ABSTRACT

The optimism hypothesis claims that immigrant students do better in the Norwegian education system than their socioeconomic status would suggest, due to the strong educational aspirations that immigrant parents might have for their children. Grounded in an educational equity paradigm, this study aims to test this hypothesis by investigating direct and indirect influences on students’ reading achievement, assessing both how often the students speak the language of instruction, Norwegian, at home; and the effect for students of parents’ educational levels that affect parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework. Using PIRLS 2016 data from Norway (n = 4,232, mean age 10.8), path analysis provided evidence that both students’ home language and parents’ educational level directly influence reading achievement. The mediating roles of parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework on these relationships fluctuated. Thus, the data provided evidence that only partially supports the optimism hypothesis.

1. Introduction

In many Western societies, researchers from a variety of fields have noted a paradox: immigrants’ descendants often achieve good educational attainment and educational degrees even if their families are of low socioeconomic status (SES) (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Hermansen, Citation2016; Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2001; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010). This paradox has challenged traditional reproduction theories from the field of sociology (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Portes et al., Citation2005; Shah et al., Citation2010). Cultural and sociological reproduction theories, which have had enormous impact on research into educational inequality in Europe and the United States (Van de Werfhorst, Citation2010), revolve around the power of structural factors in society and how they manifest themselves in areas such as education. Reproduction theories provide explanations for why socially privileged students receive better grades in school, perform better on standardized tests, and earn higher educational degrees (e.g., Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1977/Citation1990; Espinoza, Citation2007; Kingston, Citation2001). In Norwegian research, this paradox has led to the development of the optimism perspective, hereafter referred to as the optimism hypothesis (Bakken, Citation2003). The optimism hypothesis assumes that in some immigrant families – and more frequently than in Norwegian native families – there exists an “extra educational drive” (Bakken, Citation2003, Citation2016; Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018). More specifically, immigrant parents have stronger educational aspirations for their children compared to non-immigrant parents and are often eager to help their children succeed academically by involving themselves in their children’s schoolwork (Bakken, Citation2016; Leirvik, Citation2014). Furthermore, the extra educational drive is considered a necessity among the child’s extended family and network in order both to succeed in the new country and to climb the social ladder (Bakken, Citation2016; Hermansen, Citation2016). It should be noted that parents’ academic expectations and aspirations are often described collectively or used interchangeably in studies. These terms represent “[t]he degree to which parents presume that their child will perform well in school, now and in the future” (Boonk et al., Citation2018, p. 18). While the empirical link between parents’ educational aspirations and children’s level of academic attainment is well established (Boonk et al., Citation2018), the research does not reveal how parents’ educational aspirations may be associated with family SES and students’ language background. This study redresses this omission by testing the optimism hypothesis against large-scale data by investigating whether parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework mediate the effects of parental education and students’ home language on reading achievement. A mediating model adds valuable knowledge to the optimism hypothesis because it allows the measurement of indirect associations, enabling the researcher to better understand the interplay of the mechanisms involved in the immigrant drive. Although this theory has been used to explain achievement differences between immigrant groups in Norway, particularly in high-school students (e.g., Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018), this study adds value to the field by examining whether the theory explains achievement differences in reading in younger students, particularly 10-year-olds.

While substantial research has been concerned with establishing evidence for the influence of parents’ educational aspirations on academic achievement in relation to a class-based perspective (Hermansen, Citation2016; Leirvik, Citation2014; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010), less effort has been made to establish this connection in the context of educational equity. The current study is grounded in the framework of educational equity described by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in its Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD, Citation2018). Thus, this study considers the notion that potential associations between parents’ educational level, students’ home language, and students’ reading achievement represent inequity in the education system. Given the well-documented empirical relationship between SES and academic achievement as an indicator of educational equity, investigating mediating factors will add knowledge about the mechanisms that may influence this relationship, which in turn is crucial for promoting equity in education.

1.1. Socioeconomic inequality and immigration present a challenge for school systems

One of the concerns in the educational policies among Western and Nordic societies, with their meritocratic values grounded in school models that promote the notions of fairness, inclusion, and equal opportunities for all, is that socioeconomic inequality has been growing (Buchholtz et al., Citation2020; Gustafsson et al., Citation2018, Gustafsson & Hansen, Citation2018). In Norway, for example, income disparities between families increased significantly between 2014 and 2019 (Omholt, Citation2019). Simultaneously, rapid immigration since the second half of the twentieth century has made the student composition of Norwegian schools more linguistically and culturally diverse (Steinkellner, Citation2017). Over the past two decades, the proportion of 6–15-year-olds in Norway with an immigrant background has more than doubled from 6% in 2000 to approximately 16% in 2016 (Sandnes, Citation2017; Steinkellner, Citation2017). At the beginning of 2021, 18.5% of Norway’s total population were immigrants or Norwegian-born to immigrant parents (Statistics Norway, Citation2022 ). When considering the integration of immigrant childrenFootnote1 in the education system, it is important to determine how well these children have done academically. On the educational level, the strength of the relationship between their family’s SES and academic achievement, as well as between language minority speaking children and academic achievement, are important indicators of the equity in a national education system (OECD, Citation2018; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], Citation2018). On the personal level, however, the question becomes whether the children of immigrant parents can achieve intergenerational progress that will enable them to rise from the poor socioeconomic conditions that they may inherit from their parents (Duncan & Trejo, Citation2015).

1.2. Immigrant parents’ educational involvement

In general, immigrant parents tend to be more optimistic about their children’s educational careers and are more likely to maintain high academic aspirations for their children than native-born parents (Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2001; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010). Studies have shown that immigrant parents tend to have a fundamental belief in the importance of education as well as positive attitudes toward school (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2001; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2009). Many immigrant parents translate these educational aspirations into high expectations and encourage their children to make a sustained effort to achieve them (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Leirvik, Citation2010; Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2001). These aspirations are important because parents’ educational aspirations directly and indirectly influence children’s levels of attainment (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Hermansen, Citation2016; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010). A plausible explanation for the strong educational aspirations among some immigrant parents may be their desire to have their children rise above their family’s SES (Duncan & Trejo, Citation2015). Although immigrant families bring remarkable strengths and optimism, many immigrant children also face a range of challenges associated with immigrating to a new country, including the power of structural factors – lower levels of SES – and the challenges of learning a new language (Cummins, Citation2015; OECD, Citation2019; Portes et al., Citation2005; Portes & Rumbaut, Citation2001). These stressors complicate immigrant students’ adjustment to schools and community settings.

