Abstract

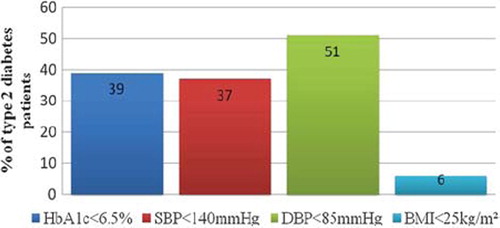

Objective: To assess glycaemic control among Estonian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) and to find patient and disease related factors associated with adequate glycaemic control. Methods: A cross-sectional study of 200 randomly selected DM2 patients from a primary care setting. Data on each patient's glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index, blood pressure, and medications for treatment of DM2 were provided by family doctors. A structured patient questionnaire was administered as a telephone interview (n = 166). The patients’ self-management behaviour, awareness of the HbA1c test and its recent value were inquired. Results: The mean HbA1c of the DM2 patients was 7.5%. The targets of DM2 treatment were achieved as follows: 39% of the patients had HbA1c below 6.5% and half the patients had HbA1c below 7%. More than third of the patients had systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg and in 51% of the patients diastolic blood pressure was below 85 mmHg. Six per cent of the patients were in normal weight (<25 kg/m2). Fifty-two per cent of the patients were aware of the HbA1c test and 36% of them knew its recent value. In multivariate regression analysis, awareness of the HbA1c test but not the HbA1c value, longer duration of diabetes and not having a self-monitoring device were independently associated with adequate glycaemic control (HbA1c< 6.5%).

Conclusion: The studied DM2 patients often did not reach the clinical targets suggested in the guidelines. Awareness of the HbA1c test was related to better glycaemic control. However, advanced stage of the disease had a negative effect on HbA1c.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) is a chronic disease with complex management and its complications place a heavy burden on the health care system (Citation1). Studies have demonstrated that poor glycaemic control is associated with more diabetic complications and an increased risk of death (Citation2,Citation3). Being overweight and having high blood pressure also contribute to vascular complications in diabetes (Citation4,Citation5). The best indicator of long-term glycaemic control is the serum glycosylated haemoglobin level (HbA1c). Despite the intensity of diabetes care, only a modest number of patients actually achieve the established targets of glycaemic control or reduction in vascular disease risk factors (Citation6–8). Patient related factors associated with poor glycaemic control include being female, overweight, having poorer health literacy and a longer duration of diabetes (Citation4,Citation9). Self-management behaviour, such as planned meals and physical activities, self-monitoring of blood glucose, and appropriate use of medications, are associated with better glycaemic control (Citation10). At the organizational level, case management and shared care interventions have shown improvements in glycaemic control (Citation11,Citation12). Different quality improvement strategies designed to improve glycaemic control are oriented towards organizational, clinician or patient behaviour change (Citation13). The above strategies are comprehensive and often too complicated to implement into routine practice. This suggests that we should remain open to evaluating the influence of other variables on glycaemic control.

HbA1c reflecting good glycaemic control should be one of the important targets for diabetes patients to reduce the risk of complications. Only a few studies have examined the effects of patients’ knowledge and understanding of HbA1c testing and its values, giving unexpected results (Citation14–16).

The aim of the present study was to assess glycaemic control among Estonian patients with DM2 and to determine patient and disease related factors associated with good glycaemic control.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study of 200 randomly selected type 2 diabetes patients from a primary care setting in Estonia. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Human Research of the University of Tartu.

Study participants

The study was conducted during 2004–2005. Our previous study (Citation17) had generated a list of 163 participants, representing 46% of the family doctors (FD) of Estonian Society of Family Doctors. We drew a random sample of 40 FDs from this list, of which 21 FDs agreed to participate in our study. Each FD provided us a coded list of their patients with DM2. We chose a different random starting point for every list and selected ten patients. All patients with DM2 were considered eligible irrespective of age, duration of diabetes, or treatment regimen. The FDs contacted the patients, and in case of agreement the patients were invited for a practice visit, or were visited at home, where they signed an informed consent. Ten patients were not included as they did not agree to participate in the study. When the patients’ HbA1c results were obtained, two researchers conducted a telephone interview. Data were obtained for 200 DM2 patients of whom 34 were not interviewed due to contact failure, death or change of residence. There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of the responders and the non-responders according to gender, mean age (64 versus 66 years) or mean glycosylated haemoglobin (7.5% versus 8%).

