Abstract

The global pandemic has pushed many of us to online streaming services. A particular genre in these services is the ‘end of the world’ science fiction film, in and through which the speculated results of processes such as climate change are depicted. CGI technology is frequently deployed to create images of the end of the world, which is a backdrop to the narrative of, ‘saving ourselves amidst the ruins’. This philosophy of education essay will critically examine ten films in order to:

Explain how ‘the end of the world’ images connected to processes such as climate change, obscures and displaces attention from the real, scientifically proven processes that are not so entertaining, but are still deadly. The images are created by capital and its machines for audience attention and have little to do with real social change. Science sits in an ambiguous position in this paper in that the real processes of climate change proven by science may be funded by capitalist mechanisms that can also be their cause.

Introduce a reformulated notion of ecosophy from the work of Félix Guattari, Murray Bookchin, Arne Næss and Andre Gorz. This essay will suggest that ecosophy has the potential to teach the underlying split between depictions of the end of the world through the capitalist machine and the real social change necessary under climate change. Ecosophy is in the context of this essay a specific conceptual construction designed for teaching about climate change through cinema.

Introduction

Everyone, deep in their hearts, is waiting for the end of the world to come.

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84

This philosophy of education article argues that 1960s and 1970s anti-establishment counter narratives to the western mainstream can be revived and taught as a strategic educational response to the threat of climate change (e.g., Chaplin & Mooney, Citation2017). The renaming of this epoch as the Anthropocene from the conditions of the benign Holocene (Dryzek & Pickering, Citation2018), and the underlying realization that humans are causing the onset of the sixth great extinction event (Steffen et al., Citation2011), present overwhelming reasons to rethink education, pedagogy and curriculum in favour of methods, content and assessment that genuinely moves society onto a path to deal with the prospect of catastrophic climate change. Yet one might legitimately ask: Why look to revive 1960s and 1970s counter narratives to the mainstream, as they seem to have failed, in the light of overwhelming, mainstream capitalist pressure? The answer to this question is that even though it is true that the western capitalist mainstream has outmanoeuvred, tamed, and nullified any opposition to its societal and world domination, the 1960s and 1970s counter narratives to the western mainstream hold the secret to their dissolution, as they work from within. In contrast to, for example, the dialectic and frequently oppositional stance of anti-capitalism (Bonefeld & Tischler, Citation2002), the 1960s and 1970s narratives, congealed and focused here in terms of climate change education as ‘ecosophy’; does not attempt to set up a rational dialogue with contemporary capitalism, but sets out to subvert it from within, and in order to deal with dangerous climate change through education.

The method for teaching about climate change as ecosophy that has been chosen for this article is the analysis of the images of ten films (See below). Cinema is used for this philosophy of education piece, as it is the unconscious that explains how ecosophy works from within to subvert the western mainstream (Mickey, Citation2014). However, this is not a psychoanalytic approach to teaching and learning about climate change (Weintrobe, Citation2013). Rather, the unconscious that is analysed through the ten films below is fully mobile, and not contained by or repressed by an ego, super-ego or subjectivity, but able to move fluidly in and through society (cf., Bowie, Citation1993). This is a deliberate move to connect the analysis of film with climate change not as a representational means to understand how climate change and the end of the world might look, but to work on two axes that are crucial to the reformed education that is proposed by the article: 1) As a means to understand time and climate change through the modes in which ‘the end of the world’ are depicted in cinema; 2) As an ecosophical approach to comprehend society at the end of the world, and especially through the unconscious forces that are apparent in and through the analyses of the films. In sum, this article works on these two axes to reinvigorate 1960s and 1970s critiques of the mainstream, not as a facile gesture to what was once radical, or to reinvent a long dead revolutionary praxis (e.g., Bishop, Citation2012), but to genuinely engage with climate change education as a means to subvert societal mores, and as a pedagogic change agenda that could work.

Table 1. Ten films that depict ‘the end of the world’.

What is ecosophy?

