Abstract

Introduction

Eighty percent of COPD patients experience dyspnea during activities of daily life (ADL). To the best of our knowledge, the Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) dyspnea scale is the only validated scale designed to quantify dyspnea during ADL available in the French language. Two other instruments are only available in English versions: the London Chest Activity of Daily Living (LCADL) scale that allows a specific evaluation of dyspnea during ADL and the Dyspnea-12 questionnaire that evaluates the affective (emotional) and sensory components of dyspnea in daily life. The aim of this study was to translate and validate French versions of both LCADL and Dyspnea-12 questionnaires and to determine the reliability of these versions for the evaluation of dyspnea in severe to very severe COPD patients.

Methods

Both translation and cultural adaptation were based on Beaton’s recommendations. Fifty consecutive patients completed the French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 and other questionnaires (MMRC, Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ], Hospital Anxiety and Depression [HAD]), at a 2-week interval. Internal consistency, validity, and reliability of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 were evaluated.

Results

The French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α of, respectively, 0.84 and 0.91. LCADL was correlated significantly with item activity of SGRQ (ρ=0.55, p<0.001), total score of SGRQ (ρ=0.63, p<0.001), item impact of SGRQ (ρ=0.57, p<0.001), and HAD-depression (HAD-D) (ρ=0.47, p=0.001); and Dyspnea-12 was correlated significantly with MMRC (ρ=0.39, p<0.001), HAD-anxiety (ρ=0.64, p<0.001), and HAD-D (ρ=0.64, p<0.001). The French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 demonstrated good test–retest reliability with, respectively, intraclass coefficient =0.84 (p<0.001) and 0.91 (p<0.001).

Conclusion

The French versions of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 questionnaires are promising tools to evaluate dyspnea in severe to very severe COPD patients.

Introduction

COPD is characterized by a permanent and progressive obstruction of airways, inflammation, and systemic manifestations.Citation1 During COPD progression, muscle, cardiovascular, psychological, nutritional, bone, or neurological impairments may appear.Citation2 Breathlessness, the main symptom presented by COPD patients,Citation3 results from bronchial and parenchyma alterations and peripheral muscle changes, all alterations that contribute dramatically to the disability of COPD patients.Citation3,Citation4

Activities of daily life (ADL) are defined as all movements performed every day by a person with the aim of taking care of himself/herself for participation in social life.Citation5,Citation6 COPD patients report important difficulties during ADL. In a study of Polatlı et al,Citation7 the vast majority of COPD patients interviewed mentioned a negative impact of their disease on their ADL. Garrod et alCitation8 showed that ~80% of COPD patients interviewed experienced dyspnea during ADL. The most frequently altered ADL are walking and getting upstairs, followed by sexual activity, domestic tasks, and personal care.Citation7,Citation9,Citation10 Dyspnea and fatigue are the main causes of these limitations, particularly in ADL involving upper limbs.Citation4 To the best of our knowledge, the Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) scale is the only validated scale in French language to evaluate the functional status of dyspnea in ADL.Citation11 However, this scale is moderately sensitive to changes and explores a limited part of ADL (mainly walking). The London Chest Activity of Daily Living (LCADL) scale allows evaluating dyspnea in the current ADL performed by patients. The Dyspnea-12 questionnaireCitation12 allows evaluating the affective (emotional) and sensory components of dyspnea. In COPD patients, Garrod et al and Yorke et al showed that LCADLCitation8,Citation13 and Dyspnea-12 were valid and reliable questionnaires.Citation12,Citation14 Moreover, LCADL was responsive to improvement following pulmonary rehabilitation. While LCADL was developed in EnglishCitation8 and was translated and validated in Portuguese and Spanish,Citation15–Citation17 there is no translated and validated version in French language. Similarly, Dyspnea-12 questionnaire is only validated in English.Citation12

The aim of this study was thus to develop and to validate a French version of both LCADL and Dyspnea-12 questionnaires and to assess the reliability of these versions for the evaluation of dyspnea in severe and very severe COPD patients.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the local ethic board (CPP Ouest 6 – CPP 886 – Soins courants; RCB: 2015-A00631-48) on June 2015 and registered (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT2555202). All patients provided written informed consent.

Procedure

Translation and cultural adaptation were based on Beaton’s recommendations.Citation18 Initial translation was realized independently by two native French speakers (FC and MB), with permission to translate and use the questionnaires obtained from the authors of the original versions. A synthesis of the two translations was realized to end in a common version. The translation return (from French toward English) was performed by an independent English native speaker (SN), unaware of the original questionnaires, in order to check accuracy.

