Abstract

This study reports five Dutch expert history teachers’ approaches to multiperspectivity in lessons on three topics varying in moral sensitivity (i.e., the Dutch Revolt, Slavery, and the Holocaust) and their underlying considerations for addressing subjects’ perspectives in different temporal layers. The lessons were observed and videorecorded, and the teachers were interviewed. Lessons were analyzed using a theoretical framework in which three different temporal layers of perspectives were distinguished, each with its own educational function. Teachers addressed multiple temporal layers and functions of multiperspectivity in almost all of their lessons. However, teachers’ focus on temporal layers and function differed between lessons. Four categories of considerations for or against introducing specific subjects’ perspectives were found: functional, moral, pedagogical, and practical. Moreover, teachers engaged in “normative balancing,” meaning that not all perspectives were perceived as equally valid or politically desirable, showing where multiperspectivity ends.

Over the past 25 years, the term multiperspectivity has gained importance in history education (Bergmann, Citation2000; Grever & Van Boxtel, Citation2014; Meier, Citation1993; Nordgren & Johansson, Citation2015; Stradling, Citation2003). In the context of history education, the notion of multiperspectivity refers to the epistemological idea that history is interpretational and subjective, with multiple coexisting narratives about particular historical events, rather than history being objectively represented by one “closed” narrative. Several researchers have proposed that such an interpretational approach to history education should go beyond relativism by teaching students to judge and compare the validity of different narratives using disciplinary criteria (Seixas, Citation2015; Stoel et al., Citation2017; VanSledright, Citation2011; Wineburg, Citation2001). Proponents of a multiperspectivity approach to history teaching often also have an ideological and normative expectation. They have pointed out that societies become more ethically and culturally diverse which makes an exploration of different perspectives a valuable and necessary way for students to find mutual understanding of different cultures and become responsible democratic citizens (e.g., Barton & Levstik, Citation2004; Grever, Citation2012; Rüsen, Citation1989; Wansink, Akkerman, Vermunt, Haenen, & Wubbels, Citation2017). Currently, this notion of teaching history from multiple perspectives is on the agenda in the educational curricula of many Western nations (Erdmann & Hassberg, Citation2011).

Although multiperspectivity is increasingly emphasized as a desideratum, research has shown that many history teachers struggle with addressing multiple coexisting perspectives. To teach in this way, teachers need a sophisticated epistemic understanding of the nature of history as well as pedagogical expertise on how to achieve such understanding among students (Barton & Levstik, Citation2003; James, Citation2008; Klein, Citation2010, Citation2017; Martell, Citation2013; Wansink, Akkerman, & Wubbels, Citation2016a). Despite the growing plea for multiperspectivity in history education, an operationalization of multiperspectivity still appears to be missing. The aim of the present study is threefold. First, we aim to operationalize multiperspectivity in history education by proposing a theoretical model of temporality and pointing out different educational functions of multiperspectivity. Second, we aim to explore which forms and functions of multiperspectivity teachers address in lessons that vary in topics and in perceived sensitivity. Third, we aim to explain patterns in teaching multiperspectivity by analyzing teachers’ considerations for introducing specific subjects’ perspectives in their lessons and for disregarding others. Focusing on what teachers actually do, and with what considerations, allows us to show not only the practice of teaching multiperspectivity, but also the limitations of such teaching.

A TEMPORAL MODEL OF MULTIPERSPECTIVITY

The word perspective has a Latin root, “perspectus,” meaning “look through” or “perceive.” This original meaning suggests a perspective as inherently relative to the vantage point of a particular viewer (i.e., a subject). Multiperspectivity then, refers to multiple subjects’ views on one particular object; in the case of history education, multiperspectivity typically concerns a historical event or figure. Chapman (Citation2011) has pointed out how multiperspectivity in history is an ambiguous notion. He argued that, on the one hand, when speaking literally on a perceptual level, a subject’s visual perspective plays no role in historical knowing, since the past does not exist anymore and, therefore, cannot be experienced or seen directly by a subject. Chapman (Citation2011) defined a perspective on the past as “a form of short-hand for the ways in which the concepts, questions and practical interests that we bring to study the past shape the conclusions we draw” (p. 96).

Stradling (Citation2003) has defined the characteristics of multiperspectivity as “A way of viewing, and a predisposition to view, historical events, personalities, developments, cultures, and societies from different perspectives through drawing on procedures and processes which are fundamental to history as a discipline” (p. 14). Several authors see the willingness to put oneself in someone else’s shoes as a precondition for teaching multiperspectivity (Barton & Levstik, Citation2003; Wansink, Zuiker, et al., Citation2017). In addition, researchers have noticed that the willingness to take another perspective can reduce when an individual feels emotionally connected with the topic (Barton & McCully, Citation2007; Goldberg, Schwarz, & Porat, Citation2011).

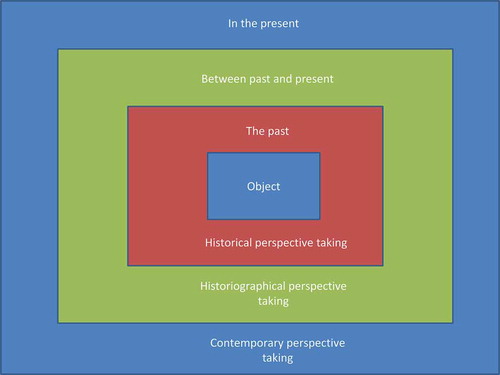

We define multiperspectivity in the context of history and history education as the consideration of multiple subject perspectives on a particular “historical” object (Wansink, Zuiker, Wubbels, Kamman, & Akkerman, Citation2017). This historical object can be a historical event, phenomenon, or figure. To operationalize potential perspectives on the historical object, we propose a temporal framework. With the historical object by definition belonging to the past, potential subjects and their perspectives on the object can exist in three different temporal layers: subjects positioned “in the past” (the time of the event, phenomenon, or figure); subjects positioned “between past and present”; and subjects positioned “in the present.”

With the first temporal layer, in the past, we refer to perspectives of subjects who are contemporaries of the historical object. Primary sources can be used to represent the perspective of the constructor of the source, for example, a letter written by William of Orange (i.e., subject) describing the revolt of the Dutch nobles (i.e., object) against Spain. Multiperspectivity “in the past” refers to parallel or synchronic contemporaneous subjects’ perspectives, and its educational function is typically to teach students that different historical actors may have had different co-existing perspectives on a certain object based on different experiences, beliefs, and ideologies. Several authors have referred to this function in terms of “historical perspective taking,” which is described as understanding the views of people in the past and explaining their beliefs and norms (Endacott & Sturtz, Citation2014; Huijgen, Van Boxtel, Van de Grift, & Holthuis, Citation2017). In this article, we conceptualize historical perspective taking as a cognitive process in which students try to reconstruct an adequate (historical) context to understand and make sense of the subject acting in that specific social and cultural context. Although we acknowledge that historical perspective taking is inescapably presentist and subjective, as during the process of historical perspective taking, individual emotions and the moral relationship of the subject with the historical object always will play a role, we still value the disciplinary rules of engagement as important tools for historical knowledge production. Historical perspective taking shows multiperspectivity only when perspectives of multiple subjects within the same time era are addressed and reflected upon.