The term ‘ecosophy’ emerges in the 1970s from the work of Félix Guattari (Citation2000) and Arne Naess (Citation1990). The term literally means ecology + philosophy, though has a different focus and direction in the systems of thought of Guattari and Naess. For Guattari, ecosophy is aligned with his anti-psychiatrist project that stemmed from his treatment of patients at La Borde institute in France, and his philosophical ideas on capitalism and schizophrenia with Gilles Deleuze (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1984, Citation1988). For Guattari, ecosophy is intimately connected to his notion of social ecology (and mental ecology), that he developed in unison, to enable new thought on environmental matters that does not remain isolated and separate from social and existential contentions (Guattari, Citation2000). In effect, Guattari believed that thinking about the environment, and acting on environmental matters cannot be separated from thinking and acting on social and mental concerns, a conceptual framing that he sets out in his three ecologies (Ibid.). The position of ecosophy from Guattari (Citation2000) was influenced by his dual work with Gilles Deleuze (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1984, Citation1988), even though these works do not mention ecology, 1000 Plateaus was based on Bateson’s (Citation2000) ecology of the mind. In 1000 Plateaus, ecosophy is resolved as the construction of dated plateaux, that are conjoined intensities on ‘planes of immanence’. In effect, 1000 Plateaus is a guide to doing ecosophy, as it presents a method of conceptual ecology (Cole & Mirzaei Rafe, Citation2017) that can be built around phenomena such as teaching ecosophy through cinema. Further, the cinematic aspect of this paper, and its connection to ecosophy can be related to Deleuze’s (Citation1989, Citation1992) cinema books. The thesis of these books is that post-war cinema has progressively developed the ‘time-image’, that examines time itself, and that the images of cinema think, separate from human consciousness. As such, the time-image and images that think add to Guattari’s (Citation2000) ecosophy, in that they present a medium and focus for performing its tenets.

In contrast, Naess (Citation1990), who also founded the ‘deep ecology’ movement, and whose principles helped to define the early Green parties, worked on an ecological agenda, as an immersion in and with nature, that sought to enable ecological thinking in the mainstream, and to provide a practical and effective guide to rethinking human environmental effects. Whilst the deep ecology movement has spawned some extreme reactions in terms of, for example, eco-terrorists (Vanderheiden, Citation2005), who have chosen to take violent action against the socio-economic-industrial complex; Naess’s (Citation1990) view on ecosophy has been successful in helping to develop a rational, normative and stable position from which to critique the negative environmental effects of capitalism (e.g., through Green political parties). It is important to include the deep ecology from Naess as its immersive and widely accepted practice helps to raise consciousness with respect to environmental matters and how to respond to them (Cole, Citation2021). However, it is also true that neither Guattari’s nor Naess’s positions on ecosophy has been wholly successful in inducing the widespread ecological thinking that they set out to achieve, and this is one of the reasons they are combined in this article with the thought of social ecology from Murray Bookchin (Citation2006) and the degrowth that was first mentioned by André Gorz (Kallis et al., Citation2014) because social ecology and degrowth strengthen the position of ecosophy with respect to society and economics.

