Abstract

Objectives

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a well-recognized complication of peptic ulcers and erosions. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence rate and identify risk factors for this complication in southeastern Norway.

Materials and methods

Between March 2015 and December 2017, a prospective observational study was conducted at two Norwegian hospitals with a total catchment area of approximately 800,000 inhabitants. Information regarding patient characteristics, comorbidities, drug use, H. pylori status and 30-day mortality was recorded.

Results

A total of 543 adult patients were included. The incidence was 30/100,000 inhabitants per year. Altogether, 434 (80%) of the study patients used risk medication. Only 46 patients (8.5%) used proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for more than 2 weeks before the bleeding episode. H. pylori testing was performed in 527 (97%) patients, of whom 195 (37%) were H. pylori-positive. The main comorbidity was cardiovascular disease. Gastric and duodenal ulcers were found in 183 (34%) and 275 (51%) patients, respectively. Simultaneous ulcerations at both locations were present in 58 (10%) patients, and 27 (5%) had only erosions. Overall, the 30-day mortality rate was 7.6%.

Conclusions

The incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers and erosions was found to be lower than previously demonstrated in comparable studies, but the overall mortality rate was unchanged. The consumption of risk medication was high, and only a few patients had used prophylactic PPIs. Concurrent H. pylori infection was present in only one-third of the patients.

Clinical trial registration

Bleeding Ulcer and Erosions Study ‘BLUE Study’, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier. NCT03367897.

Introduction

Gastroduodenal ulcers and erosions complicated by bleeding lead to hospitalization, with an incidence rate of 19.4–57/100,000 per year worldwide [Citation1].

It is well documented that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), Helicobacter pylori infection (H. pylori), and a history of a previous ulcer are associated with an increased risk of developing ulcers and upper gastrointestinal bleeding [Citation1,Citation2]. Conversely, the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has a protective effect [Citation3].

An increased prescription of NSAIDs and ASA has been reported [Citation4–7]. Recently, new guidelines for cardiovascular diseases have been published, and extensive use of both antithrombotic and anticoagulant therapy is recommended [Citation8]. In previous studies, it has been documented that NSAIDs result in a fourfold increased risk of bleeding from a peptic ulceration, while ASA and the presence of H. pylori double the risk [Citation9]. With concurrent use of NSAIDs and H. pylori infection, there is an eightfold increased risk of ulcer bleeding [Citation2]. In the last decade, new antithrombotic and anticoagulant medications have been introduced to clinical practice, but the risk of ulcer bleeding related to these treatment options has yet to be determined. Although well-indicated, the concomitant prophylactic use of PPIs is disturbingly low in patients admitted to hospitals due to gastrointestinal bleeding [Citation10–12].

Eradication of H. pylori is more efficacious in reducing the risk of a recurrent bleeding ulcer than long-term maintenance antisecretory therapy [Citation13–15]. Guidelines clearly recommend investigating the presence of H. pylori infection in hospitalized patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcer disease and erosions [Citation16–18]. However, there is still low adherence to H. pylori testing in these circumstances [Citation19,Citation20].

The results from Scandinavian studies vary in regard to the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcer disease [Citation21–23]. In Norway, there are limited data on the actual use of NSAIDs, ASA and other risk medications, as well as concomitant infection with H. pylori and use of protective agents such as PPIs. Moreover, it is also largely unknown whether the risk of mortality related to peptic ulcer bleeding has changed during recent decades.

Nevertheless, bleeding from a peptic ulcer is a serious complication, and a mortality rate of up to 10% has previously been reported, despite advances in medical and endoscopic treatment [Citation1,Citation24,Citation25].

The aim of this study was primarily to determine the incidence rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers and erosions in a predefined geographical area in Norway. In addition, we assessed the demographic characteristics of these patients and their use of risk medication, infection with H. pylori, concomitant use of PPIs and the impact of comorbidity on mortality.

Materials and methods

Population and case finding

We conducted a prospective observational study at Akershus University Hospital and Østfold Hospital Trust from 1 March 2015 to 31 December 2017, with a catchment population of approximately 800,000 inhabitants. Patients admitted on suspicion of gastrointestinal bleeding and patients who developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding as an in-hospital patient were consecutively assessed for study eligibility according to the protocol.