The second temporal layer that we distinguish is “between past and present,” referring to perspectives of subjects that did not live simultaneously with the object but that succeeded the object in time and have somehow been concerned with the historical object and its interpretation. Obviously, typical subjects being concerned with the past are historians; yet, they may also be politicians, journalists, or citizens who display their interpretation and view on a historical object because it relates to something in their own time. Multiperspectivity within this temporal layer can concern synchronous subjects situated in the same temporal context (similar to the function of perspective taking “in the past”) as well as to diachronic subjects’ perspectives that succeed each other over time (i.e., in different temporal contexts). An example of focusing on diachronic perspectives would be contrasting a source written by a historian in the 19th century (subject) with a source written by a historian in the 20th century (subject), both of whom are taking a perspective on the Dutch Revolt (object). Although historical perspective taking is addressed in this temporal layer, its educational function is more extensive and complex than perspective taking “in the past.” This is because students must take multiple historical contexts from multiple times into account and students are faced with epistemological questions of the historicity of the historical method (i.e., seeing different potential methods and sources used by subjects to (re)construct the past (Fallace, Citation2007; Iggers, Citation1997; Kosso, Citation2009). Accordingly, we propose that the idiosyncratic function of this temporal layer can be labeled “historiographical perspective taking.”

The third temporal layer we distinguish is “in the present,” referring to those subjects who live in the present and take a contemporary position toward a historical object. Although a distinctive cut between the “past and present” and “contemporary positions or debates” to some degree may be arbitrary, we propose that a cut-off is meaningful for seeing its different educational functions; discussing a recent article of a journalist might serve a different goal for teachers than discussing an article written in the 19th century in terms of showing the significance and constructedness of history in the present for students. In the temporal layer “in the present,” on top of any contemporaries (e.g., current politicians, historians, journalists, or citizens somehow concerned with the object), two distinctive (groups of) subjects are the teacher and the students. The specific educational function of addressing contemporary perspectives is informed reflexivity, that is, the realization that perspectives are personal and that teachers and students themselves are consumers of history, critically or uncritically accepting the constructions presented by others or even making their own constructions of the past (Jonker, Citation2012; Weinstock, Kienhues, Feucht, & Ryan, Citation2017). The function of a teacher explicating one’s own perspective makes clear that a teacher does not live in a vacuum but that he or she is also an interpreter influenced by a specific social and cultural context. The educational function of asking students to take a perspective on a historical object is that it teaches them to construe critically, informed by disciplinary criteria, their perspective on a specific historical object. This function resembles what Rüsen (Citation1989) has named the genetic competence, as during this construction process students should be able to combine and integrate “historical perspective taking” as well as “historiographical perspective taking” to reflect on their own temporal positioning, being actors in the continuous process of historical meaning making. In , depicting our theoretical model, each rectangle refers to the temporal layer in which the subject is positioned and which function is activated in that temporal layer.

TEACHING MULTIPERSPECTIVITY

In several Western nations, the notion that history should be approached from multiple perspectives has become part of the history curricula. In Europe, the term multiperspectivity is used by the Council of Europe (Citation2011), for example, in their recommendation for history teaching in European countries. The Council of Europe (Citation2011) writes that history teaching should contribute to: “the development of a multiple-perspective approach in the analysis of history, especially the history of the relationships between cultures” (p. 3). In addition, curricula of several Western countries refer to different aspects of addressing multiperspectivity. For example, according the Gymnasium curriculum in Niedersachsen (Germany), students must learn that “multiperspectivity at the level of the historical actors, means that the location-boundness of thought and action leads to a limitation of perception” (Niedersächsisches Kulturministerium, Citation2015, p. 15). In England, students at the age of 16–19 are to be taught to “comprehend, analyse, and evaluate how the past has been interpreted and represented in different ways, for example in historians’ debates” (Office for Standards in Qualifications, Citation2011, p. 5). In the Netherlands, students should be able to explain “how people judge and give meaning to the past and how this changed over time and can differ by group and individual” (Board of Examinations, Citation2013, p. 13). In the United States, the College, Career, and Civic Life Framework for social studies standards (National Council for the Social Studies, Citation2013) explicitly states that students should learn about the interpretive nature of history, as “even if they are eyewitnesses, people construct different accounts of the same event, which are shaped by their perspectives” (p. 47).

Despite the increasing emphasis on multiperspectivity in different curricula, research has shown that teachers often find it difficult to address different perspectives and focus on interpretations and evaluations of these perspectives (Barton & Levstik, Citation2003; Bickmore & Parker, Citation2014; Martell, Citation2013). Research also has shown various factors stimulating or constraining a multiperspectivity approach. To start teaching history from multiple perspectives a history teacher requires pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). Shulman (Citation1987), who introduced this term, referred to PCK as “subject matter knowledge for teaching” (p. 9). Three important areas of expertise that need to be integrated to teach history from multiple perspectives are classroom management expertise, content knowledge of existing perspectives, and pedagogical expertise. When lacking these types of expertise, teachers tend to focus more on one perspective represented as a “closed narrative,” partly because it gives certainty to the teacher in teaching practice (James, Citation2008). Besides expertise, the work and learning environment in which teachers function impacts their pedagogies (Flores & Day, Citation2006; Opfer & Pedder, Citation2011). For example, research has shown that teachers give more attention to different perspectives when students’ cognitive levels are high (Wansink et al., Citation2016a). Barton and Levstik (Citation2008) pointed out that teachers focus solely on historical facts when they experience time pressure or feel constrained by the history curriculum. Moreover, teachers can rely heavily on the textbook, which scholars do not typically associate with multiperspectivity (James, Citation2008; Wineburg, Citation2001).

In addition, previous research shows that the practice of teaching interpretational history is topic dependent (Evans, Avery, & Pederson, Citation1999; Wansink, Akkerman, & Wubbels, Citation2016b). According to teachers, a topic is more applicable for focusing on multiperspectivity when the teacher has affinity with and knowledge about the topic, when teaching materials are available addressing different perspectives, and when the topic is included in the (formal) curriculum so that they have enough time to address it in-depth. In addition, teachers should be able to deconstruct the topic and perceive the topic as not too abstract for students.

Finally, earlier research has shown that the moral sensitivity of a topic can influence teachers’ practices (Barton & McCully, Citation2012; Evans et al., Citation1999; King, Citation2009; Salmons, Citation2003). Sheppard (Citation2010) described three features to identify a sensitive historical topic: the topic is often a traumatic event; there is some form of identification between those who study history and those who are represented; and there is a moral response to the topic. Based upon the research of Lorenz (Citation1995) and Goldberg (Citation2013, Citation2017; Goldberg et al., Citation2011), we introduced in a previous study the metaphor of “hot” and “cold” history (Wansink et al., Citation2016b), which refers to history in which parties still have a stake because groups and individuals are morally attached to the historical narratives of this part of their past. The study showed that historical topics perceived as “cold history” (i.e., there was little identification between teacher or student, and those who were represented in the past, thus not evoking a moral response) were perceived by history teachers as applicable for addressing multiperspectivity. In contrast, topics perceived as “hot history” (i.e., traumatic events evoking a moral response and certain degree of identification), were perceived as less or not applicable. In line with previous research, we found how, for example, the Holocaust was deemed too “hot” for several teachers for discussing different perspectives (Borries, Citation2017; Kinloch, Citation1998; Salmons, Citation2003). For moral reasons and fear of relativism most teachers, therefore, chose to present only one undisputable perspective about the Holocaust. It is important to realize that what counts as “hot history” is bound in time, place, and culture; in other words, what is perceived as sensitive history will vary in different educational settings and depends on the teachers’ identity (Goldberg & Savenije, Citation2018).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Whereas some knowledge about the various factors stimulating or constraining a multiperspectivity approach to history teaching is available, little insight exists as to how multiperspectivity can be, and is, addressed in history teachers’ actual practices. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by an empirical investigation into teaching practices and teachers’ considerations, using the presented temporal framework of multiperspectivity and with the following research questions:

What temporal layers and sequences between subjects’ perspectives do expert history teachers address in deliberately designed lessons from a multiperspectivity approach on three different topics?

