?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Rising support for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, paired with the considerable buying power of this group, has triggered increasing interest from marketers in the gay and lesbian market. Many companies have developed advertising with homosexual imagery to better target this group as well as the mainstream market. The findings on the persuasive effects of homosexual imagery are mixed and do not provide insights on whether and when homosexual imagery in advertising supports persuasion. To resolve the inconsistencies in findings of prior research, this article presents a meta-analysis on the effects of homosexual imagery. The integrated effect size suggests that the net persuasive effect between homosexual and heterosexual imagery does not differ. We find, however, that homosexual consumers show negative responses to heterosexual imagery. Furthermore, the moderator analysis suggests that incongruence between imagery, consumer characteristics, cultural values, explicitness of imagery, endorser gender, and product type results in unfavorable responses to homosexual advertising imagery. These findings provide guidelines for future research and implications for advertisers who intend to address consumers of various sexual orientations.

In recent decades, support for homosexuality in society has increased considerably (Ghaziani, Taylor, and Stone Citation2016). Many Western societies have strengthened equal rights and opportunities for homosexual citizens. The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community is a market segment with substantial buying power. The collective buying power among all LGBT Americans was estimated to be nearly $1 trillion in 2017, thus rivaling the disposable income of all other American minority groups (Chesney Citation2017). Increasing support for the LGBT community and the collective buying power of this group has triggered the interest of marketers and advertisers in the gay and lesbian market. Many companies in Western societies such as the United States currently use advertising featuring homosexual imagery—that is, advertisements featuring lesbian or gay endorsers (e.g., same-sex couples) or other gay or lesbian iconography, such as a pink triangle or a rainbow flag (Angelini and Bradley Citation2010). While homosexual imagery in advertising has been traditionally confined to niche markets, it is appearing more and more often in mainstream media targeted at both homosexual and heterosexual consumers (Read, van Driel, and Potter Citation2018). Despite this increase in gay-themed advertising, much is still unknown about its effects. Several practical examples indicate that using homosexual imagery in advertising that targets both homosexual and heterosexual consumers can be successful; for example, Swedish furniture store IKEA has successfully advertised kitchens with gay couples and thus increased the appeal of their products to both homosexual and heterosexual consumers (Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008). Burger King’s 2014 pride campaign, which featured the “Proud Whopper” served in a rainbow-colored wrapper that had printed on it the phrase “We are all the same inside,” received overwhelmingly positive responses across all social media platforms (Snyder Citation2015). However, using homosexual imagery in advertising can bear some risks. Suitsupply, a global company that provides exclusive suits for men, launched a campaign with two men kissing in an erotic way. The explicit homosexual imagery in this campaign resulted in a backlash, with many customers unfollowing the company on its social media channels (Paauwe Citation2018).

Several studies have addressed the persuasive effects of homosexual imagery in advertising by comparing heterosexual and homosexual imagery, or gay and lesbian imagery. The findings are mixed and do not provide clear evidence as to whether and which homosexual imagery in advertising supports persuasion (Ginder and Byun Citation2015). Research has further suggested that the effects are conditional and depend, among other things, on characteristics of the ads and the consumers (Dotson, Hyatt, and Thompson 2009; Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005). Yet findings from the studies are mixed. For instance, previous research investigated the effects of explicitness and endorser gender of homosexual imagery on consumer responses. While some studies demonstrated heterosexuals’ preference for implicit over explicit homosexual imagery (Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005; Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008), other studies showed this effect can be reversed (e.g., Um Citation2016). Findings on the preference of homosexual consumers for either explicit or implicit homosexual imagery are also mixed (Dotson, Hyatt, and Thompson 2009; Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005). Responses to depictions of homosexuality depend on society’s general support of and openness to homosexuality (Herek and McLemore Citation2013). Support for homosexuality in a particular society changes over time; thus, support for homosexuality varies not just across societies but also over time. However, research on homosexual imagery in advertising has ignored the cultural and temporal context, despite acknowledging it as a potential moderating variable (Åkestam Citation2017).

To address these inconsistent findings and to provide better input for advertisers who intend to use homosexual imagery to address either homosexual consumers exclusively or all consumers, regardless of their sexual orientation, this article offers a meta-analysis of prior research on the persuasive effects of homosexual imagery. More specifically, we pursue the following objectives: (1) to empirically assess the net persuasive effects of both homosexual versus heterosexual imagery in advertising, and of gay versus lesbian imagery in advertising, and (2) to uncover the conditions under which either or both imageries lead to more persuasion and benefits advertising effectiveness. These findings solve inconsistencies in prior research, provide guidelines for future research, and propose implications for marketers and advertisers who intend to address consumers of different sexual orientations.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The considerable size and collective purchase power of the market segment of homosexual consumers is attractive to marketers. Although several studies have portrayed the homosexual, primarily gay, consumer as affluent, well educated, with specific buying preferences, and as someone who differs from the general heterosexual consumer population (DeLozier and Rodrigue Citation1996), this portrayal has been questioned, because the data used in these studies are not necessarily representative of the rich diversity of the LGBT community. Homosexuals who are open about their sexual orientation and are proud to self-identify as gay or lesbian are often more economically stable and from higher social classes (Badgett Citation2001). The portrayal of homosexual consumers that is painted by such data and often emphasized through images in the media seems to define what it means to be gay, and thus might stereotype an idealized gay consumer (Ginder and Byun Citation2015; Kates Citation2002). Hence, while the homosexual market is attractive to marketers due to its size and collective buying power, it is unclear whether the average homosexual consumer does indeed differ substantially from the average heterosexual consumer.

Marketers who use homosexual imagery to address either homosexual consumers exclusively or in mainstream advertising face a difficult situation, particularly because of the dynamics of support for homosexuality over time and across different countries. Similar situations and developments occurred in the past for portrayals of other minority groups in advertising, such as African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans in advertising in the United States (Taylor, Lee, and Stern Citation1995; Taylor and Stern Citation1997). Initially, many companies were afraid that their brands would be perceived as “Black” when including African Americans in their marketing strategy (Um Citation2014). As support for minority groups increased, their portrayals appeared more often in advertising, although they were initially often depicted in stereotypical ways; however, stereotyping has decreased over time (Stevenson and Swayne Citation2013). As for the effects of depictions of these ethnic minorities in advertising, older studies often show that ethnic majority and minority consumers tend to show positive reactions toward endorsers of similar ethnic origin and negative reactions to endorsers of dissimilar ethnic groups (e.g., Aaker, Brumbaugh, and Grier Citation2000). More recent studies, however, show that majority group consumers responded equally well to ethnic minority and majority endorsers (e.g., Elias and Appiah Citation2010). Increasing positive reactions of majority consumers toward minority portrayals in advertising correlate with increasing acceptance, visibility, and support for minority groups in society. Modern societies with high levels of wealth and education develop a higher level of social trust, which, in turn, reduces minority stereotypes and offsets the negative impact of any perceived threats through high diversity in society (Dinesen and Sønderskov Citation2015).

Societal dynamics and variations in support for homosexuality over time and across countries are reasons why findings on the net persuasive effects of homosexual imagery (i.e., the average effect) in prior advertising studies are mixed. For instance, about 10 years ago Dotson, Hyatt, and Thompson (2009) found that ads featuring homosexual imagery led to less favorable ad evaluations than heterosexual imagery in the United States, while Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen (Citation2017) more recently revealed positive effects of homosexual portrayals in a study conducted in Sweden.

Knowing the net persuasive effect of homosexual imagery in advertising can provide a useful albeit very general benchmark and guideline for advertisers that indicates whether homosexual imagery in advertising generally benefits persuasion. Nevertheless, neither researchers nor practitioners know the net effects of using homosexual imageries—that is, the effect of such imagery when targeting consumers regardless of their sexual orientation. We therefore put forward the following research question:

RQ1: What is the net persuasive effect of using homosexual imagery in advertising?

Mixed findings in prior studies indicate that the persuasive effects of such homosexual imagery varies considerably and requires further explanation. To explain the variation in persuasive effects of homosexual imagery, and to provide more detailed benchmarks and guidelines on when and how to use homosexual imagery, we use a congruency framework that is commonly applied to explain advertising effects of minority group advertising to minority and majority consumers (e.g., De Meulenaer et al. Citation2018; Orth and Holancova Citation2004).

