ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ perspectives on promoting reading and writing for pupils with various linguistic backgrounds in grade 1. Focus group interviews were conducted with 17 teachers who work in preschool classes and in grade 1. The teachers’ perspectives on reading and writing can be characterised as balanced, in the sense that the teachers describe how they work with both the technical and the learning-oriented dimension. The number of different languages spoken in their classes is regarded in a positive manner, but it also leads to major challenges, such as not having enough time for all of the pupils and not having sufficient knowledge of multilingualism.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ perspectives on how to promote reading and writing for pupils with various linguistic backgrounds in grade 1 of primary school. The teachers included in the study, like most teachers in Swedish schools, have an increasingly heterogeneous composition of pupils in their classrooms. How children’s different abilities, experiences and needs are dealt with at school contributes to a large degree to the development of the children’s written language. The increased diversity in Swedish classrooms can be linked to a variety of factors on different social and political levels. One of them is a movement towards more inclusive schools for all children, based on the perspective of inclusiveness stated in international agreements such as the Salamanca Convention (UNESCO, Citation2006). Another factor, especially addressed in this study, is that an increasing number of pupils do not have Swedish as their first or only language. This can be illustrated by the fact that around 27% of pupils in compulsory schooling are entitled to mother tongue tuition, according to statistics from the Swedish National Agency for Education (Citation2017). The teachers in this study are working in schools where many different languages are spoken among the pupils. The curriculum for compulsory school, preschool classes and leisure-time centres, Lgr11 (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2016) contains syllabuses and skills requirements both in Swedish and in Swedish as a second language. The skills requirements in Swedish and Swedish as a second language for grade 1 have the same wording:

the pupil can read sentences in simple, familiar texts that are relevant to the pupil by using sounding strategy and reading whole words to some extent. By commenting and retelling a part of the content that is important to the pupil in a simple way, the pupil demonstrates the beginnings of reading comprehension. (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016, p. 252 and p. 264)

What approaches to teaching reading and writing among pupils with various linguistic backgrounds can be identified in the interviews with teachers?

How do the teachers in the study describe their didactic work on encouraging all pupils to learn to read and write Swedish or learn Swedish as a second language?

Theorising Reading and Writing

The path to mastering the written language is not the same for all children. Some children learn to read and write in a relatively unnoticed way by taking part in various reading and writing practice sessions, while for other children the path is a winding one, with many pauses and obstacles. The following section describes some areas that according to research have considerable significance for the development of written language.

According to Vygotsky (Citation1934/Citation1986), there are major differences between the spoken language and the written language with regard to both structure and function. Spoken and written language are tightly interwoven, but written language is a constructed symbol language to depict speech. When using written language, there are no significant props such as sound, gestures, mime, prosody or moreover a recipient who is immediately present, “the development of writing does not repeat the development of oral speech” (p. 181). A recurring method of defining reading is through what is called “The Simple View of Reading” (Gough & Tunmer, Citation1986), that is that reading is regarded as the product of two interacting processes, decoding and language comprehension (DxL = R). Decoding refers to the process that converts the alphabetic code, graphemes, to phonemes. It is regarded as a condition for the development of reading to higher levels that this decoding becomes automatic and it is a critical factor in relation to problems in reading and writing. If decoding is perceived as hard work, then both interest in the text and understanding of the text will suffer. According to Ehri (Citation2005) four faces can be identified in the development of decoding: pre-alphabetic, partial alphabetic, full alphabetic, and consolidated alphabetic. Simplified this means identifying words with help from visual clues in the first face, understanding and learning how the graphemes correspond to the phonemes in the second and third, and then in the fourth face using the technique automatically. Language comprehension in the model described above is linked to how one processes and interprets the message contained in the text being read and consequently is a complex process that involves understanding and thinking on different levels (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014). As concluded by Lipka and Siegel (Citation2012), a variety of cognitive processes (working memory and phonological, syntactic, and morphological awareness) are important for reading comprehension, and the skills underlying reading comprehension are similar for monolingual and multilingual pupils. Learning to read and write requires that one has oral mastery of the language that one is going to read and write (Chang & Sylva, Citation2015; Hyltenstam, Citation2010). A key factor here, particularly with regard to language comprehension, is vocabulary. Expanding and semantically organising their vocabulary is of vital importance for children who are developing their second language.

