Abstract

Background: Long-term treatment with antidepressants is considered effective in preventing recurrence of major depressive disorder (MDD). It is unclear whether this is true for primary care. Objectives: We investigated whether current guideline recommendations for long-term treatment with antidepressants in primary care are supported by evidence from primary care. Methods: Data sources for studies on antidepressants: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycInfo, Cinahl, articles from reference lists, cited reference search. Selection criteria: adults in primary care, continuation or maintenance treatment with antidepressants, with outcome relapse or recurrence, (randomized controlled) trial/naturalistic study/review. Limits: published before October 2009 in English. Results: Thirteen depression guidelines were collected. These guidelines recommend continuation treatment with antidepressants after remission for all patients including patients from primary care, and maintenance treatment for those at high risk of recurrence. Recommendations vary for duration of treatment and definitions of high risk. We screened 804 literature records (title, abstract), and considered 27 full-text articles. Only two studies performed in primary care addressed the efficacy of antidepressants in the long-term treatment of recurrent MDD. A double-blind RCT comparing mirtazapine (n = 99) and paroxetine (n = 98) prescribed for 24 weeks reported that in both groups 2 patients relapsed. An open study of 1031 patients receiving sertraline for 24 weeks, who were naturalistically followed-up for up to two years, revealed that adherent patients had a longer mean time to relapse.

Conclusions: No RCTs addressing the efficacy of maintenance treatment with antidepressants as compared to placebo were performed in primary care. Recommendations on maintenance treatment with antidepressants in primary care cannot be considered evidence-based.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder is a common illness. According to the WHO major depressive disorder will be one of the leading causes of disability worldwide by 2020, second only to ischaemic heart disease (Citation1). The high level of disability associated with depression is mainly caused by it's chronic or recurrent course (Citation2,Citation3). To prevent chronicity, relapses or recurrences after remission has been achieved during treatment of the acute episode, guidelines recommend long-term treatment with antidepressants (AD) (Citation4–6). Two recent meta-analyses based on a considerable number of placebo-controlled trials in which patients were randomized to either continuation of AD or placebo during the first three months after remission, have shown that continuation treatment with AD significantly decreases relapse rates within the first three months after randomization (Citation7,Citation8). This evidence supports the recommendation for continuation treatment with AD during the first months after remission to prevent relapse. Far less research has investigated the efficacy of longer-term maintenance treatment for prevention of recurrence (Citation7,Citation8). Although guidelines also recommend maintenance treatment with AD for several years, or even lifelong, for patients with previous recurrences the scientific basis for these recommendations is meagre, since only few studies have addressed the efficacy of AD in patients randomized more than three months after remission (Citation4–6,Citation8). For registration of an AD (e.g. by the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products), the manufacturer is required to provide efficacy data from placebo-controlled acute treatment studies as well as continuation studies lasting up to six months (http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/051897en.pdf).

The majority of patients with depression are treated in primary care (Citation9). One may assume that treatment of depression might not be that different between primary and secondary care, but without proof we cannot simply extrapolate the guidelines from secondary care to primary care. In addition, some studies did find, although small, differences between patients in primary and secondary care. For example, psychotic features and suicidality are less often present in primary care (Citation10). Primary care patients with depression seem to be less accepting of treatment, possibly leading to a lower effectiveness (Citation11). Furthermore, patients in primary care less often receive psychotherapy (Citation12). As the majority of studies of long-term AD treatment have been carried out in secondary care, their generalizability to primary care remains uncertain (Citation7,Citation8).

We sought to investigate the current depression guideline recommendations on long-term treatment with AD in primary care in order to determine if the recommendations are supported by studies representative of the primary care population. This review, therefore, addressed the following questions:

What is, according to current guidelines, the recommended duration of treatment with AD after remission for patients with major depressive disorder treated in primary care?

Are these recommendations for long-term treatment with AD in primary care supported by evidence from the literature?

Methods

Guideline recommendations

For the first question our aim was to collect current guidelines, from Europe and English-speaking countries in other parts of the world, which provided recommendations for primary care about AD treatment in major depressive disorders. Therefore, we searched PubMed, Cochrane, PsycInfo, Embase, Cinahl, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse as well as with the search machine Google with the keywords ‘depression’, ‘guideline’ and ‘treatment’. In addition, we searched the website of WONCA for links to primary care organizations in European countries; on the websites of these organizations we searched for depression guidelines. We excluded guidelines that were based on other guidelines and guidelines over 10 years old.