1.3. The relationships between parental education, students’ home language, and reading achievement

The positive statistical relationship between family SES and students’ academic achievement in general, and reading achievement in particular, is well established in empirical research (Broer et al., Citation2019; Sirin, Citation2005; Thomson, Citation2018; White, Citation1982). There is also evidence that there are substantial differences in primary school students’ reading comprehension levels according to their social group (Buckingham et al., Citation2013). The influence of family SES on academic achievement varies across school systems, SES measures, and measures of academic achievement (Broer et al., Citation2019; Sirin, Citation2005; Van Ewijk & Sleegers, Citation2010). The correlation between students’ academic achievement and family SES is around .20 – .40 in most countries (Sirin, Citation2005). Although attainment studies based on large-scale assessments have found the SES-achievement relationship to be less pronounced in Norway (and in the other Nordic countries: Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland) than in other OECD countries, this relationship is still substantial (Gustafsson & Hansen, Citation2018; Mittal et al., Citation2020; OECD, Citation2018). Within the threefold socioeconomic index, the cultural dimension has been found to have the strongest influence on school achievement, particularly on literacy (Buckingham et al., Citation2013; Cheadle, Citation2008; Rodríguez-Hernandez et al., Citation2020). One reason for this may be the relationship between literacy and several aspects of SES (Erola et al., Citation2016). For example, parental education is associated with the cultural resources available to the family, such as books in the family home (Strand & Schwippert, Citation2019), early literacy activities (Hemmerechts et al., Citation2016; Myrberg & Rosén, Citation2009), and a favorable learning environment (Shavers, Citation2007). Moreover, parents who promote academic values and academic expectations can link schoolwork to their future plans for their children, which can further affect their children’s educational outcomes (Hill & Tyson, Citation2009; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, Citation2015).

Severe challenges have been identified that affect studying the associations between family SES, immigrant children and academic achievement, as well as the influence of their class background on this relationship (Kindt, Citation2017; Leirvik, Citation2014). Methodologically, it is problematic that most studies do not have data on immigrants’ SES level or social standing in their country of origin (Fekjær, Citation2010; Leirvik, Citation2014). The level of SES in their host country and the way SES is measured may fail to capture the actual social, cultural, and economic background of immigrants. Possessions such as books and digital devices (which are common indicators of SES) may not be reported because they were lost in the migration process. Other commonly used SES indicators include income and occupation, but these indicators may not be the best measures of immigrants’ SES because many immigrants must take jobs for which they are overqualified in their new country. Systematic underreporting of real SES among immigrants may bias the results in such a way that the differences between immigrant parents and their children appear to be more substantial than they really are (Fekjær, Citation2010). However, studies in which information about immigrant parents’ SES level in their country of origin is included show that the parents’ involvement in their child’s schoolwork tends to be related to their SES level in their home country (Kindt, Citation2017). For example, Kindt (Citation2017) found in her study of 28 immigrants’ descendants that immigrant parents whose SES was higher in their country of origin than in the host country (Norway) were involved in their children’s schoolwork in a way that was comparable with “typical middle-class behavior” (Kindt, Citation2017, p. 83).

This study uses only parents’ education as an indicator of family SES. The rationale for this is that education is a permanent resource, as it is not something that can be lost on one’s way to a new country; therefore, parents’ education is appropriate as an indicator of SES across ethnic groups. Next, within the socioeconomic index, parents’ education is found to have the strongest influence on school achievement – particularly on reading literacy (Cheadle, Citation2008; Hansen & Gustafsson, Citation2019; Marks, Citation2007; Rodríguez-Hernandez et al., Citation2020). Finally, education is a strong determinant of intergenerational mobility (Hansen & Gustafsson, Citation2019), which is assumed to be the primary motivating force in the optimism hypothesis (Bakken, Citation2003).

Students whose home language is different from the dominant language of instruction at school face the dual challenge of developing reading skills in their second language while also acquiring the language in which such skills are taught (August & Shanahan, Citation2008). Differences in reading achievement in standardized test scores between students who regularly speak the language of instruction at home and students who speak the language of instruction less frequently at home are pronounced in both Progress in International Reading Literacy (PIRLS) (Mullis et al., Citation2017) and PISA (OECD, Citation2018). These differences are also evident in Norway, although they are smaller there than in many other countries (Jensen et al., Citation2020; Strand et al., Citation2017). On average, in PIRLS 2016, students who claimed that they never spoke Norwegian at home lagged 30 points behind students who claimed that they always spoke Norwegian at home (Strand et al., Citation2017, p. 79). Strand and Schwippert (Citation2019) found a statistically significant – albeit small – association between students’ home language and reading achievement after controlling for other home literacy resources and parents’ educational levels (β = −.15). However, despite the statistical relationship between students’ home language and academic achievement (favoring students who more frequently speak the language of instruction at home), more than 30 years of research have documented that language differences between home and school cannot themselves explain the empirical data (e.g., Cummins, Citation2011; Goetry et al., Citation2006; Melby-Lervåg & Lervåg, Citation2011). In other words, the fact that students come from a background in which the language of instruction is not their dominant language cannot be seen as a causal explanation for achievement differences between language-minority students and students who are native speakers (Cummins, Citation2015). One of the commonly emphasized reasons for this is that language differences between home and school intersect with family SES (Cummins, Citation2015; Sirin, Citation2005). In Norway, research has provided contradictory results regarding how well immigrant children perform in school. On the one hand, children of immigrant parents and language-minority students do not tend to perform as well as their non-immigrant peers in school (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Jensen et al., Citation2020; Strand & Schwippert, Citation2019); moreover, fewer immigrant students than non-immigrant students complete upper secondary school (Steinkellner, Citation2017). On the other hand, many immigrant children are found to have high academic aspirations, and as a group, they put more effort into schoolwork than the average ethnically Norwegian student does (Bakken, Citation2016; Hermansen, Citation2016). In the last few years, immigrant students have been found to be overrepresented in higher education in Norway (Steinkellner, Citation2017, Citation2020).

1.4. Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement

According to Grolnick and Slowiaczek (Citation1994), parental involvement in children’s schooling refers to the economic and psychological resources parents invest in their children’s schooling, broadly defining it as “[t]he dedication of resources by parent to the child” (p. 238). Others have given more specific definitions describing parental involvement as parental activities at home and at school that are related to children’s learning in school (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1997). Rather than giving a general definition of parental involvement, this study focuses on two specific types of parental involvement: parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework. Despite different conceptualizations and measurements of parental involvement, prominent meta-analyses in the field agree on a positive statistical relationship between parental involvement and academic achievement (e.g., Boonk et al., Citation2018; Broer et al., Citation2019; Castro et al., Citation2015; Fan & Chen, Citation2001; Hattie, Citation2009; Hill & Tyson, Citation2009; Jeynes, Citation2007; Shute et al., Citation2011; Wilder, Citation2014). Most studies investigating the relationships between parental involvement and reading achievement for elementary school children reported small to moderate positive associations between parental involvement and reading achievement (Boonk et al., Citation2018; Hill & Tyson, Citation2009).