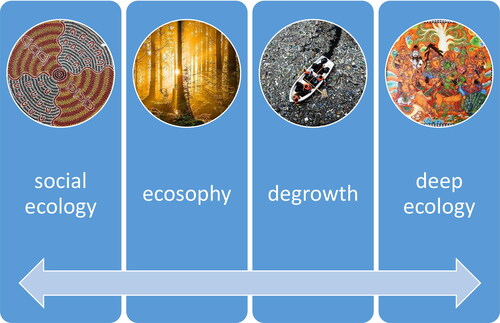

Bookchin (Citation2006) was a complex, multifaceted character, who sought to overthrow mainstream capitalist society, and replace it with smaller scale, cooperative communities, that lived out the principles that he formulated over many years, defined under the rubric of ‘social ecology’. Bookchin (Citation2006) made a priority of translating ecological scientific principles derived as fact into real societal formations, and as such, looked to avoid the large scale, wasteful, inequitable and environmentally destructive effects of capitalism. Hence, his position on science, that is echoed in this paper, is to decouple science from capitalist exploitation and environmental harm. Bookchin’s (Citation2006) position of social ecology is crucial to this paper, in that society and ecology must be aligned and work co-dependently if the end of the world is to be avoided. André Gorz (Citation1979) was a Marxist critic of mainstream capitalism from the 1960s until his death in 2007 and sought to improve the lives of workers and their enslavement in unfair economic relations. As such, Gorz also wrote about ecology, but from a political and economic perspective, and in 1972, coined the phrase, ‘degrowth’, that has latterly come to prominence in terms of a rational and planned slowing of the economy to mitigate against negative environmental effects (Hickel, Citation2021). Degrowth is vital to the position of ecosophy outlined here, in that without attention to the economy, the self-same processes of world destruction that are endemic to capitalism will be repeated. Hence, in this article, the four positions of Guattari, Naess, Bookchin and Gorz are combined into the concept of ecosophy, not to diminish the differences in their positions, but to provide a clear and powerful means to examine the contemporary context through pedagogy, and to contribute purposefully to the philosophy of education. In sum, the position of this paper in terms of the analysis of the end of the world through cinema and the ten films that have been chosen for discussion below (), can be understood as ecosophical with a lateral movement between social ecology, ecosophy, degrowth and deep ecology (). It is essential that these four positions be included to strengthen the depth and longevity of the thinking on offer here, which needs to traverse societal formation, economics, and nature in addressing the end of the world scenarios captured by the ten films (). This action is in order to provide a heightened and subversive analysis of cinema that does not remain only on the level of cultural criticism but instantiates a new philosophy of education capable of contributing to climate change education (Reid, Citation2019).

The four positions of this article in are distinct, but laterally connected in a mode of fluidity and vitality (Kowalsky, Citation2014). This lateral movement is conceptually significant in that they support one another and open up analysis of the ten films () to the benefit of climate change education as new mappings of cinema, time, and the unconscious. Furthermore, even though the conceptual array for analysis used in this article comes from the historical period of the 1960 and 1970s, and gains cogency and impetus from the questioning of mainstream western mores during that time, their alignment also owes much to previous critical analysis of, for example, the Frankfurt School (Nelson & Grossberg, Citation1988). The members of the Frankfurt School witnessed the horrors and destruction of the Second World War, and critically analysed its aftermath that has been defined as the ‘Great Acceleration’ (McNeill, Citation2016), wherein global capitalism led by the U.S., competed with communism mostly in the form of the U.S.S.R. on the world stage for direction and control. The post-War, Great Acceleration has seen the direct and enormous spike in emissions and other human-produced pollutants, including carbon dioxide, which is directly linked with global warming, and the destabilisation of the Holocene living conditions that has resulted in the shift to the Anthropocene (Crutzen, Citation2002). Hence, even though the Frankfurt School did not specifically critically analyse global warming through their social theory, they may be seen as precursors and an underpinning movement behind what emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, and that is being put forward here in terms of ‘ecosophy’.

The ecosophy of this article does not take a backward step and relinquish the advances in critical and social thought put forward on by the Frankfurt School. Rather, the often-negative work of Walter Benjamin (Citation2008), Theodore Adorno (Citation2003), and Herbert Marcuse (Citation1955), is here reversed and made positive through its application in climate change education. Of course, each of these thinkers, though associated with the School, has made his own unique contributions to the field, yet in this essay, their combined thought works at the level of a grand refusal (Berman, Citation1989). This grand refusal functions as a mode of social and cultural thought that the Frankfurt School criticised; i.e., the mediocre, clichéd, meaningless, robotic, repetitive productions of capitalism, that are principally meant to sell products, and, as marketing spin, are patently hollow and banal. In contrast, the Frankfurt School brought forward critical thinking about consumer society and its products such as cinema, literature, music, and, indeed, the power of life and control, as Adorno (Citation1972) stated, ‘The culture industry is not the art of the consumer but rather the projection of the will of those in control onto their victims. The automatic self-reproduction of the status quo in its established forms is itself an expression of domination’, (p. 185). Thus, the ecosophy of this article and the cinema analysis below rests on this critical platform as sketched out by theorists such as Adorno (Citation2003, Citation1972), who took an uncompromising view on the mechanisation and technological assimilation of cultural production via capital. In general, the Frankfurt School presented a largely negative view of cultural production and human progress, and hence emphasized the destructive and world–annihilating potential of human action, for example, in the evolution of technology (Honneth, Citation1995). In contrast, this article, via deploying a laterally connected ecosophy as described above, tries to reverse this tendency, and put forward the combination of ecosophy, social ecology, degrowth and deep ecology (without its misanthropic tendency), with the intent of analysing end of the world scenarios in cinema, wherein images = matter (Cole & Bradley, Citation2016). The ecosophy of this article acts as a critical approach to the progress of human civilization, as described by Marcuse (Citation1955), yet simultaneously enables lateral and affective thinking about the subject, in a combinatory fashion. This argument depends not on a turn to mysticism or a new materialist metaphysics/theology about and as part of the physics of human action on nature as disembodied, but in genuinely synthesising human action in terms of the social, ecological and economic forces involved, and how these forces concurrently work as nature (Cole, Citation2020; Oliver & Gershman, Citation1989). This article does not proceed from a new materialist position because human agency is not flattened or aligned with/as matter, but resolved through ecosophy, and the ecosophical thinking about cinema.

