Abstract

The United Nations projects that the number of individuals with dementia in developed countries alone will be approximately 36,7 million by the year 2050. International recognition of the significant emotional and economic burden of Alzheimer's disease has been matched by a dramatic increase in the development of pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to this illness in the past decade. Changing demographics have underscored the necessity to develop similar approaches for the remediation of the cognitive impairment associated with more benign syndromes, such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and age-associated cognitive decline (AACD). The present article aims to provide an overview of the most current therapeutic approaches to age-associated neurocognitive disorders. Additionally, it discusses the conceptual and methodological issues that surround the design, implementation, and interpretation of such approaches.

Las Naciones Unidas proyectan que el número de individuos con demencia sólo en los países desarrollados será de aproximadamente 36,7 milIones para el año 2050. El reconocimiento internacional del significado emocional y de la carga económica de la enfermedad de Alzheimer se ha acompañado de un incremento dramático en el desarrollo de propuestas farmacológicas y no farmacológicas para esta enfermedad en la última década. Los cambios demográficos han subrayado la necesidad de desarrollar estrategias similares para remediar el deterioro cognitivo asociado con síndromes más benignos, tales como el deterioro cognitivo leve (DCL) y la declinación cognitiva asociada con la edad (DCAE). El presente articulo apunta a proveer una visión acerca de las propuestas terapéuticas más actuales para los trastornos neurocognitivos asociados con la edad. Adicionalmente se discuten temas concepiuales y metodológicos que se relacionan con el diseño, implementatión e interpretatión de tales propuestas.

Les Nations unies estiment que le nombre de personnes atteintes de démence sera de l'ordre de 36,7 millions en 2050 en ce qui concerne les seuls pays développés. La prise de conscience internationale de la charge économique et affective considérable que représente la maladie d'Alzheimer s'est accompaqnée d'une auqmentation spectaculaire du développement des recherches pharmacologiques et non pharmacologiques de cette maladie dans les dix dernières années. L'évolution des données démographiques a mis en évidence la nécessité de développer des approches similaires pour remédier au déficit cognitif associé à des syndromes moins graves, tels que le déficit cognitif bénin (MCI) et le déclin cognitif lié à l'âge (AACD). Cet article a pour but de fournir une vue d'ensemble des approches thérapeutiques les plus courantes ayant trait aux troubles neurocognitifs liés à l'âge. En outre, il examine les problèmes méthodologiques et conceptuels soulevés par la conception, la réalisation, et l'interprétation de telles approches.

There is an extensive range of neurocognitive disorders that are particularly prominent in older adults. These include neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), frontal lobe dementia, Lewy-body dementia, Parkinson's disease; cerebrovascular disorders such as vascular dementia; and more benign syndromes such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and age-associated cognitive decline (AACD). In recent years, there has been a burgeoning of research on therapeutic approaches to these disorders. Changing demographics have underscored the necessity to develop interventions for the remediation of the cognitive impairment associated with pathological and normal aging.

The prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia rises exponentially with increasing age. According to recent United Nations projections, between the years 2000 and 2050 the number of individuals over 65 years of age will exceed 1.1 billion worldwide. Based on these figures, the United Nations projects that the number of individuals with dementia in developed countries alone will increase from 13.5 million to 36.7 million.Citation1 Utilizing these demographics as well as current cost of care figures, Katz man and FoxCitation2 estimate that by 2050 the annual economic toll of dementia will be $383.1 billion in the USA, $124.6 billion in Italy, $30.5 billion in France, and $11.2 billion in England. The burden of this illness is such that investigators stress not only the importance of finding a cure, but also the necessity of intervening in the early stages of dementia to prolong functionality and extend the time before institutionalization.

These changing demographics will also impact the prevalence and incidence of MCI and AACD, since as many as 50% of individuals over age 65 currently fulfill the criteria for at least one of these conditions. Such impairments in cognition influence many day-to-day activities, from medication adherence to productivity in the workplace and at home.Citation3 Additionally, extended longevity rates and increasing numbers of older adults in our society suggest that older workers may be required to continue working to prevent financial overload on the retirement and pension systems. Citation4,Citation5 The elimination of mandatory retirement for most occupations in the USA has made it possible for older adults to stay in the workplace. Maintaining memory and cognitive function is obviously important for older adults, who want to - or are obliged to - continue working. The end result of these social changes is that older adults may not only want to live longer with better cognitive function, they may also need to. Additionally, preserving cognitive function helps maintain aspects of living, such as personal independence, that contribute to the good health and overall quality of life in older adults.

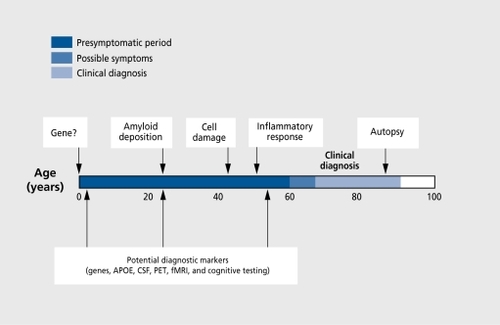

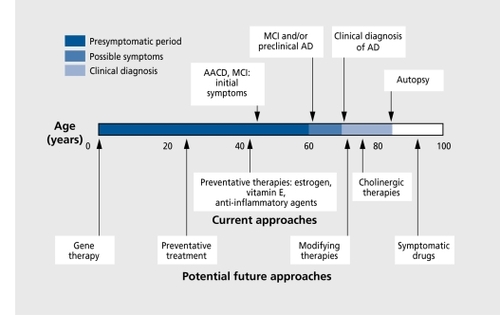

In this article, we provide an overview of the current pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to the cognitive impairments associated with AD, MCI, and AACD, since these represent the most prevalent neurocognitive syndromes among older adults. Additionally, the neuropathological mechanisms hypothesized to underlie AD may also contribute to MCI and AACD. Indeed, many investigators suggest there is a spectrum of pathophysiological changes that accompany the normal aging process, increase in severity to produce AACD and MCI, and, in their most severe form, result in dementia. Such pathologies include neurotransmitter deficiencies (particularly cholinergic deficits), β-amyloid deposits, inflammation, neuroendocrine abnormalities, and immunological impairment. Additionally, the genetic and environmental risk factors for the development of dementia also appear to be associated with MCI and AACD.Citation6,Citation7 Thus, the therapeutic approaches developed to intervene with dementia have informed, and will continue to inform, similar approaches to MCI and AACD ( and ).Citation8

Alzheimer's disease

AD is the most common form of dementia accounting for 50% to 70% of all cases (Table I). Currently, there are an estimated 4 million individuals with dementia in the USA with more than 100 000 deaths annually, with France, Italy, and England having close to 1 million cases each,2 and in Greece there are 200 000 cases.9 AD is a progressive, neurodegenerative disorder, characterized ncuropathologically by widespread neuronal loss, presence of neurofibrillary tangles, and deposits of β-amyloid in cerebral blood vessels and neuritic plaques. Since the medial-temporal lobes, hippocampus, and association cortex arc significantly impacted, it is not surprising that the primary symptom of AD is a decline in cognitive functioning, which leads to marked impairment in daily functioning. In particular, memory impairments, visuospatial decline, language difficulties, and loss of executive function are central cognitive symptoms of this illness. Behavioral disturbances such as agitation and hallucinations often accompany disease progression. However, as emphasized by Cummings,10 despite the presence of core clinical features, there is significant heterogeneity in the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD.

Table I. Prevalence of dementia.

