Abstract

Background: For patients with respiratory tract infections evidence regarding bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise is sparse.

Objectives: To explore how general practitioners (GPs) in Poland and Norway would advise such patients.

Methods: Convenience samples of GPs in Poland (n = 216) and Norway (n = 171) read four vignettes in which patients presented symptoms consistent with pneumonia, sinusitis, common cold and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), respectively. For each vignette, GPs were asked whether they would recommend staying indoors, staying in bed and refraining from exercise, and if so, for how many days.

Results: For each vignette, the proportions of GPs recommending the patient to stay indoors in Poland versus Norway were 98% versus 72% (pneumonia), 92% versus 26% (sinusitis), 87% versus 9% (common cold) and 92% versus 39% (exacerbation of COPD). In regression analysis adjusted relative risks (95% CI) for recommending the patient to stay indoors in Poland versus Norway was 1.4 (1.2–1.5), 3.7 (2.8–4.8), 10.6 (6.3–17.7) and 2.5 (2.0–3.1), respectively. Among those who would recommend the patient to stay indoors, mean durations were 8.1, 6.6, 5.1 and 6.7 days in Poland versus 3.2, 2.8, 2.6 and 4.1 days in Norway, respectively. Polish GPs were also more likely to recommend staying in bed and refraining from exercise, and for a longer time, than their Norwegian colleagues.

Conclusion: GPs in Poland were more likely to recommend bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise. This suggests that they perceived the cases as more serious than their Norwegian colleagues.

KEY MESSAGE:

In a vignette study, GPs in Poland and Norway were asked whether they would advise patients with respiratory tract infections to refrain from exercise, stay indoors or stay in bed.

Compared to Norwegian GPs, the GPs in Poland were more likely to recommend such restrictions, and they tended to recommend these restrictions for a longer time.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with acute respiratory tract infections sometimes ask whether they should stay in bed, stay indoors or refrain from exercise. Evidence regarding benefits of such restrictions in daily life is sparse. Bed rest has been studied mostly for other conditions than respiratory tract infections (Citation1–4). If anything, bed rest has been shown to be harmful (Citation4). We are aware of no studies of bed rests or staying indoors in community dwelling patients with respiratory tract infections. In regard to exercise, studies of sports medicine suggest that heavy exertion may have detrimental effects on the immune system (Citation5) and increase the risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with pneumonia (Citation6). In upper respiratory tract infections, however, moderate exercise may not be harmful in terms of duration and severity of symptoms (Citation7,Citation8), and effects on the immune system may be beneficial (Citation5,Citation9,Citation10).

General practitioners (GPs) are often faced with questions that have no clear answers in terms of evidence based medicine (Citation11). In such cases, GPs may rely on intuition, experience, pathophysiologic rationale, patient preferences (Citation11–13), or even commonly held beliefs in the community (Citation14). Given that evidence is sparse; such factors are likely to be influential when GPs advise their patients regarding bed rest, staying indoors and exercise.

In a Polish study based on clinical vignettes, 94% and 74% of GPs would recommend bed rest for a patient with acute tonsillitis and sinusitis, respectively (Citation15). We are not aware of similar studies regarding exercise or staying indoors. However, in an observational study of GPs in Poland and Norway, Polish GPs were more likely to issue a sick leave note for patients with acute cough, and sick leave notes were issued for a longer time, even though the GPs in both countries recorded similar symptoms and signs (Citation16). We hypothesized that the Polish GPs perceived acute cough as more serious and wanted to protect their patients from physical stress. In the present study, we aimed to explore how GPs in Poland and Norway would advise patients with acute respiratory tract infections about bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise.

METHODS

In 2009, GPs attending continual medical educational (CME) courses and national meetings in Poland and Norway were approached and asked to participate in our survey. The content of the courses was unrelated to this study, but courses were chosen to ensure young as well as experienced participants. Further details about the recruitment of respondents have been reported elsewhere (Citation17).

For this study, we developed a questionnaire presenting four hypothetical patients, each with a different kind of acute respiratory tract infection. No specific diagnoses were mentioned, but the four case descriptions provided clues pertinent to pneumonia, sinusitis, common cold, and exacerbation of COPD, respectively (Citation17). We used symptoms as well as clinical findings as diagnostic triggers. In Norway, C-reactive protein (CRP) is often used in the diagnostic work-up of acute respiratory tract infections, whereas in Poland this is unusual. Consequently, blood tests were not included in our vignettes. The questionnaire was piloted for face validity among a few Norwegian colleagues, which resulted in minor adjustments. Translation and back-translation was undertaken by GPs in both countries to resolve ambiguities and to the extent possible ensure that Polish and Norwegian GPs were presented with identical vignettes.