What considerations for or against introducing specific subjects’ perspectives do expert history teachers have?

METHODS

Participants

To answer the research questions, we purposefully selected (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, Citation2007) five history teachers from a subset of a larger pool of teachers (n = 15). These 15 teachers had participated in a previous study (Wansink et al., Citation2016a) and had been nominated by history teacher educators from five university-based teacher education institutes as being experts in history teaching. In addition to the nomination, the teachers had to meet four criteria to be included in this study. First, they had to actively teach history in higher secondary education (general and pre-university), as the Dutch curriculum for this level of education aims at teaching history from multiple perspectives. Second, we included teachers with at least 10 years of experience (Chase & Simon, Citation1973) to avoid interference of classroom management problems or limited pedagogical expertise. Third, the teachers had to be willing to teach about three topics from a multiperspectivity approach (i.e., Dutch Revolt, Slavery, and the Holocaust) in senior secondary education during the 2015–2016 school year. Therefore, it was important that the selected teachers all had the goal to teach history in such a manner that their pupils were able to develop the epistemological insight that historical narratives are subjective interpretations, made in their own cultural contexts (i.e., that multiple perspectives are possible), yet that historical interpretations can be evaluated based on disciplinary criteria. From the participant pool of a previous study investigating history teachers’ beliefs about interpretational history teaching (Wansink et al., Citation2016b), we could select teachers that adhered to this position and considered it to be a relevant insight for pupils in history education. Finally, seven teachers met all criteria, of which five were willing to participate in this study. shows that the participants were three males and two females with teaching experience ranging from 11 to 26 years. All teachers were White and had been born in the Netherlands.

Table 1. Participants’ Demographics

Design Procedure, Instruments, and Data Collection

The teachers were requested to design a lesson from a multiperspectivity approach to history teaching on three given topics (i.e., the Dutch Revolt,Footnote1 Slavery,Footnote2 and the HolocaustFootnote3). We deliberately chose topics that varied in moral sensitivity and distance in time (Klein, Citation2017), but gave no further directions for, or restrictions to, which historical objects or subject perspectives teachers should address. The choice of topics was based on a previous study in which we asked history teachers in the Netherlands to list topics they found applicable for teaching multiperspectivity (Wansink et al., Citation2016b). The findings of this study showed that the teachers found the Dutch Revolt very applicable (i.e., cold topic) and that the topics of Slavery (i.e., medium hot topic) and the Holocaust (i.e., hot topic) were perceived as less applicable. Therefore, these topics were likely to elicit diverse approaches and considerations regarding multiperspectivity.

Dutch secondary education has three tracks: lower secondary pre-vocational education (four years), general secondary education (five years) and pre-university secondary education (six years). The three topics are part of the official Dutch upper secondary education history curriculum (i.e., upper general secondary education and upper pre-university secondary education, age range 15 to 18 years). Depending on the regular school curriculum, the topics could be taught by the teachers at different moments throughout the school year and to different student cohorts. shows an overview of the classes and demographic characteristics. Dylan and Ruby taught all three lessons to the same classes. Bruce and Kate taught two lessons to the same classes and one to another class. Luke taught all three lessons to different classes. Most lessons were taught to pre-university students. Ruby taught all three lessons to general secondary education pupils. Moreover, she taught in a multicultural class in which most students were second-generation students with non-Western migration backgrounds (i.e., parents mainly coming from Morocco and Turkey). The classes of Luke, Dylan, Bruce, and Kate consisted predominantly of White students with parents with no migration background. Only Bruce’s class (general secondary education, year four) in which he taught about slavery was a multicultural class.

Table 2. Overview of Classes

All teachers gave active consent for filming their lessons. Moreover, for each class that participated in this study the teacher asked students to give active consent for the video recordings. Also, parents were informed and asked to return a signed form only if they did not want their child to participate. The first author attended and videotaped all lessons, collected lesson materials (e.g., PowerPoint presentations, printed assignments, historical sources, etc.), and afterward immediately conducted a semi-structured interview to elicit teachers’ considerations for designing the lesson and to reflect on the given lesson. In order not to influence the teachers’ lessons designs and answers during the interviews, the teachers were not knowledgeable of our conceptual temporal model of multiperspectitivy. The interviews contained questions such as: “What were your lessons goals in relation to multiperspectivity?” and “Did you experience any tensions or dilemmas in designing a lesson about multiperspectivity in relation to this topic?” The questions aimed at eliciting teachers’ learning goals, pedagogies, important moments in relation to multiperspectivity during the lesson, and moral tensions regarding teaching about the topic and/or multiperspectivity. The complete interview guide can be found in Appendix A. Interviews were audiotaped. All audio and video recordings of the 15 lessons and 15 interviews were transcribed.

Analysis

To answer the first question regarding temporal layers (i.e., in the past, between past and present, in the present) and sequences between subject perspectives the teachers addressed, we first identified relevant “units of meaning” in the lesson transcripts (Boeije, Citation2010; Chi, Citation1997). In this study, units of meaning existed of text fragments from the transcripts of varying length in which a subject’s perspective was introduced. Following the conceptualization described in the introduction, a perspective consists of a subject’s “view” of a (historical) object. Additional lesson materials (primary and secondary sources) were also coded when the material represented a specific subject’s perspective. Our coding scheme consisted of three categories corresponding to the three temporal layers. The first category consisted of subjects that lived during the same time as the historical object (i.e., in the past); the second category consisted of subjects succeeding the time of the historical object, yet who are not related to a present discussion (i.e., between past and present), and the third category consisted of subjects that were introduced in the words of the teachers as subjects that take a perspective in a contemporary debate about the object (i.e., in the present). These subjects included the students and the teachers. Students were coded as subjects taking a perspective only when they were explicitly instructed by the teacher to think about and/or to formulate their perspective on a historical object. In all cases we coded the group of students as a single subject, albeit a teacher could ask multiple students to take perspective. We coded the teacher as a subject taking a perspective only when the teacher explicitly mentioned his or her own perspective. The first author distinguished, over all lessons, 146 unique subject perspectives and 204 sequential transitions between subjects (i.e., the same subjects’ perspective can recur in a lesson). The first and third author both independently coded the temporal layer in which the subjects (n = 204) were situated. We checked interrater reliability, resulting in an un-weighted Cohen’s kappa of .74.

To answer the second research question about considerations for or against specific subject perspectives, we first identified relevant “units of meaning” (Chi, Citation1997). In this study these units concerned text fragments from the interview transcriptions containing a consideration, which could be a reason or explanation as to why a specific subject was or was not introduced in the lesson. We used the functions of the different temporal layers (i.e., historical perspective taking, historiographical perspective taking, and contemporary perspective taking) and criteria for or against the applicability of historical topic reported by Wansink et al. (Citation2016b) (i.e., knowledge, affinity, constructedness, deconstructability, abstractedness, sensitivity, materials, inclusion in the history curriculum), as sensitizing concepts. After identifying the considerations, we used a procedure of open coding guided by our sensitising concepts. Our coding procedure consisted of four steps. First, the first and third author independently coded all considerations, being “for” or “against” introducing a specific perspective, resulting in an un-weighted Cohen’s kappa of .97. Second, they both coded if the consideration referred to none or to one of the three temporal layers (i.e., in the past, between past and present, in the present, neutral), resulting in an un-weighted Cohen’s kappa of .76. Third, through a process of open and axial coding (Charmaz, Citation2006), the first author distinguished four categories of considerations, which are functional, pedagogical, practical, or moral. A consideration was coded as functional when a teacher mentioned the educational function of perspective taking as a reason to include or exclude a specific perspective. The code “pedagogical” was ascribed when a teacher, for example, mentioned the degree of difficulty of a certain perspective as a consideration. Practical considerations consisted of reasons related to time constraints, the national curriculum, or the availability of source material. We coded a consideration as moral when the teacher mentioned the perspective to be sensitive or (un)ethical as a reason for it to be included or excluded from the lesson. We checked the inter-rater reliability of these four categories after independent coding by the first and third author resulting in a satisfactory unweighted Cohen’s kappa of .79.