Studies on efficacy of long-term treatment with AD in primary care

For the second question, we used four systematic search strategies. First, we searched PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, Cinahl and the Cochrane library with keywords and free text words (see Appendix I). Articles written in English and published until October 2009 were included. We used the following inclusion criteria: participants: adult primary care patients (no children and not only elderly people aged >64 years); intervention: continuation or maintenance treatment with antidepressant agents in primary care; comparison: placebo or no comparison; outcome: relapse or recurrence of depression; study design: randomized controlled trial, controlled trial, open trial, clinical trial, naturalistic study, (systematic) review, all with a duration of at least six months. The search string in PubMed was as follows: Depressive disorder, major (Mesh) AND Antidepressive agents (Mesh) AND (‘Primary Health Care’ [Mesh] OR ‘Physicians, Family’ [Mesh] OR ‘Family Practice’ [Mesh] OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘general care’ OR ‘general health care’ OR ‘general practice’ OR ‘general practitioner’). In the other databases, we used comparable search strings.

In order to exclude the possibility that we might have missed articles with the chosen strategy, especially because not all primary care studies mentioned that they were performed in this setting, we did two additional searches in one database (PubMed) by adding the text word ‘depression’ and without all search terms referring to ‘primary care’, respectively. Either search did not reveal any additional paper. Third, we used the so-called ‘snowball method’ whereby we searched the reference lists of all retrieved articles for possible other relevant articles. Finally, we used Web of Science searching for articles citing the retrieved articles from our original search.

Data extraction

The search results were first screened on title and abstract for studies on long-term treatment with AD of major depressive disorder in primary care. All retrieved articles were obtained and the full text articles were read using the inclusion criteria described earlier.

Studies in specific groups of depressed patients (e.g. post-stroke depression, post-myocardial infarction depression), in children (aged less than 18 years) or the elderly (aged above 65 years) were excluded because depression course and response to AD can be different in these patients (Citation13–15). We excluded duplicates after retrieval of full text articles, because of practical reasons.

All searches were performed by the first author, who also did most of the title and abstract screening. She consulted the other authors in case she doubted about an article. Eventual full text article selection and data extraction was done during a meeting with all authors.

Results

Guideline recommendations for long-term treatment with AD in primary care

We collected 13 depression guidelines specifically addressing or at least mentioning treatment of depression with AD in primary care. An overview of the recommendations in the guidelines for the long-term treatment with AD in primary care is found in (Citation4–6,Citation16–25). Although all guidelines recommended continuation treatment with AD after remission for all patients, recommendations for duration of continuation treatment varied from 4 to 12 months. Maintenance treatment of varying durations (between 1 year and lifelong) was recommended for patients at high risk of recurrence, which each guideline defined differently. Almost all cited references in guidelines were based on studies carried out in secondary or tertiary care settings; most of these studies randomized patients within three months after remission and the difference between antidepressant and placebo was already achieved within three months after randomization (Citation4–6,Citation16–25). Relapse risk was 25% in the first year after remission, 42% after two years, 60% after five years and 50–85% after 15 years (Citation3,Citation26). The risk of relapse or recurrence increased after each subsequent episode (Citation26).

Table I. Guideline recommendations for long-term treatment with antidepressant of depression in primary care.

None of the guidelines specified whether recommendations for primary care should be different than those for secondary care and no guideline referred specifically to any controlled study performed in primary care.