The point here is that the Frankfurt School, whether through Adorno (Citation2003, Citation1972) or Marcuse (Citation1955) who expressed the mode in which society unconsciously destroys nature, have diagnosed a tendency in western culture without suggesting solutions. This diagnostic approach, whilst fruitful in terms of uncovering negative traits of human behaviour, culture and thought, do not help in terms of moving us towards a positive climate change education, as is the objective of this article. Rather, the ecosophy of this article () looks to differentiate the cultural analysis of cinema in terms of time, the unconscious, image and behaviour, and as the application of social ecology, ecosophy, degrowth and deep ecology to the contemporary situation. In sum, the combinatory action of the thinking involved with ecosophy, whilst building on the critical work of the Frankfurt School, goes beyond superficial and token responses to environmental damage borne out of guilt, and as diagnosed, for example, by Slavoj Žižek (Citation2011):

[T]his readiness to assume the guilt for the threats to our environment is deceptively reassuring: We like to be guilty since, if we are guilty, it all depends on us. We pull the strings of the catastrophe, so we can also save ourselves simply by changing our lives. What is really hard for us (at least in the West) to accept is that we are reduced to the role of a passive observer who sits and watches what our fate will be. To avoid this impotence, we engage in frantic, obsessive activities. We recycle old paper, we buy organic food, we install long-lasting light bulbs—whatever—just so we can be sure that we are doing something. We make our individual contribution like the soccer fan who supports his team in front of a TV screen at home, shouting and jumping from his seat, in the belief that this will somehow influence the game’s outcome.

Žižek (Citation2011, p. 423)

Films to be analysed

The ten films chosen for analysis depict end of the world scenarios. Hence, they contain a thesis on time in terms of when the end of the world will take place and what the effects on human society will be, given this thesis on time. Even though the films are fictional, important climate change education may be extracted from the films in term of the cinema-thinking that they evoke, and the matter-images (Cole & Bradley, Citation2016) they present. Climate change education is here realigned in terms of the laterally connected ecosophy above () and the pedagogy of cinema, so instead of giving a guide to climate change and its effects, the philosophy of education that is derived from the films is about time and human society once the end of the world has been designated. Importantly, the real facts of climate change that are proven by science sit within the thesis on time and society provided by the ecosophical reading of the films in this paper. In this context, each film is its own semiotic marker (Dawkins, Citation2005) and universe of meaning, epistemology and ontology on time, society and the end of the world, and as such, helps us to think ecosophically. In other words, every film is being excavated for images of philosophical content against the backdrop of ecosophy:

This is not ‘the end of the world’

The ten films listed above () imagine the end of the world. In this ecosophical essay, this imagining is not a metaphor, but depicts actual modes in which the end of the world could happen. As such, the ten films present narratives, conceptual clusters, and divergent through-lines that converge in the inter-connected nexus of the end of the world (Žižek, Citation2011). This analysis does not try to force, embellish, or present one scenario of the end of the world over any other, make a hierarchy of the films, or present an evaluation of the scenarios, and how they play out. Rather, these films present images that are laden with semiotic markers and ‘thought-provocations’ about what the end of the world looks like, and how these constructions relate to and diverge with respect to the manners in which the Anthropocene and sixth great extinction event are unfolding today (Cole, Citation2017, Citation2021). In effect, the lateral ecosophical perspective of this article, merges and separates in relation to the analysis and synthesis of the films, not as static objects, but as images held in place by the framing of the end of world as a schema [time-human society] and against the scientific facts of climate change. This schema is the real/material constellation of ideas and thoughts that compose the philosophy of education that we ultimately want to take away from this analysis as pedagogy in and about climate change.