There are some factors that research points to as particularly important in the acquisition of reading and writing. One of these concerns language awareness that is, being able to notice the difference between the content and the forms of language (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014). Language awareness entails a metacognitive dimension and there are numerous indications that multilingual children develop this ability better than monolingual children because of their access to different languages (Chang & Sylva, Citation2015; Salameh, Citation2012; Snow et al., Citation2005). With regard to pupils that risk experiencing difficulties in reading and writing in particular, the phonological awareness is considered vitally important, as it concerns understanding that in the spoken language sounds, phonemes, are represented by letters, graphemes, and being able to apply this principle (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014; Taube et al., Citation2015). To summarise, both the decoding (D) and the language comprehension (L) dimensions are of great importance in developing skilled reading and writing.

One model often referred to when emphasising that reading and writing are both an individual skill and at the same time a social activity, is the one developed by Luke and Freebody (Citation1999). This model describes four different resources that must be developed to become an efficient reader: 1) The reader as code breaker, 2) The reader as text participant, 3) The reader as text user, and 4) The reader as text analyst. The model can be used to draw attention to the balanced and integrated learning environments that many researchers agree are necessary to encourage different children’s reading and writing (Hedman, Citation2009; Hyltenstam, Citation2010; Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014; Snow & Juel, Citation2005).

Teaching Reading and Writing

Research into children’s development in reading and writing has in various ways pointed to the importance of stimulating learning environments and teaching in preschools and schools (Alatalo, Citation2011; Damber, Citation2010; Fast, Citation2007; Norling, Citation2015). What is then regarded as successful in the teacher’s work on promoting reading and writing for all pupils during the first year of formal schooling? According to Vygotsky (Citation1934/Citation86), learning develops in a mutual interaction between individuals’ biological circumstances and external influences, such as teaching. The research carried out in recent decades has crystallised into some didactic areas that are pointed out as particularly important in promoting development in reading and writing (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014; Snow et al., Citation2005; Snow & Juel, Citation2005).

One concept that is important in teaching is what Vygotsky (Citation1934/Citation1986) calls the “zone of the proximal development” (p. 188). The zone of proximal development (ZPD) is linked to maturity in that it requires a certain degree of maturity for the teaching to be possible, but social and cultural factors play an important role in, for instance, language development processes. To summarise and simplify, this means that each child, in addition to an independent competence within one field also has a potential for development and learning, a field in the making that may require pedagogical support from individuals with more competence. The development area looks different for each child, even if they are at the same level with regard to independent competence. In order to create a learning environment based on ZPD, knowledge of where the students are in their learning process, but also what kind of and how much didactical support they benefit from in their learning is required (Hagtvet, Frost, & Refsahl, Citation2016).

A key area that has been emphasised is the value of meeting and processing texts in different ways. As pointed out by Damber (Citation2016), monolingual and especially multilingual children are dependent on meeting written language at an early stage to be able to build up their vocabulary and become familiar with grammatical constructions of the written language. There are also studies showing that teaching that encourages literature and creative activities around the texts has positive consequences, especially for multilingual children (e.g., Cummins, Citation2012). In the didactic work on creating the conditions for children to become readers, the meeting with literature and being able to experience and process the genre is very important (Damber, Citation2010; Hedman, Citation2012).

As mentioned earlier, phonological awareness is one of the basic conditions for being able to grasp written language (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014; Snow & Juel, Citation2005). By offering children structured language games before and early on during the first formal reading and writing lessons, one draws attention to and trains awareness of the forms of the language, something that has been proved to prevent reading and writing difficulties (Lundberg, Frost, & Petersen, Citation1988). Hedman (Citation2012) emphasises the necessity of a child who is going to learn to read and write in a second language being made aware of the linguistic aspects of the respective languages, for instance, the different languages’ orthography, that is the agreement between the sounds and the way they are written down.

With regard to formal teaching of reading and writing, research shows that it is important to have a balance between activities that aim to develop both the technical and creation of meaning sides of reading and writing (Snow & Juel, Citation2005; Taube et al., Citation2015). For children in the risk zone for obstacles of a dyslexia nature, structured teaching about the link between phonemes and graphemes is very necessary. On the other hand, there are other groups of pupils who are more dependent on the teaching focusing not only on technical skills. Cummins (Citation2012) argues that multilingual pupils are dependent on the teaching encouraging and helping the pupils to become interested in using their different languages in the reading and writing activities offered.

