Abstract

Background — Metal-on-metal (MOM) total hip arthroplasties were reintroduced because of the problems with osteolysis and aseptic loosening related to polyethylene wear of early metal-on-polyethylene (MOP) arthroplasties. The volumetric wear rate has been greatly reduced with MOM arthroplasties; however, because of nano-size wear particles, the absolute number has been greatly increased. Thus, a source of metal ion exposure with the potential to sensitize patients is present. We hypothesized that higher amounts of wear particles result in increased release of metal ions and ultimately lead to an increased incidence of metal allergy.

Methods — 52 hips in 52 patients (median age 60 (51–64) years, 30 women) were randomized to either a MOM hip resurfacing system (ReCap) or a standard MOP total hip arthoplasty (Mallory Head/Exeter). Spot urine samples were collected preoperatively, postoperatively, after 3 months, and after 1, 2, and 5 years and tested with inductively coupled plasma-sector field mass spectrometry. After 5 years, hypersensitivity to metals was evaluated by patch testing and lymphocyte transformation assay. In addition, the patients answered a questionnaire about hypersensitivity.

Results — A statistically significant 10- to 20-fold increase in urinary levels of cobalt and chromium was observed throughout the entire follow-up in the MOM group. The prevalence of metal allergy was similar between groups.

Interpretation — While we observed significantly increased levels of metal ions in the urine during the entire follow-up period, no difference in prevalence of metal allergy was observed in the MOM group. However, the effect of long-term metal exposure remains uncertain.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the articulations of hip implants were mainly metal-on-metal (MOM). The implants released cobalt, chromium, and nickel, which could be found in high levels in the blood, hair, and urine (Coleman et al. Citation1973, Benson et al. Citation1975, Elves et al. Citation1975, Gawkrodger Citation2003). Furthermore, the patients became sensitized to the metals released and an association with early loosening was observed (Coleman et al. Citation1973, Benson et al. Citation1975, Elves et al. Citation1975, Gawkrodger Citation2003, Jacobs et al. Citation2009). Gradually, MOM implants were abandoned and the work by Sir John Charley with the metal-on-polyethylene (MOP) bearing advanced hip replacement substantially. However, the MOM articulation was reintroduced in the 1990s, as it became clear that polyethylene debris caused osteolysis, which was a significant clinical issue—especially in young and active patients (Marshall et al. Citation2008). The MOM Hip Resurfacing System has been proposed to have advantages such as enhanced longevity (Chan et al. Citation1999, Sieber et al. Citation1999, Firkins et al. Citation2001), enhanced implant fixation (Grigoris et al. Citation2006), lower dislocation rate (Scifert et al. Citation1998), better reproduction of hip mechanics, and more native femoral shaft bone stock left for revision surgery (Shimmin et al. Citation2008).

MOM articulations have greatly reduced the volumetric wear rate of hip prostheses; however, because of nano-sized metal wear particles, the absolute number of wear particles has greatly increased (Doorn et al. Citation1998, Chan et al. Citation1999, Sieber et al. Citation1999, Firkins et al. Citation2001, Rieker and Kottig. Citation2002). Also, Hallab et al. (Citation2004) suggested that the prevalence of metal allergy could be higher in patients with implant failure. In both cases, a source of metal ion exposure with the potential to sensitize patients is present, but the long-term biological effect of the metal wear debris remains unknown.

Metal hypersensitivity is a well-established phenomenon and is common, affecting about 10–15% of the general population (Thyssen and Menne Citation2010). Metal allergy can develop after prolonged or repeated cutaneous exposure to metal, usually from consumer products. Affected individuals typically suffer from allergic contact dermatitis and react with cutaneous erythema, papules, and vesicles after skin contact. This reaction is categorized as a type-4 T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Also, metal hypersensitivity may develop following internal exposure to metal-releasing implants. Theoretically, metal hypersensitivity could lead to a powerful reaction to prosthesis implantation (Pandit et al. Citation2008).