The illness lasts approximately 7 to 10 years, with patients requiring total care in the latter stages. Thus, AD places a tremendous emotional and economic burden on both patients and their caregivers. Beyond a cure, therapeutic approaches that would alleviate the symptoms or delay progression could be of substantial benefit. When they modeled the public health impact of delaying AD onset in the USA, Brookmeyer and associates found that delaying onset by as little as 6 months could reduce the numbers of AD patients by half a million by 2050.Citation8,Citation11 However, despite significant progress in our characterization and understanding of AD, to date there is no cure and researchers are still trying to more fully understand its etiology. The pathophysiology of the illness is complex and, as many investigators suggest, likely involves multiple, overlapping, and potentially interactive pathways to neuronal damage.Citation10,Citation12 However, in the past decade there has been a significant increase in the development of pharmacological approaches to this illness.

Current pharmacological approaches to Alzheimer's disease

Neurobiological features of AD, including accumulation of β-amyloid, neurotransmitter deficiencies, oxidation, and hypothesized impairments in inflammatory and neuroendocrine mechanisms have informed the development of current pharmacologic approaches. Table II lists the central pathophysiological mechanisms hypothesized to lead to AD and their associated pharmacological therapies.

Table II. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease and associated therapeutic approaches. HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A.

Neurotransmitter deficiencies

Cholinergic deficits. To date, the best-developed treatment for the symptoms of AD has been the attempt to remediate the cholinergic deficit observed in this illness. On autopsy cholinergic markers in the cerebral cortex of AD patients are reduced and these decreases correlate with cortical pathology.Citation13,Citation14 AD patients have been shown to have substantial neocortical deficits in choline acetyltransferase (CAT), the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of acetylcholine (ACh),Citation15-Citation17 reduced choline uptake and ACh release,Citation18,Citation19 and degeneration of cholinergic neurons of the nucleus basalis of Meynert.Citation20 Other investigations have also observed a significant reduction in the number of muscarinic and nicotinic ACh receptors in AD brains.Citation21,Citation22

Cholinergic deficits are well documented to be correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment in AD patients, and the neurotransmitter ACh has long been implicated in learning and memory processes.Citation14,Citation21 This has led to the ”cholinergic hypothesis“ of AD, which holds that degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and the associated loss of cholinergic neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex and other areas contribute significantly to the deterioration in cognitive function seen in patients with AD.

The most successful approach to remediate the cholinergic deficit in AD has been the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs). AChEIs inhibit the enzyme, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which metabolizes ACh. Inhibiting the action of the enzyme increases the concentration and duration of action of ACh in synapses. AChEIs are currently the most successful drugs for enhancing ACh transmission and appear more physiologically beneficial than direct cholinoceptor activation. Three AChEIs, tacrine, donepczil, and rivastigminc, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are currently available on the market in over 60 countries. Galant-amine has been approved in Europe and has been submitted for approval by the FDA.

To assess the impact of pharmacological agents on cognition and severity of illness, most clinical trials of AD utilize the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog), the Mini -Mental State Examination (MMSE), and some assessment of clinical impression of change, such as the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change (CIBIC) scale. The ADAS-Cog is a psychometric scale that evaluates aspects of orientation, attention, memory, language, reasoning, and praxis.Citation23,Citation24 The MMSE is a brief mental status examination designed to quantify global cognitive status by assessing orientation, language, calculation, memory, and visuospatial reproduction.Citation25 While we stress that there is significant heterogeneity, studies suggest. that the average rate of decline is 2 to 4 MMSE points per annum, while the ADAS-Cog scores may increase on average by 3 to 10 points per year, depending upon the severity of the illness.Citation26-Citation28

Tacrine was the first AChEI to receive FDA approval for use in AD patients in 1993, but its use resulted in only modest improvements in cognition.Citation29-Citation31 In addition, tacrine has a lower bioavailability (amount of drug available in the body after absorption) than second-generation cholinestera.se inhibitors, such as donepezil hydrochloride.Citation32 It has also a poor side-effect profile that includes ttepatotoxicity. Currently 40% of AD patients in the USA are estimated to be taking donepezil, which received FDA approval in 1996.Citation33 Donepezil is a highly selective, noncompetitive, reversible AChEl.Citation34 It has a good side-effect profile, which is not associated with hepatotoxicity, and substantially more patients are able to tolerate and achieve therapeutic levels of donepezil than of tacrine.Citation35 Also, there is greater case of administration with donepezil. Uric elimination half-life is considerably longer for donepezil (70 to 80 h) in comparison to most other AChEIs (0.3 to 12 h).

A statistically significant improvement in cognition has been observed in most randomized clinical trials of donepezil, with an average improvement relative to placebo of 2 and 3 points on the ADAS-Cog for 5 and 10 mg/day doses, respectively.Citation34,Citation36,Citation37 However, this represents a relatively modest improvement in cognition and the impact of this degree of improvement on function is unclear. Indeed, some donepezil trials did not find that patients perceived any substantive improvement in function, despite objective improvement in cognition and clinical impression scales. Yet, a preliminary study utilizing pupil reaction to light found that AD patients taking donepezil exhibited longer latencies and higher amplitude of maximal response to light than controls.Citation38

Rivastigmine is a selective, reversible inhibitor of both AChE and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE).Citation39,Citation40 Doubleblind, placebo-controlled clinical trials lasting 6 months found that rivastigmine resulted in statistically significant differences in cognition in patients with mild-to-moderate AD.Citation41 In particular, use of higher doses for 26 weeks resulted in the most efficacious impact of rivastigmine on cognition, with improvement of an average of 3 to 4 points on the ADAS-Cog relative to placebo.Citation42,Citation43 It appears that rivastigmine requires a longer titration period to reach therapeutic doses than donepezil.Citation44 However, Farlow et alCitation43 observed that patients originally treated with 6 to 12 mg/day dose of rivastigmine for 52 weeks had only a 1.5-point improvement on the ADAS-Cog relative to the placebo group.

Additional AChEIs arc in submission for approval in the USA, including the second-generation galantamine, which modulates nicotinic cholinergic activity, and metrifonate. Findings from phase 2 and phase 3 randomized clinical trials of galantamine observe an average of a 1.5-point improvement on the ADAS-Cog relative to baseline in the drug group, and an improvement of an average of 3 points relative to placebo.Citation45-Citation48 The development of other AChEIs, such as phenserinc, a derivative of the first-generation physostigmine, is in progress.

Overall the AChEIs have produced only modest improvements in the cognitive symptoms of AD patients, often resulting more in stabilization than alleviation of cognitive symptoms. Yet as data from clinical trials cumulate, it appears that such stabilization may persist for up to 1 year in a significant number of patients and longer-term, studies suggest that the progression of the disease is slowed by the use of AChEIs.Citation34,Citation49 This may, in part, reflect the observation that ACh stimulation appears to reduce the production of β-amyloid through its action on the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Moreover, long-term use of tacrine has been associated with preservation of nicotinic receptor binding as measured by positron emission tomography (PET).Citation50 In addition to the potential physiological benefits of long-term use of AChEIs, pharmoeconomic analyses suggest that there maybe significant cost-savings if AChEI use prevents AD decline for even 6 months.Citation51-Citation53 Thus, the refinement and development of cholinestera.se inhibitors continues, even though AChEIs do not reverse or retard the neurodegeneration, which is the hallmark of this illness.

There are pharmacologic approaches to the cholinergic deficiency, other than inhibition of AChE. For example, muscarinic agonists to enhance the effect of ACh on nerve cell receptors are in development. Since AChEIs depend upon intact cholinergic neurons, direct-acting receptor agonists that act at postsynaptic cholinergic sites have the advantage of bypassing possibly degenerated presynaptic terminals to enhance neuronal activity.

