https://peoplepill.com/people/wilhelm-reich/

The strategic adversary is fascism … the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us. It's too easy to be antifascist on the molar level, and not even see the fascist inside you, the fascist you yourself sustain and nourish and cherish with molecules both personal and collective. —Michael Foucault, Preface to the English edition, Anti-Oedipus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Citation1983 [1972]. Translated from the French by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota, p. xiil

Introduction

The first two decades of the twenty-first century has been accompanied by the ‘return’ of fascist behavior and the cultivation of Fascist philosophy in the troubled liberal democracies of the West. We have also witnessed the consolidation of authoritarian one-party States in Russia, China, the Middle East, Asia and Africa, producing some non-traditional alliances across the East-West and North-South divides.Footnote1 Political theorists make various distinctions between totalitarianism, authoritarianism and fascism to advance both historical analysis and connections between civil society and authoritarianism.Footnote2 While they are all forms of government they differ in term of the power of the state, the cult and charisma of the leader, the limits of political freedom, the celebration of violence and in terms of the concept of desire. Fascistic sexuality based on domination and sex-authoritarianism in a ‘masculinist culture’ is fundamentally anti-women believing in general that women should be at home having and looking after babies. Increasingly, illiberal elements have appeared in democracies with the rise of anti-immigration, anti-environmentalist, racist and white supremacist parties and movements, as well as the rise and consolidation of various darknet terrorist networks across Europe, Latin American and the US.

In Europe the need to resurrect national identities that reflect the assertion of ‘pure’ ethnic and religious affiliations have accentuated strong nationalistic sentiments with an emphasis of concepts of sovereignty and territoriality as well as the appeal to racist ideas of ‘pure blood’ and ‘whiteness’. The rise of neofascist parties in Europe is often seen as a consequence of the mass ‘refugee problem’ of immigrants in Syria, Libya and North African states who are fleeing war or conflict, often instigated by the US and allies. Fascist parties in Germany, France, Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Poland, Italy, Greece, Spain and other European countries have become extremely xenophobic insisting on limits to immigration and increased militarized borders (Peters & Besley, Citation2015).

The scholarly press is awash with reports of the ‘rise’ or ‘return’ of Fascism which is normally taken to be a specific historical period between the years 1919-1945, especially in Germany, Spain, and Italy. Many commentators emphasize the continuity with historical Fascism and focus on racism, eugenics, and white supremacy, based on the biopolitical paradigm of the ‘camp’ and policies for the extermination of Jewish and other groups including Roma people, communists, ‘homosexuals’ (LGBTQ), and the mentally ill, all of whom were classified as non-citizen and non-human in the eyes of the state (Agamben, Citation2000; Peters, Citation2018).

A study of the social pathology of neo-fascism in the twenty first century has given rise to a novel form of ‘radical right-wing populism’ characterized by ‘nativism (i.e., a combination of nationalism with xenophobia), authoritarianism (law and order issues), and populism (a populist critique of liberal democracy rather than outright anti-systemic opposition)’ (Copsey, Citation2013). The post-1980 ‘third wave’ was highly policized and dominated by emotional left-wing analysis. As Copsey (Citation2013) explains:

Instead of viewing radical-right populism as a ‘normal pathology’ of liberal democracies - a pathology that is alien to democratic values and which, under normal conditions, is ever present but struggles to spread throughout the body politic - Cas Mudde contends that radical right-wing populism is best interpreted as pathologically normal, that is to say, both entirely unremarkable and whilst not necessarily part of the mainstream, is connected to it nonetheless. https://brill.com/view/journals/fasc/2/1/article-p1_1.xml?language=en

Copsey (Citation2018) wants to challenge the distinction between the ‘radical right’ and ‘fascism’ made by contemporary studies to suggest that ‘(neo)fascism’s past offers the best route to understanding the present-day radical right.’ In these terms education is best seen as challenging youth racism and the formation of far-right attitudes (Copsey, Citation2018; Copsey, Temple, & Carter, Citation2019).

