Abstract

This conceptual paper argues for the reconfiguring of Intercultural Communication Education (ICE) through a dialogical engagement with Istina (Truth) and Pravda (Truth in Justice). The paper argues that the field of ICE is predominantly characterised by normative conceptualisations of truth (e.g., characterised by fixed or ‘objective’ interpretations of language and culture) or hyper-relativist post-truth conceptualisations (e.g., non-essentialist approaches to ICE). This conceptual paper, therefore, addresses the following research question: To what extent can a dialogical approach to truth address and redress epistemic power imbalances in ICE? Through engaging with Russian language and the dialogical approach of Mikhail Bakhtin a non-normative approach for ICE is proposed. The paper conceptually argues in moving beyond the binary of normative and post-truth interpretations in ICE through dialogism. The paper serves at an important juncture amidst calls that the field of ICE is characterised by epistemic violence and epistemic power imbalances. The proposed dialogical approach to truth in ICE aims to redress epistemic imbalances in arguing for a form of non-normative dialogical ethics.

Introduction: Intercultural Communication Education and the problem of truth

In this conceptual paper I argue for reconfiguring ICE through a dialogical engagement with the Russian language. In engaging with the work of Mikhail Bakhtin I argue that problematising the site between Istina (Truth) and Pravda (Truth in Justice) can serve to address and redress the problem of truth in ICE. To put it simply, this conceptual paper addresses the following research question: To what extent can a dialogical approach to truth address and redress epistemic power imbalances in Intercultural Communication Education (ICE)?

The Bakhtin being subjected to critical evaluation in this conceptual paper is in recognition of Bakhtin’s early phenomenological works on ‘Art and Responsibility’ and ‘Towards a Philosophy of the Act’ (Hirschkop, Citation2021). As Tihanov (Citation2021) notes though, Bakhtin himself in his later works was to move beyond (and perhaps reject) these phenomenological perspectives in favour of dialogism. It is important to note that the conceptual application and coherence of Bakhtin’s works render some notions ‘untranslatable’ (Tihanov, Citation2021, p. 667). Therefore, the position I adopt in this conceptual paper is in recognition of the varying philosophical shifts and influences found in Bakhtin’s work and which has been said to result in the construction of many Bakhtin’s found within Bakhtin’s work (Brandist, Citation2002). A thorough mapping of Bakhtinian concepts can be found in later sections of this paper where I demonstrate the conceptual positioning of my translations.

The polysemy of Bakhtinian concepts and of the ways in which ICE can be conceptually positioned seemingly goes hand in hand. The various guises of interculturality, either defined or conceptualised, as Intercultural Education, Intercultural Communication, or Intercultural Communication Education (ICE) are not new, and the history contained within the conceptual frameworks can be described as turbulent (at best!) (Dervin & Tournebise, Citation2013; Simpson & Dervin, Citation2020). This conceptual paper uses Intercultural Communication Education (ICE) as communication and education cannot be separated – instead, the relationship between communication and education (and vice versa) should be understood through a dialogical symbiosis whereby communication and education function through constantly (re)defining, (re)constituting and (re)working one another (Simpson, Citation2020). There has been a long-held assumption in intercultural education and in intercultural communication that forms of ICE should function as a precursor to successful intercultural communication (R’boul, Citation2021). The notion of successful intercultural communication which is biased (Holliday, Citation2011), firstly, assumes that in binary opposition intercultural communication events/situations/encounters are often characterised, or will be characterised, through miscommunications. Secondly, contained within this assumption is that often static forms of ‘culture’ or content which can be described as ‘cultural’ can be attributed to particular individuals and/or groups in making them ‘different’.

As previous critical intercultural communication (e.g., Ferri, Citation2020) and critical intercultural education studies (e.g., Dasli, Citation2019) have shown the discourses contained within this conceptualisation of culture (which often is presented as ‘knowledge’) essentialises individuals and/or groups through stereotypical labels. Thirdly, the categorisation and ‘boxing-in’ of the subject in Intercultural events/situations/encounters often leads to the reproduction of essentialist discourses and representations which exacerbates ‘the problem’ of cultural differences in intercultural encounters (Dervin, Citation2016). This discussion is succinctly put by Ferri (Citation2018) who argues that binary logics and practices in intercultural communication create a ‘uniform system of truth ordered according to a series of oppositions, which marginalise the particularity of the concrete and singular aspects of individuals and of existence in general’ (Ferri, Citation2018, p. 5). In this sense, truth and knowledge about self and the other are conceptualised from the modernist position of the ‘knowing subject’ who is the rationalist bearer and interpreter of all given knowledge and truth (Esposito, Citation2012). But how did the field of ICE get to this point? And perhaps more importantly, how can the field of ICE move beyond the conceptual impasse surrounding truth?

