Abstract

Background. To investigate post-treatment changes in serum testosterone in low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients treated with hypofractionated passively scattered proton radiotherapy. Material and methods. Between April 2008 and October 2011, 228 patients with low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer were enrolled into an institutional review board-approved prospective protocol. Patients received doses ranging from 70 Cobalt Gray Equivalent (CGE) to 72.5 CGE at 2.5 CGE per fraction using passively scattered protons. Three patients were excluded for receiving androgen deprivation therapy (n = 2) or testosterone supplementation (n = 1) before radiation. Of the remaining 226 patients, pretreatment serum testosterone levels were available for 217. Of these patients, post-treatment serum testosterone levels were available for 207 in the final week of treatment, 165 at the six-month follow-up, and 116 at the 12-month follow-up. The post-treatment testosterone levels were compared with the pretreatment levels using Wilcoxon's signed-rank test for matched pairs. Results. The median pretreatment serum testosterone level was 367.7 ng/dl (12.8 nmol/l). The median changes in post-treatment testosterone value were as follows: +3.0 ng/dl (+0.1 nmol/l) at treatment completion; +6.0 ng/dl (+0.2 nmol/l) at six months after treatment; and +5.0 ng/dl (0.2 nmol/l) at 12 months after treatment. None of these changes were statistically significant. Conclusion. Patients with low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with hypofractionated passively scattered proton radiotherapy do not experience testosterone suppression. Our findings are consistent with physical measurements demonstrating that proton radiotherapy is associated with less scatter radiation exposure to tissues beyond the beam paths compared with intensity-modulated photon radiotherapy.

Prostate cancer has been found to have a low α/β ratio, suggesting that high dose-per-fraction radiotherapy (RT) may have a relatively greater killing effect on cancer cells compared to conventionally fractionated RT [Citation1–3]. Several studies evaluating hypofractionated intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) for patients with localized prostate cancer have demonstrated acceptable toxicity profiles with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) control rates comparable to those achieved with conventionally fractionated treatment [Citation4,Citation5].

Photon-based external-beam RT for prostate cancer, in a number of studies, has been associated with a decline in the patient's serum testosterone level after treatment [Citation6–10]. This decline in serum testosterone may be a result of scatter radiation to the testes or a non-specific stress response. If, in fact, the decline in serum testosterone is due to scatter radiation, this effect may be more pronounced for patients treated with escalated doses, larger radiation fields, or multiple-field plans, as occurs during IMRT with the delivery of many monitor units.

Proton therapy is a highly conformal type of RT. In contrast to advanced x-ray-based therapies such as IMRT which achieve conformality by delivering multiple beams from multiple angles intersecting on the target, proton therapy achieves conformality by modulating the intensity of the dose deposition along the beam path. Data support proton therapy as an effective treatment with minimal side effects for men with prostate cancer [Citation11,Citation12]. Additionally, based on physical measurement, proton therapy is associated with less scatter radiation to tissues beyond the beam paths than photon IMRT when the prostate is irradiated [Citation13].

Previously, our institution reported that conventionally fractionated proton therapy for prostate cancer was not associated with a decline in serum testosterone levels after treatment for a group of 171 patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease treated on two prospective institutional review board (IRB)-approved studies [Citation14]. We had no a prior reason to believe that hypofractionated proton therapy would be more or less likely to be associated with testosterone suppression. The present study was undertaken to validate the findings of the previous study by performing a similar analysis of pre- and post-treatment serum testosterone levels for a larger group of patients treated on an IRB-approved prospective study of hypofractionated proton therapy for localized prostate cancer.

Material and methods

Between April of 2008 and October of 2011, 228 patients with low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer were enrolled and treated according to a University of Florida Proton Therapy Institute (UFPTI) institutional review board-approved protocol.