For each vignette, we asked whether the GP would recommend the patient to stay in bed, stay indoors or refrain from exercise, and if so, for how many days. For other study purposes, GPs were asked about prescription of antibiotics, and whether they would issue a sick leave note (Citation17). Finally, questions about age, sex, speciality, years of professional experience, and workload were included. We collected no sensitive data or information that could be linked to the individual respondents. Return of completed questionnaires was regarded as consent.

For each of the four vignettes, we tested the hypothesis that Norwegian and Polish GPs would differ with respect to frequency and duration of recommended activity restrictions (bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise). Consequently, the proportion of GPs that would recommend restrictions and the recommended duration of these restrictions were our main outcome measures. The GPs’ country of residence was the main independent variable, whereas age, sex, speciality, number of years worked as a physician, and the average number of patients seen per hour were included as secondary independent variables. These secondary variables were included as possible confounders of potential associations between country of residence and frequency and duration of recommended restrictions, respectively.

Descriptive statistics (proportions, means) for frequency and duration of recommended restrictions, respectively, were calculated. We used log-Poisson regression with robust standard errors to calculate relative risks for recommending restrictions between the Polish and Norwegian samples. Ordinary least-squares regression was used to evaluate differences in mean duration of recommended restrictions. We used robust variance estimates to account for heteroscedasticity. SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) and STATA version 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas) were used for data analysis; P-values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The study was approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, which is the Data Protection Official for Research for all universities in Norway.

RESULTS

We obtained responses from 216 Polish and 171 Norwegian GPs, respectively. Compared with the Norwegian study arm, the proportions of women and specialists, respectively, were higher among the Polish respondents (). On average, the Polish respondents had longer working experience as physicians, and they reported seeing more patients per hour ().

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents in Poland and Norway.

Across the four vignettes, GPs in Poland were more likely to recommend bed rest and to stay indoors compared to GPs in Norway. For example, more than 85% of GPs in Poland would recommend the patients to stay indoors. Among GPs in Norway, this proportion was less than 40% in the different scenarios except for pneumonia (72%, ). With respect to exercise differences between Polish and Norwegian GPs were less pronounced. In multivariate regression analyses, differences in proportions recommending restrictions between Polish and Norwegian GPs were statistically significant except for refraining from exercise in the pneumonia and sinusitis scenarios, respectively (). Specialists in general practice were less likely to recommend bed rest than non-specialists in two scenarios (pneumonia: adjusted relative risk 0.8, P = 0.001, common cold: adjusted relative risk 0.6, P = 0.02). In addition, GPs with longer working experience were less likely to recommend bed rest (adjusted relative risk per year 0.990, P = 0.009) and less likely to advice against exercise in the pneumonia scenario (adjusted relative risk per year 0.996, P = 0.045). GPs seeing more patients per hour were more likely to recommend bed rest in the sinusitis scenario (adjusted relative risk per patient seen per hour 1.02, P < 0.001).

Table 2. Proportions of GPs that would recommend patients to stay in bed, stay indoors or refrain from exercise.

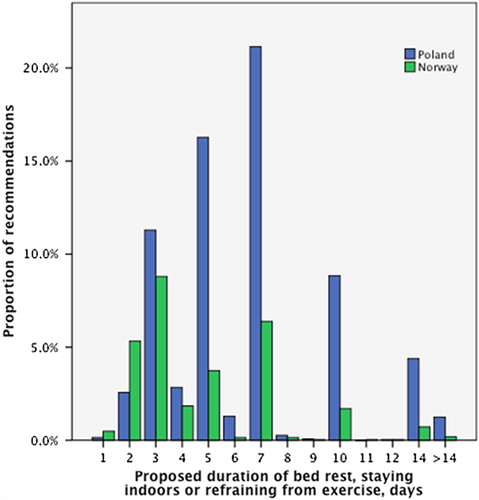

Among those who would recommend bed rest (GPs in Poland and Norway together), the mean proposed durations across the vignettes were 4.7 days (pneumonia), 4.9 days (sinusitis), 4.2 days (common cold) and 5.0 days (COPD exacerbations). Mean durations for staying indoors and refraining from exercise were 4.9 to 6.3 days, and 5.3 to 8.3 days, respectively. Across the four vignettes, Polish GPs tended to propose longer durations of the restrictions compared to Norwegian GPs (). Furthermore, there was considerable within country variation in the proposed duration of the restrictions (). Seeing more patients per hour was associated with recommending longer abstinence from exercise in the common cold and exacerbation of COPD scenarios (in both cases 0.1 days longer per patient seen per hour, P = 0.003 and P = 0.005, respectively).

