?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Higher academic performance is almost universally considered a good thing, and most quantitative studies show that performance is positively, although weakly, related to mental health. Simultaneously, however, qualitative studies consistently find that high-performing students and students attending high-performing schools report high levels of stress and other mental health problems. This study investigates a simple explanation for this puzzle – that the relationship between performance and mental health is not linear and is conditional on the performance culture of the school. Data on almost 5000 Swedish students from the Programme for International Student Assessment were used. The results show that the relationship between performance and mental health is generally not linear and that intermediate-performing boys have the best mental health, while both low- and high-performing girls and boys alike have poorer mental health. Although inconclusive, the results also suggest that low-performing students may be vulnerable to a strong school performance culture.

Introduction

Higher academic performance is almost universally considered to be a good thing. Accordingly, higher academic performance has been hailed as a panacea for a range of social ills, including social inequality, economic growth, unemployment, and, not least, stalled social mobility and a dysfunctional meritocracy (Sandel, Citation2020). As put by the main right-wing opposition party in Sweden: “Schools are the gateway to social mobility, where all children and adolescents should be given the tools to fulfil their dreams and reach their full potential” (Motion Citation19/Citation20:Citation2828, Citation2019). A recent Swedish government report even goes as far as to state that a core task of the Swedish education system is to “prepare individuals so that they themselves can manage structural inequality” (SOU, Citation2020, pp. 86–87).

In line with this optimistic view of the benefits of education, most quantitative research shows that academic performance and mental health are positively related, albeit not very strongly (e.g. Amholt et al., Citation2020), and the dominant theoretical models in educational and developmental psychology typically take this positive relationship as point of departure (e.g. Masten et al., Citation2005).

Recently, however, the performance discourse has come under fire for bringing about stress, anxiety, perfectionism, and other mental health problems among students (Curran & Hill, Citation2019; Luthar et al., Citation2013). In societies underpinned by competitive individualism and education-driven meritocracy, young people are told that everyone can “succeed” in life if they want to and that “success” requires or is even synonymous with academic success (Markovits, Citation2019; Sandel, Citation2020). The consequence is that low-performing students are marked as losers, with demoralizing effects on self-esteem and identity (Reay & Wiliam, Citation1999). However, the performance imperative is not limited to the “losers”; it also pushes the high-performing students into a constant competition for recognition and for access to a limited number of slots in high-status schools or programmes. Accordingly, qualitative studies show that adolescents report that the pressure to perform in school is among the most stressful aspects of life and that this holds true for low- and high-performing students alike (e.g. Denscombe, Citation2000; Hiltunen, Citation2017).

At the risk of oversimplification, and with the caveat that diverging epistemological paradigms inhibit direct comparisons of quantitative and qualitative research, we thus have two seemingly contradictory sets of research findings – quantitative studies showing that higher performance is generally related to better mental health, and qualitative studies reporting that high-performing students also often report mental health problems. How can this contradiction be understood? In this study, I propose and test a simple hypothesis – what if the relationship between performance and mental health is not linear or monotonic, as assumed by the vast majority of quantitative research on the topic, but that both low- and high-performing students can report mental health problems, although for partly different reasons? Specifically, the study addresses two research questions:

RQ1: Is the relationship between academic performance and mental health non-linear?

RQ2: Is the relationship between academic performance and mental health moderated by the school performance culture? This second research question is derived from qualitative studies emphasizing that academic performance is not merely an individual characteristic, but that the performance culture of the school and peers is important in itself (Stentiford et al., Citation2021).

This study makes three contributions to the literature on academic performance and mental health. First, it is among the first studies to explicitly investigate non-linear relationships between performance and mental health. While this may sound like a technical detail, it is not inconsequential. The inferences that can be drawn from a statistical model are only informative of that specific model, and if the model provides a poor approximation of the underlying reality, the inferences may not be valid. Because linearity is implicitly assumed by most existing quantitative studies, the results of these studies may not be very informative if the relationship is in fact not well described by a straight regression line. By modelling more complex relationships, this study allows for a more composite and arguably more realistic picture to emerge.

Second, by explicitly modelling non-linear relationships, and investigating how these are conditional on contextual characteristics, this study can improve our knowledge of how performance and mental health interrelate across different groups of students and types of schools. While the data in this study do not allow for causal conclusions, such knowledge can in turn inform the development of more complex theoretical models that can be tested in future studies.

Third, a more fine-grained picture of the relationship between performance and mental health can aid school practitioners in identifying students at risk of developing mental health problems. Knowledge of the potential downsides with a strong focus on performance may also be of relevance for policymakers and the general public who value outcomes beyond just performance in schools.

Background

Performance and mental health

I begin with a note on the conceptualization of the key terms of this study and the type of literature covered in the research background. Regarding performance, I cover research on grades and results on important tests (e.g. national and high-stakes tests) as well as on low-stakes academically driven tests such as those used in large-scale international assessments. I do not consider research on school failure, as this is by definition dichotomous and thus less relevant from the perspective of linear vs. non-linear associations. Empirically, performance is measured through students’ results in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). As for mental health, I discuss a broad set of measures related to wellbeing (e.g. life satisfaction), mental disorders (e.g. depression or anxiety), and self-reported internalized problems (e.g. sadness). I do not consider externalizing problems because the mechanisms linking this with performance are different. Empirically, mental health is measured through negative and positive affect (Watson et al., Citation1988).