For the purposes of the present analysis, three patients were excluded for receiving androgen deprivation therapy (n = 2) or testosterone supplementation (n = 1) before proton therapy. A pretreatment serum testosterone level was available for 217 of the remaining 228 patients. These 217 patients were included in the present analysis. Immediate post-proton therapy testosterone levels, obtained during the final week of treatment, were available for 207 patients. Testosterone levels at six and 12 months after proton therapy were available from 165 and 116 patients, respectively. Testosterone levels before treatment and at each interval after proton therapy were compared. No patient in this study reported taking exogenous testosterone supplements during proton therapy or the follow-up period. No patient received androgen deprivation therapy for a treatment failure during the follow-up period.

Of the 217 patients, 117 (54%) were treated for low-risk disease and 100 (46%) for intermediate-risk disease. Patients in the low-risk group were prescribed a dose of 70 cobalt Gray equivalent (CGE) to the prostate alone. Patients in the intermediate-risk group were prescribed a dose of 60 CGE to the prostate and proximal seminal vesicles (SV), with a 12.5 CGE boost to the prostate if normal tissue constraints allowed. Thus, all 117 patients in the low-risk group received a total dose of 70 CGE; 77 of the 100 patients in the intermediate-risk group received a total dose of 72.5 CGE, and 23 patients in the intermediate-risk group received a total dose of 70 CGE. All proton therapy sessions were delivered at 2.5 CGE per fraction using passively scattered protons. Overall, 205 patients were treated with one field daily using lateral or lateral oblique fields and 12 patients were treated with two fields daily. No patient received RT to the pelvic nodes.

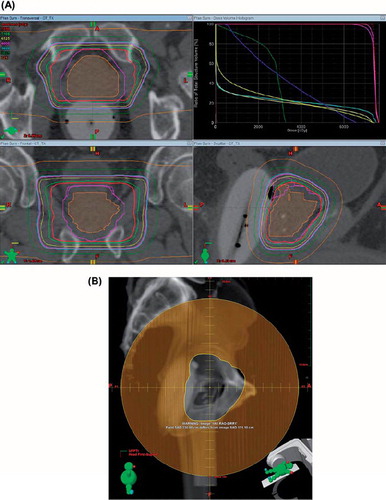

For target delineation, the contoured prostatic and, when applicable, the proximal seminal vesicle clinical target volume (CTV) corresponded to the gross tumor volume (GTV) without expansion. The planning target volume (PTV) expanded upon the CTV by 6 mm in the cranial, caudal and lateral directions and by 4 mm in the anterior and posterior directions. Typical proton therapy fields and dose distributions are shown in . Daily online KV imaging was utilized to position patients prior to each RT fraction.

Figure 1. (A) A typical treatment plan utilizing lateral or lateral oblique fields with an associated dose volume histogram. (B) A typical field aperture used to treat prostate and proximal seminal vesicles.

To evaluate the effect of proton dose and target volume, we separated the patients into three groups: 70 CGE to prostate only, 70 CGE to prostate + SV (reducing off the SV after 60 CGE), and 72.5 CGE to prostate + SV (reducing off the SV after 60 CGE). Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of age on the testosterone levels after proton therapy, we separated the patients into three age groups: <60 years (n = 53), 60–70 years (n = 121), and >70 years (n = 43).

The SAS and JMP statistical software programs (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) were used for all statistical estimations. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test for a non-zero difference between the pretreatment testosterone levels and each successive follow-up point. These same paired differences were further stratified by the strata of selected prognostic factors, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to detect any statistically significant differences.

Results

Pretreatment patient characteristics for of the 217 patients included in this analysis can be found in . The median follow-up for all patients was 2.0 years.

Table I. Pretreatment patient characteristics.

Compared with the baseline testosterone level before proton therapy, there were no significant changes at any follow-up point within one year after completion of proton therapy. The median testosterone level was 364.7 ng/dl (12.7 nmol/l) at treatment completion, 361.7 ng/dl (12.6 nmol/l) at six months, and 372.7 ng/dl (12.9 nmol/l) at 12 months after treatment ().

Figure 2. Testosterone values at each time interval are shown. The central line of the box is the median. The upper and lower edges of the box represent the 1st and 2nd quartiles of the data. The interior of the box includes the middle 50% of the data points.

