?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Dual vocational education and training (VET) has recently been introduced in Catalonia, as in the whole of Spain, and it should be the only VET system in the near future. However, Dual VET still coexists with traditional VET. The former has much more on-the-job training, companies are more involved in curricula design and training management, and trainees receive a salary or a scholarship. This study analysed the effect of Dual VET on students’ grades and degree completion. We use the whole population of Catalan students during four academic years (from 2015–2016 to 2018–2019) that completed their degree. We employ an instrumental variable approach to explain grades at completion. Results show that Dual VET had a positive effect on grades irrespective of the method and outcome used (standardised or non-standardised grades). In fact, our instrumental variables estimation showed a greater impact than the ordinary least squares results. In addition, Dual VET also increased the probability of graduation. Thus, the transformation of the Catalan VET into a Dual VET may have positive effects, since the latter improves course completion and grades.

Introduction

Dual VET has recently been introduced in Spain over a short period of time. It has been implemented since 2012 on a voluntary basis for schools and students, and this has generated a wide roll-out of the model in all productive sectors and Spanish regions. Notwithstanding this, Dual VET still coexists with “traditional” VET (in Spain, it means school-based VET with a limited amount of training at company level), which is still followed by most VET students. A new VET law was approved in December 2021, and it is currently being processed at Spanish Parliament; this law foresees that Dual VET will be mandatory in all VET studies, including training in firms from 25% to 50% of the total duration of training.

The advantages of Dual VET for all its stakeholders, i.e. students, schools, companies, and the economy, are well known (Euler, Citation2013; Jansen & Pineda-Herrero, Citation2019). Positive results of Dual VET have been identified in Spain and also in other countries, especially in Europe, such as Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, the United Kingdom and France, among others (Cedefop, Citation2019). However, analyses of the academic effectiveness of the model are scarce. Therefore, given this scenario, we propose two hypotheses:

Dual VET model increases students’ degree completion compared to school-based VET.

Dual VET allows students to get a higher average grade with regards to school-based VET.

The analysis is carried out using regression techniques that allow differentiating the effect of taking Dual VET with respect to the school-based VET. This study aimed to answer this question by analysing the academic performance data of young people in Catalonia (Spain) who were enrolled in Dual VET compared to those who enrolled in school-based VET. These results can provide some information for decision-making on the implementation of the new Bill and, thus, increase the effectiveness of this track of the education system.

We contributed to the previous literature in three ways. First, we analysed the effect of Dual VET on the grades obtained by the students as well as on degree completion. As it is shown in the next section, some studies have analysed the effect on degree completion of different types of VET (including comparisons with the academic track), but to the best of our knowledge this was the first attempt to analyse the effect of Dual VET on VET grades. This was possible, since in Catalonia a Dual VET system is being implemented while the “traditional” one still exists; this is one of the reasons to choose this territory to apply the study, together with more reasons explained latter. Thus, since the pioneering study of Coleman et al. (Citation1966), it is common to analyse the effects of several variables on grades and on degree completion, such as those related to the student, teachers, peers, and school characteristics, among others, but this is the first study to consider the effect of Dual VET. Therefore, the effects of Dual VET on grades and graduation may show the efficiency of this system compared to the traditional VET one. Second, it should be highlighted that we did not consider a sample of students but the whole population of Catalan students during four academic years (from 2015–2016 to 2018–2019). Moreover, the data came from student and school level. Finally, in our regression analysis, we controlled for sample selection bias, which is not so common in VET-related studies.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section describes the research evidence regarding Dual and traditional VET with regards to academic education and the labour market. Then, the Catalan VET system is described as well as the database and the econometric strategy implemented. Finally, the empirical results, and a final discussion and conclusions section are presented.

Literature review

The Dual VET system has a long tradition in Germany, and in countries such as Austria, Switzerland, and Denmark, with a high volume of enrolled students and strong cooperation between the educational and productive systems – see a description in Fürstenau et al. (Citation2014) – as well as its potential export capacity (Euler, Citation2013). There is an ongoing discussion on whether Dual VET based on the German model can be readily transferred to other countries (Euler, Citation2013; Gessler, Citation2017). Obviously, it is not a matter of transferring the system wholesale from one country to another, the mistakes in this regard being already known, but the desirable approach is to introduce some characteristics of the other system at the local level so that students and employers regard the change as attractive (Valiente & Scandurra, Citation2017).

Furthermore, it must not be forgotten that the Dual system is very demanding in terms of requiring that companies must be able to provide a stable offering of training opportunities of sufficient magnitude (Juul & Jørgensen, Citation2011); for the best results in this regard, companies have to be big, which is difficult in the case of Spain (and Catalonia), compared, for example, with Germany (Bentolila & Jansen, Citation2019). Nevertheless, Pineda-Herrero et al. (Citation2015) and Jansen and Pineda-Herrero (Citation2019) showed that the size of companies is not as important for VET as is their real impact. Thus, their results highlighted the fact that small companies with a strong VET motivation offer better learning opportunities and more efficient apprenticeships in terms of employers’ and students’ satisfaction. South European Countries, such as France, Portugal and Italy, have similar conditions to develop Dual VET, and the model based on the educational centre in common; so they can share the efficacy strategies learned in Northern Europe (Cedefop, Citation2019).