A version of each translation was tried and discussed with 10 patients to raise concerns about whether the sentences used were understood. Patients found them comprehensible completing both questionnaires and no patient hadany queries about the sentences used in these two translations. This final version was thus used in the present study (Supplementary materials).

Protocol

To test the validity and reliability of both questionnaires, we only used the instruments which were used for the development of each questionnaire.Citation13,Citation14,Citation19

Validity

Internal consistency and validity of the French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 were estimated at the time COPD patients paid their annual visit to the outpatient clinic.

For LCADL, the primary end point was the correlation of LCADL with activity’s score of Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), as it was used for the original validation of LCADL.Citation8 Secondary end points were the correlation of LCADL with the total score of SGRQ, impact’s score of SGRQ, MMRC scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale – item anxiety (HAD-A) and item depression (HAD-D), as it was used for the original validation of LCADL.

For Dyspnea-12, the primary end point was the correlation of Dyspnea-12 with MMRC scaleCitation12 as it was used for the original validation of Dyspnea-12. Secondary end points were the comparison of Dyspnea-12 with HAD scale – item anxiety and item depression, FEV1, as it was used for the original validation of Dyspnea-12.

Reliability

Reliability of the French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 was estimated by the method of test–retest over a period of 15 days. Patients filled in LCADL and Dyspnea-12 questionnaires and the other questionnaires (MMRC, SGRQ, and HAD) during outpatient clinic visits. Participants were provided with a copy of all questionnaires and were asked to fill them all out 15 days later at home and to mail them back.

LCADL scale

This 15-item, self-administered questionnaire has been developed by Garrod et al.Citation19 It allows an evaluation of dyspnea in patients with COPD during daily activities divided into four components: self-care, domestic, physical, and leisure. Patients could score from 0: “I would not do anyway” to 5: “I need someone else to do this”. LCADL score is calculated by aggregating the points assigned to each question, with a higher score representing maximal disability.

Dyspnea-12

This 12-item self-administered questionnaireCitation12,Citation14 measures dyspnea severity in both its physical and affective components, independently from activity limitation. Patients score ranges from “none” (corresponding to score 0) to “severe” (score 3). Dyspnea-12 score is calculated by aggregating the points assigned to each question; the higher the score, the greater the severity.

SGRQ

SGRQ is a reliable measure of health status in COPD patientsCitation20 and has been validated in French language.Citation21 It is sensitive to changes in health status over timeCitation22 and a minimal clinical important difference (MCID) has been proposed.Citation23,Citation24 SGRQ consists of 50 items with four scores: symptoms, activity, psychosocial impact, and a total score. The highest score at 100 represents the maximal negative impact of COPD on quality of life.

MMRC dyspnea scale

MMRC dyspnea scale is the first self-administered scale which assesses the impact of dyspnea on ADL.Citation25 It consists of five grades increasing in severity of chronic respiratory diseaseCitation11 from “I only get breathless with strenuous exercise” to “I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing or undressing.”

HAD scale

It is a validated self-administered scale used for assessing psychological distress. It was validated in French language.Citation26 It consists of 14 items, seven for evaluating anxiety and seven for depression, with a score ranging from 0 to 21 for each domain. HAD-anxiety or HAD-depression score ≥11Citation27,Citation28 suggests significant anxiety or depression. A MCID has been proposed.Citation29

Study population

All COPD patients attending the outpatient clinic for their annual follow-up in the pulmonology unit of Morlaix Hospital Centre were eligible for the study if they were diagnosed with severe or very severe COPD, according to Global initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guideline’s criteria,Citation30 and able to complete questionnaires in French language. Exclusion criteria were COPD exacerbation in the previous month or during the 15 days following inclusion, and absence of written informed consent. To assess stability of the disease, we questioned patients about acute exacerbation between test and retest.

Sample size

For the analysis of reliability, according to Walter et al,Citation31 by considering an intraclass coefficient (ICC) of 0.8 as being acceptable, 46 subjects were required. Taking into account a 10% proportion of unreturned questionnaires, the total sample size was set to 50 patients.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed for demographic parameters and for questionnaires results. The internal consistency of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient. The validity of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 was measured using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation between, respectively, the score of the French version of LCADL and item activity’s score of SGRQ, total score of SGRQ, item impact’s score of SGRQ, MMRC scale, and HAD scale; and the score of the French version of Dyspnea-12 and MMRC scale, HAD scale, and FEV1.

