Abstract

Research on party responsiveness in established democracies suggests that parties follow shifts in the preferences of either the general electorate or party supporters. Drawing on theoretical models of party competition and research on party-voter congruence, we argue in this article that in the 21st century Western European mainstream parties respond to their partisan constituents. Parties adjust their policy positions to eliminate previous incongruence between themselves and their constituents and follow the shifts in supporters' positions. Analyses based on a series of datasets that use expert surveys and election surveys to measure parties' positions and several cross-national and national surveys to measure voters' preferences between 1999 and 2014 strongly support the argument that mainstream parties respond to existing incongruence. The findings in this article update many of the empirical results of prior studies on party responsiveness to public opinion shifts, with important ramifications for our understanding of party-based representation in contemporary European democracies.

Mainstream political parties across Western Europe have seen their vote shares drop as challenger parties on both the left and the right made substantial electoral gains in the first two decades of the 21st century (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015). This raises new and important questions about the nature of the ideological connection between political parties and European citizens. Research into the dynamic responsiveness of mainstream/leadership dominated parties in the region reports that these parties follow shifts in the left-right ideological preferences of the general electorate, rather than in the central tendency of their own voters (Adams Citation2012). But these studies were largely based on data that preceded the most substantial changes to party systems that began at the end of last century. A more recent analysis reports almost no evidence that European political parties respond to public opinion at all and calls for better measures of party positions and stronger theories of responsiveness (O’Grady and Abou-Chadi Citation2019).

In this article we answer this call by demonstrating that mainstream parties in contemporary European societies are indeed responsive to public opinion on the left-right dimension, but that the relationship follows a different logic than that emphasised in the existing dynamic responsiveness research. Instead, these parties respond first and foremost by eliminating previous incongruence between their policy positions and those of their supporters. Our theoretical argument draws on significant theoretical work suggesting electoral incentives for parties in multi-party systems to adopt partisan-focused positions, particularly in the context of realigned party politics characterised by high party system fragmentation. We also build on empirical research showing that despite substantial change in the beginning of the 21st century parties seek to stay aligned with their supporters - especially partisan constituents - on the left-right dimension. We suggest that to achieve this congruence, following the shifts in the preferences of partisan constituents is not enough: parties also need to change their policies to eliminate or reduce any previously existing incongruence. Thus, our key theoretical expectations are that mainstream parties respond to their partisan constituents by both closing existing congruence gaps and following the shifts in supporters' positions.

Our empirical analysis covers 14 Western European countries in the period between the late 1990s and mid-2010s and uses Chapel Hill expert surveys (Bakker et al. Citation2015; Polk et al. Citation2017) and national and European election studies for measuring parties' left-right positions. Election studies provide one source of data for measuring voters' preferences, the other being the European Social Survey. Overall, we present three sets of analyses that use different combinations of information sources on parties' and voters' positions, addressing requests for alternative measures of party positions in responsiveness scholarship (O’Grady and Abou-Chadi Citation2019). While each individual data source has its flaws, by combining three different datasets we hope to achieve more robust inferences. Despite the diversity of sources (Adams et al. Citation2019), our findings consistently show mainstream parties that find themselves distant from the mean position of their partisan constituents respond by shifting towards that position, i.e. reducing existing incongruence. However, the analyses demonstrate weaker support for the notion that mainstream parties follow the shifts in the mean partisan supporter position. We further report a consistent lack of support for the argument that parties follow shifts in the overall mean voter position.

Our argument draws on and links two distinct but compatible traditions in the study of party representation that examine congruence and responsiveness. By showing that most parties in established Western European democracies respond to incongruence, we address the theoretical and empirical puzzle that emerges from the findings indicating high congruence between parties and their supporters on the one hand and responsiveness of (mainstream) parties to the general electorate on the other.