However, it should be noted that empirical research does not draw a uniform picture indicating which specific types of parental involvement are the strongest determinants of achievement. In their meta-analysis of 13 studies, Sénéchal and Young (Citation2008) examined the relationship between parental involvement and the acquisition of literacy from kindergarten to third grade. According to their study, parental involvement included parents reading to their children, parents listening to their children read, and parents completing literacy exercises with their children. Despite the different effects between different types of parental involvement, the overall results of this meta-study concluded that parental involvement positively influenced reading acquisition, and these findings were consistent across SES levels. Boonk et al. (Citation2018) identified four aspects of parental involvement as promising determinants for academic achievement: reading with children at home, parents having high expectations for their child’s academic achievement, communication between the parents and child about school, and parental encouragement and support for learning. Among the different aspects of parental involvement, this meta-study found academic expectations to have the strongest effect on academic achievement. This result aligns with several other meta-studies that have found parents’ expectations and aspirations to be some of the strongest family predictors of children’s academic achievement in general and of reading achievement specifically (Buckingham et al., Citation2013; Castro et al., Citation2015; Jeynes, Citation2007).

While a substantial body of research has investigated the influence of parental involvement on reading achievement (Buckingham et al., Citation2013; Sénéchal & LeFevre, Citation2006; Sénéchal & Young, Citation2008), fewer studies have explored parental involvement as the mediating factor through which achievement takes place (Gustafsson et al., Citation2018; Myrberg & Rosén, Citation2009). Myrberg and Rosén (Citation2008) investigated mediating factors of parents’ education (as an SES indicator) on students’ reading achievement in seven countries, including Norway. Despite variations in effect estimations across countries, they found that having a home library, early reading activities, and early reading abilities mediated the relationship between parental education and reading achievement on the 2001 PIRLS assessment. In a later study, Myrberg and Rosén (Citation2009) found that the number of books in students’ homes, early reading activities, and early reading abilities mediated the relationship between parental education and reading achievement on the 2001 PIRLS assessment for third graders in Sweden. In their study of a French sample, Tazouti and Jarlégan (Citation2016) found that the construct of parental involvement (i.e., parents helping with homework, parents talking about school with their child, and parents participating in the life of the school) and the construct of parental aspirations and expectations mediated the association between family SES and academic achievement, as measured through their achievement in the subjects of French and mathematics.

1.4.1. Parental academic expectations and academic achievement

As previously stated, parental academic expectations and aspirations can be described as “[t]he degree to which parents presume that their child will perform well in school, now and in the future” (Boonk et al., Citation2018, p. 18). Numerous studies have found that children perform better in school, earn better grades, and continue in education longer when their parents have high academic expectations and aspirations than when parents have low expectations and aspirations (Jeynes, Citation2007; Raleigh & Kao, Citation2010). For example, Fan and Chen (Citation2001) found in their meta-analysis that “parents’ aspirations and expectations for children’s educational relationships” have the strongest relationship with students’ academic achievement (overall r = .40). Moreover, the positive effect of parents’ academic expectations on students’ academic achievement was found to be consistent across ethnic groups.

1.4.2. Parents’ help with homework and academic achievement

Prior studies have found the relationship between parents’ help with homework and academic achievement to vary substantially in measurement strength and across different subjects (Boonk et al., Citation2018). Wilder’s meta-synthesis (Citation2014) of the results of nine meta-analyses suggested that there was no positive relationship between parents’ help with homework and students’ academic achievement, causing her to conclude that students are not likely to benefit much from this type of involvement. Some of the inconsistency reported on the “parents’ help with homework / academic achievement” relationship may have to do with how helping with homework was operationalized in the different studies. For example, in the meta-analysis conducted by Patall et al. (Citation2008), the overall effects of parental homework involvement on academic achievement were not significant; however, some of the components of parental involvement in homework did have a strong, positive impact. For instance, enforcing rules about the homework and providing direct help with homework had a positive influence on children’s academic achievement. On the other hand, merely monitoring homework completion had a negative impact on achievement. Tam and Chan (Citation2009) found that the amount of time parents reported spending helping their children with homework to be positively associated with academic achievement in primary schoolchildren. One plausible explanation for why many studies have found a negative correlation between helping one’s children with homework and academic achievement is that elementary schoolchildren who find schoolwork difficult tend to spend more time on their homework, and parents of these children tend to spend more time helping them (Pomerantz & Moorman, Citation2010; Tazouti & Jarlégan, Citation2014). In Norwegian primary schools, parents’ help with homework is one important factor in the school-home collaboration. Since studies have found that immigrant parents in particular tend to have positive attitudes towards school and are involved in their children’s school effort (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018), it was part of this study’s scope to investigate whether some of the effect from students’ home language was mediated through parents’ help with homework.

1.5. The present study

Given that the relationships between SES and student achievement and between students’ home language background and student achievement are important indicators of educational equity (OECD, Citation2018), more knowledge is needed on the mechanisms underlying these relationships, so that educational equity can be promoted. Although researchers have consistently reported the effects of these two types of relationships, the process by which parental education and students’ home language influence student achievement is not well understood. That is, in addition to their direct effects on academic achievement, it is conceivable that the impact of parental education and home language on reading scores might include indirect effects as well. To contribute to this research field, two aims were set for this study: (1) to test the optimism hypothesis and (2) to establish the evidential associations in the context of educational equity as defined by the OECD’s PISA framework (OECD, Citation2018). Specifically, the research question was as follows:

What are the direct and indirect associations between students’ home language, parents’ education, parents’ academic expectations, parents’ help with homework and reading achievement?

To obtain new perspectives on parental involvement, a path model was developed. In contrast to conventional regression analysis, one of the many advantages of path analysis is that it simultaneously considers multiple dependent and independent variables and allows the investigation of models with direct, indirect, or reciprocal effects (e.g., Geiser, Citation2013, p. 62).

2. Methods

2.2. Data and sample

The current study relies on data from the Norwegian PIRLS 2016 cycle (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Citation2016).Footnote2 PIRLS assesses reading comprehension in 10-year-olds every five years and provides extensive information about students’ home and school contexts, as well as information about parental involvement in the students’ homes. The assessment design is described in the PIRLS 2016 Assessment Framework (Mullis & Martin, Citation2015).

The student sample in Norway consisted of 4,232 fifth graders (average age: 10.8 years) from 215 classes in 150 schools. PIRLS employs a stratified two-stage random sample design, with a sample of schools drawn as a first stage and intact classrooms of students selected from the sampled schools as a second stage (LaRoche et al., Citation2017). The instruments applied in the current study were PIRLS reading tests, a student questionnaire, and a parent questionnaire. The overall rate of student and parent participation was 95% and 96%, respectively (Gabrielsen & Strand, Citation2017). In total, the sample selection process ensured a representative sample of Norwegian fifth graders. The Norwegian data collection procedures are described in detail in Gabrielsen and Strand (Citation2017). According to the data, of the sample, 50.2% were girls, 67% always spoke Norwegian at home, 21% almost always spoke Norwegian at home, 11% sometimes spoke Norwegian at home, and 1% never spoke Norwegian at home. In approximately 32% of the families, at least one of the parents held a university degree; in only 5% of the families did one or both of the child’s parents report no schooling or having completed only primary school. In addition, students who did not primarily speak Norwegian at home were more likely to come from homes where the parents had low levels of education, compared to their peers who always spoke Norwegian at home. For example, only 1% of the parents whose children never spoke Norwegian at home held a master’s or doctoral degree, compared to 60% of the parents in homes where they always spoke Norwegian.

