ABSTRACT

Social-emotional interventions (SEL) are purported to be beneficial toward all students, yet researchers call into question their effectiveness toward Black boys because of the limited SEL interventions that have been culturally adapted for them to account for their lived experiences (e.g. experiencing disparate discipline within schools). Within this review, we discuss the state of research on Black boys, provide an overview of SEL interventions, and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the current SEL intervention research base. Next, we emphasize the need for culturally relevant SEL interventions and how practitioners can make SEL interventions culturally relevant for Black boys using a universal Afrocentric framework. Finally, this article highlights recommendations for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers to improve the cultural adaptation of SEL interventions for Black boys to promote improved school outcomes.

Exclusionary discipline practices throughout PreK to high school is a consistent issue that impacts the educational success of Black boys. These methods are contentious, as research consistently demonstrates that severe disciplinary sanctions negatively impact students’ educational attainment. For instance, according to data from the US Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection, Black boys are suspended and expelled at 3 times their enrollment (US Department of Education, Citation2022). Black boys represented 7.7% of enrolled students but comprised 20.1% of in-school suspensions, 24.9% of out-of-school suspensions, and 25.9% of expulsions. Black boys are subjected to disproportionate discipline, although they do not demonstrate behavior different from their peers (Huang, Citation2018).

Even when Black boys and their peers demonstrate similar behavioral infractions, their discipline outcomes differ. For instance, Shi and Zhu (Citation2022) investigated racial disparities in exclusionary consequences for students of different races involved in the same disciplinary incident. Their results indicated that Black students faced higher suspension probabilities and longer suspensions than their White and Hispanic peers. This is also supported by research by Graves and Wang (Citation2022) which evaluated the relationships between body mass index (BMI), school affiliation, and suspension. According to their findings, BMI was not a significant predictor of school suspension for Black males, but it was for the entire group. This showed that Black boys were subjected to stricter punishment regardless of size. Cumulatively, these issues eventually lead to the school-to-prison pipeline (Owens, Citation2017). As a result, 1 method that can decrease disciplinary discrepancies is culturally relevant social-emotional interventions for Black boys.

Overview of social-emotional learning (SEL)

Social-emotional learning (SEL) entails students’ ability to comprehend, express, and control emotional aspects of their lives in ways that contribute to positive developmental outcomes in academic and social domains (Garner et al., Citation2014). SEL interventions aim to increase prosocial behaviors and reduce antisocial behaviors by teaching children global and specific social-emotional competencies throughout PreK-12 education (Garner et al., Citation2014). School-based SEL programming aid in developing critical cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies that are important in school success and life, including self-awareness (i.e., recognizing emotions, strengths, limitations, and values), self-management (i.e., regulating emotions and behaviors), social awareness (i.e., taking the perspective of and empathizing with others from diverse cultures), relationship skills (i.e., establishing and maintaining healthy relationships) and responsible decision making (i.e., making constructive choices across different situations (CASEL, Citation2023; Taylor et al., Citation2017).

Benefits of SEL programs

Numerous research studies have shown that SEL programs improve academic, emotional, and psychological outcomes for students from pre-kindergarten through high school, contribute to improving school safety, and promote healthy decision-making (e.g., Durlak et al., Citation2011, Citation2022; Mahoney et al., Citation2018; Murano et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, it has been shown that these benefits are consistently demonstrated over time. For example, Taylor et al. (Citation2017) reviewed 82 SEL interventions utilizing a positive youth development (PYD) framework from 1981–2014. The authors found that students who participated in school based SEL interventions showed consistent and significant improvements in prosocial behaviors (i.e., SEL skills, attitudes, positive social behavior, academic performance) and a reduction in maladaptive behaviors (i.e., conduct problems, emotional distress, drug use) nearly 4 years post-intervention. Further, they found these effects were significant for students from all demographic groups (14% of students of color). However, despite results suggesting the effectiveness of SEL interventions for all youth, a considerable limitation of Taylor et al. (Citation2017) and related research are that the intervention effects are not disaggregated by race/ethnicity (Roberts et al., Citation2020). For that reason, researchers have brought forth concerns about whether SEL programming adequately represents and is relevant for culturally diverse youth, such as Black boys (e.g., Jagers et al., Citation2019).