Truth and post-truth in Intercultural Communication Education: A detour through language and philosophy

The field of ICE can arguably be dated by to the 1950s and Edward T. Hall’s (Citation1959) publication The Silent Language. Edward T. Hall, an anthropologist who worked for the US State Department was influential in developing a generalisable matrix to analyse what Hall called different ‘cultures’, but were in fact, countries. Such studies engendered logics and practices that the other can be observed (i.e., in ‘their context’, ‘in their country, ‘in their language’) or that there was some observable other world which needed to be described (Ferri, Citation2018). In this sense, the subject in ICE has been, and continues to be, posited as an ‘all knowing’ subject which on the one hand can be observable (in a tangible sense) and on the other is normatively rationalised thorough the gaze of the observer (Ferri, Citation2020).

The knowing subject in ICE, has arguably since Michael Byram’s (Citation1997) Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) model, been positioned as the centrepiece through which successful intercultural communication should be facilitated through. The problems associated with the primacy and exclusivity of the formula, self = knowing subject, in Byram’s (Citation1997) ICC model has been criticised by critical intercultural communication education scholars. Hoff (Citation2014) argues that Byram’s ICC model primarily focuses on how the self understands and obtains intercultural communicative competencies through encounters with the other from the basis of self, rather, than self-other which means that the self-other relationship is intrinsically suspectable to power imbalances. For Simpson and Dervin (Citation2020), the subject’s self-centric conceptualisation in Byram’s ICC model is flawed as it does not take into consideration the instability and fluidity which often characterises self-other dynamics (e.g., the construction and negotiation of identities, values and beliefs). The danger here is that this rationalist approach to ICE translates the self as a complete, unified and singular subject who is all knowledgeable. Truth, in Byram’s ICC model, is conceptualised normatively and singularly from the position of self which is always in binary opposition to the other (Dasli, Citation2019). Moreover, there is no way of knowing whether intercultural competencies (e.g., the values, principles and skills) can be actually obtained/understood or not despite attempts in the field to develop intercultural competence assessments as indicators or metrics of truth (see Deardorff, Citation2009, Citation2019).

In more recent years, through postmodernist and poststructuralist influences on the social sciences, ICE has become influenced by the relationship between knowledge and power (Ferri, Citation2018). Ferri (Citation2018) in citing Foucault (Citation2010) shows that, ‘power is embodied in social practices and in discourses that create regimes of truth, which structure accepted forms of knowledge and divisions between what is true and false’ (Ferri, Citation2018, p. 9). Despite the popularity of poststructuralist approaches in ICE, the conceptual inertia and limitations of some poststructuralist approaches in ICE have been documented (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). One example can be found in the ways in which regimes of truth in ICE function as regimes of legitimisation in terms of what knowledge is considered to be legitimate, what is marginal and what is considered illegitimate, especially when researchers claim to be giving voice to the other and/or the field (R’boul, Citation2022). These questions have failed to be adequately conceptualised in terms of addressing decolonialisation in ICE (Aman, Citation2017). As a result, inherent ‘Western-centric’ and ‘Anglo-centric’ logics and practices found in ICE mean that epistemic violence is reproduced time and time again (Ferri, Citation2022).

In citing Jean-Francois Lyotard (Citation1984) MacDonald & O’Regan (Citation2013) argue that the poststructuralist turn in the field of intercultural communication has engendered certain risks that critical-transformational truths simply become elements of a wider intercultural ‘meta-narrative’ – these risks that the authors are eluding here relate to how certain truths can be manipulated for certain social and/or political means. In their article MacDonald and O’Regan (Citation2013) give the example of how critical-transformational discourses are seen to be ‘truer’ than e.g., some religious beliefs or values, yet essentialist and/or racist discourses may be contained within critical-transformational discourses which could mean the critical-transformational discourses would, in this sense, be contradicting their own critical spirit. Perhaps this is an indication that the critical and discursive turn in ICE (Dasli and Diaz, Citation2017) has resulted in a hyper-relative construction of knowledge whereby ‘everything goes’ (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). Seemingly in response to this epistemological crisis, Zembylas (Citation2022) argues for affirmative critique, instead of negative critique, in dealing with the conceptual impasse of post-truth discourses and power relations which perpetuate and continually engender the binary dichotomies of us versus them.