Human society and the end of the world

Clearly, the first and dominant effect on human society of the end of the world is panic, or as a flight response. The established norms of human society are quickly abandoned in favour of trying to survive at all costs, and in many cases, this means seeking safety and shelter, whether it be specifically constructed arks in the case of 2012, or in an underground bunker in Greenland, in the film of the same name. In post-apocalypse cinema, such as 12 Monkeys, The Road, or Mad Max, human society survives in a radically curtailed form, in these films as; herded together and caged underground, wandering the scorched earth in small groups trying to survive, living in isolated and lawless communities, and subject to extreme violence. In two of the films, The Day After Tomorrow and the Tomorrow War, the government is able to mount a coordinated and militaristic response to the threat of the end of the world, in the case of the Tomorrow War, by sending hastily recruited soldiers to the future to battle with alien predators, in The Day After Tomorrow, to evacuate south in the face of rapidly advancing climate change. Interestingly, these state-backed responses to the end of the world echo the ways in which governments are often responding to climate change through resource and capital-intensive solutions but neglect the ecosophical work being done here. Human society in Melancholia and Apocalypse Now responds through despair and madness, even though we are only given a glimpse of this destiny by following a tiny minority of characters. Lastly, the connection to human society between the catastrophic series of errors in Dr Strangelove, leads to the implementation of military protocols to ease the threat of the release of the Doomsday device, though these protocols turn out to be useless, when handed the precise set of circumstances that the film presents and ultimately parodies.

In the specific terms of the laterally connected ecosophy of this article, the different levels and modes of breakdown of human society signalled by the end of the world, present an inter-connected nexus between social ecology and deep ecology (Næss, Citation1990). In films that depict large-scale planetary destruction, the remnants of human society survive on already collected resources (i.e., 2012, 12 Monkeys, Greenland). Hence, the ecology of the Earth no longer provides sustenance for the human population, which must use previously harvested resources, or an artificially created means to live (Bookchin, Citation2006). Films that depict the imminent end of the world become embroiled in human psychology, and therefore any exterior ecology becomes internalised, as part of the interior thought processes, nightmares and imaginative recreation of the world as thinking, desire and desolation. Furthermore, as the realization that there is no future (or a radically change future) becomes apparent, the human mind struggles to adjust and starts to fracture (Melancholia, Dr Strangelove, and Apocalypse Now). In The Road, a planetary extinction event has decimated the Earth, and human existence concerns survival, with barely any ecology left besides burnt trees, a few scattered buildings and other people. This new ecology brings a constant battle to find food to survive and to not be killed by others. Such an ecological scenario is to extent repeated in Mad Max, though the ecological damage is not as extensive. In contrast, in The Day After Tomorrow, planetary ecological conditions for human flourishing still exist, but due to climate change, whole societies have to move, which would have enormous implications for the social ecology of the human populations, as they have to establish themselves in new locations. This model for social change closely fits with the scientific modelling of what will happen in the future according to climate change. In The Tomorrow War, humans are the target for alien predators, and as such, ecological considerations are abandoned in the face of the attempt to fight these aliens. In this narrative, all human ingenuity and established relationships with the world are diverted to exterminate the threat to human life (or be exterminated). All films correspond to a post-work model of human functioning with elements of degrowth (Hickel, Citation2021), wherein the present capitalist day is not depicted except for the time travel films that travel back to today (12 Moneys, The Tomorrow War). Lastly, Apocalypse Now presents a new ecological arrangement between human society and the ecology of the Earth that blends modern and ancient formations, to find a new harmony at the end of the world.