There is a vast body of literature on the determinants of school grades and completion (see Hanushek & Woessmann, Citation2010) and skills development (Scandurra & Calero, Citation2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of analysis with regards to the effect of taking part in the Dual VET system on the marks obtained in vocational education. In addition, we also considered the effect of receiving dual training on completing a vocational degree (some existing evidence on this topic is presented). Usually, it is not possible to analyse the role of Dual VET compared to other VET systems, because vocational training systems are mainly either dual or non-dual (although some school-based VET systems have included some training courses at companies). Thus, in this section we consider the effects of the dual system (or workplace training) on school completion as well as on other topics, so we can have a more complete picture of the benefits of having a Dual VET system.

With regards to school completion, using panel data following a cohort for over 10 years in the Canton of Geneva, Switzerland, Latina (Citation2017) showed that a transition from school-based to Dual VET (within commercial VET) increased students’ chances of earning a qualification (although students changing modes lose half a year in the process). It matters whether the dual system increases school completion since Campolieti et al. (Citation2010) showed that dropouts have poorer wage and employment outcomes, and they do not make up for their lack of education through additional skill acquisition and training. In addition, Scholten and Tieben (Citation2017) showed that, in Germany, pre-tertiary vocational qualifications do serve as a safety net in cases where students drop out of higher education, compared to those from an academic track, because vocational education helps students to enter the labour market more easily. In their review of 1250 policy evaluations from the United Kingdom and other OECD countries, the analysis of the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth (Citation2015) shows that there is some evidence that apprenticeships improve skill levels and stimulate further training.

Thus, Dual VET seems like a good formative path for finishing studies and moving on. In this regard, as Bishop and Mane (Citation2004) and Meer (Citation2007) showed for the United States, it is positive for school completion to have a VET background. This result was also reported for completing secondary school as well as post-school VET courses (but not academic higher education) by Polidano and Tabasso (Citation2014) for Australia. They also found a higher effect when VET contained workplace learning or apprenticeship. In fact, the OECD (Citation2010) has claimed that apprenticeships and the use of workplace learning in classroom-based VET programmes help to develop work-relevant skills that cannot be learnt in the classroom. Bishop and Mane (Citation2004) claimed, after using cross-country comparisons, that countries with higher rates of VET participation have higher rates of school completion.

With regards to the labour market, one of the traditionally best-known positive effects of Dual VET is that it favours the school-to-work transition of young people, since it matches students more closely to jobs (Ryan, Citation2001). Thus, dual training countries, such as Denmark, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland are among the OECD countries with the lowest unemployment rates for youth. Moreover, Austria, Denmark, and Germany are among the countries with the lowest share of youth experiencing multiple periods of unemployment (Quintini et al., Citation2007). Likewise, it should be taken into consideration that an early entry into the labour market is particularly important, since it may develop employment competences in young people and increase their employability and future promotions (Rowe & Zegwaard, Citation2017; Weisshaar & Cabello-Hutt, Citation2020). This close relationship between the dual system and labour integration of the youth is also reported in Bol and Van de Werfhorst (Citation2013) and Brunetti and Corsini (Citation2019). For Spain, Bentolila and Jansen (Citation2019) showed that, in Madrid, the newly introduced Dual VET system improved job placement compared to the traditional VET.

In addition, Van der Velden et al. (Citation2001) showed that European countries with apprenticeship systems enjoy better youth employment patterns, particularly in terms of larger employment shares in skilled occupations and in high-wage sectors. In his analysis of 12 European countries, Gangl (Citation2003) concluded that apprenticeships in the dual system have higher returns to education when compared to school-based education. Likewise, Shaw (Citation2012) showed that upper-secondary VET diplomas improve labour market outcomes after higher education in the United Kingdom. As Steedman (Citation2005) pointed out, part of this positive effect of VET may come through a better matching of training to labour market demand that results from apprenticeship training. Examining companies’ recruitment policies in three sectors in Germany, Switzerland, and England, Hippach-Schneider et al. (Citation2012) showed that academic graduates are not preferred to those completing initial VET.

If Dual VET is compared to traditional VET, in Catalonia, CTESC (Citation2017) shows that the labour insertion of the dual system graduates is higher (70%) than the average of traditional VET graduates (50%), and it also allows for a higher salary level among graduates. In addition, firms identify many advantages of employing graduates from Dual VET rather than other graduates, mainly because the apprentices are a better fit for the firm, and they have better professional competences (Jansen & Pineda-Herrero, Citation2019). As Bentolila and Jansen (Citation2019) reported, from a review of different European countries, the benefits of Dual VET are particularly important if students who completed dual training are compared with those who leave their studies without obtaining a VET or a post-compulsory secondary education qualification. Furthermore, Polidano and Tabasso (Citation2014) showed that labour market outcomes improve if VET includes a short workplace learning component. Finally, comparing classroom-based VET with workplace learning, Polidano and Tabasso (Citation2014) also showed the latter to increase the chances of being in a career job with higher earnings.