Previous research

Numerous empirical studies have investigated the interrelationships between academic performance and mental health. For instance, literature reviews and meta-analyzes have been conducted on the relationships between performance and subjective well-being (Amholt et al., Citation2020; Bücker et al., Citation2018), depression (Huang, Citation2015), internalized problems (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2020), and mental health more broadly (Gustafsson et al., Citation2010). Although findings differ across studies, the overall conclusion from these is that higher performance is related to better mental health and that the relationship is often found to be bidirectional and small or moderate in size (Amholt et al., Citation2020; Bücker et al., Citation2018; Huang, Citation2015; Roeser et al., Citation2008).

The positive and bidirectional relationship between performance and mental health is typically explained with reference to three theoretical models (Deighton et al., Citation2018; Masten et al., Citation2005; Moilanen et al., Citation2010). First, according to the academic-incompetence model low performance can cause mental health problems. This may be due to low self-esteem or worries about the consequences of academic failure. In a more encompassing formulation, the model also implies that high performance leads to feelings of competence and to better mental health (cf. self-determination theory; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Second, according to the adjustment-erosion model, mental health problems may inhibit performance. This may be due to poor self-esteem, lack of motivation, or social withdrawal. In a more encompassing formulation, the model also implies that good mental health is related to higher self-esteem and motivation, which in turn is conducive for performance (cf. broaden-and-build theory; Fredrickson, Citation2001). Third, according to the shared-risk model the relationship between performance and mental health may be spurious and due to a third factor that causes both, such as personality characteristics or socio-economic status.

A shared but seldom explicit assumption behind all three models is that the relationship between performance and mental health is linear or at least monotonic. That is, it is assumed that academic performance and mental health always move in the same direction and that low performance is associated with worse mental health, high performance with better mental health, and intermediate performance with intermediate mental health. This assumption is also shared by the vast majority of quantitative research on the topic (Bücker et al., Citation2018). With a few notable exceptions (Modin et al., Citation2015), most studies to date have used model specifications in which a linear relationship between indicators of performance and mental health is assumed beforehand. There are, however, theoretical and empirical reasons to question this assumption.

The academic-incompetence model, stating that lower academic performance causes poorer mental health, does not consider the potential costs of performing well. However, high performance can require substantial investments in terms of hard work and emotional engagement, which can come at a cost in terms of mental health. In addition, the model does not take aspirations into account and that a relatively good performance may still be experienced as a failure by more ambitious students (Nygren, Citation2021; Pedersen & Eriksen, Citation2021). Likewise, the adjustment-erosion model, stating that mental health problems inhibit performance, does not consider the possibility that good mental health may lead to lower effort and thereby lower performance because students may then not feel that high performance is necessary for their self-worth. The shared-risk model does not consider that some of the same characteristics that drive students towards high performance, such as perfectionism or neuroticism (Curran & Hill, Citation2019; Eriksen, Citation2021; Ollfors & Andersson, Citation2021), may also predispose them to mental health problems.

These arguments are in line with empirical findings from two strands of research that have developed partly independently of the mainstream quantitative research discussed in the beginning of this section.

First, person-centred quantitative studies have identified subgroups with different mental health profiles among high- and low performing students (Roeser et al., Citation2008; Tuominen-Soini et al., Citation2008; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, Citation2014). The quantitative studies discussed so far have been variable-oriented, meaning that the focus is on how characteristics of individuals (e.g. performance and mental health) are related across individuals. Person-centred studies, in contrast, focus on how characteristics are related within individuals. Instead of asking “what is the average correlation between performance and mental health in a population?”, person-centred studies ask “what categories of students can be identified based on their combined performance and mental health characteristics?”. An important finding in person-centred studies is that high or low performance per se does not entail good or poor mental health; rather, the relationship between performance and mental health is contingent on how students relate to school. Students who are focused on the demonstration of performance, pre-occupied with the risk of failure, and motivated by external rewards often have mental health problems despite high performances, while students who are disengaged and do not value school often have good mental health despite low performances (Tuominen-Soini et al., Citation2008; Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, Citation2014). What matters for mental health may be the extent to which students’ self-worth is tied to their performances, not necessarily performance in itself (Eriksen, Citation2021).

Second, qualitative and ethnographic studies report that students’ describe the relationship between their performances and mental health as multifaceted (Denscombe, Citation2000; Hiltunen, Citation2017; Krogh, Citation2022; Låftman et al., Citation2013; Nygren, Citation2021; Reay & Wiliam, Citation1999; Stentiford et al., Citation2021). Two narratives stand out in this literature. The first is that both low- and high-performing students report mental health problems related to their experiences in school, but for partly different reasons. Low-performing students often experience stigma and shame and worry that failure in school will severely constrain their future opportunities in life (Denscombe, Citation2000; Hiltunen, Citation2017; Reay & Wiliam, Citation1999). High-performing students, in turn, often construct their sense of self around their performances and therefore view suboptimal performances as a threat to their identity. They also often come from advantaged social backgrounds and internalize the explicit or implicit expectations of their parents (Eriksen, Citation2021). Thus, they have high educational aspirations and are cognizant that top performance is required to fulfil aspirations. Suboptimal performances then become a threat to their social status and future plans in life (Allelin, Citation2019; Denscombe, Citation2000; Krogh, Citation2022; Nygren, Citation2021). The second common narrative is that the meaning of one's performance is influenced by contextual characteristics, especially the aspirations, performances, and social backgrounds of peers. Schools with many high-performing students and with an advantaged social composition can generate competitive and performance-oriented cultures in which concerns regarding social comparisons become salient (Krogh, Citation2022; Låftman et al., Citation2013; Nygren, Citation2021; Pedersen & Eriksen, Citation2021; also Luthar et al., Citation2013). In such school cultures, relatively low-performing students may experience additional stigma, while high-performing students may experience an even stronger pressure to perform in order to keep up with their peers.

