ABSTRACT

Background: General practitioners (GPs) may play a crucial role in early recognition, rapid referral and intensive treatment follow-up of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). To improve early RA management, perceived barriers in general practice must be addressed. However, the general practice perspective on early RA management remains understudied.

Objective: To explore GPs’ experiences, beliefs and attitudes regarding detection, referral, and intensive treatment for early RA.

Methods: In 2014, a qualitative study was conducted by means of individual, in depth, face-to-face interviews of a purposive sample of 13 Flemish GPs. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and coded using the constant comparative method.

Results: GPs applied multiple assessment techniques for early RA detection and regularly prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if they suspected early RA. However, GPs felt unconfident about their detection skills because early RA symptoms are often unclear, diagnostic tests could provide inconclusive results and the incidence is low in general practice. GPs mentioned various approaches and multiple factors determining their referral decision. Perceived referral barriers included limited availability of rheumatology services and long waiting times. GPs considered intensive treatment initiation to be the expertise of rheumatologists. Reported key barriers to intensive treatment included patients’ resistance and non-adherence, lack of GP involvement and unsatisfactory collaboration with rheumatology services.

Conclusion: GPs acknowledge the importance of an early and intensive treatment, but experience various barriers in the management of early RA. GPs should enhance their skills to detect early RA and should actively be involved in early RA care.

General practitioners acknowledge the importance of early and intensive treatment but experience various barriers.

Barriers included low confidence in detection, limited accessibility in referral and poor professional collaboration in care.

General practitioners should enhance practical skills to detect early RA and should be actively involved in early RA care.

KEY MESSAGES:

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease affecting 0.8% of the population worldwide, with an estimated incidence of 29 cases per 100 000 in northern Europe (Citation1,Citation2). RA is characterized by chronic joint inflammation, if left untreated resulting in destruction and malformation of the joints and possibly leading to functional impairment and disability (Citation1). Treatment recommendations support an early and intensive treatment to control disease activity, reduce the progression of joint damage, maintain function, and improve the quality of life of patients with early RA (Citation3–5).

Early treatment, as soon as possible and ideally within the 12 weeks after symptom onset, may substantially decrease disability and increase the chance of achieving remission (Citation6,Citation7). Recent research, however, shows a median delay from symptom onset to treatment initiation ranging from 16 to 38 weeks in different countries (Citation8,Citation9). Raza et al., showed that delay in referral to a rheumatologist importantly contributed to the overall treatment delay in early RA (Citation9). They emphasized the need for a detailed understanding of the underlying reasons for this, depending on the local organization of healthcare, to reduce referral delay.

Initial intensive treatment strategies combining classical disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs with rapid remission inducing agents like glucocorticoids or biologicals are the most effective and safe option for patients with early RA in achieving the ‘window of opportunity’ to control the disease (Citation10–13).

General practitioners (GPs) may play a crucial role in the management of early RA since they are usually the first point of contact for the patient. It is primarily up to the GP to suspect early RA and to decide whether or not to refer to a rheumatologist (Citation14). Furthermore, they could play an important role in the follow-up of the early RA treatment as prescribed by the rheumatologists. Nevertheless, little is known about GPs’ interactions with patients with early RA and their experiences, beliefs and attitudes concerning the management of early RA (Citation15–18). Furthermore, to our knowledge, the beliefs and behavioural intentions of GPs about intensive treatment initiation remain unknown.

The aim of this study was to explore GPs’ experiences, beliefs and attitudes regarding the management of early RA, including detection, referral, and intensive treatment.

METHODS

Study design and sample

A descriptive, explorative study was conducted from January 2014 to September 2014 using individual, in-depth, face-to-face interviews with Flemish GPs. Individual interviews offered GPs the possibility to express beliefs, attitudes and experiences regarding early RA management and to discuss sensitive topics (Citation19).

We opted for purposive sampling to capture the entire spectrum of relevant experiences by pursuing a balanced male and female participation and heterogeneity regarding GP practice (). GPs were selected from a publicly available list with contact information of Flemish GPs (Citation20). Thirty-three GPs were contacted by telephone, received a brief introduction and they were invited for a face-to-face interview. Thirteen of those contacted gave oral consent. An appointment for an interview was scheduled at their place of work. Reasons for non-participation were a lack of time or dislike of interviews.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of Flemish GPs interviewed (n = 13)Table Footnotea.