Arguably, education and all socio-political apparatuses throughout society are functioning in times of post-truth (Nally, Citation2021; Peters, Citation2017; Peters et al., Citation2022). Post-truth can mean different things to different actors depending on the theoretical and epistemological position adopted (Nally, Citation2021). In drawing on Hann (Citation2016), I focus on the social lives of concepts in order to problematise the etymological foundation of the meanings found within the concepts. In using the online etymology dictionary if one traces back the word truth, the noun truth derives from Old English triewð (West Saxon), treowð (Mercian) meaning ‘faith, faithfulness, fidelity, loyalty; veracity, quality of being true; pledge, covenant’ (Etymonline, Citation2022). In this sense, etymologically ‘truth’ carries the connotations of faithfulness and loyalty, aspects which are not necessarily ‘objective’, if anything they are inherently subjective. According to Chandler & Munday’s (Citation2020) Dictionary of Media and Communication post-truth can be defined as ‘an anti-intellectual cultural and political climate in which facts and rationality are subordinated to familiar narratives that have popular resonance, substantiated only by anecdotal evidence’ (Chandler & Munday, Citation2020). In their definition the authors go on to add ‘This [post-truth] is a form of radical relativism indifferent to any distinction between fact and fiction—a stance ironically reminiscent of the intellectual excesses of postmodernism’ (ibid). For Schindler (Citation2020) the distinctions between truth and post-truth have failed to acknowledge ‘that the relativisation of facts is equally a feature of ideological thinking (Schindler, Citation2020, p. 376) insofar that researchers have constructed binary distinctions between ‘ideology-as-naturalisation and theory-as-relativisation’ (Schindler, Citation2020, p. 377). This distinction often produces a discursive and epistemological vacuum that one should be, and must be, on one side of a given argument which often reproduces binary logics and practices in the construction of knowledge contained in ICE (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021).

In continuing the problematision of the social lives of concepts I argue for an engagement with Russian language and philosophy to rethink truth and post-truth in ICE. The Russian word istina [истина] has a dual function which makes the word both ontological and epistemological, ontological istina means: ‘what is, what truly exists’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014c, p. 513). The epistemological function of istina refers to statements which confirm reality (i.e., knowledge) ‘this role is secondary and always in relation to the ontological function of istina (Vasylchenko, Citation2014c, p. 513). Here, ‘‘the logical sense of “veracity” is, moreover, translated by a different Russian noun, istinnost’ [истинность], so that istina and istinnost’ are translated into English using the same word, “truth”’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014c, p. 513)’. Florensky (Citation2018, p. 14) shows that the ‘Russian word for “truth,” istina, is linguistically close to the verb “to be”: istina—estina’. For Florensky, istina, therefore, ‘signifies absolute self-identity and hence, self-equality’ (Florensky, Citation2018, p. 14).

Another way of conceptualising istina is through the thought of the Russian rationalist Philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, who argues ‘what truth (istina) is, one must at least say what it is not. It is not in the realm of the separate and isolated self’ (Solovyov, Citation1965, p. 213). In this sense, istina is rationalised in the mind of the subject and what the subject identifies as can be understood through the formular: self = self-identity. Rationalist notions of istina through the ways in which normative conceptualisations of truth are engendered can also relate to how versions of ‘truth’ are constituted in ICE in the sense that if a speaker says that x is ‘their culture’ or that they speak y as a language the knowledge about the notions is often ‘taken as a given’, with scant criticality nor contestation (Holliday & MacDonald, Citation2020). It is almost as if whatever a speaker says will be conceptualised as a rational piece of unquestionable ‘objective’ information, i.e., truth (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). For example, Rendall (Citation2014) argues, ‘the French word culture, like its analogues in various European languages, ‘comes from the Latin cultura, which designates agriculture and the transformation of nature, implying a relationship to places and to gods (colere, the verb from which it derives, also means “inhabit” and “worship”)’ (Rendall, Citation2014, p. 191). It seems that the way the word culture is often used in ICE often reproduces the religiosity of gods, as the notion been turned into an artifact of worship insofar that it functions as a form of dogma which cannot be questioned (Simpson, Citation2020). In this sense culture, negates notions of identity and diversity, in the sense of pluralist conceptualisations, as it encloses the intersubjectivities of the subject – the subject simply cannot escape the emasculation of culture, culture acts as a fixed binding point to which the subject cannot escape (Phillips, Citation2009).

Alternatively, Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev views istina (truth) from an ontologically dynamic and anti-rationalist perspective:

‘Rationalism is something different from the abstraction of reason from the whole [sic] Man, from humanity, and therefore it is anti-human even if at times it seeks to enter the lists on behalf of the liberation of [sic] Man’ (Berdyaev, Citation1962, p. 22).

