t87j6m9

- Rathus, J. H., Wagner, D., & Miller, A. L. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the Life Problems Inventory, a measure of borderline personality features in adolescents. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0487.1000198

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). Telehealth for the treatment of serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Retrieved May 9, 2022, from https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-06-02-001.pdf

- Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life: Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12070

- Teater, B., Chonody, J. M., & Hannan, K. (2021). Meeting social needs and loneliness in a time of social distancing under COVID-19: A comparison among young, middle, and older adults. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 31(1–4), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1835777

- Wagner, D., Rathus, J., & Miller, A. L. (2015). Reliability and validity of the life problems inventory, a self-report measure of borderline personality features, in a college student sample. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0487.1000199

- Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e22817. https://doi.org/10.2196/22817

- Zumstein, N., & Riese, F. (2020, July 6). Defining severe and persistent mental illness-A pragmatic utility concept analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00648 Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7358610/

Appendix A

ICS inclusion & exclusion criteria used during study time period

Inclusion criteria

Initial inclusion criteria specified at least two of the following must be present:

Client is not making expected progress on treatment plan goals in current services

Lack of diagnostic clarity resulting in uncertain diagnosis and/or treatment plan

Current providers are experiencing compassion fatigue, burnout, etc.

Significant relationship difficulties between current provider(s) and patient and/or cultural considerations that have significantly impeded rapport

Client is high-risk to the extent that treatment is disrupted by persistent safety planning, hospitalization, etc. and/or the student is “noncompliant: or “resistant.”

Exclusion criteria

The referral form included exclusion criteria, which were provided to determine appropriate level of care and guide collaborative care:

Lack of consultation with the client about the referral and at least verbal consent obtained

Lack of consultation with collaborating treatment providers

Severe and active psychosis

Severe and untreated ADHD

Autism spectrum disorder resulting in moderate to severe functional impairment

Major neurocognitive disorder and/or any diagnosis or functional level such that client was unable to retain information verbally or behaviorally participate in groups, and/or benefit from intensive mental health outpatient care

Edits and additions to these inclusion and exclusion criteria continue to be made to better serve high-risk students.

Appendix B

Extended Intensive Clinical Services (ICS) treatment services/providers description

Weekly DBT-Informed individual psychotherapy characteristics

Provided by fully licensed ICS providers, including social workers and psychologists, as well as doctoral trainees

Weekly diary card completion with collaboratively created client-specific diary card

Inclusion of behavior chain analyzes

Culturally inclusive interventions

Relevant culturally norms incorporated into skilled behavior component of behavior chain analyses (e.g., ancestral rites, pastoral consultation)

Recognition of environmental invalidation present in dominant culture (e.g., Eurocentrism, homophobia, racism)

Weekly DBT-Informed group psychotherapy characteristics

Facilitated by a licensed masters or doctoral level staff member and a trainee at the masters, doctoral, or residency level across psychology, counseling, social work, and psychiatry disciplines

90-minutes in duration with two to three groups offered per semester

Open to all university students rather than exclusive to those engaged in ICS

Four modules of DBT

Two weeks of mindfulness skills

Five weeks of distress tolerance skills

Seven weeks of emotion regulation skills

Four weeks of interpersonal effectiveness skills

Occasional adaptations of skills to support cultural sensitivity (e.g., women and patients of color may receive different responses compared with men when utilizing interpersonal effectiveness skills that emphasize assertiveness)

Additional groups offered at CAPS or in the community available to ICS participants (e.g., CAPS’ African American Women’s Group, NAMI Peer-to-Peer)

Consultation/Treatment team meeting characteristics

Composed of relevant treatment providers

Typically one to two weekly meetings involving individual program service providers (i.e., psychology, psychiatry, nursing, trainees)

One to two meetings involving individual and crisis service providers (i.e., crisis services covered program and general student services; see crisis services section for more information on breadth of services)

One meeting involving group service providers (i.e., staff and trainee facilitators)

Crisis service characteristics

Licensed ICS clinical staff provided crisis walk-in services to support safety and crisis management

ICS staff assistance with hospitalizations, post-hospitalization appointments, means restriction and disposal, phone call follow ups for after-hours crisis services, and critical incident response across campus

Provision of supplementary risk management appointments to clients served in general counseling

Phone coaching typical of DBT treatment programs (see Oliveira & Rizvi, Citation2018) not offered in ICS

ICS clients initially provided with a script explaining to crisis line providers that they are participating in DBT-informed treatment and need assistance putting their skills into use.

University contracted with specialized crisis line service provider, which permitted ICS provider follow up with all crisis line contacts

Care management service characteristics

Provided by limited license provider holding bachelor of social work degree and provided by Licensed ICS clinical staff.

Goal of service was to address environmental variables impacting a client’s overall wellness and support patient through advocacy as needed

Provided service connections in areas, such as food/nutrition assistance, housing, utilities, transportation, health insurance, sexual wellness resources, technology resources, general financial resources, legal system/resources, immigration/visas, and navigation of academic services/processes.

Provided advocacy letters to students in areas related to receiving gender affirming healthcare, academic accommodations in partnership with the Michigan State University Resources for Persons with Disabilities, and coordination of care summaries with psychiatric providers in the community.

Psychiatric services characteristics

Services provided by psychiatry providers at CAPS or community-based providers

Communication among psychiatry and therapy, case management ICS service providers to facilitate integrated care model

Supporting service characteristics

Utilization of university or community-based health services to address the holistic needs of ICS participants (e.g., primary care nurse practitioners involved in a client’s care due to client’s chronic physical health conditions impacting treatment attendance)

Option to include family/supportive others in ICS treatment (e.g., safety planning assistance, psychoeducation)

Limited psychological assessment for differential diagnosis provided by doctoral trainees under the supervision of fully licensed psychologist