We hypothesized that an increased number of wear particles from MOM hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) would lead to increased blood levels and urinary excretion of metal ions, and ultimately to an increased prevalence of metal allergy.

Patients and methods

Study design, patients, and implants

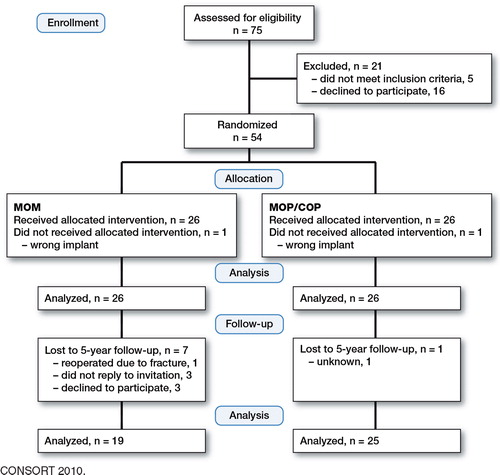

The study was added secondary to a randomized clinical trial (Petersen et al. Citation2011) with the following inclusion criteria: (1) primary osteoarthritis, (2) acceptable bone quality to allow the insertion of a HRA, (3) no regular intake of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and (4) age between 50 and 65 years at the time of surgery. At 5-year follow-up, patients were excluded if (a) they had received other metallic implants, (b) they had had occupational exposure to chromium, cobalt, or molybdenum, (c) they had taken (ingested) medication containing chromium, cobalt, or molybdenum, or (d) they had kidney disease. 54 patients were included in the study and were allocated to 1 of 2 treatment modalities: the metal-on-polyethylene/ceramic-on-ceramic (MOP/COP) group or the metal-on-metal (MOM) group (). The MOP group received a hybrid implant consisting of a cemented Exeter stem (Stryker) and a cementless porous-coated Mallory Head acetabular shell (Biomet). The modular femoral head was ceramic (Alumina; Stryker) in 15 patients and stainless steel (Orthinox; Stryker) in 10 patients. The MOM group received a ReCap Hip Resurfacing System (Biomet) consisting of a cemented cobalt-chromium femoral component and a cementless titanium, non-hydroxyapatite-coated, closed pore porous-coated acetabular component with a cobalt-chromium core fixed by press fit. In both groups, the femoral component was fixed with low-viscosity Simplex P bone cement with Tobramycin (Stryker). All patients were operated by 2 senior orthopedic surgeons at Silkeborg Regional Hospital or Aarhus University Hospital between January 2005 and August 2007. The patients were block-randomized with 10 patients in each block (5 MOM and 5 MOP/COP). Randomization took place on the day before surgery where the code was broken by the surgeon. The patients were first informed about the implant type postoperatively. In both groups, the posterior surgical approach was used but in the MOM group a small detachment of the gluteus maximus insertion was performed. Results from this trial up to 2 years have already been published (Baad-Hansen et al. Citation2011, Petersen et al. Citation2011). All patients (n = 54) were alive at 5 years. They were invited by letter to an additional and more extensive 5-year follow-up, and 44 patients participated (). Data were used until dropout.

Table 1. Patient demographics and characteristics

All participants signed an informed consent document before the 5-year examination. The 5-year follow-up was approved by the Central Denmark Region Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (study number: M-20110038; date: February 24, 2011) and registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (study number: 2007-58-0010; date: March 30, 2011). Furthermore, the study was registered at Clinical Trials (study number: NCT 00116948; date: June 30, 2005) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (II). The full trial protocol can be accessed at the Central Denmark Region Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics.

The data collection in this manuscript involved (1) spot urine samples collected preoperatively, postoperatively, at 3 months, and at 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years for testing with inductively coupled plasma-sector field mass spectrometry, (2) hypersensitivity to metals evaluated with patch test and lymphocyte transformation assay, and 3) a questionnaire about hypersensitivity.