Patients (age > 18 years) presenting with either haematemesis, melena, anaemia and/or a positive test of occult blood in the stools were included if an upper endoscopy revealed an ulcer or erosion in the stomach or duodenum as a plausible bleeding source. In-hospital patients were defined as those who had peptic ulcer bleeding after hospital admission for unrelated illness.

Patients in whom the bleeding was related to a malignant ulcer, ulcus simplex, varices, Mallory-Weiss lesions or Cameron lesions were excluded.

Patients were also excluded if the bleeding had a different origin despite findings of erosions at upper endoscopy. All endoscopies were performed in dedicated gastroenterology units by gastroenterologists or resident physicians under supervision/gastroenterology trainees.

In addition, we retrospectively identified patients based on International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) codes in the health trusts administrative system. A search in the medical hospital records was performed using the following codes: K25.0, K25.1, K25.2, K25.3, K25.4, K25.5, K25.6, K25.7, K25.9 (gastric ulcer), K26.0, K26.1, K26.2, K26.3, K26.4, K26.5, K26.6, K26.7, K26.9 (duodenal ulcer), K27.0, K27.1, K27.2, K27.3, K27.4, K27.5, K27.6, K27.7, K27.9 (gastric ulcer, unspecified location), K28.0, K28.1, K28.2, K28.3, K28.4, K28.5, K28.6, K28.7, K28.9 (gastrojejunal ulcer), and K29.0, K29.1, K29.2, K29.3, K29.4, K29.5, K29.6, K29.7, K29.8, and K29.9 (gastritis and duodenitis). The patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were contacted after discharge from the hospital to obtain written consent for study participation. These data were additionally used to calculate the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding related to ulcers and erosions.

Patients who died within 30 days of initial gastroscopy were included without written consent after approval from the Regional Ethic Committee (REK 2014/2068).

Data collection

Information regarding patient age at admission, gender, ethnicity (patient’s country at birth and his/her parents’ country at birth), history of former ulcers, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and H. pylori eradication, current smoking habits, comorbidities, drug use, indication for upper endoscopy, and endoscopic findings were collected and analysed.

Medication

Information regarding the intake of medical drugs during the last four weeks prior to hospitalization was derived from the patient's medical records and structured interviews with the patient. Additionally, information was collected from the next of kin, family doctor or pharmacy if appropriate. The drugs that were registered for analysis included NSAIDs (diclofenac, ketorolac, piroxicam, meloxicam, ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, dexketoprofen, celecoxib, parecoxib, etoricoxib, nabumetone, glucosamine), ASA, non-ASA antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel, ticagrelor), warfarin, direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (heparin, dalteparin, enoxaparin), H2 blockers (ranitidine, famotidine) and PPIs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole). Both antithrombotic and anticoagulant drugs were considered risk medications.

H. pylori

H. pylori testing included two biopsies from the antrum and two from the corpus of the stomach for culture, one from the antrum and one from the corpus for rapid urease test (RUT) (BIOHIT Helicobacter pylori UFT300) and blood test sampling for ELISA IgG anti-HP antibodies (Enzygnost anti-H. pylori II/IgG from Siemens). Positive H. pylori status was recognized as at least one positive H. pylori test.

Comorbidity

Comorbidities of interest were cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmia, chronic heart failure, myocardial infarction), renal failure (e.g., abnormal serum creatinine value prior to admission, permanent need of dialysis), diabetes (type 1 and 2) and liver cirrhosis.

Endoscopic findings

Endoscopic finding of an ulcer was defined as a fibrin-covered mucosal lesion with clear depth and diameter of at least 3 mm, and erosions were defined as a fibrin-covered mucosal lesion with a diameter less than 3 mm.

Mortality

Mortality was defined as death within 30 days after initial gastroscopy.

Database

All data were registered in an electronic case report file (eCRF) by a study nurse and KKR. TED carried out random sampling control to ensure that information was registered correctly.

Statistical analysis

The total population in the catchment area and for the study period were obtained from the Norwegian official statistics published on the internet [Citation26]. The total annual incidence rates were calculated by using the mean number of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers and erosions versus the mean population. The rate is expressed per 100,000 person-years of observation.