Missing data at the item level was addressed using a multiple imputation (MI) method, generated from a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation in Mplus version 8.8 (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2022). Specifically, Mplus runs 100 MCMC iterations and then stores the generated missing data values. This process is repeated until the desired number of imputations have been stored (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2022, p. 2). The data set applied in this study was estimated in Mplus using the Bayesian estimation technique (see, Enders, Citation2010). Specifically, this means that the software uses the interrelations between the x-variables and all the available information of cases to impute (i.e., fill in) the missing values.

Analysis of imputed data is considered equivalent to FIML (full information maximum likelihood) analysis of the raw imputed data (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2022, p. 24). One reason that justifies using MI is that the PIRLS dataset contains many variables, but for the present study only a small subset of variables was of interest. In a case like this it is useful to impute the data from a large set and use the imputed data set with the variable subset. This way we limit the risk of excluding an important missing data predictor (see, Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2022). All the variables used in the current study were included in the imputation procedure. However, handling missing data using MI can be intricate, particularly for large multivariate datasets that include a combination of categorical and continuous variables. Therefore, descriptive statistics (cross tabulations) and the path model in the present study were also run on an unimputed dataset (non-imputed values on item-level) using estimator = ML for the path analysis in Mplus. Neither the descriptive statistics nor the model results emerged as significantly different from the imputed dataset, meaning that this study’s conclusion holds across the two datasets, regardless of MI.

Since plausible values were provided for students’ reading achievement, multiple imputation was not needed for this outcome variable. PIRLS measured students with only a subset of the item pool designed for group-level estimation. A plausible value approach was used to obtain unbiased group-level estimates; thus, the five plausible values should not be analyzed as multiple indicators of the same score or latent variable (Von Davier et al., Citation2009). Therefore, five imputed datasets with no missing values were generated, combining each with one plausible value; the applied sample size in the current study consisted of 4,231 cases. One student was omitted from the dataset because of a lack of background information.

2.2. Measures

Students’ overall reading achievement scale (ASRREA01-05/Overall Reading in the dataset), which constitutes a total score of the students’ reading proficiency (for technical details, see TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Citation2017), was the dependent variable in the model. Cronbach’s alpha test reliability coefficient for the PIRLS’s overall reading achievement scale for Norway 2016 was .87 (Foy et al., Citation2017, Exhibit 10.7). The coefficient is the median Cronbach’s alpha reliability across all PIRLS 2016 assessment booklets.

Students’ home language (ASBG03 in the data set) had the following wording: “How often do you speak Norwegian at home?” The students responded using a four-point Likert-type scale where the options were as follows: 0 = I always speak Norwegian at home; 1 = I almost always speak Norwegian at home; 2 = I sometimes speak Norwegian at home; and 3 = I never speak Norwegian at home. This means that the larger the value, the less often the student speaks Norwegian at home.

Parents’ educational level was measured by two items retrieved from the parents’ questionnaire: “What are the highest levels of education completed by (A) the child’s father (or stepfather or male guardian) [ASBH18A in the dataset] and (B) the child’s mother (or stepmother or female guardian)?” [ASBH18B in the data set]. A new variable was computed, including only the score of the parent with the highest education level. The education levels in the response categories were based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011, which yielded nine education levels ranging from “did not go to school” to “Doctoral degree.” (Eurostat, Citation2018). Sparse information on some of the response categories made it necessary to merge categories for the multiple imputation model to proceed. ISCED levels 1, 2, and 3 were merged into 0 = completed primary school, ISCED levels 4, 5, and 6 were merged into 1 = completed upper secondary school and 2 = completed bachelor’s degree, and ISCED levels 7 and 8 were merged into 3 = completed a master’s or doctoral degree.

PIRLS includes two indicators for parental involvement, both retrieved from the parents’ questionnaire: parents’ expectations for their child’s educational achievement and parents’ help with homework. Regarding the latter, the following item was applied in this study: “How often do you or someone else in your home help your child with homework?” (ASBH08BB in the data set). The response rates on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranged from 0 = never or almost never to 4 = every day. Parents’ academic expectation had the following wording: “How far in his or her education do you expect your child to go?” (ASBH19 in the data set). In line with the Norwegian Standard Classification of Education (Statistics Norway, Citation2017), the response categories were recoded from six to five categories: 0 = finish primary school (ISCED level 2), 1 = finish upper secondary school (ISCED level 3), 2 = finish a university degree of less than 3 years (ISCED levels 3 and 4), 3 = finish a bachelor’s degree (ISCED level 6), and 4 (ISCED levels 7 and 8) = finish a master’s or doctoral degree.

2.3. Statistical analyses

A path model was applied to examine structural relationships among the two exogenous variables (i.e., student’s home language and parents’ educational level), the two endogenous variables (i.e., parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework), and the ultimate dependent variable (i.e., students’ reading achievement). The errors between the variables parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework were let to correlate in the model.

Indirect associations were tested using the model indirect subcommand in Mplus (Kelloway, Citation2015, pp. 106–107). The significance of the indirect associations was tested by applying the bias-corrected bootstrap method (MacKinnon, Citation2008). Specifically, 1,000 bootstraps and 95% confidence intervals were applied. In PIRLS, sampling weights were used to accommodate the fact that some units (schools, teachers, or students) were selected with different probabilities; thus, appropriate weights need to be applied in analyses on PIRLS data (Rutkowski et al., Citation2010). House weight, which ensures that the weighted sample corresponds to the actual sample size, was applied to the current analysis (Stapleton, Citation2010, pp. 363–384). The intraclass correlation (ICC) for reading achievement was calculated, as the ICC measures the degree of dependence of observations. Cluster effects were accounted for by using school identification (IDSCHOOL) as a cluster option. As ignoring the use of the dataset’s plausible values would produce biased results (Von Davier et al., Citation2009), all five plausible values of the overall reading literacy scale were included in the calculations to yield one single result.

Descriptive statistics, correlations and path analysis were calculated in Mplus version 8.8. The IEA International Database Analyzer 5.0.5 was utilized to merge the data files of students’ reading results, parent questionnaires, and student questionnaires. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used to prepare the data.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and preliminary results

Cross-tabulation analyses were conducted to display the interrelationships between parental education, students’ home language, parental academic expectations, and parents’ help with homework. Regarding the relationship between parents’ educational level and how much time they spent helping their children with homework, the cross-tabulation revealed that most parents stated that they help their child with their homework. Only 1.5% of the parents stated that they never or almost never help their child with homework. One interesting result was that 32% of the parents with the lowest level of education (completed primary school) said that they helped their children with homework every day, compared to 20% of the parents with the highest level of education (a master’s or doctoral degree). Indeed, parents with the highest educational level were the least likely of all parents to help their children with homework most frequently (see ).

Table 1. How often parents help their child with homework by parents’ level of education.