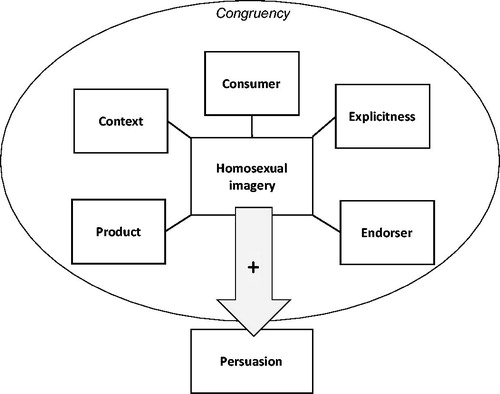

The congruency framework refers to the idea that “changes in evaluation are always in the direction of increased congruity with the existing frame of reference” (Osgood and Tannenbaum Citation1955, p. 43). Congruency issues arise if an input that relates to two or more objects of judgments is received. In the case of homosexual imagery in advertising, objects of judgments could be the endorser and the product, or the imagery and the values, schemas, and expectations of the receiver. Persuasive effects are more likely if both objects are perceived to be congruent, for instance, if the advertising imagery transports values and schemas that are congruent with the receivers’ values, schemas, and expectations, and if the imagery is congruent with other elements of the persuasion process (in particular, the product, endorsers, and message). Because values and schemas are embedded in a cultural and temporal context, homosexual imagery congruity also relates to cultural values and schemas related to homosexuality that vary over time (Herek and McLemore Citation2013). depicts the congruency elements that are assumed to moderate the relationship between homosexual imagery and persuasion. In the following section, we first derive hypotheses for the persuasive effects of homosexual versus heterosexual imagery, followed by hypotheses for the effects of gay versus lesbian imagery.

EXPLAINING THE PERSUASIVE EFFECTS OF HOMOSEXUAL VERSUS HETEROSEXUAL IMAGERY

Congruency with Consumers

A challenge for advertisers who use homosexual imagery is the different reactions it might trigger for homosexual and heterosexual consumers. The idea of congruency between homosexual imagery and consumers is backed by theories referring to ingroup–outgroup distinctions, targeting, and social identity that have been used to explain how consumers of different sexual orientations respond to homosexual imagery in advertising. The most prominent approach is social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1985), which suggests that group membership provides social identity and enhances the group members’ self-esteem by differentiating themselves from members of the outgroup. Outgroup members are incongruent objects of judgments for the ingroup and are evaluated more negatively to maintain the superiority of the ingroup. Homosexual (versus heterosexual) consumers who are exposed to homosexual (versus heterosexual) imagery in advertising will exhibit ingroup favoritism and evaluate the imagery as congruent to the ingroup and thus more favorably, thus increasing its persuasiveness. On the other hand, heterosexual consumers should prefer advertisements with heterosexual imagery (e.g., Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005).

H1: Homosexual imagery is more persuasive for homosexual consumers compared to heterosexual consumers.

Congruency with Contexts

Public acceptance of homosexuality in many societies has risen dramatically over the past two decades (Ghaziani, Taylor, and Stone Citation2016). This is evidenced, for instance, by more favorable responses to survey questions about same-sex marriage (Lax, Phillips, and Stollwerk Citation2016), reduced institutional and corporate barriers to equality of sexual minorities (Herek and McLemore Citation2013), and increasing representations of homosexual people in media and advertising (Bond Citation2014). These changes indicate increasing congruency between homosexuality—which also includes the portrayal of homosexuality in advertising—and public opinion. Increasing congruency suggests more positive evaluations of homosexual imagery in advertising over time.

Positive changes in the support of homosexuality have helped many more homosexual consumers express their sexual identity and preferences. The extant literature shows that disclosing one’s homosexual identity is positively related to homosexuals’ satisfaction with life, positive affect, and self-esteem (Beals, Peplau, and Gable Citation2009) and negatively related to self-stigma (Herek, Gillis, and Cogan Citation2009). Research further demonstrates that homosexual role models in the media can positively influence homosexuals’ identities and self-realization and serve as sources of pride, inspiration, and comfort (Gomillion and Giuliano Citation2011). Thus, the increasing congruency between homosexual imagery and public opinion might benefit homosexual consumers more than heterosexual consumers, and homosexual consumers might more positively react to more homosexual imagery in advertising over time as a reflection of increasing societal support and marketers’ appreciation of homosexuality.

H2: The effect of homosexual imagery becomes more persuasive over time, particularly for homosexual consumers.

Cultural values vary among societies and are more or less congruent with homosexuality and homosexual imagery. A relevant and important cultural value in the context of homosexuality refers to the cultural dimension of masculinity, because it has been shown to correlate with the support of homosexuality in a country (Hofstede Citation1998). Masculinity revolves around the emotional role distribution between genders (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010). Masculine cultures possess clearly distinct gender roles, and men in these cultures are expected to be tough and assertive. Feminine cultures have overlapping social gender roles and expect similar characteristics from men and women. Masculine-oriented countries reject homosexuality because it is a threat to masculine norms. Because gays and lesbians do not adhere to gender-role expectations of masculine cultures, they find more support in feminine cultures than in masculine ones. In fact, the first countries to legalize same-sex marriage (e.g., the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway) all score high in femininity. The more masculine the cultural value context is, the less congruent it is with homosexual imagery and the less supported and thus persuasive homosexual imagery in advertising is likely to be.

The effect described is particularly strong for heterosexual consumers because sexual prejudice (i.e., negative attitudes toward individuals based on their sexual attractions, behaviors, or orientation) toward homosexuals is stronger in masculine societies where a homosexual orientation contradicts the masculine gender norms (Herek and McLemore Citation2013). Nonconformity to the cultural norms of masculinity leads to the expression of sexual prejudices against homosexuals, resulting in more negative reactions to homosexual imagery in advertising. The reactions of heterosexuals in masculine countries toward homosexual imagery oppose the reactions of homosexuals who, in light of being rejected by masculine countries, might deploy strategies of “identity for critique” to confront and problematize the gender norms and values of the dominant, heteronormative culture (Bernstein Citation1997) and to celebrate differences from the heterosexual majority (Ghaziani, Taylor, and Stone Citation2016). Hence, the hypothesized effect of incongruency between cultural values and homosexual imagery that leads to less persuasiveness applies particularly to heterosexual consumers but not necessarily to homosexual consumers.

H3: The effect of homosexual imagery becomes less persuasive as the masculinity of the culture increases, for heterosexual consumers in particular.

Congruency with Explicitness

Prior research suggests that implicit homosexual imagery—that is, imagery that avoids explicit and unambiguous references to homosexuality and/or includes homosexual iconography and symbolism such as rainbow flags or pink triangles (Puntoni, Vanhamme, and Visscher Citation2011; Um Citation2016)—is appreciated more by general audiences than is explicit imagery (Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005). The use of implicit homosexual advertising imagery is more in line and congruent with the schema and expectations of a mainly heterosexual audience. The schema congruency results in favorable evaluations from the general audience, because the heterosexual majority of consumers can identify better and understands implicit imagery better than explicit homosexual iconography (e.g., erotic gestures or kissing), as explicit homosexual behavior is still less commonly practiced than implicit homosexual behavior.

Because implicit homosexual imagery does not fully express homosexuals’ individual sexual and gender identities, but rather seems to hide it, homosexual consumers feel less targeted (Oakenfull Citation2007). The advertising is less appealing to them, and they feel unappreciated as a unique and valuable consumer segment. Implicit imagery is less congruent with their schemas and expectations of being fully accepted and appreciated, which leads to more negative evaluations of implicit homosexual imagery in advertising. Explicit imagery, on the other hand, has the opposite effect, as it directly relates to and emphasizes the identities of homosexual consumers and is therefore more congruent with their schemas.

H4: (a) Implicit homosexual imagery is less persuasive for homosexual consumers, and (b) explicit homosexual imagery is more persuasive for homosexual consumers.