Studies on efficacy of long-term treatment with AD in primary care

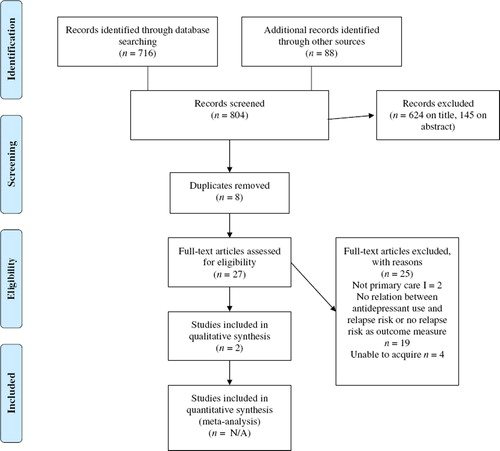

The database searches identified a total of 716 titles, including duplicates, because titles were retrieved in more than one database. Reference checking and the cited reference search rendered a total of 88 records. Screening titles and abstracts yielded 27 potentially relevant articles after removing duplicates (see ). Of these, 18 articles were excluded because they did not concern the efficacy of long-term treatment with AD in primary care or did not have relapse risk as an outcome measure; two studies were not performed (solely) in primary care; and one article, which was the only study from primary care frequently referred to in guidelines, proved to be a retrospective case-note-audit conducted in primary care, not addressing the relationship between AD use and relapse (Citation27). We were unable to acquire four articles. In summary, after reading the full-text articles, two publications remained (Citation28,Citation29). Neither of them was a placebo controlled study performed in primary care, which addressed the efficacy of AD in the prevention of relapse or recurrence in major depressive disorder.

Figure 1. Flow diagram. Source: Moher et al. (Citation31). For more information, visit http://www.prisma-statement.org

One study was an RCT involving 197 patients comparing the efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine (n = 99) and paroxetine (n = 98) during 24 weeks in patients with a major depressive episode. Only 91 patients (46.1%) completed the study, while remission was obtained in 35 patients (35%) receiving mirtazapine and 22 patients (22%) receiving paroxetine. After remission, in both groups 2 patients relapsed before the end of the study at 24 weeks. The authors did neither mention how many patients were actually followed after remission nor for how long (Citation28).

The second study involved 1031 primary care patients with DSM-IV major depression who had been participants in another study (Citation30). All patients were treated with sertraline for 24 weeks, which resulted in remission in 59% of patients. Patients (including non-remitters and non-responders) were naturalistically followed-up for up to two years. During this follow-up, the general practitioner made all decisions about treatment. Depression outcome was compared for patients who were adherent to treatment with AD versus non-adherent patients. Overall relapse or recurrence rates were not statistically different between groups, but adherent patients (mean time to relapse 302 days) had a longer mean time to relapse or recurrence than non-adherent patients (mean time to relapse 249 days) (Citation29).

Discussion

Our main findings are that the available guidelines do not specify that recommendations in primary care might be different from recommendations in secondary care with respect to continuation and maintenance treatment with AD. Moreover, there is a paucity of research investigating the efficacy of long-term treatment with antidepressants in primary care.

A limitation of this review is that we were unable to acquire all existing guidelines. Furthermore, we could not acquire all potentially interesting full text articles. Finally, we limited our search to articles published in the English language. The strength of this review is the comparison between guideline recommendations and evidence. Guidelines are used in everyday practice of primary care, and they are often thought to contain a high level of evidence. However, it is not always clear whether primary care guidelines are based on evidence from primary care.

Overall, guidelines recommend the continuation of treatment with AD for all patients for a period of four, nine or even 12 months. Maintenance treatment for a longer period, (i.e. between one year and lifelong) is recommended for patients at high risk of recurrence, which each guideline defines differently. However, the guidelines do not specify that recommendations are actually based on studies in secondary or tertiary care.

Our systematic search did not identify any placebo-controlled RCT to support the efficacy of continuation or maintenance treatment with AD in primary care. The two studies we found provided only circumstantial evidence suggesting that long-term treatment with AD can reduce relapse or recurrence rates (Citation28,Citation29). This raises the question on which studies the guidelines base their ‘level 1’ evidence. Guidelines refer to many studies with respect to optimal duration of treatment with AD after having achieved remission. In their recent meta-analysis of 30 placebo-controlled RCTs on long-term treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), Kaymaz et al. found a significant relapse-reducing effect of antidepressants compared to placebo at three, six, nine, as well as 12 months of follow-up. However, they also showed that the difference between antidepressant and placebo was achieved within three months after randomization, while no additional reduction in risk was observed at further follow-up (Citation8). With the exception of two very small trials including a total of 32 patients, there were no studies in which patients were randomized after three months of remission (Citation8). Thus, it can be concluded that the recommendations for the use of antidepressants in continuation treatment (i.e. during the first three to six months after remission to prevent relapse) are evidence based. However, good quality evidence is lacking for recommendations on the category of patients for whom maintenance treatment is appropriate, and on the duration of maintenance treatment. Furthermore, guideline recommendations for long-term treatment are only based on studies in patients treated in secondary care or specialized research settings and not for patients treated in primary care. Although one could argue that there are no strong arguments that recommendations on maintenance treatment with antidepressants in primary care should be different form secondary care, we conclude that they cannot be considered evidence-based. Hence, clinicians should be cautious with following the guidelines too strictly and instead may adjust the indication for long-term treatment to fit each patient's need. Finally, we conclude that further studies on the long-term treatment with antidepressants in primary care are warranted.

