Abstract

Efficient knowledge and information transfer within as well as across organizational boundaries are of a proven importance for survival and growth of firms. At the same time, however, on the one hand, knowledge available within organizations is not always used to its full capacity, at times at the considerable detriment of organizations involved. Furthermore, on the other hand, despite the recognized importance of an efficient interorganizational knowledge transfer, many collaborations have not delivered on their promises. Merges and acquisitions deals, for instance, are prone to fail. The goal of this article is to propose and illustrate a conceptual argument why knowledge and information transfer that crosses departmental and firm boundaries, and in doing so often also domain or disciplinary boundaries, is challenging.

The transfer of knowledge within and between firms has come to be seen as increasingly important for firm performance. If one wants to understand a complex phenomenon of intra- and, what is more, inter-organizational knowledge transfer, one needs to understand first, the different levels of the phenomenon itself (individual, team, project, organizational, interorganizational levels) (cf. Bogers et al. Citation2017); then, different units of analysis (individuals, groups, artifacts, social interactions); diverse needs to be acknowledged; and moreover, various theoretical lenses that tackle knowledge transfer from different angles. To clarify how these different conceptual aspects intervene, we analyze the literature gluing different analytical levels together—please note for reference.

Various Lenses, Inadequate Views

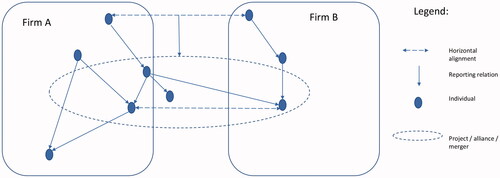

To start with, principal agent theory is developed to understand how rational individuals might interact inside of an organization.Footnote1 In terms of , only vertical reporting relations are assumed in which the principal’s challenge is to make the agent act not in line with their own interests but in line with those of the principal. In addition to the flat assumption of individual preferences and decision-making strategy, this theory in its most basic form does not account for horizontal relations between individuals. In light of this principal agent theory, with reference to , an agent might have different principals. These principals might be from different departments or even from different organizations, as is wont in modern economic circumstances where many different kinds of collaboration are prevalent. In temporary multi-organization projects, alliances, joint ventures, merged organizations, especially when knowledge needs to transfer, an agent might have principals from different organizations. Even when an agent has principals from different departments in the same organizations, as in an organization that has adopted a matrix structure, the agent deals with multiple principals. Principal principal agent theory has recently started to acknowledge as much (Grosman, Aguilera, and Wright Citation2019), but is not offering particular insights as to how to understand the dynamics involved. The principal principal agent dynamics are altered when multiple principals are from different organizations. When a single principal seeks to influence the behavior of multiple agents who are from different parts of a firm or even from different firms, their effectiveness is also impacted (perhaps referred to as a principal agent agent situation).

Social network analysis, which draws on graph theory and is quite heavily used in sociology, looks at knowledge transfer between individuals presented as nodes in a network (Casper Citation2013). Any social entity can be analyzed,Footnote2 with potentially a number of different social networks to be recognized in each organization. Hierarchy in the organization, membership of organization (department), as well as a range of personal characteristics can be included in the (visualized) descriptive, or included in statistical analysis that would also include data for variables that make sense from a social network point of view. Patterns of knowledge transfer, the focus here, are only impacted by the structure of the knowledge transfer network; individuals can only be expected to have a more favorable outcome from the process or impact on the process from their position in the network (Aalbers and Dolfsma Citation2015). While the singular focus on vertical or hierarchical relations is not there in social network analysis, and dynamics in collaboration between different organizations can be analyzed (cf. Dolfsma, Wang, and Van der Bij Citation2019), the nature of the relations between individuals is largely ignored.

Two principals coming from different organizations, or two project team members (agents) who are from different organizations, might well bring organization-specific expectations, routines, and views of the world. One might refer to this as an organization’s culture. The latter potentially creates a testing ground for the principal agent-agent view, as rational consideration is understood as contextual rather than universal, as well as for the social network view of organizations, since interactions depend on (much) more than structure of the network and position in it. Organizational cultures (Dolfsma, Geurts, and Chong Citation2017) might link with a disciplinary predominance in either an organization or even a department within an organization.

Projects might also involve outsiders, say temporarily, in an interim capacity, bringing their own perspective. Outsiders, with a contract that might be more specific than a labor contract of employees tends to be (cf. Dolfsma Citation1998), might be more amenable for steering from a principal, however. Outsiders might also not have the commitment to the organization and its goals required for contributing creative content.