However, this traditional positive evaluation of VET has been challenged in recent studies. Thus, using micro-data from the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) for 18 countries, Hanushek et al. (Citation2011) concluded that the relative labour market advantage of vocational education decreased with age. The main reason is that vocational (“skill-based”) as opposed to general (“concept-based”) education leads to slower adoption of new technologies. As Neyt et al. (Citation2020) argued, the advantage when entering the labour market might decrease over time due to two reasons: on the one hand, the obsolescence of occupation-specific skills acquired in vocational education; on the other hand, the lesser development of cognitive skills, problem solving, and critical thinking. Thus, Neyt et al. (Citation2020) showed that recent studies have found empirical evidence for this trade-off between the short-term advantages and the long-term disadvantages of vocational education on the labour market, and that the effects of vocational education ultimately may even turn negative. In this context, Agarwal et al. (Citation2019) pointed out that Italian college graduates with a VET background are more likely to find their first job quickly after school completion than other graduates, but that VET negatively impacts wages and that these graduates are less likely to fill highly ranked occupations. In addition, it has been pointed out that VET students’ lack of mobility after their first job may have persistent negative effects on employment probabilities and wages later in life (Häkkinen, Citation2006; Low et al., Citation2010).

Neyt et al. (Citation2020) pointed out that several studies reported no evidence of such a trade-off, so that vocational education does not lead to different long-term labour market outcomes compared to general education. As Polidano and Tabasso (Citation2014) showed for Australia, compared to academic education, VET had no effect on being employed (although it favours transitions to full-time work). In addition, Bentolila and Jansen (Citation2019) pointed out that the evidence regarding differences in wages between VET graduates and Dual VET graduates is not conclusive. In this matter, Brunello and Rocco (Citation2017) refuted the claim that the short-term advantage of vocational versus academic education (in terms of school-to-work transition) has a trade-off with long-term disadvantages, which are lower employment and/or lower wages. Thus, using data based on the careers of people born in the United Kingdom in 1958, they found evidence of a trade-off, but only for real wages and only for the group with lower vocational education. Likewise, these results were confirmed when the careers of people born in 1970 were examined. Consequently, the evidence is not conclusive on this matter.

In addition, Neyt et al. (Citation2020) pointed out that most studies did not control for unobservable differences between students who opt for vocational education and students who do not. Therefore, the results are questionable, since they have an omitted variable bias, distorting the true impact of vocational education on labour market outcomes.

Beyond this micro-level analysis of the relationship between VET and the labour market, other studies have analysed the effects of VET on the economy, considering a macro-level perspective. Thus, Ashton and Green (Citation1996) and Boyer and Caroli (Citation1993) showed the positive effect of vocational dual training systems on productivity and economic growth.

Finally, although the literature shows the positive effects of Dual VET systems on school completion, and it seems that VET has a positive effect on school-to-work transition, and maybe throughout the graduate’s work experience, other less desirable effects of the Dual VET system have to be considered in order not to be reproduced when it is implemented in other countries, such as the traditional high level of social stratification (Altreiter, Citation2021; Protsch & Solga, Citation2016).

Vocational education and training in Catalonia

In Catalonia, there are different types of vocational studies: initial vocational training (known as VET in most countries), training for employment, and continuous vocational training. The former corresponds to the educational field. It is organised in areas of study or professional families and trains students to develop a profession. The vocational education system has two academic levels: medium VET (ciclos formativos de grado medio) in post-secondary education (after 16 years old) as an alternative to Baccalaureate, equivalent to vocational education and training (VET); and high VET (ciclos formativos de grado superior) as a continuation of medium VET or after Baccalaureate as a professional track, equivalent to the certificate of higher education (HNC). Dual Training is available at both levels. For more information about the Spanish education system, see Eurydice (Citation2022) and MEFP (Citation2022).

The most frequent situation is that, once students have finished compulsory education (named education secundaria obligatoria, ESO) around the age of 16, they can continue the academic path (bachillerato, equivalent to General Certificate of Education GCE) or the professional path (ciclos formativos de grado medio or VET). Once they finish GCE, they can access higher education, that is, university or the ciclos formativos de grado superior (HNC). Likewise, access to the HNC through VET is guaranteed if you successfully complete an entrance exam or the required preparatory course. Students who do not finish ESO can access training and insertion programmes (PFI in Spanish), which are an opportunity to re-enter the educational system or acquire the essential knowledge to access the job market. The duration of the VET and HNC is, in general, two academic years. Thus, while VET is part of the secondary education system, HNC configures higher education together with university studies.

It should be noted that Catalonia has made a commitment to incorporate Dual VET into its vocational training system, since the creation of the Dual VET model in 2012. Due to this commitment, Catalonia is one of the Autonomous Communities leading Dual VET in Spain, (Pineda-Herrero et al., Citation2019), with an important increase of enrolments during the last 10 years: going from almost 600 Dual Vet students in 2012 to more than 9000 in 2020 (De, Citation2021). This is why it is worth analyzing its impact. This change in the VET model has occurred in a context in which vocational training in general, and the Dual VET system in particular, have been increasingly valued in Spain. This higher consideration of Dual VET has already happened previously in other countries, following the North and Central European tradition (see Hyland, Citation2002).

In Spain, the Royal Decree 1529, approved in 2012, regulates the implementation of the Dual VET model in all the country; each Autonomous Community implements this law in its territory, with important differences between them. In Catalonia, the Autonomous Law 284/2011, rules the development of VET training and the basis of Dual VET in this territory (see Gencat, Citation2022). A new Spanish VET law has just been approved, and it extends Dual VET to all professional training in the country. The law – Proyecto de ley orgánica de Ordenación e Integración de la Formación Profesional Dual – is now in the Parliament process, but its development will take some time since there are a lot of agents and interests involved.