All analyses were performed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Norwegian Regional Ethic Committee (REK 2014/2068). All eligible patients were fully informed and gave written consent to a dedicated study nurse or doctor/physician/consultant from the gastroenterological ward.

Results

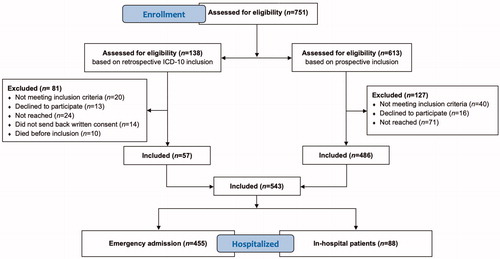

In the study period, a total of 751 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 543 (72%) were included according to the inclusion criteria. A flowchart of patient inclusion is shown in . Using the ICD-10 codes, we were able to identify 138 patients lost to prospective study inclusion, of whom 57 (41%) gave written consent to be included retrospectively. The overall incidence rate for upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers and erosions was 30/100,000 inhabitants per year.

Patient characteristics

The demographic features and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in . Interestingly, patients aged 18–45 (n = 32) seem to represent a subgroup that differs from the rest of the study population by less use of risk medication (40%), more active smokers (50%), positive H. pylori test (50%) and mainly presenting with bleeding duodenal ulcers (65%). In addition, the majority of these patients were not of Norwegian ethnicity (60%).

Table 1. Demographic, risk factors and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to emergency room or in-hospital.

Medication

In total, 434 patients (80%) used one or several risk medications (). ASA was used by 244 (45%) patients in total and by 120 (22%) patients as a single risk medication only. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, 222 (58%) had a daily intake of ASA. NSAIDs were used by 156 (28%) in total, 84 (15%) used it as a single risk medication and 55 (38%) bought NSAIDs over the counter. Out of the 88 in-hospital patients, 45 (51%) used LMWH compared to 33 (7%) of the emergency admitted patients. There were slightly more patients using DOACs than warfarin. Overall, only 46 patients (8.5%) were long-term PPI users before hospitalization.

H. pylori

H. pylori testing was performed in 527 (97%) of the patients (), of whom 195 (37%) tested positive. There was no significant difference in H. pylori positivity regarding the location of the ulcer (gastric or duodenal). Only 60 (11%) of the 527 tested patients had no history of risk medication use and were H. pylori negative.

Table 2. Ulcer location and H. pylori infection in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding (n= 543).

Comorbidity

Cardiovascular disease was the main comorbidity, present in 381 (70%) of the whole study population, and 246 (45%) patients had this comorbidity as the only comorbidity ( and ). Altogether, 411 (76%) patients had one or more comorbidities. There was no difference in the demographics and clinical presentation between patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus or renal failure or among cardiovascular disease patients with or without other comorbidities.

Mortality

Death occurred within 30 days in 41 patients (7.6%), and the mortality was higher among in-hospital patients (22.7%) compared to emergency admitted patients (4.6%) (). Eleven patients died after hospital discharge.

The mean age for patients who died was 79.3 years and equally distributed between sexes. The highest risk of mortality was for patients with liver cirrhosis, renal failure or patients with three comorbidities () was 24%, 13% and 14%, respectively.

Table 3. Distribution of comorbidities.

The main causes of death were mainly infections and cardiovascular events. In three patients, ulcer bleeding was the major cause leading to sudden death.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the incidence rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers and erosions seems to continuously decline despite a high intake of risk medication, especially in hospitalized patients, and low prehospital concomitant use of PPIs. Infection with H. pylori was found to be low after comprehensive testing. Furthermore, a higher mortality rate was present among in-hospital patients and for those with several comorbidities, but the overall mortality was comparable to previous studies.

Previous studies worldwide investigating the incidence rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers have revealed dispersed results, mainly due to geographical and demographical differences but also due to different study methodologies [Citation1,Citation27]. Hence, comparing different results may prove inaccurate and difficult. In a retrospective study from southwest Norway, the incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding was determined in two different time periods (1985–1986 and 2007–2008), at 52/100,000 and 45/100,000, respectively [Citation21]. These figures are clearly higher than ours but based on more restricted inclusion criteria. Using these criteria, our incidence would be below 25/100,000. Two Danish studies reported an unaltered incidence rate from 1993 to 2002 of 55/100,000 and 57/100,000, respectively [Citation23], and from 2005 to 2011 of 36/100,000 and 33/100,000, respectively [Citation25], while a Swedish study revealed a decreased incidence from 63.9/100,000 to 35.3/100,000 from 1987 to 2005, respectively [Citation22]. These incidence rates are more comparable to our findings.