Challenges of SEL: Lack of culturally adapted interventions

While research has highlighted that SEL interventions result in improvements in the psycho-educational outcomes of diverse youth and improve educational equity by shrinking the opportunity gap, the limited research base on culturally responsive interventions often means that diverse youth, such as Black boys, may be left out of receiving SEL programming that is tailored to meet their needs (CASEL, Citation2023; Jagers et al., Citation2019).

Consequently, SEL interventions have been criticized for reflecting a White, middle-class belief system (McCall et al., Citation2022). Because of the various issues within the existing research base, researchers have questioned the utility of existent SEL programming for Black boys (e.g., Garner et al., Citation2014; Graves et al., Citation2017; McCallops et al., Citation2019), as existing research does not often disaggregate results of existing SEL interventions by race and ethnicity (Roberts et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the limited research on culturally adapted SEL interventions, particularly for Black boys, leaves educators ill-equipped to effectively meet Black boys’ needs. As a result, to better support Black boys in schools as well as to close the opportunity gap impeding Black boys, educators will need to consider strategies to make existing SEL interventions more culturally responsive to the needs of Black boys and ensure their success within schools (McCall et al., Citation2022).

Culturally adapted SEL interventions

Despite a lack of culturally relevant interventions within the research base and in practice, research has demonstrated numerous positive effects of culturally responsive interventions (Hall et al., Citation2016). Culturally adapting SEL interventions involves utilizing information about a particular cultural group (i.e., race, disability, sexual orientation, gender, religion, social class, and age) to inform, develop, and revise evidence based SEL interventions to be more effective with that group (Bernal et al., Citation1995). Hall et al. (Citation2016) conducted a meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of interventions modified to be culturally relevant for ethnically/racially minoritized students. They found in the 78 studies reviewed that such interventions reduced symptoms of psychopathology at a greater rate than control or other interventions. It is important to note that an effect size of g = 0.67 was found within their study, indicating that using culturally relevant interventions strongly impacted the reduction of the targeted symptoms. Multiple reasons may indicate why such interventions are more effective for minoritized students. One reason is that these interventions are designed to match the characteristics of the students they are intended for. When this occurs, students are more likely to be engaged and persist in participating in the intervention and are more likely to experience positive results (Soto et al., Citation2018).

Many culturally relevant interventions include similar components, such as racial identity development as well as the use of cultural values and protective factors (Aston et al., Citation2018; Graves & Aston, Citation2018; Graves et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2018; Lewis et al., Citation2006). Cultural values and protective factors are known to have a positive relationship with academic self-efficacy beliefs and positive developmental outcomes (Grills et al., Citation2016). Affirmation of Black racial identity has also been associated with lower levels of various antisocial behaviors (Rivas‐Drake et al., Citation2014). For example, Graves et al. (Citation2017) implemented a culturally adapted version of the Strong Start intervention program with a sample of 61 Black male students. Adaptations of the interventions included replacing books recommended within the traditional curriculum with books including Black characters and discussing issues relevant to the Black community. The Black males who participated made statistically significant gains in their self-regulation and self-competency skills, demonstrating the effectiveness of cultural adaptations to evidence based SEL interventions for Black youth. Additionally, the Brothers of Ujima program, which focuses on the 7 Afrocentric principles of Nguzo Saba, was implemented with 14 6th- and 7th-grade students (Nguzo Saba will be described in greater detail below; Graves & Aston, Citation2018). Results demonstrated that the students showed an increase in their endorsement of Afrocentric principles. Endorsing such values and principles can potentially decrease symptoms of stress and depression for Black adults (Neblett et al., Citation2010). Therefore, equipping students with an Afrocentric worldview to strengthen their racial/ethnic identity is essential to promoting positive outcomes for Black youth.