Congruency with Endorsers

Findings about male and female endorsers in homosexual advertising are ambiguous (Ginder and Byun Citation2015). While gay endorsers are more common (Um et al. Citation2015), they still can negatively affect heterosexual consumers because of the incongruity with their schemas and expectations: Consumers more likely expect a heterosexual endorser than a gay endorser. Oakenfull and Greenlee (Citation2004) have suggested using lesbian endorsers because there is a general lack of lesbian visibility, and they might be perceived as less incongruent, because heterosexual consumers’ schemas and expectations regarding lesbian endorsers are less negatively predetermined and thus more flexible. Indeed, extant research demonstrated that heterosexuals hold more hostile attitudes and show more negative reactions to gay men compared to lesbians. While heterosexuals express more negative attitudes toward homosexual individuals of their same sex, this pattern is more pronounced among heterosexual males than females (Herek Citation2002). As a result, gay endorsers meet more negative reactions than lesbian endorsers among heterosexual consumers. In fact, lesbian imagery provides an erotic value to heterosexual males, making it more appealing to them (Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2004). Even if heterosexual women do not react differently to gay or lesbian endorsers, the differential effect of heterosexual men to either endorser leads to the following assumptions:

H5: (a) Homosexual imagery depicting only gay endorsers is less persuasive to heterosexual consumers; (b) homosexual imagery depicting only lesbian endorsers is more persuasive to heterosexual consumers.

Congruency with Product

While prior research in homosexual imagery has studied the congruence between imagery and consumers, research on the role of products is scarce. A congruency perspective suggests that the persuasiveness depends on the fit of the product with the imagery as perceived by the consumers (Knoll and Matthes Citation2017). Homosexual consumers are often associated with having affluent, lavish, and trendy lifestyles (Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015) that involve the consumption of high-involvement and hedonic products. In particular, gay men are often seen as “connoisseurs of consumption” (Yaksich Citation2008). Gay characters and personalities from various TV programs, such as Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, serve as experts and reference for consumers to extract knowledge about proper home decor, cooking, fashion, and forms of entertainment. Hence, homosexual imagery is perceived as more congruent with high-involvement or hedonic products and thus more persuasive.

H6: Homosexual imagery is more persuasive for (a) high-involvement products and (b) hedonic products.

PERSUASIVE EFFECTS OF GAY VERSUS LESBIAN IMAGERY

Most prior research has focused on effects of homosexual imagery without further distinguishing between gay and lesbian consumers, although the literature suggests substantial differences in the perception of either group by the heterosexual majority (Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015; Ghaziani, Taylor, and Stone Citation2016). If they are perceived differently, they are also perceived as more or less congruent with consumers’ schemas and expectations. Hence, different effects elicited from gay and lesbian imagery types can be expected as well.

Congruency with Consumers

For gay and lesbian consumers, sexual orientations play different roles in defining their identities; for instance, gender is more identity defining than sexual orientation for lesbians in comparison to gay men (Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008). Therefore, homosexual advertising does not follow a one-size-fits-all approach but speaks primarily to either gays or lesbians, depending on the homosexual imagery. Assuming that congruency between the imagery and consumer schemas and expectations increases persuasion, gender-emphasizing homosexual imagery should have different effects for lesbians and gay men. Lesbian imagery should be more appreciated by lesbian consumers and thus be more persuasive for them; and vice versa for gay consumers.

H7: The difference in persuasive effect of lesbian over gay imagery is (a) negative for gay men consumers and (b) positive for lesbian consumers.

Congruency with Contexts

Homosexuals have traditionally been portrayed in the media by male characters, leading to more awareness of gay male, compared to lesbian, imagery by society. As a result, the appearance of gay male imagery is more congruent with what consumers expect once they are exposed to homosexual imagery. However, more lesbian characters have been portrayed in recent years (Schwartz Citation2016). Although homosexual advertising still uses more gay male imagery than lesbian imagery, and lesbians are still significantly underrepresented in homosexual advertising (Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2004), this gap seems to be narrowing (Ginder and Byun Citation2015). These changes suggest that expectations and schemas toward gay male and lesbian imagery became more similar and that any congruency effects that lead to persuasion should have become more similar over time, too.

H8: The difference in persuasive effects of lesbian over gay male imagery has decreased over the years.

Masculine-oriented countries reject homosexuality because it is a threat to masculine norms and gender-role expectations and beliefs; that is, homosexuality and homosexual imagery are incongruent with values, schemas, and expectations of consumers in masculine countries (Herek and McLemore Citation2013). Research suggests that gay men deviate more from traditional gender-role expectations than lesbians do (Blashill and Powlishta Citation2009). Gay men are viewed as less masculine and more feminine than heterosexual men and as similarly feminine as heterosexual women. While lesbians are considered to be more masculine than heterosexual women and gay men, they are still perceived as less masculine than heterosexual men. Therefore, gay males contradict traditional gender-role expectations and schemas in masculine-driven countries more than lesbians do. This incongruency leads to more unfavorable persuasive responses to gay male imagery compared to lesbian imagery in these countries.

H9: The difference in persuasive effect of lesbian over gay imagery increases with the masculinity of the culture.

Congruency with Explicitness

Because lesbians are less visible in some societies, and might even arouse male heterosexuals’ erotic fantasies in others (Reichert Citation2001), explicit lesbian imagery is considered less incongruent with consumers’ expectations and schemas; thus, lesbian imagery is more acceptable than explicit gay male imagery. More congruency can be expected for implicit imagery of gay male imagery. Implicit homosexual imagery features more ambiguous or subtle references to homosexuality, making both gay male and lesbian sexual identities less salient and thus both more congruent with consumers’ schemas and expectations. Any difference in evaluating implicit lesbian versus gay male portrayals is reduced, leading to similar persuasive effects of implicit gay male and lesbian imagery.

H10: The difference in persuasive effect of lesbian over gay male imagery is (a) weaker for implicit imagery and (b) stronger for explicit imagery.

Congruency with Product

Gay male consumers are more likely to be associated with an expensive taste and an affluent and hedonistic lifestyle than are lesbian consumers (Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015; Kates Citation2002). Advertising that incorporates gay male imagery for high-involvement and hedonic products is therefore more congruent with the stereotype of gay males as fashion-conscious, high-income, and high-spending consumers (Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015), while it is less congruent with the expectations consumers have toward lesbian consumers. As a result, gay male imagery is more persuasive than lesbian imagery for these products.

H11: The difference in persuasive effect of lesbian over gay male imagery is weaker (i.e., becomes negative) for (a) high-involvement products and (b) hedonic products.

We do not formulate hypotheses for endorser congruency and gay male versus lesbian imagery because the empirical studies do not show any variation regarding this variable (i.e., all experiments show both lesbian and gay male endorsers). provides an overview of the research question and all hypotheses.

TABLE 1 Overview of Research Question and Hypotheses of the Meta-Analysis.

METHOD

Study Retrieval and Coding

This meta-analysis compiles papers that investigate the influence of homosexual imagery in advertising on consumer responses. To this end, we performed an exhaustive search of published and unpublished papers that empirically tested the effect of advertising that includes homosexual stimuli. First, we performed a keyword search of electronic databases (such as Web of Science, EBSCO, SSRN, ProQuest, and Google Scholar) and relevant conference proceedings (conferences by the American Advertising Academy, Association for Consumer Research, and European Academy of Advertising) using the following keywords: “homosexual,” “gay,” “lesbian,” “queer,” “sexual orientation,” “LGBT,” and “sexual minority,” in combination with “marketing,” “advertising,” “advertisement,” “ad,” “consumption,” “consumer,” and “customer.” Second, we searched a review article (Ginder and Byun Citation2015) and two seminal and highly cited papers studying the effects of homosexual advertising imagery (Bhat, Leigh, and Wardlow Citation1998; Grier and Brumbaugh Citation1999), examining their references and applying an ancestry tree search by searching for all papers referring to these papers. Third, we performed a manual search of the journal outlets that turned out to be major sources for journal articles dealing with gay or lesbian advertising stimuli. Fourth, we reviewed the reference lists in all the previously obtained papers. The compilation procedure is in line with that of prior meta-analyses in advertising research and recommendations in the literature (e.g., Capella, Taylor, and Webster Citation2008; Eisend Citation2017a; Shen, Sheer, and Li Citation2015) and includes all papers that were available as of July 2018.

