Abstract

Medication-overuse headache (MOH) is a worldwide health problem with a prevalence of 1%–2%. It is a severe form of headache where the patients often have a long history of headache and of unsuccessful treatments. MOH is characterized by chronic headache and overuse of different headache medications. Through the years, withdrawal of the overused medication has been recognized as the treatment of choice. However, currently, there is no clear consensus regarding the optimal strategy for management of MOH. Treatment approaches are based on expert opinion rather than scientific evidence. This review focuses on aspects of epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of MOH. We suggest that information and education about the risk of MOH is important since the condition is preventable. Most patients experience reduction of headache days and intensity after successful treatment. The first step in the treatment of MOH should be carried out in primary care and focus primarily on withdrawal, leaving prophylactic medication to those who do not manage primary detoxification. For most patients, a general practitioner can perform the follow-up after detoxification. More complicated cases should be referred to neurologists and headache clinics. Patients suffering with MOH have much to gain by an earlier treatment-focused approach, since the condition is both preventable and treatable.

Introduction

Headache disorders are a major public health concern given their high prevalence and the large amount of associated disability and financial costs to both the individual and society.Citation1–Citation4 According to the Global Burden of Disease Study from 2010, headache is among the top ten causes of disability measured as years of life lost to disability (YLDs).Citation4

Headache usually occurs episodically, but 2%–5% of the general population have headache on ≥15 days per month, defined as chronic headache.Citation5–Citation9 Patients with chronic headache represent a large population in primary care and neurology settings.Citation10–Citation12 Headache is usually treated with analgesics, and is probably the most common reason for use of analgesics in the general population.Citation13–Citation17 Studies have identified 20%–40% of the general population to use analgesics over the previous 14 days.Citation15,Citation16,Citation18 In Denmark, sales figures of over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics were extrapolated to correspond to almost 8% of the general population taking the highest recommended daily dose every day for a whole year.Citation19

Too much use of symptomatic medication for headaches may lead to medication-overuse headache (MOH).Citation9 This is a condition characterized by chronic headache and overuse of different acute headache medications. Withdrawal headache after overuse of ergotamine was described in the early 1950s, and since the 1980s, studies have shown that frequent intake of symptomatic headache medication may transform episodic headache to chronic headache.Citation20–Citation25

The treatment of MOH is often complex and withdrawal of the overused medication is recognized as the treatment of choice.Citation26 Although several reviews on MOH have already been published,Citation27–Citation31 this review attempts to give an update on different aspects of MOH.

Classification of headache disorders and MOH

Headache is a subjective symptom, and no laboratory tests or other objective tests are available to diagnose headache. Classification and diagnostic criteria are therefore of essential importance both in clinical practice and research settings. Until 1960, headache diagnoses and studies were based on nonuniform descriptions of symptomatology. Diagnostic criteria for headache were first presented in 1962 when an ad hoc committee of the National Institutes of Health published a first set of criteria.Citation32 In 1988, the International Headache Society (IHS) published a classification system that became the standard for headache diagnosis: Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain.Citation33 In the 1988 edition, the diagnosis “headache induced by chronic substance use or exposure” was taken into the classification. In 2004, a second edition “The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II)” was published, and the term “medication-overuse headache” was introduced.Citation34 To be more applicable to patients in clinical practice, the diagnostic criteria for MOH were revised twice for the ICHD-II.Citation35–Citation37 Before the last revision, MOH should paradoxically be entitled as “probable MOH” until overuse was discontinued, and then, if the patient improved after detoxification, given a definite MOH diagnosis. This meant that the patient could not receive a definite diagnosis of MOH until after a successful withdrawal of medication, following which she/he would no longer have MOH.

In 2013, a new version, “The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd beta edition (ICHD-IIIb)”, was published, taking these changes to MOH into account.Citation9

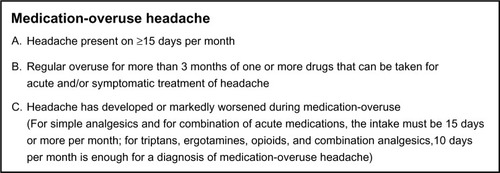

According to the ICHD-IIIb, “MOH is headache occurring on 15 or more days per month developing as a consequence of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic headache medication (on 10 or more, or 15 or more days per month, depending on the medication) for more than 3 months. It usually, but not invariably, resolves after the overuse is stopped” (). With the present criteria, MOH can be diagnosed immediately, and independently of withdrawal.

Figure 1 International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd beta edition criteria for medication-overuse headache.

MOH is classified as a secondary chronic headache, but whether MOH is a primary or secondary headache is still under debate, and the concept of medication-overuse in other secondary headaches is unclear.Citation38,Citation39 Further, the concept of chronic migraine with medication-overuse is probably one of the most disputed aspects of the classification.Citation38

It is worthwhile noting that the classification does not depend on the number of drug units or dosage, but only count the number of days per month with medication use. Further, the pain characteristics and intensity are not a part of the diagnostic criteria since the location of pain varies in MOH.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of MOH in the general population in the western world is 1%–2%.Citation5,Citation6,Citation13,Citation40–Citation44 However, a recent review concludes that this varies in different parts of the world depending on the definitions used. The review reported a wide range of prevalence, ie, 0.5%–7.2%.Citation45 The incidence of MOH was 0.72 per 1,000 person-years in a large prospective cohort study from Norway.Citation46

The male to female ratio is 1:3–4, and the condition is most prevalent in the forties.Citation40,Citation44 The prevalence seems to decrease with increasing age, and among people over 65 years, the prevalence based on different definitions has been reported to be 1.0%–1.5%.Citation47,Citation48 The prevalence of MOH in children and adolescents has been suggested to be 0.3%–0.5%.Citation49,Citation50 In studies of specialist care in children, approximately 20% of patients with chronic headache had medication-overuse, suggesting MOH to be a problem also in school-aged children.Citation51,Citation52 It is suggested that MOH generally starts earlier in life than other types of chronic headache.Citation43

Medication use and health care utilization

While over-the-counter drugs are the most commonly overused headache medications in primary care, accounting for approximately 60% of overused medication, secondary and tertiary care have a greater proportion of MOH patients who overuse more potent centrally acting drugs like combination analgesics and opioids.Citation40,Citation41,Citation53–Citation57 In addition, many MOH patients overuse more than one type of acute medication.Citation27,Citation30

The drugs implicated in MOH change over time and differ between regions.Citation53 As an example, butalbital-containing medicine is still a problem in the USA, but is banned in the European Union.Citation58 Ergotamine is no longer the large problem it once was in western Europe, but still is in other parts of the world. However, triptans are now one of the most common causes of MOH in the Western world, but are probably too expensive to be a big problem in developing countries, where simple analgesics and ergotamine are much cheaper options.