Universal Afrocentric (SEL) interventions

Afrocentric, aka “Afrocentrism” or “African-centered,” refers to a framework for culturally responsive positive youth development that focuses on instilling indigenous African and African diasporan cultural beliefs, values, ideologies, and practices among Black youth (Asante, Citation1991; Lateef et al., Citation2022). Interventions centered on a group’s cultural beliefs promote a sense of belonging and are more effective for that cultural group (Lateef et al., Citation2022). As a result, mounting evidence demonstrates that culturally responsive SEL interventions effectively promote positive outcomes for Black students (Jones et al., Citation2018; Kurtz et al., Citation2021; Robinson-Ervin et al., Citation2016). With the lack of culturally responsive SEL interventions and programming to meet the needs of Black students (Graves et al., Citation2021), integrating Afrocentrism through the schooling process, such as SEL interventions and programs, is 1 effective cultural adaptation to promote positive Black youth development and close the opportunity gap (Belgrave & Brevard, Citation2014; Loyd & Williams, Citation2017).

African-centered interventions (ACIs) are designed to assist Black youth in increasing their racial/ethnic pride, sense of self-belonging & worth, well-being, and appreciation of African and people of the African diaspora resistance & resilience to oppression (Belgrave & Brevard, Citation2014; Lateef & Anthony, Citation2020). Additionally, ACIs aim to improve youths’ sense of community through bonding and group engagement activities that support working together, experiencing together, and acquiring new skill sets as a collective (Belgrave & Brevard, Citation2014; Denbo & Beaulieu, Citation2002). Afrocentric interventions have demonstrated a positive association with various outcomes for Black children, including positive self-esteem, academic success, life satisfaction, anti-drug use, mental health, racial identity, and positive behaviors (Graves & Aston, Citation2018; Heidelburg & Collins, Citation2022; Jones & Lee, Citation2020; Loyd & Williams, Citation2017). Lateef et al. (Citation2022) conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of ACIs with Black youth. Researchers found that ACIs were associated with positive outcomes in Black youths’ academic achievement, racial/ethnic identity, self-concept, and behaviors.

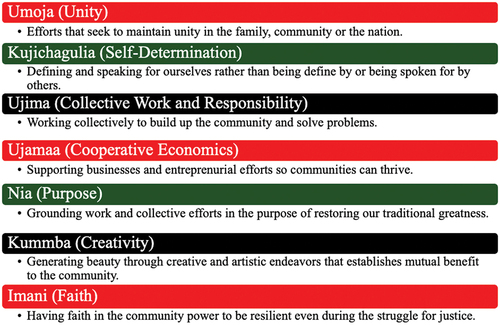

In addition, several members of the Black community have increasingly advocated for the use of Afrocentric-based policies and practices, particularly the use of culturally responsive programs for youth (Heidelburg & Collins, Citation2022; Lateef et al., Citation2022). For Black youth, utilizing the value system of Nguzo Saba as a theoretical framework for SEL interventions is 1 common approach for culturally adapting interventions to be African-centered. Maulana Karenga, 1 of the most prominent African American scholars, suggested that the 7 principles of Nguzo Saba (Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination), Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics), Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity), and Imani (Faith) are “minimum set of values’’ needed to promote positive outcomes within Black families, communities, and individuals (Karenga, Citation1988, p. 43). As a result, centering the principles of Nguzo Saba as a cultural adaptation for SEL interventions can be an effective means for assisting Black youth in navigating oppressive systems and anti-Black policies and practices as well as increase a host of positive protective factors for Black youth (Asante, Citation1991; Lateef & Anthony, Citation2020). In and , the 7 principles of Nguzo Saba are further described. gives a basic description of the 7 principles, while describes how the principles could be incorporated in SEL interventions, to assist practitioners in engaging in culturally responsive practice, based on previous research (e.g., Graves & Aston, Citation2018; Heidelburg et al., Citation2022).

Figure 1. Nguzo Saba principles & descriptions.