Performance and mental health in a Swedish context

Several studies have documented a decline in mental health – e.g. an increase in self-reported problems and diagnosed disorders – among Swedish adolescents, especially girls, since the 1990s (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2018). In the late 1990s, the performance of Swedish students in international assessments also began to decline (Gustafsson et al., Citation2016), and the share of students who failed to become eligible to or to graduate from upper secondary school increased (SOU, Citation2019). The decline in performance and the increased rates of school failure have been cited as important reasons behind the mental health trends (Ågren & Bremberg, Citation2022; Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2018). This reasoning is supported by studies showing the importance of school-related stress and demands for mental health among Swedish adolescents, especially girls (Giota & Gustafsson, Citation2020; Högberg et al., Citation2020), and by studies showing that the decline in school-related mental health has been greatest among low-performing students (Högberg et al., Citation2021; Klapp et al., Citation2021). However, it should be noted that the trends in performance and mental health in Sweden partly diverged after 2015, when performance in international assessments began to improve (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2019) while the decline in mental health continued (Högberg et al., Citation2020). The parallel trends in performance and mental health until around 2015 are interesting and could be interpreted as indicating that the trends are related. However, the diverging trends in recent years suggest that the relationship may be more complicated.

Data and methods

Data

I use data from PISA. PISA is a cross-sectional school-based survey managed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and is carried out every 3 years in a range of high- and middle-income countries. The target population is students aged 15 years. Students with disability or insufficient language proficiency, and schools that primarily enrol students with these characteristics, can be excluded from the sampling frame. In the Swedish 2018 survey that is used in this study, a stratified sample of schools was drawn from a list of all Swedish schools with students in the relevant age range. From these schools, 7133 students were sampled with equal probability, and 5504 agreed to participate. The exclusion rate was 11.1% and the non-response rate was 13.5% (OECD, Citation2019). Around 500 students have incomplete data on the outcome variables (see below), and the final sample size is close to 5000 students, although this varies somewhat across models.

Outcome variable: negative and positive affect

Mental health is measured by positive and negative affect, which are conceptually distinct but empirically correlated dimensions (Crawford & Henry, Citation2004). High negative affect represents unpleasurable states of arousal, e.g. distress, while low negative affect represents the absence of such feelings. High positive affect represents pleasurable states of engagement, e.g. excitement, while low positive affect represents the absence of such feelings (Watson et al., Citation1988). Both negative and positive affect are correlated with depression and anxiety, but low positive affect (anhedonia) more strongly predicts depression while high negative affect more strongly predicts anxiety (Crawford & Henry, Citation2004).

The question included in PISA is, “Thinking about yourself and how you normally feel: how often do you feel as described below?” Negative affect is measured by the items “scared”, “miserable”, “afraid”, and “sad”, and positive affect by the items “happy”, “lively”, “proud”, “joyful”, and “cheerful”. Response options are “Never”, “Rarely”, “Sometimes”, and “Always”. Based on these items, I generate separate additive scales for negative (mean = 5.5; standard deviation = 2.4; range = 0–12) and positive (mean = 10.7; standard deviation = 2.7; range = 0–15) affect. Both scales show good reliability, with Cronbach's alpha equal to 0.81 (negative affect) and 0.85 (positive affect). Higher values on the negative affect scale, and lower values on the positive affect scale, indicate more mental health problems.

Independent variable: performance

In PISA, all students do not respond to all test items, and plausible values of performance are derived from the subset of items that each student responds to. If performance is the outcome variable in the analysis, the PISA Technical Report (OECD, Citation2017) states that correct standard errors are obtained by analyzing the plausible values one by one and then combining the separate estimates. However, in this study, I only use performance as an independent variable. Because the added uncertainty generated by the imputation error when the plausible values are combined is not problematic in this case (Montt & Borgonovi, Citation2018), and the average of the plausible values is not biased (Jerrim et al., Citation2017), I define performance based on the average plausible value for each student. I focus on performance in reading (mean = 505.5; standard deviation = 103.7; range = 157.1–774.6).

The first research question (RQ1) asks if the relationship between performance and mental health is non-linear. I use a second-degree polynomial to investigate non-linear relationships, meaning that each student's performance is interacted with itself (i.e. squared performance). In supplementary analyzes, I also categorize performance into deciles and use these as categorical variables. This enables an analysis of performance and mental health with less rigid functional form assumptions. The results of this analysis (presented in Figure S2) show that a second-degree polynomial captures the shape of the relationship well.

Additional covariates

The research questions are descriptive, and I do not aim to disentangle causal relations between performance and mental health. For this reason, I do not include any covariates in the models besides basic demographic characteristics, namely age (in months), gender (male = 0; female = 1), social background (measured by the PISA index of economic, social, and cultural status), and migration background (native = 0; foreign-born or at least one foreign-born parent = 1). These are fixed before performance and mental health are measured and including them will not introduce post-treatment bias but may increase the precision of the estimates.