The clinical features of MOH caused by different headache medications are quite similar. The fact that many patients overuse more than one type of acute headache drug makes it somewhat difficult to conclude if different types of drugs give different types of headache characteristics. However, one study showed that people overusing triptans developed a more migraine-like headache, in contrast with those overusing ergotamines and analgesics, who developed a more tension-type-like headache.Citation59 In another study, MOH caused by a combination of analgesics and triptans resulted in a higher frequency and intensity of headache, but this needs to be further explored.Citation60

In the general population, only 5%–15% of MOH patients use prophylactic medication, which is a low number considering the chronicity of the headache and frequent medication use.Citation54,Citation55,Citation61 The relative frequency of MOH in secondary and tertiary care is considerably higher than in primary care and in the general population. Headache clinics report that 50%–70% of their patients are overusing medication.Citation23,Citation57,Citation62–Citation65

Two studies have investigated health care utilization among MOH patients in the general population. In a Swedish study, 46% had made a headache-related visit to their general practitioner and 14% had visited a neurologist during the previous year.Citation61 The corresponding figures of lifetime headache-related contacts in a study from Norway were approximately 80% (general practitioner) and 20% (neurologist).Citation54,Citation55 Thus, most MOH patients have been in contact with their general practitioner, and many have had such contact in the previous year. More surprisingly, 20% self-managed their headache and had never consulted a physician.Citation54,Citation55 As many as three quarters of subjects in the Norwegian study had tried complementary and alternative treatment.Citation54,Citation55

Societal consequences of MOH

MOH patients experience reduced quality of life compared with those who do not suffer from headaches, but it is unknown if this is related to headache frequency or MOH per se, as chronic headache sufferers also show the same pattern.Citation43,Citation66,Citation67 Disability measured with the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire is high in MOH.Citation66,Citation68–Citation70 In the recent Global Burden of Disease Study,Citation4 MOH was not a part of the final analysis. However, based on the disability weight given MOH in the study and the high worldwide prevalence, it is speculated that MOH causes a highly significant number of years of life lost to disability.Citation71

In a recent assessment of direct and indirect costs of headache disorders in Europe, indirect loss due to reduced productivity and absenteeism accounted for about 90% of costs.Citation2 The individual costs of MOH were higher than those for migraine, and the total national costs for headache disorders in some countries were estimated to be higher for MOH than for migraine. Thus, MOH is probably the most costly headache disorder for both society and the sufferer, and the worldwide personal and economic costs are enormous.

Risk factors for MOH

It is well known that previous primary headaches such as migraine and tension-type headache are the most important risk factors for the development of MOH.Citation43,Citation64,Citation72 The proportion of patients with migraine or tension-type headache as their primary headache disorder differ depending on the classification used and at which health care level the investigation was conducted; 50%–70% have co-occurrence of migraine in population-based studies compared with 80%–100% for co-occurrence of migraine in studies from some headache centers.Citation5,Citation6,Citation26,Citation40,Citation65,Citation73

Many psychosocial and socioeconomic factors are associated with MOH. However, whether these are directly or indirectly associated is hard to ascertain because the findings are mainly based on cross-sectional studies. In addition, many of these factors may merely be markers of a complex health situation since many aspects may be affected by having chronic headache, as with other chronic conditions.

As for other frequent headaches, MOH patients tend to be of low socioeconomic status with low income and education, but it is uncertain whether this may be a cause of or an effect of headache.Citation40,Citation42,Citation61,Citation74,Citation75 A high prevalence of smoking, elevated body mass index, and sleeping problems have also been found among MOH patients.Citation42,Citation44 Depression and anxiety was more common in MOH patients than in people with episodic migraine, but in another study this was related to the headache frequency rather than headache diagnosis, so the cause-effect relationship is still unclear.Citation70,Citation76,Citation77 An association has also been shown for MOH and subclinical obsessive-compulsive disorders and mood disorders.Citation78

In one study, the risk of developing MOH was greater in individuals with a family history of MOH or other substance abuse, suggesting a possible hereditary susceptibility.Citation79 However, it is not possible based on that study to conclude whether this was due to genetic or environmental factors, or both.

Data from a population-based longitudinal study suggested that those who used analgesics daily or weekly at baseline compared with those without such medication use had a higher risk of developing chronic headache when followed up 11 years later.Citation14 A more recent study identified several risk factors for MOH among people with chronic headache (11 years follow-up).Citation46 Regular use of tranquilizers, a combination of chronic musculoskeletal disorders and gastrointestinal complaints, and increased Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score, as well as smoking and physical inactivity, increased the risk for MOH. The referred study is extensive and includes over 25,000 people at risk for chronic headache and MOH.Citation46 However, risk factors were only found in a minority of all MOH patients, and may reflect the complex situation for specific groups of MOH patients.Citation46

Pathogenesis

Approximately half of those who experience headache on ≥15 days per month have MOH.Citation5,Citation6 Most headache experts regard the association between overuse of acute medication and development of MOH as causal.Citation26,Citation80 Improvement in two thirds to three quarters of patients after successful medication withdrawal supports its causative role in generating or maintaining chronic headache. However, it is still a matter of debate whether the overuse is a consequence or cause of chronic headache.Citation81,Citation82 Further, not all headache patients with medication-overuse develop MOH, and the mechanism behind how chronic exposure to abortive medication leads to MOH remains unclear.

Virtually all acute headache medication may cause MOH. It has been suggested that the mean critical duration of overuse is shortest for triptans (1.7 years), longer for ergotamine (2.7 years), and longest for simple analgesics (4.8 years). The mean critical monthly intake frequency in the same study was lowest for triptans, higher for ergotamine, and highest for analgesics.Citation59

A pre-existing headache disorder seems to be required to develop MOH.Citation72 Patients with migraine or tension-type headache have a higher potential for developing MOH than other primary headaches.Citation43,Citation64 However, patients with cluster headaches may also develop MOH, but most of these patients have co-occurrence of migraine or a positive family history of migraine.Citation83 MOH does not develop in persons without a history of headache when medication is taken regularly for other conditions, such as arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease.Citation72,Citation84 Thus, a connection between headache-specific pain pathways and the effects of headache medication seems to be a central factor in generating a more chronic pain. However, since the different primary headaches have different underlying pathophysiology, and the different medications have different pharmacological actions, it is unlikely that MOH is caused by the specific action of any single agent. Mechanisms may differ from one class of overused drug to another, and different possible pathogenetic mechanisms have been suggested. It is of course possible that there is a common as yet unknown mechanism by which pharmacologically different medications lead to MOH independently of underlying primary headache. However, at present, it is possible only to describe mechanisms (mostly from preclinical studies) that appear to be associated with or may predispose people to develop MOH.