Analysis of urine for metals

Spot urine samples from first morning void were collected in metal-free 30-mL high-density polyethylene containers from a urine-collection kit. The patients were asked to wash the orificium of the urethra before voiding. The urine containers were packed as a urine-collection kit. First, they were washed with Deconex 22, which includes a chelating agent. They were then rinsed well with water (A1 quality) and dried carefully in a dust-free environment. Finally, the containers were packed in a urine-collection kit. The samples were kept frozen at –30°C over the entire follow-up period until analysis in 1 batch (Kiilunen et al. Citation1987). The samples were analyzed with inductively coupled plasma-sector field mass spectrometry (ICP-SFMS) (ALS Scandinavia AB, Luleå, Sweden). We did not find any statistically significant difference in creatinine concentration between the preoperative urine samples and the 5-year follow-up samples (data not shown), indicating that only insignificant amounts of creatinine were degraded when stored at –30°C. Therefore, metal concentration was normalized to creatinine concentration (Marco et al. Citation2008).

Patch test

Patch testing was performed with Finn Chambers (8 mm; Epitest Ltd Oy, Tuusula, Finland) on Scanpor tape (Norges-plaster A/S; Alpharma, Vennesla, Norway). Patch test substances were from Hermal (Reinbek, Germany) and Chemotechnique (Malmö, Sweden). Hypersensitivity to metals was tested using the following haptens, ferric chloride (2%), aluminum chloride hexahydrate (2%), vanadium (III) chloride (1%), potassium dichromate (0.5%), nickel sulfate 6H2O (5%), manganese chloride (2%), titanium dioxide (10%), zirconium (IV) chloride (1%), molybdenum (V) chloride (2.5%), and cobalt (II) chloride hexahydrate (1%).

Patch tests were applied on the upper back of the patients. The patients removed the patches 48 h after application. 4 days after application, skin reactions were evaluated in the patient’s home, according to guidelines from the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG). Homogeneous redness and infiltration in the entire test area was scored as a 1+ reaction. Homogeneous redness, infiltration, and vesicles in the test area was scored as a 2+ reaction. Homogeneous redness, infiltration, and coalescing vesicles in the test area was scored as a 3+ reaction. 1+, 2+, and 3+ readings were interpreted as positive responses. An irritant response, a doubtful reading, or a negative reading was interpreted as a negative response. The patch test results were photographed and reviewed by a dermatologist.

Lymphocyte transformation assay

Blood was drawn from patients and transported at 4°C overnight (12–14 h) to the laboratory for analysis. A proliferation assay for peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was performed. PBMCs were isolated from patient blood samples by density gradient centrifugation using LymphoprepTM as described by the manufacturer (Nycomed Pharma A/S, Norway). The cells were resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 0.5 IU/L penicillin, 500 mg/L streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 5% (v/v) autologous plasma. For the proliferation assay, 1 × 105 cells/well were plated in 96-well round-bottom microplates from Nunc. They were incubated with various concentrations of NiCl2, CoCl2, or CrCl2 in triplicate. As a control, cells were incubated with various concentrations of anti-CD3 (clone F101.01; own production). They were incubated for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2, and for the last 6 hours, 0.5 mCi 3H-thymidine (Amersham, UK) was added. Next, the cells were harvested to count the incorporated thymidine using a Topcounter (Perkin Elmer). The stimulation index (SI) was calculated from the ratio of mean counts per minute (cpm) between stimulated cultures and control cultures (with culture medium only). The SI was used to compare the lymphocyte proliferative (reactivity) response. Data were excluded if the SI for the positive anti-CD3 controls was < 2.

History of hypersensitivity

Patients answered an allergy-specific questionnaire for assessment of allergies, information on previous exposure to metals, and information on postoperative changes or progression in hypersensitivity symptoms such as hives, eczema, redness, and itching around the hip (Hallab et al. Citation2001, Thyssen et al. Citation2009c).