Moderator variables

The second research question (RQ2) asks if the relationship between performance and mental health is moderated by the school performance culture. This is addressed by interacting individual performance with a set of relevant indicators of school characteristics. I here draw on the aforementioned qualitative literature emphasizing that schools characterized by high average performances and competitive climates can generate stress and other mental health problems (e.g. Krogh, Citation2022; Låftman et al., Citation2013; Nygren, Citation2021; Stentiford et al., Citation2021). First, I use a set of four items that describes the competitive motivations of students’ peers. Students are asked whether they agree to statements such as “It seems that students are competing with each other”. I combine the items into a unidimensional scale (mean = 10.4; standard deviation = 2.9; range = 4–16), with higher values indicating a more competitive climate.

Second, I average the performance in reading of all students at the school (mean = 505.5; standard deviation = 45.2; range = 367.2–658.9). A high average school performance indicates that the student attends a school with high-performing and ambitious peers in which performance comparisons are common and in which higher absolute performances are required for attaining the same relative standing. Third, I use one item from the school questionnaire directed towards the principal of the student's school: “What proportion of students in your school's final grade left school without a certificate?”. A low proportion of students without a certificate indicates that the student attends a school with high-performing peers. I reverse code the item so that higher values indicate that more students leave school with a certificate (mean = 80.0; standard deviation = 20.3; range = 0–100). Fourth, I average the social background of all students at the school (mean = 0.36, standard deviation = 0.37, range = –0.66–1.39). A high school average social background indicates that the student attends a school with an advantaged social composition. Qualitative studies have shown that performance cultures are particularly likely to emerge in such schools (Pedersen & Eriksen, Citation2021; Stentiford et al., Citation2021).

Descriptive statistics and exact measurements (survey items and response options) for all variables are presented in online supplementary file A. With the exception of the proportion of students leaving school without a certificate, all continuous independent variables have been standardized to unit variance (mean = 0; standard deviation = 1) so as to enable comparisons of effect sizes.

Analytical procedure

The data have a hierarchical structure, with students nested in schools. I therefore use linear multilevel regression models with random intercepts for schools. Specifically, I estimate two types of models.

where

represents negative or positive affect for student i in school j, i = 1, … , n, j = 1, … , m. The fixed part of the model includes the intercept

, the regression coefficients

and

, corresponding to individual performance and squared individual performance,

, the regression coefficients

,

, and

for individual-level covariates age

, social background

, and migration background

, respectively. The random part of the models includes the school-level intercept

and the individual-level error term

.

Compared to model 1, model 2 adds four fixed components: the regression coefficients , corresponding to the moderator variable

,

, corresponding to the two-way interaction term between individual performance

and the moderator variable

,

, corresponding to the three-way interaction term between squared individual performance

and the moderator variable

, and

, corresponding to individual-level covariate gender

. The coefficient

is added since model 2 is fit for both genders combined. The model is fitted separately for each moderator variable. Model 2 addresses RQ2.

All analyzes were conducted using Stata v 14 (StataCorp, Citation2015).

Results

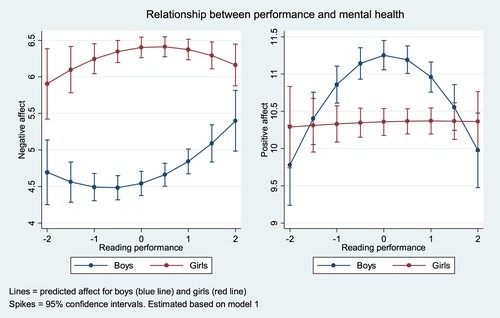

For ease of exposition, I report the results graphically throughout (regression coefficients and standard errors are reported in online supplementary file B). I begin by addressing RQ1. There is a curvilinear but on average positive relationship between performance and negative affect (left panel). Among boys, there is a small decline in negative affect from the lowest to the middle parts of the performance distribution, and then again a steep increase in the highest part of the distribution. For girls the increase is weaker and most pronounced from the lower to the middle parts of the performance distribution. The second-degree polynomial is significant for both boys (β = 0.126, p < 0.05) and girls (β = –0.092, p < 0.05). A similar but more pronounced pattern can be seen with positive affect as the outcome, namely a strongly curvilinear relationship for boys but no relationship for girls. Thus, for boys the lowest levels of positive affect are found among both low- and high-performers. The second-degree polynomial is significant for boys (β = –0.344, p < 0.001) but not for girls (β = –0.008, p = n.s.). Overall, boys with intermediate performance emerges as the group with best mental health, while all categories of girls as well as high- and (to a lesser extent) low-performing boys appear more vulnerable ().

together address RQ2. In order to avoid the additional complexity associated with reporting interactions between performance, gender, and each moderator variable, I report average relationships for girls and boys combined from now on.