Figure 1. Pooled distribution of proposed duration of bed rest, staying indoors and/or refraining from exercise. Each participant (n = 387) was asked for a recommendation regarding each type of restriction in four different cases of acute respiratory tract infections, i.e. 3 × 4 × 387 = 4644 recommendations. A duration was proposed in 57% (n = 1996) of these cases.

Table 3. Mean proposed duration (days) of bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise among GPs in Poland and Norway.a

DISCUSSION

Main findings

We found that 40–90% of GPs would recommend against exercise when presented with different hypothetical patients with acute respiratory tract infections. Recommendations to stay indoors and stay in bed were also common. Compared to Norwegian GPs, the GPs in Poland were more likely to recommend such restrictions, and they recommend restrictions for a longer time.

Relation to theory and other studies

Participants were faced with decisions under uncertainty, which involved both diagnosis and interventions. There are different theories for how physicians make such decisions. According to expected utility theory, GPs should aim to maximize desirable outcomes (i.e. utility in economic terms) (Citation18). To use this theory, however, the GPs would need to know probabilities and valuations of different outcomes that might follow from their recommendations. In fuzzy trace theory (Citation19), a core idea is that decision makers rely on the gist—i.e. the bottom line meaning—of information rather than the exact verbatim content. It is also conceivable that our respondents relied on clinical experience and intuition in their recommendations (Citation12). Studies in cognitive psychology indicate that experience and intuition often serve us well when making decisions (Citation20,Citation21), but sometimes lead us astray due to cognitive biases (Citation20,Citation22). Interestingly, in some cases we observed that experienced GPs and specialists in family medicine were less likely to recommend restrictions, whereas GPs seeing more patients per hour was more likely to do so. However, in regression analysis differences between GPs in Poland and Norway remained, when we adjusted for these factors. The observed differences between Polish and Norwegian GPs could be due to differences in perceived gist from our vignettes, i.e. that the Polish GPs perceived the patients’ condition as more serious than did their Norwegian colleagues. Butler et al., showed wide variation in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough across European countries, and in this study GPs from Poland were more likely to prescribe compared to Norwegian GPs (Citation23). Possible reasons for this variation were explored in a qualitative study, which included system factors such as lack of consistent guidelines and measures to reduce patient expectations for antibiotics (Citation24). Finally, cultural factors such as different folk models of respiratory tract infections might contribute to GPs’ decision making. In 1978, Helman described how GPs’ prescriptions and general advice to stay in bed, keep warm and take warm drinks tended to fit in with, and even reinforce such folk models in a suburb of London (Citation14). However, we are not aware of any studies to indicate whether the observed differences in the present study may be attributed to system factors or cultural factors as mentioned earlier.

Based on current knowledge about how the immune system responds to exertion, most participants probably did well in recommending against exercise for the patient with pneumonia and COPD exacerbation. This study concurs with Windak et al., (Citation15), who found that many GPs would recommend bed rest for upper respiratory tract infections. This may be questioned when considering harmful effects of bed rest (Citation4), as well as beneficial effects of moderate physical activity on the immune system (Citation5,Citation9,Citation10).

Strengths and limitations

This study is among the first to explore how GPs would advise their patients regarding bed rest, staying indoors or refraining from exercise when suffering from acute respiratory tract infections. The vignette technique ensured that physicians in Poland and Norway responded to identical clinical information. However, we realise that this study has several limitations. Our convenience samples may not be representative of GPs in Poland and Norway. Furthermore, even though we were able to adjust the observed differences between Polish and Norwegian GPs for several physician characteristics, the possibility of unmeasured confounders remains. Finally, there are concerns that decisions based on vignettes may not be representative of clinical practice. Vignette techniques, although often used, have not been extensively validated, but there are studies in support of their validity (Citation25). We do not know how often restrictions such as bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise are discussed in real life encounters. Due to time constraints and sparse evidence, it is conceivable that GPs do not initiate such discussions unless the patients ask. To the extent that such discussions are rare in general practice, the ecological validity of our findings may be limited.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, we conclude that GPs in Poland were more likely to recommend bed rest, staying indoors and refraining from exercise, and they recommended these restrictions for a longer time, compared to Norwegian GPs. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the GPs in Poland perceived case descriptions of acute respiratory tract infections as more serious than their Norwegian colleagues. Exploring this hypothesis further in qualitative studies might be interesting. Since there is limited empirical evidence pertaining to whether or when such restrictions should be recommended, clinical trials might be warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the participants for their time and effort.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The study was funded by the University of Tromsø, Norway (PAH, KW, HM) and the Medical University of Lodz, Poland (MG). The funding bodies had no involvement in the design of the study, data collection and interpretation, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