In Catalonia, over the academic year 2019–2020, the number of students enrolled in VET was 71,146 (43.0% were women) and in HNC it was 91,086 (50.5% were women). GCE that year was the option for 94,437 students (Gencat, Citation2020). That is, the ratio was 1.32 choosing GCE compared to VET once they finished ESO. In previous decades, this ratio was even larger (1.87 and 2.52 a decade and two decades ago, respectively). It is well known that in Spain vocational training is less preferred and that is especially the case of VET compared to HNC. Indeed, the number of students attending HNC is greater than the ones enrolled in VET.

Spanish (and Catalan) Dual VET is a vocational training modality where students become apprentices and combine lectures in the school centre with labour activity at a firm. Apprentices spend part of their time at a vocational school and another part at the training company. In contrast to the traditional model, called FCT (formación en centro de trabajo or training in work centre), where firms provide internships for 2–3 months, in Dual VET the apprentice spends at least 33% of the total training time at the training firm and alternates between the vocational school and the training firm. This mode involves a much higher degree of engagement by firms in the training process, and provides some benefits for the students, the vocational schools, and the firms (Grollmann et al., Citation2017; Jansen & Pfeifer, Citation2017).

The agreement between a Dual VET student and a firm is formalised by means of a labour contract or a scholarship training agreement. Both situations imply that the student is registered with Social Security and will consequently have a work activity. The contract is allowed for students up to 30 years old, with a duration of 1–3 years, and it makes provision for a 40-hour workweek, including the training lectures at the school centre. In the first year, a minimum of 25% of the working days should be at the firm. These contracts are promoted through benefits from Social Security (firms do not pay the social security contributions), and the apprentice earns at least the interprofessional minimum wage. In the case of internships, the firm manages the registration of the scholarship holder with Social Security and pays the contributions. The minimum period in an academic year, which can be extended, is 2 months, and the maximum is 10 months. Most students spend 3–5 months in the firm throughout the academic year.

Dual VET is not just about doing an internship in a company (these are also available in traditional vocational studies through FCT schemes). Instead, there is a greater interaction between the educational and productive systems. Thus, companies must train the student and evaluate the learning, following the training agreement with the educational centre. Likewise, a committee to monitor the agreement is set up to supervise and coordinate the actions to be carried out. The company has to appoint a mentor for the apprentice during their stay in the company (Bentolila & Jansen, Citation2019). However, how the new system is implemented will determine whether Dual VET really distances itself from the school-based model.

In 2019, around 6000 firms and 295 training centres participated in Dual VET in Catalonia (Gencat, Citation2021). These figures were 2500 and 171, respectively, in 2016. Despite the benefits of the contract or salary payment modality, many of the firms (81%) chose the scholarship modality; one of the reasons is the administrative complexity of the contract (CTESC, Citation2017). In this sense, satisfaction with Dual VET is overwhelming both at the level of educational centres as well as students and companies (CTESC, Citation2017; Mora, Citation2021).

Data

The dataset used in this study corresponds to 495,625 observations about the whole population of 263,487 students attending vocational studies in Catalonia in the academic years 2015-2016, 2016-2017, 2017-2018, and 2018-2019. Thus, it has to be highlighted that the analysis is based on the whole population. Students were conveniently anonymised and linked to school centre codes (457 training centres). In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, the following variables were available: gender, date of birth, and nationality. Besides the level within a degree and its code that determines whether it is a VET or an HNC degree, we also knew the area of study of each degree (there are 177 belonging to 24 areas). We grouped those degrees that were collapsed or absorbed by new ones together. The data also told us whether teaching took place face-to-face, blended, or online.

To explain grades, we used information related to students and school centres. Once students have finished their degree (VET or HNC), they are graded. For this reason, we only have information on qualifications for 46.8% (101,891 out of 217,921 students), given that the rest of the data set corresponds to enrolling characteristics in previous academic years. Obviously, we did not consider those students who were only present in the last academic year and were enrolled in the first year of a degree. Based on that, we were able to identify students that failed to pass the course and, therefore, had to repeat an academic year.

For school centres, we used two complementary datasets provided by the Statistical Institute of Catalonia (IDESCAT) and the Education Department of the regional government of Catalonia. These files contained several characteristics: centre code, municipality and physical address, type of studies offered, and the nature of the school’s ownership (public, vouchered, and private).

Considering that we only observed students’ grades after they had obtained their qualification, since we are using administrative data, the average grade was 7.04 (on a 0–10 scale), with a median of 6.96 and a standard deviation of 0.98. depicts the overall student characteristics for the final dataset considering unique students. As is shown, 46% were female, 88% had Spanish nationality, and course repeaters represented 26%. Access was predominately from ESO (for VET) and high school (for HNC) and most were in the face-to-face teaching modality. The average age was 23.4. There is no limit for entrance to VET and HNC. However, the educational system establishes VET after finishing compulsory education (at age 16) and HNC after finishing high school (at age 18). Those at HNC were the most (61%), while Dual VET was an option for 8% of students. Most students were enrolled in a public training centre. ICT, health, and sociocultural services were the most frequent families of selected degrees. Unsurprisingly, Barcelona city had the highest number of students. In addition, in the appendix shows students’ characteristics not only for the overall population but also for those students on Dual VET and on “traditional” VET separately. Some differences may be observed regarding gender, if the student has repeated a course, the type and level of education, subject family, and academic year.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics.