We included all papers that reported on empirical studies based on samples of (prospective) consumers and that quantitatively investigated the effects of advertising, comparing homosexual imagery with heterosexual imagery as well as gay male imagery with lesbian imagery on consumer response variables. We excluded papers that did not provide sufficient data for the purpose of our meta-analysis, such as those which lacked sufficient statistical information to calculate an effect size and for which the necessary information could not be retrieved from the authors. Apart from these exclusions, we considered any papers written in English that provided the appropriate empirical data. All relevant papers are based on experimental studies.

To avoid duplications in our database, we proceed in the following manner. A document with original analysis and findings by the authors (e.g., journal article, working paper, conference paper) is called a “paper.” Some papers analyze more than one distinct data set (e.g., a paper with several experiments), while some data sets are analyzed in more than one paper (e.g., an empirical study that is published in a dissertation and as a journal paper). To avoid duplications, our analysis is based on data sets. Each data set can provide single or multiple effects.

Two coders independently coded the papers and assigned the consumer response variables investigated in these papers to the following seven categories:

attitude toward the ad (i.e., evaluation of the advertisement),

attitude toward the brand (i.e., evaluation of the sponsored brand or product),

diversity perceptions (i.e., perception and beliefs of company diversity and specific targeting),

purchase and behavioral intention (i.e., intention to purchase the brand or to engage in purchase- and brand-related behavior),

positive emotions, (i.e., consumers’ positive emotional responses to the ad),

negative emotions (i.e., consumers’ negative emotional responses to the ad), and

attention (i.e., consumers’ attention triggered by the ad).

Another category, memory, was excluded from further analysis because only one data set in one paper provided two memory effects. The coder agreement rate was above 97%. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion between the coders. The final database includes 356 effect sizes from 36 papers that use 38 distinct data sets (see Appendix). The database of this meta-analysis includes journal articles, working papers, unpublished theses, and conference proceedings, thus reducing the risk of a biased representation of the state of research because of the source of publication (Eisend and Tarrahi Citation2014).

Effect Size Computation and Coding

The effect size is measured by the correlation coefficient, which is easy to interpret. A positive correlation coefficient indicates that homosexual imagery (compared to heterosexual imagery) increases the consumer-response variable, and vice versa for a negative correlation coefficient. When comparing gay male versus lesbian imagery, a positive correlation coefficient indicates that lesbian imagery (compared to gay male imagery) increases the response variable. For studies that reported other measures (e.g., Student’s t, mean differences), those measures were converted to correlation coefficients following common guidelines for meta-analysis (Lipsey and Wilson Citation2001). The correlations were adjusted for measurement error of the dependent variable following the procedure proposed by Hunter and Schmidt (Citation2004). When a study did not report on reliability, we used the mean reliability for that variable across all studies.

Integration of Correlation-Based Effect Sizes

To capture the net persuasive effect of homosexual imagery (compared to heterosexual imagery) on each consumer-response variable, the correlation-based effect sizes were integrated and an average estimate was computed. We integrate dependencies between multiple correlation estimates from the same data set using the following approach. When a data set presented findings for different consumer-response variables, the findings were treated as independent because we integrated and analyzed the correlation estimates for each consumer-response variable separately. Some data sets reported multiple and thus dependent relevant effects for the same consumer-response variables. We account for the dependencies of correlation estimates and the nested structure of meta-analytic data by using multilevel or hierarchical linear modeling (Raudenbush and Bryk Citation2002). By specifying that correlation estimates are clustered under the higher-level unit of a data set, multilevel modeling addresses the dependence problem. We estimate the following model:

where i = 1, 2, 3 … correlation estimates and j = 1, 2, 3 … data sets. This formula estimates the average correlation ρ, the deviation of the average correlation of a data set from the grand mean (μj), and the deviation of each correlation in the jth data set from the grand mean (μij). The two latter terms have a variance of σj2 and σij2, respectively. The error term eij is the known sampling error for each effect size and is supplied as a data input.

We computed fail-safe Ns to address publication bias. For any relationship of interest, fail-safe N represents the number of additional nonsignificant correlations needed to render the integrated correlation for that relationship nonsignificant at p = .05. We calculated the fail-safe Ns for all integrated correlations that turned out to be significant at p < .05 by using the correlation estimates that were adjusted for measurement error. Furthermore, we provided a homogeneity test as an aid to decide whether observed correlations are more variable than would be expected from sampling error alone.

Meta-Regression

If the homogeneity test indicates heterogeneity, and the variation in correlations cannot be explained by sampling error alone, we attempt to explain the variation by moderator variables as suggested by the hypotheses. provides an overview over all moderator variables, their description and operationalization, coding, as well as data characteristics. All high-inference moderators—that is, moderators that allow for individual interpretations during coding, such as whether a product is a high-involvement product—have been coded by two coders. The agreement rate was sufficiently high (), and inconsistencies were resolved by discussion. Masculinity index and year of data collection are considered low-inference coding.

TABLE 2 Overview and Description of Moderator Variables.

We assess the influence of these variables on the correlation-based effect sizes through a multivariate analysis that uses a conditional model in hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; that is, predictor variables are added to the “intercept-only” model). To ensure the robustness of the model, which requires a sufficient number of correlations and data sets, as well as a reasonable ratio of correlations per data set, we follow the approach in other meta-analyses (e.g., Jeong and Hwang Citation2016; O'Keefe Citation2013) and combine effect sizes related to attitudes and intentions into a broader category of persuasion. The approach is justified, as the attitude and intention effect sizes do not differ significantly (see results in ). It allows for testing the simultaneous influence of multiple moderator variables.1 The first regression model with 17 estimated parameters is applied to 217 effect sizes that are clustered within 33 different data sets. The second regression model with nine estimated parameters is applied to 87 effect sizes that are clustered within 14 different data sets.

TABLE 3 Effects of Homosexual Imagery in Advertising: Integration of Correlation-Based Effect Sizes.

A multilevel model that includes influencing variables is called a conditional model. The conditional model is a mixed-effects model, as fixed effects for the influencing variables are considered in addition to random components. The estimated model for the persuasive effects of homosexual versus heterosexual imagery can be expressed as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where rij denotes the ith correlation reported within the jth data set. EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) is the level-one equation that describes the effect of moderator variables and their interactions that vary within data sets (see for moderator variables). EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) describes the effects of the continuous variables’ year of data collection (U1j) and masculinity index (U2j) that varies between studies on the intercept β0j and on the regression coefficient β1j in the level-one equation, where ν0j is the study-level residual error term. Both continuous variables were mean centered.

The estimated model for the persuasive effects of gay male versus lesbian imagery can be expressed in the following manner:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Before estimating an HLM, we conducted several checks to ensure the robustness of the model, particularly to reduce collinearity as a major issue in metaregression. First, we examined the bivariate correlations among the potential covariates. Second, we computed variance inflation factors (VIFs). All correlations were below 0.5, and all VIF values were acceptable (<2.5). Further, we checked for outliers but found none.

RESULTS

Integrated Effect Size Estimates

presents an overview of the integrated correlations. The upper part of the table presents the integrated findings of the effects of homosexual versus heterosexual imagery; the lower part presents the integrated findings of the effects of lesbian versus gay male imagery. Similar to other meta-analyses in advertising research with exploratory questions and two-sided tests, we interpret findings for p < 0.1 as relevant (Eisend Citation2017b; Sethuraman, Tellis, and Briesch Citation2011).

Only two effects are significant at p < 0.1. Homosexual imagery leads to less attention but to increased diversity perceptions. The fail-safe N indicates that the diversity perception finding is robust and does not suffer from publication bias, following the rule of thumb that the fail-safe N should be greater than five times the number of effect sizes plus 10. None of the other consumer-response variables reveals a significant result, indicating that, in general, the persuasion effects of advertisements with either homosexual or heterosexual imagery or with either lesbian or gay male imagery do not differ. However, the homogeneity test indicates that the integrated correlations are heterogeneous (with one exception: attention), and that the effects are conditional. The conditions can be investigated, and the heterogeneity can be further explained by moderator variables.