Truth as an epistemological act: From the knowing subject to the acting subject

Mikhail Bakhtin’s (Citation2012) collection of essays (2012) have had wide impact and are used throughout the humanities and social sciences due to the (Citation1981) translation of Bakhtin’s work into English The Dialogic Imagination. Other publications such as Toward a Philosophy of the Act (1993) are equally as well cited. As I (Simpson & Dervin, Citation2017) and others have shown (Brandist, Citation2002, Citation2015) on Bakhtin’s publications that there are many translation inaccuracies and conceptual misunderstandings, from Russian to English, associated with the translations of Bakhtin’s works. Despite this though, Bakhtin is still widely popular.

Before discussing Bakhtin’s work it is important to conceptualise the relationship between act and truth in Russian. The Russian word postupok [пοступοк] does not have a translation equivalence in English but perhaps the word closest is ‘act’. Postupok [пοступοк] ‘comes from the Old Russian noun postup [пοступ], “movement, action, act” and, finally, the verb stupat [ступать], “to walk, pace”’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 811). Etymologically, postupok thus means ‘“the step one has taken”’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 811). Postupok, meaning in the steps one has taken, should be understood as a reflexive process of constant critique and (re)evaluation. This critique and (re)evaluation is determined by the ethical praxis of the self-other relationship. The ethical landscape across which the act (postupok) functions can be understood though the notion svoboda (freedom). The Russian term ‘svoboda [свобода] (meaning freedom) comes from the Slavic possessive pronoun svoj [свой], which means belonging to the person and is rendered, depending on the context by “(my, your, his, our, your, their) own” (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 1105).

Vasylchenko (Citation2014b), argues,

“Svoboda reveals its structure in the novels of Dostoyevsky, whose characters are perpetually in intimate confrontations with Others (drugoj [другой], derived from drug [друг], “friend”), representing the entirety of the universe. The character must choose between the caritas of total responsibility for oneself and the universe, on the one hand, and the total diabolical destruction of “everything is permitted” (vsedozvolennost’ [вседозволенность], derived from volja), on the other” (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 1106).

The plain across which Svoboda (freedom) functions is through the perpetual relationality of the self-other relationship, enacted through, co-being and co-existence. A metaphor for the ‘act[ion]’ in ICE is the “non-alibi in being” (ne-alibi v bytii [не-алиби в бьɪтии]) (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). One has no moral alibi: one cannot escape neither one’s own singularity (i.e., one cannot transcend into something other) nor lose one’s own positionality . For Bakhtin (Citation1993), “non-alibi in being” [не-алиби в бьɪтии] is ‘essential for individual responsibility: to give this position up is also to lose one own’s position as an ethical being’ (Brandist, Citation2002, p. 39).

In contrast to Berdyaev’s conceptualisation of truth through istina, Bakhtin instead, explores the dialogical relationship between istina (truth) and pravda (truth in justice). For Bakhtin, the subject ‘is no longer the knowing subject but the acting subject’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 515). The epistemological function of istina remains but the ontological function does not: for Bakhtin, Being is Being (Bakhtin, Citation1993), which means it is no longer an ontological question of whether being exists because both the self and the other is present. In this sense, ‘“What truly exists” is not istina (truth), but postupok (act), an act invested with Pravda (truth in justice) (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 515)’. Bakhtin argues that istina as truth cannot be the basis for ethical praxis as normative truths and knowledge totalise the subject (Hirschkop, Citation1998). For Bakhtin, therefore, ‘the world of “what is,” within which postupok (act) takes place, is turned into what Bakhtin (Citation1993) calls a being-event (bytie-sobytie). With this term Bakhtin introduces an etymological metaphor: sobytie means “event,” but literally so-bytie signifies “co-being” [and] “co-existence”’(Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 515).

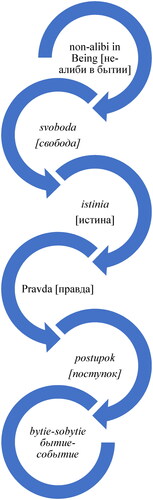

A summary of the key terms and their translation based on a Bakhtinian interpretation can be found in below:

For Bakhtin, ‘the theoretical world with its “abstract truth (otvlečënnaja istina [отвлечённая истина]),” is incapable of containing postupok [поступок] (an ethical act). Contrasting “theoretical abstraction” to what Bakhtin terms “participating thought,” one that considers the being “inside the act (postupok),”’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 515) in which Bakhtin proposes to move beyond rationalism (Bakhtin, Citation1993). In this sense, ‘inside the act’ means that truth is an intersubjective movement co-experienced by the self and other simultaneously, for Bakhtin, truth is not an external abstraction or an act that the self does singularly. Bakhtin argues that ‘Pravda does not exclude theoretical istina. On the contrary, it assumes and completes it’ (Vasylchenko, Citation2014b, 515) through co-being and the (ethical) responsibilities of the act (Bakhtin, Citation1993).