Except for the importance of addressing both the technical and the meaning-making dimensions of reading and writing, the choice of teaching method does not appear to be of great significance (Snow & Juel, Citation2005; Taube et al., Citation2015). In some of the few studies reporting the teachers’ perspective on their work with reading and writing in grade 1, the teachers appear to represent a clearly integrated stance. They describe work aimed at developing the pupils’ reading and writing both in terms of individual technical skills and as a social and meaningful activity (e.g., Alatalo, Citation2011; Sandberg, Hellblom-Thibblin, & Garpelin, Citation2015). Teachers in classrooms characterised by linguistic diversity need to embrace the differences and make use of the strengths of pupils developing several languages at the same time (Ortiz & Fránquiz, Citation2016).

A further factor that is important for teaching pupils to read and write is the teacher’s understanding and theoretical knowledge. Earlier research shows that qualified knowledge of the development of reading and writing is required and also of how obstacles can arise and be prevented to ensure that all pupils receive adequate support. In addition to in-depth theoretical competence, there are other dimensions of the teachers’ professionalism that are important in the didactic context, for instance, empathy and respect for the individual child, a deliberative approach and a procedure that extends beyond a method or learning system (Alatalo, Citation2011; Dixon & Wu, Citation2014; Tjernberg & Heimdahl Mattsson, Citation2014).

Teachers in classrooms characterised by linguistic diversity need to embrace the differences, and make use of the strengths of pupils developing several languages at the same time (Damber, Citation2016; Ortiz & Fránquiz, Citation2016; Salameh, Citation2012). The quotation below summarises some important factors for promoting the development of reading and writing a second (or third) language. The authors represent a broadly composed committee of experts, appointed by the United States’ National Research Council, which at the end of the 1990s produced a report on what is beneficial for instruction in reading for multilingual pupils. The report is based on conditions in the United States, but similar conclusions have been reached in Swedish studies.

When the school culture values the linguistic and culture backgrounds of English-language learners, encourages the enhancement of native- language skills and communicates high expectations for academic achievement in English, this augurs well for students (Snow et al., Citation2005, p. 147)

Something that has been discussed in connection with multilingualism is that it can be difficult to discern whether obstacles in learning to read and write are linked to acquiring a new language or whether they concern specific difficulties in decoding or understanding text. As shown in a study by Hedman (Citation2009), it is common both to over- and under-diagnose dyslexia, for instance, among pupils who are multilingual. Multilingualism is not in itself a risk factor for developing reading and writing difficulties. On the contrary, research shows that multilingualism in many cases benefits language awareness, which is so important for learning to read and write (Hagtvet et al., Citation2016; Lipka & Siegel, Citation2012). On the other hand, the increasing requirements for more in-depth reading comprehension in recent years at school means that these pupils are experiencing problems. For a child that has grown up in a different culture from the Swedish one and with another mother tongue, the school language may appear alien and become an obstacle to learning and development (Damber, Citation2010; Salameh, Citation2012).

Method

This small scale study is part of a research project about teachers’ perspective on promoting literacy for pupils with various linguistic backgrounds in preschool, preschool-class and primary school. This article focuses on how primary school teachers talk about and describe their work with promoting reading and writing in first grade class-rooms where an increasing amount of pupils do not have Swedish as their first language. Data were collected using focus group interviews (Wibeck, Citation2000). It seemed appropriate when the aim was to examine the teachers’ didactical beliefs and their descriptions of their practical work. Through the group dynamic and the interaction in this kind of interviews underlying approaches and ideas can be revealed.

Participants

The participants in the focus group interviews were 17 teachers of preschool classes and primary school teachers for grade 1–3. They represent three schools in different socioeconomic and geographical areas in a Swedish municipality. Two of the schools are located in multicultural areas where the pupils speak many different languages. In one of the schools 14 different languages are represented among the pupils, and in the other about 10. A large percentage of the pupils in the third school have Swedish as their first or only language, but there are also pupils with four other mother tongues. The choice of three different schools was partly strategic to reflect differences, but also a kind of convenience sample, because these schools were willing to participate in the project with a group of teachers.

The results presented in this article is primarily based on what is expressed by the primary school teachers regarding teaching reading and writing in grade 1. Primary school teachers usually teach in grade 1 to 3, which means they follow the pupils for three years. Participating primary school teachers in this study were working in grade 1 when the interviews took place. Due to few participants in the project working as teachers in preschool class they were included in groups with the primary school teachers.

The teachers were asked to take part in the larger research project. They were contacted by telephone or personal contact and were informed of the aim of the study and about the ethical guidelines for the research (www.codex.vr.se), which have been carefully observed in the study. This means, among other things, that individuals, schools or municipalities will not be possible to identify when the result is reported.