Other neurotransmitter deficiencies. AD-related depletions in other neurotransmitters are also being considered for therapeutic approaches. Glutamatergic deficits have been observed, with evidence indicating the loss of glutamate markers in the brains of AD patients, particularly in corticocortical connections.Citation54,Citation55 Additionally, the glutamate receptor, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA),has long been implicated in the acquisition of new memories and has thus become a target for improving memory function in AD. Memantinc, an uncompetitive NMDA antagonist has been employed in European countries for the treatment of dementia. However, while it appears to have a positive impact on the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Change (CGI-C) and measures of function, its impact on cognition is less clear.Citation56 In general, the development of glutamate agonists has been hampered by the potential neurotoxic effects of overstimulating this system.Citation57 UTius, investigators have attempted indirect activation using glycine-like agonists, such as milacemide. Several large, clinical trials of milacemide in AD patients found no therapeutic benefit on the ADAS, MMSE, or CGI-C.Citation58,Citation59

Ampakines are also in development and aim to increase activity of the glutamate receptor, α-amino-3-hydroxy5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA). While the ampakinc Ampalex® (1-[quinoxalin-6-ylcarbonyl]piperidine, CX516) has been found to improve short-term memory function in normal elderly adults,Citation60 there are as yet no data on its use in AD patients. Another compound, S12024 has been suggested to facilitate noradrenergic systems.Citation61,Citation62 Initial clinical trials with this agent find improvement on the MMSE in AD patients relative to placebo, over a 12-week period.Citation63

AD-related deficiencies have also been observed in serotonin and norepinephrine, but, although deficiencies in these neurotransmitters are associated with cognitive impairment, their enhancement is being considered primarily to treat the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms that can accompany AD.

β-Amyloid deposition

Many believe that more directly targeting the pathogenic mechanisms involved in AD might result in more efficacious treatments. A central neuropathological feature of AD is the accumulation of extracellular plaques, which contain the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ). In addition to direct neurotoxic effects, Aβ appears to activate microglia producing neurotoxins, cytokines, and free radicals.Citation64,Citation65 Several studies report that Aβ may compromise cholinergic neuronal function independently of neurotoxicity suggesting an association between Aβ deposits and cholinergic dysfunction in AD.Citation66,Citation67 Animal studies have found infusion with Aβ to be associated with impairments in spatial and working memory deficits:Citation68 Recently, there has been increased focus on preventing the formation of Aβ, and the amyloid cascade hypothesis offers a number of potential therapeutic targets. In particular, a central approach has been the inhibition of the β- and γ-secretases that produce Aβ from the APP. As emphasized by Citron,Citation69 there is no evidence for additional functions for Aβ; however, β- and γ-sccretases are present in many different cells of the body and potentially have substrates in addition to APR Thus, their inhibition may have associated toxicity effects. There are also concerns that, by the time of diagnosis, when the amyloid burden is sufficiently high in AD patients, secretase inhibitors may only minimally impact the existing symptoms. Clearance of existing plaques also would be required for effective treatment. While inhibition of the β- and β-sccretascs may represent a particularly effective approach to this disease, such treatments are still in development.

A novel approach utilizing an immunological model, observed amelioration of β-amyloid deposits in a mouse model of AD following treatment with a vaccine combining amyloid and substances that excite the immune system.Citation70 The reduction in Aβ was observed not only in younger mice, where vaccine treatment preceded onset, but, also in older animals where Aβ deposits were already present. Phase 1 trials investigating this approach in AD patients are currently nearing completion in the USA and Europe.

Inflammation

AD lesions are also characterized by the presence of inflammatory proteins. These include acute phase reactants, inflammatory cytokines, and components of the complement cascade.Citation71 The inflammatory proteins observed in AD are produced by microglia and/or astrocytes. The parallel observation of an inverse relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and AD led to the hypothesis that anti-inflammatory agents reduce AD risk. Recent literature suggests an association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use and decreased AD risk, including prospective data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. This has led to the initiation of several clinical trials of anti-inflammatory agents, many of which are still ongoing.

As early as 1993, it, was noted that patients with mild-tomoderate AD treated with indomethacin, exhibited stable cognitive performance relative to patients on placcbo.Citation72 However, not all clinical trials with anti-inflammatory agents have yielded positive findings. 'The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (from the National Institute of Aging [NIA]),Citation73 a multicentcr, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose steroid prednisone conducted in a total of 138 subjects, observed no difference in cognitive decline (assessed by the ADAS-Cog) between the prednisone and placebo treatment groups in the primary intentto-treat, analysis, or in a secondary analysis which included completers only. On the basis of these findings, they concluded that prednisone did not seem to be therapeutic for AD patients.

Clinical trials of new anti-inflammatory agents, such as the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX II), inhibitors are ongoing. Several investigators have suggested that COX II inhibition directly impacts neuronal function in addition to inflammatory microglia since COX II is present not only in microglia but also in neurons.Citation74,Citation75 Moreover, on the basis of animal and cell studies, investigators suggest that COX II activity may contribute to neurodegencration in AD by oxidative mechanisms.Citation76 Additional anti-inflammatory drugs, including hydroxychloroquine and colchicine, are being examined in clinical trials with AD patients.

Oxidation

Excess brain protein oxidation and decreased endogenous antioxidant activity are well noted in both normal aging and AD.Citation77 Thus, reduction of oxidative stress has become a target, for the treatment of AD. Agents that protect against oxidative damage, such as vitamin E and Ginkgo biloba extract, are thought, to reduce neuronal damage and potentially slow the onset and/or progression of AD. An extensive clinical trial of vitamin F, and selegiline, a type B or selective monoamine oxidase inhibitor, in AD patients found that both compounds delayed the progression of nursing home placement by approximately 6 months, thus precipitating the widespread use of vitamin E. However, data on the effects of such compounds on cognitive symptoms is more limited. While preliminary studies indicate that both agents are associated with improvements in cognition in AD patients and asymptomatic older adults, lack of statistical power limits generalization from these findings.Citation71

G biloba has also been employed in clinical trials with AD. While the therapeutic activity of G biloba is complex and likely involves the interaction and modulation of several biological systems, evidence suggests that it is an effective scavenger of both primary and secondary free radicals.Citation78,Citation79 Findings from short-term clinical trials, which indicated that G biloba might, be effective in AD patients,Citation80-Citation82 have been supported by larger, longer-term investigations. At 52 weeks, patients receiving G biloba performed significantly better than the placebo group on the ADAS-Cog, although no differences were observed with respect to the CGI-C. Additionally, 26% of the patients achieved at least a 4-point improvement on the ADAS-Cog, compared to 17% with placebo (P =0.04) ,Citation83

Estrogen appears to act as both an antioxidant, protecting brain cells from, toxins by trapping free radicals, and an anti-inflammatory agent by inhibiting brain cell deterioration.Citation84 Estrogen also is known to increase the level of CAT in the basal forebrain, the frontal cortex, and most, importantly in the CA1 layer of the hippocampus. Additionally, many investigations suggest that estrogen plays a role in promoting the growth and/or survival of neurons in areas analogous to those most, sensitive to degeneration in AD, and animal studies indicate that estrogen maintains dendritic spine density in Mppocampal pyramidal cells, regulates receptors in the hippocampus, and stimulates synapse formation.Citation84-Citation86

Recent epidemiological studies suggest that, estrogen use in women may significantly delay AD onset and lower AD risk. In a prospective case-control study, Kawas et alCitation87 utilized records of 472 post- and perimenopausal women who were followed for up to 16 years. Women taking estrogen had a 54% reduction in risk for AD compared with women who did not. Similarly, TangCitation88 found that estrogen use during menopause significantly delayed AD onset and lowered AD risk. There is also a significant literature documenting a positive effect of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) on the memory and cognition of nondemented individuals. However, despite these findings, recognition of the nonrandom basis by which estrogen is elected in the general population requires that epidemiological evidence be supported by well-controlled randomized clinical trials.