Moderator Analysis: Metaregression Results

provides the results of the metaregression model for the persuasive effects of homosexual versus heterosexual imagery in advertising. Homosexual advertising is more persuasive if the sample consists of homosexual consumers (predicted value of the effect size: 0.471), but there is no difference for heterosexual consumers between homosexual and heterosexual imagery (−0.023). This finding supports hypothesis 1.

TABLE 4 Explaining the Variation in Persuasion Effects of Heterosexual versus Homosexual Imagery: Metaregression Model.

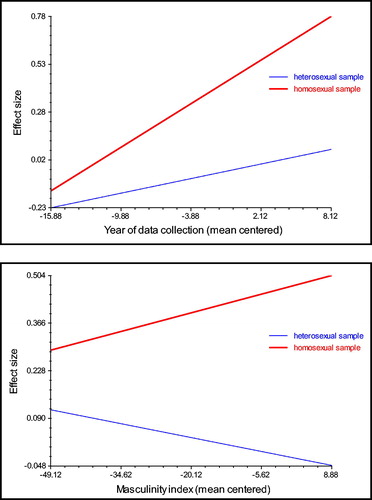

The year of data collection shows a main effect: The persuasive effect of homosexual imagery has increased over time. This effect is qualified by an interaction effect that is depicted in . The increased persuasive effect of homosexual imagery is driven by the responses of homosexual consumers rather than heterosexual consumers, in line with hypothesis 2. Masculinity shows not a main effect but an interaction effect, which is in line with hypothesis 3 (see ): The difference in effects between homosexual and heterosexual imagery increases with cultural masculinity, such that the cultural masculinity effect mainly applies to heterosexual consumers.

FIG. 2. Interaction effects for Year of data collection × Consumer sexual orientation and Masculinity index × Consumer sexual orientation on the persuasive effects of heterosexual versus homosexual imagery.

Regarding advertising imagery, implicit homosexual imagery leads to stronger persuasive effects of homosexual imagery but not to an interaction effect with homosexual consumers, thus rejecting hypothesis 4(a). There is no main effect of explicit homosexual imagery, but there is an interaction effect of explicit imagery with consumer sexual orientation, supporting hypothesis 4(b): Explicit homosexual imagery shows the strongest persuasive effects for homosexual consumers. Using either male or female homosexual endorsers exclusively does not show a main effect, but both endorser types show interaction effects with consumers’ sexual orientation in line with hypothesis 5(a) and hypothesis 5(b). For heterosexual consumers, a gay male endorser decreases the effect of homosexual imagery, while a lesbian endorser increases the effect of homosexual imagery. We did not find an effect for high-involvement products, rejecting hypothesis 6(a), but we did find an effect for hedonic products, in line with hypothesis 6(b). The effect of homosexual imagery becomes stronger for hedonic products.

provides the results of the metaregression model for the persuasive effects of lesbian versus gay male imagery in advertising. No effects appeared for gay male consumers, rejecting hypothesis 7(a), but lesbian consumers are more persuaded by lesbian imagery than by gay male imagery, which is in line with hypothesis 7(b). While there is no year effect (rejecting hypothesis 8), the positive sign of the masculinity index shows that with increasing cultural masculinity, lesbian imagery becomes more persuasive than gay male imagery, which is in line with hypothesis 9. Implicit homosexual imagery leads to more persuasive effects of gay male imagery compared to lesbian imagery, in line with hypothesis 10(a). We did not find any effects for explicit homosexual imagery, thus rejecting hypothesis 10(b). While hedonic products do not show any effect, rejecting hypothesis 11(b), high-involvement products are more persuasive when using gay instead of lesbian imagery, which is in line with hypothesis 11(a).

TABLE 5 Explaining the Variation in Persuasion Effects of Gay versus Lesbian Imagery: Meta-regression Model.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the meta-analysis was (1) to empirically assess the net persuasive effects of homosexual versus heterosexual and gay male versus lesbian imagery in advertising and (2) to uncover the conditions under which either or both imageries lead to more persuasion, and thus benefits advertisers and marketers.

As for the first goal, the findings show that the net persuasive effect between homosexual and heterosexual imagery, as well between gay male and lesbian advertising, does not differ. Some prior research has suggested that homosexuals in advertising could negatively affect heterosexual consumers, but the metaregression findings show that, when differentiating between homosexual and heterosexual consumers, heterosexual consumers do not react differently to homosexual or heterosexual imagery in advertising. The findings are in line with a positive social (priming) effects of homosexual imagery: Diversity in advertising portrayals can prime most consumers to think about others, which leads to perceived social connectedness, empathy, and the appreciation of diversity in advertising imagery (Åkestam, Rosengren, and Dahlen Citation2017). Homosexual consumers, however, are more persuaded by homosexual than heterosexual portrayals. Rather than the negative reactions of heterosexual consumers that has been suggested in prior research (e.g., Angelini and Bradley Citation2010; Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008; Um Citation2014), we found that homosexual consumers react negatively toward heterosexual imagery.

As for our second goal, the findings reveal several insights into when homosexual portrayals are persuasive. Supporting the idea of congruency, the moderator analysis suggests that homosexual portrayals are more persuasive for homosexual consumers than for heterosexual consumers, and this effect has increased over the years. These responses suggest a shift in research focus and managerial implications for the future.

We further found that homosexual portrayals lead to negative reactions by heterosexual consumers in highly masculine countries. Interestingly, we found an opposite effect for homosexual consumers in highly masculine countries, who are even more persuaded by homosexual imagery than their counterparts in more feminine countries. Research on social movements reinforces the pivotal role of collective identities for activists and the tension between emphasizing similarities to (heterosexual) majorities and celebrating differences from them (Ghaziani, Taylor, and Stone Citation2016). Because homosexuality is less supported in masculine countries, homosexuals seem to reinforce and express their collective sexual identity by appreciating advertising imagery that clearly differs from the norm of the heterosexual majority.

Implicit imagery works better for homosexual portrayals in a general population, while homosexual consumers prefer explicit imagery. The favorable responses of the general audience to implicit homosexual imagery is in accordance with the suggestion to use it to create “win-win advertising messages for both the heterosexual and homosexual consumer markets” (Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008, p. 197). However, homosexuals’ preference for explicit over implicit imagery contrasts previous research findings that revealed no differences in reactions to both types of homosexual imagery (e.g., Oakenfull and Greenlee Citation2005; Oakenfull, McCarthy, and Greenlee Citation2008). Considering the increasing support for homosexuality in society and homosexuals’ growing self-confidence as individuals and consumers, explicit homosexual imagery seems to better address homosexual consumers’ individual sexual and gender identities, leading to positive targeting effects.

Lesbian endorsers are preferred over gay male endorsers by heterosexual consumers, in line with suggestions by Oakenfull and Greenlee (Citation2004), who recommend using lesbian endorsers as they lead to more positive responses by heterosexual consumers. Given the previously mentioned favorable responses of the general audience to implicit homosexual imagery, the degree of intimacy or eroticism of lesbian imagery, also referred to as “lesbian chic” (Reichert Citation2001), might be perceived as less explicit and particularly attract heterosexual consumers without causing negative responses due to excessive sexualized portrayals.

If products are hedonic, homosexual portrayals work better, which corresponds to the association of gay male consumers with lavish and hedonistic lifestyles and consumption behaviors. The findings show that the congruence between lifestyle- and consumption-related stereotypes of homosexuals and homosexual portrayals can result in positive advertising imagery evaluations.

The findings further reveal differences in persuasion between gay male and lesbian imagery. The difference is stronger in masculine societies that prefer lesbian over gay male imagery. Lesbian consumers are more persuaded by lesbian imagery, but there is no difference for gay male consumers. While gay men rely more on homosexuality as an identity-defining trait and identify with the homosexual community as a whole, lesbians’ identities are based on both sexual orientation and gender and are therefore distinct from those of gay men (Oakenfull Citation2013). Lesbians are confronted with multiple societal challenges that stem from being female and homosexual. Hence, they identify more with gender-emphasizing lesbian advertising imagery as a reflection of societal appreciation and an identity-building mechanism.