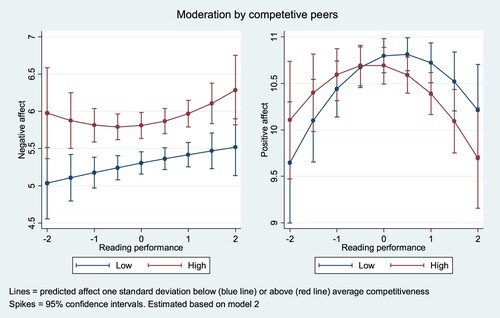

shows how the relationship between performance and mental health is moderated by the competitiveness of a student's peers. Students with more competitive peers report higher levels of negative affect (left panel), and this is true for low- as well as high-performing students. Low-performing students with competitive peers report somewhat higher levels of positive affect, while the opposite is true among high-performing students. The two-way interaction between competitiveness and performance is significant with positive affect as the outcome (β = –0.121, p < 0.05).Footnote1

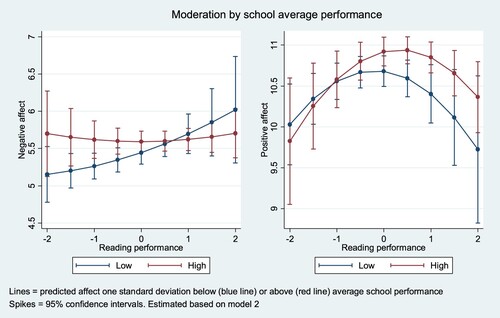

shows how the relationship between performance and mental health is moderated by the school average performance. Low-performing students attending high-performing schools report higher negative affect (left panel) but not lower positive affect (right panel). High-performing students attending high-performing schools report slightly lower negative affect and higher positive affect. The two-way interaction between school average performance and individual performance is significant with negative affect as the outcome (β = –0.108, p < 0.05).

shows how the relationship between performance and mental health is moderated by the proportion of students who leave school with a certificate. Low-performing students report more negative affect and less positive affect when attending a school with higher performing peers, while the mental health of students with intermediate or high performance is less dependent on the performance of their peers. The three-way interaction between the proportion of students with a certificate and squared performance is significant with negative affect as the outcome (β = –0.004, p < 0.05), and the two-way interaction between the proportion of students with a certificate and performance is significant with positive affect as the outcome (β = –0.008, p < 0.05).

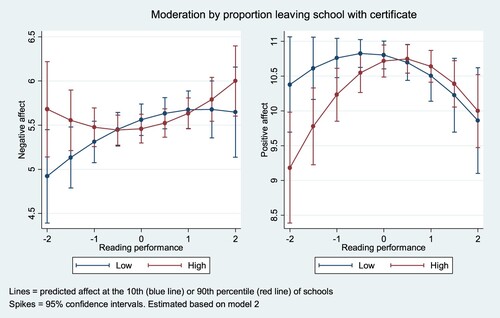

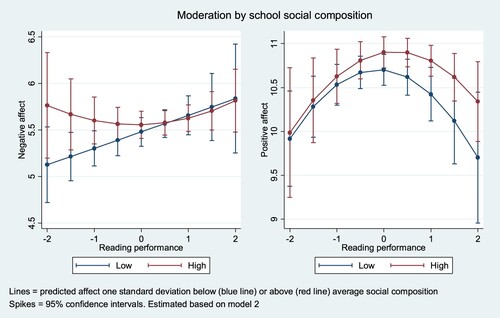

shows how the relationship between performance and mental health is moderated by the school social composition. Low-performing students report more negative affect but not less positive affect when attending a school with a more advantaged social composition. High-performing students report high positive affect but not lower negative affect when attending a school with a more advantaged social composition. The interactions between performance and school social composition are, however, non-significant for both outcomes.

Supplementary analyzes

Figure A1 and Table A2 in the online supplementary materials show that students classified as having special education needs have considerably lower reading scores, which supports the validity of using reading scores as an indicator of performance. Figure C1 shows results when performance is categorized into deciles and entered as categorical variables in the models. Because predicted affect scores are calculated for each performance decile separately, this analysis relies on substantially weaker functional form assumptions. The results indicate that the second-degree polynomial used in the main analyzes captures the shape of the relationship between performance and mental health rather well. Supplementary file D shows that the point estimates are occasionally somewhat smaller, but have the same sign, if the models are re-estimated using multiple imputation to account for missing covariate values. Supplementary file E shows that the results remain similar when the models are adjusted for student's special education needs, suggesting that the relationships in do not merely reflect relationships between special education needs and mental health. Supplementary file F shows separate estimates for low, intermediate, and high levels of negative or positive affect. There is no relationship between performance and high negative or low positive affect for girls, but a curvilinear relationship for boys. Supplementary file G shows that the second-degree polynomial for girls and with negative affect as an outcome is somewhat reduced in size and turns insignificant when removing influential observations. Supplementary file H shows results from residual analyzes. For boys and with positive affect as the outcome, there are signs of non-linearity and heteroskedasticity. Accounting for this using third- or fourth-degree polynomials and heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors does not change the overall conclusions of the study.

Discussion and conclusions

This study addressed two questions: Is the relationship between academic performance and mental health non-linear (RQ1), and is the relationship between academic performance and mental health moderated by the school performance culture (RQ2)?

With regard to RQ1, the results showed that the relationship between performance and mental health was only linear for girls and with positive affect as the outcome, but otherwise showed clear non-linear patterns. Thus, a main conclusion of this study is that both low- and high performing students can report disproportionally high levels of mental health problems, while intermediate-performing boys emerges as the group with the best mental health. Against this background, it is noteworthy that quantitative studies have found what, given the importance of school in the lives of adolescents, seems to be surprisingly weak linear relationships between performance and mental health (Bücker et al., Citation2018; Huang, Citation2015; Roeser et al., Citation2008). One interpretation of this is that these studies may have underestimated the strength of the relationship because of the implicit assumption of linearity. For instance, in this study, a linear specification would have led to the erroneous conclusion that there was no relationship between performance and positive affect for boys.