To date, only a limited number of randomized clinical trials of estrogen have been conducted in AD patients and these have yielded mixed results. While some have found that estrogen improved cognition in AD patients,Citation89 others did not. In particular, two recent clinical trials found no benefit of estrogen on cognitive function patients with mild-tomoderate AD. Although one of these was only 16 weeks in duration,Citation90 the year-long, multisite Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study found that FRT did not slow disease progression and no differences between the treatment and placebo group were observed with respect to cognitive or functional measures.Citation91 Shaywitz and SbaywitzCitation92 suggest that, in line with findings from animal studies, estrogen may be most effective during initial use. For example, Mulnard et alCitation91 found that estrogen-treated AD patients exhibited significantly higher scores on the MMSE relative to placebo after 8 weeks, although no difference between the groups was observed after 1 year of treatment. While there are not yet sufficient data to reach a definitive conclusion regarding the merits of ERT for improving or stabilizing the cognitive symptoms of AD patients, estrogen may be effective in preventing or delaying the onset, of dementia.

Neuronal degeneration

Neuronal degeneration is a central feature of AD, with cell loss occurring throughout the brain, but most, dramatically in association cortex, medial temporal lobes, and hippocampus. Thus, neurotrophic factors that might, preserve and stimulate neuronal development have received increasing interest. Several investigators suggest that nerve growth factor (NGF) might be valuable for the treatment of AD, but, its inability to cross the blood-brain barrier has posed difficulties for this approach.Citation93 Research has focused on the use of agents that appear to stimulate NGF production in the brain, such as idebenone. One of the first double-blind, multisite clinical trials to employ this agent in AD patients found that patients treated with idebenone for 12 months exhibited statistically significant, dose-dependent improvement, on the ADAS-Cog and its noncognitive counterpart subscale, ADAS-Noncog, as well as on the CGI-C and instrumental, activities of daily living (IADL) subscales.Citation94 Further studies arc required before the efficacy of idebenone can be fully assessed.

Nootropics are suggested to be neural stimulants that appear to augment neuronal function, including neurotransmitter release. However, clinical trials with two common nootropics, piracetam and pramiracetam have yielded mixed results in AD patients.Citation95-Citation97 As Flicker and GrimleyEvansCitation98 conclude, the available evidence does not support the use of piracetam. in the treatment of people with dementia because effects were found predominantly on global impression of change, but not on any of the more specific measures.

Recently, there has been increased focus on Ccrebrolysin®, a porcine brain-derived peptide preparation, which has been suggested to have neurotropic activity.Citation99 'The results of in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that Cerebrolysin® may reduce microglial, activation, thus reducing the extent of inflammation and accelerated neuronal death.Citation100 Two recent placebo-controlled clinical trials found that, over a 4-week period, Cerebrolysin®-treated AD patients exhibited significant improvement on the ADAS-Cog, CGI-C, and the MMSE.Citation101,Citation102 Additionally, Ruther et alCitation102 found that the improvements in cognition observed at 4 weeks appeared to sustain in the drug group for up to 6 months posttreat ment. However, the long-term efficacy of this agent still needs to be evaluated.

Neuroendocrine impairment

Impairment, in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity is another physiological mechanism proposed to underlie the development of AD.Citation103-Citation106 Hypercortisolemia and reduced negative feedback inhibition of Cortisol secretion are noted concomitants of AD.Citation107-Citation110 However, investigations of the relationship between dementia severity and Cortisol levels have yielded mixed findings. While some investigations observe a relationship between dementia severity and/or progression,Citation111-Citation115 others do not observe this relationship between HPA dysfunction and either severity or disease progression in AD.Citation116-Citation118

However, variations in age of onset and stage of illness may impact the relationship between hypercortisolemia and disease progression. Moreover, the nature of the relationship between Cortisol and cognitive decline in AD may be more difficult to assess as the disease progresses. As many suggest, the degenerative process of hippocampa! damage in AD patients may, with time, reduce the responsivity of this area to elevations in glucocorticoids. Thus, many investigators argue that impairments in neuro-endocrine function observed in AD reflect, rather than cause the neuronal degeneration in this illness. However, the observations of a negative impact of elevated Cortisol levels on cognition in normal aging have led others to consider therapeutic approaches to AD based upon this pathophysiological mechanism. Currently, a clinical trial of AD patients, utilizing the glucocorticoid antagonist, mifepristone, is in progress.

Cerebrovascular and cardiovascular impairments

While cerebrovascular deficiencies arc typically associated with vascular dementia, an increasing body of evidence suggests that vascular factors may also contribute to the development, of AD.Citation119 Many recent studies have found arterial hypertension to be associated with cognitive impairmentCitation120-Citation123 and increased risk of AD has also been observed in individuals with higher systolic-diastolic blood pressure values.Citation124 Hofman et alCitation125 observed patients with AD to be affected by more pronounced arteriosclerotic carotid lesions, and atrial fibrillation was found to be more strongly associated with AD (with cerebrovascular disease) than with vascular dementia.

Some investigators have argued that vascular factors such as arterial hypertension may have a direct role in the pathogenesis of AD by increasing the production of β-amyloid. Animal studies have found ischemia to result in increased β-amyloid production in the hippocampus.Citation126 Moreover, the observation of increased concentrations of senile plaques in the brains of hypertensive, nondemented patients further implicates the role of ischemia.Citation127 Investigators have started to consider the use of antihypertensive agents as a potential. therapeutic approach to AD, but a recent study of such agents in hypertensive, nondemented older adults indicated a minimal positive impact, upon cognitive impairment, after 3 and 12 months of treatment.Citation128 However, the Syst-Eur study found that, use of a calcium-channel-blocking agent reduced the incidence of AD in older adults with isolated systolic hypertension.Citation129

In addition to the hypothesized association between hypertension and the development, of AD, the past few years have seen a dramatic increase in the literature on the potential link between cholesterol levels and the development of AD. Several animal studies have found hypercholesterolemia to accelerate AD amyloid pathology,Citation130,Citation131 and cholesterol was observed to modulate the membrane disordering effects of β-amyloid in the hippocampi of AD patients.Citation132 The apolipoprotcin E (APOE) susceptibility gene for AD encodes for the APOE protein, which, among other things, is implicated in the transport of plasma cholesterol. Recent studies have also found increased scrum cholesterol levels to be associated with presence of the ε4 allele in AD patients.Citation133-Citation137 Some studies did not observe this association,Citation138 and still others suggest, that the ε4 allele is independently associated with hypercholesterolemia and development of AD.Citation139

Overall, however, these findings have led investigators to hypothesize a relationship among heart disease, cholesterol levels, and the development, of AD.Citation119,Citation131 Wolozin et alCitation140 recently reported a decrease in the prevalence of AD to be associated with the use of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, and a placebo-controlled clinical trial of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, Lipitor® (atorvastatin calcium) is currently ongoing in patients with mild-to-moderate AD.

It is interesting to note that estrogen has a positive impact, on lipoprotein levels and enhances cerebral blood flow, and several investigators have proposed that these physiological. benefits of estrogen may account for its association with reduced AD risk. Similarly, G biloba is noted to protect, against ischemic damage, and may thus have benefits on cognition in AD patients.

Methodological and conceptual issues regarding therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer's disease

While this is an exciting time for the development of pharmacological approaches to AD, overall, the results of initial randomized clinical trials of agents such as estrogen and anti-inflammatory drugs have been somewhat disappointing. There are several important, conceptual and methodological issues that significantly impact the interpretations we can draw from the findings of many clinical trials in AD. First, given the complexities of the pathophysiological mechanisms that appear to be involved in the development, of AD, it is unlikely that treatments targeting any one neuropathological pathway will be successful. Neuro-pathological heterogeneity may impact drug mechanisms and various pathophysiological mechanisms may interact to produce AD. This has led several investigators to suggest that combination treatments, or agents that simultaneously impact different pathophysiological mechanisms, may have greater efficacy than targeting only one specific pathway.Citation77,Citation99 Schnieder et alCitation141 found that tacrine in combination with estrogen was more efficacious than either agent alone in the treatment, of AD. Yet, Sano ct alCitation142 did not find a combination of selegiline and vitamin E to be more efficacious than either agent alone. However, it must be noted that these two agents may impact, similar pathophysiological mechanisms.