Patients’ age at diagnosis did not affect testosterone levels after proton therapy. The mean testosterone levels before proton therapy stratified by age group were as follows: <60 years, 326.7 ng/dl (11.3 nmol/l); 60–70 years, 334.8 ng/dl (11.6 nmol/l); and >70 years, 406.2 ng/dl (14.1 nmol/l), not significant. There was no statistically significant difference between the pretreatment, immediate post-treatment, six- and 12-month follow-up levels after proton therapy in each age group (<60 years, not significant; 60–70 years, p = 0.4945; and >70 years, not significant).

All patients in the low-risk group (n = 117) received 70 CGE as planned. Of 100 patients in the intermediate-risk group, 77 patients were able to receive 72.5 CGE and 23 patients had a reduced prescription dose of 70 CGE to meet normal tissue constraints. Before proton therapy, the mean testosterone levels were 358.1 ng/dl (12.4 nmol/l) in the 70 CGE group and 326.7 ng/dl (11.3 nmol/l) in the 72.5 CGE group (not significant). The proton dose (70 vs. 72.5 CGE) had no effect on the testosterone levels after proton therapy compared with the pretreatment levels (at completion of proton therapy and then six and 12 months later, the p-value not significant).

The proton target volume (prostate only vs. prostate + SV) also had no effect on the testosterone level after proton therapy compared with the pretreatment level (at completion of proton therapy and then six and 12 months later, the p-value not significant). When we separated the patients into three groups, 70 CGE to prostate only, 70 CGE to prostate + SV (reducing off the SV after 60 CGE), and 72.5 CGE to prostate + SV (reducing off the SV after 60 CGE), there were no statistically significant differences in the post-treatment testosterone levels (at completion of proton therapy and then six and 12 months later).

Discussion

Declines in testosterone or dihydroxytestosterone levels have been reported after external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for prostate cancer [Citation6–10,Citation15]. Zagars et al. [Citation6] compared serum testosterone levels before and after prostate cancer patients received conventional pelvic EBRT to a median dose of 68 Gy (range 66–78 Gy). None of the patients received EBRT to the pelvic nodes. There was a median 16% decrease in serum testosterone levels at three months after completion of EBRT (p = 0.001).

Pickles et al. [Citation8] reported statistically significant drops in serum testosterone in patients with prostate cancer after RT. Although the vast majority of the patients received EBRT to the prostate only, testosterone after EBRT decreased to an average of 83% of pre-EBRT levels. Furthermore, 7.5% of patients experienced a decrease in testosterone greater than 50% of the baseline testosterone level. On multivariate analysis, radiation field size, radiation fraction size, and lower testosterone levels prior to radiation therapy were found to be a predictor for adverse changes in testosterone after pelvic EBRT.

Recently, Oermann et al. [Citation10] investigated serum testosterone levels in 26 men with low- or intermediate-risk prostate adenocarcinoma before and after hypofractionated stereotactic body RT (SBRT). The median age of the patients was 69 years (range 48–79 years). The prescription dose was 36.25 Gy in 5 fractions of 7.25 Gy over two weeks to the prostate or prostate and proximal SVs. The authors observed a 23.7% decline in total testosterone levels after hypofractionated SBRT. The authors determined that patients received a median dose of 2.1 Gy (range 1.1–5.8 Gy) to the testes from scattered radiation.

Daniell et al. [Citation15] compared serum testosterone level changes between patients treated with RT versus those treated with surgery. The authors found a 27.3% lower serum testosterone level in patients after pelvic EBRT than after radical prostatectomy. Other studies have also demonstrated declines in serum testosterone in men with pelvic malignancies undergoing pelvic EBRT [Citation16,Citation17].

In contrast to the above studies, Seal [Citation18] and Grigsby and Perez [Citation19] reported no changes in testosterone levels after pelvic EBRT (65–70 Gy). Both investigators, however, did find a significant decrease in dihydroxytestosterone and an increase in luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) after pelvic EBRT.

