Abstract

Background: STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions)/START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment) criteria aim to identify potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) due to mis-, over- and under-prescription in older patients. Initially developed by Irish experts, their applicability has been demonstrated in primary health care (PHC).

Objective: To quantify and identify the most frequent PIM at PHC level using STOPP/START criteria. To identify factors that may modulate the onset of PIM.

Methods: Audit of a random sample of 272 electronic health records (including prescription, diagnosis and laboratory results) of patients ≥ 65 years old, with at least one prescription in the last three months, from a PHC setting in the Vigo Health Authority (Spain). Original STOPP/START criteria were used, as well as a version adapted to Spanish PHC. Descriptive statistics and generalized linear models were applied.

Results: The median number of medicines per patient was 5 (inter-quartile range: 3–7). The prevalence of PIM identified by the STOPP criteria was 37.5% and 50.7%, with the original criteria and the Spanish version, respectively. Using both versions of the START tool, the prevalence of under-prescription was 45.9% and 43.0%, respectively. A significant correlation was found between the number of STOPP PIM and number of prescriptions, and between the number of START PIM with Charlson comorbidity index and number of prescriptions. Of 87 criteria, 20 accounted for 80% of PIM.

Conclusion: According to STOPP/START criteria, there is a high level of PIM in PHC setting. To prevent PIM occurring, action must be taken.

KEY MESSAGES:

The higher the number of prescriptions, the greater the risk of potentially inappropriate medication according to STOPP/START criteria.

Omission of a prescription is more likely in patients with multimorbidity or with a higher number of prescriptions.

Of 87 STOPP/START criteria, 20 account for 80% of potentially inappropriate medication.

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate drug prescription for the elderly is essential for their safety. The World Health Organization has included adverse drug reactions (ADRs) among the 10 most important causes of death in the world, and a recent systematic review estimated the prevalence of ADRs to be 16.1% (Citation1). In Spain, a nationwide multicentre study in primary health care (PHC) concluded that 48% of ADRs were drug-related problems of which 58% were avoidable (Citation2).

Various factors contribute to the occurrence of ADRs among the elderly: higher morbidity and higher prevalence of chronic diseases, with the consequently higher number of simultaneous drug therapies and greater probability of drug interactions; age-related physiological changes, which alter the metabolism of some drugs making them more susceptible to causing side effects; and the very limited presence of this age group in clinical trials (Citation3).

Like the UK National Health Service, the Spanish public health care system has free universal coverage. It is decentralized into 17 Autonomous Communities. In the Autonomous Community of Galicia, the Servizo Galego de Saúde (Galician Health Service) serves 2 700 000 inhabitants with 398 health centres and 3141 general practitioners (GPs). It is organized into seven health authorities, each one a geographical and administrative entity.

The electronic health record (EHR) is common to both PHC and hospital settings and it records all information regarding diagnoses, diagnostic tests, hospital reports and prescriptions. All healthcare professionals have access to EHR, and 98% of the prescribing/dispensing is electronic. Everyone has an assigned GP, who acts as ‘gatekeeper’. Therefore, the GP, who is responsible for renewing prescription of chronic medications, is in the ideal position to understand and act amid the complexity of prescribing for older patients. Subsequently, there is considerable interest about potentially inappropriate prescription at this level of care.

Inappropriate prescribing can be defined as a situation in which the pharmacotherapy does not meet accepted medical standards and it may include under-, over- and mis-prescribing (Citation4). In the international literature, the most common tools for detecting potential inappropriate medication (PIM) use explicit based criteria established by expert consensus, followed by clinical judgment. Although, they require regular updating and local adaptation due to differences in the availability of medication and the prescribing patterns between countries, their greater inter-rater reliability and improved application time allow these criteria to be implemented with relative ease into daily clinical practice (Citation4,Citation5).

Among such criteria, the most popular is the American Beers’ criteria (Citation6). Some studies have highlighted limitations regarding the applicability of the Beers’ criteria in a European context (Citation7). This was one of the main reasons why in 2008 Gallagher et al., proposed a new set of explicit criteria: STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions)/START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment) (Citation8). These are European criteria, organized according to physiological systems and can quickly be applied in routine daily practice. The criteria are very sensitive in identifying potentially inappropriate medications and drug-induced harm, and also address the issue of under-prescribing potentially beneficial medications (Citation9). These criteria have already been applied successfully in various clinical scenarios, including PHC (Citation10,Citation11). Our research group has assessed the suitability of the criteria at this level of care using the RAND methodology and has proposed a modification (the AP2012 version) (Citation12).