Table 1. Seven principles of Nguzo Saba and possible SEL intervention components

Embedding Afrocentrism into SEL interventions are critical to support the positive development of Black youth and to minimize the opportunity gap in achievement between Black students and their peers. Black youth in America are consistently exposed to negative messages, imagery, and oppressive, discriminatory experiences based on race and anti-Blackness (Heidelburg et al., Citation2022). These negative race-based experiences can impair Black youth’s perception of their Black identity. Therefore, ACIs are essential for providing Black youth with positive race-based experiences to promote healthy Black identity development (Lateef et al., Citation2022). When Black individuals view themselves as centered in Afrocentric structures, values, and practices, their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions are liberated from Eurocentrism (Asante, Citation1991; Lateef et al., Citation2022). Hence, reintroducing Black and African culture to Black youth using strengths-based African-centered SEL interventions is vital to helping youth avoid the internalization of oppressive Eurocentric ideologies and perspectives about themselves and move toward strengthening the positive racial/ethnic identity of Black youth (Loyd & Williams, Citation2017).

Thus, given the opportunities to decrease opportunity gaps, embedding culturally responsive practices in SEL interventions for Black boys is paramount. Therefore, various school stakeholders (e.g., educators, policymakers, and researchers) need to further explore how to improve the state of cultural responsiveness within SEL interventions. Each stakeholder plays a key role in helping implement culturally responsive practice and improving outcomes in Black boys. Afrocentrism holds great promise in improving outcomes for Black boys by combating negative messages and stereotypes and affirming their identity. However, it is important to continue studying the use of culturally responsive practices with other student populations that are routinely marginalized within schooling environments (e.g., Black girls). As such, future work should continue exploring how to use culturally responsive SEL practices to improve outcomes for Black girls and other marginalized student populations in schools. Furthermore, future research should explore the replicability of study findings to determine if SEL intervention effectiveness is long-standing for Black boys.

This article concludes by providing recommendations for educators, policymakers, and researchers to increase the prevalence of culturally responsive SEL interventions for Black boys. Following the references, additional resources are listed for classroom use to assist practitioners in implementing culturally responsive SEL interventions for Black boys.

Recommendations for educators, policymakers and researchers

Recommendations for educators

To increase the competency of interventionists and practitioners’ ability to adapt an SEL program to address the unique socio-cultural needs of Black boys, they should engage in perspective-taking so they can learn more about their cultures and how to engage in perspective taking so they can work effectively with Black boys (Garner et al., Citation2014).

Training should be provided to practitioners to increase their awareness of culturally responsive pedagogies and practices for Black boys. Furthermore, training should incorporate strategies to build strong relationships with Black boys and families and incorporate Black boys’ perspectives within SEL intervention implementation (McCallops et al., Citation2019).

To promote positive school outcomes for Black boys, school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports (SWPBIS) must be culturally responsive (Heidelburg et al., Citation2021). This can be done by enhancing cultural knowledge, increasing cultural self-awareness, engaging in practices to validate other cultures, engaging students in culturally relevant discussions about disciplinary sanctions, and establishing cultural validity by understanding students’ circumstances and how these contribute toward misbehavior and school staff can implement a plan to resolve behavioral issues with dignity and empathy (Parsons, Citation2017).

Cultural adaptations to evidence based SEL programming, such as Strong Start (Graves et al., Citation2017), should be utilized with Black boys to promote positive outcomes and school success (Graves & Aston, Citation2018).

Recommendations for educational policymakers and researchers

Policymakers and researchers should work to increase the prevalence of culturally specific evidence-based research on Black boys, as this work is limited (McCallops et al., Citation2019). Within SEL and behavioral intervention research, Graves et al. (Citation2021)’s systematic review of What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) found that many interventions were not culturally modified for Black children. Further, many WWC studies used to establish the evidence of behavioral interventions did not disaggregate results by race and did not look at reasons for disparate behavioral outcomes in schools. As such, the evidence base of many behavioral interventions may not apply to Black boys (Graves et al., Citation2021). Thus, researchers should position their research to understand these differences and disaggregate study results by race so study findings can be more applicable to Black boys.

Given the disparities in evidence-based interventions for Black males, policymakers and researchers should take action to increase the prevalence of school-based culturally specific SEL and behavioral intervention research on Black males to understand their unique sociocultural needs and protective factors that can improve their school outcomes. Given the importance of this topic, journals should devote more attention to special issues to increase the prevalence of culturally specific SEL research done with Black boys. Previous research has outlined that general SEL strategies alone (e.g., Schoolwide Positive behavioral interventions and supports) are insufficient to prevent disproportionate school outcomes in Black boys (Graves et al., Citation2017).