Data Collection

The three focus groups each included 4–8 participants and were composed of teachers in preschool classes (n = 5) and grades 1–3 (n = 12). The interviews were structured by a manual providing two overarching themes: how language-, reading- and writing-development are defined and understood by the teachers, and teachers’ perspectives on how instructions and learning environments can create conditions for language skills development for pupils with Swedish as a first language as well as for pupils with another language as their mother tongue. The themes included several questions concerning didactical considerations and examples of the practical teaching.

Each interview lasted around 90 min and a moderator, that is, one of the authors, led the discussion. The role of the moderator was to facilitate the discussion and to ensure that all of the fields in the manual were covered. Another task for the moderator, emphasised by Chioncel, Van Der Veen, Wildemeersch, and Jarvis (Citation2003) was to include all of the participants in the conversation. During the interviews, another one of the researchers participated passively as an audience member and took notes.

Data Analysis

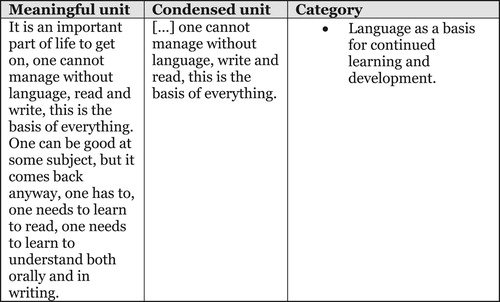

The interviews were recorded in full on an MP3 player. The recordings were then transferred to files on a computer and then anonymised. After this, a latent content analysis was made (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004), where meaningful units responded to the focus of the research question, were marked and systematically entered into an analysis matrix under the headings meaningful units, condensed units and categories ().

Later, the statements were translated into the written language with great caution and precision to avoid damaging their meaning and content (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). In this phase, the results were presented to the participants about six months after the interviews were conducted. The teachers were given an opportunity to discuss the findings in their focus groups (without a moderator this time) and to comment on them. According to Chioncel et al. (Citation2003), the feedback from the participants is important because this kind of research is about “listen[ing] to people and learning from them” (p. 504). Although opportunities to do so were given, there were no comments on the results, but the participants mentioned that they appreciated both the focus groups and the response.

Based on the categories that appeared from the content analysis, it was possible to further analyse overall themes with the support of theoretical starting points. Finally, the analyses of the focus group interviews were compiled into the text presented under the results.

Results

The results of the study are structured according to the two research questions, that is, what has emerged in the interviews regarding the teachers’ approach to teaching reading and writing in a class-rooms characterised by linguistic diversity and how they describe their didactic work on encouraging all pupils to learn to read and write Swedish and Swedish as second language.

Teachers’ Approach

Something that was mentioned by teachers in grade 1 is the importance of all pupils developing Swedish or Swedish as a second language. This language permeates all subjects and forms the basis for continued learning and success at school, “one cannot manage without language, read and write, this is the basis of everything” is a quotation that represents the views of the participating teachers. According to the teachers, entry to grade 1 of compulsory school entails a large and important step with regard to the development of reading and writing skills: “the step from preschool class to compulsory school is a very big one. Suddenly there are lots of goals to be attained, demands are made”. The teachers refer to the curriculum’s requirements regarding Swedish or Swedish as a second language, which state for instance that pupils shall be able to read at the end of grade 1. The basic condition for attaining this is the Swedish language, according to the teachers.

With regard to multilingual pupils, the teachers say that it is a major challenge that the pupils have such different abilities, experiences and needs. It could be a question of earlier experiences, such as schooling or traumatic events during flight from a previous home country but also linguistic differences, such as the differences between language sounds or writing in different languages. The teachers mainly talk about the instruction they are responsible for during the interviews, that is, instruction in Swedish and Swedish as a second language (SVA). Mother tongue teaching and study guidance in mother tongue are provided for pupils with another first language than Swedish at all schools included in the study.

The statements made in the interviews reveal an uncertainty over how to relate to the pupils using their different languages in the classroom, which is expressed as follows by one of the teachers taking part.

We have encouraged them to talk and I do not know if this is right or wrong. I am bilingual so I have encouraged them to speak in both languages.

Something that is emphasised here is that the multilingual pupils must be given room in oral exercises and discussions and that the didactic value of the lessons creating structure for this. The teachers say that multilingual pupils need more time and opportunity to be heard in discussions.

The multilingual pupils, there must be room for them in discussions, it must be structured so that everyone has a chance to talk and is given time to talk. Yes, there are many aspects to bear in mind. I think it is difficult. The more you talk about it, the more complicated it becomes.

