Abstract

Auditing failures and scandals have become commonplace. In response, reformers (including the Kingman Review in the U.K. and a recent report of the U.K.’s Competition and Market Authority) have proposed a variety of remedies, including prophylactic bans on auditors providing consulting services to their clients in the belief that this will minimize the conflicts of interest that produce auditing failures. Although useful, such reforms are already in place to a considerable degree and may have reached the point of diminishing returns. Moreover, this strategy does not address the deeper problem that clients (or their managements) may not want aggressive auditing, but rather prefer a deferential and perfunctory audit. If so, auditors will realize that they are marketing a ‘commodity’ service and cannot successfully compete based on their quality of services. Rationally, they would respond to such a market by seeking to adopt a cost-minimization strategy, competing by reducing the cost of their services and not investing in new technology or higher-priced personnel.

What could change this pattern? Gatekeepers, including auditors, serve investors, but are hired by corporate management. To induce gatekeepers to better serve investors, one needs to reduce the ‘agency costs’ surrounding this relationship by making gatekeepers more accountable to investors. This might be accomplished through litigation (as happens to some degree in the U.S.), but the U.K. and Europe have rules that discourage collective litigation. Thus, a more feasible approach would be to give investors greater ability to select and remove the auditor. This paper proposes a two part strategy to this end: (1) public ‘grading’ of the auditor by the audit regulator in an easily comparable fashion (and with a mandatory grading curve), and (2) enabling a minority of the shareholders (hypothetically, 10%) to propose a replacement auditor for a shareholder vote. It further argues that both activist shareholders and diversified shareholders might support such a strategy and undertake it under different circumstances. Absent such a focus on agency costs, however, reformers are likely only re-arranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

1. Introduction

2018 has seen scandal after scandal rack the auditing profession on both sides of the Atlantic.Footnote1 In the U.K., the Carillion debacle has prompted a House of Commons report characterizing the Big Four as a ‘cozy club incapable of providing the degree of independent challenge needed,’Footnote2 and the Financial Reporting Council (‘FRC’) has fined KPMG LLP (‘KPMG’) and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (‘PwC’) for poor audit work and censured KPMG’s poor audit quality (See Collinson Citation2018, Kapoor Citation2018). In the U.S., several KPMG executives have been indicted for allegedly bribing officials at the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (‘PCAOB’) to obtain confidential information about impending inspections by the PCAOB (and one has recently plead guilty).Footnote3 Also in the U.S., the Department of Justice has recently opened a criminal investigation of General Electric’s accounting (which for over 109 years has been audited by KPMG).Footnote4 On the civil side, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (‘FDIC’) successfully sued PwC for its failure to detect $2.3 billion in fraud at Colonial Bank, an Alabama bank that failed after the 2008 crisis, and the trial court this year awarded $625.3 million in damages against PwC (See Yacik Citation2018). Elsewhere, major scandals in South Africa and Denmark have badly tarnished the reputations of the Big Four in those countries.Footnote5 None of the Big Four have escaped involvement in these still developing scandals.

More importantly, at least in the U.K., the current crisis has gone beyond criticism of auditors and the integrity of the audit process. Regulators are now also in the crosshairs. Momentum seems to be developing in the U.K. for potentially major structural reforms, with some political leaders and prominent editorialists calling for ‘breaking up the Big Four.’ Most notably, the U.K. Government has commissioned a study of the adequacy of audit regulation in the U.K. (known as the ‘Kingman Review’ because it was authored by Sir John Kingman), which has recommended that the FRC be replaced by a new audit regulator that would be established by legislation and empowered to tax licensed auditors for its costs and expenses.Footnote6 Simultaneously, the U.K.’s Competition and Markets Authority (‘CMA’) launched an investigation in October 2018 into whether the audit sector was competitive and sufficiently resilient to maintain high audit quality standards, and it also reported on the same date that the Kingman Review issued its findings, again also recommending sweeping changes.Footnote7

In contrast to this urgency in the U.K., the U.S. is still living in the era of Trump, and deregulation continues to be pursued. Although the scandals seem to be evenly distributed between the U.S. and the U.K., the intensity of the reaction has been entirely different.

Why is there this disparity in attitudes? Clearly, the U.K. public wants retribution (and politicians tend to give the public what it wants). Beyond this, however, the looming shadow of Brexit may also have made many in the U.K. nervous that it could risk its status as a financial superpower if it does not tighten controls. Not only is the U.S. not facing the challenge of Brexit, but in the U.S. a litigation system exists that can deal punitively with auditors who underperform. If auditors misbehave in the U.S., they may be disciplined by a very zealous and entrepreneurial plaintiff’s bar, which can (and does) bring securities class actions that result in multi-billion dollar settlements.

In short, in the U.S., private enforcement supplements public enforcement, thus producing (at least in theory) more deterrence. To give but two examples from 2018: Plaintiff’s attorneys convinced a U.S. federal court to order PwC to pay the FDIC $625.3 million in damages as a result of its failure to detect fraud in the earlier noted Alabama bank failure (See Yacik Citation2018), and a federal securities class action in New York resulted in Petrobras agreeing to a $3 billion dollar settlement to which PwC contributed an additional $50 million (simply as the price of escaping an appeal by the plaintiffs in a case that had been dismissed against PwC).Footnote8 In the U.S., the financial penalties and damages likely to be imposed by both public and private enforcement when a scandal surfaces will typically exceed those in the U.K. – frequently by an order of magnitude.Footnote9 Whether or not adequate deterrence actually results from private enforcement in the U.S., the greater size of the penalties in the U.S. stand out strikingly. Thus, precisely because the U.K. (and probably Europe as well) seem unable or unwilling to adopt U.S. style enforcement, they must find some other means of ensuring accountability.

Despite these differences (with greater political anger in the U.K. and tougher enforcement in the U.S.), the underlying problems appear to be much the same. On both sides of the Atlantic (and in Europe and elsewhere as well), the basic model of the auditor has long been that the auditor is a gatekeeper who pledges its reputational capital, acquired over many decades and a multitude of clients, to assure investors as to the reliability of the issuer’s financial statements.Footnote10 The premise here is that a rational auditor will not risk its reputational capital simply to gain an enhanced fee from a single client.

Here, some elaboration is needed. By ‘gatekeeper,’ one can mean just someone who controls access to the ‘gate’ – that is, someone with veto power who can thus perform a policing function. But the contemporary problem with gatekeepers involves a broader conception of that term. In this broader view, a ‘gatekeeper’ is a repeat player who provides certification or verification services to investors, vouching for someone (such as a corporate issuer) who has a greater incentive to deceive. In this view, auditors, securities analysts, credit rating agencies and others are all agents of the investor who act as reputational intermediaries to assure investors as to the quality of the ‘signal’ sent by a corporate issuer. The reputational intermediary does so by ‘pledging’ its reputational capital to the corporate issuer, thus enabling investors (or the market) to rely on the corporate issuer’s representations and disclosures (where in the absence of such a pledge they might not). At least in the U.S., respected judges have endorsed this model, opining that it would be simply ‘irrational’ for a major auditing firm to tolerate fraud because the auditing firm would suffer a reputational loss (and hence reduced future earnings) that dwarfed its audit fee from the responsible issuer.Footnote11 Still, such ‘irrationality’ appears increasingly common today. What explains this? At this point, we encounter a basic disconnect: although auditors serve investors, they are hired by management. To the extent that the interests of investors and management do not align closely, the relationship is one with inherently high ‘agency costs.’ To reduce these agency costs, mechanisms must be found to increase auditors’ accountability to investors. The U.S.’s reliance on litigation may be one such means, but, as later discussed, it does not translate easily (if at all) to the legal systems of Europe and the U.K. Thus, if a given country does not want to utilize litigation as its principal means of holding auditors accountable, it must find an alternative strategy. This paper will suggest that the tailored use of shareholder voting may offer such an alternative means to fill this void.