Inclusion of in-hospital patients at a rate of 16% is consistent with other large studies, e.g., Lanas et al. [Citation19] and Hearnshaw et al. [Citation28]. Epidemiological data on the prevalence of peptic erosions are scarce, but studies have reported gastrointestinal bleeding rates up to 23% in patients with erosions [Citation11,Citation29,Citation30], which is consistent with our findings. The incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding leading to hospitalization, especially among the elderly, is believed to be driven by ASA and NSAID users rather than H. pylori infection [Citation6,Citation7,Citation23]. In our study, the majority of bleeding ulcers were attributed to or associated with ASA or NSAIDs. This is comparable to other Scandinavian studies in which they reported an association with ASA or NSAIDs in 67–74% of the cases [Citation11,Citation21,Citation25,Citation31].

We found that cardiovascular disease was the most important cause of morbidity. ASA alone or combined with non-ASA antiplatelet drugs is increasingly prescribed for either primary or secondary cardiovascular prevention. The guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology for the management of chronic coronary syndromes published in 2019 recommend the concomitant use of PPIs in patients receiving ASA monotherapy, dual antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulant monotherapy who are at high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding [Citation8]. Among our patients, 314 (58%) fulfilled these criteria, but only 32 used PPIs. This finding underlines the need for a higher awareness and better implication of the guidelines in clinical practice.

The consumption of NSAIDs was stable during the 2011–2015 period throughout Norway (47 DDD per 1000 inh/day), and for ASA, it slightly decreased (from 70 to 63 DDD per 1000 inh/day). In addition, the consumption of PPIs has increased by 26% (from 42 to 53 DDD per 1000 inh/day), and this development has been steady since 1996, when the consumption was 5 DDD per 1000 inh/day [Citation32]. Based on the present data, we are unable to determine whether a further increase in PPI consumption will have an impact on the incidence in these circumstances.

There is also a shift towards novel treatment for cardiovascular diseases, but data are still scarce concerning the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding.

A feature unique to our study is that we were able to test almost all of the patients (97%) for concomitant H. pylori infection with three different methods: culture, serology or RUT. The finding of 195 (37%) positive H. pylori patients is therefore robust. In comparison, retrospective studies performed by Kim et al. [Citation20] and Venerito et al. [Citation33] reported that only one-third of patients were tested for H. pylori infection, and 30% and 44% were positive for H. pylori, respectively.

Retrospective studies in general reveal that testing for H. pylori is not well established in daily practice and often present missing data on H. pylori status [Citation20,Citation33,Citation34].

In Norway, the presence of concomitant H. pylori infection in bleeding peptic ulcer disease is decreasing over time when compared with earlier studies [Citation11,Citation21]. Soberg et al. [Citation11] found an incidence of 51% in 2002 and 41% in 2007 in H. pylori-positive patients. Our study demonstrates that the prevalence of H. pylori in bleeding peptic ulcer disease is low and surprisingly equally present in gastric and duodenal ulcers.

Importantly, patients under 46 years of age had a high occurrence of concomitant H. pylori infection. In this patient group, only 40% were native Norwegians, so this probably reflects the immigration of people from countries with a higher incidence of H. pylori [Citation35].

Non-gastrointestinal comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus have been shown to be independent risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from peptic ulcers and could explain why the incidence remains high in the elderly population [Citation1,Citation36–38]. Liver cirrhosis contributes to markedly increased mortality [Citation37,Citation39].

In our study, nearly 80% of the patients had one or several comorbidities. Crooks et al. [Citation36] had similar results but demonstrated a lower consumption of risk medication (ASA/NSAIDs 52% vs. 72%) and a higher use of PPIs compared to our population (28% vs. 8%). This latter result is important and might indicate that there is potential to lower the incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding by increasing PPI prescriptions, especially in high-risk patients.