Some scholars argue that this rise is a consequence of the failure of liberal citizenship to address historical oppression and to deliver on the promise of inclusion and the expansion of rights of citizenship as part of the emancipatory intent of the Enlightenment project (e.g., Tamás, Citation2000). Others see and the rise of White Nationalist and ‘Alt-right’ as a reaction to foreign policies pursued by the US and the West in a series of wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syrian and the provocation of Iran that has caused the largest historical migration of displaced people into Europe (Bergman & Mazetti, Citation2019; Hinnebusch, Citation2007). For some Marxist theorists Fascism is a stage of capitalism precipitating an economic crisis that develops out of the decay of liberal institutions (Amin, Citation2014; Suvin, Citation2017). Each of these perspectives impinge on the question of citizenship and citizenship rights, although Suvin (Citation2017) also depicts fascism as a mass social pathology under capitalism. In this essay I want to follow a line of argument that puts the emphasis less on specific historical conditions and focuses instead on the psychology of fascism, in an argument first developed and explored by the much-maligned figure of Wilhelm Reich, whose work has been picked up in different ways by Eric Fromm, Michael Foucault and Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Evans and Reid (Citation2013) provide the general gloss on retheorising fascism and its relations with liberalism:

The problem of fascism today cannot simply be addressed as that of the potential or variable return and reconstitution of fascism, as if fascism had ever, or could ever, ‘disappear’, only to return and be made again, like some spectral figure from the past. The problem of fascism cannot, we believe, be represented or understood as that of an historically constituted regime, particular system of power relations, or incipient ideology. Fascism, we believe, is as diffuse as the phenomenon of power itself. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203374702/chapters/10.4324/9780203374702-6

Neofascism defines the new age of politics after the decline of liberal internationalism. I do not hold to the thesis about the inevitable decay of liberal institutions under capitalism but do emphasise a culpability of liberalism in dealing with problems of citizenship that in part spring from its complicity with neoliberalism at the level of philosophical assumptions. This is clearly visible in the way in which the universities have been ‘corrupted’ and systematically closed down as institutions designed to protect liberal freedoms. By focusing on profit and grants at the expense of academic freedom by utilising public choice apparatus and policies universities have been turned into businesses with a corporate identity and voice, unable to intervene in social and political debates, especially when profits or reputation are at stake.

Reich and the psychology of fascism

Wilhelm Reich, the dissident Freudo-Marxist Viennese psychiatrist, colleague of Freud and erstwhile member of the Frankfurt School, published The Mass Psychology of Fascism in 1933 with the aim of explaining why Germany turned towards Fascism rather than Communism in the period 1928-1933. He reasoned that one of the main factors was that the working class chose Fascism principally because of increased sexual repression which was basis of repressed sexual energy turned toward authoritarianism. This was in marked contrast to the relative sexual liberation of revolutionary Russia. He was at pains to explain a central conundrum:

What was it that caused [the masses] to follow a party the aims of which were, objectively and subjectively, strictly at variance with their own interests? (Reich, Citation1946 [1933], p. 34).

Why do people seek their own repression under authoritarian regimes when it is clearly against their own self and class interests? Why do people crave an authoritarian figure, a transcendent authority behind which they can mask their repression of all-powerful biological impulses that percolate through to the rational mind often accompanied by violent outbursts? The ideology of Germany at the time was an ‘affective ideology’ anchored in emotions rather than argument.

Reich joined the communist Party in 1928 and visited Russia in 1929, studying nurseries and schools. In The Sexual Revolution he praised the undermining of the bourgeois patriarchal family through the process of collectivization and warned against the banning of homosexuality. He was one of the first to examine the social pathology of fascism as a psychological condition that adopted a Freudo-Marxist approach:

In 1932, on the eve of Hitler’s triumph in Germany, he worked with Erich Fromm, Karl Landauer, the director of the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute and Heinrich Meng at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, the beginning of the merging of Marxism and Psychoanalysis. [corrected]

Reich saw sexual repression in society as the origin of psychological repression in the mind of an individual. Thus Reich urged a sexual revolution and greater sexual freedom in order to reduce the prevalence of neuroses, and facilitate the development of a more healthy political life. https://www.marxists.org/glossary/people/r/e.htm#reich-wilhelm

In his approach to the psychology of Fascism he used an approach he call Sex Pol that related the economic to the psychological to argue that the nexus was the authoritarian family that embodied the structures and ideologies of the authoritarian state. As he put it:

Suppression of the natural sexuality of the child, particularly of its genital sexuality, makes the child apprehensive, shy, obedient, afraid of authority, “good” and “adjusted” in the authoritarian sense; it paralyzes the rebellious forces because any rebellion is laden with anxiety; it produces, by inhibiting sexual curiosity and sexual thinking in the child, a general inhibition of thinking and of critical faculties. In brief, the goal of sexual suppression is that of producing an individual who is adjusted to the authoritarian order and who will submit to it in spite of all misery and degradation. At first, the child has to adjust to the structure of the authoritarian miniature state, the family; this makes it capable of later subordination to the general authoritarian system. The formation of the authoritarian structure takes place through the anchoring of sexual inhibition and sexual anxiety (Reich, Citation1946 [1933], pp. 25–26).