A hereditary susceptibility to MOH has been suggested, as the risk of developing MOH is greater in individuals with a family history of MOH or other substance abuse.Citation79 A few studies have identified molecular genetic factors that are possibly associated with both MOH and the response to treatment after withdrawal; however, these results are from small studies in selected groups and the generalizability of the findings is difficult to ascertain.Citation85–Citation88 Thus, further studies are required.

Alteration of cortical neuronal excitability, central sensitization involving the trigeminal nociceptive system, and changes in serotonergic and dopaminergic expression and pathways including the endocannabinoid system have been suggested to play a part in the pathophysiology of MOH.Citation85,Citation86,Citation89–Citation92

Low serotonin (5-HT) levels with reduction of 5-HT in platelets and up-regulation of a pro-nociceptive 5-HT2A receptor have been demonstrated in MOH.Citation93,Citation94 A higher frequency of CSD has been found in animals with low 5-HT levels, suggesting an association with sensitization processes.Citation95,Citation96 Further, chronic, but not acute, administration of paracetamol led to an increase in the frequency of cortical spreading depression in another rat model, which may indicate that chronic analgesic exposure leads to hyperexcitability in cortical neurons and an increase in cortical spreading depression.Citation97 A 5-HT2A receptor antagonist blocked this increased cortical spreading depression susceptibility in rats that had been exposed to chronic paracetamol.Citation98

Chronic use of opioids and triptans has been shown to increase calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels, which are involved in neurogenic inflammation and headache pain.Citation90,Citation99

In addition, chronic morphine infusion may alter diffuse noxious inhibitory controls, and impaired diffuse noxious inhibitory controls are also found in MOH.Citation100

Another important phenomenon related to MOH is central sensitization, which has for a long time been suggested to play an important role and has recently been described clinically in MOH patients with normalization after withdrawal of the overused medication.Citation101,Citation102

The endocannabinoid system is involved in modulating pain and plays a role in the common neurobiological system underlying drug addiction and reward.Citation103 Both an endocannabinoid membrane transporter and levels of endocannabinoids in platelets were reduced in MOH and chronic migraine patients compared with controls.Citation103,Citation104

In MOH patients, increased levels of orexin-A and corticotrophin-releasing hormone were found in the cerebrospinal fluid compared with levels in patients with chronic migraine, and were correlated with monthly drug intake.Citation105

In addition, neuroimaging studies suggest changes in the orbitofrontal cortex and the mesocorticolimbic dopamine circuit.Citation106–Citation109

In conclusion, the complex pathophysiology behind MOH is still only partly known. However, it is clear that many of these phenomena are similar to, and thus may involve, mechanisms seen in dependence processes,Citation89,Citation110 and it is equally clear that more research is needed in all these areas.

Medication dependence in MOH?

Whether MOH is a kind of dependence or just dependency-like behavior is still a matter of debate. Some authors have advocated the division of MOH into two subgroups depending on the type of overused medication and comorbidity.Citation111,Citation112

Codeine and opioids are not recommended in the treatment of tension-type headache or migraine. Regardless of this, it is well known that many MOH patients use these agents.Citation113,Citation114 Further, many countries have codeine (which is metabolized to opioids) and caffeine-containing analgesics available as over-the-counter drugs. Codeine, opioids, and caffeine are known to be psychotropic drugs, so abuse and dependence may be a problem with some headache drugs.Citation115–Citation117

Theoretical considerations also show many similarities between MOH and drug addiction.Citation110 In addition, recent studies in neuroimaging suggest an overlap of the pathophysiological mechanisms of MOH and substance-related disorders with changes in the orbitofrontal cortex and the mesocorticolimbic dopamine circuit.Citation106–Citation109

Although triptans and simple analgesics are not regarded as psychotropic agents, patients with MOH seem to share some characteristics with dependence. Previous studies from Norway have revealed that MOH can be easily detected in a population using a screening instrument for behavioral dependence, ie, the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS).Citation118–Citation120 The SDS has high sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for detecting chronic headache patients with MOH.Citation119–Citation121 In addition, the SDS score has been shown to predict the likelihood of successful detoxification in a general population.Citation122 However, the SDS has not been validated against other measurements of dependency in MOH sufferers.

In two studies, approximately 70% of MOH patients fulfilled criteria for dependence according to the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition).Citation123,Citation124 However, use of DSM-IV criteria in patients with MOH has been criticized since it may overestimate dependence.Citation125 In other studies, the dependence and personality profile score in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory II (MMPI-II) did not reveal any differences between MOH patients, drug addicts, and controls.Citation126,Citation127

Another study found that the dependency score based on the Leeds Dependency Questionnaire was similarly increased in MOH patients and illegal drug addicts.Citation128 However, in contrast with drug addicts, it was not the type of drug that was most important for the MOH patients, but the effect of the drug.Citation128 However, the high relapse into medication-overuse, even after successful withdrawal and improvement of the headache situation, has been suggested to be some kind of “drive” for medication.

A qualitative study suggested that patients with MOH hold on to what they consider to be “indispensable medication”.Citation129 The MOH patients were seeking for the pain relief; they did not view themselves as dependent and felt offended by that suggestion.Citation129

Based on today’s knowledge, it is impossible to ascertain whether the dependency-like behavior seen in those with MOH represents a real dependence or whether it is a form of “pseudoaddiction” secondary to frequent headache.Citation111,Citation112,Citation130–Citation132

Treatment

MOH is a treatable but very heterogeneous condition.Citation112,Citation130,Citation133 A further challenge in the treatment is the fact that no worldwide consensus for the management of these patients exists. This may be due to the lack of randomized controlled studies, but also reflects differences in use of headache classification and treatment strategies across the world.

Whether or not to detoxify MOH patients initially and whether prophylactic medication should be initiated immediately at withdrawal or after withdrawal therapy has been completed are probably the most disputed areas in the treatment of MOH.Citation26,Citation134–Citation136 Although recently debated, withdrawal of the overused medication(s) is regarded by most headache experts as the treatment of choice, since withdrawal of the overused medication(s) in most cases leads to an improvement of the headache.Citation26,Citation57,Citation134,Citation135,Citation137

Most patients experience withdrawal symptoms lasting 2–10 days after detoxification. The most common symptom is an initial worsening of the headache (rebound-headache), accompanied by various degrees of nausea, vomiting, hypotension, tachycardia, sleep disturbances, restlessness, anxiety, and nervousness. The duration of withdrawal headaches has been found to vary with different drugs, being shorter in patients overusing triptans than in those overusing ergotamine or analgesics.Citation138

Detoxification procedures vary widely and include both inpatient (2 days to 2 weeks) and outpatient withdrawal.Citation73,Citation133,Citation139–Citation142 The different strategies include abrupt or tapered withdrawal with just simple advice, multidisciplinary approaches, use of antiemetics, neuroleptics, rescue medication (an analgesic other than the overused one), and intravenous hydration. Steroids have for a long time been expected to alleviate withdrawal headache in the acute phase, but two placebo-controlled studies did not find prednisolone (60 mg or 100 mg for 5 days) superior to placebo.Citation143,Citation144 However, it is still debated if it may be useful in certain subgroups of patients.