Creativity Crosses Boundaries

Where firms such as Bell Labs could develop the technology required to dominate their businesses, even when a number of businesses developed using the technologies that they also created but did not use,Footnote3 nowadays even the biggest firms, dominating their domineering industries (e.g., ASML–Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography) cannot do so without intense collaboration both within its boundaries across departments as well as across organization boundaries (cf. Bouty Citation2000; Chesbrough Citation2003; Ferrary Citation2003; Aalbers, Dolfsma, and Leenders Citation2016; Dolfsma and Van der Eijk Citation2017). Remember that collaboration can also take the form of acquiring a firm to bring it into a portfolio before it starts to become a competitor as is wont in busines-to-consumer contexts.

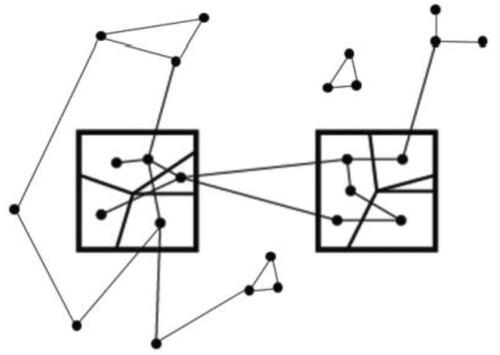

The kind of creativity that is required therefore necessarily involves crossing boundaries —see . Such boundary crossing collaboration exacerbates the conceptual challenges seeking to understand patterns of collaboration. The more parties are involved, the more complicated the organizational and governance issues (see Hofstede Citation1990; Geurts et al. Citation2022). Commitment and loyalty to the organization, or perhaps alternatively referred to as the positive effects of organizational culture, are less likely to stimulate such collaboration when organizational boundaries are crossed. The literature on organizational culture has not (extensively) studied how boundaries within the organization and in particular between organizations affect the influence of culture on people’s behavior. What is needed is a more elaborate view of how relations between individuals form in general.

Figure 2. Knowledge Transfer Crossing Unit and Firm Boundaries

Social Exchange Theory—How Gifts Establish Relations

What is also known, however, outside of social network analysis, is the role of personality characteristics and (organizational) status characteristics. As for the latter, for instance, line-managers operate in a different manner when involved in knowledge transfer compared with employees without a manager role (Dolfsma and Van der Eijk Citation2021). This difference between individuals cannot fully be analyzed from a social network analysis point of view. What is required is a perspective that acknowledges that both the nature of the (evolving) relationship, as well as the qualities that the involved individuals have makes a difference. Qualities of individuals are, of course, ascribed to them by the environment they are imbued in.

Social exchange literature points out that gift exchange plays a vital role in constructing social relations (Boulding Citation1981; Cheal Citation1988; Gouldner Citation1960; Larsen and Watson Citation2001). Gifts may be used to initiate, maintain, or sever relationships with individuals or groups (Cheal Citation1988; Darr Citation2003; Gouldner Citation1960; Larsen and Watson Citation2001; Mauss Citation[1954] 2000). Frequent gift or favor exchange leads to positive emotions and uncertainty reduction which, in turn, generates cohesion and commitment to exchange relations (Lawler, Yoon, and Thye Citation2000). Gifts may be exchanged for both instrumental and more purely altruistic reasons (Blau Citation1964; Ekeh Citation1974; Homans Citation1974; Mauss [1954] 2000). Even though self-interest and instrumental considerations may play a role, for gifts—rather than prices or bribes (cf. Rose-Ackerman Citation1998)—nature, value, and moment of the counter-gift are purposefully not specified. Community-specific rituals signal “expectation of the persistence and fulfilment of the […] social order” (Barber Citation1983; cf. Gambetta Citation1988). Creation of trust is implicit as there is the expectation of a counter-gift in gift exchange between individuals (cf. Bourdieu Citation1992; Darr Citation2003). It is this expectation of reciprocity and perceived sense of equity over the longer term that makes the exchange mutually beneficial, and therefore its continuance is to be expected (Cook and Emerson Citation1984).