Empirical strategy

Information on grades was available only for those who had completed a course. Thus, grades are influenced by whether the course was completed as part of VET or HNC. Therefore, in the analysis of grades (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ), we had to include a selection equation to explain subject achievement (EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) ). For this purpose, we needed an exclusion restriction, that is, a variable that influenced course achievement but not qualification. Fortunately, not all the courses were available for enrolment over the four academic years. Some were initiated during this period because of firms’ demands, and others were eliminated because they were outdated. Data mining involved linking old courses (under the “LOGSE” law) to new ones (ruled by the “LOE” law)Footnote1 based on a possible continuity. Indeed, although 97.7% were optional during the four academic years, the rest lasted from one to three academic years.

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) Yi indicates the grades of student I on a 0–10 scale, Xi is a list of variables at student level (gender, age, nationality, quarter of birth, repeater condition, access route to the degree, and teaching modality). We also considered within Xi those characteristics related to the academic year, the kind of degree (VET or HNC) and, alternatively, the area of study or even the specific degree. ci represents the characteristics at school centre level, i.e. the ownership nature or the territorial service that the centre belongs to, whereas duali represents Dual VET. Ti indicates having achieved the degree. It depends on the individual characteristics that influence degree achievement (gender, quarter of birth, Dual VET, access route, school centre’s ownership, and area of study) and the exclusion restriction that corresponds to the number of academic years that the degree was available (nci) (see EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) ). Finally, usual error terms were considered (ϵi and ui).

A further econometric challenge was endogeneity in Dual VET. Besides unobservable variables, in some cases school centres select students enrolled in Dual VET based on previous academic achievement during the first year of the degree. In other cases, school centres select Dual VET students with low achievement to motivate them and to improve their learning opportunities (Jansen & Pineda-Herrero, Citation2019). That is, reverse causality would be present. The solution was to estimate by means of instrumental variables (IV) (see EquationEquation 3(3)

(3) ). For this purpose, we needed a variable that had to be related to the probability of being enrolled in Dual VET but that did not have an influence on academic achievement. The chosen variable corresponds to the availability supply of Dual VET not far from the centre in which the student completed his/her degree. The higher the percentage of centres offering this option the greater the probability to select this modality. Specifically, we computed this probability of being enrolled in Dual VET by academic year considering any school centre located within 5 km from the centre where the student had previously been enrolled. For this reason, we searched for the geographic coordinates and computed the distance between all school centres. It has to be highlighted that our instrument is unrelated to our outcome (VET grades) except through Dual VET participation. Thus, Catalan students choose field of study and to be enrolled in Dual VET without considering grades. The reason is that there is no previous public information on average grades by school centre. EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) considers those factors that influence the probability of being enrolled in Dual VET.

(3)

(3) The IV in EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) , that is, the probability of being enrolled in Dual VET within a 5 km distance from the selected centre is represented by ddi. The usual error term was considered (vi).

In the econometric model, we included students’ personal characteristics as well as a significant number of variables related to schools and the educational process to analyse students’ degree completion and grades. Personal characteristics refer to gender, age and quarter of birth, immigrant status as well as if student is experiencing grade repetition (a repeater). Several studies have shown the importance of considering these factors (Hanushek & Woessmann, Citation2011; Morrison & No, Citation2007; Robertson, Citation2011). School inputs are usually introduced in the analysis of the education production function (Dronkers & Robert, Citation2008; Hanushek & Woessmann, Citation2011). In our study we considered data available on the way students entered VET (access to degree), the type of VET, ownership of the school (private, vouchered or public), area of study, school localisation, and academic year.

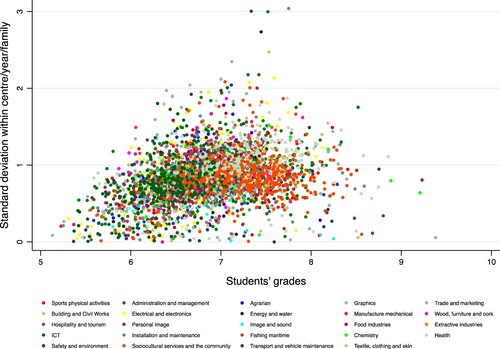

A further step was analysing the determinants of grades in levels or conveniently standardising them, since qualification criteria are very heterogeneous based on the specific school centre and the area of study that the degree belongs to. For this purpose, we standardised grades within centre/family/academic year but only considering those degrees that had at least 10 students per training centre. Estimations based on grades in levels can be interpreted straight. We considered this latter approach for robustness reasons but also because grades are not strictly comparable across centres. shows how heterogeneous the grading patterns are across the 24 areas of study and the training centres. Likewise, some combinations from the same area of study display a higher standard deviation than others.

Results

shows the marginal effects for the selection equation (EquationEquation 2(2)

(2) ), which in turn shows the results of the effect of Dual VET on completing a degree. Although we did not place an emphasis on the selection equation, we have to report that the lambda value for this equation was 0.3 and was statistically significant (p < 0.005). Likewise, our instrument introduced in EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) turned out to be statistically significant and the first stage showed an overall significance (Wald = 12,531.43, p < 0.000). Controlling for personal, area of study, and school data, it is worth noting that Dual VET had a positive effect on the probability of completing the degree. Indeed, when computing marginal effects, Dual VET increased degree completion by 1.77 points, which represented 3.88 times the average value of the IV. With respect to other educational variables, online and blended teaching had a negative correlation with the achievement of the cycle. Compared to public schools, students from private schools were less likely to complete the cycle, but those from vouchered schools were more likely to graduate. Finally, students in the higher levels of vocational education (HNC) had a higher probability to graduate than those in the lower levels (VET).