Independent of the strategy used, the main aims of treatment are withdrawal of the overused medication and continuing support (pharmacological and nonpharmacological) to prevent relapse. Comorbidity with other medical conditions (including psychiatric disorders) has to be treated in addition to withdrawal therapy to avoid relapse.

Headache centers often report treatment success rates of around 70%. These results are commonly based on inpatient treatment, rescue medication, and continued support. However, the definition of success rate is based on very variable outcome measures and therefore difficult to compare.Citation145

Some studies have supported the effect of simple advice for MOH in the general population and in a headache clinic.Citation133,Citation146–Citation148 In a previous population-based study from Norway, simple information on medication use led to improvement, with 42% of patients reverting to episodic headache and 76% being free of medication-overuse after 1.5 years. The study was observational and lacked a control group, but the effect of simple information was supported by the fact that the participants had had MOH for 8–18 years prior to the interview during which the information was given.Citation146 Two Italian studies in neurology settings reported that 78%–92% of patients with simple MOH and 60% of those with complicated MOH became free of chronic headache and medication-overuse 2 months after receiving simple advice.Citation133,Citation147,Citation148 Even previously treatment-resistant MOH patients from a tertiary headache center experienced lasting improvement after withdrawal of medication.Citation69 Based on our clinical experience, most patients overusing simple analgesics as well as codeine-containing combination analgesics and triptans manage abrupt withdrawal without tapering. Patients overusing heavier drugs with physical abstinence profiles may be a different matter and these patients may need other withdrawal strategies.

However, in most countries in Europe, simple analgesics, triptans, and combination analgesics clearly dominate.Citation40,Citation43,Citation54,Citation55 Because there seems to be no difference between inpatient and outpatient withdrawal, the less resource-demanding outpatient withdrawal is in our opinion the preferred method.Citation133,Citation139,Citation141,Citation149

Placebo-controlled studies of various prophylactic medications (adding prophylactic medication without initial withdrawal) in the treatment of MOH have found a significant reduction in migraine and headache days per month compared with placebo.Citation136,Citation150–Citation154 However, there are methodological concerns with these studies when addressing MOH, in particular based on the inclusion of a mixed population of chronic migraine with and without medication-overuse. However, these results do not seem to be superior to initial detoxification without prophylactic medication in other studies.Citation73,Citation133,Citation135 Recent studies from headache centers have also used the combination of initial withdrawal and prophylactic medication with some superiority when compared with only initial withdrawal in the short-term; however, in the long-term results, there are no differences between the groups with or without prophylactic medication.Citation69,Citation73,Citation155

Therefore, based on today’s knowledge, we suggest that initial withdrawal is the treatment of choice. Prophylactic headache medication should be restricted to patients who do not benefit sufficiently from cessation of medication-overuse, and those who have previously failed withdrawal attempts or have significant comorbidity. Some authors contest this view since many MOH patients are already suffering and heavily disabled before starting a possible troublesome detoxification with withdrawal symptoms. However, it is an aim in itself to achieve a behavioral change and to restructure the approach from “have pain – take tablet” thinking to better ways of handling headache. In addition, a period free of medication-overuse has been suggested to lead to recovery of prophylactic responsiveness.Citation156 For patients still needing prophylactic medication after withdrawal, the choice should be based on the underlying primary headache, comorbidity, and possible side effects of treatment. Other more experimental treatments, such as surgery and neuromodulation, have conflicting results and should not be recommended before new evidence clearly demonstrates a clinical effect.Citation157,Citation158

Long-term outcome and relapse rate

Most follow-up studies are conducted in tertiary care centers and may reflect selected populations. However, one study supports that patients initially detoxified as inpatients can be followed up by their general practitioner.Citation159

Studies have reported a 20%–40% relapse rate within the first year after withdrawal. Only few relapse after 12 months.Citation159–Citation166 There are conflicting results regarding at what time during the first year patients relapse, with some suggesting that most patients relapse within the first 6 months and others suggesting between 6 and 12 months.Citation160–Citation162,Citation166,Citation167 The literature is not clear regarding to what degree the pre-existent headache type or type of overused medication predicts successful withdrawal or relapse.Citation59,Citation159–Citation166 In addition, the results on relapse should be compared with some caution, since the studies varied in their use of headache classification systems, withdrawal, and prophylaxis, as well as in duration of follow-up and the criteria used to detect improvement.

Prevention

A small study from England reported that both people with headache and those without headache were unaware of the risk of MOH resulting from frequent analgesic use for headache.Citation168 Other studies have found that most MOH patients do not know about the relationship between medication-overuse and headache chronification.Citation61,Citation62,Citation147 The authors suggest it is possible that the patients had been informed but did not remember or had not fully understood the information. In a German study, a brochure on medication-overuse helped to prevent development of MOH in people with migraine and frequent medication use.Citation169

Considering that possibly anyone with primary episodic headache may be at risk of developing MOH, the number of people at risk is high. Adding the fact that, in many cases, just simple advice leads to successful medication withdrawal, the potential benefit of giving information on MOH is high. New information campaigns and strategies to target people at risk have to be developed.

Given that most patients with MOH have been in contact with a general practitioner, and almost half have had such contact in the previous year, primary care is probably the ideal setting for prevention and treatment of headache and medication-overuse.Citation54,Citation55,Citation61 The general practitioner has a key role in providing patient education and prophylactic headache medication before headaches become chronic. Further, general practitioners have the continued and clear responsibility for the patients over time. This long-term alliance with their own patients may further enhance the treatment effects and avoidance of relapse. Taking care of uncomplicated cases in primary care may also free up more resources for referrals to neurologists of complicated cases.