Party responsiveness: theoretical expectations

Research on party responsiveness to public opinion shifts in Western Europe has produced two main, interrelated findings: mainstream and/or leadership-dominated parties respond to changes in the central tendency of the general electorate whereas niche and/or activist-dominated parties shift their positions in line with the mean party voter (Adams et al. Citation2006; Ezrow et al. Citation2011; Schumacher et al. Citation2013).Footnote1 Several factors potentially explain why mainstream parties (social democrats, conservatives, Christian Democrats and liberals) would be more likely to respond to the more general mean voter.Footnote2

First, many spatial models of party competition suggest that parties calibrate their positions in line with the mean voter position (Adams and Merrill Citation2009; Lin et al. Citation1999). Second, studies on party alignments and representation emphasise the growth in the number of independent voters, where mainstream Western European parties face a representational tension in attempting to appeal to equally large blocks of partisans and independents (Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012). As a consequence, these parties increasingly have incentives to appeal to the general electorate (Dassonneville Citation2018). Finally, these predominantly office-seeking parties (Strøm and Müller Citation1999) have incentives to be responsive to shifts in the position of the median or average voter in order to be sufficiently moderate for consideration in the formation of government coalitions (Ezrow Citation2008; Lehrer Citation2012).

Despite the value of these contributions, below we present theoretical, empirical and methodological reasons that justify a re-examination of these central findings of the party responsiveness literature in the contemporary era. We begin by highlighting an apparent divergence in the responsiveness and congruence literature. The former expects and finds that mainstream parties respond to the mean voter, thus implying a substantial left-right ideological distance between parties and their partisan constituents. The latter indicates that party-partisan congruence is high, particularly for more centrist, mainstream parties (Costello et al. Citation2012; Dalton Citation1985; Mattila and Raunio Citation2006; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012; Thomassen and Schmitt Citation1997). For example, the correlation between the mean left-right positions of party voters and candidates in the 2009 European Election Studies data was 0.85 (Dalton Citation2017: 612).

There are at least two ways in which these high congruence levels could occur. Voters could adjust their policy preferences or party affiliation in line with shifts in parties' positions. For example, if a party shifts to the right to follow the mean voter, but the mean party voter position does not change, then more leftist party supporters would either switch party affiliation or adopt more rightist policy preferences. In such a scenario, the party would also gain some supporters on the right. Overall, the mean party supporter position also shifts to the right, keeping party-voter congruence high. However, evidence of partisan sorting is rather mixed, particularly on the left-right dimension (Adams Citation2012). Another possibility, which we focus on in this article is that parties actually respond to their supporters, as suggested by recent work on issue attention among US congressional legislators (Barbera et al. Citation2019). They can respond to their supporters by following shifts in their preferences (as suggested in existing literature); and/or by responding to existing incongruence.

The close alignment between parties and their supporters resulting in the divergence of parties' policy positions has not gone unnoticed in the theoretical literature on party spatial competition. Besides policy motivations that might push parties to adopt non-centrist positions, scholars have suggested various theoretical reasons for vote- or office-seeking parties to adopt partisan-oriented, less centrist positions (Grofman Citation2004). In their unified theory of party competition, Adams et al. (Citation2005) explicitly explore the incentives for vote-seeking parties to position close to their core constituencies vs. the central voter. When considering voter partisanship and socio-demographic characteristics, both of which remain important predictors of vote choice above and beyond policy and ideological positions, they show that parties have incentives to position themselves closer to voters that are favourably disposed towards them for these non-policy reasons. This is because parties' policy appeals are unlikely to attract voters who are positively inclined towards other parties for non-policy reasons; positioning closer to partisans/core socio-demographic groups maximises parties' electoral support. The extent to which parties take positions closer to the core constituencies as opposed to the central voter depends on the number of candidates, electoral salience of policies and partisanship, the dispersion of the electorate's policy preferences, the size of partisan constituencies and their policy extremity (Adams et al. Citation2005: 70).