Table 2. Degree achievement: Heckman first stage results marginal effects.

reports the marginal effects related to the impact of Dual VET on academic qualifications. Column (1) shows the OLS results only accounting for selection, whereas Columns (2) and (3) indicate the results obtained through the use of an IV approach. Indeed, the second column shows the estimation marginal effects of Dual VET on grades in levels. Moreover, the third column indicates the effect of Dual VET after standardising grades at each training centre and degree/academic year. Appendix 1 lists all the marginal effects for the results explaining grades (). Our results indicate that Dual VET had an influence, irrespective of the method and outcome used, although the IV estimation method depicts a greater impact than the OLS results. In fact, Dual VET increased the results by 0.25 points (on a scale 0–10) based on the OLS method, whereas the IV method indicated an impact of 0.51 points. That is, the effect ranged from 0.25 to 0.52 times the standard deviation of grades (0.98).

Table 3. Dual VET effect on grades: marginal effects.

Thus, our results confirm the two hypotheses. On the one hand, Dual VET model increases students’ degree completion compared to school-based VET. On the other hand, Dual VET allows students to get a higher average grade with regards to school-based VET.

However, as mentioned above, grades are not strictly comparable between students since grading patterns differ significantly by area of study and also by training centre. Also, each cohort might have been graded differently because of dissimilarities in misbehaviour or changes in teaching staff composition. For these reasons, we relied more on standardised grades that account for the distribution of grades within a peer group (centre, cohort, and area of study). Our estimated impact is almost one standard deviation. That is, Dual VET students showed a higher grade of 0.93 times the standard deviation compared to their peers after instrumenting by Dual VET availability within 5 km (Column 3).

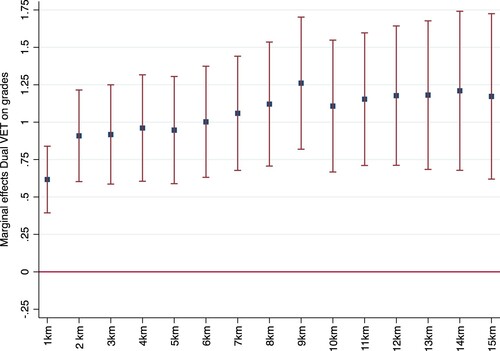

We wanted to analyse how robust these results were based on other distances than the considered 5 km for the selected instrument. It is well known that Spanish (and Catalan) students do not travel much to attend secondary education and even university. However, some students might have faced budgetary restrictions that influenced their choice. For this purpose, depicts the Dual VET impact on instrumented standardised grades after considering distances from 1 to 15 km, with a confidence interval for these effects. There are no significant differences across the various specifications, although there is a slightly positive trend. Additionally, we wondered about the effect produced by the distance between the company where the internship takes place and the school centre. For this purpose, we looked for the geographical coordinates of each work centre where internships took place for all students from each school centre. Then, after computing all distances between schools and workplaces we calculated the average distance of internships by school centre/academic year. Our main results about Dual VET were robust to the consideration of this variable into the list of covariates.

If other educational variables are considered, as shows, online and blended teaching had no effect on grades. In comparison with public schools, attending a private or a vouchered school reduced students’ grades. Finally, those in the higher level of vocational education (HNC) got higher marks than those in the lower level (VET).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we considered the effect of Dual VET on grades and degree completion in Catalonia (Spain). This is a new topic that we are able to analyse since Catalonia is implementing a Dual VET system in the context of traditional VET, so that the systems coexist. The research raised two hypotheses. Compared to school-based VET, we analysed whether Dual VET model increases students’ degree completion as well as allows students to get a higher average grade.

All our regressions show that Dual VET had a positive effect on grades, irrespective of the method and outcome used. In fact, the IV estimation methods depict a greater impact than the OLS results with an estimated impact of almost one standard deviation. Moreover, results show that Dual VET increases the probability of degree completion.

Thus, it seems that the transformation of the Catalan VET into a Dual VET may have positive effects on the system, since the latter increases graduation and grades. Therefore, we recommend expanding the Dual VET system so that the benefits seen in this paper are generalised and the efficiency of the VET system is increased. The positive effect on completion is very relevant since Spain has a high rate of early school leaving (Bayón-Calvo et al., Citation2020). This expansion must consider the Catalan education and productive systems as well as import the elements that have made this training system a success story in countries like Germany.

It has to be considered that the positive effects of Dual VET on students’ academic path may also mean better career paths for graduates, at least in their school to work transition. Therefore, the transition of the Catalan (and Spanish) VET systems seems desirable, although there should be an awareness of the existing problems of social stratification and undesirable long-term labour market effects that should be analysed. In addition, some of the characteristics of the Dual VET system should be analysed, such as the use of contracts or scholarships, for example, to find out which elements provide the greatest benefit to students, companies and the education system.

The analysis presents some limitations. Thus, although some students’ personal characteristics are taken into consideration, there is no information on family characteristics. This has to be kept in mind considering the effect of family socioeconomic characteristics as well as parents’ involvement with the educational process on students’ results (Goldstone et al., Citation2021; Hanushek & Luque, Citation2003; Mora & Escardíbul, Citation2018).