Conclusion

MOH is a treatable and preventable public health problem worldwide. The improvements seen in two of three MOH patients after withdrawal suggest that detoxification is the logical first step in treatment. Prevention as well as treatment should probably be attempted in primary care, leaving the more complicated cases to neurologists. The gain from treating patients with MOH is potentially high, and may lead to substantial economic savings for society as well as for individual patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors received research funding for this work from the Research Centre at Akershus University Hospital, and the University of Oslo.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- JensenRStovnerLJEpidemiology and comorbidity of headacheLancet Neurol20087435436118339350

- LindeMGustavssonAStovnerLJThe cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight projectEur J Neurol201219570371122136117

- StovnerLHagenKJensenRThe global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwideCephalalgia200727319321017381554

- VosTFlaxmanADNaghaviMYears lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592163219623245607

- AasethKGrandeRBKvaernerKJGulbrandsenPLundqvistCRussellMBPrevalence of secondary chronic headaches in a population-based sample of 30–44-year-old persons. The Akershus study of chronic headacheCephalalgia200828770571318498398

- GrandeRBAasethKGulbrandsenPLundqvistCRussellMBPrevalence of primary chronic headache in a population-based sample of 30- to 44-year-old persons. The Akershus study of chronic headacheNeuroepidemiology2008302768318277081

- Lantéri-MinetMAurayJPEl HasnaouiAPrevalence and description of chronic daily headache in the general population in FrancePain20031021–214314912620605

- CastilloJMunozPGuiteraVPascualJKaplan Award 1998. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general populationHeadache199839319019615613213

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache SocietyThe International Classification of Headache Disorders. 3rd ed (beta version)Cephalalgia201333962980823771276

- LatinovicRGullifordMRidsdaleLHeadache and migraine in primary care: consultation, prescription, and referral rates in a large populationJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200677338538716484650

- RidsdaleLClarkLVDowsonAJHow do patients referred to neurologists for headache differ from those managed in primary care?Br J Gen Pract20075753838839517504590

- PattersonVHEsmondeTFComparison of the handling of neurological outpatient referrals by general physicians and a neurologistJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19935678308331364

- ZwartJADybGHagenKSvebakSStovnerLJHolmenJAnalgesic overuse among subjects with headache, neck, and low-back painNeurology20046291540154415136678

- ZwartJADybGHagenKAnalgesic use: a predictor of chronic pain and medication overuse headacheNeurology200361216016412874392

- EggenAEThe Tromso Study: frequency and predicting factors of analgesic drug use in a free-living population (12–56 years)J Clin Epidemiol19934611129713048229107

- AntonovKIIsacsonDGPrescription and nonprescription analgesic use in SwedenAnn Pharmacother19983244854949562147

- MehuysEPaemeleireKVan HeesTSelf-medication of regular headache: a community pharmacy-based surveyEur J Neurol20121981093109922360745

- PorteousTBondCHannafordPSinclairHHow and why are non-prescription analgesics used in Scotland?Fam Pract2005221788515640291

- HargreaveMAndersenTVNielsenAMunkCLiawKLKjaerSKFactors associated with continuous regular analgesic use – a population-based study of more than 45,000 Danish women and men 18–45 years of agePharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2010191657419757417

- HortonBTPetersGAClinical manifestations of excessive use of ergotamine preparations and mangement of withdrawal effect: report of 52 casesHeadache1963221422713964041

- PetersGAHortonBTHeadache: with special reference to the excessive use of ergotamine preparations and withdrawal effectsProc Staff Meet Mayo Clin195126915316114827944

- PetersGAHortonBTHeadache; with special reference to the excessive use of ergotamine tartrate and dihydroergotamineJ Lab Clin Med195036697297314795057

- MathewNTKurmanRPerezFDrug induced refractory headache-clinical features and managementHeadache199030106346382272811

- DienerHCDichgansJScholzEGeiselhartSGerberWDBilleAAnalgesic-induced chronic headache: long-term results of withdrawal therapyJ Neurol198923619142915233

- KudrowLParadoxical effects of frequent analgesic useAdv Neurol1982333353417055014

- EversSJensenREuropean Federation of Neurological SocietiesTreatment of medication overuse headache – guideline of the EFNS headache panelEur J Neurol20111891115112121834901

- DienerHCLimmrothVMedication-overuse headache: a worldwide problemLancet Neurol20043847548315261608

- KatsaravaZJensenRMedication-overuse headache: where are we now?Curr Opin Neurol200720332633017495628

- RossiPJensenRNappiGAllenaMCOMOESTAS ConsortiumA narrative review on the management of medication overuse headache: the steep road from experience to evidenceJ Headache Pain200910640741719802522

- EversSMarziniakMClinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment of medication-overuse headacheLancet Neurol20109439140120298963

- KristoffersenESLundqvistCMedication-overuse headache: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatmentTher Adv Drug Saf2014528799

- Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache of the National Institute of HealthClassification of headacheJAMA1962179717718

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache SocietyClassification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial painCephalalgia19888Suppl 7196

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache SocietyThe International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edCephalalgia200424Suppl 1916014979299

- CephalalgiaErratumCephalalgia2006263360

- OlesenJBousserMGDienerHCNew appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraineCephalalgia200626674274616686915

- SilbersteinSDOlesenJBousserMGThe International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed (ICHD-II) – revision of criteria for 8.2 Medication-overuse headacheCephalalgia200525646046515910572

- Sun-EdelsteinCBigalMERapoportAMChronic migraine and medication overuse headache: clarifying the current International Headache Society classification criteriaCephalalgia200929444545219291245

- GrazziLBussoneGMedication overuse headache (MOH): complication of migraine or secondary headache?Neurol Sci201233Suppl 1S27S2822644165

- JonssonPHedenrudTLindeMEpidemiology of medication overuse headache in the general Swedish populationCephalalgia20113191015102221628444

- LuSRFuhJLChenWTJuangKDWangSJChronic daily headache in Taipei, Taiwan: prevalence, follow-up and outcome predictorsCephalalgia2001211098098611843870

- WiendelsNJKnuistingh NevenARosendaalFRChronic frequent headache in the general population: prevalence and associated factorsCephalalgia200626121434144217116093

- ColásRMuñozPTempranoRGómezCPascualJChronic daily headache with analgesic overuse: epidemiology and impact on quality of lifeNeurology20046281338134215111671

- StraubeAPfaffenrathVLadwigKHPrevalence of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache in Germany – the German DMKG Headache StudyCephalalgia201030220721319489879

- WestergaardMLHansenEHGlumerCOlesenJJensenRHDefinitions of medication-overuse headache in population-based studies and their implications on prevalence estimates: a systematic reviewCephalalgia201434640942524293089

- HagenKLindeMSteinerTJStovnerLJZwartJARisk factors for medication-overuse headache: an 11-year follow-up study. The Nord-Trøndelag Health StudiesPain20121531566122018971