Enforcement is self-regulating, since, between equals, if one partner fails to reciprocate, the other actor is likely to discontinue the exchange (Nye Citation1979). Because gift exchange is unbalanced when viewed at any one particular point in time, a longitudinal perspective more accurately reveals the nature of gift giving. A deferred return obligates one individual to another and creates “social debt.”Footnote4 Gift exchange is characterized by three principles (Mauss [1954] 2000). To be part of an (informal) community, people are obliged to (1) give, (2) receive, and (3) reciprocate (cf. Dore Citation1983; Gouldner Citation1960; Simmel Citation1996). These obligations are social, in that they are “enforced” by the community. In addition, they may have moral overtones. Acceptance of the gift is, to a certain extent, acceptance of the giver and the relationship between the individuals (Larsen and Watson Citation2001). A gift perceived as improper by the receiver may be rejected, may fail to initiate a relation, and may harm an existing relation and the trust inculcated there. Refusal of the initial gift marks the refusal to initiate the dynamic of exchange; thus to refuse a gift is to refuse a relationship and one’s role in that relation (Ferrary Citation2003; Mauss [1954] 2000).

Reciprocity is open to discretion as to the value and form of the counter-gift: the currency with which the obligation is repaid can be different from the form with which they were incurred. Making an equal-return “payment” in gift exchange, however, is tantamount to discontinuing the relationship. Gift exchange is diachronous since reciprocity is open to discretion with regard to time; a gift is not reciprocated by immediate compensation, but instead by a deferred form of compensation (Bourdieu Citation1977 and 1992; Ferrary Citation2003; Mauss [1954] 2000). Material value of gifts exchanged can be compensated for by obvious inculcation of immaterial value—such as time, effort, and creativity—in the counter-gift.

The instrumental reason for giving in the first place is to be able to establish a relation that will be beneficial in the long run, possibly by being able to tap into the other relations that the receiving party maintains (Ferrary Citation2003). The exact nature or moment of the counter-gift is thus not specified beforehand. In addition to being “silent,” gifts or favors are versatile in the sense that form and content can vary extensively, depending on the circumstances and broader context. Although the type of gifts and favors as well as the rituals involved, due to legal and/or normative constraints, can transform over time, the practice of informal personalized exchange has been demonstrated in many organizational settings (Allen Citation1977; Von Hippel Citation1987).

Concluding Comments

In modern organizations work connections between people often cross either internal or between-organizations boundaries. In modern organizations, work-connections often are more like informal relations than before. Mainstay economic and organization theory such as principal agent theory or social network analysis cannot readily explain the dynamics involved in such relations. In this short article we have presented social (gift) exchange theory as a lens that helps understand the relations in modern organizations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wilfred Dolfsma

Wilfred Dolfsma, Maral Mahdad, and Valentina Materia are in the Business Management and Organization group at Wageningen University. Ekaterina Albats is at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education.

Maral Mahdad

Wilfred Dolfsma, Maral Mahdad, and Valentina Materia are in the Business Management and Organization group at Wageningen University. Ekaterina Albats is at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education.

Ekaterina Albats

Wilfred Dolfsma, Maral Mahdad, and Valentina Materia are in the Business Management and Organization group at Wageningen University. Ekaterina Albats is at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education.

Notes

1 Principal agent theory is used too, and perhaps foremost, to understand managers of an organization’s relationship to owners of that organization. Here, for the sake of simplicity, we restrict ourselves to relations between individuals inside an organization and individuals of only two organizations collaborating to work towards a shared goal.

2 Indeed, a network consisting of nodes—and relations (ties) between them—need not be individuals. Nodes can also be departments, organizations, regions, nations, and also computers or patent classes, for instance (Aalbers and Dolfsma Citation2015).

3 See Gertner (Citation2012). Technologies developed here were sometimes unnoticed, and at times forcefully extracted from it for use by others (Watzinger et al. Citation2020).

4 If the obligations could in fact be enforced and imposed on by third parties, we would be talking about market transactions.

References

- Aalbers, Rick, and Wilfred Dolfsma. 2015. Innovation Networks. London and New York: Routledge.

- Aalbers, Rick, Wilfred Dolfsma, and Roger Leenders. 2016. “Vertical and Horizontal Cross-Ties: Benefits of Cross-Hierarchy and Cross-Unit Ties for Innovative Project Teams.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 33 (2): 141–153.

- Allen, Thomas J. 1977. “Managing the Flow of Technology.” Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Barber, Bernard. 1983. “The Logic and Limits of Trust.” New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Blau, Peter. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- Bogers, Marcel, Ann K. Zobel, Allan Afuah, Esteve Almirall, Sabine Brunswicker, Linus Dahlander, Lars Frederiksen, et al. 2017. “The Open Innovation Research Landscape: Established Perspectives and Emerging Themes Across Different Levels of Analysis.” Industry & Innovation 24 (1): 8–40.