Fascism is thus not simply an ideology in the sense of being part of a cognitive schema; it is anchored in the body, in desire and the emotions. Reich argued that suppression of natural genital child sexuality can produced malformed political subjects with a sense of powerlessness and aggression, who is always looking for a father figure on the analogy of the patriarchal family.

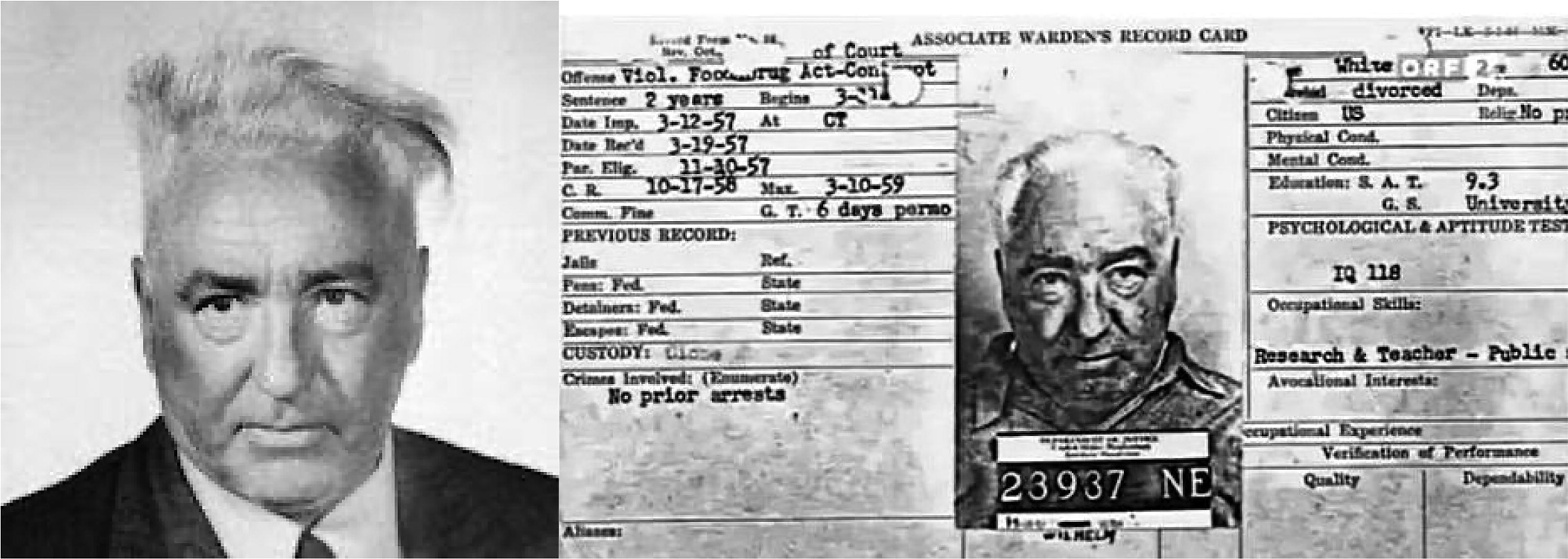

Reich biologizes sex and desire and ties fascism to the patriarchal structure of the family. His views not unsurprisingly were seen as suspect from the start. He was expelled from the German Communist Party and later the International Psychoanalytic Association. His books were burned by the Nazis and later after emigrating to the US his work came under attack and under a judge’s orders his books and other apparatus were destroyed. He was imprisoned in 1957 at Danbury Federal Prison and later Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary where his mental health was examined. He later died the same year in Lewisburg.