2. Diagnosis

Initially, this essay will seek to map the most likely explanations for auditor failure and then match these hypotheses with relevant reforms that logically respond to them. In overview, I will group the most common explanations for why the auditor is a less effective gatekeeper today under four headings:

The predominance of consulting income over auditing income inclines the auditor to be more accommodating in order to use its auditing role as both a loss leader and a portal of entry into the client in order to maximize more lucrative consulting income;

Reduced competition and the de facto oligopoly enjoyed by the Big Four may invite the auditor to be less protective of its reputational capital, instead arguably treating it as a ‘wasting asset’; in essence, the auditor may today need less to excel and establish its professional superiority at detecting fraud, and more to accommodate issuer management – at least without becoming caught in a scandal that jeopardizes its reputation for integrity;

Investors may care less today about audited financial information and rely more on other protections and/or other gatekeepers (including securities analysts, credit rating agencies, and activist hedge funds); at the same time, the pervasive use of incentive equity compensation as the primary form of executive compensation may cause the executives at issuers to press ever more aggressively for auditors to defer to their earnings goals; and

In some cases (a minority, to be sure), audit firms or engagement partners at those firms appear to have been complicit in fraud. These cases may represent instances in which audit firms, having exhausted their reputational capital through involvement in prior scandals, survive by deferring to management and exercising little or no professional independence.

The view discussed above that auditing and consulting are incompatible obviously underlies the CMA’s recent report. Still, this paper is agnostic about the adequacy of this and other explanations for audit failure. Each may be true in part, but none is unanswerable. Nonetheless, a pervasive problem does seem to exist with audit quality. To cite just one statistic, in 2017, the International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators (‘IFIAR’) reported finding deficiencies in 40% of the audits its members inspected.Footnote12 Actually, IFIAR thought this was an encouraging sign, because it was down from 47% in a comparable 2014 study. Yet, if a hospital review board found errors in 40% of the surgeries that surgeons working at that hospital had conducted, I doubt that this board would be encouraged (even if the rate was down from 47% a few years earlier). To be sure, there is no perfect or common metric here because these percentages depend on how tough each regulator is and also on how representative are the audits that it inspects. Still, this statistic gives us a starting point that suggests that auditing errors apparent to a regulator are common.

My analysis is marginally different from the standard explanation for auditor failure. The standard critique focuses on oligopoly and conflicts of interest as its explanation for why the auditor has underperformed. But it is also possible that the auditor is doing exactly what its corporate client wants: that is, providing a deferential, even cursory, review of the issuer’s financial statements that raises few problems. The deeper problem then is not that competition is limited or that the desire for more lucrative consulting work creates a conflict of interest, but that the client, itself, does not want aggressive auditing and outsiders (including investors) cannot distinguish superior from mediocre auditing services. Knowing this, the major auditing firms (or at least some of them) may have decided that auditing is a ‘commodity’ business in which one cannot successfully compete based on the quality of one’s services, but only based on client accommodation and low cost. The net result is to produce a common focus on cost minimization: how can the audit firm maximize its revenue by minimizing its effort and investment?

That is a harsh diagnosis, but it poses an even harder question: what might work to change this status quo? This article’s answer is that we need to reduce the ‘agency costs’ surrounding the auditor/ investor relationship.Footnote13 Although there may be multiple means to this end, the fact that the U.K. (and probably Europe as well) are disinclined to rely on a deterrence focused strategy (which, to be sure, has been far from an unqualified success in the U.S.) implies that some other means must be found to change the incentives of audit firms. Two principal means to this end will be assessed: (i) giving investors a greater role in the selection and removal of the auditor, and (ii) introducing a more transparent system under which the audit regulator reviews the auditor’s performance and publicly communicates its evaluation in much clearer language than is used today. This would require formally grading the auditor’s work and publicly communicating this ‘grade.’ To some degree, this would also require asking the auditor to make additional judgments that would frankly require it to exercise discretion, but in a manner that investors could understand and evaluate. These two ideas fit together, because it is only when investors are both authorized and incentivized to select and remove the auditor that auditors will feel the need to compete based on their quality of services. To make competition produce a race to the top, not the bottom, requires that the audit regulator grade the auditor and then give shareholders a greater decision-making role. At that point, auditing would cease to be a ‘commodity business.’

2.1. The auditing/consulting balance

For decades now, the most popular explanation among reformers for audit failure has been the claim that the pursuit of lucrative consulting work inclines the auditor to be overly accommodating and deferential to its clients’ managements. But in both the U.S. and Europe, significant restrictions have been imposed on consulting services, leading one to question whether this factor can still remain the primary explanation for auditing failure. In the U.S., in the wake of the Enron and WorldCom accounting scandals, Congress enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (‘SOX’), which prohibited auditors from providing nine specified non-audit services to their audit clients and further required that the provision of other non-audit services to the audit client had to be specifically approved by its audit committee.Footnote14 More recently, the European Union followed a functionally similar approach by capping non-audit fees at 70% of the audit fees for any given client.Footnote15 Thus, although the desire to obtain lucrative consulting work from an audit client could still have some influence on the auditor, audit fees will always overshadow consulting income in the case of any individual audit client.

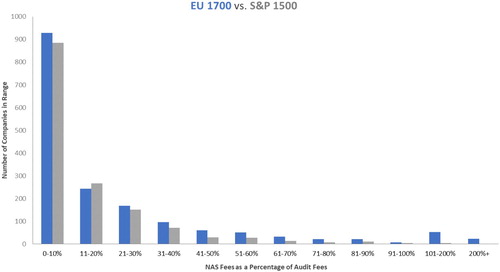

What has been the reaction to these reforms? A study this year by John Pakaluk looked at the ratio of non-audit fees to audit fees for both the US and EU companies in 2017 (See Pakaluk Citation2018). Specifically, he compared the S&P 1500 (which consists of a large-cap 500, a mid-cap 400, and a small-cap 600) to a sample of 1700 European companies, which were included in some 38 large, mid, and small-cap indices across exchanges in some 21 European countries. As shown below, in the case of the vast majority of companies in both Europe and the U.S., non-audit fees fell well below the 70% European fee cap, with the majority of firms having non-audit fees fall in the under 10% range. To be sure, particularly in the U.S. (which has no percentage ceiling), some companies did have non-audit fees over 200% of audit fees, but these cases were very few, as next shown ():

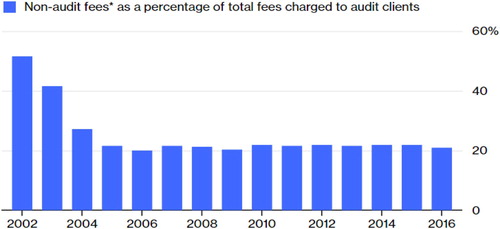

Even in the U.S., which has no percentage ceiling on non-audit fees, the ratio of non-audit fees to audit fees has remained stable for a decade at around 21% (as shows):Footnote16

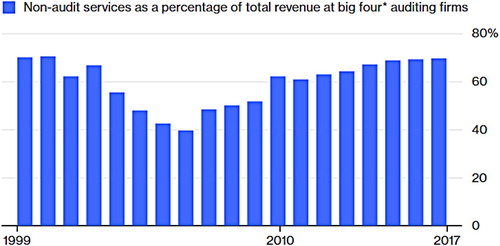

But this does not end the debate. In recent years, the Big Four have re-entered the consulting business in a major way – by supplying these services to companies that they do not audit. As shown below on , non-audit activities have risen rapidly since 2006 and, as of 2017, constituted approximately 70% of the total revenues of the Big Four (up from as little as forty percent after the passage of SOX):Footnote17

This finding has several possible implications. If the consulting side of the Big Four accounts for at least 70% of the firm’s revenues, the consulting side will likely dominate in internal governance decisions within these firms, and the old culture of auditing may be subordinated to the values and style of the consultants. The public-service watchdog role of the auditing side, with its commitment to an attitude of ‘professional skepticism,’ may thus be sacrificed. From the perspective of the consultants, auditing may be seen as a low margin ‘commodity’ business, which justifies little investment. In effect, auditing is (at least to them) a loss-leader that is best used to attract clients. Predictably, the younger generation within the firm will pick up such an attitude and seek to escape the audit side for the ‘greener pastures’ of consulting as soon as possible.