Regarding the relationship between the time parents spent helping their children with homework and students’ home language, the cross-tabulation showed some variance between the groups regarding how often parents help with homework. For example, approximately 23% of the parents whose child always speaks Norwegian at home said that they’d help with homework every day, compared to 33% of the parents whose child sometimes speaks Norwegian at home. Approximately 7% of the parents whose child always speaks Norwegian at home said that they’d help with homework less than once a week, compared to 13% of the parents whose child sometimes speaks Norwegian at home (see ).

Table 2. How often parents help their child with homework by the students’ home language.

When it comes to the relationship between parental education and parental expectations, cross-tabulations showed that parents with the highest level of education had the highest expectations for their child. Specifically, 57% of parents who held a master’s or doctoral degree expected their child to reach one of these same academic levels, whereas only 12% of parents with secondary school as their highest educational level expected their children to reach master’s or doctoral level (see ).

Table 3. Parents’ academic expectations by level of their education.

Parents of children who sometimes or never spoke Norwegian at home had the highest expectations for their children’s academic career. More precisely, 41% of parents whose children never spoke Norwegian at home, and 45.5% of the parents whose children sometimes spoke Norwegian at home, said that they expected their children to earn a master’s or doctoral degree, compared to 26% of the parents whose children always spoke Norwegian at home (see ).

Table 4. Parents’ academic expectations by the students’ home language.

3.2. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and other correlations

In the PIRLS data, students are clustered in classes, and classes in schools. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the overall reading achievement was on school level 0.11, implying that 11% of the observed variance in student reading achievement can be attributed to systematic differences between schools. However, the research question in the present study focuses on the general effects in the observed population and not on average school effects. Hence, the path-model was conducted on student level, accounting for any clustering effects.

Next, the mean, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations among the variables in the study were calculated. The results are shown in .

Table 5. Correlation matrix for study variables.

3.3. Structural relations in path analysis

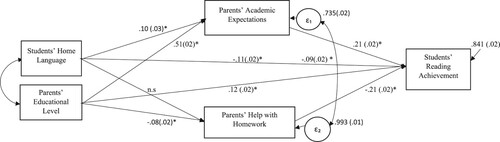

The standardized estimates were as follows. As expected, parental education was significantly and positively associated with reading achievement (β = .12, p < .001) and with parents’ academic expectations (β = .51, p < .001). Further parental education was significantly and negatively associated with parents’ help with homework (β = - .08, p < .001).

As expected, student’s home language had a significant and negative association with reading achievement (β = −.11, p < .001), meaning that the less Norwegian the students speak at home, the lower their reading scores on the PIRLS test. This variable was also significantly and positively associated with parents’ academic expectations (β = .10, p < .001), but there was no significant association between students’ home language and parents’ help with homework.

Parents’ academic expectations were significantly and positively associated with reading achievement (β = .21, p < .001). Parents’ help with homework was significantly and negatively associated with reading achievement (β = −.21, p < .001).

To estimate the indirect associations, the bias-corrected confidence intervals were included in the calculations. The following results are stated in standardized estimates. The indirect association between parental education and reading achievement through parental academic expectations was significant, albeit small (β = 0.11, 95% CI [.086, .132], p < .001). The indirect association between parental education and reading achievement through parents’ help with homework was also significant though small (β = 0.02, 95% CI [.009, .027], p < .001). The results further show a weak indirect association between students’ home language and reading achievement through parental academic expectations (β = 0.02, 95% CI [.010, .032], p < .001). The indirect association between students’ home language and reading achievement through parents’ help with homework was not significant. For the sake of clarity, shows the direct, indirect, and total effects on reading achievement produced by parental education, students’ home language, parents’ academic expectations, and parents’ help with homework.

Table 6. Direct, indirect, and total effects of parental education, students’ home language, parents’ academic expectations and parents’ help with homework on reading achievement.

Finally, approximately 27% (R2 = .265) of the variability in parents’ academic expectations, approximately 0.7% (R2 = .007) of the variability in parents’ help with homework, and approximately 16% (R2 = .159) of students’ reading achievement can be explained. displays the results of the structural relationships.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated direct and indirect associations of students’ home language, parents’ educational level, parents’ academic expectations, and parents’ help with homework with students’ reading achievement in PIRLS, using a representative sample of 4,231 Norwegian fifth graders. Most of the associations tested were significant even though they were relatively weak. The results will now be discussed according to the two aims of this study, which were (1) to test the optimism hypothesis and (2) to establish the evidential associations in the context of educational equity as defined by the OECD’s PISA framework (OECD, Citation2018).

The findings in the current study must be interpreted in the context of Norway’s 100-year tradition of unitary school for all, with its main goal of equalizing social differences and its meritocratic approach to educational equity (Buchholtz et al., Citation2020). Moreover, since the beginning of Norway’s immigration history in the late 1960s, a substantial proportion of immigrants who have settled there came because of work opportunities, particularly jobs related to the oil and gas industry (Statistics Norway, Citation2022, march 7). Despite increasing economic differences between households and increased immigration, Norway is still a comparatively egalitarian society with a relatively even distribution of income, resources, and a strong welfare system (Buchholtz et al., Citation2020).

The impact of family education on students’ outcomes has long been established as an important indicator of the degree of equity in school systems (Hansen & Gustafsson, Citation2019). As expected, this association was also confirmed in this study; however, it should be noted that the relatively weak association between parental education and reading achievement in this data may indicate a low degree of inequity regarding reading literacy. Previous research has indicated an association between a student’s home language and reading achievement (Agirdag & Vanlaar, Citation2016; Heppt et al., Citation2015). Those studies found that when the language of instruction is less spoken at home, students’ reading scores are lower. This result was also evident in this study; however, the strength of this association was small. This might be affected by a methodological issue and the fact that students who had received Norwegian language training for less than a year were excluded from the PIRLS assessment (Gabrielsen & Strand, Citation2017). It is worth considering whether this exclusionary practice in the sampling procedures may create bias in the results, causing the associations to appear smaller than they really are.

Next, the results also showed that the level of parents’ academic expectations is generally higher for well-educated parents than for parents with low educational levels. This is also in line with previous research (Leirvik, Citation2014; Tazouti & Jarlégan, Citation2014). The indirect associations running from parental education through parents’ academic expectations on reading achievement were also significant and indicate that a substantial part of the total effect of parents’ level of education on students’ reading achievement is mediated by parents’ academic expectations.

A positive association was found between students’ home language and parents’ academic expectations. Several other Norwegian studies have found immigrant parents to have higher expectations of their children’s future school career than native-Norwegian parents (Bakken, Citation2016; Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018; Lauglo, Citation1999). These findings have sometimes been interpreted as suggesting that some immigrant families have a strong desire for social mobility (Bakken, Citation2016; Leirvik, Citation2014). In educational research, this view is referred to as the optimism hypothesis and has been used to explain why a large proportion of students with an immigrant background perform well academically in Norway despite their low SES (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018). This hypothesis marks an interesting contrast to reproduction theories that claim that “schools are not transmitters of opportunities but active agents of social reproduction” (Kingston, Citation2001, p. 88). In contrast, according to this optimistic view, immigrant students from low SES backgrounds can succeed academically under the right circumstances, and studies have shown that parental expectations are one of the determinants of the relationship between SES and achievement (Bakken & Hyggen, Citation2018).