Fromm’s humanism, alienation and freedom

Eric Fromm, a German-escapee Jew who fled to New York when the Nazis came to power was a prominent social psychologist and philosopher associated with the Frankfurt. He published Escape from Freedom in 1941 that later became known in Britain as Fear of Freedom (1942). It was one of the foundation texts of political psychology. He was interested to explore the psychological conditions that gave rise to the Nazi regime. Fromm distinguished between negative freedom (freedom from) and position freedom (freedom to) where the former referred to freedom from state and social conventions and the former, a mark of authenticity, that laid the basis for an integrated personality through creative acts. The latter requires the overcoming of feelings of hopelessness and struggling to free oneself from authority but personal authenticity often is not achieved and gives way to replacement of the old system by submitting to a new authoritarian system. He begins The Fear of Freedom (1942) with ‘Talmudic Saying Mishnah, Abot’: ‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am for myself only, what am I? If not now– when?’ In the Preface he goes on to lay out his argument:

It is the thesis of this book that modern man, freed from the bonds of preindividualistic society, which simultaneously gave him security and limited him, has not gained freedom in the positive sense of the realization of his individual self; that is, the expression of his intellectual, emotional and sensuous potentialities. Freedom, though it has brought him independence and rationality, has made him isolated and, thereby, anxious and powerless. This isolation is unbearable and the alternatives he is confronted with are either to escape from the burden of this freedom into new dependencies and submission, or to advance to the full realization of positive freedom which is based upon the uniqueness and individuality of man (p. ix) https://pescanik.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/erich-fromm-the-fear-of-freedom-escape-from-freedom.pdf

The task he sets himself is to understand ‘the reasons for the totalitarian flight from freedom’. He sought to understand why millions in Nazi Germany sought ways of escaping freedom: ‘eager to surrender their freedom’, ‘instead of wanting freedom, they sought for ways of escape from it’ (p. 3). And he quotes Dewey (Citation1940) to good effect:

The serious threat to our democracy … is not the existence of foreign totalitarian states. It is the existence within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions of conditions which have given a victory to external authority, discipline, uniformity and dependence upon The Leader in foreign countries. The battlefield is also accordingly here– within ourselves and our institutions (p. 3) [Freedom and Culture).

It is worth referring to Fromm’s questions that he sets himself:

These are the outstanding questions that arise when we look at the human aspect of freedom, the longing for submission, and the lust for power: What is freedom as a human experience? Is the desire for freedom something inherent in human nature? Is it an identical experience regardless of what kind of culture a person lives in, or is it something different according to the degree of individualism reached in a particular society? Is freedom only the absence of external pressure or is it also the presence of something–and if so, of what? What are the social and economic factors in society that make for the striving for freedom? Can freedom become a burden, too heavy for man to bear, something he tries to escape from? Why then is it that freedom is for many a cherished goal and for others a threat? (p. 4)

Fromm (Citation1947) further developed his humanist theory of alienation in Man for Himself by distinguishing ‘character orientations – one ‘productive’ and four ‘non-productive’: receptive, exploitative, hoarding, and marketing. These ideas became the basis for his The Sane Society (1955) and his highly successful The Art of Loving (1956) that completes his theory of human nature by arguing that love is a skill that can be taught and developed.

Foucault’ ‘introduction to a non-fascist life’: bio-power and neoliberalism

In the Preface to Anti-Oedipus (Deleuze & Guattari Citation1983), Foucault observes that fascism is already in ‘everyday behavior’; it is ‘the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us’ (Foucault, Citation1983, p. xiii). The Rosa Luxemberg Stiftung (RLS) (Citation2017) express the essence of Foucault’s approach

Ever since the rise of Italian fascism and German Nazism in the first part of 20th Century and up till today the term fascism comprised the terminological core of left-wing (especially socialist) theoretical and political projects…

Michel Foucault’s discovery in the 1960s of “everyday life fascism” is a symptomatic example. Foucault’s reconceptualization of fascism strove to shift the analytical focus from big political personalities, parties, movements and regimes of the early 20th Century towards the “tyrannical bitterness” of our minds, and actions that endow us with the lust for power and domination. https://www.rosalux.rs/en/how-do-we-think-about-fascism-today

Yet RLS also argue that Foucault’s reconceptualization also suffers from the abstract nature and level of generality of the concept that does not provide enough discrimination among mechanism of power relations.

Foucault investigated the resurgence of Fascism in terms of the political framework of bio-power demonstrating interesting and useful conceptual links

between the bio-politics of neoliberalism and the extreme bio-politics of Nazism/Fascism, where many disabled, and mentally ill people, or just those labelled as “antisocial” were described as economically bad investments and termed Unnütze Esser (useless eaters), or simply Lebensunwertes Lebens (life unworthy of life)….