- WangSJFuhJLLuSRChronic daily headache in Chinese elderly: prevalence, risk factors, and biannual follow-upNeurology200054231431910668689

- PrencipeMCasiniARFerrettiCPrevalence of headache in an elderly population: attack frequency, disability, and use of medicationJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200170337738111181862

- WangSJFuhJLLuSRJuangKDChronic daily headache in adolescents: prevalence, impact, and medication overuseNeurology200666219319716434652

- DybGHolmenTLZwartJAAnalgesic overuse among adolescents with headache: the Head-HUNT-Youth StudyNeurology200666219821016434653

- PiazzaFChiappediMMaffiolettiEGalliFBalottinUMedication overuse headache in school-aged children: more common than expected?Headache201252101506151022822711

- WiendelsNJvan der GeestMCNevenAKFerrariMDLaanLAChronic daily headache in children and adolescentsHeadache200545667868315953300

- MeskunasCATepperSJRapoportAMSheftellFDBigalMEMedications associated with probable medication overuse headache reported in a tertiary care headache center over a 15-year periodHeadache200646576677216643579

- KristoffersenESGrandeRBAasethKLundqvistCRussellMBManagement of primary chronic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headacheJ Headache Pain201213211312021993986

- KristoffersenESLundqvistCAasethKGrandeRBRussellMBManagement of secondary chronic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headacheJ Headache Pain2013141523565808

- ScherAILiptonRBStewartWFBigalMPatterns of medication use by chronic and episodic headache sufferers in the general population: results from the frequent headache epidemiology studyCephalalgia201030332132819614708

- ZeebergPOlesenJJensenRProbable medication-overuse headache: the effect of a 2-month drug-free periodNeurology200666121894189816707727

- Tfelt-HansenPCDienerHCWhy should American headache and migraine patients still be treated with butalbital-containing medicine?Headache201252467267422404123

- LimmrothVKatsaravaZFritscheGPrzywaraSDienerHCFeatures of medication overuse headache following overuse of different acute headache drugsNeurology20025971011101412370454

- Creac’hCRadatFMickGOne or several types of triptan overuse headaches?Headache200949451952819245390

- JonssonPLindeMHensingGHedenrudTSociodemographic differences in medication use, health-care contacts and sickness absence among individuals with medication-overuse headacheJ Headache Pain201213428129022427000

- BekkelundSISalvesenRDrug-associated headache is unrecognized in patients treated at a neurological centreActa Neurol Scand2002105212012311903122

- DowsonAJAnalysis of the patients attending a specialist UK headache clinic over a 3-year periodHeadache2003431141812864753

- BigalMELiptonRBExcessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progressionNeurology200871221821182819029522

- BigalMERapoportAMSheftellFDTepperSJLiptonRBTransformed migraine and medication overuse in a tertiary headache centre – clinical characteristics and treatment outcomesCephalalgia200424648349015154858

- Lanteri-MinetMDuruGMudgeMCottrellSQuality of life impairment, disability and economic burden associated with chronic daily headache, focusing on chronic migraine with or without medication overuse: a systematic reviewCephalalgia201131783785021464078

- WiendelsNJvan HaestregtAKnuistingh NevenAChronic frequent headache in the general population: comorbidity and quality of lifeCephalalgia200626121443145017116094

- BendtsenLMunksgaardSTassorelliCDisability, anxiety and depression associated with medication-overuse headache can be considerably reduced by detoxification and prophylactic treatment. Results from a multicentre, multinational study (COMOESTAS project)Cephalalgia201434642643324322480

- MunksgaardSBBendtsenLJensenRHTreatment-resistant medication overuse headache can be curedHeadache20125271120112922724425

- WallaschTMKroppPMultidisciplinary integrated headache care: a prospective 12-month follow-up observational studyJ Headache Pain201213752152922790281

- SteinerTCan we know the prevalence of MOH?Cephalalgia201434640340424500815

- BahraAWalshMMenonSGoadsbyPJDoes chronic daily headache arise de novo in association with regular use of analgesics?Headache200343317919012603636

- MunksgaardSBBendtsenLJensenRHDetoxification of medication-overuse headache by a multidisciplinary treatment programme is highly effective: a comparison of two consecutive treatment methods in an open-label designCephalalgia2012321183484422751965

- HagenKVattenLStovnerLJZwartJAKrokstadSBovimGLow socio-economic status is associated with increased risk of frequent headache: a prospective study of 22718 adults in NorwayCephalalgia200222867267912383064

- AtasoyHTUnalAEAtasoyNEmreUSumerMLow income and education levels may cause medication overuse and chronicity in migraine patientsHeadache2005451253115663609

- RadatFCreac’hCSwendsenJDPsychiatric comorbidity in the evolution from migraine to medication overuse headacheCephalalgia200525751952215955038

- ZwartJADybGHagenKDepression and anxiety disorders associated with headache frequency. The Nord-Trondelag Health StudyEur J Neurol200310214715212603289

- CupiniLMDeMMCostaCObsessive-compulsive disorder and migraine with medication-overuse headacheHeadache20094971005101319496831

- CevoliSSancisiEGrimaldiDFamily history for chronic headache and drug overuse as a risk factor for headache chronificationHeadache200949341241819267785

- BigalMELiptonRBOveruse of acute migraine medications and migraine chronificationCurr Pain Headache Rep200913430130719586594

- DodickDWDebate: analgesic overuse is a cause, not consequence, of chronic daily headache. Analgesic overuse is not a cause of chronic daily headacheHeadache200242654755412167149

- TepperSJDebate: analgesic overuse is a cause, not consequence, of chronic daily headache. Analgesic overuse is a cause of chronic daily headacheHeadache200242654354712167148

- PaemeleireKBahraAEversSMatharuMSGoadsbyPJMedication-overuse headache in patients with cluster headacheNeurology200667110911316832088

- WilkinsonSMBeckerWJHeineJAOpiate use to control bowel motility may induce chronic daily headache in patients with migraineHeadache200141330330911264692

- CevoliSMochiMScapoliCA genetic association study of dopamine metabolism-related genes and chronic headache with drug abuseEur J Neurol20061391009101316930369

- Di LorenzoCDi LorenzoGSancesGDrug consumption in medication overuse headache is influenced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphismJ Headache Pain200910534935519517061

- Di LorenzoCSancesGDi LorenzoGThe wolframin His611Arg polymorphism influences medication overuse headacheNeurosci Lett2007424317918417719176

- CargninSVianaMGhiottoNFunctional polymorphisms in COMT and SLC6A4 genes influence the prognosis of patients with medication overuse headache after withdrawal therapyEur J Neurol Epub2014329

- CupiniLMSarchielliPCalabresiPMedication overuse headache: neurobiological, behavioural and therapeutic aspectsPain2010150222222420546999