Statistics

The continuous variables were tested for normality by performing probability plots and Shapiro-Wilk test, and compared using the t-test or ANOVA as appropriate. If they did not pass the normality tests, we used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskall-Wallis test as appropriate. The categorical data were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The 5-year sample size was calculated using the following equation: N = 2(2α + β)2 × SD2/MIREDIF2 (MIREDIF: Minimal Relevant Difference). Based on an estimated clinically important difference in urine cobalt and chromium concentration of 40% and an SD of 70% between the groups (Kiilunen et al. Citation1987, MacDonald et al. Citation2003, Lhotka et al. Citation2003), the pre-study sample size calculation indicated that 20 patients would be required in each group to achieve a power of 80% at the 5% significance level. Due to the risk of dropout, 26 patients were included in each group. Statistical significance was assumed at p-values < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.0.

Results

Demographics and allergy-specific questionnaire

Patient demographics and the clinically most relevant results from the allergy-specific questionnaire were similar in the 2 groups (). In the MOP/COP group, we found 2 patients with either postoperative redness around the hip without signs of infection or postoperative progression of hypersensitivity.

Urine metal analysis

The urine spot samples were analyzed for the clinically most important metals: cobalt, chromium, molybdenum, and nickel ( and ). A statistically significant 10- to 20-fold increase in cobalt and chromium in the urine was observed in the MOM group throughout the entire follow-up. We did not observe any differences between the patients receiving implants with MOP or COP.

Table 2. MOM vs. MOP. Urine metal levels normalized to creatinine concentration

Table 3. MOP vs. COP. Urine metal levels normalized to creatinine concentration

Patch test

There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of metal hypersensitivity between the MOM group and the MOP/COP group, or between the MOP patients and the COP patients ().

Table 4. Hypersensitivity evaluated by patch test. The number of positive patch tests for each hapten in the MOM group and the MOP/COP group

Lymphocyte transformation assay

We did not find any statistically significant difference in cellular reactivity between the MOM group and the MOP/COP group, or between MOP patients and COP patients ().

Table 5. Lymphocyte transformation assay. The number with positive metal reactivity (SI) > 2.0 in each patient group (the MOM group and the MOP/COP group)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the side effects of resurfacing metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties by comparing urine metal ion release and the prevalence of metal allergy (by patch testing and lymphocytic transformation assay) with that in conventional metal-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty. We found a statistically significant 10- to 20-fold increase in cobalt and chromium urine concentration during the entire five-year follow-up in the MOM group relative to the conventional MOP/COP group. Prevalence of metal allergy after implantation was comparable in the 2 groups, but we must emphasize that incident metal allergy was not evaluated.

This study was designed to evaluate metal ion release and development of metal allergy in a clinical trial with 5-year follow-up. 5-year exposure to metal is sufficient time to develop metal allergy from cutaneous and subcutaneous exposure (Thyssen and Menne Citation2010). Little is known about the effect of internally released metal (Hallab et al. Citation2001, Cousen and Gawkrodger Citation2012); however, it is not unprecedented and the first-generation MOM total hip arthroplasties did cause metal allergy and early failure (Thyssen and Menne Citation2010). One study has proven an increase in metal allergy in patients with loose total knee arthroplasties (no implant: 20%; stable TKA: 48%, p = 0.05; loosened TKA 60%, p = 0.001, respectively) (Granchi et al. Citation2008). Registry studies have not pointed in the same direction (Thyssen et al. Citation2009a). Furthermore, this correlation does not answer the question of whether the poorly functioning hip implants lead to hypersensitivity or whether the hypersensitivity leads to poorly functioning loose implants (Elves et al. Citation1975, Hallab et al. Citation2004, Citation2005, Jacobs and Hallab Citation2006, Gallo et al. Citation2012). To underscore how unpredictable and poorly understood metal allergy is with regard to joint arthroplasties, Thienpont and Berger (Citation2013) reported that a patient with known serious chromium, cobalt, and nickel metal allergy by mistake received a chrome and cobalt knee arthroplasty without having any symptoms of hypersensitivity after surgery at all. A recent review article by Jacobs et al. (Citation2009) argued that the prevalence of hypersensitivity mainly depends on the mere presence and functional status of the replacement. Thus, a longitudinal study would provide a more reliable result, but with 5-year revision rates at approximately 5% and the fact that not all revisions are attributable to metal allergy, this demands a large-scale study. Case-control studies would be more feasible to establish an etiological link in the correlations.