Bakhtin articulates,

‘The entire infinite context of possible human theoretical knowledge-science-

must become something answerably known for myself as a unique participant, and this does not in the least diminish and distort the autonomous truth [istina] of theoretical knowledge, but, on the contrary, complements it to the point where it becomes compellently valid truth-justice [pravda]’ (Bakhtin, Citation1993, p. 49).

At this juncture, it is important to note that the Russian to English translations, as is commonplace when translating from any language, often means the meanings and philosophies contained within the words are untranslatable (hence why I have stressed the use of the original Russian words) (Cassin et al., Citation2014). Therefore, should be used as a guide for dialogue and critical exploration (in true Bakhtinian spirit) rather than a doxa to follow.

Table 1. Translations of key concepts (my translation).

A dialogical non-normative approach for Intercultural Communication Education

Mikhail Bakhtin’s scholarship has been influential in ICE for decades (see Meeuwis, Citation1994; Min, Citation2001; Xu, Citation2013). In recent times, there has been scholarly interest in engaging with Bakhtin’s work as an alternative site to rework the theoretical conceptualisations of ICE from normative perspectives (e.g., Byram, Citation1997) to non-normative perspectives (Simpson & Dervin, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020; Simpson, Citation2020). This engagement has focused on moving away from understanding the subject through the formular A = A, in the sense, that the self does not correspond to itself, a dialogic interpretation of the self is that the self is influenced and shaped by interactions with others (Bakhtin, Citation2012). For Bakhtin, the subject is constructed by the self-other relationship insofar that identity does not mean self-identity (e.g., I was born in the UK therefore I am British), instead, identity corresponds to the simultaneous interanimation of multiple voices (Bakhtin, Citation2012). For Bakhtin multiple voices are important as they highlight that language, identities, and being, are always co-constructed, negotiated and performed with others. The self does not function in a vacuum. In this sense, the self, and one’s social realities, are constructed thorough dialogical relations.

To reconfigure ICE my argument is that the dialogical relationship between istina and pravda must be included at the heart of rethinking ICE. In this approach the epistemological function of istina is to challenge normative assumptions about truth and knowledge. Istina (truth) is constantly accentuated and reaccentuated through the dialogical relationality of the self and the other which constitutes postupok (the ethical act) (Vasylchenko, Citation2014a). The Bakhtinian notion of crisis of outsideness means that the ethical praxis and relationship between self and other can never be maintained (Bakhtin, Citation2012). To put it simply one can never know what the other demands from us, what they are thinking, what they are feeling and so forth. The crisis of outsideness does not presuppose that the self and other have to reach a mutual agreement, nor does it presuppose that the self and other can ever understand one another nor does it presuppose that the self and other can ever be reconciled to one another. On the contrary, the crises of outsideness recognises that self and other may never be able to speak a conceptual language to one another (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). The relationship between pravda and postupok can be problematised as a space to critique perceived ‘truths’ and perceived forms of knowledge (i.e., normative concepts, values and beliefs) insofar that istina and pravda should be conceptualised non-normatively to question epistemological knowledge istina in ICE and the non-normative ethics of the (Intercultural) act postupok.

In the figure below. Based on the Bakhtinian concepts discussed I offer a model to reconfigure ICE ().

Figure 1. Revised figure from (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021, p. 103). ICE reconfigured.

In this sense, truth is revealed in co-acts of co-being. In ICE this means going beyond the dogma that ‘truth’ is wholly actualised through the complete rational self – instead, truth is the participatory interanimation of the self and other co-constructing and negotiating knowledge together. Truth is not an external abstraction nor is it fixed nor singular, instead, the act postupok demands that there are ethical responsibilities for both the self and other meaning, knowledge and the relationships constructed through knowledge, need to be constantly revised and questioned (Bakhtin, Citation1993).