- De FeliceMOssipovMHWangRTriptan-induced latent sensitization: a possible basis for medication overuse headacheAnn Neurol201067332533720373344

- MengIDDodickDOssipovMHPorrecaFPathophysiology of medication overuse headache: insights and hypotheses from preclinical studiesCephalalgia201131785186021444643

- Bongsebandhu-phubhakdiSSrikiatkhachornAPathophysiology of medication-overuse headache: implications from animal studiesCurr Pain Headache Rep201216111011522076674

- SrikiatkhachornAAnthonyMSerotonin receptor adaptation in patients with analgesic-induced headacheCephalalgia20061664194228902250

- SrikiatkhachornAManeesriSGovitrapongPKasantikulVDerangement of serotonin system in migrainous patients with analgesic abuse headache: clues from plateletsHeadache199838143499505003

- SupornsilpchaiWSanguanrangsirikulSManeesriSSrikiatkhachornASerotonin depletion, cortical spreading depression, and trigeminal nociceptionHeadache2006461343916412149

- le GrandSMSupornsilpchaiWSaengjaroenthamCSrikiatkhachornASerotonin depletion leads to cortical hyperexcitability and trigeminal nociceptive facilitation via the nitric oxide pathwayHeadache20115171152116021649655

- SupornsilpchaiWle GrandSMSrikiatkhachornACortical hyperexcitability and mechanism of medication-overuse headacheCephalalgia20103091101110920713560

- SupornsilpchaiWle GrandSMSrikiatkhachornAInvolvement of pro-nociceptive 5-HT2A receptor in the pathogenesis of medication-overuse headacheHeadache201050218519720039957

- BelangerSMaWChabotJGQuirionRExpression of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P and protein kinase C in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons following chronic exposure to mu, delta and kappa opiatesNeuroscience2002115244145312421610

- PerrottaASerraoMSandriniGSensitisation of spinal cord pain processing in medication overuse headache involves supraspinal pain controlCephalalgia201030327228419614707

- AyzenbergIObermannMNyhuisPCentral sensitization of the trigeminal and somatic nociceptive systems in medication overuse headache mainly involves cerebral supraspinal structuresCephalalgia20062691106111416919061

- MunksgaardSBBendtsenLJensenRHModulation of central sensitisation by detoxification in MOH: Results of a 12-month detoxification studyCephalalgia201333744445323431023

- CupiniLMCostaCSarchielliPDegradation of endocannabinoids in chronic migraine and medication overuse headacheNeurobiol Dis200830218618918358734

- RossiCPiniLACupiniMLCalabresiPSarchielliPEndocannabinoids in platelets of chronic migraine patients and medication-overuse headache patients: relation with serotonin levelsEur J Clin Pharmacol20086411818004553

- SarchielliPRaineroICoppolaFInvolvement of corticotrophin-releasing factor and orexin-A in chronic migraine and medication-overuse headache: findings from cerebrospinal fluidCephalalgia200828771472218479471

- ChanraudSDi ScalaGDilharreguyBSchoenenJAllardMRadatFBrain functional connectivity and morphology changes in medication-overuse headache: Clue for dependence-related processes?Cephalalgia Epub2014121

- FerraroSGrazziLMuffattiRIn medication-overuse headache, fMRI shows long-lasting dysfunction in midbrain areasHeadache201252101520153423094707

- GrazziLChiappariniLFerraroSChronic migraine with medication overuse pre-post withdrawal of symptomatic medication: clinical results and fMRI correlationsHeadache2010506998100420618816

- FumalALaureysSDi ClementeLOrbitofrontal cortex involvement in chronic analgesic-overuse headache evolving from episodic migraineBrain2006129Pt 254355016330505

- CalabresiPCupiniLMMedication-overuse headache: similarities with drug addictionTrends Pharmacol Sci2005262626815681022

- SaperJRLakeAE3rdMedication overuse headache: type I and type IICephalalgia20062610126216961800

- LakeAE3rdMedication overuse headache: biobehavioral issues and solutionsHeadache200646Suppl 3S88S9717034403

- BendtsenLEversSLindeMEFNS guideline on the treatment of tension-type headache – report of an EFNS task forceEur J Neurol201017111318132520482606

- EversSAfraJFreseAEFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine – revised report of an EFNS task forceEur J Neurol200916996898119708964

- AbbottFVFraserMIUse and abuse of over-the-counter analgesic agentsJ Psychiatry Neurosci199823113349505057

- CooperRJOver-the-counter medicine abuse – a review of the literatureJ Subst Use20131828210723525509

- CooperRJ‘I can’t be an addict. I am.’ Over-the-counter medicine abuse: a qualitative studyBMJ Open201336

- GossopMDarkeSGriffithsPThe Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine usersAddiction19959056076147795497

- GrandeRBAasethKSaltyte BenthJGulbrandsenPRussellMBLundqvistCThe Severity of Dependence Scale detects people with medication overuse: the Akershus study of chronic headacheJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200980778478919279030

- LundqvistCAasethKGrandeRBBenthJSRussellMBThe severity of dependence score correlates with medication overuse in persons with secondary chronic headaches. The Akershus study of chronic headachePain2010148348749120071079

- LundqvistCBenthJSGrandeRBAasethKRussellMBAn adapted Severity of Dependence Scale is valid for the detection of medication overuse: the Akershus study of chronic headacheEur J Neurol201118351251820825471

- LundqvistCGrandeRBAasethKRussellMBDependence scores predict prognosis of medication overuse headache: a prospective cohort from the Akershus study of chronic headachePain2012153368268622281099

- FuhJLWangSJLuSRJuangKDDoes medication overuse headache represent a behavior of dependence?Pain20051191–3495516298069

- RadatFCreac’hCGuegan-MassardierEBehavioral dependence in patients with medication overuse headache: a cross-sectional study in consulting patients using the DSM-IV criteriaHeadache20084871026103618081820

- LauwerierEPaemeleireKVan DammeSGoubertLCrombezGMedication use in patients with migraine and medication-overuse headache: the role of problem-solving and attitudes about pain medicationPain201115261334133921396772

- GalliFPozziGFrustaciADifferences in the personality profile of medication-overuse headache sufferers and drug addict patients: a comparative study using MMPI-2Headache20115181212122721884080

- SancesGGalliFAnastasiSMedication-overuse headache and personality: a controlled study by means of the MMPI-2Headache201050219820920039955

- FerrariACiceroAFBertoliniALeoneSPasciulloGSternieriENeed for analgesics/drugs of abuse: a comparison between headache patients and addicts by the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ)Cephalalgia200626218719316426274