Implicit imagery is more persuasive for gay male than for lesbian imagery, and gay male imagery is more persuasive than lesbian imagery if the ad is for high-involvement products. Generally, the use of implicit homosexual imagery avoids possible negative reactions by heterosexual consumers while targeting homosexual consumers, because it is more congruent with the majority’s schema and expectations. The favorable responses to gay male imagery in combination with high-involvement products confirms the stereotype of high-income and high-spending homosexuals, which is often associated with gay men (e.g., Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015).

In sum, these differential findings shed light on the complex but congruent relationships between the effects of homosexual imagery on one side and consumers, contexts, messages, endorsers, and products on the other side. All told, the congruence among gender-role expectations, individual sexual and gender identities, consumption-related stereotypes, and advertising imagery results in more favorable responses to homosexual advertising imagery.

Managerial Implications

The finding of reverse-negative reactions shows that homosexual portrayals can be used for heterosexual consumers without jeopardizing the persuasive effects of advertising. Hence, marketers can attract heterosexual consumers through sexually diverse advertising portrayals. Conversely, homosexual consumers may be negatively affected by heterosexual imagery, implying unfavorable nontarget market effects. Thus, the general advice is that advertisers should better account for homosexuals’ increased prominence in society, media, and consumer markets, and clearly target and treat them as valuable consumer segments by incorporating corresponding advertising portrayals beyond heteronormative depictions that target mainstream heterosexual consumers.

The results provide a nuanced view on the conditions under which homosexual imagery enhances persuasion and constitutes a promising advertising strategy. First, marketers need to consider the cultural context when using homosexual imagery. In highly masculine countries, advertising using homosexual imagery and, in particular, gay male imagery comes with some costs and risks of potential negative reactions. Portraying lesbian imagery and endorsers, on the other hand, seems to be a viable advertising strategy, except for high-involvement products. Homosexual imagery should be used if it fits the advertised products; marketers are advised to choose homosexual imagery to advertise hedonic products due to the congruent and favorable association of homosexual consumers with hedonistic lifestyles and behaviors of consumption.

Advertising that exclusively targets homosexual consumers should use explicit homosexual imagery. This can be a promising albeit risky strategy in masculine countries because it supports homosexuals in expressing their collective sexual identities in a less-welcoming environment. Marketers should further ponder the choice of homosexual endorsers. While advertisements traditionally depict gay male endorsers, lesbian endorsers are more appropriate to address heterosexual consumers, and lesbian consumers are more persuaded by lesbian imagery too. Therefore, the endorser choice should be adapted to the specific target group; this seems particularly important for the lesbian consumer market, which is considered more fragmented and heterogeneous in terms of preferences for lesbian imagery (e.g., femme versus butch lesbians) than the gay male target market (Braun, Cleff, and Walter Citation2015).

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is common for the use and application of meta-analytic data and techniques. Meta-analysis works with aggregated and generalized findings. Thus, our results provide a broad guideline and a better understanding of the effects of homosexual imagery in advertising but cannot give detailed advice for any particular market segment or any executional decision advertisers may encounter. For instance, while we found differential influences of homosexual imagery across countries, there might well be heterogeneity within a country, and more conservative parts in a country (e.g., the Bible Belt in the United States) will probably react differently toward homosexual imagery in advertising than more liberal parts of the country. In this vein, our meta-analysis, like any other meta-analysis, provides general guidelines and benchmarks that cannot substitute the need for testing creative executions for particular target audiences.

Another limitations is that the data for, and thus the findings from, this meta-analysis are restricted to samples in Western societies that all show strong support of homosexuality. Only one country in the data set (South Korea) currently does not yet allow same-sex marriage. While advertisers are less likely to show homosexual imagery in countries that are less accepting of homosexuality, many advertising campaigns today reach a global audience through online and social media. As a result, both prior research and this meta-analysis reflect the responses of consumers in modern and liberal societies toward homosexual imagery in advertising that is typically created for advertising in these countries, but it ignores the wider effects of such advertising on a global audience. The introductory example noted the company Suitsupply, which launched a campaign with strongly explicit homosexual imagery and which received many negative responses on social media worldwide, but especially in the Middle East, where public opinion is less favorable toward homosexuality (Paauwe Citation2018). Another example is Ikea, which has closed down its lifestyle website in Russia in fear of the country’s legislation about gay propaganda, because the website features photos and interviews about real-life families’ interior décor, including those of same-sex couples (The Guardian Citation2015). In 2018, more than 70 countries still considered homosexuality to be illegal, with 10 of those countries imposing the death penalty for homosexual activity. Future research should try to understand how support for homosexuality influences the reputations of global companies and their advertising campaigns on a worldwide scale.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We applied a power analysis to ensure that we had a sufficient number of effect sizes for a desired power level of 0.8, a given number of predictors, and the anticipated effect size (Faul et al. Citation2009).

REFERENCES

- Aaker, Jennifer L., Anne M. Brumbaugh, and Sonya A. Grier (2000), “Nontarget Markets and Viewer Distinctiveness: The Impact of Target Marketing on Advertising Attitudes,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9 (3), 127–40.

- Åkestam, Nina (2017), “Understanding Advertising Stereotypes: Social and Brand-Related Effects of Stereotyped versus Non-Stereotyped Portrayals in Advertising,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stockholm School of Economics.

- ———, Sara Rosengren, and Micael Dahlen (2017), “Think About It—Can Portrayals of Homosexuality in Advertising Prime Consumer-Perceived Social Connectedness and Empathy?,” European Journal of Marketing, 51 (1), 82–98.

- Angelini, James R., and Samuel D. Bradley (2010), “Homosexual Imagery in Print Advertisements: Attended, Remembered, But Disliked,” Journal of Homosexuality, 57 (4), 485–502.

- Badgett, M. (2001), Money, Myths, and Change: The Economic Lives of Lesbians and Gay Men, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Beals, Kristin P., Letitia Anne Peplau, and Shelly L. Gable (2009), “Stigma Management and Well-Being: The Role of Perceived Social Support, Emotional Processing, and Suppression,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35 (7), 867–79.

- Bernstein, M. (1997), “Celebration and Suppression: The Strategic Uses of Identity by the Lesbian and Gay Movement,” American Journal of Sociology, 103 (3), 531–65.

- Bhat, Subodh, Thomas W. Leigh, and Daniel L. Wardlow (1998), “The Effect of Consumer Prejudices on Ad Processing: Heterosexual Consumers' Responses to Homosexual Imagery in Ads,” Journal of Advertising, 27 (4), 9–28.

- Blashill, A.J., and K.K. Powlishta (2009), “Gay Stereotypes: The Use of Sexual Orientation As a Cue for Gender-Related Attributes,” Sex Roles, 61 (11), 783–93.

- Bond, Bradley J. (2014), “Sex and Sexuality in Entertainment Media Popular with Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents,” Mass Communication and Society, 17 (1), 98–120.

- Braun, Kerstin, Thomas Cleff, and Nadine Walter (2015), “Rich, Lavish, and Trendy. Is Lesbian Consumers’ Fashion Shopping Behaviour Similar to Gays'? A Comparative Study of Lesbian Fashion Consumption Behaviour in Germany,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19 (4), 445–66.

- Capella, Michael L., Charles R. Taylor, and Cynthia Webster (2008), “The Effect of Cigarette Advertising Bans on Consumption: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Advertising, 37 (2), 7–18.

- Chesney, Louis (2017), “LGBT Buying Power Closer to One Trillion Dollars,” Western New York Gay and Lesbian Yellow Pages, July 27, http://wnygaypages.com/lgbt-buying-power/.

- DeLozier, M.W., and J. Rodrigue (1996), “Marketing to the Homosexual (Gay) Market: A Profile and Strategy Implications,” Journal of Homosexuality, 31 (1–2), 203–12.