Data collection

We developed an interview guide (Box 1) that was based on (a) literature on GPs’ experiences to early RA management and (b) previous interviews with rheumatologists, nurses and patients regarding intensive treatment strategies for early RA in Flanders (Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22). Two authors (JS and SM) conducted the interviews. The duration of the interviews ranged from 20 to 60 minutes and all interviews were audiotaped. Interviews continued until no new beliefs, attitudes and experiences emerged.

Analysis

The data collection and analysis were cumulative iterative. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and independently analysed and coded with software program NVivo 10 (QSR International Ltd) by two researchers (JS and SM). The qualitative analysis guide of Leuven, inspired by the constant comparative method of the grounded theory approach, was used to analyse the interview data (Citation23). JS and SM both read all of the transcripts, coded sections of text and set up an initial list of codes, which led to a broader range of identified codes. On a regular basis, the two researchers met to review the coding structure, ensuring the codes were applied in a consistent manner. Whenever there was a discrepancy, the specific passage was re-read and discussed until consensus was reached. The authors focused on retaining the verbatim meaning of the original wording in the translation of illustrative quotes. Throughout the analysing and coding process, anonymity of the GPs was guaranteed.

RESULTS

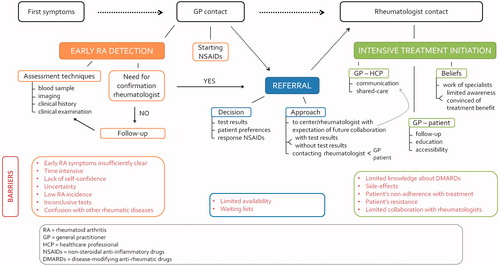

Data saturation was reached after after interviewing 13 GPs with no new information emerging from the final two interviews. Within the three domains of the management of early RA, GP experiences, beliefs and attitudes were explored, and the key findings are illustrated in . Each of these domains along with the barriers that GPs reported to experience are described in the next subsections and illustrated with quotes in Boxes 2, 3 and 4.

Box 1. Questions included in the interview guide.

Box 2. Examples of comment transcripts of general practitioners’ experiences, beliefs and attitudes regarding early rheumatoid arthritis detection.

Box 3. Examples of comment transcripts of general practitioners’ experiences, beliefs and attitudes regarding early rheumatoid arthritis referral.

Early RA detection

Assessment techniques

The assessment techniques mentioned for the detection of early RA were blood sampling, imaging, clinical history and examination, with blood sampling (rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibody, C-reactive protein and/or sedimentation rate) as the foremost mentioned. GPs stated that based on the clinical signs or symptoms, with or without a thorough examination, the additional availability of objective measures could provide a feeling of reassurance to take further steps in the detection process. A uniform finding amongst the GPs was the wish for their suspicion of early RA to be confirmed by a rheumatologist, regardless the strength of their suspicion.

NSAIDs prescription

Almost all GPs mentioned starting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if they suspected early RA (quote 1—GP10). Some GPs started with NSAIDs while referring immediately to a rheumatologist, whereas others put off the referral and first waited for the patient’s response to NSAIDs. In addition to NSAIDs, a minority of GPs prescribed food supplements or physiotherapy.

Barriers

GPs mentioned many perceived barriers to the detection of early RA. First, early RA was judged difficult to detect because the symptoms are often insufficiently specific. Consequently, GPs tended to think of early RA only when a patient already showed advanced joint inflammation. Moreover, GPs struggled with the fact that sometimes their suspicion of early RA needs time to evolve over several visits (quote 2—GP5). The next barrier was the lack of self-confidence GPs had in detecting early RA. Remarkably, GPs mentioned that they handled the detection process in their specific way while not being certain about the appropriateness. GPs doubted if the assessment techniques used and/or the prescription of anti-inflammatory drugs were appropriate. This uncertainty about early RA was attributed by the GPs to the low early RA incidence in their practice. Additionally, GPs were stuck with inconclusive diagnostic test results, especially inconclusive blood sampling (quote 3—GP3). A last cited barrier was the confusion with other rheumatic diseases such as osteoarthritis and gout.