Still, the existing empirical evidence is currently thin to weak for any claim that the dominance of consulting revenues at audit firms today adversely affects audit quality. In a 2017 study, Lisic, Myers, Pawlewicz and Seidel examine the relation between the proportion of consulting revenue received by an auditing firm and audit quality (See Lisic et al. Citation2017). They find that, before the passage of SOX, higher proportions of audit firm consulting revenues ‘negatively impacted both audit quality and investor perceptions of audit quality.’Footnote18 Yet, following SOX, they do not find any ‘statistically significant association between audit firm consulting revenues and either audit quality or investor perceptions of audit quality.’Footnote19 Of course, post SOX, most of this consulting income is not coming from audit clients (at least in the typical case).

Consulting income is not the only source of potential conflicts that could limit an auditing firm’s independence. The U.K.’s CMA has found that two-thirds of the chief financial officers in large listed and private companies were alumni of the Big Four (See Carillion Report Citation2018). The implication here is that an individual auditor may seek to accommodate the issuer’s management in the hopes of joining it at a high level.

From a policy perspective, any discussion of possible reforms might begin by asking why do consultants remain within the audit firm, when they could simply leave en masse (as Accenture once exited Arthur Andersen). Presumably, the logical answer is that consultants have not left the audit firm because it benefits them to stay within it, probably because of the firm’s high reputational capital. Put simply, the names of the Big Four are household words, globally recognized and respected. If the consulting side therefore wishes to remain wedded to the auditing side, this suggests a reform strategy for capitalizing on this preference, which we will turn to shortly.

2.2. Reduced competition (or the competition in laxity)

It used to be the Big Eight; now, it is the Big Four. The evidence of oligopoly is clear.Footnote20 Indeed, there may be even less competition than the number four suggests, because each of the Big Four specializes. A global bank may perceive that only one or two firms in the Big Four has the scale and expertise to handle its auditing. Also, one or two of the Big Four may already serve that bank as a high-paid consultant (and would have to surrender that lucrative consulting it if became the firm’s auditor). In short, audit firms that are enjoying lucrative consulting relationships with a client may not be willing to serve as its auditor (if the client were to decide to replace its current auditor); thus, competition for the audit position may be very limited.

But this focus on the limited prospect for competition may miss a more important issue: In what direction does competition move audit firms? Does it make them more conscientious and unyielding? Or rather more tolerant and accommodating? If a Big Four firm is run by sales-oriented executives from the consulting side of the firm, their desire may be to use the audit business as a loss leader by which to gain a foothold within a large firm in order to sell consulting services. Ultimately, the audit firm could even rationally decide to cease to be the client’s auditor in order to outflank the E.U.’s 70% rule and market more lucrative consulting services in excess of that limit.

Phrased differently, it is uncertain whether a reputation for toughness and rigor as an auditor is today more an asset than a liability for the audit firm. To the extent that the issuer’s management is chiefly compensated through stock and option awards (as later discussed), it has an enormous incentive to prefer an auditor that will let it maximize short-term earnings by bending accounting rules on revenue recognition and other matters.

From this perspective, mandatory rotation of the auditor may not be the optimal reform because it may increase the opportunities for management to select the most flexible and accommodating of replacement auditors. What is instead critical is who really selects the incoming auditor – management, independent directors, or the shareholders, themselves. This in turn frames the question of how to incentivize and induce the audit committee to engage in closer monitoring (and more frequent replacement).

2.3. How much do investors rely on the auditor?

Although conventional wisdom assumes that investors rely on the auditor, this cannot easily be proven because the audit report is required by law in both the U.K. and the U.S. (at least in the case of public companies). Possibly, sophisticated investors have come in recent years to rely more on the projections of securities analysts (which are forward-looking and thus more relevant to firm valuation). Conceivably, if their company seems troubled, investors will place greater weight on credit-rating agencies or activist hedge funds (which increasingly offer detailed critiques of the issuer’s business model and solicit support in proxy contests to change the board and its policies). Investors may give closer attention to these proposals than to the footnotes to the financial statements because these other advisors offer clear choices (and the investors’ votes can be decisive). In contrast, hints in the audit report that there are problems underlying the financial statements offer no such choices.

The implication here may be that to make the audit report more relevant, it needs to frame choices. As a means to this end, it could seek to facilitate a dialogue with investors, first by addressing some questions that require qualitative, even subjective, responses (‘How does the auditor rate the company’s internal controls relevant to those of other companies?’). Conceivably, the auditor could be required to respond publicly to questions framed by the audit committee, other board members, or possibly even some specified percentage of the shareholders. We will return to this theme later.

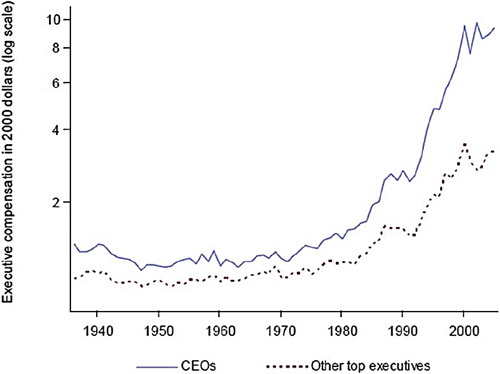

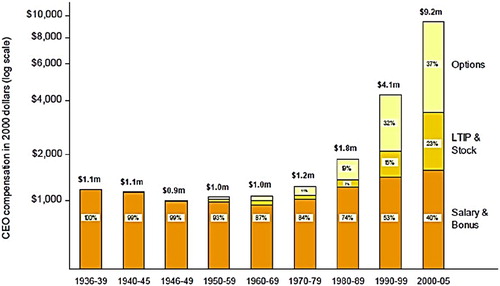

Alternatively, even if we have no doubts that investors remain very interested in the audit report, the possibility exists that management has simply become more adamant in recent years that the auditors must defer to management’s desire to maximize income in the short term. Such ‘short-termism’ (a popular diagnosis today) seems most likely to be caused by a major shift in executive compensation that began in the late 1980s. below shows the sudden acceleration in the median compensation of CEOs and other top officers from 1940 to 2000 (See Frydman and Jenter Citation2010).

Clearly, there is a major inflection point in the 1990s. What caused it? below shows that a shift from cash to equity compensation bears the principal caused responsibility (See Frydman and Jenter Citation2010):

As of 2015, Equilar, a consulting firm specializing in this area, reports that the share of total CEO compensation deriving from equity was 60% for companies in the S&P 500 (See Equilar Citation2016). The implication here is that management will want the auditor to support its stock price (whereas a cash-compensated management team will feel this need much less urgently).

2.4. Principal/agent problems and rogue auditing

Some evidence in recent scandals suggests that the management of audited entities have pressured the auditor to the point that the individual auditor or the firm (or both) were complicit in knowing fraud. That is, the auditor or the firm was not accused of a lack of competence or negligence, but, more fundamentally, of disloyalty and deceit.

A glaring example arose in South Africa, this year, where KPMG had represented for many years the Gupta family, a wealthy family with very close connections to South Africa’s government. Essentially, substantial sums (R6.9 million) were diverted from a Gupta-owned firm, Linkway Trading, to pay for the wedding of a Gupta family member.Footnote21 An auditor aware of such a diversion cannot plausibly claim that he made a simply negligent mistake, but rather has been complicit in a blatant fraud. Indeed, in early 2018, South Africa’s Companies and Intellectual Property Commission filed criminal charges against KPMG South Africa as a result of this transaction. Some nine senior executives at KPMG South Africa resigned from the firm. Meanwhile, South African companies have begun to sever ties with KPMG (See Doherty Citation2017).

If this were not trouble enough, KPMG encountered similar problems in South Africa in its relationship with VBS Mutual Bank, which failed in 2018. An investigation concluded that VBS was ‘corrupt and rotten to the core’ and recommended that a claim be instituted by the Prudential Authority against KPMG (See Motau Citation2018, Marriage October Citation2018). Even more revealing, the engagement partner for KPMG on the VBS audit had been lent substantial funds by VBS at below market rates (and without the knowledge of KPMG).Footnote22 This at least sounds like a bribe.