We believe that the theoretical results of Adams, Merrill and Grofman, as well as the broader theoretical literature on party competition, imply that Western European parties should be responsive to the mean partisan voter in the 21st century.Footnote3 While it is undoubtable that significant dealignment of party systems has occurred since the 1960s, the current patterns of party competition more strongly support the realignment perspective (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015). In his recent book, one of the most prominent scholars of dealignment, makes a similar argument (Dalton Citation2018). Both established and younger parties retain (or have obtained) significant partisan followings with diverse and salient policy preferences, thus encouraging the responsiveness of vote-seeking parties to their core clienteles. Party system fragmentation is high, which increases electoral incentives for parties to be responsive to their supporters because the competition for the support of the central voter becomes more electorally risky.Footnote4

We therefore expect parties to respond to their partisan constituents rather than shifts in the central tendency of the electorate at large. We further anticipate that parties respond in a particular way, one that maximises congruence with their partisan supporters. Our argument draws on the dynamic implications of static party-voter congruence studies. In their recent overview of the congruence research, Golder and Ferland (Citation2018) encourage dynamic responsiveness scholars to consider both party responses to voter position shifts and previous party-voter incongruence within a single theoretical framework. These authors suggest that parties respond not only to the shifts in voters' positions (as per arguments in the research on party responsiveness), but also to the previous incongruence between themselves and voters, because congruence between parties' and voters' positions is the ‘ultimate goal’ which can be achieved through responsiveness (Golder and Ferland Citation2018: 215). This expectation is also consistent with the empirical evidence which shows that left-right ideological congruence between parties and their voters is indeed high (Dalton et al. 2011; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012).

Following these arguments, we theorise that contemporary mainstream parties in Western Europe have strong incentives to eliminate prior incongruence by moving towards their partisan supporters' positions. Thus, for example, if the party observes that in the recent past (say, one or a few years) the average partisan constituent is to the right of the party's position, and remains stable, the party would move to the right to remove this incongruence. The higher this initial distance, the more substantial the subsequent change in the party's position. This implies the following hypothesis:

Party Supporter Congruence Gap Hypothesis: Mainstream political parties respond to incongruence between the party and its partisan constituents by shifting towards their partisan supporters, i.e. reducing the existing party-supporter ideological gap.

We also note that staying congruent with its partisan supporters may require the party not only to eliminate prior incongruence, but also shift its position in line with the change in its supporters' preferences. The latter type of responsiveness has been found to be a strategy of niche parties (Ezrow et al. Citation2011; Schumacher et al. Citation2013). However, unlike these studies, we argue that the overall response of the party to public opinion is driven by both previous incongruence and the subsequent shift in public opinion. To continue with the previous example, if the party observes that recently the average partisan supporter was to the right of the party's position, but it then moves to the left, the party would not have incentives to change its position because it is likely to end up being congruent with its supporters. This change in the position of the party's voters should unequivocally lead to a similarly sized change in the party's position only if the party was aligned with the mean supporter position to start with. These arguments imply that, all else (including prior incongruence) equal, the party should follow the shifts in the mean partisan constituent position:

Party Supporter Change Hypothesis: Mainstream political parties change their positions in line with the shifts in the mean partisan constituent position.

Summarising, we have several reasons to suggest that mainstream parties are likely to be responsive to the preferences of their (partisan) supporters in the early 21st century. We have worked to bring the responsiveness and congruence literatures together, where the latter shows high congruence between parties and their supporters that potentially results from parties responding to their supporters. We also presented a number of theoretical explanations for the divergence in parties' policy positions and responsiveness to their supporters in the context of substantial realignments that have taken place in the early 21st century. These include the presence of high party system fragmentation, significant size of partisan clienteles with distinct policy preferences and the electoral salience of voters' policy preferences and partisanship. Finally, we note that prior research is heavily dependent on estimates of party positions that are based on manifestos, which could complicate measures of party-partisan congruence. We expand on this last point in the next section of the article.