Referral

Referral decision making

GPs mentioned three factors determining their referral decision. First, some GPs waited for indications of RA in blood tests or imaging, while others referred immediately, trying not to lose time (quote 4—GP11). Second, GPs considered the patient’s wish whether or not to be referred, even if this was contrary to their own belief about the need for referral. A last factor affecting the referral decision was the patient’s response to NSAIDs. Some GPs postponed the referral in case of a positive response to NSAIDs.

Referral approach

Different referral approaches amongst GPs were observed. Some GPs called the rheumatologist personally while others left it to the patients or their secretary to make an appointment. A second difference concerned the extent to which information was passed to the rheumatologist. While some GPs provided the rheumatologist with all test results, other gave greater importance to a rapid referral without providing them. Interestingly, GPs highlighted that the choice of centre for referral was influenced by the expected level of collaboration from the rheumatology team at the centre (quote 5—GP10).

Barriers

Two barriers related to the referral were outlined by some GPs. The first one was the limited availability of the rheumatologists by phone (quote 6—GP6). Once in contact, a second related barrier was the waiting time for an appointment. GPs identified this delay as frustrating for their patients and themselves because GPs perceived that patients want immediate help.

Intensive treatment initiation

GPs’ beliefs regarding intensive treatment

When asked about their beliefs regarding an intensive treatment initiation, almost all GPs answered seeing such treatment as a ‘specialist’s work’. However, when we subsequently asked them to state their conviction, some variation as to GP’s answers was noticed. Most GPs recognized the importance of intensive treatment (quote 7—GP5). Others showed limited awareness and remained neutral.

GPs’ perception of their roles in treatment

GPs mentioned the importance of collaboration with the rheumatology team consisting of a good communication and shared-care roles. Towards patients, GPs assigned themselves with a task including three elements. The first element was the follow-up of patients once they had visited a rheumatologist and started treatment. GPs wished to perform routine care during follow-up such as blood sampling, prescription of medication, motivating patients to continue medication intake and compliance checking, taking into account comorbidities. Second, most GPs saw it as their task to provide the patient with education about the disease and the treatment, for example about its chronic nature and the importance of early intensive treatment. Some GPs also considered the psychosocial support of patients with early RA as a task that has to be carried out by the GP. Finally, most GPs wanted to be accessible and perform emergency care, so that patients could come by quickly in case of a flare or a problem with medication (quote 8—GP8).

Barriers

Several barriers to intensive treatment initiation were put forward from the GPs’ perspective. A first one was the limited knowledge some GPs had about the disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Much more frequently mentioned were the side effects patients suffered from. Another barrier was the perceived patient’s non-adherence with the treatment, as a result of the side effects or paradoxically enough because there was a significant reduction in the symptoms of early RA (quote 9—GP8). A further barrier associated with the adherence was the perceived resistance of patients towards an intensive treatment strategy. Finally, the last barriers GPs experienced were limited shared-care arrangements and insufficient communication with rheumatologists and consequently, the feeling they lost their patient when referring to a rheumatologist. Losing patients due to rheumatologists entirely taking over patient care was frustrating for some GPs, because of the impossibility to supervise global healthcare for their patient.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

This qualitative study provides a better understanding of GPs’ experiences, beliefs, and attitudes regarding the management of early RA. GPs recognized the importance of rapid detection and initial intensive treatment included in most national and international recommendations for early RA management (Citation3–5). However, GPs experienced various barriers. Barriers included low confidence in detection, limited accessibility in referral and poor professional collaboration in care.

Strengths and limitations

A relatively high response rate (39%) was achieved. However, we cannot exclude that GPs who did not respond to the study invitation would have reported different experiences. The large proportion of GPs working in a group practice and the small sample size could limit the generalizability. Nevertheless, data saturation was achieved and the study findings are consistent with existing literature.

Comparison with existing literature

Pollard et al., report limited knowledge about early RA as a barrier to early RA detection (Citation15). One of the most critical findings of this study was not the lack of knowledge about early RA itself, but rather about how to act upon early RA detection. GPs rely on blood test results over clinical presentation while 40% of patients with early RA might be rheumatoid factor negative (Citation24). The challenge in general practice with a low incidence of early RA is to use assessment techniques that are useful for detection (Citation25). Similar to other qualitative studies, GPs’ uncertainty in identifying clinical characteristics was observed, mainly due to the mild and slowly progressive symptoms that are variable and often non-specific (Citation17,Citation26). The study of Stack et al., highlights that GPs need more understanding of early symptoms to distinguish early RA from other syndromes (Citation26). Verschueren et al., just as Garneau et al., already recognized the need to improve the comfort level of GPs and to facilitate the detection process in the early disease phase (Citation14,Citation27). Nowadays, the only postgraduate educational programme for GPs in Flanders is the patient partner programme, an educational initiative in which trained ‘expert patients with RA’ teach GPs practical skills to diagnose and manage early RA. For more than a decade, this programme has been incorporated in the training of medical students in Flemish universities.