Floor and ceiling effects were verified if at least 15% of participants reached the lowest or the highest score, respectively. The test–retest reliability was evaluated using ICC for agreement and agreement was estimated using Bland–Altman method.

All tests were two-tailed, with a statistical significance level fixed at a p-value of 0.05. The data were computed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

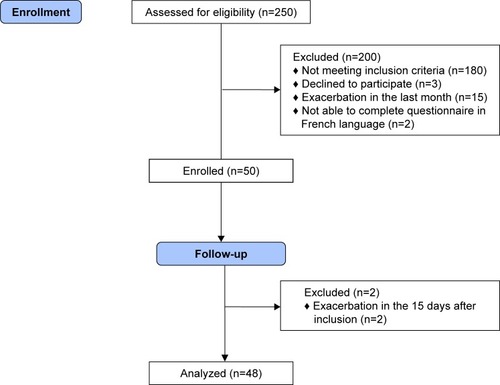

Fifty consecutive patients met the inclusion criteria and completed the French version of LCADL and Dyspnea-12, and the others questionnaires (MMRC, SGRQ, and HAD) (). Two patients were excluded because they had acute exacerbation in the 15 days following inclusion. Forty-eight patients completed the second set of questionnaires for the test–retest assessment. Demographic items, clinical data, and initial results of the questionnaires are reported in .

Table 1 Baseline patient characteristics and values of initial questionnaires

LCADL

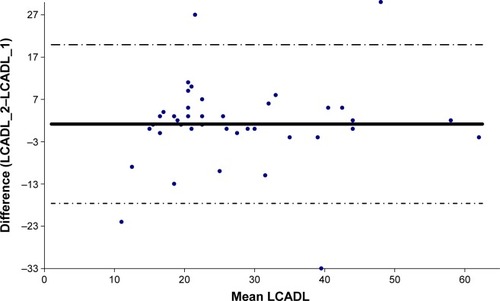

The French version of LCADL demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.84) and good test–retest reliability (ICC=0.84 [95% CI 0.72–0.91], p<0.001) ().

Figure 2 Bland–Altman plot of total score of LCADL.

Abbreviations: LCADL, London Chest Activity of Daily Living questionnaire; LCADL_1, LCADL filled out at the first consultation; LCADL_2, LCADL filled out 15 days later.

LCADL score was significantly correlated with activity’s score of SGRQ (ρ=0.55, p<0.001), total score of SGRQ (ρ=0.63, p<0.001), impact’s score of SGRQ (ρ=0.57, p<0.001), HAD-D (ρ=0.47, p=0.001), but not with MMRC (ρ=0.28, p=0.05) nor with HAD-A (ρ=0.24, p=0.09).

Dyspnea-12

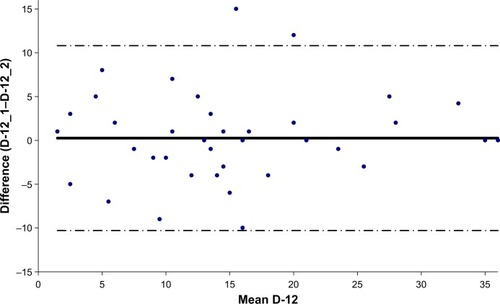

The French version of Dyspnea-12 demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.91) and good test–retest reliability (ICC=0.91 [95% CI 0.84–0.95], p<0.001) ().

Figure 3 Bland–Altman plot of total score of Dyspnea-12.

Abbreviations: D-12, Dyspnea-12; D-12_1, Dyspnea-12 filled out at the first consultation; D-12_2, Dyspnea-12 filled out 15 days later.

It was significantly correlated with MMRC (ρ=0.39, p<0.001), HAD-A (ρ=0.64, p<0.001), HAD-D (ρ=0.64, p<0.001), but not with FEV1 (ρ=−0.22, p=0.13). The analysis of the scores distribution in our patients’ population revealed an absence of ceiling and floor effects for LCADL and Dyspnea-12 with <3% of patients having the lowest or highest scores.

Discussion

This study shows good validity and internal consistency for both French versions of LCADL and Dyspnea-12. The test–retest reliability was verified for the translated versions of both questionnaires. These results contribute to a proper validation of our French version of these two instruments in severe or very severe COPD patients.