For example, epistemological truth Istina can be used to critique essentialist knowledge and ‘truths’ (e.g., stereotypes about language and ‘culture’ (Matusov & Marjanovic-Shane, Citation2017). Non-normative ethics has been proposed in ICE (see Simpson & Dervin, Citation2019b, Citation2020) insofar that the self refrains from imposing their values and beliefs onto the other, and vice versa. The non-normative ethics of the act postupok functions as an important negotiating space allowing the self and other to problematise and contest the ground though which truth pravda will be co-constructed and co-created (Marjanovic-Shane & White, Citation2014). I also argue that this conceptualisation of truth in Intercultural Communication Education will avoid the pitfalls of post-truth and the conceptual inertia of non-essentialism. This dialogical approach to truth means that through the subject’s “non-alibi in being” the subject cannot be voiceless, e.g., the subject cannot hide behind the belief that they are not going to stereotype or label (which often characterises non-essentialist approaches to ICE), instead, the construction of the ethical act postupok is essential in revealing multiple voices (e.g., different ideologies, different perspectives and the diversity of intersubjectivities) which are required to construct the being-event bytie-sobytie (Bakhtin, Citation1993, 2012). In this sense, ICE should not function through the aim of ‘successful communication’ or the obtainment of certain facts or truths (in the sense of intercultural competencies), on the contrary, ICE should acknowledge that the self and other having multiple different voices (in which disagreements and debates are essential) in playing an integral function in the construction of co-being so-bytie. It is precisely the different intersubjectivities found within acts of co-being which constitutes the construction of non-normative knowledge and truth.

Conclusion: Dialogism as a practice to counter epistemic injustice in Intercultural Communication Education?

Inspired by Mikhail Bakhtin (Citation1993, 2012) this paper has put forward a dialogical and non-normative perspective of truth for Intercultural Communication Education (ICE). This conceptual paper has addressed the following research question: To what extent can a dialogical approach to truth address and redress epistemic power imbalances in ICE? The paper has conceptually mapped the problems of epistemic power imbalances in ICE and has offered a dialogical approach underpinned by non-normativity to break with the binary of truth and post-truth in ICE. The paper criticises both essentialist approaches and non-essentialist approaches in ICE insofar that both perspectives either fall into the epistemic essentialism of normativity and/or the hyper-relativity of non-essentialism.

The dialogical approach proposed in this paper is situated in response to normative conceptualisations of truth in ICE and is also a response to the hyper-relative inertia found within non-essentialist approaches to ICE (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). Here, the doxa that one must respect the other and that one must tolerate the other is deeply problematic as it often reinforces cultural differences which can serve to bias and prejudice the other (Simpson, Citation2020). Conceptually the paper situates truth as, ‘true knowledge is never ‘purely’ objective or ‘merely’ subjective’, but always both at the same time (Schindler, Citation2020, p. 377). There is a likeness in Schindler’s conceptualisation of truth and Bakhtin’s approach insofar that there is an in-betweeness, between notions of normative objectivity and post-truth hyper-relativity where truth[s] should be continuously problematised through a dialogical non-normative approach (Simpson & Dervin, Citation2020).

This conceptual paper on truth in ICE is pertinent given the current debates surrounding epistemic injustice (R’boul, Citation2022) and epistemic power imbalances in terms of how knowledge is constructed (R’boul, Citation2021) as part of wider discussions on decolonialisation (Aman, Citation2017). In previous publications (Simpson & Dervin, Citation2019a; Simpson & Dervin, Citation2020) I have argued that ICE remains predominantly Anglophone and ‘Western-centric’ (I do not use this term to reproduce the binaries of ‘West’ and ‘East’ but as a reflection of how knowledge is often conceptualised through ‘Western’ thought and philosophies). Conceptually and practically, this raises several issues in terms of who is really voicing their perspectives in ICE, who remains silenced, notwithstanding the fact that scholars may feel the need to orientate themselves towards, or that they have to use, Anglophone or ‘Western-centric’ perspectives to legitimise their epistemic knowledge (Simpson et al., Citation2022).

A Bakhtinian approach to truth, through the emphasis on dialogue and non-normative ethics, can help to enrich scholarship in ICE through focusing on the dynamic actioning of participating thought (Bakhtin, Citation1993). In this sense, truth retains the epistemological function of questioning “what is…” whilst simultaneously actioning the reflexive function of the act postupok (i.e., the steps taken) (Bakhtin, Citation1993). Thus, scholars/educators/practitioners in ICE should continually ask “what is…” whilst opening the interanimation of multiple intersubjectivities through acts postupok which constantly (and critically) question how did one reach an understanding, and/or, how did one reach no understanding (and why?) (Dervin & Simpson, Citation2021). This movement involves critically questioning all epistemic assumptions, beliefs, values, concepts and practices associated with ICE.