Although some patients in Belgium consult a rheumatologist directly, most patients consult their GP first when seeking medical help. This is particularly the case for patients with vague and mild symptoms. The main factors influencing timely referral for early RA are clinical patient characteristics, patient preferences, access issues such as lack of timely appointments and availability of rheumatology services and GPs’ confidence and expectations regarding the collaboration with the rheumatologist (Citation17,Citation28). The long waiting times for appointments and the limited availability of rheumatologists should be addressed to reduce treatment delay.

Although GPs consider intensive treatment initiation as appropriate for early RA and belonging to the expertise of rheumatologists, several barriers are identified. The barriers about side effects, perceived patient’s resistance and non-compliance with the treatment are similar to those of rheumatologists prescribing an intensive treatment strategy (Citation21). Our findings show that GPs want to be involved, without taking over the rheumatologist’s tasks or entering their specialty. However, great variation exists in collaboration experiences. Suter et al., show that only 55–80% of all specialists communicated back to the GP (Citation17). Interestingly, GPs may change their referral approach when specialists fail to return the patients to them.

Implications for clinical practice and research

Future efforts are necessary to improve early RA detection by increasing the comfort level of GPs and subsequently to refer the right patient at the right moment to a rheumatologist resulting in decreased waiting times. The design of standardized, assessment techniques and computerized clinical decision support systems with clear and lean referral recommendations may help GPs identify patients requiring a specialist consultation (Citation29,Citation30). While assessment techniques can help GPs to detect early RA, a triage system could help rheumatologists to prioritize urgent referral (Citation31,Citation32). Once patients have started treatment, efforts need to be intensified to improve multidisciplinary early RA care. The persistent lack of communication and collaboration with specialized care could be ameliorated with a structured electronic communication platform. However, direct contact in person or by telephone must be feasible and should be preferred in some cases. Rheumatologists should communicate all important treatment information such as the treatment targets, the medication scheme, and what they expect from the GP during follow-up. In return, GPs should share all relevant background information about the patient. Moreover, care pathways have already been implemented in Flanders for different chronic diseases but still need to be developed for early RA (Citation33,Citation34).

Conclusion

GPs believe that early and intensive treatment is beneficial for patients with early RA. However, they experience multiple barriers. Barriers included low confidence in detection, limited accessibility in patient referral and poor professional collaboration. To improve early RA management in general practice, GPs should enhance practical skills for detection and should actively be involved in the early RA care.

Box 4. Examples of comment transcripts of general practitioners' experiences, beliefs and attitudes regarding intensive treatment initiation for early rheumatoid arthritis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the GPs who participated in this study for their time and openness during the interviews.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant from the Fonds voor wetenschappelijk reumaonderzoek/Fonds pour la recherche scientifique en rhumatologie. Patrick Verschueren is the holder of the Pfizer chair for early rheumatoid arthritis management at the KU Leuven and is supported by the Clinical Research Foundation of UZ Leuven, Belgium.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- van der Heijde DM. Joint erosions and patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34:74–8.

- Alamanos Y, Papadopoulos NG, Voulgari PV, Siozos C, Psychos DN, Tympanidou M, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006;36:182–8.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Nurmester G, Dougedos M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults (clinical guideline 79). London: NICE; 2009. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG79 (accessed 14 October 2014).

- Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:625–39.

- van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza K, van der Woude D, Knevel R, Huizinga TW et al. Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3537–46.

- Bosello S, Fedele AL, Peluso G, Gremese E, Tolusso B, Ferraccioli G. Very early rheumatoid arthritis is the major predictor of major outcomes: Clinical ACR remission and radiographic non-progression. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1292–5.

- De Cock D, Meyfroidt S, Joly J, Van der Elst K, Westhovens R, Verschueren P on behalf of the CareRA study group. A detailed analysis of treatment delay from the onset of symptoms in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;43:1–8.