Second, accumulating evidence suggests that individual differences in genetic and other risk factors may also affect drug response. Several studies have found a smaller treatment response to tacrine and metrifonatc in AD patients positive for the ε4 allele, although some observed this effect, only in women, suggesting the existence of a gene-gender interaction.Citation93,Citation143,Citation144 However, others have suggested that the impact of ε4 may vary according to therapeutic approach, with studies of other compounds (eg, the noradrenergic compound S12024) observing a better treatment response in ε4 carriers.Citation143,Citation145 Many of these findings arc preliminary in nature, based on data from clinical trials of short duration, with samples sizes that are too small to yield large enough comparison groups of patients with and without the ε4 allele. Data from larger, longterm clinical trials are required to more fully elucidate the role of genetic and other risk factors in treatment response, and it is interesting to note that in a large clinical trial of galantamine, Wilcock et alCitation146 observed no impact of the ε4 allele on drug response.

Finally, variability in stage of illness, patient demographics, drug dose, duration of clinical trial, and other methodological issues also impact drug response. Many randomized clinical trials of newer pharmacological agents include only highly selected populations, and more effectiveness studies are required, which can provide “real world” information. Typically, with respect to the AChEIs, the most efficacious effects have been observed in patients who have used higher doses for longer time periods. Indeed, with respect to agents such as estrogen and anti-inflammatory drugs, where initial results have been disappointing in AD, it is important to note that the short duration of a clinical trial is in stark comparison to the lengths of use found in the epidemiological studies that, have suggested their impact, on AD. Long-term use of such therapeutic approaches may prevent or slow AD onset, but may be far less effective treatments during the acute phases of the illness. This does not necessarily diminish the potential positive impact, of these approaches on the illness itself, and many investigators stress the importance of intervening in the preclinical and early stages of AD where the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents may offer greater promise for preventing and/or delaying rather than treating the cognitive symptoms associated with this illness.

Nonpharinacological approaches to Alzheimer's disease

As emphasized by Reichman,Citation147 pharmacological approaches can be combined with behavioral and environmental interventions that assist patients in maintaining the highest, possible level of function. Patients in the early stages of dementia may benefit from support groups and other constructive environments that provide information and feedback on the cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Attempts to improve cognitive function in AD patients through reality orientation, reminiscence, and memory retraining have had some limited success.Citation148

Reality orientation was developed primarily to reduce confusion and disorientation in dementia patients in institutionalized settings. A key feature of reality orientation is to remind patients of who and where they are, provide feedback on time of day, day of week, etc, comment, on and describe what is happening at a given moment in time, and generally reinforce the patient's awareness of their environment. Recent studies have observed improvements on the MMSE following sustained treatment, with reality orientation.Citation149,Citation150 However, such changes are often observed on the orientation components of the MMSE-, and reality orientation does not appear to significantly impact behavioral functioning and, despite improvement, in cognition, improvements in IADL were not observed in several studies.Citation150,Citation151

There are a variety of memory training techniques that have been employed with some success in nondemented older adults, and we discuss these in detail below. These techniques are typically not effective in patients with dementia since their success relies upon utilization of many of the information-processing systems, which are no longer intact, in dementia. However, prosthetic memory aids such as diaries, memory wallets, and well-placed lists around the house and garden have been found to be helpful, particularly for early-stage patients who can benefit from the type of mnemonic cueing such aids provide.Citation152,Citation153

Reminiscence therapy has also been postulated to be a potentially effective therapy for patients with dementia since studies suggest, that memories for remote events remain intact, longer than other forms of memory. Reminiscence therapy aims to facilitate recall of past experiences with the overall goal of enhancing well-being. Few systematic studies of the effectiveness of reminiscence therapy in dementia patients exist, but the limited data available suggest that this technique may be more beneficial to interpersonal communication than cognitive processing.Citation154-Citation156

Indeed, many of the aforementioned techniques can also frustrate the dementia patient, by underscoring the limitations of their cognitive functioning. Behavioral therapy approaches aimed at, decreasing agitation, negative thoughts, and depression, and improving self-care have been quite successful. Additionally, studies suggest that taking a behavioral management approach to improving the mood and behavioral problems of AD patients may also have benefit for cognitive symptoms.Citation157,Citation158

Although little empirical data exist, there is a clinical consensus that modulating the environment may be very helpful to the AD patient, in particular in ensuring that their daily routine is consistent and their daily environment is not overstimulating. It has also been suggested that providing feedback with respect to orientating AD patients to time of day, place, and person in an informal but consistent, fashion may at the very least alleviate the anxiety associated with loss of cognitive function. Still others suggest that some AD patients may benefit from exposure to the outside world through newspapers, radio, and television. Mittelman et alCitation159 found that providing both information and emotional support, appeared to improve quality of life indices and even delayed nursing home placement. Most recently, the culmination of these views has been reflected in an increased focus on the role of occupational therapy in the management of dementia symptoms. The COPE (Caregiver Options for Practical Experience) study aims to further develop the role of occupational therapists for working with dementia patients. Deficits and strengths in a variety of sensorimotor, cognitive, neuromusculoskeletal, and psychological domains are assessed. Based upon this assessment the occupational therapist, then works with the patient and their caregivers to design individualized approaches to reducing the barriers to optimal functioning.Citation160

Future directions in Alzheimer's disease

Despite the burgeoning research exploring a broad variety of pathophysiological approaches and pharmacological compounds for the treatment of AD, observed improvements in cognitive symptoms have been modest at best, even with the most efficacious approaches. Statistical significance does not, always translate into clinical significance, and improvements on such measures as the ADAS-Cog or MMSE are often not associated with similar improvements on clinical rating scales, measures of IADL, or patient or caregiver ratings of function. Even when improvement or stabilization of cognitive function occurs, such benefits invariably do not sustain. While approaches such as reduction of β-amyloid may yield more efficacious treatments in the future, current approaches are limited. As Skoog and GustafsonCitation161 emphasize, the evidence suggests that secondary prevention is particularly important with respect to AD. Secondary prevention occurs when an illness is detected early, in the preclinical stage, at which point treatment can be implemented to prevent it from progressing to the clinical phase of the illness. Recognition that agents such as estrogen may protect against, rather than treat AD has also fueled the emphasis on the secondary prevention of AD. This view is reflected in an increased focus not only on the early identification of preclinical AD, but also on the classification and remediation of the cognitive and memory problems that occur with age.

Cognitive change in normal aging

Age-related changes in cognition among the healthy are well documented. Several psychometric measures of attention, memory, and reasoning abilities, as well as those emphasizing speed, display particularly robust age-related declines. Less pronounced declines in measures of knowledge, such as vocabulary, are observed with age.Citation162-Citation164

Although much of this information is based on cross-sectional studies, longitudinal sequences from the Seattle Longitudinal Study, among others, confirm the existence of age-related decline on several measures of cognitive performance.Citation7,Citation165 -Citation168 “Data on rates of aging ... suggest that a rapid rise to peak performance in the third and fourth decades of life is followed by a ”continuous decline' which is slight, over the fifth and sixth decades and thereafter rapidly accelerates“ (Rabbitt, 1990).Citation169 While investigators may disagree as to the ages at which decline in cognitive function occurs, there is a consensus in the aging literature that cognition does not decline uniformly across the life span.