Time and the end of the world

The films depict the malleability of time, and that diverges from the conception of time as mechanical, linear and non-contingent (Cole, Citation2020, Citation2021). Such malleability of time is frequently parallel to scientific models of climate change, that include factors such as feedback, that are highly contextually variant and subject to oscillation, given hybrid anthropogenic and natural input processes (Bremer & Meisch, Citation2017). Many films include a certain date and time for the end of the world, that begins a countdown to that date and time, and, as such, the intervening time becomes a focus for getting things done in terms of preparation for the apocalypse, e.g., seeking shelter (2012, Greenland). Films in which the end of the world has already happened (12 Monkeys, The Road, Mad Max) demonstrate a time of stagnation, repetition and life as devoid of the measurement and segmentation of/in time. Several of the films include the possibility of time travel (12 Monkeys, The Tomorrow War), wherein characters can travel back and forth between ‘pre’ and ‘post’ apocalypse worlds. Consequently, the contemporary time of capitalism, work and life, is figured as an anchor for the changes in time post the end of the world event; in 12 Monkeys, time is compromised by humans being herded together underground in cages, in The Tomorrow War, future time is refigured in terms of exterminating predatory aliens before they wipe out the entire human species. In Melancholia, time is bent and twisted by the approach of the planet that will collide with the Earth, causing a mass extinction event. In this context, time is structured and restructured along the lines of hopelessness, disbelief, suicide and the impotency to act. In The Day After Tomorrow, time is realigned according to positive climate feedback loops, and the shifting development of extreme weather patterns, hostile to the survival of human life, again following current scientific modelling of climate change. In Dr Strangelove, time is remade as contingency and error, as the film flips between a doomed bomber crew and the efforts of the control centre to turn back the crew from carrying out its mission. In this context, time is reformed as a series of interconnected contingencies that show what could happen in a worse case, end of the world, scenario (Žižek, Citation2011). In Apocalypse Now, time is reformulated as following the snaking river upstream, and through a final meeting with Kurtz, madness, and the end of western civilization (and the potential birth of a new one). In all films that do not include time travel to the present day, time is altered, and the everyday, measured and monitored, work/time/capital/debt = labour equations are abolished. However, this abolishing does not mean freedom, but inculcates other systems and necessities, such as finding shelter and enough food to stay alive.

With respect to ecosophy, the variations in the time dimension demonstrated by the ten films, shows how the manipulation of the end of the world in cinema causes perturbation and fractures in ecological relations (Guattari, Citation2000). The time of human societal relations that has been built, taken apart and reassembled through history, as civilizations have grown and fallen; is completely reorganized, as the end of the world funnels these systems along divergent lines (except for the films with time travel to the present day). In the films that include a countdown to the end of the world (2012, Greenland), the ecosophy of time is reorganized in terms of doing everything necessary before the countdown expires, like the designated time until a bomb detonates. Films that include post-apocalypse scenarios (The Road, Mad Max), have an ecosophical time that is pre-modern, continuous, and that rests along the lines of pre-civilization, even though both films include the metaphor of the road as the remnant of human ecological organization. The ecosophy of time of Melancholia is a strange trip inside the minds of a small number of characters that progressively become aware of their certain deaths. Similarly, the ecosophy of Apocalypse Now depicts new and weird landscapes of time and hallucination that become apparent as the assumptions in western civilization are questioned, and the characters venture further into unknown territory. The ecosophy of time in 12 Monkeys and Dr Strangelove is frantic and absurd, as time is fractured by coincidences, accidents, and circumstances that are unforeseen and misunderstood. In the Day After Tomorrow, it might be tempting to reassert the dualism between human and natural time, as catastrophic and abrupt climate change (nature) threatens to decimate human society, but here this dualism is reassessed according to the laterally connected ecosophy above (). Hence, it is not a matter of dividing climate change and human action in time, but of perceiving them as wholly related. Hence, the ecosophy of this paper bridges the gaps between the time of the end of the world according to the science of climate change, and the times of human experience, society and natural processes. Lastly, the film Tomorrow War introduces an alien ecosophy, in that human society is reorganized in the future according to the characteristics and potential of the alien attackers, which determines a new time of escaping and destroying these aliens. Lastly, all films except parts of the two time travel narratives (12 Monkeys, Tomorrow War) present us with variations on the themes of degrowth time, in that the creation of surplus value of capitalist accumulation (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1984) has been abandoned.