Well, I think, when I listen to you, I mean, that we also have the problem of being sufficient to deal with everything, I have such a guilty conscience. Partly because I do not really have time when I have 23 pupils and this includes the new arrivals, and partly because I have little knowledge of how I can best help build up their language // … //how shall I show the concepts? How shall I build up a vocabulary based on association?

Based on the three focus group interviews, it becomes clear that a common stance among the teachers is that they regard reading and writing as both an individual skill and a social activity, and that this approach clearly emerges in their descriptions of the practical didactic work in the classroom.

Teachers’ Descriptions of the Didactic Work

An important foundation in the early reading and writing instruction is to survey where the pupils lie in their reading and writing processes to be able to adapt the teaching as far as possible to the different pupils. The focus group interviews mention several different qualitative and quantitative ways of surveying and making visible the pupils’ learning and development. One example of a quantitative survey is the screenings, often through standard tests, that are carried out in many schools. As implied in the term screening, it is a question of gaining an overall picture of all pupils, being able to identify at an early stage those who are assessed to be at risk of facing difficulties but also as a basis for continued instruction.

However, this is one way of looking at things, she is a very good reader so you don’t need to put in more effort there, but here we have someone who hasn’t come so far in their development. Then I have some sort of picture of how I should continue with my teaching.

The teachers in grade 1 say that they use several different methods and ways of working when teaching pupils to read and write.

Yes, but I think that one can, one mixes it a bit. One can see that one thing does not rule out another, one can learn in several different ways. One child may learn by sounding out letters and words and putting the sounds together, while another child does not hear this and one has to use syllables instead.

The teachers also emphasise the importance of together studying different types of text, by discussing the text and developing strategies for reading comprehension. In this context, reading aloud plays a special role, particularly for the lower school years, not just to develop reading comprehension, but also to provide reading experiences.

I still read to entertain, I want to have a good book to read to the children, but we also work around the texts and I do not believe the children even realise it, they just listen and answer questions and so on, and I think this kind of measure works well, gives a lot.

Mathematics, well I work on reading there. I read headings and look at the text in the Maths book and we leaf through the chapter, “what looks interesting?” so there are a lot of strategies. You work with reading strategies in the Maths book, the social studies book, the science book, everywhere.

Are there a lot of multilingual pupils? I have to think like this to know how to teach those who do not have so much time in the Swedish as a second language teaching.

The teachers say that the instruction should be pleasurable and emphasise that they try to take into account the multilingual pupils’ interests in the classes and to create a context they can understand. The teachers feel that it is particularly important for this pupil group that the instruction is based on existing skills.

So it is very individual, and there is a large spread when it comes to previous knowledge, but one quite simply has to start at the place they are at. And when you start school this means learning, being able to understand spoken Swedish, being able to express oneself in a day-to-day context. And then building onto this the alphabet and learning to read and write and expanding one’s vocabulary.

I like being able to offer lots of different methods, so we work with digital tools, and I think this is great. For instance, for our multilingual pupils who do not have the sounds, we have a different keyboard, so you can hear the sounds and press the keys and get feedback directly.

In the interviews, the teachers describe factors that lie outside the actual didactic work in the classroom that also has considerable significance for the pupils’ opportunities to learn to read and write. This includes collaboration between class teachers and other professional categories such as special teachers, speech therapists, psychologists and with regard to multilingual pupils, collaboration with teachers of Swedish as a second language and mother tongue teachers.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to deepen the understanding of teachers’ perspectives on promoting reading and writing development for pupils with various linguistic backgrounds in grade 1.

The instruction in reading and writing described by the teachers in the interviews is in Swedish and/or Swedish as a second language. Compared with earlier school forms such as preschools and preschool classes, the entry into compulsory school entails a division into different subjects, such as Swedish, Swedish as a second language and mother tongue teaching. For the teachers in the interviews who teach pupils in grade 1, the instruction is regulated by syllabuses, knowledge requirements and timetables (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2016). Targeted instruction in Swedish/Swedish as a second language is extremely important for pupils with another mother tongue to be able to become multilingual (Hedman, Citation2012; Hyltenstam, Citation2010), but it should be regarded as one component of a larger pattern. In this way, what is revealed in this study is the part of the pattern that concerns Swedish and Swedish as a second language, it does not provide an overall picture of the conditions created for the individual multilingual pupils’ development of language, reading and writing. Therefore, for instance, many pupils in grade 1 take part with a different first language than Swedish in the reading and writing instruction in Swedish, parallel with what they are learning in the classes in Swedish as a second language.