Studies performed in the time period 1985–2011 have shown stable mortality rates associated with bleeding peptic ulcers: approximately 11% in Denmark [Citation23,Citation25] and 5.5% in Sweden [Citation22]. To our knowledge, only one Norwegian study has previously determined the mortality rate for bleeding peptic ulcers. In the period from 1985 to 1990, Qvist et al. [Citation40] reported a total 30-day mortality of 6.3%, which is comparable to our finding. Despite both medical and endoscopic developments in treatment, the increasing average age of the patients and the burden of comorbidities may suspend this advantage. Comparing the study performed by Qvist et al. [Citation40] with our study, the mean age was 67 years vs. 72 years, respectively, and the distribution of the number of comorbidities among patients was equal, although we found an 11% higher mortality for patients with three comorbidities. However, the interpretation of mortality in relation to comorbidity has to take into account the severity and the influence of other comorbidities that were not included in our study, such as malignancy.

In-hospital patients had a higher mortality rate of 23% compared to 4.6% for patients admitted to the emergency room with a primary suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The differences between the two patient groups were also a higher proportion of comorbidity, older age, and a more severe underlying disease in the in-hospital patient group. In regard to liver cirrhosis, one of four patients died mainly due to encephalopathy and organ failure. This finding is supported by other studies [Citation37,Citation39]. Only three out of 41 deaths were solely due to bleeding from an ulcer, while infections and cardiovascular events were the main causes of death. By improving management of underlying comorbidity and acute illness, mortality, which is largely due to non-haemorrhagic causes, could be reduced further.

The major strength of our study is the prospective observational study design with a well-defined background population. We achieved a larger sample size (increased by 162 patients) by not only including patients with presenting symptoms such as haematemesis and melena but also with anaemia and positive hemoFEC signs of gastrointestinal bleeding. Additionally, we included in-hospital patients and patients with bleeding peptic erosions. Although the study was prospective, we performed additional inclusion based on ICD10 codes retrospectively. This was to catch the patients missed to active inclusion and to make sure that the data were as reliable as possible in regard to true incidence rate and mortality. Most studies use database reviews or retrospective cohort designs based on ICD10 codes to execute epidemiological studies [Citation19,Citation22–25]. This might increase the risk of misclassification of diagnosis for peptic ulcer bleeding and missing data. This can be a weakness in our study as well, but the proportion of patients included in this way is low. Another major strength is the performance of robust H. pylori diagnostics by systematic testing with three different well-established methods.

In summary, our study provides new knowledge regarding upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcers and erosions. The incidence of this complication seems to decline, although the usage of risk medication is increasing. However, mortality related to the bleeding event is essentially unchanged and influenced by comorbidities, mostly cardiovascular disease. H. pylori infection is not as important as expected since the infection was detected in only one-third of the patients and was equally distributed between gastric and duodenal ulcers. The adherence to guidelines recommending the use of PPIs is poor and therefore creates an opportunity for improvement.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants in the BLUE study group who assisted with the data collection and to Professor Truls Micheal Leegaard M.D., Astri Lervik Larsen M.D. and Heidi Johanne Espvik M.D. at the Department of Microbiology, Akershus University Hospital for analysing the H. pylori tests.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, et al. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84(2):102–113.

- Sostres C, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Benito R, et al. Peptic ulcer bleeding risk. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in NSAID/low-dose aspirin users. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):684–689.

- Scally B, Emberson JR, Spata E, et al. Effects of gastroprotectant drugs for the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcer disease and its complications: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(4):231–241.

- Sung JJ, Kuipers EJ, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(9):938–946.

- Malmi H, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ, et al. Incidence and complications of peptic ulcer disease requiring hospitalisation have markedly decreased in Finland. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(5):496–506.

- Higham J, Kang JY, Majeed A. Recent trends in admissions and mortality due to peptic ulcer in England: increasing frequency of haemorrhage among older subjects. Gut. 2002;50(4):460–464.

- Perez-Aisa MA, Del Pino D, Siles M, et al. Clinical trends in ulcer diagnosis in a population with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(1):65–72.

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):407–477.

- Sarri GL, Grigg SE, Yeomans ND. Helicobacter pylori and low-dose aspirin ulcer risk: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34(3):517–525.

- Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Arroyo MT, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinations. Gut. 2006;55(12):1731–1738.