Finally, as part of the conceptual model presented the notion ‘non-alibi in Being’ means that the self and other can never be voiceless in the act postupok. In redressing epistemic power imbalances the dialogical relationship between istina (epistemological truth) and pravda (truth in Justice) can be used to enable multiple voices and multiple perspectives in ICE meaning that truth (and knowledge) should always be problematised from non-normative perspectives. One way this can be done through digging into the social lives of concepts (Hann, Citation2016) in analysing the etymologies of notions in different languages to enrich theory and practice in ICE by finding alternative means to address and redress power across concepts, theories and practices.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ashley Simpson

Dr Ashley Simpson is Lecturer in Language Education at The University of Edinburgh, UK. Simpson specialises in Intercultural Communication Education and is the Programme Director of MSc Language and Intercultural Communication. Simpson also holds a Visiting Professorship from Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, School of Language, Literature and Law.

References

- Aman, R. (2017). Decolonising intercultural education: Colonial differences, the geopolitics of knowledge, and inter-epistemic dialogue. Routledge.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1993). Toward a philosophy of the act. University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (2012). Sobranie sochinenij. (T.3). In S. G. Bocharov & V. V. Kozhinov (Eds.), Teoriia romana (1930–1961 gg.) (pp. 6–877). Jazyki slavianskikh kul’tur.

- Berdyaev, N. (1962). Truth and revelation. Collier Books.

- Brandist, C. (2002). The Bakhtin Circle: Philosophy, culture and politics. Pluto Press.

- Brandist, C. (2015). Introduction: the ‘Bakhtin Circle’ in its own time and ours. Studies in East European Thought, 67(3–4), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11212-015-9234-5

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Cassin, B., Apter, E., Lezra, J., & Wood, M. (Eds.). (2014). Dictionary of untranslatables: A philosophical lexicon. Princeton University Press.

- Chandler, D., & Munday, R. (2020). A dictionary of media and communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 Jul 2022, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198841838.001.0001/acref-9780198841838.

- Dasli, M. (2019). UNESCO guidelines on intercultural education: a deconstructive reading. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2018.1451913

- Dasli, M., & Diaz, A. R. (Eds.). (2017). The critical turn in language and intercultural communication pedagogy: Theory, research and practice. Routledge.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Implementing intercultural competence assessment. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 477–491). Sage.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2019). Manual for developing intercultural competencies: Story circles. Routledge.

- Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: A theoretical and methodological toolbox. Springer.

- Dervin, F., & Simpson, A. (2021). Interculturality and the political within education. London: Routledge.

- Dervin, F., & Tournebise, C. (2013). Turbulence in intercultural communication education (ICE): Does it affect higher education? Intercultural Education, 24(6), 532–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2013.866935

- Esposito, R. (2012). The third person: Politics of life and philosophy of impersonal. Polity.

- Etymonline. (2022). Truth. Retrieved January 23, 2022, from. https://www.etymonline.com/word/truth#etymonline_v_17903

- Ferri, G. (2018). Intercultural communication: Critical approaches and future challenges. Springer.

- Ferri, G. (2020). Difference, becoming and rhizomatic subjectivities beyond ‘otherness’. A posthuman framework for intercultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(5), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1774598

- Ferri, G. (2022). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house: decolonising intercultural communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(3), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2022.2046019

- Florensky, P. (2018). The pillar and ground of the truth: An essay in orthodox theodicy in twelve letters. Princeton University Press.

- Foucault, M. (2010). The birth of biopolitics. Lectures at the College de France, 1978–1979. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hall, E. T. (1959). The silent language. Anchor Books.

- Hann, C. (2016). A concept of Eurasia. Current Anthropology, 57(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1086/684625

- Hirschkop, K. (1998). Bakhtin myths, or, why we all need alibis. The South Atlantic Quarterly, 97(3), 579–598. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/bakhtin-myths-why-we-all-need-alibis/docview/197296861/se-2?accountid=10673

- Hirschkop, K. (2021). The Cambridge introduction to Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoff, H. E. (2014). A critical discussion of Byram’s model of intercultural communicative competence in the light of bildung theories. Intercultural Education, 25(6), 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2014.992112

- Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication & ideology. Sage.

- Holliday, A., & MacDonald, M. N. (2020). Researching the intercultural: Intersubjectivity and the problem with postpositivism. Applied Linguistics, 41(5), 621–639. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz006

- Lyotard, J. F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. University of Minnesota Press.