To identify the most common PIM, is the first step in preventing adverse events. We, therefore, decided (a) to quantify the PIM in PHC within our health authority and to analyse the criteria that account for the highest proportion of inappropriate prescribing; and (b) to identify the patient variables that may influence its occurrence.

METHODS

Study design and setting

An observational cross-sectional study was designed using an audit of EHR.

The study was carried out at the PHC level within our health authority, which includes 53 health centres and 364 GPs. In 2011 the population served was 582 968 inhabitants (21.3% ≥ 65 years).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the audit, all patients ≥ 65 years of age, with at least one daily medication prescribed in the three months prior to the start of the study, were included. In addition, those who had died in the last three months, patients living in nursing homes and terminally ill patients were excluded.

Data collection and definition of variables

Two members of the research team using Excel carried out information extraction. If the EHR appeared to be incomplete, the paper clinical record was checked. When there was uncertainty about the interpretation of a criterion, the rest of the team was consulted. Data collection was carried out from June 2011 to October 2011.

Audit quality control was assessed by inter-observer concordance. The Kappa value for positive agreement of the STOPP criteria was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.72–0.92), and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.71–0.97%) for the START ones.

The variables considered were sex, age, diagnosis (coded with the International Classification for Primary Care, ICPC-2) and current medications (encoded with the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system); the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated and also included as a variable (Citation13–15).

Assessment of potentially inappropriate prescribing

Potentially inappropriate prescribing was assessed using the START/STOPP criteria, translated by Delgado et al., for Spain, as well as the AP2012 version (Citation8,Citation12,Citation16). In this modified version, the criteria excluded were ‘Bisphosphonates in patients receiving maintenance doses of oral corticosteroids’ and ‘Antiplatelets in diabetes mellitus (DM) if one or more major cardiovascular risk (CV) factors coexist.’ The criterion ‘Use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) outside their approved indications’ was included, and those criteria that only referred to warfarin were modified by adding acenocumarol, which is more commonly used in Spain.

Outcome variables

Outcome variables were: (a) Ratio of patients with at least one PIM according to STOPP or START criteria; (b) Number of PIM identified with STOPP or START criteria. These variables were assessed using the original STOPP/START criteria as well as the Spanish AP2012 version described earlier (Citation8, Citation12).

Sample size

For a population of 108 322, ≥ 65 years old, with an expected PIM prevalence of 23.0%, precision of 5% and a 95% confidence interval (CI), 272 EHR had to be reviewed (Citation10). Records were selected by simple randomized sampling with replenishment between the total number of patients ≥ 65 years served by the Servizo Galego de Saúde. A computer technician from outside the research team used Microsoft Excel 2003® to calculate the random numbers. To establish inter-observer consistency, a sample of 31 patients was used, calculated for a sample size of n = 272, with an expected agreement of 90%, an interval equal to ± 10 and a 95% confidence interval (Citation17).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included the ratio and standard deviation (SD), and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric variables.

Differences in distributions of categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney test was used to determine independence of two non-parametric variables.

To calculate relative risks (RR) of PIM and adjusted CI for each set of criteria, with number of STOPP PIM and number of START PIM per patient as outcome, generalized linear models (GLM) were applied. As the response variable is a count variable, it would be logical to use models with Poisson response, however, the variance of the variable is greater than the mean (over dispersion). Therefore, to obtain standard errors corrected for over-dispersion parameters, models with a Poisson response were replaced by negative binomial response models. The R statistical software (version 2.15.2) was used for the estimation of the function of the GLMs.

For the construction of the GLM model, initially a bivariate analysis was carried out with exposure variables and potential confounders. Subsequently, a multivariate analysis was undertaken including those independent variables that had a level of statistical significance lower than 0.2 in the bivariate analysis. In this model, the independent variables with a higher level of statistical significance were eliminated if they did not change the coefficients of the main variables of exposure by more than 10%, and if the Schwarz's Bayesian Information Criterion improved. All P values are two-sided, and the level of significance was set at P values of 0.05 or less.

Finally, the Pareto diagram was used to establish criteria that cover the highest weight of non-compliance with the prescription, presenting those that represent 80% of the PIM for each type of criterion and version.

Ethical considerations

A unique identification number was allocated to each patient to ensure confidentiality. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Clinical Investigation of Galicia (Cod. 2010/390).

RESULTS

A total of 65 medical records were excluded (48 without prescriptions, 7 deceased, 7 institutionalized, 3 terminal).

The study population included 60.6% (95% CI: 54.8–66.4) women and 39.3% (95% CI: 33.5–45.1) men. The median age was 76.0 (IQR: 71–81) years old and the median number of prescriptions per patient was 5 (IQR: 3–7). The median CCI was 1 (IQR: 0–2).