Research design

Our hypotheses that mainstream parties will be responsive to the ideological preferences of their supporters rather than the general electorate goes against much of the literature on party policy shifts, but they are in line with research on left-right congruence. At least in part, these differences could be related to the data sources used. Most studies of party responsiveness use Manifesto Project (MARPOR) data to estimate the positions of political parties. This is largely because MARPOR data offer unparalleled ability to measure party positions back in time, in some cases as far back as the beginning of the post-war era (Budge et al. Citation2001; Klingemann et al. 2006). Yet, recent research calls into question the extent to which citizens perceive ideological positions as recorded in party manifestos (Adams et al. Citation2014; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013).Footnote5 What is more, the ability to extend analysis back to the mid-20th century is less of a distinct advantage when looking at the dynamic responsiveness of political parties in the era of de/realignment for which alternate sources of data on party positioning, such as expert surveys, are more widely available. Finally, the inability of O’Grady and Abou-Chadi (Citation2019) to detect party responsiveness to public opinion across Europe led these authors to recommend examining party positions with different data sources. It may be that congruence scholars come to different conclusions than much of the existing research on party responsiveness in Western Europe because in addition to covering a different, more recent, time period, they also use different sources of data, namely an expert survey for parties and the European Social Survey (ESS) for the public.

Our empirical analysis therefore uses information from a combination of expert and public opinion surveys for 14 member states of the European Union in Western Europe.Footnote6 Unlike some other Western European democracies, all these countries were included in the first five waves of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) on party positioning in Europe (1999, 2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014), thus providing us with time-series dataset on parties' positions. Excluding countries in Central and Eastern Europe is in line with our focus on established democracies.

From the CHES dataset we use the question in which experts are asked to place parties on the left-right dimension in terms of their overall ideological stances. The question uses an 11-item scale in which 0 and 10 represent the most leftist and rightist positions, respectively. We use the mean expert placement as an estimate of the party's position and compute the change in the party's policy position as the difference between its left-right positions in two consecutive CHES waves.

In order to strengthen our inferences, and in line with the research on ideological congruence (e.g. Golder and Stramski Citation2010), we also employ mass survey-based placements by voters as another way to measure parties' policy positions. To make the two sets of analyses as comparable as possible, the mass survey-based measure was constructed for the same 14 countries and roughly same time period (1999–2014) as the one examined using the CHES dataset. Specifically, we used the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) (CSES Citation2020) or national election surveys whenever they were available; where they were not available, we complemented them with the surveys from the European Election Study (Egmond et al. Citation2014; Schmitt et al. Citation2009; Citation2016) conducted close to the national election years. We use the questions in which respondents were asked to place individual parties on a 0 to 10 scale for the left-right dimension. Where an original scale was different, it was recoded to the 11-item scale. A party's policy position is estimated as a mean placement of it by the respondents. The shift in a party's policy position is computed by taking the difference between its positions in each pair of surveys.

The same set of surveys was also used to measure voters' ideological preferences and combined with each of the two datasets on parties' positions. Additionally, we also use the European Social Survey (ESS) (European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1-9 Citation2020) in combination with the CHES expert surveys. The ESS matches the timing of the CHES expert surveys better than the election surveys and, unlike the latter, is a single cross-national survey. However, it does not include questions on voter placements of parties' positions and therefore was not available as a source on parties' policy positions.

In both sets of survey datasets, voters' policy positions are estimated based on the question in which they were asked to place themselves on the left-right scale. Where an original scale was not an 11-item scale, it was recoded to such. The predictor variable to test the Congruence Gap Hypothesis, coded on the basis of this information, is the difference between the mean position of the voters who self-identified as partisans of the party (partisan constituents) and the party position. Negative values of this variable indicate that the mean partisan constituent was to the left of the party and, conversely, positive values occur when the mean partisan constituent was to the right of the party's position. For the Supporter Change Hypothesis, we use a variable capturing the change in the mean position of partisan constituents. The hypothesis implies a positive effect of this variable.