There are major differences between spoken language and written language to the extent that they belong to different communication systems (Hagtvet et al., Citation2016), but at the same time they can be understood as two different sides of the same coin. The development of spoken language forms the basis for developing written language, according to Vygotsky (Citation1934/Citation1986), and activities that stimulate spoken language development in this way form a basis for the development of written language. The teachers in grade 1 describe the work on oral communication and giving the pupils opportunities to take part in planned and structured discussions on a text. The teachers regard taking part in and being given room to talk in a structured discussion as particularly beneficial for the multilingual pupils, a stance that is supported by the research in this field (Damber, Citation2010).

According to the teachers, it is very important, perhaps even essential, that all pupils develop the ability to read and write to be able to take part in society and as a base for continued learning. Teachers’ attitude is characterised by what is usually known as a balanced or integrated stance (Snow & Juel, Citation2005; Taube et al., Citation2015), that is, they draw attention to, evaluate and work with both technical and learning-oriented processes of reading and writing. Getting the pupils to understand how the alphabet system is built-up, so that they can “break the code” (Luke & Freebody, Citation1999) is an important part of the work in grade 1. This is also something that emerges during the interviews, where the teachers talk about the letter of the week and how the link between phoneme and grapheme can be established with the aid of talking keyboards or using signs as a support. For those pupils who risk facing problems in decoding, this early and structured work has proved to be of essential significance (Kamhi & Catts, Citation2014; Snow & Juel, Citation2005; Taube et al., Citation2015).

However, in teachers’ descriptions it is the work that can be connected to phase 2 and 3 in Luke and Freebody’s (Citation1999) model that is given the most room, that is, activities aimed at stimulating the creation of text and understanding of different sorts of text. There are many examples in the interviews of how the teachers work with and support pupils early writing, individually and in pairs. With regard to the perception and understanding of texts, reading aloud is important in grade 1, as many pupils still do not read fluently themselves. To provide the right conditions for the pupils to become text users, they describe a structured form of work on different types of reading strategy and discussions of the texts. For pupils who do not have Swedish as their first language, these discussions are regarded as particularly important, as they provide scope for explaining concepts and words in the stories. These discussions can also be regarded as a first step towards the fourth and final phase which concerns being able to analyse texts.

Similar to an earlier study of how teachers in grade 1 work to encourage pupils written language developments (Sandberg et al., Citation2015), the teachers in this study talk about a pluralistic approach to different methods and ways of working. According to the teachers, the learning process is different for different pupils and therefore there needs to be a variation in the methods and ways of working. Something that the teachers emphasise is that the instruction must be based on where the individual pupils are in their own learning process, and this applies in particular to pupils who do not have Swedish as their first language. To survey the pupils’ reading and writing processes and to plan individualised instruction the teachers use different types of tool as described above, both quantitative and qualitative. With regard to pupils with another mother tongue then Swedish, they talk about the value of collaboration with the parents to be able to assess the pupils’ development in his or her different languages. When it comes to the problems identified by, for instance, Hedman (Citation2009) with regard to pupils with another first language running the risk of not receiving adequate support for their problems in reading and writing or alternatively no support at all, methods that detect the problems in reading and writing at an early stage are extremely important. In addition to collaboration with parents, the research (for instance, Elbro, Daugaard, & Gellert, Citation2012; Hedman, Citation2009) emphasises that mother tongue teachers should take part in surveying the development of reading and writing and helping to identify causes to obstacles arising in this field. There was no mention in the interviews of collaboration with mother tongue teachers with regard to surveying the pupils’ development in reading and writing. This is perhaps not so strange given that the teachers interviewed have classes in grade 1. It is common that the schools wait to survey and investigate possible difficulties in reading until grade 1 is complete (Sandberg et al., Citation2015). Having a good insight into where the pupils are in their learning process is a necessary condition for all instruction, according to Vygotsky (1034/86), and this is something the teachers say they try to achieve. Although the different forms of survey described do not actually say so much about the pupils’ actual development zone (see Hagtvet et al., Citation2016), they nevertheless lay a good foundation for individualising the instruction.