3. Prescription: what might work?

Gatekeeper failure is not a new phenomenon. Following the IPO crash in the U.S. in 2000 and 2001, Congress concluded that both securities analysts and auditors had failed to maintain their professional independence and took various actions in SOX. In the case of auditors, Congress replaced private self-regulation with public regulation through a new regulator, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (‘PCAOB’). After the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. Congress turned its attention to credit rating agencies and enacted reforms in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. Today, as fissures seem to be widening in the foundation underlying the gatekeeper model for the auditor, re-thinking of the auditor’s role is again needed. One can no longer assert with confidence that the auditor acts as a reputational intermediary who pledges its reputational capital to assure investors as to the reliability of the issuer’s financial statements. Logical as that claim may be, it is not proof, and ideas have to be tested.

Viewed objectively, this theory of the auditor as a reputational intermediary could prove to be overly theoretical and illusory for a variety of reasons, including:

Investors may no longer rely as much on auditors today either because (1) they see auditors as ‘captured’ by the issuer and thus independent in name only, or (2) investors may care less about historical financial data and more about the forward-looking estimates and projections of the security analyst;

Investors may be unable to distinguish superior auditing from inferior auditing because the entire process is opaque;

An individual auditing firm could have exhausted its reputational capital because of involvement in repeated scandals and survives simply on its low cost, accommodating approach to auditing; or

Because the market for auditing services for publicly held firms in the U.K. resembles an oligopoly, the rational audit firm may only need to ensure that its reputation does not fall substantially behind its few rivals; that is it is only a relative decline in reputation, not the overall strength of its reputation, that matters.

One should be cautious about accepting any one of these possibilities as a general proposition. The fact that younger and smaller audit firms have not been able to compete with the Big Four very successfully suggests that the Big Four still possess substantial reputational capital. Clients retain the Big Four (and pay higher fees to them) to satisfy investors (who remain skeptical of less well known firms). Also, it is clear that when an auditor does become subject to major or repetitive scandals in a country, some of their clients do back away, suggesting that reputational capital can be depleted and that scandals do cost the audit firm clients.Footnote23

If one believes that investors have lost confidence in the audit process, one answer may be to make the process more open and transparent and also more rigorous, in part by ending ‘pass/fail’ grading in favor of a more thorough evaluation of the issuer’s financial position and in part by using the audit regulator’s own evaluation of the auditor’s performance as a trigger for other sanctions (including mandatory rotation of the audit firm). If one believes that individual audit partners have violated their firm’s own policies out of loyalty to the client, then narrower remedies, such as mandatory rotation of the audit partner, may be more appropriate.

At present, the FRC does make its audit quality reviews public, but little information is revealed because the grades are relatively terse.Footnote24 Providing a fuller evaluation may encourage investors to place greater confidence in the integrity of the audit regulator and the auditor.

Still, there is a grimmer possibility that would necessitate more sweeping reforms: audit firms may have decided that auditing is a ‘commodity’ business where they cannot compete based on the quality of their services, because their clients want deference more than professional quality. To the extent this view is deemed plausible, the only remedy that will work is to give the shareholders a greater role in the selection of the auditor.

3.1. Comparing audit regulation in the U.S. and Europe

The U.K.’s FRC and the U.S.’s PCAOB are roughly comparable bodies, both responsible for monitoring the quality of accounts published by public companies and the quality of the audit of listed companies and other major public entities (‘PIEs’).Footnote25 Both are members of the International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators (‘IFIAR’), an independent and nonprofit organization dedicated to enhancing audit oversight globally, which was established in Paris in 2006 by audit regulators from 18 jurisdictions and which has now grown to have 53 members around the world.Footnote26 European audit regulators and the European audit process are governed by the E.U.’s Statutory Audit Directive, which was first adopted in 2006 and most recently amended in 2014.Footnote27 Thus, the FRC is representative of most European audit regulators.

Despite many similarities, the FRC (and, by extension, similar European bodies) differ from the PCAOB in exercising authority through a number of delegation agreements with ‘recognized supervisory bodies,’ most notably the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales (‘ICAEW’), which in turn licenses the majority of audit firms (including the Big Four) (See ICAEW Representation Citation2018). All U.K. audit firms that audit listed companies are subject to Audit Quality Review by the FRC. Larger firms appear to be inspected annually. This process, common to Europe, essentially parallels the audit review undertaken by the PCAOB.

But there are differences. U.S. public companies must also undergo an annual audit of their internal controls, and the PCAOB monitors this audit as well. The PCAOB also has broader enforcement powers than the FRC (as the ICAEW, itself, recognized in its 2018 submission to Sir John Kingman in connection with his continuing review of the FRC).Footnote28 Beyond these differences, the U.S. relies on private enforcement of law to a far greater degree than does the U.K. or any European country.

Whatever the reason, the perception in U.K. (in the FRC’s words) is one of ‘falling trust in business and the effectiveness of audit.’Footnote29 This has led both the FRC and the CMA to propose a ban on audit firms earning lucrative consulting fees from issuers that the firm also audits (See Collinson Citation2018). This would effectively supersede the E.U.’s 70% ceiling with a flat prohibition. In the U.S., such a prohibition on consulting applies only to a limited number of statutorily listed non-audit services (and auditors may have found ways to outflank some of these prohibitions).Footnote30

The FRC’s proposal is at least consistent with the limited empirical evidence and does not seek to ban consulting income that is received from non-audit clients. Of course, some might argue that such a universal prohibition would encourage greater competition among audit firms because today an audit firm that is a consultant to the issuer may not want to become its auditor (as this would require the sacrifice of consulting income). But, as noted earlier, there is little convincing evidence to date that consulting fees from non-audit clients affects audit quality at audit clients.Footnote31

Thus, to sum up the existing differences between the U.S. and the U.K., the PCAOB has somewhat stronger enforcement authority than the FRC; auditors in the U.S. audit the adequacy of internal controls; and the U.S. legal system permits broad, ‘opt-out’ securities class actions that can be brought against an auditor, thereby unleashing private enforcement. In contrast, the U.K. may soon adopt a more prophylactic rule than the U.S., which would prohibit audit firms receiving any consulting fees from an audit client. Still, it lacks the enforcement powers of the SEC (in particular, the ability to deal with the issuer’s directors and management).

3.2. What else should be considered?

Given that the current evidence suggest that, in both the U.S. and the U.K., most issuers do not use their auditors as consultants to a significant degree,Footnote32 the FRC’s proposal to bar auditors from serving as consultants to audit clients, even if desirable, will not produce any revolutionary change. Put differently, the point of diminishing returns may have been reached with respect to restrictions on consulting income. If so, what other changes (which could be complements rather than alternatives) should then be considered?

(1) Litigation. An obvious possibility would be to authorize U.S.-style securities class actions. But this is well beyond the scope of the FRC’s authority. Moreover, it would require wrenching changes in the English legal system, which not only does not authorize an ‘opt-out’ class action, but forbids contingency fees and imposes a ‘loser pays’ rule requiring fee shifting (both of which rules are highly inconsistent with a U.S.-style system of private enforcement through class actions).Footnote33 The Bar in the U.K. can be expected to resist any such change vigorously. Thus, private enforcement as a means by which to hold the auditor accountable is not realistically within reach at this time.

(2) A Stronger Investor Role in the Selection of the Auditor. Let us start from the realistic premises that (a) management, not the shareholders, actually chooses the auditor, and (b) many managements would prefer a perfunctory audit that does not intrude on or challenge their judgments. If so, a possible answer is to give shareholders a greater role in the selection of the auditor. One means to this end would be to allow some percentage of the shareholders to nominate an alternative auditor that a majority of the shareholders could opt for in a proxy contest. Suppose, hypothetically, 10% of the shareholders could make such a nomination by a given date each year. Would they rush to do so? Under many circumstances, this is unlikely; diversified shareholders are not eager to incur costs (particularly to benefit other non-paying shareholders) and will under many circumstances remain passive.