Due to anatomic proximity, it has been hypothesized that scattered radiation to the Leydig cells of the testes from pelvic EBRT would be correlated with decreased serum testosterone levels. Scatter dose to testes from the full course of conventional pelvic EBRT (68–70 Gy) for prostate cancer has been reported to be approximately 2 Gy [Citation6,Citation8,Citation20]. Recent IMRT data demonstrate a testicular dose ranging from 0.84 Gy with prostate-only treatment to 6.3 Gy with pelvic EBRT plus a prostate boost [Citation21].

Brachytherapy may be associated with a lower testicular dose than photon-based EBRT. The estimated testicular dose from scattered radiation was 19 cGy with I-125 implants in a study by Mydlo and Lebed [Citation22] and 2 cGy with Pd-103 implants in the study by Taira et al. [Citation23]. The latter group reported that patients who received primary brachytherapy did not experience declines in serum testosterone level after treatment [Citation23]. The authors suggest that the lower scattered dose to the testes would be the likely explanation for the lack of testosterone suppression. Interestingly, in the same study, men who received low-dose (20–45 Gy) supplemental pelvic EBRT after brachytherapy, as opposed to definitive pelvic EBRT doses of 70 Gy or higher, also did not experience a testosterone decline. The authors postulate that the relatively lower dose (20–45 Gy) of pelvic EBRT produced a lower scattered dose to the testes that was too low to cause a decline in serum testosterone levels.

The effect of scattered radiation on Leydig cell function may be age dependent with older men ostensibly being more likely to demonstrate Leydig cell injury from low-dose radiation than younger men [Citation24]. The available literature suggests a minimal change in testosterone levels after testicular irradiation in young men [Citation8,Citation25,Citation26]. Shapiro et al. [Citation26] examined alterations of testicular function in 27 men after EBRT for soft tissue sarcoma. The median age of patients in this study was 48 years. Radiation dose to the testes ranged from 0.01 to 25 Gy. The authors reported no changes in the serum testosterone levels at follow-up to 30 months. In contrast, the previously noted studies looking at older patients receiving photon-based EBRT for prostate cancer did demonstrate testosterone suppression.

While Hall argued that passively scattered proton irradiation would produce higher out-of-field neutron doses compared with IMRT [Citation27], his theory was based on the measurements performed at the original Harvard cyclotron, which is no longer in clinical use. Paganetti et al. [Citation28] questioned the applicability of these data to modern proton facilities. More importantly, Yoon et al. [Citation13] demonstrated that secondary neutron doses in a humanoid phantom produced by passively scattered protons in a contemporary facility is only about 10% of the secondary photon doses from IMRT for a prostate cancer patient. Other additional studies also show the low secondary neutron dose from scattering-mode proton delivery [Citation29,Citation30]. Furthermore, the secondary neutron doses can be controlled by the design of, and material used in, the proton beam line [Citation13,Citation29,Citation30].

In conclusion, hypofractionated passively scattered proton therapy for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients treated per a UFPTI protocol did not significantly impact serum testosterone levels within the 12 months after completing treatment. The findings of the present study are consistent with those of a previous study of conventionally fractionated passively scattered proton therapy from our institution. These two studies stand in contrast to the various studies demonstrating testosterone suppression in prostate cancer patients receiving photon-based EBRT. We believe that these two studies provide a biochemical validation of physics-based studies illustrating that proton therapy is associated with a low scatter dose to organs beyond the target and beam path.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Fractionation and protraction for radiotherapy of prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;43:1095–101.

- Duchesne GM, Peters LJ. What is the alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer? Rationale for hypofractionated high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;44:747–8.

- Brenner DJ. Toward optimal external-beam fractionation for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;48:315–6.

- Kupelian PA, Reddy CA, Klein EA, Willoughby TR. Short-course intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 GY at 2.5 GY per fraction) for localized prostate cancer: Preliminary results on late toxicity and quality of life. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;51:988–93.

- Kupelian PA, Reddy CA, Carlson TP, Altsman KA, Willoughby TR. Preliminary observations on biochemical relapse-free survival rates after short-course intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 Gy at 2.5 Gy/fraction) for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;53:904–12.

- Zagars GK, Pollack A. Serum testosterone levels after external beam radiation for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997;39:85–9.