Measures

The FDs took a blood sample from each patient to determine HbA1c, measured each patient's height, weight, and blood pressure, and listed each patient's medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The recent value of total cholesterol was provided by the patients. The HbA1c, total cholesterol and blood pressure were assessed against the criteria in the Estonian DM2 Management Guidelines (2000), which was adapted from the European Diabetes Policy Group 1999. This defines good glycaemic control as HbA1c ≤ 6.5% (Citation18), good total cholesterol as ≤4.8 mmo/l, and well controlled blood pressure as ≤140/85 mm/Hg. These thresholds were also used in statistical analysis. Body mass index (BMI< 25 kg/m2 was defined as normal weight and subjects with BMI>27 kg/m2 were considered to have an additional risk factor for cardiovascular complications.

Questionnaire

The structured questionnaire used in the study had been compiled by our research team and piloted earlier. The questionnaire included forty-five items on patient and disease characteristics such as gender, age, urban or rural residence, duration of diabetes and treatment regimen. The following items were used as a proxy for good self-management behaviour: following the diet recommended for diabetes, adherence to medications as suggested, making changes to the treatment regimen, self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), frequency of practice visits during the past year and smoking status. The patients were asked about their awareness of the HbA1c indicator (or the ‘average three-month glucose test’) and those aware of the test were asked to recall its recent value. Most of the questions were in the form of multiple-choice questions providing two to six options.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using the statistical package SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science) 10.0 for Windows.

Means, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the continuous variables; mean and median were calculated for HbA1c (). The standard t-test was used to compare differences between the means. The paired samples t-test and the Spearman correlation coefficient were employed to compare differences in the self-reported and the measured HbA1c values. Frequency distribution was determined for all categorical variables. For comparison, the patients were dichotomized into groups according to the diabetes control HbA1c values ≤6.5% and > 6.5%.

Table I. Characteristics of the study subjects and their clinical outcomes (n= 200).

To determine the factors associated with good or poor glycaemic control, patient distributions were calculated using the chi-square test in terms of patient and disease characteristics, indicators of effective self-management behaviour, and awareness of the HbAc1 test. Additionally, estimation of the chance of good glycaemic control was analysed for the dichotomous variables with the odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval. To include all possible factors in the regression model, all factors differentiating at the P-value of 0.1 in Chi-square analysis were used as independent variables in the regression analysis, while other factors were omitted. Multinomial logistic forward stepwise regression analysis was used to predict good glycaemic control on the basis of the variables that proved significant in Chi-square analysis.

The purpose of the second model was to find associations between patients’ awareness of HbA1c on the one hand, and disease characteristics and self-management behaviour on the other hand. The distribution of the variables was tested with the Chi-square test to find significantly different factors in the regression model. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant in all other statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Sixty-one per cent of the patients were women and the distribution of the patients in urban and rural residence was similar (). The mean age of the female patients was 67.2 (SD ± 10.7) years and 61.0 (± 10.6) for the male patients (P <0.001).

Disease characteristics: treatment targets and patients’ awareness

HbA1c. Thirty-nine per cent of the patients met the HbA1c target of 6.5% set in the DM2 guidelines () and the test result for half the patients was below 7% (). Fifty-two per cent of the patients (n = 87) were aware of the HbA1c test and 36% of them were able to recall its recent value (). The mean of the self-reported HbA1c value (7.6% SD ± 2.5) and the mean of the measured value (7.5% SD ± 1.8) were analysed by the paired sample t-test, which yielded a good correlation (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.73 P = 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between the measured and the reported values (t-statistic –1.8 df 30, P = 0.08).

Cholesterol

Twenty-five per cent (n = 42) were able to report a recent value for their cholesterol level, wherein 16% of the respondents reported their cholesterol below 4.8 mmol/l. Mean self-reported cholesterol was 5.95 mmol/l (SD ± 1.4).

Other targets

Among the other targets of the DM2 guidelines, systolic blood pressure was normal in more than a third of the patients and diastolic blood pressure was normal for half of the patients. Six percent of the patients had normal weight defined as BMI 25 kg/m2 and ninety-nine percent of the patients had BMI over 27 kg/m2 ().

Treatment

Patient distribution according to treatment regimen was 14%, 70% and 16% for non-pharmacological treatment, for oral medication only and for oral medication combined with insulin, respectively. Patients reported good adherence to the doctor's recommendations; most of them took their medications constantly (94%) and did not smoke (84%). About half the patients (54%) reported that they had managed a special diet most of the time and one-fifth (21%) reported that they had changed the prescribed treatment regimen. The SMBG was used by a quarter of the patients (24%).