Conclusion

While depression guidelines recommend long-term (maintenance) treatment with antidepressants for both primary and secondary care patients with recurrent depressive episodes, it remains unclear whether these recommendations apply for patients in primary care.

Appendix I

Search strategy

In general

Title screening screened on:

Focus: Treatment with antidepressants and outcome of depression.

Type of study (if mentioned in title): Clinical trial; randomized controlled trial; observational/naturalistic study; review/meta-analysis.

Population (if mentioned in title): Not only elderly people, no children or adolescents, not people with (specific) comorbidity.

Abstract selection and eligibility criteria:

P: Primary care patients, adults (no children/adolescents, not only elderly people (>64 years of age)).

I: Continuation and/or maintenance treatment with antidepressant drugs in primary care.

C: Placebo other antidepressants or no comparison.

O: Relapse/recurrence of depression.

S: Study design: Randomized controlled trial; controlled trial; open trial; clinical trial; naturalistic study; (systematic) review. Duration at least six months.

Pubmed

Depressive disorder, major (Mesh).

Antidepressive agents (Mesh);

(‘Primary Health Care’ [Mesh] OR ‘Physicians, Family’ [Mesh] OR ‘Family Practice’ [Mesh]) OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘general care’ OR ‘general health care’ OR ‘general practice’ OR ‘general practitioner’.

Limits:

Searched until 1 October 2009.

Articles in English.

Ages 19–64.

PsycInfo

((DE ‘Major Depression’) and (DE ‘Antidepressant Drugs’))

((DE ‘Primary Health Care’ or DE ‘Primary Mental Health Prevention’) or (DE ‘Family Medicine’ or DE ‘Family Physicians’)) or (DE ‘General Practitioners’) or ‘primary care’ or ‘general practice’ or ‘general care’ or ‘family practice’.

Limits: 1900–2009 (until 1 October).

Language: English.

Only humans.

Adults (18 and older).

Cochrane

Depressive disorder, major (Mesh).

Antidepressive agents (Mesh).

(‘Physicians, Family’ [Mesh] OR ‘Family Practice’ [Mesh]) OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘primary health care’ [Mesh] OR ‘general practice’ OR ‘general health care’ OR ‘general care’ OR ‘general practitioner’.

No limits (searched on 29 October 2009).

All articles reviews published after 1 October 2009 were excluded, just like everything not in English, research on animals, or ages only younger than 18 or older than 64 (children or elderly people). Also economic evaluations were excluded.

Embase

‘Major depression’/exp AND ‘antidepressant agent’/exp.

‘Primary health care’/exp OR ‘family medicine’/exp OR ‘general practice’/exp OR ‘general practitioner’/exp OR ‘family physician’ OR ‘family practice’ OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘primary health care’ OR ‘general health care’ OR ‘general care’.

Limits:

Searched until 1 October 2009.

Articles in English.

Ages 18–64.

Embase only.

Explosion, free text.

Cinahl

(MH ‘Antidepressive Agents’.)

(MH ‘Depression’.)

‘General health care’ or (MH ‘Physicians, Family’) or (MH ‘Primary Health Care’) or ‘primary care’ or ‘family medicine’ or ‘general practice’ or ‘general practitioner’ and ‘general care’ or ‘family practice’.

Limits:

(Explode antidepressive agents and depression.)

Publication January 1900 until September 2009.

Language: English.

All adult.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist

Download PDF (131.6 KB)Declaration of interests: E Piek: none declared. K van der Meer: none declared.

WA Nolen: Grants: Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Glaxo SmithKline, Wyeth; Honoraria/Speaker's fee: Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Servier, Wyeth; Advisory boards: Astra Zeneca, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Glaxo SmithKline, Pfizer, Servier.

References

- WHO. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. France: WHO; 2001. Internet. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/index.html (accessed 1 Oct 2009).

- Shea MT, Elkin I, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT, Collins JF, . Course of depressive symptoms over follow-up. Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:782–7.

- Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, . Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1000–6.

- Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC, Cowen PJ, Howard L, Lewis G, . Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: A revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:343–96.

- Van Marwijk H, Grundmeijer H, Bijl D, Van Gelderen M, De Haan M, Van Weel-Baumgarten E, . NHG-standaard depressieve stoornis (depressie) (eerste herziening). Huisarts Wet. 2003;46:614–33.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression: Management of depression in primary and secondary care. Rushden: The British Psychological Society and Gaskell; 2007. Internet. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG23/Guidance/pdf/English (accessed 8 Feb 2008).

- Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, Furukawa TA, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, . Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: A systematic review. Lancet 2003;361:653–61.

- Kaymaz N, van OJ, Loonen AJ, Nolen WA. Evidence that patients with single versus recurrent depressive episodes are differentially sensitive to treatment discontinuation: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:1423–36.

- Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, . Use of mental health services in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;109:47–54.

- Vuorilehto MS, Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Isometsa ET. Do characteristics of patients with major depressive disorder differ between primary and psychiatric care? Psychol Med. 2007;37:893–904.

- Van Voorhees BW, Cooper LA, Rost KM, Nutting P, Rubenstein LV, Meredith L, . Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:991–1000.

- Powers RH, Kniesner TJ, Croghan TW. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in depression. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2002;5:153–61.

- Hayes D. Recent developments in antidepressant therapy in special populations. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:S179–85.

- Moreno C, Arango C, Parellada M, Shaffer D, Bird H. Antidepressants in child and adolescent depression: where are the bugs? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:184–95.

- Mueller TI, Kohn R, Leventhal N, Leon AC, Solomon D, Coryell W, . The course of depression in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;12:22–9.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie PuND. S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression. Berlin: DGPPN; 2009. Internet. Available from: http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de (accessed 5 Jan 2010).

- Heyrman J, Declercq T, Rogiers R, Pas L, Michels J, Goetinck M, . Depressie bij volwassenen: aanpak door de huisarts. Huisarts Nu. 2008;37:284–317.

- Bauer M, Bschor T, Pfennig A, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, . World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders in primary care. World J Biol Psychiatry 2007;8:67–104.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. ICSI Health Care guideline: Major depression in adults in primary care. Bloomington: ICSI; 2009. Internet. Available from: http://www.icsi.org/ (accessed 1 Oct 2009).

- Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. Bon usage des medicaments antidepresseurs dans le traitement des troubles depressifs et des troubles anxieux de l'adulte. Saint Denis: AFSSAPS; 2006. Internet. Available from: http://www.afssaps.fr (accessed 15 Oct 2009).

- Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale retningslinjer for diagnostisering og behandling av voksne med depresjon i primær- og spesialisthelsetjenesten. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2009. Internet. Available from: http://www.helsedirektoratet.no (accessed 15 Dec 2009).

- Landelijke stuurgroep richtlijnontwikkeling in de GGZ. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn DepressieHouten: Trimbos-instituut; 2005. Internet. Available from: http://www.cbo.nl/ (accessed 30 May 2008).

- Camden and Islington Mental Health. Depression guideline. London: Camden & Islington; 2003. Internet. Available from: http://www.cimh.info/ (accessed 14 Mar 2008).

- New Zealand Guidelines Group. Identification of common mental disorders and management of depression in primary care. Ministry of Health; 2008. Internet. Available from: http://www.nzgg.org.nz/ (accessed 1 Oct 2009).

- Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Cohen NL, Ravindran AV. Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. IV. Medications and other biological treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2001;46:38S–58S.

- Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, . Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:229–33.

- Wilson I, Duszynski K, Mant A. A 5-year follow-up of general practice patients experiencing depression. Fam Pract. 2003;20:685–9.

- Wade A, Crawford GM, Angus M, Wilson R, Hamilton L. A randomized, double-blind, 24-week study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine and paroxetine in depressed patients in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:133–41.

- Akerblad AC, Bengtsson F, von KL, Ekselius L. Response, remission and relapse in relation to adherence in primary care treatment of depression: a 2-year outcome study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:117–24.

- Akerblad AC, Bengtsson F, Ekselius L, von KL. Effects of an educational compliance enhancement programme and therapeutic drug monitoring on treatment adherence in depressed patients managed by general practitioners. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:347–54.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med- 2009;6:e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.