REFERENCES

- Meher S, Abalos E, Carroli G. Bed rest with or without hospitalisation for hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4: CD003514.

- Herkner H, Arrich J, Havel C, Müllner M. Bed rest for acute uncomplicated myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2: CD003836.

- Brower RG. Consequences of bed rest. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:S422–8.

- Allen C, Glasziou P, Del Mar C. Bed rest: A potentially harmful treatment needing more careful evaluation. Lancet 1999; 354:1229–33.

- Nieman DC. Current perspective on exercise immunology. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2:239–42.

- Duraković Z, Duraković MM, Skavić J, Duraković L. Physical exercise and cardiac death due to pneumonia in male teenagers. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:387–90.

- Weidner T, Schurr T. Effect of exercise on upper respiratory tract infection in sedentary subjects. Br J Sports Med. 2003; 37:304–6.

- Weidner TG, Cranston T, Schurr T, Kaminsky LA. The effect of exercise training on the severity and duration of a viral upper respiratory illness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30: 1578–83.

- Moreira A, Delgado L, Moreira P, Haahtela T. Does exercise increase the risk of upper respiratory tract infections?Br Med Bull. 2009;90:111–31.

- Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA. Exercise and respiratory tract viral infections. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37:157–64.

- Slowther A, Ford S, Schofield T. Ethics of evidence based medicine in the primary care setting. J Med Ethics 2004;30:151–5.

- Sherman M. Evidence-based common sense?Can Fam Physician 2008;54:166–71.

- Tracy CS, Dantas GC, Upshur RE. Evidence-based medicine in primary care: Qualitative study of family physicians. Br Med C Fam Pract. 2003;4:6.

- Helman CG.‘Feed a cold, starve a fever’—folk models of infection in an English suburban community, and their relation to medical treatment. Cult Med Psychiatry 1978;2:107–37.

- Windak A, Tomasik T, Jacobs HM, de Melker RA. Are antibiotics over-prescribed in Poland? Management of upper respiratory tract infections in primary health care region of Warszawa, Wola. Fam Pract. 1996;13:445–9.

- Godycki-Cwirko M, Nocun M, Butler CC, Muras M, Fleten N, Melbye H. Sickness certification for patients with acute cough/LRTI in primary care in Poland and Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:13–8.

- Halvorsen PA, Wennevold K, Fleten N, Muras M, Kowalczyk A, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. Decisions on sick leave certifications for acute airways infections based on vignettes: A cross-sectional survey of GPs in Norway and Poland. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29:110–6.

- Wulff HR. How to make the best decision: Philosophical aspects of clinical decision theory. Med Decis Making 1981;1:277–83.

- Reyna VF. A theory of medical decision making and health: Fuzzy trace theory. Med Decis Making 2008;28:850–65.

- Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. London: Penguin Books; 2012.

- Gigerenzer G, Goldstein DG. Reasoning the fast and frugal way: Models of bounded rationality. Psychol Rev. 1996;103: 650–69.

- Elstein AS, Schwartz A. Clinical problem solving and diagnostic decision making: Selective review of the cognitive literature. Br Med J. 2002;324:729–32.

- Butler CC, Hood K, Verheij T, Little P, Melbye H, Nuttall J, et al. Variation in antibiotic prescribing and its impact on recovery in patients with acute cough in primary care: Prospective study in 13 countries. Br Med J. 2009;338:b2242.

- Brookes-Howell L, Hood K, Cooper L, Little P, Verheij T, Coenen S, et al. Understanding variation in primary medical care: A nine-country qualitative study of clinicians’ accounts of the non-clinical factors that shape antibiotic prescribing decisions for lower respiratory tract infection. Br Med J Open 2012;2.

- Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Jain S, Hansen J, Spell M, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: A prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:771–80.