Factors associated with good glycaemic control (HbA1c<6.5%)

Comparison good or poor glycaemic control in terms of differences in the distribution of patient and disease related factors, self-management behaviour, and patient awareness of HbA1c showed that gender, smoking status, following the diabetes diet, number of visits made to a health care centre and reporting the result of the HbA1c test did not differ at a statistically significant level of 0.1 (). These factors were not included in the multinomial regression model.

Table II. Factors correlated with good glycaemic control (HbA1c<6.5%) in type 2 diabetes patients using the chi-square and logistic regression analysis.

Multinomial regression analysis found only three factors significantly associated with HbA1c ≤6.5%: not having a self-monitoring device; patients’ awareness of the HbA1c test; and diabetes duration of less than five years (). Whether the patient was able to recall a recent value of HbA1 was not an important factor in this model.

Table III. Factors associated with good glycaemic control (HbA1C <6.5%) versus poor control in multinomial forward stepwise regress ion analysis.

Predictors of patients’ awareness of the HbA1c test and knowledge of its recent value

None of the patient and disease characteristics or self-management behaviour characteristics was significantly different between the groups of patients who were aware of the HbA1c test or knew its result and those who did not.

Discussion

Targets of the DM2 guidelines

This is the first study assessing glycaemic control and other clinical targets against the criteria for the guidelines for type 2 diabetes patients from a general practice population in Estonia. Less than half (39%) the patients reached the recommended target of HbA1c <6.5%. Half the patients reached the other internationally used target of HbA1c <7%. Estonian DM2 patients from the specialist registry have been studied in 2001 (Citation19). The mean HbA1c in study by Vides was 7.3%, showing no significant change, but the mean of systolic blood pressure was higher (155 mmHg) when compared to our study. Estonian data are in line with several other studies from different countries reporting diabetes care in primary and specialist care settings among comparable demographics (Citation6, Citation8, Citation20–24). Usually the targets set in the guidelines for diabetes have not been reached but met shortfalls comparable to our findings even in better-funded health systems.

Awareness of clinical data

Doctors often see patient related factors as barriers that impede the following of recommendations from guidelines and the achievement of good glycaemic control (Citation25,Citation26). In the present study, out of all the numerous patient and disease related factors, patients who had awareness of the HbA1c test, did not possess a SMBG device and had diabetes for less than five years had higher chance of better glycaemic control. It was not important whether the patient knew their recent HbA1c value or not. Studies have demonstrated that patients’ awareness of the HbA1c test might be variable and even less of them were able to recall their test result or remembered it incorrectly (Citation14–16,Citation27). Half the DM2 patients in our study were aware of the HbA1c test, but only more than one third knew the exact value of their HbA1c, which was in good correlation with the measured value. This result is somewhat better compared to other studies conducted among DM2 patients (Citation15,Citation16). Patients who know their HbA1c value have been found to understand diabetes care better but this does not result in better measures of self-management behaviour (Citation14,Citation15).

Self-monitoring of blood glucose

Most of the factors related to patient self-management behaviour did not predict better glycaemic control in our study. The only exception among the proxies for self-management behaviour was the availability of a self-monitoring device, which was associated with poor glycaemic control. Evidently, contradiction regarding the fact that patients having a self-monitoring device and performing SMBG are more likely to have worse glycaemic control is due to the cause-and-effect relationship. Patients with advanced disease have a more complicated treatment regimen and probably have a greater need for need more SMBG. Furthermore, since the self -management supplies were not reimbursed by the state at the time of the study, patients may have thought it necessary to spend money on SMBG only in the later stage of the disease. It was demonstrated in a Dutch study that patients’ perception of poor glycaemic control rather than perception of good glycaemic control might stimulate them to use SMBG more often (Citation28). Still, there is no clear evidence that SMBG might be effective in improving glycaemic control in patients with DM2 (Citation29,Citation30). The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study showed that intensive treatment is more effective in lowering blood sugar when compared to conventional treatment. However, intensive treatment adds only limited benefits for advanced disease. In United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study of patients with diabetes for longer than five years, mean HbA1c of intensively treated group remain higher than that suggested in guidelines (Citation3). Patients with the advanced disease may adopt a more conscious attitude to self-management, adhering better to the doctor's recommendations. However, being more aware of the course of the disease and its complications might in turn increase the likelihood that patients evaluate their quality of life lower, as was demonstrated in our earlier study with the same participants (Citation31).