Patch testing of our highly selective group offered some interesting findings. First, cobalt allergy was much more frequent (21%) in both groups than observed in the general population (1%). This is likely to be a result of cobalt release resulting in secondary sensitization. Second, other metal allergies were surprisingly frequent, e.g. to iron, molybdenum, manganese, and vanadium. These metals rarely cause metal allergy in the general population, and the high prevalence observed in our study could be explained by either sensitization following implantation and/or irritant reactions to these metals mimicking true allergic reactions. We advise patch testers to consider the clinical relevance of patch test reactions to such metals, and suggest that controls without implantations should be tested simultaneously with the same allergens to avoid too many false-positive reactions possibly resulting in unnecessary implant removal.

We used a test panel with the most likely haptens (high release, high affinity to sensitize) with all alloy components from implants down to less than 1 weight per cent (Table 6, see Supplementary data). A maximum of 10 samples was used to avoid statistical mass significance; a much larger test panel could be considered to evaluate hypersensitivity in a situation with a known clinical problem (Schalock et al. Citation2012).

The ReCap hip resurfacing system from Biomet was compared with a conventional MOP total hip arthroplasty, Mallory Head/Exeter. Metal allergy was evaluated with the “gold standard” patch test, but also with a lymphocyte transformation assay. Finally, patients were evaluated with a clinically well-proven questionnaire standardizing the patient history (Thyssen et al. Citation2009b). Patch test is the only clinically implemented type-4 hypersensitivity test, but lymphocyte transformation assay has been proposed as giving a closer image of the hypersensitivity generated from internal metal exposure from joint arthroplasties (Schalock et al. Citation2012). In order to ensure a high quality of the lymphocyte transformation assay, we evaluated all blood samples by anti-CD3 reactivity, as a positive control. Reactivity (SI) < 2.0 was catagorized as unusable, and 11 MOM and 9 MOP/COP assays were excluded. As our study shows, the technique can unfortunately be difficult due to transportation. Furthermore, much remains be learned about a positive result that is not closely correlated with a patch test.

Recent studies have shown that cobalt ions released from MOM arthroplasties have the potential to activate human toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) of the innate immune system, and activate a proinflammatory response—which can vary between patients due to genetic factors (Corr and O’Neill Citation2009, Konttinen and Pajarinen Citation2013, Potnis et al. Citation2013, Tyson-Capper et al. Citation2013). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that TLR4 activation resulted in false-positive hypersensitivity (type 4) to cobalt in the MOM group. However, this does not explain the cobalt hypersensitivity in the MOP/COP group.

Our study had some other limitations. First, the MOM group lost 7 patients to final follow-up, as compared to 1 patient in the MOP group. 1 was reoperated due to fracture of the femoral neck, 3 did not reply to invitation, and 3 did not want to participate. The large difference between the 2 groups introduced selection bias, but the groups were still comparable at 5 years regarding gender and other markers of hypersensitivity ().

In summary, we observed increased metal ion release during the entire follow-up period. We did not find any proof or tendency of more metal allergy in the MOM group, all of whom had well-functioning implants. The impact of long-term metal exposure remains uncertain.

Supplementary data

Table 6 is available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 6484.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (29.9 KB)KG: hypothesis, collection of data, data analysis, and writing of first draft. SSJ: hypothesis, study design, collection of data, data analysis, statistical analysis, and critical review of manuscript. NDL: hypothesis, collection of data, data analysis, and critical review of manuscript. JPT and CMB: hypothesis, data analysis, and critical review of manuscript. MS: hypothesis, collection of data, data analysis, and critical review manuscript. TBH and KS: hypothesis, study design, collection of data, data analysis, and critical review manuscript.