- Raza K, Stack R, Kumar K, Filer A, Detert J, Bastian H, et al. Delays in assessment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Variations across Europe. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1822–5.

- Verschueren P, De Cock D, Corluy L, Joos R, Langenaken C, Taelman V, et al. Methotrexate in combination with Other DMARDs is not superior to methotrexate alone for remission induction with moderate to high dose glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis after 16 weeks of treatment: The CareRA trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:27–34.

- Goekoop‐Ruiterman Y, De Vries‐Bouwstra J, Allaart C, Van Zeben D, Kerstens P, Hazes J, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90.

- Verschueren P, De Cock D, Corluy L, Joos R, Langenaken C, Taelman V, et al. Patients lacking classical poor prognostic markers might also benefit from a step-down glucocorticoid bridging scheme in early rheumatoid arthritis: Week 16 results from the randomized multicenter CareRA trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:97.

- Raza K, Filer A. The therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis: Does it ever close? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:793–4.

- Garneau KL, Iversen M D, Tsao H, Solomon DH. Primary care physicians’ perspectives towards managing rheumatoid arthritis: Room for improvement. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R189.

- Pollard LC, Graves H, Scott DL, Kingsley GH, Lempp H. Perceived barriers to integrated care in rheumatoid arthritis: Views of recipients and providers of care in an inner-city setting. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:19.

- Rat AC, Henegariu V, Boissier MC. Do primary care physicians have a place in the management of rheumatoid arthritis? Joint Bone Spine 2004;71:190–7.

- Suter LG, Fraenkel L, Holmboe ES. What factors account for referral delays for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:300–5.

- Laires PA, Mesquita R, Veloso L, Martins AP, Cernadas R, Fonseca JE. Patient’s access to healthcare and treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: The views of stakeholders in Portugal. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:279.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; 2008.

- Huisartsen. Available at http://www.mediwacht.be (accessed 21 September 2014).

- Meyfroidt S, van Hulst L, De Cock D, Van der Elst K, Joly J, Westhovens R, et al. Factors influencing the prescription of intensive combination treatment strategies for early rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2014;42:265–72.

- Meyfroidt S, Van der Elst K, De Cock D, Joly J, Hulscher M, Westhovens R, et al. Patients’ experiences with intensive combination treatment strategies for early rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:384–90.

- Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C, Bryon E, Denier Y. QUAGOL: A guide for qualitative data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:360–71.

- Barra L, Bykerk V, Pope JE, Haraoui BP, Hitchon CA, Thorne JC, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and rheumatoid factor fluctuate in early inflammatory arthritis and do not predict clinical outcomes. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1259–67.

- Irving G, Holden J. The time-efficiency principle: Time as the key diagnostic strategy in primary care. Fam Pract 2013;4:386–9.

- Stack R, Llewellyn Z, Deighton C, Kiely P, Mallen C, Raza K. General practitioners’ perspectives on campaigns to promote rapid help-seeking behaviour at the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:37–43.

- Verschueren P, Esselens G, Westhovens R. Daily practice effectiveness of a step-down treatment in comparison with a tight step-up for early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2008;47:59–64.

- Bernatsky S, Feldman D, De Civita M, Haggerty J, Tousignant P, Legaré J, et al. Optimal care for rheumatoid arthritis: A focus group study. Clin Rheumatol 2010;29:645–57.

- Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J Am Med Assoc 2005;293:1223–38.

- Thorsen O, Hartveit M, Baerheim A. General practitioners’ reflections on referring: An asymmetric or non-dialogical process? Scand J Prim Health Care 2012;30:241–6.

- Robinson PC, Taylor WJ. Time to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Factors associated with time to treatment initiation and urgent triage assessment of general practitioner referrals. J Clin Rheumatol 2010;16:267–73.

- van Nies JA, Brouwer E, van Gaalen FA, Allaart CF, Huizinga TW, Posthumus MD, et al. Improved early identification of arthritis: Evaluating the efficacy of Early Arthritis Recognition Clinics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1295–301.

- Vanhaecht K, Panella M, Van Zelm R, Sermeus W. An overview on the history and concept of care pathways as complex interventions. Int J Care Pathw 2010;14:117–23.

- Van Houdt S, Heyrman J, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, De Lepeleire J. Care pathways across the primary-hospital care continuum: Using the multi-level framework in explaining care coordination. BMC health serv res 2013;13:1–12.