The findings in this study partly support this idea. Regarding the weak association between students’ home language (which indicates that their family has some kind of immigrant background) and parental expectations, and the strong association between parents’ educational level and parents’ academic expectations, it may be that strong educational aspirations are more closely linked to the family’s SES than to the student’s language background. The fact that the academic success of children from well-educated homes may, to some extent, be attributable to the expectations of their parents resonates well with cultural reproduction theory: according to Bourdieu, well-educated parents transfer their preferences to their children and invest time and involvement in their children to ensure that they will succeed in school (Bourdieu, Citation1986; Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1977/Citation1990). Therefore, children’s reading achievement can be described as manifestations of the reproduction of cultural capital within families because cultural reproduction theory argues that well-educated parents pursue their own academic aspirations through academic expectations. In other words, it appears that parents’ educational level is more important than language background regarding parents’ academic expectations as a determiner of reading achievement. This indicates that it is probably not the children’s language background that generates parents’ high expectations; instead, it is their socioeconomic background. Thus, the results from this study provide clearer evidence for the cultural reproduction theories than for the optimism hypothesis.

The association between parents’ educational level and parents’ help with homework was found to be significantly negative. One possible explanation for the negative association may be that students coming from well-educated homes tend to have a more school-like home culture with access to pedagogical resources, such as books, games, computers, etc. Children who grow up in an environment that promotes learning are better able to academically self-regulate and therefore need less help with their homework (e.g., Hill & Tyson, Citation2009). The negative association between parents’ help with homework and reading achievement, which is in line with much previous research (Boonk et al., Citation2018), was therefore not unexpected. Several theoretical explanations for why there seems to be a negative association between parents’ help with homework and reading achievement have been offered. One suggests that students are not very likely to benefit much from this type of parental involvement (Wilder, Citation2014), whereas others have argued that children who struggle with their schoolwork also get more help from their parents (and, as a corollary, more adept students do not need their parents’ help to the same extent) (Pomerantz & Moorman, Citation2010; Tazouti & Jarlégan, Citation2014). Finally, a small but significant effect runs from parents’ educational level through parents’ help with homework on to reading achievement; however, no significant indirect effect was found between students’ home language through parents’ help with homework on reading achievement. Again, this points to the conclusion that the family’s education level is more important for parental involvement in children’s schoolwork than the family’s language background.

5. Limitations and future research

This study adopted a cross-sectional design, meaning that causal inferences concerning the hypothesized relationships cannot be drawn. Nevertheless, the large sample size is a strength of the study, as it enabled the findings to be generalized. The 2016 PIRLS assessment did not provide additional information about students’ specific geographic backgrounds. Thus, it was not possible to consider individual differences, such as the different types of ethnic or linguistic groups that might account for some variability in the data. Students who do not speak Norwegian as their primary language were of particular interest in the present study. However, students who had received training in the Norwegian language for less than a year were excluded from the PIRLS assessment. This constituted a limitation for the study because greater equity in education can be achieved only when the data collected include the most marginalized student groups (UNESCO, Citation2018). To further understand the interplay between different students’ characteristics, parental involvement, and reading achievement, future research should aim to analyze datasets in which information about geographical origins is available. In this study, the optimism hypothesis was assessed with path-analytic techniques, specifically with a mediating model. This methodological approach has its limitations, and future research might consider moderation analysis to extend the knowledge on the mechanisms behind the optimism perspective.

6. Conclusion and implications

The results of this study indicate that parents’ academic expectations play a mediating role in the association between students’ home language and reading achievement as well as between parental education and reading achievement. A weak but significant indirect effect was found between parental education and reading achievement through parents’ help with homework, but not on the relationship between students’ home language and reading achievement. Thus, these results partly support the optimism hypothesis and suggest some degree of educational inequity regarding reading literacy in Norwegian fifth graders.

This study has several implications. First, parents should be aware of the positive impact that academic expectations have on reading, because parental involvement that links children’s schoolwork and future academic goals seems to be associated with achievement in middle school (Hill & Tyson, Citation2009). Regardless of the family’s educational level or the language spoken at home, high parental expectations of children’s academic development can positively influence the children’s reading achievement. However, efforts designed to reduce achievement disparities through parental involvement may achieve limited success because the quality of parental involvement is probably unequally distributed across different family backgrounds. Thus, schools and teachers should be aware of the different types of parental involvement and their varying effectiveness on reading achievement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In the current study, the terms “children with an immigrant background” and “immigrant children” refer to children born in the country to two parents born abroad, and children not born in the host country with both parents born abroad. Many immigrant children also fell into the category “language minority students,” which refers to students whose home language is different from the dominant language of instruction in school.

2 The PIRLS international database is publicly available at https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-database/index.html.

References

- Agirdag, O., & Vanlaar, G. (2016). Does more exposure to the language of instruction lead to higher academic achievement? A cross-national examination. International Journal of Bilingualism, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/136700691665871

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2022). Multiple imputation with mplus (Version 4) [Statmodel.com]. https://www.statmodel.com/download/Imputations7.pdf

- August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2008). Developing reading and writing in second-language learners: Lessons from the repoart of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bakken, A. (2003). Minoritetsspråklig ungdom i skolen Reproduksjon av ulikhet eller sosial mobilitet? [Language minority speaking youth in school reproduction of differences or social mobility?]. Norsk institutt for fforskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring, NOVA Rapport 15/2003.

- Bakken, A. (2016). Endringer i skoleengasjement og utdanningsplaner blant unge med og uten innvandringsbakgrunn. Trender over en 18-årsperiode [Changes in school engagement and educational plans in young people with and without an immigrant background. Trends over an 18-year period]. Tidsskrift for Ungdomsforskning, 16(1), 40–62. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/ungdomsforskning/article/view/1590

- Bakken, A., & Hyggen, C. (2018). Trivsel og utdanningsdriv blant minoritetselever i videregående Hvordan forstå karakterforskjeller mellom elever med ulik innvandrerbakgrunn [Well-being and educational aspirations among minority students in upper secondary school. How to understand grade differences between students with different migration backgrounds?]. Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring, NOVA Rapport 1/2018.

- Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (R. Nice, Trans.). Sage Publications in association with Theory Culture & Society, Department of Administrative and Social Studies, Teeside Polytechnic. (Original work published 1977)

- Broer, M., Bai, Y., & Fonseca, F. (2019). Socioeconomic inequality and educational outcomes. Evidence from twenty years of TIMSS. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-11991-1

- Buchholtz, N., Stuart, A., & Frønes, S. T. (2020). Equity, equality and diversity: Putting educational justice in the nordic model to a test. In S. T. Frønes, A. Pettersen, & J. Radišić (Eds.), Equity, equality and diversity in the nordic model of education: Contributions from large-scale studies (p. 13–41). Springer.

- Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Australian Journal of Education, 57(3), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113495500

- Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martin, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

- Cheadle, J. E. (2008). Educational investment, family context, and children’s math and reading growth from kindergarten through the third grade. Sociology of Education, 81(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070808100101

- Cummins, J. (2011). The intersection of cognitive and sociocultural factors in the development of reading comprehension among immigrant students. Reading and Writing, 25(8), 1973–1990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-010-9290-7

- Cummins, J. (2015). Language differences that influence reading development: Instructional implications of alternative interpretations of the research evidence. In P. Afflerbach (Ed.), Handbook of individual differences in reading reader, text, and context (pp. 223–244). Routledge.

- Duncan, B., & Trejo, S. J. (2015). Assessing the socioeconomic mobility and integration of U.S. immigrants and their descendants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657(1), 108–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214548396

- Enders, K. C. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Publications.

- Erola, J., Jalonen, S., & Lehti, H. (2016). Parental education, class and income over early life course and children’s achievement. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 44, 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.01.003

- Espinoza, O. (2007). Solving the equity-equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educational Research, 49(4), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880701717198

- Eurostat. (2018). International standard classification of education (ISCED). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/International_Standard_Classification_of_Education_(ISCED)#Implementation_of_ISCED_2011_.28levels_of_education.29

- Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009048817385

- Fekjær, S. N. (2010). Klasse og innvandrerbakgrunn: to sider av samme sak? [Social class and immigrant background: two sides of the same coin?]. In I. K. Dahlgren & J. Ljunggren (Eds.), (Klassebilder: Ulikhet og sosial mobilitet i Norge [Class photoes: Inequality and social mobility in Norway] (pp. 84–97). Universitetsforlaget.

- Foy, P., Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., & Yin, L. (2017). Reviewing the PIRLS 2016 achievement item statistics. In M. O. Martin, I. V. S. Mullis, & M. Hooper (Eds.), Methods and procedures in PIRLS 2016 (pp. 10.1–10.26). Timss & PIRLS International Study Center. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/publications/pirls/2016-methods/chapter-10.html

- Gabrielsen, E., & Strand, O. (2017). Rammer og metoder for PIRLS 2016 [Frameworks and methods for PIRLS 2016]. In E. Gabrielsen (Ed.), Klar framgang! Leseferdighet på 4. og 5. trinn i et femtenårsperspektiv [Clear progress! Reading skill in years 4 and 5 from a 15-year perspective] (pp. 13–31). Universitetsforlaget. http://www.idunn.no/klar-framgang/1-rammer-og-metoder-for-pirls-2016

- Geiser, C. (2013). Data analysis with MPlus. The Guilford Press.

- Goetry, V., Wade-Woolley, L., Kolinsky, R., & Mousty, P. (2006). The role of stress processing abilities in the development of bilingual reading. Journal of Research in Reading, 29(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2006.00313.x

- Grolnick, W., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65(1), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131378

- Gustafsson, J.-E., & Hansen, Y. K. (2018). Changes in the impact of family education on student educational achievement in Sweden 1988–2014. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306799

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Nilsen, T., & Hansen, Y. K. (2018). School characteristics moderating the relation between student socio-economic status and mathematics achievement in grade 8. Evidence from 50 countries in TIMSS 2011. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 57, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.09.004

- Hansen, Y. K., & Gustafsson, J.-E. (2019). Identifying the key source of deteriorating educational equity in Sweden between 1998 and 2014. International Journal of Educational Research, 93, 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.09.012

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.13128/formare-13251

- Hemmerechts, K., Kavadias, D., & Agirdag, O. (2016). The relationship between parental literacy involvement, socio-economic status and reading literacy. Educational Review, 69(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1164667

- Heppt, B., Haag, N., Böhme, K., & Stanat, P. (2015). The role of academic-language features for reading comprehension of language-minority students and students from low-SES families. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.83

- Hermansen, A. S. (2016). Moving up or falling behind? Intergenerational socioeconomic transmission among children of immigrants in Norway. European Sociological Review, 32(5), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw024

- Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015362

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543067001003

- Jensen, F., Kjærnsli, M., Björnsson, K. J., & Pettersen, A. (2020). Gir norsk skole alle elever like muligheter til å bli gode lesere? [Do Norwegian schools offer all students equal opportunities to become good readers?]. In S. T. Frønes & F. Jensen (Eds.), Like muligheter til god leseforståelse? 20 years with reading in PISA [Equal opportunities for good reading comprehension? 20 years of reading in PISA] (pp. 222–241). Universitetsforlaget. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215040066-2020

- Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta analysis. Urban Education, 42(1), 82–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085906293818

- Kelloway, E. K. (2015). Using mplus for structural equation modeling. Sage.

- Kindt, T. M. (2017). Innvandrerdriv eller middelklassedriv? Foreldres ressurser og valg av høyere utdanning blant barn av innvandrere [Immigrant aspirations or middleclass aspirations? Parental resources and choice of higher education among children of immigrants]. Norwegian Journal of Sociology, 1, 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1826/ISSN.2535-2512-2017-01-05

- Kingston, P. W. (2001). The unfulfilled promise of cultural capital theory. Sociology of Education, 74, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673255

- LaRoche, S., Joncas, M., & Foy, P. (2017). Sample design in PIRLS 2016. In M. O. Martin, I. V. S. Mullis, & M. Hooper (Eds.), Methods and procedures in PIRLS 2016 (pp. 3.1–3.34). Timss & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). https://pirls.bc.edu/publications/pirls/2016-methods/chapter-3.html

- Lauglo, J. (1999). Working harder to make the grade. Immigrant youth in Norwegian schools. Journals of Youth Studies, 2(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.1999.10593025

- Leirvik, M. S. (2010). For mors skyld: utdanning, takknemlighet og status blant unge med pakistansk og indisk bakgrunn [For mother’s sake: Education, gratitude and status among young people with Pakistani and Indian backgrounds]. Tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning (trykt utg.). 10(1), 23–47. Retrieved from https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/ungdomsforskning/article/view/1046

- Leirvik, M. S. (2014). Mer enn klasse: Betydningen av “etnisk kapital” og “subkulturell kapital” for utdanningsatferd blant etterkommere av innvandrere [More than class: The impact of “ethnic capital” and “subcultural capital” among descendants of Immigrants] [Thesis]. University of Oslo. Retrieved from https://phs.brage.unit.no/phs-xmlui/handle/11250/194540

- MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum.

- Marks, G. (2007). Are father’s or mother’s socioeconomic characteristics more important influences on student performance? Recent international evidence. Social Indicators Research, 85(2), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9132-4

- Melby-Lervåg, M., & Lervåg, A. (2011). Hvilken betydning har morsmålsferdigheter for utviklingen av leseforståelse og dets underliggende komponenter på andrespråket? En oppsummering av empirisk forskning [What significance has native language skills for the development of reading comprehension and its underlying components in the second language? A summary of empirical research]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 95(5), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2011-05-02

- Mittal, O., Nilsen, T., & Björnsson, K. J. (2020). Measuring equity across the nordic education systems: Conceptual and methodological choices as implications for educational policies. In S. T. Frønes, A. Pettersen, J. Radišić, & N. Buchholtz (Eds.), Equity, equality and diversity in the nordic model of education: Countributions from large-scale studies (pp. 43–71). Springer.