FINDINGS

Four Examples of Lessons Focusing on Different Functions of Temporal Multiperspectivity

Before turning to the results of our coding exercises, we first describe four lessons to illustrate how multiperspectivity can be taught and to show the variety of possible approaches. In the remainder of the section, we refer to these lessons as specific illustrations of the functions of multiperspectivity that teachers aimed at when introducing specific subject perspectives and instructions. For reasons of clarification, all four lesson examples are about the Holocaust, yet they vary in temporal focus, respectively focusing mainly on perspectives “in the past” (historical perspective taking), perspectives “between past and present” (historiographical perspective taking), perspectives in “the present” (contemporary perspective taking), and finally, perspectives from multiple temporal layers.

Lesson example one: Mainly focusing on “the past” and historical perspective taking

For this lesson, teacher Dylan developed a role-play in which students had to put themselves into the shoes of different fictional historical figures who lived directly after World War II. Dylan simultaneously introduced five contrasting subject perspectives (i.e., talk-show host, the opportunist, a fanatic Nazi, a resistance fighter, and an Auschwitz survivor). Dylan instructed the students to reconstruct a (historical) context around their historical figure and to “completely abandon their own value systems” and to “imagine” their figure. Then, the students were given time to reconstruct the historical figures’ lives by thinking about their social environment, work, beliefs, etc. In small groups, the students practiced how they would react to different questions as “their historical figure.” Finally, the whole class participated in the role-play in which one pupil played the role of talk-show host and asked the other students questions about their perspectives (representing a historical figure). For example, the talk-show host asked an “opportunist” why he was not in the resistance. The student answered, as his historical figure, that he was afraid of losing his job (i.e., historical perspective taking). After the role-play during the last minutes of the lesson, Dylan showed a short television fragment that had been broadcast on a Dutch news channel the day before in which, after the commission of a crime, some Dutch politicians plead for ethnical registration. Then, Dylan instructed the students to formulate their opinion on this present debate, thereby referring to the notion that the Holocaust started with ethnical registration. A student, for example, answered that he was afraid that ethnical registration could lead to negative generalizations of populations (i.e., contemporary perspective taking).

Lesson example two: Mainly focusing on “between past and present” and historiographical perspective taking

Teacher Bruce started his lesson by handing his students abstracts of four different books (written in different years) about the Holocaust. The students were given time to read all the abstracts. Bruce started to discuss the first book, De Meelstreep, written in 2001 about the rather cold reception of Jews after World War II in the Netherlands (Bossenbroek, Citation2001). An exemplary question Bruce asked his students was: “What does this [book] say about the way the Holocaust was perceived? And what are the differences between the year 1945 and the year 2000?” A student responded that the Holocaust was long before the year 2000, which means that society could look at the emotional pain instead of just the material damage because the latter had been repaired (i.e., historiographical perspective taking). Then, Bruce discussed a book about the Dutch destruction of the Jews, written in 1965 by Jacques Presser, a Dutch Jewish professor. Bruce outlined the impact of the book on Dutch society, thereby asking the students to reconstruct the cultural context of the 1960s. Afterward, he discussed the book Hitler’s Willing Executioners, written by Daniel Goldhagen in 1996. He instructed the students to contrast Goldhagen’s (Citation1996) perspective on the Holocaust with that of Presser (Citation1965). A student, for example, answered that Goldhagen’s perspective was much less dramatic. At the end of the lesson Bruce critically discussed the book, The Holocaust Industry, written by Norman Finkelstein (Citation2000). Bruce pointed out that, for Finkelstein, the Holocaust had become something sacrosanct and that cynical organizations were using this status to earn money. Bruce ended his lesson referring to the different books with the words: “You know I am not saying this is the truth. No, these are perspectives.”

Lesson example three: Mainly focusing “in present” and contemporary perspective taking

Teacher Luke started his lesson by explaining the meaning of the word Holocaust and showing a short film in which Hitler gives a speech about the exterminations of Jews. Then, he showed a popular YouTube video from 2010 in which a Holocaust survivor dances with his family in Auschwitz to the song “I Will Survive,” by Gloria Gaynor. Directly after showing the video, Luke asked his students for their reactions by posing questions such as “would you have made this video?” A student, for example, responded: “Yes. First I thought it was disrespectful because they make everything so ridiculous as they are dancing, but later it turns out that they are happy because their grandfather survived and they are celebrating joy” (i.e., contemporary perspective taking). Luke made his own perspective explicit by conveying that he had watched the video with mixed emotions. After the plenary discussion, he showed and discussed several actual comments beneath the YouTube video to show that people can have different and extreme opinions. Then, Luke showed a short video in which the dancer was asked to explain his motives. At the end of the lesson, the students were asked to design interview questions for the maker of the video. It was planned that, in a later lesson, a Skype session would be held with the maker of the video.

Lesson example four: Mixed temporal focus and addressing multiple functions of multiperspectivity

Teacher Kate started her lesson by discussing a newspaper article from the day before in which the following question was asked: “If you could go back in time would you murder this baby [picture of Hitler]?” She pointed out that the general message of the article was the question as to whether there would have been a World War II without Hitler. Next, Kate said that the main goal of the lesson was to investigate who was guilty of the Holocaust. Therefore, she had developed an assignment in which students individually had to decide who was most guilty of the Holocaust (i.e., contemporary perspective taking). In doing so, students had to rank different historical subjects in order of their guilt, such as Hitler, Eichmann, and the entire German population. In the plenary discussion after the assignment, it became clear that the students had different opinions about how to rank the historical subjects. Moreover, many students struggled with the ranking of subjects. For example, several students said it was difficult to decide if the Holocaust was the responsibility of the entire German people (i.e., contemporary perspective taking). Afterward, the students were given three schoolbooks from different time periods, and they had to find out who was guilty of the Holocaust according to the authors of these books (i.e., historiographical perspective taking). At the end of the lesson, Kate asked her students to write a paragraph in the history schoolbook about who, according to them, was guilty for the Holocaust. She said to the pupils: “I invite you to write that paragraph and to make that construction” (i.e., contemporary perspective taking).

Subject Perspectives

The four lessons described previously on the Holocaust vary in relation to the subject perspectives that were introduced in the different temporal layers. In the remainder of this section we discuss , which presents the number of different subject perspectives that teachers have introduced and in which temporal layers these subjects were situated over all 15 lessons. We describe the results per temporal layer by first presenting the lessons in which the teachers mainly addresses a specific temporal layer and, in doing so, a specific function of multiperspectivity. The numbers in the cells represent the amount of different subject perspectives that were addressed in one lesson. See, for example, lesson example two by Bruce, in which he introduced five subject perspectives in the temporal layer between past and present. It should be noted that although a single subject perspective could be mentioned multiple times in a lesson, such repitition is not shown in . Next, we describe in how many lessons subjects in each temporal layer were addressed, including the number of subjects over all lessons and notable differences between teachers or between the topics in addressing subjects within the temporal layer.