This study opens some future lines of research. Thus, further research should focus on the following four lines of analysis. Firstly, an extended longitudinal analysis would provide long-term information on the effects of taking Dual VET, both in the educational system as well as in the labour market. Secondly, it would be interesting to analyse the satisfaction of companies, schools and students with the implementation of Dual VET, since it would provide qualitative information on this process. Thirdly, considering differences by areas of study would show if the results exposed in this study differ significantly by area. Finally, a regional analysis would be recommended to observe similarities and differences in the effects of the implementation of Dual FP on academic performance by Autonomous Communities. This study would allow consideration of the effects of Dual VET under the frame of other VET regulations. In the context of the new VET Spanish Law just approved, it could be interesting to study the evolution of Dual VET effects on achievement, having as a variable the changes on the new model.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Department of Education of the Catalan government and IDESCAT for the provision of data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 LOGSE: General Organic Act of the Educational System approved in 1990; LOE: Organic Act of Education of 2006.

References

- Agarwal, L., Brunello, G., & Rocco, L. (2019). The pathway to college (IZA Discussion Paper 12691). Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3475797

- Altreiter, C. (2021). Drawn to work: What makes apprenticeship training an attractive choice for the working-class. Journal of Education and Work, 34(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1858228

- Ashton, D., & Green, F. (1996). Education, training and the global economy. Cambridge University Press.

- Bayón-Calvo, S., Corrales-Herrero, H., & De Witte, K. (2020). Assessing regional performance against early school leaving in Spain. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101515

- Bentolila, S., & Jansen, M. (2019). La implantación de la FP dual en España: La experiencia de Madrid. Studies on the Spanish Economy, Article eee2019-32. FEDEA.

- Bishop, J. H., & Mane, F. (2004). The impacts of career-technical education on high school labor market success. Economics of Education Review, 23(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.04.001

- Bol, T., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2013). Educational systems and the trade-off between labor market allocation and equality of educational opportunity. Comparative Education Review, 57(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1086/669122

- Boyer, R., & Caroli, E. (1993, November). Production regimes, education and training systems: From complementary to mismatch? [Paper presentation]. RAND Conference on Human Capital and Economic Performance (Vol. 17). Santa Bárbara, CA, USA.

- Brunello, G., & Rocco, L. (2017). The labor market effects of academic and vocational education over the life cycle: Evidence based on a British cohort. Journal of Human Capital, 11(1), 106–166. https://doi.org/10.1086/690234

- Brunetti, I., & Corsini, L. (2019). School-to-work transition and vocational education: A comparison across Europe. International Journal of Manpower, 40(8), 1411–1437. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-02-2018-0061

- Campolieti, M., Fang, T., & Gunderson, M. (2010). Labour market outcomes and skill acquisition of high-school dropouts. Journal of Labor Research, 31(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-009-9074-5

- Cedefop (2019). 2018 European skills index (Cedefop reference series; No 111). Publications Office of the European Union. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/564143

- Coleman, J. S., Campbell, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. L. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. US Government Printing Office.

- CTESC. (2017). La formació professional en el sistema educatiu català (CTESC. Col·lecció Estudis i Informes. 46). CTESC (The Labour, Economic and Social Council of Catalonia).

- DE. (2021). L’FP Dual en xifres. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://agora.xtec.cat/fpdual/dual-en-imatges/lfp-dual-en-xifres/

- Dronkers, J., & Robert, P. (2008). Differences in scholastic achievement of public, private government-dependent, and private independent schools a cross-national analysis. Educational Policy, 22(4), 541–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904807307065

- Euler, D. (2013). Germany's dual vocational training system: A model for other countries? Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Eurydice. (2022). Spain. Organisation of the education system and of its structure. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/organisation-education-system-and-its-structure-79_en

- Fürstenau, B., Pilz, M., & Gonon, P. (2014). The dual system of vocational education and training in Germany. What can be learnt about education for (other) professions. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (pp. 427–460). Springer.

- Gangl, M. (2003). Returns to education in context: Individual education and transition outcomes in European labour markets. In W. Müller & M. Gangl (Eds.), Transitions from education to work in Europe – the integration of youth into EU labour markets (pp. 156–185). Oxford University Press.

- Gencat. (2020). Departament d'Educació. Cursos anteriors. Retrieved May 18, 2021, from https://web.gencat.cat/

- Gencat. (2021). Departament d’Educació. FP dual. Retrieved May 18, 2021, from https://agora.xtec.cat/fpdual/informacio/que-es-la-formacio-professional-dual/

- Gencat. (2022). Departament d’Educació. Empreses-FP dual. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://educacio.gencat.cat/ca/arees-actuacio/empreses-fpdual/

- Gessler, M. (2017). Educational transfer as transformation: A case study about the emergence and implementation of dual apprenticeship structures in a German automotive transplant in the United States. Vocations and Learning, 10(1), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9161-8

- Goldstone, R., Baker, W., & Barg, K. (2021). A comparative perspective on social class inequalities in parental involvement in education: Structural dynamics, institutional design, and cultural factors. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1974347

- Grollmann, P., Steedman, H., Jansen, A., & Gray, R. (2017). Building apprentices’ skills in the workplace: Car service in Germany, the UK and Spain (CVER Research Discussion Paper, 11).