- Mullis, V. S. I., & Martin, M. O. (Eds.). (2015). Pirls 2016 assessment framework (2nd ed.). Timss & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

- Mullis, V. S. I., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (Eds.). (2017). International results in Reading. Timss & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College. http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-results/

- Myrberg, E., & Rosén, M. (2008). A path model with mediating factors of parents’ education on students’ reading achievement in seven countries. Educational Research and Evaluation, 14(6), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610802576742

- Myrberg, E., & Rosén, M. (2009). Direct and indirect effects of parent’s education on reading achievement among third graders in Sweden. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 695–711. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909X453031

- OECD. (2018). Equity in education: Breaking down barriers to social mobility. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264073234-en

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume II): Where all students can succeed. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5fd1b8f-en

- Omholt, L. E. (Eds.). (2019). Økonomi og levekår for lavinntektsgrupper [Finances and living conditions in low-income groups] (Vol. 33). Statistics Norway.

- Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1039–1101. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325185

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Moorman, E. A. (2010). Parent’s involvement in children’s schooling: A Context for Children's Development. In J. Meece & J. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 398–417). Routledge.

- Portes, A., Fernandez-Kelly, P., & Haller, W. (2005). Segmented assimilation on the ground: The new second generation in early adulthood. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(6), 1000–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500224117

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant Second Generation. University of California Press.

- Raleigh, E., & Kao, G. (2010). Do immigrant minority parents have more consistent college aspirations for their children? Social Science Quarterly, 91(4), 1083–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00750.x

- Rodríguez-Hernandez, F. C., Cascallar, E., & Kyndt, E. (2020). Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100305

- Rutkowski, L., Gonzalez, E., Joncas, M., & von Davier, M. (2010). International large-scale assessment data: Issues in secondary analysis and reporting. Educational Researcher, 39(2), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X10363170

- Sandnes, T. (2017). Innvandrere i Norge 2017 [Immigrants in Norway in 2017] (Statistiske analyser 155). Statistics Norway.

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2006). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73(2), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00417

- Sénéchal, M., & Young, L. (2008). The effect of family literacy interventions on children’s acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 880–907. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308320319

- Shah, B., Dwyer, C., & Modood, T. (2010). Explaining educational achievement and career aspirations among young British Pakistanis: Mobilizing ‘ethnic capital’? Sociology, 44(6), 1109–1127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510381606

- Shavers, V. L. (2007). Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of National Medical Association, 99(9), 1013–1023.

- Shute, V. J., Hansen, E. G., Underwood, J. S., & Razzou, R. (2011). A review of the relationship between parental involvement and secondary school students’ academic achievement. Education Research International, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/915326

- Sirin, S. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

- Stapleton, L. M. (2010). Incorporating sampling weights into single- and multilevel analysis. In L. Rutkowski, M. von Davier, & D. Rutkowski (Eds.), Handbook of international large-scale assessment background, technical issues, and methods of data analysis (pp. 363–388). CRC Press.

- Statistics Norway. (2017, January 18). Norwegian Standard Classification of Education. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/norwegian-standard-classification-of-education

- Statistics Norway. (2022, March 7). Immigrant and Norwegian-born immigrant parents. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/innvandrere-og-norskfodte-med-innvandrerforeldre/articles-for-immigrants-and-norwegian-born-to-immigrant-parents/immigrants-and-norwegian-born-to-immigrant-parents-at-the-beginning-of-2022

- Steinkellner, A. (2017). Hvordan går det med innvandrere og deres barn i skolen? [How are immigrants and their children doing in school?]. In T. Sandnes (Ed.), Innvandrere i Norge 2017 [Immigrants in Norway in 2017] (pp. 78–94). Statistics Norway.

- Steinkellner, A. (2020). Nesten 15 prosent er innvandrere [Nearly 15 percent are immigrants]. Statistics Norway. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/nesten-15-prosent-er-innvandrere

- Strand, O., & Schwippert, K. (2019). The impact of home languange and home resources on Reading achievement in ten-years-olds in Norway, PIRLS 2016. Nordic Journal of LIteracy Research, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v5.1260

- Strand, O., Wagner, Å. K. H., & Foldnes, N. (2017). Flerspråklige elevers leseresultater [Multilingual students’ reading scores]. In E. Gabrielsen (Ed.), Klar framgang! Leseferdighet på 4. og 5. trinn i et femtemårsperspektiv [Clear progress! Reading skill in the fourth and fifth grades from a 15-year perspective] (pp. 75–95). Universitetsforlaget.

- Suárez-Orozco, C., Rhodes, C. J., & Milburn, M. (2009). Unraveling the immigrant paradox. Youth & Society, 41(2), 151–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09333647

- Suárez-Orozco, M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2015). Children of immigration. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(4), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721715619911

- Tam, V. C., & Chan, R. M. (2009). Parental involvement in primary children’s homework in Hong Kong. School Community Journal, 19(2), 81–100.

- Tazouti, Y., & Jarlégan, A. (2014). Socioeconomic status, parenting practices and early learning at French kindergartens. International Lournal of Early Years Education, 22(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2014.949225

- Tazouti, Y., & Jarlégan, A. (2016). The mediating effects of parental self-efficacy and parental involvement on the link between family socioeconomic status and children’s academic achievement. Journal of Family Studies, 25(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1241185

- Thomson, S. (2018). Achievement at school and socioeconomic background – An educational perspective. NPJ Science of Learning, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0022-0

- TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. (2016). PIRLS 2016 International Database. Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-database/index.html

- TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. (2017). PIRLS 2016 achievement scaling methodology. In M. O. Martin, I. V. S. Mullis, & M. Hooper (Eds.), Methods and procedures in PIRLS 2016 (pp. 11.1–11.9). Timss & PIRLS International Study Center. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/publications/pirls/2016-methods/chapter-11.html

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2018). Handbook of measuring equity in education. UNESCO. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/handbook-measuring-equity-education-2018-en.pdf

- Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2010). Cultural capital: Strengths, weaknesses and two advancements. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690903539065

- Van Ewijk, R., & Sleegers, P. (2010). The effect of peer socioeconomic status on student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 5(2), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.02.001

- Von Davier, M., Gonzales, E. J., & Mislevy, R. J. (2009). What are plausible values and why are they useful. In M. Von Davier & D. Hastedt (Eds.), Ieri monograph series: Issues and methodologies in large-scale assessments (Vol. 2, pp. 9–36). ETS. http://www.ets.org/research/policy_research_reports/publications/chapter/2009/hlbj

- White, K. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.461

- Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. Educational Review, 66(3), 377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013780009