But this is not always true. Although diversified shareholders (such as large asset managers and mutual funds) tend not to become involved in firm-specific issues (because their large portfolios make such involvement too costly), they are much more likely to become involved and active with respect to generic issues that arise across their portfolio. Thus, today, the largest asset managers and mutual funds in the U.S. (e.g. BlackRock, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust, and The Vanguard Group) do actively participate in issues involving climate change, board diversity, or corporate governance, because these are issues that constantly arise (and in a similar fashion) across their portfolio. Thus, they can formulate general policies at low cost because they enjoy economies of scale. Choice of the auditor is a similar issue because diversified investors can easily acquire sufficient information regarding the limited number of available auditors.

Even if it were the case that diversified investors would remain passive as investors, other shareholders have a strong preference for activism. In the U.S. today, there are over 100 large hedge funds whose business model is to specialize in activism. Typically, they search for underperforming companies where they believe a change in management and/or business policies will yield a short-term shock price increase. Having identified such a target, they buy a substantial stake (usually, under 10%), solicit allies to do likewise (thereby assembling what is called a ‘wolf pack’), and then seek board representation. Often, their goal is to force a sale, divestiture or merger. Their ultimate success depends upon their ability to convince diversified shareholders to support them, but at least when they win the support of the major proxy advisors (i.e. Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis & Co.), they have recently been highly successful. All the recent evidence shows that activists’ engagements with public companies are accelerating worldwide.Footnote34

Suppose then that the shareholders in a troubled corporation have experienced a significant restatement or other accounting-related crisis. Suppose further that an activist shareholder perceives that seeking to replace the auditor could be a useful tactic in its broader campaign to obtain board representation for itself and its allies. Suppose finally that the activist convinces the major proxy advisors to support it. Now, a low threshold (such as 10%) at which it could nominate a new auditor presents a real opportunity. Moreover, there is evidence that shareholders today will vote to oust an auditor who has performed poorly.Footnote35

At present, the U.K.’s Companies Act provides for shareholder ratification of the board’s or audit committee’s choice of auditor and gives responsibility to both the board and the shareholders to appoint the auditor under different circumstances, but it says nothing about the shareholders voting to replace the auditor.Footnote36 In this light, a provision in a company’s articles of association authorizing such a replacement by shareholders (based on a specified nomination procedure) would not seemingly contravene the Companies Act. Even if the Act were read to authorize the board to overrule the shareholders’ choice of auditor, it would be the rare board that would dare to overrule its own shareholders (particularly if a hedge fund activist was waiting in the background).

Who could the shareholders find as a replacement auditor? It seems unlikely that a Big Four firm would agree to challenge a fellow Big Four firm. To do so would invite counter-challenges at their own clients. Also, it may be more lucrative to be a consultant to that client, rather than its auditor. Still, audit firms outside the Big Four might be more than willing to serve. Indeed, this might be the one route by which the current oligopoly within the auditing profession could be loosened.

The key point here is that competition for the favor of investors (rather than management) seems the one change that could cause audit firms no longer to see their core business as a ‘commodity’ business. Such competition encourages auditors to invest in their reputation for toughness and rigor. To be sure, no basic transformation is likely until some shareholder votes do change auditors. Nonetheless, this is the one reform that could produce a race to the top, rather than the bottom.

(3) Grading. Today, the FRC (possibly with assistance from the ICAEW) does ‘grade’ auditors in terms of audit quality.Footnote37 But what happens to this grade? The issuer’s audit committee may see and discuss it, but the public learns little from the opaque grades that are currently given. Pass/fail grading communicates little meaningful information. This frames an opportunity.

What might be done? Multiple goals are attainable here. First, a fuller grade with an explanation from the FRC may cause the audit committee to respond appropriately, or, when disclosed, the dialogue between the FRC and the audit committee might lead investors to take a greater interest in auditing. Second, release of the grade could be used as an effective sanction, one that could induce the auditor to upgrade the rigor of its audit, even if in so doing it offended its issuer client.

If one gives priority to creating an effective sanction, not only should the rule require full disclosure of the grade and the associated evaluation, but one could tie a poor grade (possibly over multiple years) to a variety of other sanctions. For example, a repetitive low grade could lead to (1) mandatory rotation of the auditor; (2) mandatory rotation of the audit partner; (3) restitution of some portion of the audit fee on the grounds that it was not properly earned; or (4) a prophylactic ban on consulting services by the auditor (both to audit clients and others). Indeed, the ultimate death sentence might be to tell a deficient auditor that it could not take on new audit clients for a specified number of years. The strategy here should be a steadily escalating series of sanctions that compel the auditor to perform its audit with greater care and diligence. Indeed, the threat of taking away consulting (even for non-audit clients) should lead the consultants within the audit firm to also pressure for a stronger audit for their own protection. To paraphrase Dr. Johnson, knowledge that consulting will be banned in the event of another low grade ‘focuses the mind wonderfully’ – like the knowledge that one is to be hanged in a fortnight.

To be sure, even without such options, the FRC could simply take away the auditor’s license. But in a world of only four large auditors, this arguably might reduce competition undesirably or even destabilize the market for auditing services. Thus, lesser, but escalating, sanctions might be easier to impose. The nuance here is that their approach would be known to the audit firm, thereby giving it a strong incentive to improve its engagement with a specific client. To visualize the difference, imagine that the audit of a particular client has been graded as deficient for two years in a row. But the auditor’s audit of other clients has been entirely satisfactory. License revocation here would seem overbroad, but a sanction such as mandatory rotation would be more likely to fall only on the culpable actors. License revocation might still be appropriate in cases of broad, multi-client failure, but a focus on the specific auditor/issuer relationship makes better sense.

(1) Dialogue with the Audit Committee. The auditor may sense (in at least some cases) that the issuer does not want a robust audit (and is reluctant to pay for one). As a result, even under pressure from the FRC, the auditor may continue to provide a relatively perfunctory audit. How can greater pressure be focused on the audit committee? One possible means may lie in sending the FRC’s annual evaluation of the auditor to the client’s audit committee and, when this evaluation shows deficiencies, asking for a response from the audit committee. In essence, the question posed would be: What do you intend to do about this?

Today, the FRC lacks authority over directors. But the proposals in the Kingman Review would change this. The FRC (or its successor) could be given authority to determine whether directors were sufficiently experienced and skilled to be members of the audit committee. How they responded to inquiries from the FRC could be a major factor in that evaluation.

To be very clear, it is not suggested here that the FRC could disqualify directors from serving as directors (that would seem to be the prerogative of the shareholders), but it could find specific directors (or an entire audit committee) to have been inadequate. In such event, it could require the company to select a new audit committee.

(2) Dialogue with Investors. A more controversial option would be for the FRC to disclose to the public its full evaluation of the auditor’s report and the audit committee’s response (if any). To the extent that not all audits are reviewed by the FRC, this approach would lead to the objection that the audit reports so released were unrepresentative, and thus this might present similarly situated auditors in very different lights. Still, over time, these differences would average out, and investors would gain valuable information. The hope here is that disclosure of the FRC’s grade and its fuller evaluation would induce the issuer (and particularly its audit committee) to take the FRC’s comments seriously and respond to them. The result is to enhance the audit regulator’s influence.

Another predictable objection will be that release of critical comments by the audit regulator suggesting that the audit was less than adequate will spook the market and thereby injure investors. But this argument cuts both ways. Aware that the regulator’s adverse comments on the audit report will be released to investors and that such disclosure might affect stock prices, issuers might place less pressure on auditors to accept dubious accounting positions and recognize the need for an independent audit. From an ex ante perspective, less accounting irregularities would result.

(3) Expanding the Auditor’s Role. Many believe the U.K. needs to strengthen the internal controls at U.K. listed companies in the looming shadow of Brexit to assure its continued position as a financial superpower. Others believe that the auditor’s role has been diminished and become perfunctory. Still others focus on the auditor’s expanded role in the U.S. (where the auditor reviews and evaluates the public company’s internal controls) and believe that the U.K. should follow its lead (at least to some degree). From any of these perspectives, a case can be made for requiring the auditor to engage in some type of evaluation of the issuer’s internal controls (although not necessarily a full scale audit).