The results of the primary end points (SGRQ item activity for LCADL and MMRC for Dyspnea-12) obtained in our study are in agreement with the initial validation of both questionnaires LCADL and Dyspnea-12. For LCADL, the value of correlation with quality of life, assessed by means of the SGRQ, is lower than that observed in the original English validation. The fact that dyspnea is not the sole cause of alteration of quality of life in COPD can partly explain these findings.

For the secondary end points, some differences appeared in our study: LCADL was neither correlated with MMRC nor with HAD-A and Dyspnea-12 was not correlated with FEV1. As regards MMRC, the correlation failed to reach statistical significance, as was the case for the validation of the Spanish version.Citation17 MMRC is widely used in clinical care but might be less discriminating than LCADL. Indeed, LCADL explores more situations than MMRC and that can explain the lack of correlation between these scales. As regards HAD, Garrod et alCitation8 reported a significant correlation between LCADL and HAD-A but not with HAD-D. In our study, we found the opposite – a significant correlation between LCADL and HAD-D but not with HAD-A. Our patients had more severe disease according to GOLD and were younger than those studied by Garrod et al. Prevalence of depression increases with increasing COPD severity.Citation32 Conversely, anxiety is more in older adults.Citation33 These trends can explain differences between our results and those of Garrod et al.

For Dyspnea-12, we found no correlation with FEV1; in our study, we included only severe or very severe COPD patients and that can explain this absence of correlation. Earlier studies on this topic found conflicting results.Citation34–Citation38 Indeed, a lot of patients can present moderate COPD and very high disability. In contrast, patients with severe COPD can too exhibit moderate disability.

The results of this study have a clinical impact for French speaking COPD patients, which represent a large population. Dyspnea is the major symptom reported by COPD patientsCitation39,Citation40 and the main reason for referral. Recent advances in the knowledge on the mechanisms of dyspneaCitation41 highlight the interest of an evaluation that takes into account three domains:Citation42 sensory or physical, affective, and impact.Citation43 This complete evaluation gives more information and allows a better understanding of the causes and mechanisms of dyspnea, in the aim to treat it optimally. This is clearly mentioned in the American Thoracic Society statement about update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea.Citation43

French validation of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 enables evaluating the impact of dyspnea and measuring sensory and affective components of dyspnea in daily living, respectively. With the recent validation of the multidimensional dyspnea profile,Citation44 French respiratory caregivers and researchers can handle different tools enabling an indepth evaluation of dyspnea.

Our study had some limitations: first, we only included severe or very severe COPD patients from a single center to validate the Dyspnea-12 scale. Second, it could also be interesting to make use of the coefficient of determination (r2) that might be more useful to assess the degree of variation in one score, as is explained by the other.Citation45 The choice of Pearson’s r in our study was driven for use for the original validation of Dyspnea-12.

In conclusion, the French versions of LCADL and Dyspnea-12 are valid and reproducible to evaluate dyspnea in severe or very severe COPD patients.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Society Orkyn for the financial support and especially Mrs Nadine Morel (Orkyn) for her help. We thank Miss Swathi Narayan for the translation of the questionnaires. We thank Pr Leroyer for help with the English language.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DecramerMJanssensWMiravitllesMChronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet201237998231341135122314182

- DecramerMJanssensWChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbiditiesLancet Respir Med201311738324321806

- RiesALImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life: the role of dyspneaAm J Med200611910 Suppl 1122016996895

- JolleyCJMoxhamJA physiological model of patient-reported breathlessness during daily activities in COPDEur Respir Rev200918112667920956127

- BlouinMDictionnaire de la réadaptationVolume 2QuebecGouvernement du Quebec1995

- VellosoMJardimJRFunctionality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: energy conservation techniquesJ Bras Pneumol200632658058617435910

- PolatlıMBilginCŞaylanBA cross sectional observational study on the influence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on activities of daily living: the COPD-life studyTuberk Toraks201260111222554361

- GarrodRBestallJPaulEWedzichaJJonesPDevelopment and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe COPD: the London chest activity of daily living scale (LCADL)Respir Med200094658959610921765

- KatzPPGregorichSEisnerMDisability in valued life activities among individuals with COPD and other respiratory conditionsJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev201030212613619952768

- AnnegarnJMeijerKPassosVLProblematic activities of daily life are weakly associated with clinical characteristics in COPDJ Am Med Dir Assoc201213328429021450242

