Abstract

Peer assisted learning (PAL) is well documented in the medical education literature. In this paper, the authors explored the role of PAL in a graduate entry medical program with respect to the development of professional identity. The paper draws on several publications of PAL from one medical school, but here uses the theoretical notion of legitimate peripheral participation in a medical school community of practice to shed light on learning through participation. As medical educators, the authors were particularly interested in the development of educational expertise in medical students, and the social constructs that facilitate this academic development.

Introduction

Peer assisted learning (PAL) has been described as, “People from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching.”Citation1 PAL is well accepted as an educational method in many medical curricula, where participation and learning involves a process of socialization. During PAL activities, peers are dependent on each other’s relevant experiences and shared resources, and knowledge may be socially rather than individually constructed.Citation2 Within medical schools, PAL provides a framework within which students can practice and improve their medical and teaching skills,Citation3 helping to shape students’ professional values as they move into medical practice. This paper outlines the PAL activities in a medical school, views them through a theoretical lens of the medical school as a community of practice, and then focuses on the impact of PAL on students’ professional identity, with a special interest in their educational expertise.

Theoretical notions of communities of practice

The theoretical notion of communities of practice is frequently cited in the health profession’s education literature.Citation4 Evolving from ethnographic studies of apprenticeships, it has been appropriated from its original context into clinical education.Citation5 Fundamental to communities of practice is the notion that learning occurs through participation in activities important to the community. Newcomers are provided with meaningful and manageable tasks that contribute to the product of the community, that is, through legitimate peripheral participation.Citation6 Participation enables newcomers to familiarize themselves with the language, tasks, processes, and organizing principles of the community, progressively becoming more central with increasing levels of responsibility. During this process, the participant develops an identity as a member of the community.Citation6 Two important concepts influence legitimate peripheral participation. One relates to the “agency” of the individual, that is, the willingness of the individual to participate. The second relates to the “affordances” of the workplace, that is, the invitational quality of the “community.”

PAL in a medical school community of practice

Medical schools are communities of practice with goals different to the clinical settings in which students will eventually work. The authors posit that the PAL activities in this medical school provided students with legitimate peripheral participation by enabling them to take on teaching and assessment roles. Participation in these activities simultaneously developed new “professional” skills (educational expertise) while creating and consolidating medical knowledge and skills. The combination of this learning facilitated the development of students’ emerging identities as junior doctors. This all took place in the relative “safety” of the medical school community of practice.

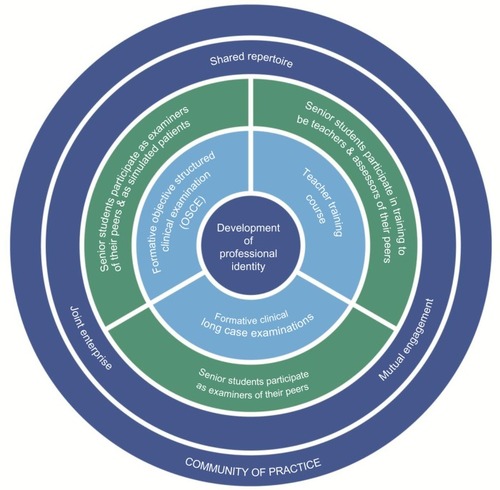

PAL at the Sydney Medical School consists of three activities, as illustrated in : teacher training course, formative long case clinical examinations, and formative objective structured clinical examination (OSCE).

Figure 1 Peer assisted learning program at Sydney Medical School – Central as a community of practice.

Teacher training course

The “Teaching on the Run” course is delivered as a six-module program over 18 hours. It provides theoretical background, practical examples, and active participation for medical students in a range of activities, including skills teaching, assessment, and training in the delivery of effective feedback in the clinical context.Citation7

Formative long case clinical examinations

The long case examination requires students to undertake an unobserved physical examination and history taking of a patient for 1 hour; then, students are assessed for 20 minutes by two academic examiners on their presentation. In this formative version, students are required to act as an assessor of their peers, alongside an academic examiner. These examinations are designed to inform the students of their strengths and weaknesses in preparation for summative examinations.Citation8

Formative objective structured clinical examination

The OSCEs require students to be examined at five stations, each assessing communication, examination, or procedural skills. In the formative OSCE, senior students assess junior students while other students act as simulated patients, that is, role playing as patients.Citation9,Citation10

Discussion

The impact of PAL on the school community

Participation in PAL consisted of voluntary and compulsory student activities. However, the focus on alignment of PAL with assessment made participation very attractive. Students had a common interest in studying medicine and were actively taking part in a model of learning at several levels and with academic staff. This collaborative, dynamic interplay helped to develop a social learning network. The teacher training course provided a foundation for the PAL activities, with students claiming that the academic facilitators were “fostering a changing culture.”Citation7 Voluntary participation in the teacher training course almost doubled over 3 years (32%–57%) and similarly in the formative OSCEs (25%–41%). Although participation in the formative long case examinations was compulsory, students valued highly the opportunity to engage with academic staff as colleagues.