The findings in this study are more in line with what has been reported in qualitative studies (e.g. Hiltunen, Citation2017) and a handful of person-oriented quantitative studies (e.g. Tuominen-Soini & Salmela-Aro, Citation2014). However, the finding that it was mainly among boys that high performance was negatively related with mental health runs counter to most qualitative results (Stentiford et al., Citation2021). One interpretation is that most girls, irrespective of their own performance and aspirations, experience a strong performance pressure, while for boys this pressure is more confined to those with high aspirations. This would be in line with Krogh (Citation2022), who found that boys without high aspirations had more opportunities than girls to “opt out” from the performance culture and construct their status and identity based on non-academic aspects. Indeed, the poor mental health among high-performing boys may reflect the rejection of academic values that is often reported by boys, where high performers are regarded as “nerds” rather than “cool” (Krogh, Citation2022).

The conflicting findings in qualitative and mainstream quantitative research raises the question of why these strands of the literature seem to have developed along separate tracks on this issue (cf. Eriksen, Citation2021) or, more specifically, why a core finding of qualitative studies – that both low- and high-performing students report mental health problems, but for partly different reasons – has not been incorporated in the mainstream quantitative methodology. This may reflect the incentive structures of institutionalized social science that reward specialization in increasingly narrow fields rather than open-ended interdisciplinary dialogue. It may also reflect simple convenience: it is easier to fit and interpret the output from models without interactions or polynomials. From this perspective, this study can be taken as a cautionary note on the sometimes unreflective use of linear model specifications in research on performance and mental health, but also as an invitation to greater engagement with qualitative studies by quantitative researchers in the field (cf. Luthar et al., Citation2013). It should be stressed, however, that the quantitative studies discussed in this paper differ from the qualitative studies along several dimensions besides functional form assumptions, such as research objectives, epistemological paradigms, or sample sizes. While interdisciplinary comparisons are valuable, they ought to be conducted on the basis of a mutual understanding of the particularities of different traditions.

With regard to RQ2, the results were more mixed and inconclusive. Three out of four moderator variables – competitive peers, school average performance, and the proportion of students who leave school with a certificate – significantly moderated the relationship between individual performance (or squared performance) and at least one of the two outcomes. However, most interaction terms were small and non-significant. While strong conclusions in this regard are therefore not warranted, there is an indication that low-performing students may be more vulnerable to intense performance cultures in school, although the opposite was true for moderation by competitive peers. This admittedly tentative conclusion would again echo Krogh’s (Citation2022) finding that low-performing students, or students with lower aspirations, found it more difficult to “opt out” from the performance culture if attending high-performing schools, and instead were likely to be looked down upon.

The findings of this study may be understood against the background of institutional features of the Swedish education system. In this study I look at students in the final year of compulsory school. Because access to upper secondary school is regulated by student's final grades, performance during this year carries high stakes (Lundahl et al., Citation2017). For low-performing students, the stakes are even higher because failure to attain the passing grades required for eligibility has substantial negative consequences for their future educational and employment prospects (SOU, Citation2019). Thus, the overall high stakes tied to performance at this stage may to some extent explain the poor mental health among both low- and high performing students. Low-performing students may worry about failing to become eligible (Hiltunen, Citation2017), while ambitious high-performing students may feel pressure to attain the grades necessary to access their preferred upper secondary school or programme (Giota & Gustafsson, Citation2020; Nygren, Citation2021). Moreover, there are indications that Swedish schools have become less adaptive to the needs of students with mental health problems. For instance, there has been a rise in individual work and a decline in teacher-led class teaching (Allelin, Citation2019; Giota & Emanuelsson, Citation2018). If students with mental health problems find it more challenging to organize their own learning, we would expect them to be overrepresented among low-performers.

The findings of this study also shed light on the previously discussed trends in performance and mental health among Swedish adolescents. The poor mental health of low-performing students (especially boys) corroborates the interpretation that increased rates of school failure may have contributed to the declining mental health over time (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2018). The (admittedly weak) evidence that low-performing students may be more vulnerable to intense performance cultures is in line with the interpretation that the stronger performance pressures in Swedish schools in the last decade – e.g. a stronger focus on standards, stricter eligibility criteria, and earlier and more intense grading and national testing – may have disproportionally harmed low-performing students (cf. Högberg et al., Citation2021; Klapp et al., Citation2021).

Shifting from the Swedish context to a more global perspective, the findings may also be understood against the background of wider cultural shifts in Western societies, not least the rise of competitive individualism and education-driven meritocracy. In contemporary Western societies, education systems act as sorting machines (Domina et al., Citation2017) that allocate prestige and life chances based on students’ performances. In a society underpinned by education-driven meritocracy, merit is construed to be synonymous with academic success (Luthar et al., Citation2013), and the inequalities that result from the educational sorting process are deemed to be both just and natural. As a consequence, the identities of adolescents are increasingly tied to their academic performance, which, because this performance in relentlessly tested and measured, makes their self-worth increasingly sensitive to external approval (Curran & Hill, Citation2019; Eriksen, Citation2021; Sandel, Citation2020). At the lower end of the performance distribution, failing in school becomes a mark of deficient character and ability (Reay & Wiliam, Citation1999). At the upper end of the distribution, the intense competition for recognition and access to high-status schools or programmes generates status anxiety (Krogh, Citation2022; Pedersen & Eriksen, Citation2021; Stentiford et al., Citation2021).