Knowledge is a prerequisite for better care, but efforts towards behavioural change are still needed. Recent evidence confirms that self-management programmes for diabetes mellitus and hypertension evidently produce clinically important benefits (Citation32–34). However, it is still difficult to determine which patient population could benefit the most as we did not find a correlation of any of the patient or disease related characteristics with better awareness of the HbAc1 test or knowledge of its results.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of our study is that the study subjects were selected randomly from FDs’ patient lists where rural and urban populations were equally represented. The study subjects’ mean age, gender, mean duration of diabetes and distribution of different treatment types are comparable to the corresponding characteristics of other studies (Citation8,Citation22,Citation24), which reflects the real situation of DM2 patients in a primary care setting.

The limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which allowed us merely to present associations but not causality. None the less, awareness of HbA1c may also be a proxy for other health-promoting variables, level of education attained, health-related values the patient has held from an early age, coping styles or trait self-efficacy. Since we did not measure these variables, we cannot say that awareness of HbA1c has an effect independent of these potential confounders. However, our results are still interesting and worthy of further study.

Implications

Overall, current data suggests that clinical trials, which often produce new targets for guidelines, can not be easily implemented into routine practice. Doctors might feel frustrated at having not achieved the targets set in guidelines, which often serve as equivalents for quality indicators and quality control. Some doubt still exists as to whether a more aggressive approach to DM2 patient care could lead to better outcomes in terms of mortality or cardiovascular events (Citation35–37).

Furthermore, doctors should not assume that their patients are aware of the HbA1c test and understand its meaning. Yet this could be an important issue for doctor-patient discussion because it is known that more frequent HbA1c measurements and immediate feedback are associated with better glycaemic control (Citation38,Citation39).

Finally, teaching self-management skills usually requires a very comprehensive programme and a lot of time. It is very important to point out the effective factor—awareness of HbA1c—which should be stressed when educating patients in a family practice. As the mean number of visits to health care professionals among our patients was quite high, one should use all possibilities, at least during short clinical appointments, to explore and enhance patient motivation and self-efficacy (Citation40).

Conclusion

The glycaemic control of the DM 2 patients did not adequately meet the targets set in the Estonian DM2 guidelines. Although awareness of the HbA1c test was higher than in previous reports and was related to better glycaemic control, the advanced stage of the disease had a negative effect on HbA1c. None of the specific patient and disease characteristics were associated with greater HbA1c awareness. Providing patients with information about how to manage glycaemic control is of primary importance as a part of a comprehensive strategy to increase patient motivation and quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The data presented in the current report were collected with the support of the Estonian Science Foundation grant No 6452, No 7596 and the targeted project SF 0180081s07 of the Estonian Ministry of Research and Education.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Sloan FA, Bethel MA, Ruiz D, Jr, Shea AM, Feinglos MN. The growing burden of diabetes mellitus in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:192–9.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group Lifetime Benefits and Costs of Intensive Therapy as Practiced in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. JAMA. 1996;276:1409–15.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352: 837–53.

- Bebb C, Kendrick D, Stewart J, Coupland C, Madeley R, Brown K, . Inequalities in glycaemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes in primary care. Diabetic Medicine 2005;22:1364–71.

- del Canńizo-Gómez FJ, Moreira-Andrés MN. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: Do we follow the guidelines? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2004;65: 125–33.

- Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA 2004;291:335–42.

- Kirk JK, Huber KR, Clinch CR. Attainment of goals from national guidelines among persons with type 2 diabetes: A cohort study in an academic family medicine setting. N C Med J. 2005;66:415–9.

- Spann SJ, Nutting PA, Galliher JM, Peterson KA, Pavlik VN, Dickinson LM . Management of type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting: A practice-based research network study. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:23–31.

- Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, . Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002;288:475–82.

- Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2001;24:561–87.

- The California Medi-Cal Type 2 Diabetes Study Group. Closing the gap: effect of diabetes case management on glycemic control among low-income ethnic minority populations: The California medi-cal type 2 diabetes study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:95–103.

- de Sonnaville JJ, Bouma M, Colly LP, Deville W, Wijkel D, Heine RJ. Sustained good glycaemic control in NIDDM patients by implementation of structured care in general practice: 2-year follow-up study. Diabetologia 1997;40:1334–40.

- Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, Grimshaw JM, Sundaram V, Rushakoff RJ, . Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: A meta-regression analysis. JAMA 2006;296:427–40.

- Wasserman J, Boyce-Smith G, Hopkins DS, Schabert V, Davidson MB, Ozminkowski RJ, . A comparison of diabetes patient's self-reported health status with hemoglobin A1c test results in 11 California health plans. Manag Care 2001;10:58–62,5–8,70.