In Foucault’s works Fascism had its origins in bio-politics and ideas from psychiatric history such as eugenics and degeneration theory, which justified state racism and extreme violence in order to maintain a certain “social body.” (York, Citation2018).

Deleuze and Guattari, and the social production of fascist desire

Holland (Citation1987) provides a clear analysis of ‘Introduction to the Non-Fascist Life’ through Deleuze and Guattari’s (Citation1983 [1972]) Anti-Oedipus emphasising that while the work was addressed to the way fascism manifests itself in our behaviour and how we can thus deal to it, the work was directed toward ‘both the radical nature of the new student and worker demands and the reactionary nature of the opposition voiced by the Communist Party and other supposedly “radical” institutions.’ He goes on to note that Anti-Oedipus for Foucault was not a ‘grand synthesis’ but that Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘materialist psychiatry’ does emerge as an intersection among the three great materialisms of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud.

parts of the Freudian conceptual apparatus are retained, but are then grafted onto a historical perspective derived in part from the Marxian notion of modes of production; the basic value system of schizoanalysis, finally, is grounded in a Nietzschean critique of consciousness and celebration of unconscious will-to-power. The lines of interference among these materialisms meet in a notion of general semiosis that includes the investment of energy in all domains of human endeavor, from the production of value in a factory, for example, to the production of consensus in a political formation, to the production of meaning in a work of art.

The concept of desire enables Deleuze and Guattari to production as an investment of human energy that produces social reality, ‘both in the economic sense of labor-power shaping the material world and in the cognitive sense of psychic drives shaping the phenomenal world’… and ‘libidinal and social production are for schizoanalysis simply two domains of application of the same general semiosis.’ As York (Citation2018) puts it ‘Deleuze and Guattari suggest that their theory of materialist psychiatry has two goals: introducing desire into the social realm and introducing production or economy into desire.’ As she notes Fascism for Deleuze and Guattari ‘is something that ‘develops out of ingrained behaviour, relationships, and patterns of thought, which stem from structures of domination, control, and exploitation.’ It is a latent force that operates within neoliberal global capitalism that thrives on the free flow of goods even at a time when borders have become the basis for greater territoriality and militarized borders that divide the population along racist lines to affirm the menace of white-only and other forms of ethnic nationalism.

Educational approaches to the non-fascist life

Many political commentators have noted the rise of 21st century Fascism. Adele M. Stan (Citation2018) describes Trump as a Neo-Fascist. umair haque (Citation2018) usefully extends the notion to the Islamic world as ‘theofascism’ and speaks of American proto-fascism as ‘a clear derivative of centuries of supremacy, slavery, and segregation.’ Others talk of ‘Why 21st Century Fascism is Inevitable’ or the rising threat of fascism.Footnote3 Steve Bynum (Citation2019) describes

‘What Fascism Looks Like in the 21st Century’ through an interview with Jason Stanley, who explains in his new book Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them that fascist roots are part of a ‘Us and Them’ ideology that has been ‘present in American politics for at least the last hundred years’.Footnote4 Contemporary American politics does set trend within the West and it’s not just the contagion effect. People like Steve Bannon has been actively supporting Far-right politics in Europe for some time. Clearly much rides on the coming US elections and whether the join forces of the Democratic Left can achieve solidarity, reinvent itself in a more populist way, and repair the damage that trump has caused to democracy and the democratic way of life.

For me this takes precedence as the primary goal for philosophy of education in a new key – one that aims to address the question of how we can pursue a non-fascist life. In this Natasha Lennard’s (Citation2019) Being Numerous: Essays on Non-Fascist Life provides a sophisticate analysis, that, perhaps surprisingly, draws on Wittgenstein and Eco’s use of ‘family resemblance’ to address questions of meaning. She provides a mash-up of ‘We Anti-Fascists’ the first chapter of her book. She intones: ‘Liberal appeals to truth will not break through a fascist epistemology of power and domination’. Lennard talks of ‘fascistic habit formed of fascistic desire to dominate, oppress and obliterate the nameable other’.Footnote5