The prevalence of mis- and over-prescribing using the original criteria was 37.5% (95% CI: 31.7–43.2), and 50.7% (95% CI: 44.7–56.6) using the Spanish AP2012 version. The prevalence of under-prescribing was 45.9% (95% CI: 40.0–51.8) with the original criteria, and 43.0% (95% CI: 37.1–48.9) with the AP2012 version. In and , patients’ demographics and descriptive analysis are described in more detail.

Table 1. Patients’ demographics.

Table 2. Descriptive analysis.

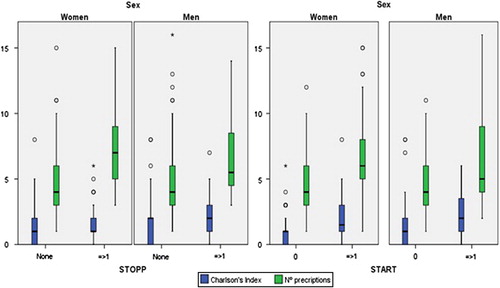

No significant differences in prevalence were found when applying each STOPP/START version. For both sets and versions of criteria, in the bivariate analysis, statistically significant differences were found between: (a) sex and age or CCI; (b) STOPP PIM and age or number of prescriptions; and (c) START PIM and age, number of STOPP criteria, CCI and number of prescriptions ().

The relationship between STOPP PIM and number of prescriptions was statistically significant using a GLM with both tools (original and Spanish AP2012 version). For START PIM the relationships with age and the number of prescriptions were statistically significant as was that with CCI, but to a lesser extent. The cut-off points are identified and shown in (CCI > 2 and number of prescriptions > 6).

Table 3. Multivariate regression model.

The most prevalent STOPP and START criteria of the two versions are compared (), with just 20 of 87 criteria representing the 80th PIM percentile. The most prevalent are STOPPGI6 (PPI not indicated), STARTMS3 (Calcium and Vitamin D supplement in patients with osteoporosis) and STARTEN3 (Antiplatelet therapy in DM with co-existing major CV risk factors).

Table 4. Criteria representing 80% of the potentially inappropriate medication by version.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The STOPP/START criteria constitute an easy to use tool for the detection of PIM. The prevalence found in PHC within our health authority varied, depending on the version used, between 37.5% and 50.7% for STOPP PIM and between 42.6% and 45.9% for START PIM.

The main difference between the original criteria and those adapted to PHC is marked by the inclusion of ‘Use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) outside their approved indications’ with a prevalence of 25%, and the exclusion of ‘Antiplatelet in DM if one or more major CVDR factors coexist’ with a prevalence of 9.9% when applying the original criteria, considered being an obsolete criterion in the AP2012 version (Citation12).

Strengths and limitations

The main limitations of the study stem from the use of EHR, because over-the-counter medication is not included, compliance is not assessed, incomplete records may exist, and the quality of the information contained in the EHR is not quantitatively evaluated by the Servizo Galego de Saúde. The quality of administrative data depends on the gaps in clinical information, coding procedures, and the billing context.

Despite the inter-observer concordance that is in agreement with that observed in research in other countries, interpreting certain criteria were difficult (Citation17–19). For example, when a patient with type 2 DM without renal failure and intolerance to metformin strictly would fail the criterion, but may need or be given another treatment; or for those START criteria relating to higher cardiovascular risk due to the use of antiplatelets or statins, in which the American Diabetes Association recommends secondary prevention strategies (Citation20). Hence, although not a major risk factor, having suffered a prior heart failure or stroke should be incorporated into the criteria. It is also difficult to interpret the use of a hypnotic or neuroleptic treatment in agitated patients with dementia without an assessment by the clinician. The criteria shown in are those that generated conflict or controversy in interpretation at the time of the audit, and our team strongly suggests that these should be discussed and modified in the next version.

Table 5. Controversial criteria.

The latest published evidence suggests new criteria that need to be agreed, such as adding zolpidem due to its association to fracture risk, or removing memantine associated with donepezil in moderate-severe Alzheimer's disease (Citation21,Citation22). Moreover, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) should be replaced by recently commercialized anticoagulants (Rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran) in patients intolerant to acenocoumarol.

In regard to the tool, the explicit criteria are reliable and easy to implement, but do not take into account the particularities of the health system (funding, co-payment) or the comorbidity of the patient (Citation9,Citation23). Therefore, clinical judgment is essential for each particular patient.