Conclusion(s)

This essay deliberately takes a retrospective look at the counter-culture concept of ecosophy and attempts to revive it for a contemporary audience. In contrast to new materialist and posthuman approaches to the philosophy of education (Bardin, Citation2021; Mazzei & Jackson, Citation2017; Petersen, 2018), this essay does not seek to erase the human in contemporary education, nor build a metaphysics from matter with humans only participating marginally (cf., Wakefield et al., Citation2021). Rather, this essay conjoins ecosophy with social ecology, degrowth and deep ecology to deliberately forge a position wherein new thought about the philosophy of education can happen through the analysis of cinema (even though this new thought has a retrospective element). More specifically, this essay works on providing an emergent perspective on the end of the world from images taken from ten films, wherein the images are augmented and focused through the application of ecosophy, as a positive means to analyse film. In sum, this study found that:

The dimension of time is malleable, and has many layers and directions given the complexity of the end of the world scenarios that we find ourselves embedded within and as represented by cinema narratives. The ecosophy of this article takes the malleability and inter-dimensional perspective on time as a positive attribute for encouraging action on climate change through education (Alhadeff-Jones, Citation2017). As such, the ecosophy of this article works to connect the facts of climate change proven by science with a positive scheme of action. It is hypothesized that the new insights into time that such exploration can produce, will lead to learning further about the different layers and qualities on time that collective action to make a different future encourages (e.g., working together to remedy climate change).

Human society must change to stave off the end of the world. Of course, there have been many variant propositions, theories and manuals to transform human society. This article takes ecosophy as a means to change society according to the proven facts of scientific climate change, beyond capitalist interference, and through cinematic analysis. The ecosophical analysis of cinema congeals in a philosophy of education that challenges reactionary, panic-stricken approaches to the escalating catastrophes that will accumulate as climate change accelerates (Ojala et al., Citation2021). Rather, this article suggests that the forward planning and organization of ecosophy is at one with the key occurrences that will embody climate change education, as under its rubric, human nature is entirely connected to society, the economy and nature (Tynan, Citation2021). In this sense, ecosophy acts as a factor of augmentation and platform for dealing with the future of climate change, and not allowing it to overwhelm us. From this perspective, the practice of ecosophy lies at the heart of future climate change education and its philosophy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David R. Cole

David R. Cole has been working in the field of ‘Deleuze and Education’ since the 1990s, where he studied Continental philosophy at the University of Warwick. He has contributed more than 100+ significant publications and 15 books in this area. Recently, he has been researching on climate change through the concept of the Anthropocene, and has started an online research institute to further this aim: https://iiraorg.com/. He is also an Associate Professor at Western Sydney in teacher education and cultural analysis.

References

- Adorno, T. W. (1972). The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture (J. M. Bernstein, Ed., 1st ed.). Routledge.

- Adorno, T. W. (2003). Negative dialectics (E.B. Ashton, Trans.). Routledge.

- Alhadeff-Jones, M. (2017). Time and the rhythms of emancipatory education: Rethinking the temporal complexity of self and society. Routledge.

- Bardin, A. (2021). Simondon contra new materialism: Political anthropology reloaded. Theory, Culture & Society, 38(5), 25–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211012047

- Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago Press.

- Benjamin, W. (2008). The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility, and other writings on media (M. W. Jennings, B. Doherty, & T. Y. Levin, Eds.). Belknap Press.

- Berman, R. A. (1989). Modern culture and critical theory: Art, politics, and the legacy of the Frankfurt School. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso Books.

- Bonefeld, W., & Tischler, S. (2002). What is to be done? Leninism, anti-Leninist Marxism and the Question of Revolution today. Capital & Class, 83, 196.

- Bookchin, M. (2006). Social ecology and communalism. AK Press.

- Bowie, M. (1993). Lacan. Harvard University Press.

- Bremer, S., & Meisch, S. (2017). Co‐production in climate change research: Reviewing different perspectives. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 8(6), e482.