As a philosophy of education it comes to try to understand how we become fascist and exhibit fascistic behaviour in the neoliberal mode where we can at once espouse humanist ideals and anti-neoliberal rhetoric in our writing but then as neoliberal managers engage in fascistic habits in our work environments. For my part I do believe that we need a closer understanding of the institutional and family conditions of microfascism but this understanding also requires a detailed investigation of the current and emerging institutions, politics and historical changes accompanying the rise of fascism. As psychiatry was exploited as a weapon of fascism (Abbott, Citation2016; Piazzi, Testa, Del Missier, Dario, & Stocco, Citation2011), so anti-psychiatry can be a good starting point to unthread fascism as a society-level mental disorder, a repudiation of democracy, and a form of social pathology of politics that turns on Reich’s observation that people desire their own oppression in authoritarian regimes. In the epoch of digital reason where bullying is a normalised part of (un)social media, fascistic habits are formed and consolidated.Footnote6 If social democracy is to be ‘saved’ it needs to be reinvented as a critique of capitalism and its abuses of power. We need also to return to Reich’s insight of linking sexuality, desire and fascism. There is a strong link between sex and violence as a sado-masochism concept of fascist desire as that which desires its own domination and oppression manifest in gaining pleasure from acts or the infliction of pain and humiliation. In sexual acts it desires its own repression through totalitarian emotions. Deleuze and Guattari (1972) write in A Thousand Plateaus:

only microfascism provides an answer to the global question: Why does desire desire its own repression, how can it desire its own repression? …

The question demands both and historical and psychological explanation, especially given the way in which authoritarianism has grown profusely and in different ways in the troubled democracies of the west but also in terms of the rise of one-party states. In their ‘Introduction: fascism in all its forms’ to Deleuze & Fascism: Security, War, Aesthetics Evans and Reid (Citation2013) write: ‘The post-war Liberal imaginary is predicated on the doubly political and moral claim to have somehow overcome fascism’.Footnote7 But overcoming fascism is not just a matter of politics and morality it is a depth psychology that requires the cultivation of the liberal (open) as opposed to the authoritarian (closed) personality. The social pathology of fascism in the twenty first century requires a social antidote to sadism and masochism and why and how people gain pleasure from the misery of others. The rapid growth of violent hate groups, the rise of fundamentalist and exclusionary religious groups both Christian and Islamic, the extreme violence against immigrants and refugees, the social pathologies associated with white supremacism, and the systematic sexual oppression of women require immediate and ongoing attention.Footnote8 Ultimately, the growth of forms of neofascism and its philosophical defence in terms of the appropriation of Nietzsche’s works needs the most robust philosophical analysis.Footnote9

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See the list of authoritarian regimes at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authoritarianism

2 See Finchelstein (Citation2019) for an analysis of the relations between fascism and populism; Riemen (Citation2018) who explores the theoretical weakness of fascism and the spiritual crisis of our age in term of European humanism; Riley (Citation2010) who explores the connection between civil society and authoritarianism in Italy, Spain and Romania; Hett (Citation2018) who investigates how the Nazi party came to power; and Albright (Citation2018) who issues a warning about fascism and the erosion of democracy.

3 https://medium.com/why-21st-century-fascism-is-inevitable; https://socialism.com/fs-article/the-rising-threat-of-21st-century-fascism/

6 Jojo Rabbit (2019) is a movie comedy written and directed by Taika Waititi, based on Christine Leunens's book Caging Skies, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tL4McUzXfFI, that deals brilliantly with some of these themes.

8 I have benefitted from Rowan Tepper’s ‘In The Time of Fascist Desire’, https://www.academia.edu/228788/In_The_Time_of_Fascist_Desire

9 See by comparison, Babich (Citation2019) and Beiner (Citation2018).

References

- Abbott, K. (2016). Psychiatry as a weapon of fascism: How psychiatry was systematically exploited to advance the ideological objectives of the Nazi regime. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/selcs/sites/selcs/files/travel_essay_3.pdf

- Agamben, G. (2000). What is a camp? In Means without end: Notes on politics (V. Binetti & C. Casarino, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Albright, M. (2018). Fascism: A warning. New York, NY: Harper.