Lertxundi et al., highlighted the need to adapt the criteria to the market of each country and take into account the commercial novelties (Citation24). Therefore, the STOPP/START criteria have been adapted for use in specific countries (as in France), or to design their own lists (as in Norway, Germany and England), or guides (as in the Netherlands) (Citation18,Citation25–28).

Comparison with existing literature

A recent systematic review analyses PIM in PHC and estimates an average frequency of 19.1% (95% CI: 2.9–38.5%) in Europe (Citation3). This review includes studies mainly carried out with the Beers’ criteria, although one uses the STOPP/START criteria, with STOPP and START prevalence of 21.4% and 22.7%, respectively (Citation10). These values are lower than those reflected in this study. The differences may be due to the greater quantity of information recorded in the EHR in Servizo Galego de Saúde. ASA with cardiovascular risk was the most frequently omitted drug, followed by calcium and vitamin D supplements in osteoporosis, and statins in relation to the cardiovascular and endocrine system. Failure for the START criterion regarding calcium and vitamin D could be explained in patients with multiple comorbidities and medications, if such elements are provided in the diet. This coincides with our results.

Another study conducted in Ireland recorded a STOPP prevalence of 36% in a PHC setting; the most prevalent criteria were PPI at the maximum dose over eight weeks, followed by NSAIDs for more than three months, long-acting benzodiazepines and duplicate prescriptions (Citation11).

In Spain, Conejos et al., applied STOPP/START criteria in comparison with Beers’ criteria and detected a higher PIM with STOPP in the three settings analysed (PHC, hospital, nursing home care), with significant differences found between them in the START criteria (Citation29). Although using a convenience sample and eliminating some criteria, another study in PHC with the STOPP/START criteria detected 34.3% STOPP and 24.2% START prevalence, with results that were very similar to ours for the most common criteria (Citation30).

Ryan et al., correlated the over-prescribing type of PIM with the number of prescribed medications and age (Citation10). Nevertheless, they did not correlate the number of prescriptions with the prevalence of omission criteria. In this study, a correlation was found using GLM, which could be explained by the restraint on expanding the number of drugs prescribed to a patient when they are already taking a large number. This would also explain the correlation between CCI and START PIM (Citation31).

Implications for practice and future research

Results found, combined with the advantages in terms of easy application, make these criteria suitable for use in PHC practice, although the AP2012 version is more suitable for use, at least in Spain.

Hence, it is essential that the criteria are updated regularly. However, usage cannot replace the judgement of the clinician, who considers the complete clinical and holistic picture of a patient. The criteria should serve as a guide for detecting those patients who need to change their prescription or who need to be incorporated into other drug safety controls.

The STOPP/START criteria have been shown to reduce PIM in a clinical trial (Citation32). The association between STOPP PIM and preventable ADRs has recently been demonstrated (Citation33). In Spain, in older inpatients, 69% of ADRs have been reported to be related to PIM according to STOPP or Beers’ criteria, using the Naranjo algorithm (Citation34).

Future research should focus on involving a larger number of patients to confirm these results and analyse their clinical impact, such as software applications that alert clinicians or allow self-assessment (Citation4,Citation35,Citation36).

As in this study only a portion of the criteria represents 80% of the non-compliance cases, implementation of a shorter version using the most important parameters in our field to reduce application time is suggested. The intention is to carry out a study with a larger sample size in PHC to analyse the results obtained using this shorter version.

Conclusion

There are a high percentage of mis-, over- and under-prescription in PHC settings. As expected for the ≥ 65 years old group, multimorbidity and a high number of prescriptions were related to the occurrence of PIM.

The need to revise the STOPP/START criteria to fit the new evidence has been confirmed quantitatively as proposed in the AP2012 version, because 25% of patients have an inadequate PPI prescription, criteria are not covered in the original version.

Moreover, 20 of 87 criteria account for 80% of PIM, therefore, are prioritized for use in training and/or quality improvement activities.

FUNDING

The study received a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs in public competition, reference number EC 10/172.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Taché SV, Sönnichsen A, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence of adverse drug events in ambulatory care: A systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:977–89.

- APEAS study. Patient safety in primary health care. Madrid: Ministry of Health & Consumer Affairs; 2008.

- Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, De Rooij SE, Verheij R, Korevaar JC, et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e43617.

- Dimitrow MS, Airaksinen MS, Kivelä SL, Lyles A, Leikola SNS. Comparison of prescribing criteria to evaluate the appropriateness of drug treatment in individuals aged 65 and older: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1521–30.

- Chang CB, Chan DC. Comparison of published explicit criteria for potentially inappropriate medications in older adults. Drugs Aging 2010;27:947–57.

- Beers M. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 1991; 151:1825–32.