One of the clearest, findings to emerge from the field of cognitive aging is that older adults are unable to recall as much as younger adults from long-term memory. Citation162,Citation170,Citation171

Memory difficulties worsen with advancing age and are a major aging complaint.Citation172-Citation174 Many older adults find their memory and cognitive impairments debilitating on a daily basis and find that they interfere with many of their daily activities. It was the recognition of age-associated cognitive decline that, appeared to go beyond that typically associated with normal aging that led to the classification of such problems as AACD and MCI.

Defining normal vs MCI vs pathological aging

Over the past 20 years there have been several proposals regarding how best, to characterize the spectrum of memory function in nondemented older adults. Ferris and KlugcrCitation175 have reviewed in detail the following proposed characterizations: mild cognitive impairment (MCI), age-associated memory impairment (AAMI), and age-related cognitive decline (ARCD). While initial descriptions of MCI suggested that some individuals likely decline on a variety of cognitive domains, more recently, MCI has come to refer more specifically to presence of memory' impairment greater than expected for an individual's age, with general, cognitive function preserved and no other neurological deficit present, that is consistent with dementia.Citation6,Citation174 As many as 1 2% of MCI cases per year have been found to progress to dementia over the course of 4 years.Citation6 AAMI is a concept developed by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) workgroupCitation175-Citation176 attempting to label the memory loss associated with normal aging. The criterion developed by this group for diagnosing AAMI was scores “at least 1 standard deviation below the mean established for young adults” on a normed, standardized test of recent memory. After much debate, ARCD became the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition (DSM-IV) variant, of AAMI and was designed to include both memory and other cognitive changes associated with aging. To ensure that the ARCD label did not, imply pathology, the word “deficit” was eliminated from its definition and ARCD was included in the “Other Conditions” section of the DSM. A major issue left, unresolved was development of specific diagnostic criteria for the application of the term ARCD.

In contrast, to AAMI, age-associated cognitive decline (AACD) measures gradual decline in cognitive function, and uses norms for similarly aged and educated subjects to assess whether an individual, fits the criteria for this classification. Unlike the concept, of ARCD, there are specific criteria for AACD, and cognitive domains other than memory, including attention, problem solving, and language abilities can be involved. The classification for AACD requires a documented decline in a single cognitive function beyond that expected for similar age and education levels, but without evidence of dementia.Citation177

While MCI is typically viewed as representing a preclinical phase of AD, recently, investigators have recently suggested that a greater number of individuals classified as AACD convert to dementia, than individuals with MCI.Citation178 In particular, these investigators question the necessary involvement of a memory impairment in order to be classified as having cognitive decline, arguing that this is too restrictive given the heterogeneity among presenting cognitive symptoms in AD patients. Additionally, the prevalence of AACD, AAMI, and MCI is such that, given the most liberal projections, there is no way that all individuals so classified will, in fact, develop dementia. Yet, many older adults have memory and other cognitive impairments that they find impact their day-to-day functioning, and there is an increasing demand among older adults for therapeutic interventions to remediate such cognitive deficits. This demand has been matched by an increased focus among clinicians, researchers, and pharmaceutical industries on developing pharmacological approaches for the palliative treatment of the cognitive impairments associated with such entities as AACD and MCI.

Perhaps the most controversial issue in separating out normal aging deficits, from AACD and MCI, from dementia is the concept of coexisting pathology. While the cognitive deficits associated with such classifications do not reflect degenerative pathological processes, it is unlikely that they do not reflect, the physiological changes in brain function that are commonly associated with aging. These changes include many of the pathophysiological mechanisms that, in a more severe form, underlie dementia, including neurotransmitter deficiencies, inflammation, and oxidation. As SherwinCitation179 points out in her review of pharmacological treatment, options for MCI, there has been less emphasis on such approaches for the remediation of cognitive problems in nondemented older adults than in AD. Yet, ironically, a significant, number of clinical trials have been conducted to assess the impact of a variety of pharmacological agents on cognition in normal aging, AAMI, AACD, and MCI. Many of the therapeutic approaches to AD have been utilized in such populations, less often to assess the benefits for this population than as the first step in assessing their safety and efficacy for use in AD patients.

Pharmacological approaches in AACD, MCI, and normal aging

Neuro transmitter deficiencies

Cholinergic deficits. Numerous studies suggest that central cholinergic activity declines with age. While profound cell loss from the cortex itself has generally not, been observed, loss of subcortical cholinergic neurons may be associated with normal aging.Citation13 Neurons located in the subcortical basal forebrain region provide cholinergic innervation to the hippocampus and neocortex. Degeneration of these neurons likely contributes to cognitive impairment. An age-related decrease in the presynaptic activity of CAT has been reported in humans.Citation180 CAT is considered a marker of cholinergic neurons; thus its decline with age indicates a loss of cholinergic neurons with increasing age. Since postsynaptic muscarinic receptor binding also decreases with age,Citation181 it appears that both presynaptic and postsynaptic cholinergic degeneration are involved in the process of normal aging.

Baxter et alCitation182 demonstrated in rodents that most of the age-related changes in cholinergic markers were already present at ages at which behavioral impairment, was not yet maximal. A postmortem study in humans, however, somewhat, challenges this finding: cholinergic deficits, measured as activity of the cholinergic enzymes CAT and AChE, were apparent in elderly individuals with severe dementia, but not in individuals with moderate, mild, questionable, or no dementia.Citation183

However, administration of the cholinergic antagonist scopolamine in humans has been found to impair the encoding of information into long-term memory and to impact other cognitive processes.Citation22,Citation184,Citation185 Since a cholinergic antagonist, is associated with impairments in memory and cognition, cholinergic enhancers, especially AChEIs, may ameliorate such impairments.Citation186-Citation188 Cholinergic enhancers (for example, arecoline, a muscarinic agonist, and choline, a precursor of ACh) have been tested on effects on performance of memory tasks in healthy volunteers after administration of the cholinergic antagonist methscopo lamine. Both drugs reversed scopolamine-induced impairment of serial learning.Citation189 Poor baseline performers proved to be more vulnerable to both the enhancing effect, of the cholinergic agonist, and precursor and the impairment after cholinergic antagonist than good performers.

A number of studies of AChEIs in humans of varying ages suggest a broad range of effects on memory and attentional processes. Early studies administering the cholinestera.se inhibitor physostigmine to aged humansCitation190 observed significant, improvement in performance on long-term and recent memory and picture recognition tasks, further supporting a cholinergic role in memory decline with age. Recent studies with newer compounds have found similar effects.Citation191-Citation193

In a recent cerebral blood flow study with healthy human volunteers (age range 22 to 68 years), cholinergic enhancement with physostigmine was associated with improved working memory efficiency, as indicated by faster reaction times and reduced activation of cortical regions associated with working memory.Citation194 Similarly, in a more recent, investigation using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Furey ct alCitation195 found that physostigmine resulted in enhanced neural processing in visual cortical areas during a visual working memory task, particularly during encoding. They conclude that augmenting cholinergic function may improve working memory by enhancing the selectivity of perceptual processing during encoding. Cholinergic drugs have also been associated with improvements on measures of visual attentional function, leading some reviewers to suggest, that, part of the benefit of cholinergic drugs upon memory performance may be mediated through the attentional components involved in working memory.Citation13,Citation21,Citation196

The impact of AChEIs on a range of memory and other cognitive processes suggests that they may represent a valuable approach to enhancing cognitive function in older adults asymptomatic for dementia. An NIA-funded clinical trial of donepezil is ongoing in individuals classified as MCI.