Table 3. Number of Different Unique Temporal Positioned Subjects per Lesson

Results per Temporal Layer and Function of Multiperspectivity

In the past

Based on , we found that six lessons (1, 2, 6, 7, 10, and 11) mainly addressed perspectives of subjects positioned “in the past” and, according to our theoretical model, mainly focused on historical perspective taking. A good example is the first lesson vignette in which students had to put themselves in the shoes of a specific historical figure. During his instruction, Dylan introduced many features that we consider important elements of historical perspective taking, such as reconstructing an adequate (historical) context and reflexivity of presentism.

shows that, in total, 74 different subject perspectives were addressed over 14 lessons (i.e., 51% of all addressed perspectives). The most subject perspectives in this temporal layer were addressed by Ruby (n = 30) and the least by Bruce (n = 6). The number of addressed subject perspectives varied considerably per lesson and topic, ranging from a perspective of 1 to 17 subjects. In relation to pedagogy, we found that in most lessons (n = 12) teachers contrasted “synchronic” contemporaneous subjects’ perspectives. Illustrative is lesson example one in which Dylan simultaneously introduced five contrasting subjects’ perspectives situated within the same historical context (e.g., the opportunist, a fanatic Nazi, a resistance fighter, and an Auschwitz survivor).

Between past and present

In relation to the temporal layer “between past and present” we found that three lessons (3, 4, and 13) were oriented mainly to subjects positioned “between past and present” and were subsequently focused mainly on historiographical perspective taking. Illustrative is the second lesson example in which Bruce contrasted four different books on the Holocaust written during different times. Another example is the lesson about the Holocaust from Kate in which the students had to compare and analyze three schoolbooks written in different eras on how the authors of these books wrote about who is guilty of the Holocaust.

shows that, in total, 35 different subjects’ perspectives were addressed in nine lessons (i.e., 24% of all addressed perspectives). Most subjects in this temporal layer were addressed by Ruby (n = 14), and we found that Luke (n = 0) and Dylan (n = 1) positioned almost no subjects in this temporal layer. We observed that within the temporal layer between past and present in six lessons teachers contrasted diachronic subject perspectives, which means that they addressed subject perspectives in different time eras. For example, Ruby addressed subject perspectives situated in the 19th century as well as situated in the early 20th century and discussed how these subjects’ written work on the Dutch Revolt (i.e., 16th century) was influenced by their positions in time and place as well as their religious identity. Again, the number of subject perspectives turns out to differ per lesson and per topic, ranging from one subject to ten.

In the present

In relation to the temporal layer “in the present,” shows that there were two lessons (5 and 8) that mainly focused on addressing subjects in this temporal layer, subsequently focusing mainly on contemporary perspective taking. An example is lesson five in which Luke asked the students multiple times to formulate their own perspective on a recent YouTube video and the comments beneath the video. Another example is the lesson from Bruce about slavery in which he discussed if contemporary descendants of slavery should receive compensation, leading to a heated debate in the class.

shows that, in total, 37 different subjects’ perspectives were addressed divided over 12 lessons (i.e., 25% of all addressed perspectives). In our theoretical framework, we distinguished three different types of subjects that can be positioned in this temporal layer: subjects that participate in a contemporary debate, who could also, however not exclusively, be the students and the teacher. Regarding the first subject type, we found that perspectives of subjects in a contemporary debate were addressed in eight lessons. Three teachers connected their Holocaust lesson with a contemporary debate. For example, Dylan related the Holocaust discussion to a current debate in the Netherlands about whether ethnicities of criminals should be registered after committing a crime. In the second type, students’ own perspectives, we observed how all teachers instructed students to formulate their own perspective, but some more often than others (e.g., Ruby only once, but Kate throughout all three lessons).

Formulating students’ own perspective was most apparent in lessons about the Holocaust and Slavery (i.e., eight out of the ten lessons on these topics). The fourth lesson example in which students had to write a paragraph in their history schoolbook about who, according to them, was guilty of the Holocaust is a good illustration. An overall observation was that teachers were always in charge, never asking students to introduce a certain perspective. Third, shows that in only five lessons (by four teachers), the teacher made his or her own perspective explicit. For example, Ruby, during her lesson about the Holocaust, discussed the ideas of Hannah Arendt. During the lessons she said, “I actually think that Hannah Arendt’s opinion is still standing.” Ruby was explicit about her own perspective in two of her lessons, whereas Bruce was not explicit in any of his lessons. shows that there were also lessons in which teachers did not focus on just one specific temporal layer (9, 12, 14, and 15) and consequently focused on multiple functions of multiperspectivity. Lesson example four, in which Kate frequently switches between contemporary perspective taking and historiographical perspective taking is a good illustration.

Finally, regarding the temporal sequence of subjects’ perspectives, we found that in 14 lessons teachers shifted across temporal layers, which means that in almost all lessons students had to reconstruct multiple and diachronic (i.e., over time) historical contexts. We noticed that in six lessons, students were asked to formulate their own perspective at the end of the lesson, indicating that students had to conclude by combining multiple temporal layers.

Considerations for and Against Introducing Subjects’ Perspectives

In this section, we will first describe the teachers’ considerations for and against introducing subjects’ perspectives per temporal layer. shows how many teachers referred to goals related to that specific function of multiperspectivity and if they had any moral considerations in relation to this temporal layer. Next, we will determine if teachers had any pedagogical or practical considerations that could be related to the temporal layer. Finally, we will present other types of considerations expressed by the teachers that could not be related to a specific temporal layer and were, therefore, categorized as neutral. Because we consider the pedagogical and practical considerations as more general concerns related to all history teaching and not specific to multiperspectivity we did not present them in .

Table 4. Valence of Teacher Considerations in the Categories Functional (i.e., Historical Perspective Taking, Historiographical Perspective Taking, and Contemporary Perspective Taking) and Moral and in the Three Temporal Layers

In the past

When it comes to the temporal layer “in the past,” we found that all teachers except for Bruce referred in the interviews to goals related to the function of historical perspective taking as a reason for introducing perspectives of subjects in the past in one or more of their lessons. In the interview held after the first lesson example, Dylan described that his main goal for this lesson was teaching students to empathize with a certain figure in the past to understand this figure’s choices and teach the students that the figure’s opinions depended on their position in time and place.

In relation to moral considerations, several teachers stated that addressing subjects “in the past” was not morally sensitive for the students. For example, Bruce said about discussing different subjects’ perspectives during the Dutch Revolt: “It is very safe; it is the 16th century.” Also, Dylan said that this topic was not sensitive for his students: “No, it is too far removed from the world of these children.” Concerning the Holocaust, one teacher (Ruby) exposed specific considerations against specific subjects’ perspectives she addressed “in the past.” Ruby deliberately disregarded the perspectives of the Jews framed as victims of the Holocaust. She said she did not want to focus on the victimhood of the Jews (i.e., subjects) stating that a few of her Islamic pupils might have little empathy for the Jews due to downplay of the Holocaust at home. She certainly did not want to avoid the Holocaust, but she wanted to focus on the perspectives of the perpetrators with the goal to discuss the historical question as to what extent the Holocaust was unique.

Finally, we discerned two more general pedagogical considerations that the teachers related to this temporal layer. Ruby explicitly used primary historical sources (representing a specific subject in the past) to motivate students to participate in her lesson, and Dylan said that specific primary sources could be too abstract for students.

Between past and present

For the temporal layer “between past and present,” we found that all teachers except for Dylan referred to goals, which we coded as historiographical perspective taking, as a reason for introducing subject perspectives “between past and present.” Illustrative is Bruce (lesson example two) who said during the interview, “What I wanted to show is primarily the changing meaning of historical events over time. How do different generations deal with the past, what does the past mean for them and what reinterpretation of the past occurs consequently.” Another teacher who referred to what we consider historiographical perspective taking was Luke who said in the interview after his lesson about slavery, “My goal was to make clear that the term slave, or slavery, is of all times. And there are several ways to look at slavery.” In relation to moral considerations, Bruce said that there was one Jewish girl in his classroom for whom approaching the Holocaust from a historiographical perspective might be very sensitive (lesson example two). However, instead of disregarding more controversial subject perspectives (i.e., the perspective of Finkelstein) he spoke with her before the lesson and told her about the aim of the lesson. Bruce said during the interview that his aim was teaching the students how the Holocaust is perceived differently over time and in various contexts, as well as that these different constructions of Holocaust can be evaluated and critiqued (i.e., historiographical perspective taking).