- Soberg T, Hofstad B, Sandvik L, et al. Risk factors for peptic ulcer bleeding. Tidsskriftet. 2010;130(11):1135–1139.

- Zeitoun JD, Rosa-Hezode I, Chryssostalis A, et al. Epidemiology and adherence to guidelines on the management of bleeding peptic ulcer: a prospective multicenter observational study in 1140 patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(3):227–234.

- Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Cosme A, et al. Long-term follow-up of 1,000 patients cured of Helicobacter pylori infection following an episode of peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(8):1197–1204.

- Gisbert JP, Abraira V. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):848–863.

- Sverden E, Brusselaers N, Wahlin K, et al. Time latencies of Helicobacter pylori eradication after peptic ulcer and risk of recurrent ulcer, ulcer adverse events, and gastric cancer: a population-based cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(2):242–250e1.

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66(1):6–30.

- Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(10):a1–a46.

- Barkun AN, Almadi M, Kuipers EJ, et al. Management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: guideline recommendations from the International Consensus Group. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(11):805–822.

- Lanas A, Aabakken L, Fonseca J, et al. Clinical predictors of poor outcomes among patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1225–1233.

- Kim JJ, Lee JS, Olafsson S, et al. Low adherence to Helicobacter pylori testing in hospitalized patients with bleeding peptic ulcer disease. Helicobacter. 2014;19(2):98–104.

- Bakkevold KE. Time trends in incidence of peptic ulcer bleeding and associated risk factors in Norway 1985–2008. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:71–77.

- Ahsberg K, Ye W, Lu Y, et al. Hospitalisation of and mortality from bleeding peptic ulcer in Sweden: a nationwide time-trend analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(5):578–584.

- Lassen A, Hallas J, De Muckadell OBS. Complicated and uncomplicated peptic ulcers in a Danish county 1993–2002: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(5):945–953.

- Jairath V, Martel M, Logan RF, et al. Why do mortality rates for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding differ around the world? A systematic review of cohort studies. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(8):537–543.

- Rosenstock SJ, Moller MH, Larsson H, et al. Improving quality of care in peptic ulcer bleeding: nationwide cohort study of 13,498 consecutive patients in the Danish Clinical Register of Emergency Surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1449–1457.

- Statistics Norway; 2019 [cited 2019 Nov]. Available from: http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning

- Lin KJ, García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S. Systematic review of peptic ulcer disease incidence rates: do studies without validation provide reliable estimates? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):718–728.

- Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60(10):1327–1335.

- Enestvedt BK, Gralnek IM, Mattek N, et al. An evaluation of endoscopic indications and findings related to nonvariceal upper-GI hemorrhage in a large multicenter consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):422–429.

- Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, et al. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27(2):80–93.

- Ahsberg K, Hoglund P, Kim WH, et al. Impact of aspirin, NSAIDs, warfarin, corticosteroids and SSRIs on the site and outcome of non-variceal upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(12):1404–1415.

- Norwegian Institute of Public Health's. Drug consumption in Norway 2011–2015 (Legemiddelforbruket i Norge 2011–2015); [cited 2019 Nov]. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/en/publ/2016/legemiddelforbruket-i-norge-2011-2015-drug-consumption-in-norway-2011-2015/

- Venerito M, Schneider C, Costanzo R, et al. Contribution of Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding in patients on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, corticosteroids and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(11):1464–1471.

- Hung KW, Knotts RM, Faye AS, et al. Factors associated with adherence to Helicobacter pylori testing during hospitalization for bleeding peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(5):1091–1098.e1.

- Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–429.

- Crooks CJ, West J, Card TR. Comorbidities affect risk of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1384–1393.

- Leontiadis GI, Molloy-Bland M, Moayyedi P, et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):331–345.

- Quan S, Frolkis A, Milne K, et al. Upper-gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to peptic ulcer disease: incidence and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17568–17577.

- Holland-Bill L, Christiansen CF, Gammelager H, et al. Chronic liver disease and 90-day mortality in 21,359 patients following peptic ulcer bleeding-a Nationwide Cohort Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(6):564–572.

- Qvist P, Arnesen KE, Jacobsen CD, et al. Endoscopic treatment and restrictive surgical policy in the management of peptic ulcer bleeding. Five years' experience in a central hospital. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(6):569–576.