- Boulding, Kenneth E. 1981. A Preface to Grants Economics—The Economics of Love and Fear. New York: Praeger.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory in Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1992. The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bouty, Isabelle. 2000. “Interpersonal and Interaction Influences on Informal Resource Exchanges Between R&D Researchers Across Organizational Boundaries.” Academy of Management Journal 43 (1): 50–65.

- Casper, Steven. 2013. “The Spill-Over Theory Reversed: The Impact of Regional Economies on the Commercialization of University Science.” Research Policy 42 (8): 1313–1324.

- Cheal, David. 1988. The Gift Economy. London and New York, Routledge.

- Chesbrough, Henry W. 2003. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Cook, Karen, and Richard Emerson. 1984. “Exchange Networks and the Analysis of Complex Organizations.” In Research on the Sociology of Organizations, edited by S. Bacharach and E. Lawler. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Darr, Asaf. 2003. “Gifting Practices and Inter-Organizational Relations: Constructing Obligations Networks in the Electronics Sector.” Sociological Forum 18 (1): 31–51.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred. 1998. “Labor Relations in Changing Capitalist Economies—The Meaning of Gifts in Social Relations.” Journal of Economic Issues 32 (2): 631–638.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, Amber Geurts, and Lisa Chong. 2017. “Reproducing the Firm: Routines, Networks, and Identities.” Journal of Economic Issues 51 (2): 297–304.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, and Rene Van der Eijk. 2017. “Network Position and Firm Performance—The Mediating Role of Innovation.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 29 (6): 556–568.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, and Rene Van der Eijk. 2021. “Lab Scientists’ Innovativeness—A Case Study of Networks and Favor Exchange.” In The Gift in the Economy and Society. Edited by S. Kesting, I. Negru, and P. Silvestri, 79–97. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dolfsma, Wilfred, Xiao Wang, and Hans J.D. Van der Bij. 2019. “Individual Performance in a Cooperative R&D Alliance: Motivation, Opportunity and Ability.” R&D Management 49 (5): 762–774.

- Dore, Ronald. 1983. “Goodwill and the Spirit of Market Capitalism.” British Journal of Sociology 34 (4): 459–482.

- Ekeh, Peter P. 1974. Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ferrary, Michel. 2003. “The Gift Exchange in the Social Networks of Silicon Valley.” California Management Review 45 (4): 120–138.

- Gambetta, Diego. (ed.) 1988. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gertner, Jon. 2012. The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation. London and New York: Penguin.

- Geurts, Amber, Wilfred Dolfsma, Thijs Broekhuizen, and Katherina Cepa. 2022 “Tensions in Multilateral Coopetition: Findings from the Disrupted Music Industry.” Working paper Wageningen University.

- Gouldner, Alvin W. 1960. “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.” American Sociological Review 25 (2): 161–178.

- Grosman, Anna, Ruth V. Aguilera, and Michael Wright. 2019. “Lost in Translation? Corporate Governance, Independent Boards and Blockholder Appropriation.” Journal of World Business 54 (4): 258–272.

- Hofstede, Geert. 1990. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: Harper Collins Business.

- Homans, George C. 1974. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Larsen, Derek, and John J. Watson. 2001. “A Guide Map to the Terrain of Gift Value.” Psychology and Marketing 18 (8): 889–906.

- Lawler, Edward J., Jeongkoo Yoon, and Shane R. Thye: 2000. “Emotion and Group Cohesion in Productive Exchange.” American Journal of Sociology 106 (3): 616–657.

- Leenders, Roger, and Wilfred Dolfsma. 2016. “Social Networks for Innovation and New Product Development.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 123 (2): 33–131.

- Mauss, Marcel. (1954) 2000. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. New York: Norton.

- Nye, F. I. 1979. “Choice, Exchange and the Family.” In Contemporary Theories About the Family. Edited by E. R. Burr et al. New York: Free Press.

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1998. “Bribes and Gifts.” In Economics, Values and Organization. Edited by A. Benner and L. Putterman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Simmel, Georg. 1996. “Faithfulness and Gratitude.” In The Gift: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Edited by A. E. Komter. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Von Hippel, Eric 1987. “Cooperation Between Rivals: Informal Know-How Trading.” Research Policy 16 (6): 291–302.

- Watzinger, Martin, Thomas A. Fackler, Markus Nagler, and Monika Schnitzer. 2020. “How Antitrust Enforcement Can Spur Innovation: Bell Labs and the 1956 Consent Decree.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12 (4): 328–359.