Policymakers should work to increase the prevalence of SEL and behavioral intervention research providing more data measuring treatment fidelity and social validity, as these variables are infrequently reported in existing SEL intervention studies (McCallops et al., Citation2019). As such, researchers conducting work in this area should gather these metrics, as this data can help provide feedback to improve interventions and make them more culturally responsive for Black boys (Graves et al., Citation2017).

Additional resources

1. Hayashi, A., Liew, J., Aguilar, S. D., Nyanamba, J. M., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Embodied and social-emotional learning (SEL) in early childhood: Situating culturally relevant SEL in Asian, African, and North American contexts. Early Education and Development, 33(5), 746–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.2024062

The article outlines how universally social-emotional competencies are inherently situated in students’ authentic learned experiences and presents research from 3 cultural contexts (i.e., North America, Japan, and South Africa). The article concludes with strategies educators can use to develop culturally adapted SEL interventions for Black boys.

2. Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Borowski, T. (2018). Equity &social and emotional learning: A cultural analysis. CASEL. https://measuringsel.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Frameworks-Equity.pdf

This cultural analysis outlines concerns with the CASEL competencies and includes recommendations for incorporating equity into the implementation of SEL interventions for Black boys.

3. CASEL Program Guide [website]: https://pg.casel.org/review-programs/

This program guide is a resource to help educators determine and choose SEL programming that can be culturally adapted and promotes improved school outcomes in Black boys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Asante, M. K. (1991). The Afrocentric idea in education. The Journal of Negro Education, 60(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/2295608

- Aston, C., Graves, S. L., Jr., McGoey, K., Lovelace, T., & Townsend, T. (2018). Promoting sisterhood: The impact of a culturally focused program to address verbally aggressive behaviors in Black girls. Psychology in the Schools, 55(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22089

- Belgrave, F. Z., & Brevard, J. K. (2014). African American boys: Identity, culture, and development. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1717-4

- Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., & Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01447045

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL]. (2023). Fundamentals of SEL. https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/

- Denbo, S., & Beaulieu, L. M. (2002). Improving schools for African American students: A reader for educational leaders. Thomas.

- Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., & Boyle, A. E. (2022). What we know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000383

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Garner, P. W., Mahatmya, D., Brown, E. L., & Vesely, C. K. (2014). Promoting desirable outcomes among culturally and ethnically diverse children in social emotional learning programs: A multilevel heuristic model. Educational Psychology Review, 26(1), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9253-7

- Graves, S., Phillips, S., Jones, M., & Johnson, K. (2021). A systematic review of the what works clearinghouse’s behavioral intervention evidence: Does it relate to Black children. Psychology in the Schools, 58(6), 1026–1040. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22485

- Graves, S. L., & Aston, C. (2018). A mixed‐methods study of a social emotional curriculum for Black male success: A school‐based pilot study of the Brothers of Ujima. Psychology in the Schools, 55(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22088

- Graves, S. L., Herndon-Sobalvarro, A., Nichols, K., Aston, C., Ryan, A., Blefari, A., Schutte, K., Schachner, A., Victoria, L., & Prier, D. (2017). Examining the effectiveness of a culturally adapted social-emotional intervention for African American males in an urban setting. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000145

- Graves, S. L., & Wang, Y. (2022). It’s not that they are big, it’s just that they are Black: The impact of body mass index, school belonging, and self esteem on Black boys’ school suspension. School Psychology Review, 52(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2072693

- Grills, C., Cooke, D., Douglas, J., Subica, A., Villanueva, S., & Hudson, B. (2016). Culture, racial socialization, and positive African American youth development. Journal of Black Psychology, 42(4), 343–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798415578004

- Hall, G. C. N., Ibaraki, A. Y., Huang, E. R., Marti, C. N., & Stice, E. (2016). A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 993–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.005

- Heidelburg, K., & Collins, T. A. (2022). Development of Black to success: A culturally enriched social skills program for Black adolescent males. School Psychology Review, 52(3), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2001691

- Heidelburg, K., Phelps, C., & Collins, T. A. (2022). Reconceptualizing school safety for Black students. School Psychology International, 43(6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343221074708