- MacDonald, M. N., & O’Regan, J. P. (2013). The ethics of intercultural communication. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(10), 1005–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00833.x

- Marchenkov, V. L. (2021). Nikolai Berdyaev’s philosophy of creativity as a revolt against the modern worldview. In M. F. Bykova, M. N. Forster, & L. Steiner (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of Russian thought (pp. 217–238). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62982-3_11

- Marjanovic-Shane, A., & White, E. J. (2014). When the footlights are off: A Bakhtinian interrogation of play as postupok. International Journal of Play, 3(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2014.931686

- Matusov, E., & Marjanovic-Shane, A. (2017). Many faces of the concept of culture (and education). Culture & Psychology, 23(3), 309–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X16655460

- Meeuwis, M. (1994). Leniency and testiness in intercultural communication: Remarks on ideology and context in interactional sociolinguistics. Pragmatics, 4(3), 391–408.

- Min, E. (2001). Bakhtinian perspectives for the study of intercultural communication. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 22(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860120037382

- Nally, D. (2021). Post-truth, education and dissent. Educational Philosophy and Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.2000389

- Peters, M. A. (2017). Education in a post-truth world. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(6), 563–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1264114

- Peters, M. A., Jandrić, P., Fuller, S., Means, A. J., Rider, S., Lăzăroiu, G., Hayes, S., Misiaszek, G. W., Tesar, M., McLaren, P., & Barnett, R. (2022). Public intellectuals in the age of viral modernity: An EPAT collective writing project. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(6), 783–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.2010543

- Phillips, A. (2009). Multiculturalism without culture. Princeton University Press.

- R’boul, H. (2021). North/South imbalances in intercultural communication education. Language and Intercultural Communication, 21(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1866593

- R’boul, H. (2022). Postcolonial interventions in intercultural communication knowledge: Meta-intercultural ontologies, decolonial knowledges and epistemological polylogue. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 15(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2020.1829676

- Rendall, S, (2014). Culture. In B. Cassin, E. Apter, J. Lezra, & M. Wood (Eds.), Dictionary of untranslatables: A philosophical lexicon (p. 191). Princeton University Press.

- Schindler, S. (2020). The task of critique in times of post-truth politics. Review of International Studies, 46(3), 376–394. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210520000091

- Simpson, A. (2020). ‘I with an [other]’, otherness and discourse: Reconstructing ‘democracy’ through intercultural education?. In F. Dervin, R. Moloney, & A. Simpson (Eds.), Intercultural competence in the work of teachers: Confronting ideologies and practices, (pp. 42–56). London: Routledge.

- Simpson, A., & Dervin, F. (2017). ‘Democracy’ in education: An omnipresent yet distanced ‘other’. Palgrave Communications, 3(24), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0012-5

- Simpson, A., & Dervin, F. (2019a). Global and intercultural competences for whom? By whom? For what purpose? An example from the Asia Society and the OECD’. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(4), 672–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1586194

- Simpson, A., & Dervin, F. (2019b). The Council of Europe Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture: Ideological refractions, othering and obedient politics. Intercultural Communication Education, 2(3), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.29140/ice.v2n3.168

- Simpson, A., & Dervin, F. (2020). Forms of dialogism in the council of Europe reference framework on competences for democratic culture. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 41(4), 305–319.

- Simpson, A., Dervin, F., & Tao, J. (2022). Business English students’ multifaceted and contradictory perceptions of intercultural communication education (ICE) at a Chinese University. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(6), 2041–2057.

- Solovyov, V. S. (1965). Foundations of theoretical philosophy (V. Tolley & J. P. Scanlan, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.

- Tihanov, G. (2021). Bakhtin, translation, world literature. In M. F. Bykova, M. N. Forster, & L. Steiner (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of Russian thought (pp. 659–671). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62982-3_30

- Vasylchenko, A. (2014a). Postupok. In B. Cassin, E. Apter, J. Lezra, & M. Wood (Eds.), Dictionary of untranslatables: A philosophical lexicon (pp. 811–812). Princeton University Press.

- Vasylchenko, A. (2014b). Svoboda. In B. Cassin, E. Apter, J. Lezra, & M. Wood (Eds.), Dictionary of untranslatables: A philosophical lexicon (pp. 1105–1108). Princeton University Press.

- Vasylchenko, A. (2014c). Istina. In B. Cassin, E. Apter, J. Lezra, & M. Wood (Eds.), Dictionary of untranslatables: A philosophical lexicon (pp. 513–515). Princeton University Press.

- Xu, K. (2013). Theorizing difference in intercultural communication: A critical dialogic perspective. Communication Monographs, 80(3), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2013.788250

- Zembylas, M. (2022). Affirmative critique as a practice of responding to the impasse between post-truth and negative critique: pedagogical implications for schools. Critical Studies in Education, 63(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1723666