- Chaplin, T., & Mooney, J. E. P. (2017). The global 1960s: Convention, contest and counterculture. Routledge.

- Cole, D. R. (2017). Black Sun: The singularity at the heart of the Anthropocene. https://iiraorg.com/2017/07/31/first-blog-post

- Cole, D. R. (2020). Learning to think in the anthropocene: What can Deleuze-Guattari teach us? In K. Maiti & S. Chakraborty (Eds.), Global perspectives on eco-aesthetics and eco-ethics: A green critique (pp. 31–47). Lexington Press.

- Cole, D. R. (2021). Education, the anthropocene, and Deleuze/Guattari. Brill.

- Cole, D. R., & Bradley, J. P. (2016). A pedagogy of cinema. Sense Publishers.

- Cole, D. R., & Mirzaei Rafe, M. (2017). Conceptual ecologies for educational research through Deleuze, Guattari and Whitehead. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(9), 849–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1336805

- Crutzen, P. J. (2002). Geology of mankind. Nature, 415(6867), 23. https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a

- Dawkins, R. (2005). Deleuze, Peirce, and the cinematic sign. Semiotic Review of Books, 15(2), 8–12.

- Deleuze, G. (1989). Cinema 2: The time-image (H. Tomlinson & R. Galeta, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1992). Cinema 1: The movement-image (H. Tomlinson & B. Habberjam, Trans.). The Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1984). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism & schizophrenia (R. Hurley, M. Steen, & H. R. Lane, Trans.). The Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia II (B. Massumi, Trans.). The Athlone Press.

- Dryzek, J. S., & Pickering, J. (2018). The politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford University Press.

- Gorz, A. (1979). Ecology as politics (P. Vigderman & J. Cloud, Trans.). South End Press.

- Guattari, F. (2000). The three ecologies (I. Pindar & P. Sutton, Trans.) Athlone Press.

- Hickel, J. (2021). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations, 18(7), 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1812222

- Honneth, A. (1995). The fragmented world of the social: Essays in social and political philosophy. Suny Press.

- Kallis, G., Demaria, F., & D’Alisa, G. (2014). Introduction: Degrowth. In G. D’Alisa, F. Demaria, & G. Kallis (Eds.), Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era (pp. 29–46). Routledge.

- Kowalsky, N. (2014). Whatever happened to deep ecology? The Trumpeter, 30(2), 95–100.

- Marcuse, H. (1955). Eros and civilization. Beacon.

- Mazzei, L. A., & Jackson, A. Y. (2017). Voice in the agentic assemblage. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(11), 1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1159176

- McNeill, J. R. (2016). The great acceleration. Harvard University Press.

- Mickey, S. (2014). On the verge of a planetary civilization: A philosophy of integral ecology. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Naess, A. (1990). Ecology, community and lifestyle: Outline of an ecosophy. Cambridge university press.

- Nelson, C., & Grossberg, L. (Eds.). (1988). Marxism and the interpretation of culture. University of Illinois Press.

- Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C. A., & Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, worry and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

- Oliver, D. W., & Gershman, K. W. (1989). Education, modernity, and fractured meaning: Toward a process theory of teaching and learning. SUNY Press.

- Petersen, E. B. (2018). ‘Data found us’: A critique of some new materialist tropes in educational research. Research in Education, 101(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523718792161

- Reid, A. (2019). Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1664075

- Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P., & McNeill, J. (2011). The Anthropocene: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences, 369(1938), 842–867. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0327

- Tynan, A. (2021). Aporias of ecological thought. Theory, Culture & Society, 0(0), 026327642110392–026327642110319. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632764211039280

- Vanderheiden, S. (2005). Eco-terrorism or justified resistance? Radical environmentalism and the “war on terror”. Politics & Society, 33(3), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329205278462

- Wakefield, S., Chandler, D., & Grove, K. (2021). The asymmetrical anthropocene: Resilience and the limits of posthumanism. Cultural Geographies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/14744740211029278

- Weintrobe, S. (Ed.). (2013). Engaging with climate change: Psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspectives. Routledge.

- Žižek, S. (2011). Living in the end times. Verso.