Limitations

This study and its findings should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the data at hand do not allow for causal inferences. The results should instead be regarded as descriptive and as consistent with different causal explanations. As for the relationships between performance and mental health (RQ1), it could be that performance and performance pressures affect mental health, that mental health affects performance, and that both are affected by a third factor. Future research should combine longitudinal designs with less rigid functional form assumptions, which would allow for more credible causal explanations of the non-linear relationships found here. As for the moderating role of contextual characteristics, it is well-known that causal conclusions regarding contextual effects should be made with caution (Manski, Citation1993). Thus, the results in this study are consistent with low-performing students being more vulnerable to performance cultures, but also with low-performing students with mental health problems being more likely to attend schools with stronger performance cultures.

Other limitations concern the measurement of the key variables. As for performance, the Swedish curricula partly deviate from PISA's focus on measuring competences (Nordin & Sundberg, Citation2021), and the PISA scores used in this study have been criticized on the grounds that they, due to their low stakes, may confound low effort with low ability (Gneezy et al., Citation2019). However, a recent report found that PISA score correlated strongly (around 0.6) with final grades in Sweden (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2022). As regards mental health, PISA does not have data on psychiatric diagnoses, and the findings may not generalize to more severe forms of mental illness. It should also be noted that the results vary somewhat across the two outcomes studied here (negative and positive affect), indicating that the findings may not generalize to other measures of mental health. Another limitation of the study is that PISA only collects data on a random subset of the students at a school. This may introduce measurement error because the relatively low number of students per school (around 30 on average) means that average school characteristics are measured with some uncertainty. Random measurement error of independent variables pulls regression coefficients towards zero and thus leads to attenuation bias.

Conclusions and implications

This study has shown that the relationship between academic performance and mental health among Swedish students is not linear, but that both low- and high-performing students are at risk of mental health problems. This finding casts light on the apparent puzzle of why most quantitative studies tend to find that higher performance is related with better mental health, although only weakly so, while qualitative studies consistently find that high-performing students report high levels of mental health problems. The study also showed that the relationship between performance and mental health is partly conditional on the school performance culture, with suggestive but weak evidence that low-performing students may be particularly vulnerable to intense performance cultures.

The findings of the study have implications for research, policy, and practice. As for research, one implication is that researchers ought to be careful when using linear specifications to model what may be non-linear relationships between performance and mental health. If models are incorrectly specified, they will be a poor representation of the underlying reality, in which case the conclusions as well as the substantive implications for theory and practice may be erroneous. A related implication is that quantitative researchers in general may benefit from consulting qualitative work, as this may provide more multifaceted understandings of complex social phenomena. As for policy and school practitioners, the findings imply that a strong focus on performance in school may have downsides in terms of student mental health, and that high-performing students or students in high-performing schools may also be more generally at risk of developing mental health problems despite, or even because of, their apparent success in school. Preventive interventions may therefore be warranted.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (225.6 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. I also thank Joakim Lindgren, Umeå University, for your assistance with the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data from PISA are publicly available from the OECD website: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/ The Stata code for replication of the results from this paper are available from the author on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Moderation is tested with both two-way (performance*moderator) and three-way (performance*performance*moderator) interaction terms. With four moderator variables and two outcome variables, this results in 16 interaction terms with associated p-values. In order to make the results-section more readable, I only report the coefficients for the significant interaction terms. Complete tables with coefficients can be found in supplementary file B.

References

- Ågren, G., & Bremberg, S. (2022). Mortality trends for young adults in Sweden in the years 2000–2017. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(4), 448–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948211000836

- Allelin, M. (2019). Skola för lönsamhet: om elevers marknadsanpassade villkor och vardag. Arkiv förlag.

- Amholt, T., Dammeyer, J., Carter, R., & Niclasen, J. (2020). Psychological well-being and academic achievement among school-aged children: A systematic review. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1523–1548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09725-9

- Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, D. (2004). The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(Pt 3), 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752934

- Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psycholigical Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000138

- Deighton, J., Humphrey, N., Belsky, J., Boehnke, J., Vostanis, P., & Patalay, P. (2018). Longitudinal pathways between mental health difficulties and academic performance during middle childhood and early adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 36(1), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12218

- Denscombe, M. (2000). Social conditions for stress: Young people's experience of doing GCSEs. British Educational Research Journal, 26(3), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/713651566

- Domina, T., Penner, A., & Penner, E. (2017). Categorical inequality: Schools As sorting machines. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053354

- Eriksen, I. M. (2021). Class, parenting and academic stress in Norway: Middle-class youth on parental pressure and mental health. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(4), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1716690

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Giota, J., & Emanuelsson, I. (2018). Individualized teaching practices in the Swedish comprehensive school from 1980 to 2014 in relation to education reforms and curricula goals. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 4(3), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2018.1541397

- Giota, J., & Gustafsson, J.-E. (2020). Perceived academic demands, peer and teacher relationships, stress, anxiety and mental health: Changes from grade 6 to 9 as a function of gender and cognitive ability. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(6), 956–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1788144

- Gneezy, U., List, J. A., Livingston, J. A., Qin, X., Sadoff, S., & Xu, Y. (2019). Measuring success in education: The role of effort on the test itself. American Economic Review: Insights, 1(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20180633

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Sörlin, S., & Vlachos, J. (2016). Policyidéer för svensk skola. SNS Förlag.