- Fialová D, Topinková E, Gambassi G, Finne-Soveri H, Jónsson PV, Carpenter I, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293:1348–58.

- Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J. STOPP (Screening tool of older person's prescriptions) and START (Screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46:72–83.

- Lam MPS, Cheung BMY. The use of STOPP/START criteria as a screening tool for assessing the appropriateness of medications in the elderly population. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012;5:187–97.

- Ryan C, O’Mahony D, Kennedy J, Weedle P, Byrne S. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish elderly population in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:936–47.

- Cahir C, Fahey T, Teeling M, Teljeur C, Feely J, Bennett K. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and cost outcomes for older people: A national population study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:543–52.

- Castillo-Páramo A, Pardo-Lopo R, Gómez-Serranillos IR, Verdejo-González A, Figueiras A. Assessment of the appropriateness of STOPP/START criteria in primary health care in Spain by the RAND method. SEMERGEN 2013;39:413–20. Spanish.

- Wonca. ICPC. International classification of primary care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987.

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. Oslo, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2012.

- Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

- Delgado Silveira E, Muñoz García M, Montero Errasquin B, Sánchez Castellano C, Gallagher PF, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Inappropriate prescription in older patients: The STOPP/START criteria. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2010;44:273–9. Spanish.

- Gallagher P, Baeyens JP, Topinkova E, Madlova P, Cherubini A, Gasperini B, et al. Inter-rater reliability of STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment) criteria amongst physicians in six European countries. Age ageing 2009;38:603–6.

- Lang P, Hasso Y, Belmin J, Payot I. STOPP-START: Adaptation of a French language screening tool for detecting inappropriate prescriptions in older people. Can J Public Health 2009;100: 426–31. French.

- Hernández Perella JA, Mas Garriga X, Riera Cervera D, Quintanilla Castillo R, Gardini Campomanes K, Torrabadella Fàbregas J. Inappropriate prescribing of drugs in older people attending primary care health centres: Detection using STOPP-START criteria. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2013;48:265–8. Spanish.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes 2012. Diabetes care 2012;35:S11–S63.

- Kolla BP, Lovely JK, Mansukhani MP, Morgenthaler TI. Zolpidem is independently associated with increased risk of inpatient falls. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:1–6.

- Rodda J, Carter J. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for symptomatic treatment of dementia. Br Med J. 2012;344: e2986.

- Gavilán Moral E, Villafaina Barroso A, editors. Polypharmacy and health: Strategies for therapeutic appropriateness. Barcelona: Reprodisseny; 2011. Spanish. Available at http://www.polimedicado.com (accessed).

- Lertxundi U, Peral J, Hernández R. Comments on the Spanish version of the STOPP/START criteria. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2011;46:170–1. Spanish.

- Rognstad S, Brekke M, Fetveit A, Spigset O, Wyller TB, Straand J. The Norwegian general practice (NORGEP) criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescriptions to elderly patients. A modified Delphi study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:153–9.

- Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: The PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Intl. 2010;107:543–51.

- Dreischulte T, Grant AM, McCowan C, McAnaw JJ, Guthrie B. Quality and safety of medication use in primary care: Consensus validation of a new set of explicit medication assessment criteria and prioritisation of topics for improvement. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2012;12:5.

- Vermeulen Windsant-van den Tweel AM, Verduijn MM, Derijks HJ, van Marum RJ. Detection of inappropriate medication use in the elderly; will the STOPP and START criteria become the new Dutch standards?Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A5076. Dutch.

- Conejos Miquel MD, Sánchez Cuervo M, Delgado Silveira E, Sevilla Machuca I, González-Blazquez S, Montero Errasquin B, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug prescription in older subjects across health care settings. Eur Geriatr Med. 2010;1: 9–14.

- Candela Marroquin E, Mateos Iglesia N, Palomo Cobos L. Adequacy of medication in patients 65 years or older in teaching health centers in Cáceres, Spain. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2012; 86:419–34. Spanish

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978;6:461–4.

- Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: A randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:845–54.

- Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O’Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1013–9.

- Fernández-Regueiro R, Fonseca-Aizpuru E, López-Colina G, Álvarez-Uría A, Rodríguez-Ávila E, Morís-De-La-Tassa J. Inappropriate drug prescription and adverse drug effects in elderly patients. Rev Clin Esp. 2011;211:400–6. Spanish.

- Martín Lesende I. Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: Clinical tools beyond the simple assessment. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2011;46:117–8. Spanish.

- Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6: CD000259.

- Fort I, Formiga F, Robles MJ, Regalado P, Rodríguez D, Barranco E. High prevalence of neuroleptic drug use in elderly people with dementia. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;134:101–6. Spanish.