- Häkkinen, I. (2006). Working while enrolled in a university: Does it pay? Labour Economics, 13(2), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2004.10.003

- Hanushek, E. A., & Luque, J. A. (2003). Efficiency and equity in schools around the world. Economics of Education Review, 22(5), 481–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(03)00038-4

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2010). The economics of international differences in educational achievement (NBER Working Paper Series N. 15949). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hanushek, E. A., Woessmann, L., & Zhang, L. (2011). General education, vocational education, and labor-market outcomes over the life-cycle (Technical Report Discussion Paper No. 6083). IZA Institute for the Study of Labor.

- Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2011). The economics of international differences in educational achievement. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 3, 89–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00002-8

- Hippach-Schneider, U., Weigel, T., Brown, A., & Gonon, P. (2012). Are graduates preferred to those completing initial vocational education and training? Case studies on company recruitment strategies in Germany, England and Switzerland. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 65(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2012.727856

- Hyland, T. (2002). On the upgrading of vocational studies: Analysing prejudice and subordination in English education. Educational Review, 54(3), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191022000016338

- Jansen, A., & Pfeifer, H. (2017). Pre-training competencies and the productivity of apprentices. Evidence-Based HRM, 5(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-05-2015-0018

- Jansen, A., & Pineda-Herrero, P. (2019). Dual apprenticeship in Spain–Catalonia: The firms’ perspective. Vocations and Learning, 12(1), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-09217-6

- Juul, I., & Jørgensen, C. H. (2011). Challenges for the dual system and occupational self-governance in Denmark. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 63(3), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2011.560393

- Latina, J. (2017). Should I stay or should I switch? An analysis of transitions between modes of vocational education and training. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 69(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2017.1303784

- Low, H., Meghir, C., & Pistaferri, L. (2010). Wage risk and employment risk over the life cycle. American Economic Review, 100(4), 1432–1467. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.4.1432

- Meer, J. (2007). Evidence on the returns to secondary vocational education. Economics of Education Review, 26(5), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.04.002

- MEFP. (2022). Sistema educativo Español. Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Retrieved March 11, 2022. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/contenidos/in/sistema-educativo.html.

- Mora, T. (2021). Informe formació professional a Catalunya (dades administratives: cursos acadèmics 2015–2019). ACV Edicions.

- Mora, T., & Escardíbul, J. O. (2018). Home environment and parental involvement in homework during adolescence in Catalonia (Spain). Youth & Society, 50(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X15626050

- Morrison, K., & No, A. I. O. (2007). Does repeating a year improve performance? The case of teaching English. Educational Studies, 33(3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055690701423333

- Neyt, B., Verhaest, D., & Baert, S. (2020). The impact of dual apprenticeship programmes on early labour market outcomes: A dynamic approach. Economics of Education Review, 78, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102022

- OECD. (2010). Learning for jobs.

- Pineda-Herrero, P., Ciraso-Calí, A., & Arnau-Sabatés, L. (2019). La FP dual desde la perspectiva del profesorado: elementos que condicionan su implementación en los centros. Educación XX1, 22(1), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.21242

- Pineda-Herrero, P., Quesada-Pallarès, C., Espona-Barcons, B., & Mas-Torelló, O. (2015). How to measure the efficacy of VET workplace learning: The FET-WL model. Education + Training, 57(6), 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2013-0141

- Polidano, C., & Tabasso, D. (2014). Making it real: The benefits of workplace learning in upper-secondary vocational education and training courses. Economics of Education Review, 42, 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.06.003

- Protsch, P., & Solga, H. (2016). The social stratification of the German VET system. Journal of Education and Work, 29(6), 637–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1024643

- Quintini, G., Martin, J. P., & Martin, S. (2007). The changing nature of the school-to-work transition process in OECD Countries (IZA Discussion paper, 2582).

- Robertson, E. (2011). The effects of quarter of birth on academic outcomes at the elementary school level. Economics of Education Review, 30(2), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.10.005

- Rowe, A. D., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2017). Developing graduate employability skills and attributes: Curriculum enhancement through work-integrated learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 18(2), 87–99. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/11267

- Ryan, P. (2001). The school-to-work transition: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(1), 34–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.39.1.34

- Scandurra, R., & Calero, J. (2020). How adult skills are configured? International Journal of Educational Research, 99, Article 101441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.06.004

- Scholten, M., & Tieben, N. (2017). Vocational qualification as safety-net? Education-to-work transitions of higher education dropouts in Germany. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-017-0050-7

- Shaw, A. J. (2012). The value of work experience in outcomes for students: An investigation into the importance of work experience in the lives of female undergraduates and postgraduate job seekers. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 64(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2011.628756

- Steedman, H. (2005). Apprenticeship in Europe: “Fading” or flourishing? CEPDP (710). Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Valiente, O., & Scandurra, R. (2017). Challenges to the implementation of dual apprenticeships in OECD countries: A literature review. In M. Pilz (Ed.), Vocational education and training in times of economic crisis (pp. 41–57). Springer.

- Van der Velden, R., Welter, R., & Wolbers, M. (2001). The integration of young people into the labour market within the European Union: The role of institutional settings (Working Paper, 2001/7E). Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market.

- Weisshaar, K., & Cabello-Hutt, T. (2020). Labor force participation over the life course: The long-term effects of employment trajectories on wages and the gendered payoff to employment. Demography, 57(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00845-8

- What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth. (2015). Evidence review 8: Apprenticeships.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive characteristics for overall, dual VET, and traditional VET students.

Table A2. Overall determinants of grades: marginal effects (IV estimation).