We thank Flemming Møller Larsen MD and Thomas Prynø MD for performance of the hip surgery.

No competing interests declared.

- Baad-Hansen T, Storgaard Jakobsen S, Soballe K. Two-year migration results of the ReCap hip resurfacing system-a radiostereometric follow-up study of 23 hips. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (4): 497-502.

- Benson MK, Goodwin PG, Brostoff J. Metal sensitivity in patients with joint replacement arthroplasties. Br Med J 1975; 4 (5993): 374-5.

- Chan FW, Bobyn JD, Medley JB, Krygier JJ, Tanzer M. The otto aufranc award. wear and lubrication of metal-on-metal hip implants. Clin Orthop 1999; (369): 10-24.

- Coleman RF, Herrington J, Scales JT. Concentration of wear products in hair, blood, and urine after total hip replacement. Br Med J 1973; 1 (5852): 527-9.

- Corr SC, O’Neill LA. Genetic variation in toll-like receptor signalling and the risk of inflammatory and immune diseases. J Innate Immun 2009; 1 (4): 350-7.

- Cousen PJ, Gawkrodger DJ. Metal allergy and second-generation metal-on-metal arthroplasties. Contact Dermatitis 2012; 66 (2): 55-62.

- Doorn PF, Campbell PA, Worrall J, Benya PD, McKellop HA, Amstutz HC. Metal wear particle characterization from metal on metal total hip replacements: Transmission electron microscopy study of periprosthetic tissues and isolated particles. J Biomed Mater Res 1998; 42 (1): 103-11.

- Elves MW, Wilson JN, Scales JT, Kemp HB. Incidence of metal sensitivity in patients with total joint replacements. Br Med J 1975; 4 (5993): 376-8.

- Firkins PJ, Tipper JL, Saadatzadeh MR, Ingham E, Stone MH, Farrar R, Fisher J. Quantitative analysis of wear and wear debris from metal-on-metal hip prostheses tested in a physiological hip joint simulator. Biomed Mater Eng 2001; 11 (2): 143-57.

- Gallo J, Konttinen Y, Goodman S, Thyssen J, Gibon E, Pajarinen J, Takakubo Y, Schalock P, Mackiewicz Z, Jämsen E, Petrek M, Trebse R, Coer A, Takagi M. Aseptic loosening of total hip arthroplasty as a result of local failure of tissue homeostasis, recent advances in arthroplasty, dr. samo fokter (ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-990-5, InTech, available from: Http://Www.intechopen.com/books/recent-advances-in-arthroplasty/aseptic-loosening-of-total- hip-arthroplasty-as-a-result-of-local-failure-of-tissue-homeostasis 2012: 319-63.

- Gawkrodger DJ. Metal sensitivities and orthopaedic implants revisited: The potential for metal allergy with the new metal-on-metal joint prostheses. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148 (6): 1089-93.

- Granchi D, Cenni E, Tigani D, Trisolino G, Baldini N, Giunti A. Sensitivity to implant materials in patients with total knee arthroplasties. Biomaterials 2008; 29 (10): 1494-500.

- Grigoris P, Roberts P, Panousis K, Jin Z. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: The evolution of contemporary designs. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 2006; 220 (2): 95-105.

- Hallab NJ, Merritt K, Jacobs JJ. Metal sensitivity in patients with orthopaedic implants. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83 (3): 428-36.

- Hallab NJ, Anderson S, Caicedo M, Skipor A, Campbell P, Jacobs JJ. Immune responses correlate with serum-metal in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty (Suppl 3) 2004; 19 (8): 88-93.

- Hallab NJ, Anderson S, Stafford T, Glant T, Jacobs JJ. Lymphocyte responses in patients with total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 2005; 23 (2): 384-91.