Other neurotransmitter deficiencies. While there are limited data on the impact, of the AChEIs in older adults, there have been several studies examining the impact of modulating glutamate receptors in this population. As mentioned, the neurotransmitter glutamate has been implicated in cognitive function, and has been suggested to decrease with increased age. Direct activation of NMDA receptors has proved problematic, and several investigations have attempted indirect, stimulation via glycine-like agonists such as milacemide. While milacemide has not been found to be therapeutic in AD, studies in nondemented, older adults found that it improved working memory, verbal and visual memory, and attention.Citation197-Citation199 However, in a randomized clinical trial of the glycine agonist, cycloserine, no significant impact on cognition was observed in subjects classified as AAMI.Citation62

In a clinical trial in older subjects, using ampakin es, which target AMPA receptors, Lynch et alCitation60 observed a dosedependent improvement in delayed recall performance. Additional clinical trials with these compounds are in progress.

As mentioned, S12024 facilitates noradrenergic and vaso pressinergic systems and preliminary findings indicate that this compound enhances cognition in older adults with AACD.Citation61,Citation62,Citation200

Inflammation and oxidation

In addition to the documented reduced risk of AD among asymptomatic older adults using NSAIDs, recent, studies have investigated the relationship between use of antiinflammatory agents and cognitive function in this population. In a study of 13 153 individuals, between 48 and 67 years of age, who regularly utilized NSAIDs or asprin, no associations between NSAID use and any of the cognitive tests were observed, although a modest, association was observed between aspirin use and better performance on delayed recall and verbal fluency tests.Citation201 Yet others observed no positive impact of prescription NSAID use on cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults.Citation202

However, as emphasized by Pasinetti,Citation76 daily doses of up to 1200 mg of NSAIDs such as ibuprofen are analgesic but not, anti-inflammatory, and it, typically requires daily doses of 2400 mg for a systemic anti-inflammatory effect. It is interesting to note that in an investigation of the impact of chronic NSAID use on cognitive decline in older adults, Rozzini et alCitation203 found a positive association between chronic NSAID use and reduction in cognitive decline over 3 years, as measured by the Short. Portable Mental Status Questionnaire. As Karplus and SaagCitation204 point out, large-scale, randomized, controlled trials using NSAIDs in this population are needed before it, is clear whether the known risks of NSAIDs are outweighed by their potential long-term benefits on cognition.

There have been several investigations of the impact, of G biloba on cognitive function in adults asymptomatic for dementia. Several of these studies found that G biloba appeared to improve speed of processing and memoryfunction, particularly on measures of working memory.Citation205-Citation207

However, these studies were typically short, in duration, ranging from 6 hours to 12 weeks, and included middleaged rather than older adults. Several, large-scale, multisite, randomized clinical trials of G biloba in older adults arc ongoing and their results should further clarify the relationship between this agent, and cognitive performance in this population.

The influence of estrogen on cognition and memory in normal aging has also received considerable recent, attention.Citation208-Citation214

One of the most, consistent findings to emerge from the above literature links estrogen to the maintenance of memory function in aging women. Several studies found that estrogen significantly improved performance on tasks of both the immediate and delayed recall of verbal and nonverbal material.Citation213-Citation217 While several observational studies have shown that estrogen administration has a positive effect, on attention span, concentration, and memory function, others have not observed an association between ERT and cognitive function.Citation218-Citation220 Methodological differences among these investigations, including variation in the age of subjects and the cognitive tests employed, may account for the mixed results. In particular, there is often inconsistent use of estrogen over time in postmenopausal women, which may impact the outcomes from, such observational investigations. However, recent, evidence from imaging studies lends further support for a positive benefit of estrogen on cognitive functioning. In cortical regions typically hypometabolic in AD, Ebcrling et alCitation221 found that older women who had never taken estrogen exhibited metabolic ratios intermediate to those of AD patients and women on ERT. Similarly, a longitudinal assessment of regional cerebral blood flow changes observed increased flow over time in estrogen users compared with nonusers, particularly in the hippocampus and temporal lobes.Citation222

Since the decision to take ERT may be impacted by education and socioeconomic variables, randomized clinical trials are needed to systematically address the merits of estrogen for cognitive processing in older women. To date, there have been a limited number of randomized clinical trials of estrogen use in healthy individuals, with the majority short-term in duration and often investigating younger adults.Citation215,Citation223 Data from large, long-term, randomized clinical trials in this population are required before we can adequately assess the long-term benefits of estrogen use on cognition as well as its role in AD prevention.

Neuronal degeneration

Several clinical trials with nootropics, such as piracetam, have been conducted in older adults, and a significant positive impact of piracetam on both memory and attentional functions was observed.Citation224-Citation226 Additionally, two studies have investigated the affect, of 4.8 g/day of piracetam on the driving ability of elderly adults exhibiting deficits in psychomotor speed at, baseline. While some investigators found that treatment with piracetam reduced the numbers of errors committed in real traffic, still others observed no benefit of piracetam on driving performance.Citation62,Citation227 The few studies conducted with pramiracetam in this population have also observed improvements in memory performance relative to placebo.Citation228,Citation229

Nonpharmacological treatments for normal aging

Memory training

Studies from several groups including our own have documented the efficacy of providing cognitive training aimed at instructing older adults to use mnemonics for practical problems such as recall of names, faces, and lists. Citation230-Citation234 However, some have criticized such interventions because the effects demonstrated have often been modest and shortterm.Citation235 Furthermore, only a few studies have examined whether the benefits of memory training programs persist for longer periods and these have yielded mixed results.Citation236-Citation238

Additionally, it is unclear whether or not, subjects continue to employ the mnemonic technique acquired and whether this reported use of the mnemonic affects memory function. Several investigators found that at follow-up subjects had ceased to apply the mnemonic techniques acquired.Citation236-Citation238 Yet, in our recent, work, we followed 112 community-dwelling older adults, 4 to 5 years after training and found that 40% of them stated that they employed the training at follow-up. Uhesc participants exhibited better memory performance at follow-up than they had prior to the start of their training. However, those subjects who exhibited the best memory performance at baseline benefited most from, the memory training.Citation239 This suggests that alternative interventions may need to be considered for elderly adults who maybe particularly vulnerable to memory decline with age and who thus do not benefit as effectively from such mnemonic training.

For example, one novel approach to cognitive impairment in older adults has been the attempt to combine pharmacological and memory training. Israel et alCitation240 conducted a double-blind randomized trial of a total of 135 older adults with AAMI. Two intervention methods, piracetam and memory training, were assessed in combination. Une combination of piracetam and memory training resulted in significantly better performance on measures of immediate and global recall than observed with memory training combined with placebo. Additionally, the combined pharmacological and training approach appeared to be most effective in patients whose baseline performance on memory tests was lowest.

Stress reduction

Increases in stressful events accompany increased age,Citation106,Citation241 and several investigators have suggested that life stressors contribute to ARCD. A recent investigation of this relationship found that cognitive decline with age appeared to occur regardless of stressful life events, with the exception of the death of a spouse or child, which was found to be associated with greater cognitive decline.Citation241 However, Crcasey ct alCitation242 observed that, prisoners of war appeared to have a significantly greater percentage of cognitive disorders. Most recently, investigators have suggested that a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be a risk factor for the development of AD.Citation235,Citation243 Although findings from these studies are suggestive, there are methodological weaknesses relating to lack of appropriate control subjects and variation in the measures employed. In addition, none of the above studies included measures of Cortisol response or other measures of HPA activity.