- Heidelburg, K., Rutherford, L., & Parks, T. W. (2021). A preliminary analysis assessing SWPBIS implementation fidelity in relation to disciplinary outcomes of Black students in urban schools. The Urban Review, 54(1), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-021-00609-y

- Hocker, K. (2021, December 21). The Nguzo Saba: Guiding principles for Kwanzaa and beyond. University of Rochester School of Nursing News and Events. https://son.rochester.edu/newsroom/2021/nguzo-saba-principles-for-kwanzaa.html

- Huang, F. L. (2018). Do Black students misbehave more? Investigating the differential involvement hypothesis and out-of-school suspensions. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(3), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1253538

- Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): Toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

- Jones, J. M., & Lee, L. H. (2020). Cultural identity matters: Engaging African American girls in middle school. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 45(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2020.1716285

- Jones, J. M., Lee, L. H., Matlack, A., & Zigarelli, J. (2018). Using sisterhood networks to cultivate ethnic identity and enhance school engagement. Psychology in the Schools, 55(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22087

- Karenga, M. (1988). The African American holiday of Kwanzaa: A celebration of family, community & culture. University of Sankore Press.

- Kurtz, K. D., Pearrow, M., Battal, J. S., Collier-Meek, M. A., Cohen, J. A., & Walker, W. (2021). Adapting social emotional learning curricula for an urban context via focus groups: Process and outcomes. School Psychology Review, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2021782

- Lateef, H., Amoako, E. O., Nartey, P., Tan, J., & Joe, S. (2022). Black youth and African-centered interventions: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 32(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315211003322

- Lateef, H., & Anthony, E. K. (2020). Frameworks for African-centered youth development: A critical comparison of the Nguzo Saba and the five cs. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 29(4), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1449690

- Lewis, K. M., Sullivan, C. M., & Bybee, D. (2006). An experimental evaluation of a school-based emancipatory intervention to promote African American well-being and youth leadership. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798405283229

- Loyd, A. B., & Williams, B. V. (2017). The potential for youth programs to promote African American youth’s development of ethnic and racial identity. Child Development Perspectives, 11(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12204

- Mahoney, J. L., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2018). An update on social and emotional learning outcome research. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(4), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718815668

- McCall, C. S., Romero, M. E., Yang, W., & Weigand, T. (2022). A call for equity-focused social-emotional learning. School Psychology Review, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2093125

- McCallops, K., Barnes, T. N., Berte, I., Fenniman, J., Jones, I., Navon, R., & Nelson, M. (2019). Incorporating culturally responsive pedagogy within social-emotional learning interventions in urban schools: An international systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 94, 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.007

- Murano, D., Sawyer, J. E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2020). A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 227–263. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465432091474

- Neblett, E. W., Jr., Hammond, W. P., Seaton, E. K., & Townsend, T. G. (2010). Underlying mechanisms in the relationship between Africentric worldview and depressive symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017710

- Official Kwanzaa Website. (2020). The symbols of Kwanzaa. https://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/the-symbols.html

- Owens, E. G. (2017). Testing the school‐to‐prison pipeline. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 36(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21954

- Parsons, F. (2017). An intervention for the intervention: Integrating positive behavioral interventions and supports with culturally responsive practices. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 83, 52–56. https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=c108e188-77d2-40ed-af1e-46ba0dd57425%40redis

- Rivas‐Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., Schwartz, A. J., Umana-Taylor, S. F., Yip, T., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12200

- Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709

- Robinson-Ervin, P., Cartledge, G., Musti-Rao, S., Gibson, L., & Keyes, S. E. (2016). Social skills instruction for urban learners with emotional and behavioral disorders: A culturally responsive and computer-based intervention. Behavioral Disorders, 41(4), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.17988/bedi-41-04-209-225.1

- Shi, Y., & Zhu, M. (2022). Equal time for equal crime? Racial bias in school discipline. Economics of Education Review, 88, 102256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102256

- Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta‐analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22679

- Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school‐based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

- US Department of Education. (2022). Office for civil rights, 2017-2018 civil rights data collection[infographic]. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/suspensions-and-expulsion-part-2.pdf