What would be the impact of such a change? Of course, it would impose additional costs on issuers (and yield enhanced income for auditors), but recent scandals have suggested failures in internal controls that may justify such a step. Second, it would enhance the professional status and standing of the auditor, making it a truer ‘gatekeeper.’ Arguably, investors would rely more on the auditor, because it was now not just a ‘bean counter,’ but a sophisticated evaluator of risk.

Of course, a reply is foreseeable: if auditors fail at ‘bean counting,’ why would they do better at evaluating internal controls? Will they not again be passive and deferential (particularly given that the issuer will be paying them even more)? Several answers are plausible. One answer might be that if the FRC were to grade the auditor’s performance as deficient at both functions and if the FRC is prepared to require mandatory rotation after some period of underperformance, the auditor will face a starker threat (because it now has more at stake), and thus it can less afford to be deferential. Another answer might be that if investors care more, under this expanded regime, about what the auditor does, they will also care more about who the auditor is (and may place more pressure on the audit committee regarding the choice of the auditor and rotation). Today, competition among auditors seems a weak force because (a) auditors have little desire to compete, and (b) investors have little information about auditor performance. In short, as we enhance the status of the auditor and provide more information about its performance, we also increase investor interest and capacity to judge.

Finally, given that over 70% of the revenues at auditing firms comes today from consulting, it is likely that consultants dominate the firm’s leadership, and some may see auditing as a low margin ‘commodity’ business that does not justify significant investment. They may ask themselves: why should we expend more assets, time, and effort, looking for minor discrepancies or debatable judgments, when the client (the issuer) really wants only a quick and deferential review? Yet, the U.S. experience shows that adding internal controls review made auditing a considerably more profitable business and thus may justify greater efforts to protect the firm’s reputational capital. This argument works if, and only if, enforcement is also tightened, so that this enhanced position can be lost.

3.3. What won’t work?

Both the Kingman Report and the CMA have proposed new approaches, but these approaches may not necessarily respond to the deeper, underlying problem that the client does not want a rigorous, independent audit.Footnote38 In that light, let us thus review briefly some of the ideas that have surfaced regularly in the current debate:

(1) Joint Audits. Advocates of this approach believe it will train smaller audit firms outside the Big Four so that they can in time compete and become the auditors for major firms. But will it have this impact? It seems equally possible that Big Four firms will form de facto partnerships with smaller firms with the implicit understanding that the smaller firm will not challenge the Big Four firm in the future. All that we know for certain is that France has used joint audits since the 1960s and that French issuers pay ‘significantly more’ for their audits than do U.K. issuers (See Masters Citation2018).

The ‘joint audit’ proposal is not demonstrably ill-conceived (because the audit regulator could eventually insist on the use of the smaller firm at the time of mandatory rotation), but it does seem less a reform than a Full-Employment Act for auditors.

(2) Audit Regulator Supervision of Auditor Appointments. This idea is also given considerable prominence in the CMA report, but it is less than clear what it means. If it means that the audit regulator will select any replacement auditor (such as on a mandatory rotation), that raises the question of whether they are the better decision-maker than the shareholders. Moreover, if shareholders are invited to rely on the audit regulator, they may have less incentive to take on this responsibility themselves.

In all likelihood, the audit regulator will only focus on the possible appointment of a new auditor at the time of a mandatory rotation. In contrast, the shareholders might decide on any annual appointment to select a different auditor.

Realistically, bureaucracies do not always remain vigilant. When a new reform is introduced, they may be attentive and pro-active at first, but over time they slip back to a business-as-usual pace.

Ideally, both the audit regulator and the shareholders should see the choice of the auditor as an important decision in which they want to be involved. Above all the audit regulator needs to encourage the shareholders to be active and should not act as a substitute for them.

(3) Mandatory Rotation. Although this is a necessary element in any package of reforms (and does not yet exist in the U.S.), it is no panacea. The danger, of course, is that if management dominates the process, it may seek the most accommodating and deferential of the various candidates for the position of replacement auditor. To counter this, the audit regulator should communicate with the leading institutional shareholders to see if they want a role and a voice in the process (possibly encouraging interviews of the rival candidates before these shareholders).

4. Conclusion

To restate the core idea, gatekeepers exist in a principal/agent relationship with the investors who rely on them. But it is generally management who hires and fires them. This anomaly sets the stage for this paper’s principal prescription: to reduce high agency costs, gatekeepers need to be made more accountable to investors by giving the latter a greater role in their selection and removal. Nonetheless, recent efforts at reform have focused instead more on reducing the conflicts of interest to which gatekeepers are subject. That is useful, but misses the greater need to empower the true principal to choose. In the past, such reforms were overlooked because shareholders were assumed to be dispersed, passive and incapable of collective action. With the rise of institutional investor activism, that is no longer true. This new force needs to be harnessed and put to work.

What then won’t work? Although it may be desirable to deny auditing firms the ability to provide consulting services to their audit clients, the likely impact of such a reform at this point will probably be modest. The point of diminishing returns has been reached in terms of what restrictions on consulting can accomplish. More is necessary before auditing firms are likely to compete in terms of the quality of their audit services. Here, auditors are not unique.Footnote39 Whether the gatekeeper be the auditor, the credit rating agency, or someone else, serious reform requires giving investors, as the intended beneficiaries of these services, a greater role in the selection of the gatekeeper. Otherwise, increased competition among auditors could even be counter-productive. For example, increased competition among credit-rating agencies in the years before the 2008 financial crisis produced serious grade inflation, as rating agencies feared the loss of clients if they did not rate debt offerings very favorably (See Coffee Citation2011). Only if the gatekeeper must please investors to remain in office will it loyally serve investors, rather than management.

More generally, sensible reform needs to combine the carrot and the stick. That is, asking the auditor to evaluate the issuer’s internal controls (perhaps annually, perhaps every two years) offers a ‘carrot’: auditing firms increase their revenues (and this justifies increased investment in auditing). Such a change also makes the auditor’s response more observable, giving investors greater ability to judge the differences among auditors. But offering this carrot only makes sense if other changes can encourage shareholders to become involved in the selection of the auditor. A low threshold that would allow 10% of the shareholders to propose an alternative auditor for a shareholder vote would effectively enable one or two activist hedge funds to propose such a replacement. In the U.S., activist funds already are incentivized to undertake corporate governance contests as part of a broader campaign to secure board representation. In the U.K., such contests seem possible (and desirable) if governance rules are simplified. In both countries, proxy advisors (i.e. Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass-Lewis) could play a decisive role, as diversified institutional investors tend to rely on them.

The corresponding ‘stick’ in these proposals would be a tougher grading policy by the FRC, with new sanctions triggered by sustained low grades. Such a balanced policy might combine the following elements:

The end of pass/fail grading and the use of an expanded grading scale with multiple grades that rate the auditor’s performance as excellent, satisfactory, deficient, or failing, with the latter two grades being accompanied by an explanation;Footnote40

Publication of the auditor’s grades on an issuer by issuer basis if the auditor’s performance remained sub-par for a defined period (say, three years);

Mandatory rotation of the auditor for sustained failure (with the same auditor being disqualified for new appointments as a replacement on another’s auditor’s disciplinary rotation);

Increased scrutiny and dialogue between the FRC and the audit committee (with the backstop threat of its replacement as well);

Public reprimand as the minimum sanction if the auditor performs poorly on some number of individual audits; and

A bar on accepting new audit clients (for a defined period) if the firm receives a defined number of low grades.

Tougher grading by the FRC (or any successor agency) should serve not simply as a sanction, but as a catalyst that might lead shareholder activists to propose a new auditor. Unquestionably, such a policy would impose greater costs on issuers and require substantially increased funding for the FRC (and its delegates) to enable them to conduct detailed evaluations of auditors. To justify this greater cost, one can argue that today investors get too little reliable information for the high fees they indirectly incur for audit services. As for increased funding for the FRC, the real issue is whether, even if authorized and instructed to be a tough grader, the FRC would act as one. Grade inflation occurs everywhere, not only in academia. Put even more bluntly, the ‘old boys club’ is a uniquely English institution, and it tends to prefer gentle, private reprimands.