- Jacobs JJ, Hallab NJ. Loosening and osteolysis associated with metal-on-metal bearings: A local effect of metal hypersensitivity? J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (6): 1171-2.

- Jacobs JJ, Urban RM, Hallab NJ, Skipor AK, Fischer A, Wimmer MA. Metal-on-metal bearing surfaces. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009; 17 (2): 69-76.

- Kiilunen M, Jarvisalo J, Makitie O, Aitio A. Analysis, storage stability and reference values for urinary chromium and nickel. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1987; 59 (1): 43-50.

- Konttinen YT, Pajarinen J. Adverse reactions to metal-on-metal implants. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013; 9 (1): 5-6.

- Lhotka C, Szekeres T, Steffan I, Zhuber K, Zweymuller K. Four-year study of cobalt and chromium blood levels in patients managed with two different metal-on-metal total hip replacements. J Orthop Res 2003; 21 (2): 189-95.

- MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW, Chess DG, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Cleland D, Leung F. Metal-on-metal versus polyethylene in hip arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Orthop 2003; (406): 282-96.

- Marco R, Katorza E, Gonen R, German U, Tshuva A, Pelled O, Paz-Tal O, Adout A, Karpas Z. Normalisation of spot urine samples to 24-h collection for assessment of exposure to uranium. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2008; 130 (2): 213-23.

- Marshall A, Ries MD, Paprosky W, Implant Wear Symposium 2007 Clinical Work Group. How prevalent are implant wear and osteolysis, and how has the scope of osteolysis changed since 2000? J Am Acad Orthop Surg (Suppl 1) 2008; 16: S1-6.

- Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (7): 847-51.

- Petersen MK, Andersen NT, Mogensen P, Voight M, Soballe K. Gait analysis after total hip replacement with hip resurfacing implant or mallory-head exeter prosthesis: A randomised controlled trial. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (5): 667-74.

- Potnis PA, Dutta DK, Wood SC. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway mediates proinflammatory immune response to cobalt-alloy particles. Cell Immunol 2013; 282 (1): 53-65.

- Rieker C, Kottig P. In vivo tribological performance of 231 metal-on-metal hip articulations. HIP Int 2002; 12: 73-6.

- Schalock PC, Menne T, Johansen JD, Taylor JS, Maibach HI, Liden C, Bruze M, Thyssen JP. Hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants–diagnostic algorithm and suggested patch test series for clinical use. Contact Dermatitis 2012; 66 (1): 4-19.

- Scifert CF, Brown TD, Pedersen DR, Callaghan JJ. A finite element analysis of factors influencing total hip dislocation. Clin Orthop 1998; (355): 152-62.

- Shimmin A, Beaule PE, Campbell P. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008; 90 (3): 637-54.

- Sieber HP, Rieker CB, Kottig P. Analysis of 118 second-generation metal-on-metal retrieved hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (1): 46-50.

- Thienpont E, Berger Y. No allergic reaction after TKA in a chrome-cobalt-nickel-sensitive patient: Case report and review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21 (3): 636-40.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T. Metal allergy--a review on exposures, penetration, genetics, prevalence, and clinical implications. Chem Res Toxicol 2010; 23 (2): 309-18.

- Thyssen JP, Jakobsen SS, Engkilde K, Johansen JD, Soballe K, Menne T. The association between metal allergy, total hip arthroplasty, and revision. Acta Orthop 2009a; 80 (6): 646-52.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Menne T, Nielsen NH, Linneberg A. Nickel allergy in danish women before and after nickel regulation. N Engl J Med 2009b; 360 (21): 2259-60.

- Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menne T, Nielsen NH, Johansen JD. The association between hand eczema and nickel allergy has weakened among young women in the general population following the danish nickel regulation: Results from two cross-sectional studies. Contact Dermatitis 2009c; 61 (6): 342-8.

- Tyson-Capper AJ, Lawrence H, Holland JP, Deehan DJ, Kirby JA. Metal-on-metal hips: Cobalt can induce an endotoxin-like response. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72 (3): 460-1.