Finally, two teachers exposed specific pedagogical considerations in relation to this temporal layer. Bruce said that teaching about historiography is mostly applicable for students with higher cognitive levels because historiography can be very abstract for students. Ruby said it is difficult to address subjects’ perspectives in multiple historical contexts during a lesson because students often lack contextual historical knowledge. She said, “And I hear myself talk while I realize they can’t follow me because they don’t know the (historical) context of that time.”

In the present

In relation to the temporal layer “the present,” we found that all teachers, divided over 13 interviews, referred to the function of contemporary perspective taking as a positive consideration for addressing present perspectives. An illustrative example is Luke who said, in relation to his lesson about the Holocaust (lesson example three), that his main goal was to have students think for themselves and to form their own perspective on how to remember the Holocaust (i.e., contemporary perspective taking). Kate said during the interview that she wanted her students to become critical toward their own textbook (lesson example four). She said, “The schoolbook gives a certain perspective and what do you [i.e., students] think of that?” Moreover, she said that her students had to write their own paragraph about the Holocaust to understand that value free writing is impossible.

During his lesson on slavery, Luke explicitly warned for presentism by pointing out that slavery was perceived differently in the past than in the present, saying, “You cannot judge slavery from a present perspective.” However, he also indicated during the interview that he considers this idea to be very complex for his students. Although all teachers addressed contemporary perspective taking by asking the students to ultimately form their own perspective, when doing so little attention was given to the particular contexts in which the pupils themselves lived, which could help explain the differences in the class.

A central contemporary perspective is the one of the teacher. shows that, in the interviews, only Kate mentioned the importance of the teacher being explicit about his or her perspective in the classroom. She said being explicit is important, “To show that teachers also have a perspective, that teachers can be one-sided and that you can also be critical about your teacher.” In contrast to Kate, three other teachers had explicit considerations against addressing their own perspective. These teachers mentioned in the interviews that they did not want to give their own perspective in the classroom, as they did not want to impose their opinions on the students; they argued that doing so could constrain students in becoming critical and autonomous thinkers themselves. However, the teachers contradicted themselves at points during the interviews. For example, Luke said in relation to the lesson about the Holocaust, “I do not want to impose my opinion on students.” He, however, also stated that it is not good to promote anti-Semitism but later in the interview contradicted himself by saying, “I wanted them to discover themselves that there are different views. Whether these views are right or wrong, is something I do not discuss.”

Also, Ruby struggled with the extent to which she would be explicit about her own perspective. On the one hand, she did not want to impose her values as she wanted the students to become autonomous thinkers. On the other hand, she said that her lessons aimed at educating students “who do not follow the populists.” Moreover, Ruby struggled with how to deal with the students who she thought had negative opinions about Jews. Consequently, she had strict moral norms about which perspectives were tolerated in the classroom. Ruby said in relation to the few pupils who wanted to trivialize the Holocaust: “I said to them (i.e., students): I am sorry, but this is not funny, this is not a topic to laugh about. I said that your own opinion does not count for this topic.”

We found that three teachers had explicit moral considerations against addressing specific perspectives concerning the Holocaust, which were all related to the present. These teachers deliberately did not address the perspective of Holocaust denial in their lessons. For example, Kate said, “Because there is still such a thing as absolute evil, you have to say: I will have nothing to do with this absolute form of evil.”

It should be noted that none of the teachers disregarded specific subject perspectives in relation to their lessons about slavery or the Dutch Revolt. Still, some teachers made comments about the moral sensitivity of slavery. Bruce said that, for his students, the history of slavery was sensitive, but he knew his pupils so well that he could manage to discuss conflicting perspectives in his classroom. Ruby said that for her students the topic was not sensitive, but for her personally it was. For example, she struggled with how to deal with the primary sources. She said, “Before you know it you are talking without any respect. You must not use the word nigger, but you see it in all sources, so before you know it you’re talking about niggers.”

Pedagogical and practical considerations

Finally, besides considerations that could be related to a specific temporal layer, teachers also had more general pedagogical and practical considerations for or against addressing a specific subject perspective. First, time was an issue that was frequently mentioned as constraining the teachers in the introduction of multiple perspectives (n = 10). Moreover, the teachers also mentioned the importance of the availability of historical sources (n = 8), such as primary sources, and their affinity or lack thereof with a specific subject (n = 3) as a consideration for or against addressing a subject in the lesson.

DISCUSSION

In the Netherlands, as well as in several other Western countries, teaching history from multiple perspectives has become an obligatory part of the history curriculum. Despite this shift in expectations for history education, little is known about the way teachers address multiperspectivity in their teaching practices and what their underlying considerations are. To investigate teachers’ practices empirically we have conceptualized multiperspectivity in a temporal manner, proposing that subjects’ perspectives may concern three different temporal layers (i.e., in the past, between past and present, in the present), each with a distinctive educational function of multiperspectivity, respectively: historical perspective taking, historiographical perspective taking, and contemporary perspective taking.

When considering which subjects’ perspectives per temporal layer were addressed in the lessons, we found noteworthy variation. To start, one third of the lessons mainly focused on perspectives in the past, although the number of perspectives differed across lessons.

During the interviews that were held after these specific lessons, the teachers explicitly mentioned goals related to the function of historical perspective taking as described in our theoretical framework. This overall attention for “the past” might be explained by the fact that this temporal layer can be considered as history teachers’ main goal, in line with the Dutch history education program (Board of Examinations, Citation2013).

In contrast to the dominant focus on perspectives in the past, we found only a few lessons focusing mainly on perspectives “between past and present,” emphasizing historiographical perspective taking. It is with regard to this temporal layer that we see the largest differences between teachers, with three teachers incorporating this temporal layer in almost all of their lessons and two teachers almost entirely disregarding it. An explanation for these differences between teachers could be that this temporal layer is not in the forefront of all teachers’ minds, as the Dutch curriculum provides little or no guidance to which subjects’ perspectives can be addressed in this temporal layer (Board of Examinations, Citation2013). Moreover, in line with literature, we found that historiographical perspective taking is argued to be very abstract for students, with students often lacking the knowledge to reconstruct multiple historical contexts (Fallace, Citation2007; Fallace & Neem, Citation2005; Yilmaz, Citation2008).

Concerning the temporal layer “in the present,” we found that in two-thirds of the lessons, teachers asked their students to formulate their own perspective. Moreover, in almost all interviews, teachers mentioned lesson goals that were related to contemporary perspective taking, emphasizing the aim of teaching students to be critical and to formulate a perspective themselves. According to the teachers in this study, given this frequent emphasis, this function of multiperspectivity seems to be the most prominent. We found that in six of the lessons, the pupils were instructed to formulate their own perspective at the end of the lesson, indicating that pupils had to wrap up and integrate multiple temporal layers into their own perspectives. Based upon our theoretical model and Rüsen’s (Citation1989) concept of the genetic competence, one could argue that only in one-third of the lessons an elaborate form of multiperspectivity was achieved when all three functions of multiperspectivity were integrated. However, it is questionable if it is realistic and desirable to address all temporal layers in one lesson because all teachers mentioned how they struggled with the limited time in their lessons.