Other elements in a fuller policy of accountability are also necessary and would include:

Requiring large, world class audit firms (both the Big Four and a few others) to accept responsibility for their sibling firms in other jurisdictions. That is, if a Big Four firm audits a hypothetical issuer (Amalgamated Widgets) and relies on the audit of its operations in Italy by its Italian correspondent firm, its overall grade should be affected by that partner firm’s performance; put differently, major firms should not be able (at least for regulatory purposes) to partition themselves into a dozen or more independent firms and accept no responsibility for the failure or underperformance of a sibling firm;

Contingency planning for the failure of a major auditing firm is essential. If a major firm fails (as did Arthur Andersen fifteen years ago), it should not be acceptable for its partners to switch directly to another Big Four firm. That would only give us the Big Three and lessen competition even further. Instead, only smaller firms should be able to hire the refugees from such a failure, and this might cause a smaller firm to grow into a true competitor.

All these steps may seem small, but there is a unifying theme: The auditor of the future must be more than a ‘bean counter,’ but rather should evolve into a watchdog of systemic risk. If the 2008 crisis carries any lesson, it is that such a watchdog is needed – in particular at financial firms.

For the future, the role of the auditor is either going to shrink or expand. It could shrink as the old-fashion bookkeeper becomes increasingly irrelevant as computers gain artificial intelligence. Or it could expand, as the auditor takes on new functions. In this light, asking the auditor of the future to monitor internal controls will, over time, place it in a position of much greater importance where it would sometimes be required to make more discretionary judgments on new and sensitive questions: Is the issuer’s leverage too high to weather a possible crisis? Does the structure of its executive compensation invite executives to take excessive risk? These are questions that need to be evaluated – but not with a pass/fail grade. Rather, a fuller and considered evaluation is needed. Still, to assure accountability, a grading curve needs to be imposed; all auditors cannot receive a grade of A+. Also, the grades would need to be quantified (say on a one to five scale). Such grades would interest investors, permit comparisons among auditors, and encourage recommendations by proxy advisors.

To be sure, some auditors may prefer to avoid such an expanded role and continue to defer to management, but others, motivated in part by a fear of replacement by shareholders, may seek to develop a reputation for independence. To the extent that auditors take on such a role, they could become the critical gatekeeper for the future. But first, we need competition in the selection of auditors to turn a race that today may often be to the bottom into a race to the top.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to acknowledge the research assistance of Roy Cohen and Amy Burr Hutchings, both LLM students at Columbia University Law School.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

† This paper was delivered at the “Better Markets Conference: Financial Scandals: Past, Present and Future” ICAEW, Chartered Accountant’s Hall, Moorgate Place, London EC2R 6EA, December 17-18, 2018.

1. For general assessments, see Bloomberg Editorial (Citation2018) and Plender (Citation2018).

2. See Mellow (Citation2018) (quoting from House of Commons report on Carillion).

3. According to the indictment, PCAOB officials were bribed to advise KPMG as to which of its audits would be reviewed by the PCAOB. The American press has characterized this as ‘stealing the final exam.’ See Armental (Citation2018).

4. See Gryta (Citation2018). The U.S. Department of Justice probe followed G.E.’s announcement of a $22.8 billion quarterly loss following an accounting change.

5. See generally, Shaoib (Citation2017), Doherty (Citation2017), Levring and Wienberg (Citation2018).

6. See Kingman (Citation2018). Unlike the FRC, which is supported by a voluntary levy, the new body, which would be called ‘The Audit, Reporting and Governance Authority’ would directly tax the audit industry for its costs, be accountable to Parliament, and have authority to regulate corporate governance at listed companies. The review of the FRC by Sir John Kingman came after a series of high-profile corporate scandals, which had raised questions about the quality of auditing and the performance of the FRC. For a good overview, see ICAEW Representation (Citation2018).

7. See Competition & Markets Authority, Statutory audit services market study (Update paper 18 December 2018). This study makes two principal recommendations: (1) closer regulatory scrutiny of auditor appointment is necessary by the audit regulator; and (2) audits of large listed companies should be carried out by two firms, ‘at least one of which should be from outside the Big Four.’ Id. at 7. The goal of this joint audit requirement is to develop new competitors who over time could challenge the Big Four. In addition, the CMA also recommended ‘a full structured split of advisory and other non-audit services away from audit.’ Id. at 8. These two divisions – audit and non-audit – could co-exist under the same ‘organizational umbrella,’ but would have ‘separate management, accounts and remuneration.’ Id.

8. See In re Petrobras Sec. Litig. Even though Judge Rakoff cleared PricewaterhouseCoopers of involvement in the fraud, the firm still decided to contribute $50 million to the settlement fund to avoid an appeal and obtain a release. See Class Action Reporter (Citation2018).

9. For overviews of the differences in budget, personnel, and results obtained between the U.S. and the U.K. in the field of securities regulation and enforcement, see Coffee (Citation2007) and Jackson (Citation20Citation0Citation7) on Reg. 213. Even after adjusting for differences in GNP and market size, the U.K.’s investment in enforcement resources is modest in comparison to the U.S.

10. For an overview of this model, see Coffee (Citation2006).

11. In DiLeo v. Ernst & Young, Judge Frank Easterbrook wrote:

An accountant’s greatest asset is his reputation for honesty, followed by his reputation for hard work … It would be irrational for … (accountants) … to join forces with … (fraudulent defendants).

12. For this finding, see Bloomberg Editorial (Citation2018).

13. ‘Agency Costs’ is here used in the standard economic sense as the sum of monitoring and bonding costs plus the irreducible costs of agent disloyalty that are too costly to eliminate. See Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976).

14. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act prohibited accounting firms from providing the following nine consulting services to audit clients: (i) bookkeeping services related to accounting records or financial statements of the client; (ii) financial information systems design and implementation; (iii) appraisal or valuation services; (iv) actuarial services; (v) internal audit outsourcing services; (vi) management or human resources services; (vii) broker-dealer or investment banking services; (viii) legal or expert services related to the audit; and (ix) any other services that the board of the client deemed impermissible. See Section 201 of SOX, which amended Section 10A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78j-1) to add a new section (g). Other non-auditing services were not prohibited but had to be expressly authorized by the corporation’s board.

15. In the EU audit reform of 2014, a major provision was the imposition of a cap on fees for permitted non-auditing services, which was set so that fees for non-audit services could not exceed 70% of the average of the entity’s audit fees over the prior three years. See Regulation No. 537/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Specific Requirements Regarding Statutory Audit of Public-Interest Entities and Repealing Commission Decision 2005/909/EC, 2014 O.J. (L. 158/77) § 4 (EU); see also European Commission Fact Sheet ‘Reform of the EU Statutory Audit Market-Frequently Asked Questions,’ dated 13 June 2016.

16. See Bloomberg Editorial (Citation2018) at p.2.

17. See Bloomberg Editorial at p. 3.

18. See Lisic et al. (Citation2017) at p.30.

19. See Lisic et al. (Citation2017) at p.1.

20. In the U.K., the Big Four audit 97% of the FTSE 350, and each of the 41 FTSE 100 companies that changed auditors since 2013 selected one of the Big Four as the replacement auditor. See Marriage (December Citation2018).

21. Leaked emails showed that KPMG’s South African Office had approved the payment by Linkway Trading of the wedding expenses as a business expense of Linkway Trading. See Skoulding (Citation2018), Cotteril and Marriage (Citation2017).

22. See Motau (Citation2018) at Paragraph 23.9.

23. See Notes 30–33.

24. See www.frc.org.uk/auditors/audit-quality-review/audit-firm-specific-reports. For example, a grade stating ‘limited improvement required’ (which is one of the standard grades) tells investors little. Unless it states what specifically should be improved, it is opaque. For the existing grades, see Note 55.