Another dimension of individualised instruction concerns considering and taking into account the pupils’ different interests and cultural experiences. The teachers talk, for instance, about building on the pupils’ understand and working thematically to capture their interest. The fact that the pupils’ different linguistic and cultural experiences are not always taken into account when they start school is illustrated, for instance, in a study by Fast (Citation2007) concerning seven pupils social capital and what significance this has in the context of preschool and school. According to Cummins (Citation2012), instruction that is based on the pupils’ interests and identity creates good conditions for multilingual pupils to learn and develop. Cummins gives examples of how pupils can work with texts in their different languages, identity texts, something he says leads to increased motivation and inclusion. The study does not describe any structured activities of this nature. The few examples given of something similar are that in the classroom they discuss what different things are called in the pupils’ mother tongues. The writing and reading practices described from the classrooms are entirely focussed on Swedish, that the pupils shall be given the chance to meet the knowledge requirements for grade 1 in Swedish and Swedish as a second language. There is a risk that pupils not given the opportunity for parallel use of several languages will abandon the language that is not spoken by their friends and teachers and thus they will not develop their multilingualism (Hyltenstam, Citation2010; Kultti, Citation2014; Snow et al., Citation2005).

Although it appears as though multilingualism in the classroom is regarded as a positive thing by the teachers in the study, it also becomes clear that it is considered a major challenge to meet all of the different conditions, experiences and needs of the pupils. And not least the pupils’ different linguistic backgrounds. Views on and knowledge of multilingualism are important for the conditions created for multilingual pupils to develop their written language (Damber, Citation2009; Dixon & Wu, Citation2014; Ortiz & Fránquiz, Citation2016). The focus group interviews indicate that there is some uncertainty among the teachers as to how to relate to the pupils’ multilingualism in a classroom situation. It is also clear that several of them feel they lack the competence in this field needed to observe and support the learning and development of multilingual pupils.

It may appear to be challenging for a teacher to take into account all of a multilingual child’s languages in his or her instruction, but as Kultti (Citation2014) says, it is not necessary to be able to speak all of the languages. The important thing is the approach of being curious and confirming the child’s linguistic identity and being open to parallel text practices. The conclusions that can be drawn from this study are that the teachers’ attitudes towards linguistic diversity in classrooms can be described as mostly positive. In the group interviews, different teaching strategies emerge to promote the learning of all students. At the same time, uncertainty among teachers is shown in relation to pupils with a mother tongue other than Swedish and what would best support their reading and writing development. Although the teachers are positive about the pupils’ different languages, there is no indication that the different languages spoken by the students are an active part of the reading and writing instruction.

The contribution of this small scale study is the perspectives of teachers with collective experience from working with pupils with diverse linguistic backgrounds. The study is conducted in a qualitative tradition based on focus groups interviews including 17 teachers, of whom 12 are working in grade 1. Thus, the result cannot be generalised to be valid for teachers in general. Still, there are some important findings that can be discussed among practitioners, teacher educators and researchers concerning how teachers in grade 1 talk about and describe their experiences and didactic work to promote optimal conditions for all pupils to learn and develop reading and writing among children with different linguistic backgrounds.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Gunilla Sandberg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8931-7463

References

- Alatalo, T. (2011). Skicklig läs- och skrivundervisning i åk 1-3. Om lärares möjligheter och hinder [Proficient reading and writing instruction in grades 1–3: Teachers’ opportunities and obstacles]. Gothenburg Studies in Educational Sciences 311. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Chang, L. L. S., & Sylva, K. (2015). Exploring emergent literacy development in a second language: A selective literature review and conceptual framework for research. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(1), 3–36. doi: 10.1177/1468798414522824

- Chioncel, N. E., Van Der Veen R. G. W., Wildemeersch, D., & Jarvis, P. (2003). Validity and Reliability of focus groups as a research methods in adult education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 22(5), 495–517. doi: 10.1080/0260137032000102850

- Cummins, J. (2012). The intersection of cognitive and sociocultural factors in the development of reading comprehension among immigrant students. Reading and Writing, 25, 1973–1990. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9290-7

- Damber, U. (2010). Using inclusion, high demands and high expectations to resist the deficit syndrome: A study of eight grade three classes, high achieving in reading. Literacy, 43(1), 43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4369.2009.00503.x

- Damber, U. (2016). Flerspråkiga barns läsundervisning [Teaching literacy to multilingual children]. In I. T. Alatalo (Ed.), Läsundervisningens grunder [Teaching reading] (pp. 215–232). Stockholm: Gleerups.