- De Meulenaer, Sarah, Nathalie Dens, Patrick de Pelsmacker, and Martin Eisend (2018), “How Consumers' Values Influence Responses to Male and Female Gender Role Stereotyping in Advertising,” International Journal of Advertising, 37 (6), 893–913.

- Dinesen, Peter Thisted, and Kim Mannemar Sønderskov (2015), “Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: Evidence from the Micro-Context,” American Sociological Review, 80 (3), 550–73.

- Dotson, Michael J., Eva M. Hyatt, and Lisa Petty Thompson (2009), “Sexual Orientation and Gender Effects of Exposure to Gay- and Lesbian-Themed Fashion Advertisements,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 13 (3), 431–47.

- Eisend, Martin (2017a), “Meta-Analysis in Advertising Research,” Journal of Advertising, 46 (1), 21–35.

- ——— (2017b), “The Third-Person Effect in Advertising: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Advertising, 46 (3), 377–94.

- ———, and Farid Tarrahi (2014), “Meta-Analysis Selection Bias in Marketing Research,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31 (3), 317–26.

- Elias, Troy, and Osei Appiah (2010), “A Tale of Two Social Contexts: Race-Specific Testimonials on Commercial Web Sites,” Journal of Advertising Research, 50 (3), 250–64.

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Axel Buchner, and Albert-Georg Lang (2009), “Statistical Power Analysis Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analysis,” Behavior Research Methods, 41 (4), 1149–60.

- Ghaziani, Amin, Verta Taylor, and Amy Stone (2016), “Cycles of Sameness and Difference in LGBT Social Movements,” Annual Review of Sociology, 42, 165–83.

- Ginder, Whitney, and Sang-Eun Byun (2015), “Past, Present, and Future of Gay and Lesbian Consumer Research: Critical Review of the Quest for the Queer Dollar,” Psychology and Marketing, 32 (8), 821–41.

- Gomillion, Sarah C., and Traci A. Giuliano (2011), “The Influence of Media Role Models on Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity,” Journal of Homosexuality, 58 (3), 330–54.

- Grier, Sonya A., and Anne M. Brumbaugh (1999), “Noticing Cultural Differences: Ad Meanings Created by Target and Non-Target Markets,” Journal of Advertising, 28 (1), 79–93.

- The Guardian (2015), “Ikea Drops Lifestyle Website in Russia Over ‘Gay Propaganda’ Fears,” March 13, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/13/ikea-drops-lifestyle-website-russia-gay-propaganda-fears.

- Herek, Gregory M. (2002), “Gender Gaps in Public Opinion about Lesbians and Gay Men,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 66 (1), 40–66.

- ———, J. Roy Gillis, and Jeanine C. Cogan (2009), “Internalized Stigma among Sexual Minority Adults: Insights from a Social Psychological Perspective,” Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56 (1), 32–43.

- ———, and Kevin A. McLemore (2013), “Sexual Prejudices,” Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–33.

- Hofstede, Geert (1998), Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- ——— (2001), Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ———, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov (2010), Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hunter, John E., and Frank L. Schmidt (2004), Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings, 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Jeong, Se-Hoon, and Yoori Hwang (2016), “Media Multitasking Effects on Cognitive vs. Attitudinal Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis,” Human Communication Research, 42 (4), 599–618.

- Kates, Steven M. (2002), “The Protean Quality of Subcultural Consumption: An Ethnographic Account of Gay Consumers,” Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (3), 383–99.

- Knoll, Johannes, and Jörg Matthes (2017), “The Effectiveness of Celebrity Endorsements: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (1), 55–75.

- Lax, Jeffrey R., Justin H. Phillips, and Alissa F. Stollwerk (2016), “Are Survey Respondents Lying about Their Support for Same-Sex Marriage? Lessons from a List Experiment,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 80 (2), 510–33.

- Lipsey, Mark W., and David T. Wilson (2001), Practical Meta-Analysis, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Oakenfull, Gillian K. (2007), “Effects of Gay Identity, Gender, and Explicitness of Advertising Imagery on Gay Responses to Advertising,” Journal of Homosexuality, 53 (4), 49–69.

- ——— (2013), “Unraveling the Movement from the Marketplace: Lesbian Responses to Gay-Oriented Advertising,” Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 7 (2), 57–71.

- ———, and Timothy B. Greenlee (2004), “The Three Rules of Crossing Over from Gay Media to Mainstream Media Advertising: Lesbians, Lesbians, Lesbians,” Journal of Business Research, 57 (11), 1276–85.

- ———, and ——— (2005), “Queer Eye for a Gay Guy: Using Market-Specific Symbols in Advertising to Attract Gay Consumers without Alienating the Mainstream,” Psychology and Marketing, 22 (5), 421–39.

- ———, Michael S. McCarthy, and Timothy B. Greenlee (2008), “Targeting a Minority without Alienating the Majority: Advertising to Gays and Lesbians in Mainstream Media,” Journal of Advertising Research, 48 (2), 191–98.

- O’Keefe, Daniel J. (2013), “The Relative Persuasiveness of Different Message Types Does Not Vary As a Function of the Persuasive Outcome Assessed: Evidence from 29 Meta-Analyses of 2,062 Effect Sizes for 13 Message Variations,” Communication Yearbook, 37, 221–49.

- Orth, Ulrich R., and Denisa Holancova (2004), “Men's and Women's Responses to Sex Role Portrayals in Advertisements,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21 (1), 77–88.

- Osgood, Charles E., and Percy H. Tannenbaum (1955), “The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change,” Psychological Review, 62 (1), 42–55.

- Paauwe, Christiaan (2018), “Suitsupply verliest duizenden volgers door zoenende mannen,” February 21, https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2018/02/21/suitsupply-verliest-duizenden-volgers-door-zoenende-mannen-a1593132.

- Puntoni, Stefano, Joelle Vanhamme, and Ruben Visscher (2011), “Two Birds and One Stone. Purposeful Polysemy in Minority Targeting and Advertising Evaluations,” Journal of Advertising, 40 (1), 25–41.

- Raudenbush, Stephen W., and Anthony S. Bryk (2002), Hierarchical Linear Models: Application and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Read, Glenna L., Irene I. van Driel, and Robert F. Potter (2018), “Same-Sex Couples in Advertisements: An Investigation of the Role of Implicit Attitudes on Cognitive Processing and Evaluation,” Journal of Advertising, 47 (2), 182–97.

- Reichert, Tom (2001), “'Lesbian Chic' Imagery in Advertising: Interpretations and Insights of Female Same-Sex Eroticism,” Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 23 (2), 9–22.

- Schwartz, M. (2016), “Lesbian’s Representation Evolution in Mainstream Media,” Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 7 (201), published electronically July 7, doi:10.4172/2151-6200.1000201.

- Sethuraman, Raj, Gerard J. Tellis, and Richard A. Briesch (2011), “How Well Does Advertising Work? Generalizations from Meta-Analysis of Brand Advertising Elasticities,” Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (3), 457–71.

- Shen, Fuyuan, Vivia C. Sheer, and Ruobing Li (2015), “Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Advertising, 44 (2), 105–13.

- Snyder, Brendan (2015), “LGBT Advertising: How Brands Are Taking a Stance on Issues,” Think with Google, March, https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/lgbt-advertising-brands-taking-stance-on-issues/.

- Stevenson, Thomas H., and Linda E. Swayne (2013), “Is the Changing Status of African Americans in the B2B Buying Center Reflected in Trade Journal Advertising?,” Journal of Advertising, 40 (4), 101–22.

- Tajfel, Henry, and John C. Turner (1985), “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relations, S. Worchel and W.G. Austin, eds., vol. 2, Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall, 7–24.

- Taylor, Charles R., Ju Yung Lee, and Barbara B. Stern (1995), “Portrayals of African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans in Magazine Advertising,” American Behavioral Scientist, 38 (4), 608–21.

- ———, and Barbara B. Stern (1997), “Asian-Americans: Television Advertising and the 'Model Minority' Stereotype,” Journal of Advertising, 26 (2), 47–61.

- Um, Nan-Hyun (2014), “Does Gay-Themed Advertising Haunt Your Brand?,” International Journal of Advertising, 33 (4), 811–32.