As PAL participation increased, a supportive and professional culture evolved within the student community. Students were not only taking part to reinforce their own medical knowledge, but saw participation as a way to “support other students” and provide feedback and “tips” based on what they had learnt from their “own exams,” and develop their own teaching and assessment skills, an element of educational expertise.Citation9 The student body’s joint enterprise, mutual engagement, and shared repertoireCitation11 in the PAL activities enriched the social capital of the clinical school. The program was awarded the University Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Support of the Student Experience.Citation12

Identity-based curriculum

Medical students have many different roles within and across their clinical school, their medical faculty, university, and beyond, and so a focus on professional identity formation is relevant in contemporary medical curricula.Citation13 PAL emphasizes the professional expectations of the students as medical graduates. Teaching, assessment, and communication skills are increasingly recognized internationally by universities and medical councils as requisite graduate competences.Citation14 PAL has enabled these expectations to be met by providing students with opportunities to learn, understand, and develop these skills. Senior students undertake meaningful educational tasks that they must train and prepare for, mirroring the roles they will assume as junior medical staff.Citation9 By participating in PAL, students recognize the importance of these skills within medicine and associate these attributes with their identity as medical students and future medical practitioners, helping to foster a life-long culture of teaching.Citation14

Development of professional relationships

Although most medical programs are now vertically integrated with early clinical exposure, limited faculty availability for teaching is well recognized as a problem within medical education.Citation15,Citation16 The PAL activities facilitated senior students’ interaction with senior academics. Students had role models close at hand, and felt privileged to be in such a position. Academic staff treated the students as colleagues,Citation17 reinforcing students’ identity as valuable members of the school community.

Inclusive activities

Medical education can be viewed as a process of socialization, which helps to redefine the task of medical educators.Citation18 The social context of the PAL activities induced communal engagement, shaping the culture of the learning environment.Citation17 The interactions of junior and senior students, sharing their expertise within a contextual clinical framework, prompted collaborative student engagement. Although junior students are on the boundaries of the school’s community of practice, they are important participants. The first years of medical school can be socially isolating for students, but PAL activities facilitate junior and senior student exchange in a formal, professional context. At the same time, the PAL process helps to establish the professional identity of senior students who are expected to have enough medical knowledge and professionalism skills to act as assessors and formulate peer feedback. Although not given the scope to practice their own teaching and assessment skills, junior students develop an appreciation of their own future role and responsibilities as senior members of the student community.

Proficiency and responsibilities of students

In PAL, order, engagement, and commitment from participants are achieved through careful planning and preparation.Citation19 Student assessors were required to attend training sessions and prepare for the activities. Students became familiar with the resources, assessment methods, marking domains, marking criteria, and feedback techniques. By allowing students to assess their peers in the formative OSCEs and long cases, their responsibilities were aligned with their abilities, and competence was developed.Citation19 Students become active participants in the development of their own professional identity.

Conclusion

This paper reflected on PAL practices within a medical school, exploring students’ academic development through social constructs. The PAL program acts as a dynamic tool in shaping the school’s community of practice, positively impacting its culture, and adding to its social capital. Participation in PAL helps students to establish their professional identity and recognize their significant roles and responsibilities as medical students and their future roles as medical practitioners with teaching, assessment, and life-long learning responsibilities.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ToppingKJThe effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: a typology and review of the literatureHigher Education1996323321345

- SwanwickTInformal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to “culturism”Med Educ200539885986516048629

- BardachNSVedanthanRHaberRJ“Teaching to teach”: enhancing fourth year medical students’ teaching skillsMed Educ200337111031103214629425

- LiLCGrimshawJNielsenCJuddMCoytePCGrahamIDUse of communities of practice in business and health care sectors: a systematic reviewImplement Sci200942719445723

- MorrisCReplacing “the firm”: re-imagining clinical placements as time spent in communities of practiceCookVDalyCNewmanMWork Based Learning in Clinical Settings – Insights from Socio-Cultural PerspectivesOxfordRadcliffe Medical20121125

- LaveJWengerESituated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation1st edCambridgeCambridge University Press1991

- BurgessABlackKChapmanRClarkTRobertsCMellisCClinical teaching skills for students: our future educatorsClin Teach20129531231622994470

- BurgessARobertsCBlackKMellisCSenior medical student perceived ability and experience in giving feedback in formative long case examinationsBMC Med Educ2013137923725417

- BurgessAClarkTChapmanRMellisCSenior medical students as peer examiners in an OSCEMed Teach2013351586223102164

- BurgessAClarkTChapmanRMellisCMedical student experience as simulated patients in the OSCEClin Teach20131024625023834571

- WengerECommunities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and IdentityCambridgeCambridge University Press1998

- 2013 vice-chancellor award winners [webpage on the Internet]SydneyThe University of Sydney2013 [cited July 5, 2013]. Available from: http://www.itl.usyd.edu.au/awards/2013_awardwinners.htmAccessed March 6, 2014

- YuTCWilsonNCSinghPPLemanuDPHawkenSJHillAGMedical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical schoolAdv Med Educ Pract2011215717223745087

- CookeMIrbyDMO’BrienBCEducating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and ResidencySan Francisco, CAJossey-Bass2010

- DahlstromJDorai-RajAMcGillDOwenCTymmsKWatsonDAWhat motivates senior clinicians to teach medical students?BMC Med Educ200552716022738

- MehtaNBHullALYoungJBStollerJKJust imagine: new paradigms for medical educationAcad Med201388101418142323969368

- SchumacherDJEnglanderRCarraccioCDeveloping the master learner: applying learning theory to the learner, the teacher, and the learning environmentAcad Med201388111635164524072107

- DornanTBundyCWhat can experience add to early medical education? Consensus surveyBMJ2014329747083415472265

- FraserSWGreenhalghTCoping with complexity: educating for capabilityBMJ2001323731679980311588088