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Westling, M. A., Åkerman, B. A., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., Ogden, T., & Persson, R. (2010). School, Learning and Mental Health. A systematic review. Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien.

- Hiltunen, L. (2017). “Lagom perfekt: Erfarenheter av ohälsa bland unga tjejer och killar. Arkiv förlag.

- Högberg, B., Petersen, S., Strandh, M., & Johansson, K. (2021). Determinants of declining school belonging 2000–2018: The case of Sweden. Social Indicators Research, 157(2), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02662-2

- Högberg, B., Strandh, M., & Hagquist, C. (2020). Gender and secular trends in adolescent mental health over 24 years – The role of school-related stress. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 112890.

- Huang, C. (2015). Academic achievement and subsequent depression: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9855-6

- Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L., Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D., & Shure, N. (2017). What happens when econometrics and psychometrics collide? An example using the PISA data. Economics of Education Review, 61, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.09.007

- Klapp, T., Klapp, A., & Gustafsson, J.-E. (2021). The impact of assessment system on students’ psychological, cognitive, and social well-being. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA), Annual Meeting 2021.

- Krogh, S. C. (2022). ’It’s just performance all the time’: Early adolescents’ accounts of school-related performance demands and well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.2021446

- Låftman, S. B., Almquist, Y. B., & Östberg, V. (2013). Students’ accounts of school-performance stress: A qualitative analysis of a high-achieving setting in Stockholm, Sweden. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(7), 932–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.780126

- Lundahl, C., Hultén, M., & Tveit, S. (2017). The power of teacher-assigned grades in outcome-based education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1317229

- Luthar, S., Barkin, S. H., & Crossman, E. J. (2013). ’I can, therefore I must’: Fragility in the upper-middle classes. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1529–1549. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000758

- Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. The Review of Economic Studies, 60(3), 531–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298123

- Markovits, D. (2019). The meritocracy trap: How America's foundational myth feeds inequality, dismantles the middle class, and devours the elite. Penguin Press.

- Masten, A. S., Roisman, G. I., Long, J. D., Burt, K. B., Obradović, J., Riley, J. R., Boelcke-Stennes, K., & Tellegen, A. (2005). Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 733–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733

- Modin, B., Karvonen, S., Rahkonen, O., & Östberg, V. (2015). School performance, school segregation, and stress-related symptoms: Comparing Helsinki and Stockholm. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(3), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.969738

- Moilanen, K. L., Shaw, D. S., & Maxwell, K. L. (2010). Developmental cascades: Externalizing, internalizing, and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000337

- Montt, G., & Borgonovi, F. (2018). Combining achievement and well-being in the assessment of education systems. Social Indicators Research, 138(1), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1644-y

- Motion 2019/20:2828. (2019). Social rörlighet och bättre möjligheter för socialt utsatta barn och unga.

- Nordin, A., & Sundberg, D. (2021). Transnational competence frameworks and national curriculum-making: The case of Sweden. Comparative Education, 57(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1845065

- Nygren, G. (2021). Jag vill ha bra betyg En etnologisk studie om höga skolresultat och högstadieelevers praktiker [Dissertation]. Uppsala University.

- OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 technical report. PISA, OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume I) what students know and Can Do. PISA, OECD Publishing.

- Ollfors, M., & Andersson, S. (2021). Influence of personality traits, goals, academic efficacy, and stressload on final grades in Swedish high school students. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(7), 1204–1220. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.1983644

- Pedersen, W., & Eriksen, I. M. (2021). Distribution of capital and school-related stress at elite high schools. Journal of Youth Studies, 26(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1970724

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. (2018). Varför har den psykiska ohälsan ökat bland barn och unga i Sverige? Utvecklingen under perioden 1985−2014. Folkhälsomyndigheten.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. (2020). Skolans betydelse för inåtvända psykiska problem bland skolbarn – En kartläggning av systematiska litteraturöversikter. Folkhälsomyndigheten.

- Reay, D., & Wiliam, D. (1999). ’I’ ll be a nothing’: Structure, agency and the construction of identity through assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 25(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250305

- Roeser, R. W., Galloway, M., Casey-Cannon, S., Watson, C., Keller, L., & Tan, E. (2008). Identity representations in patterns of school achievement and well-being among early adolescent girls:Variable- and person-centered approaches. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 28(1), 115–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431607308676

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Sandel, M. J. (2020). The tyranny of merit: What's become of the common good? Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- SOU. (2019). Jämlikhet i möjligheter och utfall i den svenska skolan. SOU 2019:40.

- SOU. (2020). En mer likvärdig skola – minskad skolsegregation och förbättrad resurstilldelning. SOU 2020:28.

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX.

- Stentiford, L., Koutsouris, G., & Allan, A. (2021). Girls, mental health and academic achievement: A qualitative systematic review. Educational Review, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2007052

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2019). PISA 2018. 15-åringars kunskaper i läsförståelse, matematik och naturvetenskap. Skolverket.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). PISA 2018 och betygen. Analys av sambanden mellan svenska betyg och resultat i PISA 2018. Skolverket.

- Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898

- Tuominen-Soini, H., Salmela-Aro, K., & Niemivirta, M. (2008). Achievement goal orientations and subjective well-being: A person-centred analysis. Learning and Instruction, 18(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.05.003

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063