- ——— (2016), “Consumers’ Responses to Implicit and Explicit Gay-Themed Advertising in Gay vs. Mainstream Media,” Journal of Promotion Management, 22 (3), 461–77.

- ———, Kyung-Ok Kim, Eun-Sook Kwon, and David Wilcox (2015), “Symbols or Icons in Gay-Themed Ads: How to Target Gay Audience,” Journal of Marketing Communications, 21 (6), 393–407.

- Yaksich, Michael J. (2008), “Connoisseurs of Consumption: Gay Identities and the Commodification of Knowledgable Spending,” Consumers, Comodities, and Consumption, 9 (2), https://csrn.camden.rutgers.edu/newsletters/9-2/yaksich.htm.

Appendix References

- Aaker, Jennifer L., Anne M. Brumbaugh, and Sonya A. Grier (2000), “Nontarget Markets and Viewer Distinctiveness: The Impact of Target Marketing on Advertising Attitudes,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 9 (3), 127–40.

- Akermanidis, Ereni (2013), “Erasing the Line between Homosexual and Heterosexual Advertising: A Perspective from the Educated Youth Population,” unpublished thesis, University of The Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- ——, and Marike Venter (2014), “Erasing the Line between Homosexual and Heterosexual Advertising: A Perspective from the Educated Youth Population,” Retail and Marketing Review, 10 (1), 50–64.

- Åkestam, Nina (2017), “Understanding Advertising Stereotypes: Social and Brand-Related Effects of Stereotyped versus Non-Stereotyped Portrayals in Advertising,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stockholm School of Economics.

- ——, Sara Rosengren, and Micael Dahlen (2017), “Think About It—Can Portrayals of Homosexuality in Advertising Prime Consumer-Perceived Social Connectedness and Empathy?,” European Journal of Marketing, 51 (1), 82–98.

- Angelini, James R., and Samuel D. Bradley (2010), “Homosexual Imagery in Print Advertisements: Attended, Remembered, But Disliked,” Journal of Homosexuality, 57 (4), 485–502.

- Arias, David (2016), “Effectiveness of Commercials with Same-Sex Affection,” unpublished thesis, San Diego State University.

- Bhat, Subodh, Thomas W. Leigh, and Daniel L. Wardlow (1996), “The Effect of Homosexual Imagery in Advertising on Attitude toward the Ad,” Journal of Homosexuality, 21 (1–2), 161–76.

- ——, ——, and —— (1998), “The Effect of Consumer Prejudices on Ad Processing: Heterosexual Consumers' Responses to Homosexual Imagery in Ads,” Journal of Advertising, 27 (4), 9–28.

- Chae, Yoori, Yumin Kim, and Kim K.P. Johnson (2016), “Fashion Brands and Gay/Lesbian-Inclusive Advertising in the USA,” Fashion, Style, and Popular Culture, 2 (2), 251–67.

- Chinchanachokchai, Sydney (2017), “The Effects of Using Homosexual Presenters in Luxurious Product Advertising,” paper presented at American Academy of Advertising, Boston, MA, March.

- Cunningham, George B., and E. Nicole Melton (2014), “Signals and Cues: LGBT Inclusive Advertising and Consumer Attraction,” Sport Marketing Quarterly, 23 (1), 37–46.

- Descubes, Irena, Tom McNamara, and Douglas Bryson (2018), “Lesbians’ Assessments of Gay Advertising in France: Not Necessarily a Case of ‘La Vie en Rose?’,” Journal of Marketing Management, 34 (7–8), 639–63.

- ——, ——, and Virginie Léger (2014), “Lesbian Perceptions of Gay Advertising in a French Context: A Case of Not Necessarily ‘La Vie en Rose,’” working paper, ESC Rennes School of Business, Rennes, France, June.

- Dotson, Michael J., Eva M. Hyatt, and Lisa Petty Thompson (2009), “Sexual Orientation and Gender Effects of Exposure to Gay- and Lesbian-Themed Fashion Advertisements,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 13 (3), 431–47.

- Hester, Joe Bob, and Rhonda Gibson (2007), “Consumer Responses to Gay-Themed Imagery in Advertising,” Advertising and Society Review, 8 (2), 1–26.

- Hooten, Mary Ann, Kristina Noeva, and Frank Hammonds (2009), “The Effects of Homosexual Imagery in Advertisements on Brand Perception and Purchase Intention,” Social Behavior and Personality, 37 (9), 1231–38.

- Ivory, Adrienne Holz (2007a), “Sexual Orientation: A Peripheral Cue in Advertising?,” unpublished thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- —— (2007b), “Viewer Reponses to Race and Sexual Orientation in Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertisements,” paper presented at International Communication Association Conference, San Francisco, CA, May.

- —— (2019), “Sexual Orientation as a Peripheral Cue in Advertising: Effects of Models’ Sexual Orientation, Argument Strength, and Involvement on Responses to Magazine Ads,” Journal of Homosexuality, 66 (1), 31–59.

- Oakenfull, Gillian K. (2005), “The Effect of Gay Identity, Gender, and Gay Imagery on Gay Consumers’ Attitude towards Advertising,” Advances in Consumer Research, 1, 641–42.

- —— (2007), “Effects of Gay Identity, Gender and Explicitness of Advertising Imagery on Gay Responses to Advertising,” Journal of Homosexuality, 53 (4), 49–69.

- —— (2013), “Unraveling the Movement from the Marketplace: Lesbian Responses to Gay-Oriented Advertising,” Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 7 (2), 57–71.

- ——, and Timothy B. Greenlee (2004), “The Three Rules of Crossing Over from Gay Media to Mainstream Media Advertising: Lesbians, Lesbians, Lesbians,” Journal of Business Research, 57 (11), 1276–85.

- ——, and —— (2005), “Queer Eye for a Gay Guy: Using Market-Specific Symbols in Advertising to Attract Gay Consumers without Alienating the Mainstream,” Psychology and Marketing, 22 (5), 421–39.

- ——, Michael S. McCarthy, and Timothy B. Greenlee (2008), “Targeting a Minority without Alienating the Majority: Advertising to Gays and Lesbians in Mainstream Media,” Journal of Advertising Research, 48 (2), 191–98.

- Parker, Heidi M., and Janet S. Fink (2012), “Arrest Record or Openly Gay: The Impact of Athletes' Personal Lives on Endorser Effectiveness,” Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21 (2), 70–79.

- Pounders, Kathryn, and Amanda Mabry-Flynn (2016), “Consumer Response to Gay and Lesbian Imagery: How Product Type and Stereotypes Affect Consumers’ Perceptions,” Journal of Advertising Research, 54 (5), 426–40.

- Puntoni, Stefano, Joelle Vanhamme, and Ruben Visscher (2011), “Two Birds and One Stone. Purposeful Polysemy in Minority Targeting and Advertising Evaluations,” Journal of Advertising, 40 (1), 25–41.

- Read, Glenna L., Irene I. van Driel, and Robert F. Potter (2018), “Same-Sex Couples in Advertisements: An Investigation of the Role of Implicit Attitudes on Cognitive Processing and Evaluation,” Journal of Advertising, 47 (2), 182–97.

- Rowden, Mandie (2017), “Attitudes Toward Homosexual Imagery in Advertisements: An Examination of Moderating Variables,” unpublished thesis, Middle Tennessee State University.

- Shepherd, Steven, Aaron Kay, Tanya L. Chartrand, and Gavan J. Fitzsimons (2015a), “Cultural Diversity in Advertising and Representing Different Visions of America,” Advances in Consumer Research, 43 (1), 24–25.

- ——, ——, ——, and —— (2015b), “w/o title,” unpublished manuscript.

- Um, Nam-Hyun (2014), “Does Gay-Themed Advertising Haunt Your Brand?,” International Journal of Advertising, 33 (4), 811–32.

- —— (2016), “Consumers' Responses to Implicit and Explicit Gay-Themed Advertising in Gay vs. Mainstream Media,” Journal of Promotion Management, 22 (3), 461–77.

- ——, Jong Min Kim, and Sojung Kim (2016), “Korea out of the Closet: Effects of Gay-Themed Ads of Young Korean Consumers,” Asian Journal of Communication, 26 (3), 240–61.