- Amin, S. (2014). The return of fascism in contemporary capitalism, Monthly Review. Retrieved from https://monthlyreview.org/2014/09/01/the-return-of-fascism-in-contemporary-capitalism/?v=6cc98ba2045f

- Babich, B. (2019). Nietzsche (as) educator. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(9), 871–885. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1544455

- Beiner, R. (2018). Dangerous minds: Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the return of the far right. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bergman, R., & Mazetti, M. (2019). The secret history of the push to strike Iran. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/magazine/iran-strike-israel-america.html

- Copsey, N. (2013). ‘Fascism … but with an open mind.’ Reflections on the Contemporary Far Right in (Western) Europe. Fascism, 2, 1–17.

- Copsey, N. (2018). The radical right and fascism. In J. Rydgren (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the radical right. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.6

- Copsey, N., Temple, D., & Carter, A. (2019). Challenging youth racism: Project report. Teesside University.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983 [1972]) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (R. Hurley, M. Seem, & H. R. Lane, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987, [1980]). A thousand plateaus. (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dewey, J. (1940). Freedom and culture. New York, NY: Putnam.

- Evans, B., & Reid, J. (2013) Introduction: fascism in all its forms, Deleuze & Fascism: Security: War: Aesthetics. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Foucault. (1983). Preface. Retrieved from https://libcom.org/files/Anti-Oedipus.pdf

- Finchelstein, F. (2019). From fascism to populism in history. University of California Press.

- Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. New York, NY: Farrar & Rhinehart. Fear of Freedom (1942) UK. Retrieved from https://pescanik.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/erich-fromm-the-fear-of-freedom-escape-from-freedom.pdf

- Fromm, E. (1947). Man for himself, an inquiry into the psychology of ethics. New York, NY: Rhinehart.

- Fromm, E. (1955). The sane society. New York, NY: Rhinehart.

- Fromm, E. (1956). The art of loving. New York, NY: Harper.

- Hett, B. C. (2018). The death of democracy: Hitler’s rise to power. New York, NY: Holt.

- Hinnebusch, R. (2007). The US invasion of Iraq: Explanations and implications. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 16(3), 209–228. doi:10.1080/10669920701616443

- Holland, E. W. (1987). “Introduction to the non-fascist life”: Deleuze and Guattari’s “Revolutionary” semiotics. L’Esprit Créateur, 27(2), 19–29. doi:10.1353/esp.1987.0048

- Lennard, N. (2019). Being numerous: Essays on non-fascist life. London: Verso

- Peters, M. A. (2018). The refugee camp as the biopolitical paradigm of the west. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(13), 1165–1168. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1379753

- Peters, M. A., & Besley, T. (2015). The refugee crisis and the right to political asylum. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(13-14), 1367–1374. doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1100903

- Piazzi, A., Testa, L., Del Missier, G., Dario, M., & Stocco, E. (2011). The history of Italian psychiatry during fascism. History of Psychiatry, 22(3), 251–267. doi:10.1177/0957154X10378270

- Reich, W. (1946 [1933]). The mass psychology of fascism. New York, NY: Orgone Institute Press.

- Riemen, R. (2018). To fight against this age: On fascism and humanism. New York, NY: Norton.

- Riley, D. (2010). The civic foundations of fascism in Europe: Italy, Spain, and Romania, 1870-1945. London: Verso.

- Rosa Luxemberg Stiftung (RLS). (2017). How do we think about fascism today? Retrieved from https://www.rosalux.rs/en/how-do-we-thinkabout-fascism-today

- Stan, A. M. (2018). Trump and the rise of 21st century fascism, The American Prospect. Retrieved from https://prospect.org/power/trump-rise-21st-century-fascism/

- Steve, B. (2019). What fascism looks like in the 21st century. Retrieved from https://www.wbez.org/shows/worldview/what-fascism-looks-like-in-the-21st-century/f4771081-ddfc-45d9-b9cf-e61b1e6b2c6f

- Suvin, D. R. (2017). To explain fascism today. Critique, 45(3), 259–302. doi:10.1080/03017605.2017.1339961

- Tamás, G. M. (2000). On post-fascism: The degradation of universal citizenship, Boston Review. Retrieved from http://bostonreview.net/world/g-m-tamas-post-fascism

- umair haque. (2018). The (new) fascisms of the 21st century: Why fascism’s spreading to every corner of the globe, and how it differs from last time. Retrieved from https://eand.co/the-new-fascisms-of-the-21st-century-2c1a3ce3b45e

- York, E. D. (2018). Disorder: Contemporary fascism and the crisis in mental health (A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts, the Department of Political Studies). University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.