- JonssonPJakobssonAHensingGLindeMMooreCDHedenrudTHolding on to the indispensable medication – a grounded theory on medication use from the perspective of persons with medication overuse headacheJ Headache Pain20131414323697986

- SaperJRHamelRLLakeIII AEMedication overuse headache (MOH) is a biobehavioural disorderCephalalgia200525754554615955043

- FuhJLWangSJDependent behavior in patients with medication-overuse headacheCurr Pain Headache Rep2012161737922125111

- RadatFLanteri-MinetMWhat is the role of dependence-related behavior in medication-overuse headache?Headache201050101597161120807250

- RossiPFaroniJVNappiGShort-term effectiveness of simple advice as a withdrawal strategy in simple and complicated medication overuse headacheEur J Neurol201118339640120629723

- DienerHCDetoxification for medication overuse headache is not necessaryCephalalgia201232542342722127226

- OlesenJDetoxification for medication overuse headache is the primary taskCephalalgia201232542042222174362

- HagenKAlbretsenCVilmingSTManagement of medication overuse headache: 1-year randomized multicentre open-label trialCephalalgia200929222123218823363

- Linton-DahlöfPLindeMDahlöfCWithdrawal therapy improves chronic daily headache associated with long-term misuse of headache medication: a retrospective studyCephalalgia200020765866211128824

- KatsaravaZFritscheGMuessigMDienerHCLimmrothVClinical features of withdrawal headache following overuse of triptans and other headache drugsNeurology20015791694169811706113

- KrymchantowskiAVMoreiraPFOut-patient detoxification in chronic migraine: comparison of strategiesCephalalgia2003231098299314984232

- GrazziLAndrasikFUsaiSBussoneGIn-patient vs day-hospital withdrawal treatment for chronic migraine with medication overuse and disability assessment: results at one-year follow-upNeurol Sci200829Suppl 1S161S16318545923

- Creac’hCFrappePCancadeMIn-patient versus out-patient withdrawal programmes for medication overuse headache: a 2-year randomized trialCephalalgia201131111189119821700646

- GaulCBromstrupJFritscheGDienerHCKatsaravaZEvaluating integrated headache care: a one-year follow-up observational study in patients treated at the Essen headache centreBMC Neurol20111112421985562

- BoeMGMyglandASalvesenRPrednisolone does not reduce withdrawal headache: a randomized, double-blind studyNeurology2007691263117475943

- RabeKPagelerLGaulCPrednisone for the treatment of withdrawal headache in patients with medication overuse headache: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyCephalalgia201333320220723093541

- HagenKJensenRBoeMGStovnerLJMedication overuse headache: a critical review of end points in recent follow-up studiesJ Headache Pain201011537337720473701

- GrandeRBAasethKBenthJSLundqvistCRussellMBReduction in medication-overuse headache after short information. The Akershus study of chronic headacheEur J Neurol201118112913720528911

- RossiPDiLCFaroniJCesarinoFNappiGDi LorenzoCAdvice alone vs structured detoxification programmes for medication overuse headache: a prospective, randomized, open-label trial in transformed migraine patients with low medical needsCephalalgia20062691097110516919060

- RossiPFaroniJVTassorelliCNappiGAdvice alone versus structured detoxification programmes for complicated medication overuse headache (MOH): a prospective, randomized, open-label trialJ Headache Pain20131411023565591

- TassorelliCJensenRAllenaMA consensus protocol for the management of medication-overuse headache: evaluation in a multicentric, multinational studyCephalalgia Epub2014220

- DienerHCDodickDWGoadsbyPJUtility of topiramate for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine in the presence or absence of acute medication overuseCephalalgia200929101021102719735529

- DienerHCDodickDWAuroraSKOnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trialCephalalgia201030780481420647171

- AuroraSKDodickDWTurkelCCOnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trialCephalalgia201030779380320647170

- SandriniGPerrottaATassorelliCBotulinum toxin type-A in the prophylactic treatment of medication-overuse headache: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group studyJ Headache Pain201112442743321499747

- SilbersteinSDBlumenfeldAMCadyRKOnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: PREEMPT 24-week pooled subgroup analysis of patients who had acute headache medication overuse at baselineJ Neurol Sci20133311–2485623790235

- SarchielliPMessinaPCupiniLMSodium valproate in migraine without aura and medication overuse headache: a randomized controlled trialEur Neuropsychopharmacol Epub201445

- ZeebergPOlesenJJensenRDiscontinuation of medication overuse in headache patients: recovery of therapeutic responsivenessCephalalgia200626101192119816961785

- MartellettiPJensenRHAntalANeuromodulation of chronic headaches: position statement from the European Headache FederationJ Headache Pain20131418624144382

- FreemanJATrentmanTLClinical utility of implantable neurostimulation devices in the treatment of chronic migraineMed Devices (Auckl)2013619520124348076

- BoeMGSalvesenRMyglandAChronic daily headache with medication overuse: a randomized follow-up by neurologist or PCPCephalalgia200929885586319228151

- GrazziLAndrasikFD’AmicoDUsaiSKassSBussoneGDisability in chronic migraine patients with medication overuse: treatment effects at 1-year follow-upHeadache200444767868315209690

- KatsaravaZLimmrothVFinkeMDienerHCFritscheGRates and predictors for relapse in medication overuse headache: a 1-year prospective studyNeurology200360101682168312771266

- KatsaravaZMuessigMDzagnidzeAFritscheGDienerHCLimmrothVMedication overuse headache: rates and predictors for relapse in a 4-year prospective studyCephalalgia2005251121515606564

- Zidverc-TrajkovicJPekmezovicTJovanovicZMedication overuse headache: clinical features predicting treatment outcome at 1-year follow-upCephalalgia200727111219122517888081

- BoeMGSalvesenRMyglandAChronic daily headache with medication overuse: predictors of outcome 1 year after withdrawal therapyEur J Neurol200916670571219236455

- RossiPFaroniJVNappiGMedication overuse headache: predictors and rates of relapse in migraine patients with low medical needs. A 1-year prospective studyCephalalgia200828111196120018727648

- AndrasikFGrazziLUsaiSKassSBussoneGDisability in chronic migraine with medication overuse: treatment effects through 5 yearsCephalalgia201030561061419614686

- GhiottoNSancesGGalliFMedication overuse headache and applicability of the ICHD-II diagnostic criteria: 1-year follow-up study (CARE I protocol)Cephalalgia200929223324319025549

- LaiJTDereixJDGanepolaRPShould we educate about the risks of medication overuse headache?J Headache Pain2014151024524380

- FritscheGFrettlohJHuppeMPrevention of medication overuse in patients with migrainePain2010151240441320800968