- Dixon, L. Q., & Wu, S. (2014). Home language and literacy practices among immigrant second-language learners. Language Teaching, 47(4), 414–449. doi: 10.1017/S0261444814000160

- Ehri, L. C. (2005). Development of sight word reading: Phases and findings. In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 135–154). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Elbro, C., Daugaard, H. T., & Gellert, A. C. (2012). Dyslexia in second language? A dynamic test of reading acquisition may provide a fair answer. Annals of Dyslexia, 62(3), 172–185. doi: 10.1007/s11881-012-0071-7

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fast, C. (2007). Sju barn lär sig läsa och skriva. Familjeliv och populärkultur i möte med förskola och skola [Seven children learning to read and write. Family life and popular culture meet preschool and school]. Uppsala Studies in Education, 115. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10. doi: 10.1177/074193258600700104

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Hagtvet, B., Frost, J., & Refsahl, V. (2016). Intensiv läsinlärning [Intensive reading instruction]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Hedman, C. (2009). Dyslexi på två språk. En multipel fallstudie av spansk-svensktalande ungdomar med läs- och skrivsvårigheter [Dyslexia in two languages. A muliple case study of Spanish-Swedish speaking adolescents with reading and writing difficulties]. (Centre for Research on Bilingualism, Doctoral Dissertation). Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Hedman, C. (2012). Läsutveckling hos flerspråkiga elever [Reading Development of Multilingual Students]. In I. E.-K. Salameh (Red.), Flerspråkighet I skolan – språklig utveckling och undervisning [Multilingualism In School - Linguistic Development and Teaching] (pp. 78–97). Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Hyltenstam, K. (2010). Läs- och skrivsvårigheter hos tvåspråkiga [Reading and writing difficulties in bilingual students]. In I. B. Ericson (Red.), Utredning av läs- och skrivsvårigheter [Assessment of reading and writing difficulties] (pp. 305–334). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Kamhi, A. G., & Catts, H. W. (2014). Language and reading: Convergences and divergences. In A. G. Kamhi & H. W. Catts (Eds.), Language and reading Disabilities (pp. 1–23). Boston: Pearson.

- Kultti, A. (2014). Flerspråkiga barns villkor i förskolan – lärande av och på ett andra språk [Multilingual children’s conditions in preschool - learning from and in a second language]. Stockholm: Liber.

- Lipka, O., & Siegel, L. S. (2012). The development of reading comprehension skills in children learning English as a second language. Reading and Writing, 25, 1873–1898. doi: 10.1007/s11145-011-9309-8

- Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). Further notes on the four resources model. Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/research/lukefreebody.html

- Lundberg, I., Frost, J., & Petersen, O.-P. (1988). Effects of an extensive program for stimulating phonological awareness in preschool children. Reading Research Quarterly, 23(3), 263–283. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.23.3.1

- Norling, M. (2015). Förskolan – en arena för social språkmiljö [Preschool – a social language environment and an arena for emergent literacy processes]. (Doktorsavhandling 173). Västerås: Mälardalens högskola.

- Ortiz, A. A., & Fránquiz, M. E. (2016). Co-editors’ introduction: Nuanced understandings of emergent bilinguals and dual language program implementation. Bilingual Research Journal, 39(2), 87–90. doi: 10.1080/15235882.2016.1177778

- Salameh, E.-K. (2012). Flerspråkig språkutveckling [Multilingual language development]. In I. E.-K. Salameh (Red.), Flerspråkighet I skolan – språklig utveckling och undervisning [Multilingualism in school – linguistic development and teaching] (pp. 27–55). Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Sandberg, G., Hellblom-Thibblin, T., & Garpelin, A. (2015). Teacher’s perspective on how to promote children’s learning in reading and writing. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(4), 505–517. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2015.1046738

- Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (Eds.). (2005). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading. Preparing teachers for a changing world. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Snow, C. E., & Juel, C. (2005). Teaching children to read: What do we know about how to do it? In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 521–537). Malden, MA: Blackwell publishing.

- Taube, K., Fredriksson, U., & Olofsson, O. (2015). Kunskapsöversikt om läs- och skrivundervisning för yngre elever [Research overview about teaching and learning for younger students]. Vetenskapsrådets rapporter. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education 2011. Lgr11. (2016). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet [Curriculum for compulsory school, preschool-class and leisure-time center]. Stockholm: The Swedish National Agency for Education.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2017). PM Nyanlända - aktuell statistik November 2015 [PM New arrivals - current statistics November 2015]. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3574. 2017-06-18

- Tjernberg, C., & Heimdahl Mattsson, E. (2014). Inclusion in practice: A matter of school culture. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(2), 247–256. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2014.891336

- UNESCO. (2006). The Salamanca Statement. Retrieved from www.unesco.org. 2016-01-15.

- Vygotsky, L. (1934/1986). Thought and language. (A. Kozulin, Trans. and Ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. (Original work published 1934).

- Wibeck, V. (2000). Fokusgrupper, Om fokuserade gruppintervjuer som undersökningsmetod [Focus groups, about focused group interviews as research method]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.