- Segal RJ, Reid RD, Courneya KS, Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Prud’Homme DG, . Randomized controlled trial of resistance or aerobic exercise in men receiving radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:344–51.

- Pickles T, Graham P. What happens to testosterone after prostate radiation monotherapy and does it matter? J Urol 2002;167:2448–52.

- Tomic R, Bergman B, Damber JE, Littbrand B, Lofroth PO. Effects of external radiation therapy for cancer of the prostate on the serum concentrations of testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and prolactin. J Urol 1983;130: 287–9.

- Oermann EK, Suy S, Hanscom HN, Kim JS, Lei S, Yu X, . Low incidence of new biochemical and clinical hypogonadism following hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) monotherapy for low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:12.

- Mendenhall NP, Li Z, Hoppe BS, Marcus RB, Jr., Mendenhall WM, Nichols RC, . Early outcomes from three prospective trials of image-guided proton therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:213–21.

- Coen JJ, Paly JJ, Niemierko A, Weyman E, Rodrigues A, Shipley WU, . Long-term quality of life outcome after proton beam monotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:e201–9.

- Yoon M, Ahn SH, Kim J, Shin DH, Park SY, Lee SB, . Radiation-induced cancers from modern radiotherapy techniques: Intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:1477–85.

- Nichols RC, Jr., Morris CG, Hoppe BS, Henderson RH, Marcus RB, Jr., Mendenhall WM, . Proton radiotherapy for prostate cancer is not associated with post-treatment testosterone suppression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82:1222–6.

- Daniell HW, Clark JC, Pereira SE, Niazi ZA, Ferguson DW, Dunn SR, . Hypogonadism following prostate-bed radiation therapy for prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2001; 91:1889–95.

- Yoon FH, Perera F, Fisher B, Stitt L. Alterations in hormone levels after adjuvant chemoradiation in male rectal cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:1186–90.

- Yau I, Vuong T, Garant A, Ducruet T, Doran P, Faria S, . Risk of hypogonadism from scatter radiation during pelvic radiation in male patients with rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:1481–6.

- Seal US. FSH and LH elevation after radiation for treatment of cancer of the prostate. Invest Urol 1979;16:278–80.

- Grigsby PW, Perez CA. The effects of external beam radiotherapy on endocrine function in patients with carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol 1986;135:726–7.

- Boehmer D, Badakhshi H, Kuschke W, Bohsung J, Budach V. Testicular dose in prostate cancer radiotherapy: Impact on impairment of fertility and hormonal function. Strahlenther Onkol 2005;181:179–84.

- King CR, Maxim PG, Hsu A, Kapp DS. Incidental testicular irradiation from prostate IMRT: It all adds up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:484–9.

- Mydlo JH, Lebed B. Does brachytherapy of the prostate affect sperm quality and/or fertility in younger men? Scand J Urol Nephrol 2004;38:221–4.

- Taira AV, Merrick GS, Galbreath RW, Butler WM, Lief JH, Allen ZA, . Serum testosterone kinetics after brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:e33–8.

- Izard MA. Leydig cell function and radiation: A review of the literature. Radiother Oncol 1995;34:1–8.

- Rowley MJ, Leach DR, Warner GA, Heller CG. Effect of graded doses of ionizing radiation on the human testis. Radiat Res 1974;59:665–78.

- Shapiro E, Kinsella TJ, Makuch RW, Fraass BA, Glatstein E, Rosenberg SA, . Effects of fractionated irradiation of endocrine aspects of testicular function. J Clin Oncol 1985; 3:1232–9.

- Hall EJ. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, protons, and the risk of second cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:1–7.

- Paganetti H, Bortfeld T, Delaney TF. Neutron dose in proton radiation therapy: In regard to Eric J. Hall (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:1–7). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66:1594–5; author reply 5.

- Shin D, Yoon M, Kwak J, Shin J, Lee SB, Park SY, . Secondary neutron doses for several beam configurations for proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74: 260–5.

- Mesoloras G, Sandison GA, Stewart RD, Farr JB, Hsi WC. Neutron scattered dose equivalent to a fetus from proton radiotherapy of the mother. Med Phys 2006;33:2479–90.