- Harwell TS, Dettori N, McDowall JM, Quesenberry K, Priest L, Butcher MK, . Do persons with diabetes know their (A1C) number? Diabetes Educ. 2002;28:99–105.

- Heisler M, Piette JD, Spencer M, Kieffer E, Vijan S. The relationship between knowledge of recent HbA1c values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care 2005;28:816–22.

- Ratsep A, Kalda R, Oja I, Lember M. Family doctors’ knowledge and self-reported care of type 2 diabetes patients in comparison to the clinical practice guideline: Cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:36.

- IDF. A desktop guide to type 2 diabetes mellitus. European Diabetes Policy Group 1999. Diabet Med. 1999;16:716–30.

- Vides H, Nilsson PM, Sarapuu V, Podar T, Isacsson A, Schersten BF. Diabetes and social conditions in Estonia. A population-based study. Eur J Public Health 2001;11:60–4.

- Maney M, Tseng CL, Safford MM, Miller DR, Pogach LM. Impact of self-reported patient characteristics upon assessment of glycemic control in the veterans health administration. Diabetes Care 2007;30:245–51.

- Charpentier G, Genes N, Vaur L, Amar J, Clerson P, Cambou JP, . Control of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: A nationwide French survey. Diabetes Metab. 2003;29:152–8.

- Goudswaard AN, Stolk RP, Zuithoff P, Rutten GE. Patient characteristics do not predict poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes patients treated in primary care. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:541–5.

- Comaschi M, Coscelli C, Cucinotta D, Malini P, Manzato E, Nicolucci A. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects attending outpatient clinics in Italy: the SFIDA (survey of risk factors in Italian diabetic subjects by AMD) study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;15: 204–11.

- MacIsaac RJJG, Weekes AJ, Thomas MC. Patterns of glycaemic control in Australian primary care (NEFRON 8). Internal Medicine J. 2008;9999.

- Ratsep A, Oja I, Kalda R, Lember M. Family doctors’ assessment of patient- and health care system-related factors contributing to non-adherence to diabetes mellitus guidelines. Prim Care Diabetes 2007;1:93–7.

- Wens J, Vermeire E, Royen PV, Sabbe B, Denekens J. GPs’ perspectives of type 2 diabetes patients’ adherence to treatment: A qualitative analysis of barriers and solutions. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:20.

- Skeie S, Thue G, Sandberg S. Interpretation of hemoglobin A1c values among diabetic patients: Implications for quality specifications for HbA(1c). Clin Chem. 2001;47:1212–7.

- Klungel OH, Storimans MJ, Floor-Schreudering A, Talsma H, Rutten GE, de Blaey CJ. Perceived diabetes status is independently associated with glucose monitoring behaviour among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Prim Care Diabetes 2008;2:25–30.

- Farmer AJ, Wade AN, French DP, Simon J, Yudkin P, Gray A, . Blood glucose self-monitoring in type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13: iii–iv, ix–xi, 1–50.

- Welschen LM, Bloemendal E, Nijpels G, Dekker JM, Heine RJ, Stalman WA, . Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not using insulin: A systematic review. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1510–7.

- Kalda R, Rätsep A, Lember M. Predictors of quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Preference and Adherence 2008;2:21–6.

- Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, . Meta-analysis: Chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:427–38.

- Deakin T, McShane CE, Cade JE, Williams RD. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005: CD003417.

- Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: A systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1641–9.

- Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, . Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–59.

- McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT, Johnson JA. The effect of specialist care within the first year on subsequent outcomes in 24 232 adults with new-onset diabetes mellitus: population-based cohort study. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:6–11.

- Greenfield S, Billimek J, Pellegrini F, Franciosi M, De Berardis G, Nicolucci A, . Comorbidity affects the relationship between glycemic control and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetes. Ann Int Med. 2009;151:854–60.

- Anderson RM, Donnelly MB, Gorenflo DW, Funnell MM, Sheets KJ. Influencing the attitudes of medical students toward diabetes. Results of a controlled study. Diabetes Care 1993;16:503–5.

- Cagliero E, Levina EV, Nathan DM. Immediate feedback of HbA1c levels improves glycemic control in type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1999;22: 1785–9.

- Heisler M, Resnicow K. Helping patients make and sustain healthy changes: A brief introduction to motivational interviewing in clinical diabetes care. Clin Diabetes 2008;26:161–5.