In relation to the moral limits of multiperspectivity, we observed that none of the teachers asked the pupils directly to introduce a specific subject’s perspective in the lesson, meaning that the teachers functioned as “gatekeepers,” making the decisions as to which subjects’ perspectives were and were not addressed in the lesson (Thornton, Citation1991). This finding is particularly important because the teachers explicated their own perspectives in only five of the lessons and, therefore, consciously or unconsciously enacted invisible censorship of their students by imposing specific “hidden” representations of the past (Bourdieu, Citation2001). Three teachers pointed out they were deliberately not explicit about their own perspective and, as such, strove for a “value-neutral” position. However, as indicated by several scholars, it is impossible to be value-free, as teachers’ values are reflected in almost everything—in the curricular content, the way they dress, the language they use, and how they address children (Bartolomé, Citation2008; Pantić & Wubbels, Citation2012). We found, in relation to teaching history from a multiperpsecitivty approach, that these three teachers struggled with incorporating their own values in their lessons, as these teachers also noticed having normative goals themselves or limiting the perspectives that were tolerated in the classroom.

Based on Veugelers and De Kat (Citation2003) and Van Nieuwenhuyse and Wils (Citation2012), we propose that these teachers engaged in what we refer to here as “normative balancing” between transferring values (i.e., imposing your own perspective) and value communication, (i.e., discussing different perspectives). Regarding this “normative balancing,” a more general conclusion is that when teachers’ own values were not at stake, because the teachers seemingly did not feel emotionally concerned with the topic, the teachers could focus on discussing contrasting subjects’ perspectives. We found, for example, that teachers did not have any moral considerations against introducing specific subjects’ perspectives in relation the Dutch Revolt and slavery, meaning that these topics were perceived as rather cold historical topics. Whereas this finding is not so surprising for the Dutch Revolt given its distance in time, we were more surprised that teachers did not identify with slavery. Explanations could be demographic characteristics of the classes, as students with Caribbean backgrounds (i.e., possible descendants of slaves) were almost absent in all the classes, as well the significance that is attributed to both historic events in Dutch society since more attention is given to World War II than to slavery (Savenije, Citation2014).

In line with previous research we found that the teachers identified themselves morally with the victims of the Holocaust and perceived this topic as hot history, which caused them to focus more on transferring “absolute values” (Borries, Citation2017; Salmons, Citation2003). Ruby particularly struggled with how to incorporate her own moral standards in her lessons because a few of her students rejected the narrative of Jewish victimhood during the Holocaust. Previous research in the Netherlands has shown that Islamic students with a migration background tend to think negatively about Jews because they easily identify themselves with the Palestinians in the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict and may intermingle this conflict with the Holocaust (Van Wonderen & Wagenaar, Citation2015). Ruby, on the one hand, wanted to be neutral and discuss the different perspectives as open as possible, but she also wanted to set moral boundaries by not addressing Holocaust denial. In terms of Hess and McAvoy (Citation2014), the question whether the Holocaust actually happened can be perceived as a settled issue, which means there are no alternative rational viewpoints and, therefore, it is not a suitable topic for discussing multiple perspectives. Still, we think that in the face of fake news and ethical relativism, when Holocaust denial occurs in the classroom it should be addressed by evaluating the arguments based on disciplinary criteria, thereby showing that Holocaust denial is irrational.

In addition, we observed that striving for a value-free position also could hinder the teachers to deconstruct on which criteria historical actors grounded their knowledge and moral beliefs. For example, Dylan asked students to step into the shoes of a fanatic Nazi (lesson example one) but did not discuss the underlying morality of this perspective. In addition to that this activity can create an unsafe environment for those students who identify with the historical topic, we believe that historical perspective taking does not mean that students must agree morally with the actions of historical actors. Moreover, previous research indicates that the activity as introduced by Dylan, with fictional figures in which students must imagine themselves, can enhance a historical presentist imagination, especially when students lack enough information or time to familiarize themselves with the figure (Rantala, Manninen, & van den Berg, Citation2016).

We propose that teachers should enable students to investigate moral perspectives of actual historical subjects by providing them a framework of disciplinary criteria to evaluate and discuss on which underlying values and epistemologies moralities are based (such as religion or ideology). Such a framework also can be used by students to reflect on their own criteria for reliable knowledge and moral judgments in the present. However, to do so, teachers need a defensible theory of historical inquiry; as Levisohn (Citation2010) wrote, “a normative theory that accounts for our best practices while also potentially standing in critique of them” (p. 4). In line with many other researchers, we propose that historical knowledge should not be represented as factual or as fictional, but from an intersubjective viewpoint (i.e., an open narrative) based upon (historical) evidence that can be questioned using rationality and disciplinary criteria (Van Drie & Van Boxtel, Citation2008; VanSledright, Citation2011; Wineburg, Citation2001).

This study has several implications. First, we propose that thinking about multiperspectivity in a temporal manner and the functions that are related to temporal layers can become part of teacher education and teacher training programs in order for teachers to realize that by positioning subjects in different temporal layers, different functions of multiperspectivity are activated. Moreover, teachers might be helped by seeing examples of lessons in which different functions of multiperspectivity are addressed, as not all teachers have time or expertise to develop these lessons. Second, to stimulate historiographical perspective taking, a recommendation for curriculum designers could be to prescribe more often which historiographical subjects should be addressed or provide more guidance on how historiographical subjects can be addressed without making it too abstract or complicated for students. Also, teachers might be stimulated to teach about historiographical perspective taking by providing historiographical training that should be closely connected with their teacher practices (Fallace & Neem, Citation2005; McDiarmid & Vinten-Johansen, Citation2000).

This exploratory study should be seen as a starting point for further investigation. First, to investigate the generalizabilty of the findings, we propose that the results of this study should be contrasted with the results of a study in which regular lessons of history teachers are observed. Second, future research can investigate the impact of addressing multiperspectivity on students and studying students’ cognitive and affective limitations in understanding multiperspectivity. Third, we propose that future research could delve more into teachers’ lessons over longer periods to find out if teachers are consistent or inconsistent in which temporal layers and functions of multiperspectivity they address. Fourth, we advocate for studies on the relationship between the different functions of multiperspectivity and historical topics. Previous research has suggested such a relationship exists (Wansink et al., Citation2016b). Finally, future research could focus on where multiperspectivity “ends” and further investigate the tense relationship between a teacher’s moral values and multiperspectivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks are given to Professor Ed Jonker for providing thorough feedback on several versions of this manuscript.

Notes

1 The Dutch Revolt (1570–1680) refers to the revolt of the northern, largely Protestant Seven Provinces of the Low Countries against the rule of the Roman Catholic King Philip II of Spain. The revolt led to the formation of the independent Dutch Republic, whose first leader was William of Orange (Hart, Citation2014). The Dutch Revolt is considered (by scholars contested) the tale of origin of the Netherlands.

2 Dutch involvement in the transatlantic slave trade covers the period between the late 15th and the mid-19th centuries. The Dutch transatlantic slave trade was mainly in the hands of the West Indian Company. The Netherlands abolished slavery in 1863 (Oostindie, Citation2009). Although the transatlantic slave trade has gradually been accepted as a significant topic in Dutch history, the public discussions about the Dutch involvement in slavery can be emotional and morally judgmental (Klein, Citation2017).

3 The Holocaust has a prominent place in recent Dutch collective memory. As in many other Western countries, the Holocaust particularly functions as a moral reference point (Judt, Citation2006; Rothberg, Citation2009). The Holocaust is part of the official Dutch history curriculum for secondary pre-university education. The matter of how it should be addressed by the teacher is, however, left open. The government did not set any official requirements in relation to how Holocaust education should be taught (Boersema & Schimmel, Citation2008).