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- YorkeJMoosaviSHShuldhamCJonesPWQuantification of dyspnea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnea-12Thorax2010651212619996336

- GarrodRDevelopment and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the London chest activity of daily living scaleJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2001213178

- YorkeJSwigrisJRussellAMDyspnea-12 is a valid and reliable measure of breathlessness in patients with interstitial lung diseaseChest2011139115916420595454

- PittaFProbstVSKovelisDValidação da versão em português da escala London Chest Activity of Daily Living (LCADL) em doentes com doença pulmonar obstrutiva crónicaRev Port Pneumol2008141274718265916

- CarpesMFMayerAFSimonKMJardimJRGarrodRVersão brasileira da escala London Chest Activity of Daily Living para uso em pacientes com doença pulmonar obstrutiva crônicaJ Bras Pneumol200834314315118392462

- VilaroJGimenoESanchezNActividades de la vida diaria en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica: validación de la traducción española y análisis comparativo de 2 cuestionariosMed Clin (Barc)2007129932633217910846

- BeatonDEBombardierCGuilleminFFerrazMBGuidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measuresSpine (Phila Pa 1976)200025243186319111124735

- GarrodRPaulEAWedzichaJAAn evaluation of the reliability and sensitivity of the London chest activity of daily living scale (LCADL)Respir Med200296972573012243319

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMThe St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireRespir Med199185Suppl 225311759018

- BouchetCGuilleminFOriginalAValidation du questionnaire St Georges pour mesurer la qualité de vie chez les insuffisants respiratoires chroniquesRev Mal Respir199613143468650415

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation: the St. George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- JonesPWSt. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCIDCOPD200521757917136966

- WellingJBAHartmanJETen HackenNHTKloosterKSlebosD-JThe minimal important difference for the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe COPDEur Respir J20154661598160426493797

- MahlerDAWellsCKEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- LepineJPGodchauMBrunPAnxiety and depression in inpatientsLancet19853268469–847014251426

- SPLFRecommandation pour la pratique clinique. Prise en charge de la BPCO, mise à jour 2009Rev Mal Respir201027552254820569889

- SnaithRPThe Hospital Anxiety and Depression ScaleHealth Qual Life Outcomes200312912914662

- PuhanMAFreyMBüchiSSchünemannHJThe minimal important difference of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Qual Life Outcomes200864618597689

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- WalterSDEliasziwMDonnerASample size and optimal designs for reliability studiesStat Med19981711011109463853

- LacasseYRousseauLMaltaisFPrevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2001212808611314288

- DebASambamoorthiUDepression treatment patterns among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and depressionCurr Med Res Opin201733220120827733085

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMAProbstVSDecramerMGosselinkRCharacteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171997297715665324

- LareauSCMeekPMRoosPDevelopment and testing of the modified version of the Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire (PFSDQ-M)Heart Lung19982731591689622402

- BelzaBSteeleBHunzikerJLakshminaryanSHoltLBuchnerDCorrelates of physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseNurs Res200150419520211480528

- BendstrupKEIngemann JensenJHolmSBengtssonBOut-patient rehabilitation improves activities of daily living, quality of life and exercise tolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J19971012280128069493664

- Garcia-AymerichJFélezMAEscarrabillJPhysical activity and its determinants in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Sci Sports Exerc200436101667167315595285

- SergyselsRQuestion 3-1. L’évaluation fonctionnelle de reposRev Mal Respir2005222023

- KroenkeKArringtonMEMangelsdorffADThe prevalence of symptoms in medical outpatients and the adequacy of therapyArch Intern Med19901508168516892383163

- DangersLMorelot-PanziniCSchmidtMDemouleAMécanismes neurophysiologiques de la dyspnée: de la perception à la cliniqueRéanimation2014234392401

- LansingRWGracelyRHBanzettRBThe multiple dimensions of dyspnea: review and hypothesesRespir Physiol Neurobiol20091671536018706531

- ParshallMBSchwartzsteinRMAdamsLAn official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspneaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185443545322336677

- BanzettRBO’DonnellCRGuilfoyleTEMultidimensional dyspnea profile: an instrument for clinical and laboratory researchEur Respir J20154561681169125792641

- WilliamsMTJohnDFrithPComparison of the Dyspnoea-12 and multidimensional dyspnoea profile in people with COPDEur Respir J2017493160077328182565