25. For an overview of the FCA, see ‘The FRC and Its Regulatory Approach' (FRC Publication dated January 2014). See also https://www.frc.org.uk/auditors/professional-oversight/oversight-of-audit/respective-roles-of-government,-the-frc-andthe-ac. The biggest difference is that the FRC was not created by legislation and does not have statutory powers. This seems to be the leading reason that the Kingman Review has suggested that it be replaced.

26. For an overview, see IFIAR, Shaping the Future of Audit Regulation: Annual Report 2017. Among its members in addition to the FRC and PCAOB are the audit regulators of France (Haut Conseil du Commissariat aux Comptes (HBC)), Germany (Auditory Oversight Body (AOB)), Japan (Certified Public Accountants & Auditing Oversight Board/Financial Services Agency (CPAAOB/FSA)), and the Netherlands (Autoriteit Financiale Markten (AFM)).

27. The Statutory Audit Directive (2006/43/EC) was ratified by the EU Parliament and EU Council in 2006 and was required to be implemented by EU member states by June, 2008. Following the 2008 financial crisis, it was further amended in 2014 by Directive 2014/56/EU, which ‘sets the framework for all statutory audits, strengthens public oversight of the audit profession and improves cooperation between competent authorities in the EU.’ See European Commission, ‘Auditing of companies financial statements,’ https://ec.europe.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/auditing-companies-financial-statements_en. Of special relevance to our topic, Article 32 of the Statutory Audit Directive (as amended) requires each Member State to have a competent public authority which has the ultimate authority for the approval and registration of statutory auditors and audit firms and their oversight. Article 32 also permits Member States to delegate or allow their regulatory authority to delegate any of their tasks to other bodies (such as the ICAEW).

28. See ICAEW Representation (Citation2018) at p. 5.

29. On 8 October 2018, the FRC proposed a series of reforms to address the ‘underlying falling trust in business and the effectiveness of audit.’ See https://www.frc.org.uk/news/october-2018/frc-sets-out-new-strategic-focus-to-ensure-audits-s.

30. For the nine prohibited categories of non-audit services, see Note 17. According to the Pakaluk survey, some firms in both the U.S. and the U.K. do pay auditors fees for non-audit services that exceed 70%, and even 100%, of their audit fees, but these are few. See Note 19.

31. See Note 22.

32. See Note 19–20.

33. Contingent fees are allowed (and common) in the U.S., and, although fees may be shifted against one side, if the court finds that it has misbehaved, such fee-shifting is unusual in the U.S., which favors a rule under which each side bears its own legal expenses. See Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society (Citation1975) (explaining the ‘American Rule’ on fees).

34. As of 21 December 2018, a record 284 companies around the world with market capitalizations of more than $500 million were subjected to activist engagements in 2018, up from 252 in all of 2018. 148 of these engagements were of non-U.S. companies. In total, these campaigns won a record 194 board seats for insurgents in 2018 (as of 21 December 2018), which was a 42% increase over 2017. See Lombardo (Citation2018). For a wider-angled overview of their strategy and its impact, see Coffee and Palia (Citation2016). The relevant point here is that hedge fund activists wish to present themselves as the champion of the shareholders, and seeking to replace a long-time and poorly graded auditor would provide them exactly the opportunity they are seeking.

35. For example, in May 2018, the shareholders of SIG plc, a distressed U.K. construction products company whose financial statements and audits had been questioned, declined to re-appoint Deloitte as its auditor. See Kapoor (Citation2018).

36. Section 489 of the Companies Act 2006 says two things about the appointment of the auditor at a public company: First, under Section 489(3), the directors may appoint the auditor at any time before the company’s first accounts meeting and may ‘fill a casual vacancy in the office of auditor.’ Second, under Section 489(4), the members may appoint the auditor by ordinary resolution ‘at an accounts meeting’ or where the directors have failed to make the appointment otherwise. Thus, the company’s articles of association might provide that, absent emergency circumstances, the auditor should be appointed by the shareholders at the accounts meeting.

Under the U.K. Corporate Governance Code (April 2016), which was prepared by the FRC, ‘[t]he audit committee should have primary responsibility for making a recommendation on the appointment, reappointment and removal of the external auditors.’ (Section C. 3.7). Yet, even if the audit committee must make a recommendation, this does not imply that the shareholders or the board must accept their recommendation. Moreover, given that the FRC has adopted the U.K. Corporate Governance Code, it could modify it at least to the point of advising the audit committee to consider seriously any nomination made by a shareholder group (using again a 10% shareholder petition to nominate a candidate).

37. See Note 40 infra.

38. No criticism is here implied of the Kingman Review’s call for a more independent audit regulator with greater powers and guaranteed funding. That is, of course, critical.

39. The position of the credit rating agency is closely analogous to that of the auditor. During the period leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, promoters and underwriters seeking to sell risky debt securitizations of residential mortgages to investors could play the then three principal credit rating agencies off against each other in order to obtain inflated ratings from them. Although the position of the auditor is different in important respects, the Big Four constitute a similar oligopoly.

40. I understand that the existing grading system rates auditors as (i) good, (ii) limited improvement required, (iii) improvement required, and (iv) significant improvement required. This is less than ideal and clearly needs a supplemental explanation.

References

- Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975).

- Armental, M., 2018. Former PCAOB Inspections Leader, KPMG Executives Pleads Guilty. Dow Jones Institutional News. [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Bloomberg Editorial, 2018. Maybe the Big Four Auditing Firms Do Need to Be Broken Up. Bloomberg. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-06-18/maybe-the-big-four-auditing-firms-do-need-breaking-up [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Carillion Report, 2018. House of Commons _ Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy & Work and Pensions Committees, Carillion: Second Joint Report form the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and Work and Pension Committees of Session 2017–19 at p. 79. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm 2017-19/cmselest/cmworpen/769/764.pd/ [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Class Action Reporter, 2018. PricewaterhouseCoopers: Pomerantz Recovery Reaches $3 Billion. Class Action Reporter, March 23, 2018. Available from: http://bankrupt.com/CAR_Public/180216.mbx [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Collinson, P., 2018. Accounting Watchdog Could Ban Auditors from Consultancy Work. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/oct/08/accounting-auditors-consulting-frc-kpmg [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Coffee, J., 2006. Gatekeepers: The Professions and Corporate Governance at pp. 2–3.

- Coffee, J., 2007. Law and the market: the impact of enforcement. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 156, 229.

- Coffee, J., 2011. Ratings reform: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Harvard Business Law Review, 1, 231.

- Coffee, J. and Palia, D., 2016. The wolf at the door: the impact of hedge fund activism on corporate governance. The Journal of Corporation Law, 41, 545.

- Cotteril, J. and Marriage, M., 2017. South Africa Businesses Under Pressure to Cut KPMG Ties. Financial Times. Available from: https://on.ft.com/2CJk5Wp [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- DiLeo v. Ernst & Young, 901 F. 2d 624, 629 (7th Cir. 1990).

- Doherty, R., 2017. KPMG’s South Africa’s Leadership Resigns Over Gupta Scandal. ECONOMIA. September 15, 2017. Available from: https://economia.icaew.com/en/news/september-2017/kpmg-south-africa-leadership-resigns-over-gupta-scandal. [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- Equilar, 2016. 2015 CEO Pay Strategies at p. 90.

- Frydman, C. and Jenter, D., 2010. CEO compensation. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 2, 75–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-financial-120209-133958

- Gryta, T., 2018. G.E. Slashes Dividend, Discloses Criminal Probe; Shares Sink. The Wall Street Journal Online. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/general-electric-slashes-quarterly-dividend-to-1-cent-1540896132 [Accessed 31 December 2018].

- ICAEW Representation 92/18, 2018. Review of the Financial Reporting Council by Sir John Kingman: ICAEW Submission.

- In re Petrobras Sec. Litig., 317 F.Supp. 2d 858 (S.D.N.Y. 2018).

- Jackson, H.E., 2007. Variations in the intensity of financial regulation: preliminary evidence and potential implications. Yale Journal on Regulation, 24, 253–290.