REFERENCES

- Bartolomé, L. I. (Ed.). (2008). Ideologies in education: Unmasking the trap of teacher neutrality. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2003). Why don’t more history teachers engage students in interpretation? Social Education, 67, 358–362.

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2008). History. In J. Arthur, C. Hahn, & I. Davies (Eds.), Handbook of education for citizenship and democracy (pp. 355–366). London, UK: Sage.

- Barton, K. C., & McCully, A. (2007). Teaching controversial issues… where controversial issues really matter. Teaching History, 127, 13–19.

- Barton, K. C., & McCully, A. W. (2012). Trying to “see things differently”: Northern Ireland students’ struggle to understand alternative historical perspectives. Theory & Research in Social Education, 40, 371–408. doi:10.1080/00933104.2012.710928

- Bergmann, K. (2000). Multiperspektivität: Geschichte selber denken. Hesse, Gremany: Wochenschau-Verlag.

- Bickmore, K., & Parker, C. (2014). Constructive conflict talk in classrooms: Divergent approaches to addressing divergent perspectives. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42, 291–335. doi:10.1080/00933104.2014.901199

- Board of Examinations. (2013). Geschiedenis HAVO & VWO, syllabus centraal examen 2015 op basis van domein A en B van het examenprogramma [History HAVO and VWO, syllabus national exam 2015, based on domain A and B of the curriculum]. Retrieved from http://www.examenblad.nl

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.

- Boersema, J. R., & Schimmel, N. (2008). Challenging Dutch Holocaust education: Towards a curriculum based on moral choices and empathetic capacity. Ethics and Education, 3, 57–74. doi:10.1080/17449640802033254

- Borries, B. V. (2017). Learning and teaching about the Shoah: Retrospect and prospect. Holocaust Studies, 23, 425–440. doi:10.1080/17504902.2017.1298348

- Bossenbroek, M. (2001). De meelstreep. Terugkeer en opvang na de Tweede Wereldoorlog [De meelstreep. Return and reception after the Second World War]. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Bakker.

- Bourdieu, P. (2001). Television. European Review, 9, 245–256. doi:10.1017/S1062798701000230

- Chapman, A. (2011). Taking the perspective of the other seriously? Understanding historical argument. Educar Em Revista, 42, 95–106. doi:10.1590/S0104-40602011000500007

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.

- Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 55–81. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(73)90004-2

- Chi, M. T. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6, 271–315. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0603_1

- Council of Europe. (2011). The Committee of Ministers to member states on intercultural dialogue and the image of the other in history teaching. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016805cc8e1

- Endacott, J. L., & Sturtz, J. (2014). Historical empathy and pedagogical reasoning. Journal of Social Studies Research, 39, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jssr.2014.05.003

- Erdmann, E., & Hassberg, W. (Eds.). (2011). Facing - mapping - bridging diversity. Hesse, Germany: Wochenshau-Verlag.

- Evans, R. W., Avery, P. G., & Pederson, P. V. (1999). Taboo topics: Cultural restraint on teaching social issues. The Social Studies, 90, 218–224. doi:10.1080/00377999909602419

- Fallace, T. D. (2007). Once more unto the breach: Trying to get preservice teachers to link historiographical knowledge to pedagogy. Theory & Research in Social Education, 35, 427–446. doi:10.1080/00933104.2007.10473343

- Fallace, T. D., & Neem, J. N. (2005). Historiographical thinking: Towards a new approach to preparing history teachers. Theory and Research in Social Education, 33, 329–346. doi:10.1080/00933104.2005.10473285

- Finkelstein, N. (2000). The Holocaust industry: Reflections on the exploitation of Jewish Suffering. New York, NY: Verso.

- Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 219–232. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002

- Goldberg, T. (2013). “It’s in my veins”: Identity and disciplinary practice in students’ discussions of a historical issue. Theory & Research in Social Education, 41, 33–64. doi:10.1080/00933104.2012.757265

- Goldberg, T. (2017). Between trauma and perpetration: Psychoanalytical and social psychological perspectives on difficult histories in the Israeli context. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45, 349–377. doi:10.1080/00933104.2016.1270866

- Goldberg, T., & Savenije, G. M. (2018). Teaching controversial historical issues. In S. A. Metzger & L. M. Harris (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 503–526). Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

- Goldberg, T., Schwarz, B. B., & Porat, D. (2011). “Could they do it differently?”: Narrative and argumentative changes in students’ writing following discussion of “hot” historical issues. Cognition and Instruction, 29, 185–217. doi:10.1080/07370008.2011.556832

- Goldhagen, D. J. (1996). Hitler’s willing executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf.

- Grever, M. (2012). Dilemmas of common and plural history: Reflections on history education and heritage in a globalizing world. In M. Carretero, M. Asensio, & M. Rodriguez-Moneo (Eds.), History education and the construction of national identities (pp. 75–91). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Grever, M., & van Boxtel, C. (2014). Verlangen naar tastbaar verleden: Erfgoedonderwijs en historisch besef [Longing for a tangible past: Heritage education and historical consciousness]. Hilversum, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Verloren.

- Hart, M. T. (2014). The Dutch wars of independence: Warfare and commerce in the Netherlands 1570–1680. London, UK: Routledge.

- Hess, D. E., & McAvoy, P. (2014). The political classroom: Evidence and ethics in democratic education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Huijgen, T., van Boxtel, C., van de Grift, W., & Holthuis, P. (2017). Toward historical perspective taking: Students’ reasoning when contextualizing the actions of people in the past. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45, 110–144. doi:10.1080/00933104.2016.1208597

- Iggers, G. G. (1997). Historiography in the twentieth century: From scientific objectivity to the postmodern challenge. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- James, J. H. (2008). Teachers as protectors: Making sense of preservice teachers’ resistance to interpretation in elementary history teaching. Theory & Research in Social Education, 36, 172–205. doi:10.1080/00933104.2008.10473372

- Jonker, E. (2012). Reflections on history education: Easy and difficult histories. Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 4, 95–110. doi:10.3167/jemms.2012.040107

- Judt, T. (2006). Postwar: A history of Europe since 1945. New York, NY: Penguin.

- King, J. T. (2009). Teaching and learning about controversial issues: Lessons from Northern Ireland. Theory & Research in Social Education, 37, 215–246. doi:10.1080/00933104.2009.10473395

- Kinloch, N. (1998). Learning about the Holocaust: Moral or historical question? Teaching History, 93, 44–46.

- Klein, S. R. (2010). Teaching history in The Netherlands: Teachers’ experiences of a plurality of perspectives. Curriculum Inquiry, 40, 614–634. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2010.00514.x

- Klein, S. R. (2017). Preparing to teach a slavery past: History teachers and educators as navigators of historical distance. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45, 75–109. doi:10.1080/00933104.2016.1213677

- Kosso, P. (2009). The philosophy of history. In A. Tucker (Ed.), Companion to the philosophy of history and historiography (pp. 7–25). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Levisohn, J. A. (2010). Negotiating historical narratives: An epistemology of history for history education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 44, 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9752.2010.00737.x

- Lorenz, C. (1995). Beyond good and evil? The German empire of 1871 and modern German historiography. Journal of Contemporary History, 30, 729–765.

- Martell, C. C. (2013). Learning to teach history as interpretation: A longitudinal study of beginning teachers. Journal of Social Studies Research, 37, 17–31. doi:10.1016/j.jssr.2012.12.001

- McDiarmid, G. W., & Vinten-Johansen, P. (2000). A catwalk across the great divide: Redesigning the history teaching methods course. In P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives (pp. 156–177). New York: New York University Press.