The literature suggests that stress may have an interactive effect with HPA changes with age, resulting in the acceleration of hippocampal atrophy, memory decline, and/or the development of AD.Citation105,Citation106,Citation244 Many investigations have observed increased levels of glucocorticoids in aging animals and humans.Citation106 The observation in animals that prolonged exposure to high plasma Cortisol levels causes irreversible hippocampal damage led to speculations that increased levels of corticosteroids are neurotoxic and that long-term hypercortisolemia may accelerate cognitive decline and the dementia process.Citation103,Citation110 Longitudinal studies indicate that, while some older adults exhibit, decreases in Cortisol levels over time, the greater majority exhibit, increases in Cortisol over time.Citation245-Citation247 These increases in Cortisol also appear to impact cognitive decline. Several recent studies have found increased Cortisol levels in nondemented older adults to be associated with reduced hippocampal volume and with decline in memory function.Citation245,Citation248-Citation251 It has also been suggested that increased levels of the adrenal steroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) protect, against any negative impact, of stress, since studies suggest, that DHEA may enhance hippocampal function and improve memory. Berkman ct alCitation252 found high levels of DHEA to be associated with higher cognitive performance in older adults. However, other investigators observed no such relationship.Citation253,Citation254 However, KalmijnCitation248 found that the ratio of free Cortisol to DHEAS was significantly related to decline on the MMSE over 1 to 2 years in a sample of healthy elderly adults, leading investigators to speculate that a progressive age-related increase of the cortisol/DHEA ratio may induce cortisol-mcdiated hippocampal lesions. Overall, as suggested by Lupien et al,Citation250 impaired HPA activity may be an important, factor contributing to the genesis of memory deficits with age.

However, what is not, clear from the literature is whether chronic levels of recent psychosocial stressors are associated with abnormal or increasing Cortisol response in this population, or how sustained levels of chronic psychosocial stress may impact Cortisol response over time in this population. To date, there have been no studies of the long-term impact of the relationships among ongoing psychosocial stress, HPA axis activity, and cognitive decline in older adults. If stress-associated abnormalities in Cortisol response impact hippocampal function and cognitive decline with age, then this could have significant, implications for the use of both pharmacological, and nonpharmacological approaches, such as systematic stress reduction programs, for reducing this response and thus alleviating cognitive decline.

Physical and cognitive activity

Age-related cognitive changes have long been linked to health status.Citation255 In particular, illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular deficits have been documented to be associated with decline on a broad range of cognitive domains.Citation256-Citation259 Individual differences in genetic and environmental factors may interact with these illnesses to impact cognitive function. For example, presence of the APOE ε4 allele has been observed to increase the risk of cognitive decline associated with arteriosclerosis, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes mellitus.Citation260

However, while specific illnesses are well documented to be associated with increased risk of cognitive decline in older adults, the findings regarding health practices in this population have been more ambiguous. Investigators of the Sydney Older Persons Study examined whether health habits were associated with cognitive functioning, dementia, or AD in subjects aged 75 years or older.Citation261 At, a 3-year follow-up of 327 subjects involving clinical and cognitive assessments, few significant associations were observed between health habits and cognitive performance. No associations were found with dementia or AD. It is important to note that this analysis was based upon self-reports of health habits rather than clinical assessment of health status. Exercise and other physical activity interventions have been shown to improve cognition in older adults. In a randomized trial, Hassmen et alCitation262 found that participants randomly assigned to an exercise group (regular walking, three times a week for 3 months) exhibited significantly better performance than controls on complex cognitive tasks following the intervention.

Most recently, there has been an increased focus on the role of cognitive activity and social engagement in maintaining good cognitive function with age. Investigators of the Victoria Longitudinal Study examined the hypothesis that maintaining intellectual engagement through participation in everyday activities buffers individuals against cognitive decline in later life.Citation263 In a longitudinal study, they examined the relationships among changes in lifestyle variables and cognition. Decreases in intellectually related activities were associated with decline in cognitive functioning. However, as the investigators point out, while their findings suggest, that intellectually engaging activities buffer against cognitive decline, an alternative explanation is that the pursuit of intellectually active lives may be confounded with educational level and socioeconomic status, such that individuals pursuing such activities throughout their life span continue to do so until cognitive decline in old age limits these activities.

Still other investigators have suggested that, social engagement, defined as the maintenance of many social connections and a high level of participation in social activities, guards against cognitive decline in elderly persons. Bassuk et alCitation264 examined the relationship between a global social disengagement scale, which included information on presence of a spouse, monthly visual contact with three or more relatives or friends, yearly nonvisual contact, with relatives or friends, attendance at religious services, group membership, and regular social activities, and cognitive performance as assessed by the Short, Portable Mental Status Questionnaire. These investigators found that individuals with minimal social ties were at increased risk for cognitive decline, and suggested that social disengagement may be a risk factor for cognitive impairment among elderly persons. As with intellectual activities, it is difficult, to know whether lower levels of social engagement reflect rather than precipitate cognitive decline. Further studies are required to more fully address these issues.

Current issues

Many of the same concerns that impact, our interpretation of clinical trials in AD, also limit our interpretation of similar approaches in nondemented populations. As is the case of AD research, individual differences in genetic and other risk factors, such as presence of the ε4 allele or years of education, have been documented to impact cognitive decline with age.Citation7 Such individual differences may also impact response to pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to the remediation of cognitive aging. In addition to the significant heterogeneity among older adults, there is increasing concern regarding the heterogeneity among cognitive assessments typically employed in these populations. While many individuals argue that tests such as the ADAS-Cog and MMSE are not sufficiently sensitive to cognitive change in AD, at the very least these measures are consistently employed in such clinical trials, forming a constant yardstick of measurement, and thus facilitating comparison across trials. However, in asymptomatic older adults, one of the significant confounders in this literature is the extreme variability in the cognitive measures employed across studies. Studies vary not only with respect to the cognitive domains assessed but also with respect to the measures employed to assess the same cognitive domain. Additionally, several investigators suggest that, available neuropsychological measures, traditionally developed with clinical populations in mind, may not be sufficiently sensitive to decline, particularly in high functioning and/or younger elderly adults.Citation265 Such concerns also raise issues regarding the assessment, and subsequent, criteria for such entities as AACD and MCI.

A recent investigation has attempted to evaluate the predictive validity and temporal stability of the diagnostic criteria for MCI. In a longitudinal population study, Ritchie et aiCitation178 found that, using current, classification criteria in the general population, the prevalence of MCI was estimated to be 3.2% and AACD 19.3%. MCI was a poor predictor of dementia within a 3-year period, with an 11.1 % conversion rate. Subjects with MCI also constituted an unstable group, with almost, all subjects changing category each year. On the other hand, subjects classified as AACD appeared to constitute a more stable group, with a 28.6% rate of conversion to dementia over 3 years. Une investigators suggest that the current diagnostic criteria may need to be modified in order to increase their capacity to detect, preclinical dementia.

Another concern with respect, to cognitive decline in aging populations asymptomatic for dementia is how much decline is of clinical significance. Definitions of what constitutes a significantly low score on a psychometric measure vary considerably. In the recent handbook on the neuropsychology of aging, La Rue and SwandaCitation166 propose the following yardstick for at least mild deficit, namely performance ≥1 to 1.5 standard deviations below that of same age peers constitutes a significantly lower score. Yet other investigators argue that cognitive decline is best assessed longitudinally, relative to an individual's baseline performance. Further, while performance on IADL in AD patients tends to be associated with performance on such mental status examinations as the ADAS-Cog and MM.SE, there is only a limited literature attempting to link age-related changes in cognitive performance to functional activities. The Observed Tasks of Daily Living (OTDL) is one measure that attempts to assess the ability of older adults to solve practical problems with respect to various activities of daily living.Citation266,Citation267 Diehl et alCitation266 tested a hierarchical model in which speed of processing and memory span are basic processing resources and different everyday problems require the activation of different constellations of cognitive abilities. Their outcome measure was the OTDL and they found that neither memory nor speed had significant direct effects on older adults' OTDL performance. Indirect effects through the ability factors of fluid and crystallized intelligence were significant. Overall however, much work remains to be done to more fully assess the impact of cognitive decline on complex tasks of daily living.

Future directions in normal aging