Turning to the time lags in our central measures, changes in party positions are measured from time t to t + 1, and the congruence gap is measured at time t. The analysis for the Supporter Change Hypothesis, uses changes in the partisan position in the period between t and t + 1.

Voter partisanship is determined based on the questions on respondents' closeness to parties. The wording of this question differed somewhat across the surveys used. To make the results from different surveys more comparable, we developed a broad measure of partisanship that included both strong and weak partisans. This is in line with the findings of Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012: 114), who report that the main dividing line in the patterns of representation is between all partisans on the one hand and independents on the other. At least 10 respondents reporting partisanship with the party were required for it to be included in the analysis.

We develop several other public opinion variables for either robustness checks or as control variables. Following the literature on party responsiveness that tends to focus on party voters as opposed to partisan identifiers, we measure the distance between the mean party voter position and the party position as well as the change in the mean position of the party voter. Party voters were identified based on the reported vote in the last national election or vote intention in the next national election, depending on the availability of questions in the surveys used. This measure differs in two respects from the one that uses partisan constituents. First, it includes both partisan and independent voters for the party. Second, it includes only voters while the measure using partisan constituents also considers the abstainer partisans.

Another set of measures controls for party responsiveness to the general electorate suggested by the literature. In line with the representational strain argument, in the main set of analyses we compute the measure capturing the change in the mean independent voter position.Footnote7

We use the party family codes available in the CHES dataset to identify mainstream parties. The social democrats, conservatives, Christian democrats, agrarians and liberals were coded as mainstream parties and are the focus of our analysis.Footnote8

We include a control variable for the change in economic growth between the end and beginning of each time period considered, following work that highlights the importance of the broader macroeconomic environment (e.g. Ezrow and Hellwig Citation2014). Higher growth might push parties to adopt more fiscally expansive strategies while slowing growth or recession could lead them to switch to more economically conservative positions. Finally, earlier work on party policy change also emphasises the importance of controlling for previous shifts in party policy positions (i.e. the lagged dependent variable) as parties, for example, may alternate with shifts to opposite directions across multiple electoral periods (Budge Citation1994).

summarises the descriptive statistics for the main variables used in the analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Results

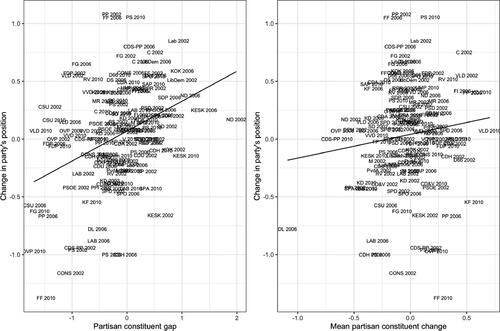

We begin by presenting () the bivariate scatterplots of the change in parties' left-right positions and each of the two independent variables. We note that although changes in party positions tend to be rather small, as expected, shifts of between 0.5 to 1.0 points on the 0–10 left-right scale are also common. The Congruence Gap Hypothesis is tested by the variable measuring the distance between the mean partisan constituent position and party's position at the beginning of the time or electoral period. The predictor variable capturing the shift in the mean partisan constituent position is used to test the Supporter Change Hypothesis. The data from CHES expert surveys and ESS are used for these scatterplots, but other datasets show similar patterns.

Figure 1. Partisan constituent gap, mean partisan constituent change and party policy change.

Note: CHES for parties' positions and ESS for voters' positions. Years indicate the start of the period for which change is measured. Partisan constituent gap measured as the difference between the mean partisan constituent position and the party's position.

The first plot shows a clear positive relationship between the party-supporter incongruence and subsequent shifts in parties' positions, thus providing initial support for the Party Supporter Gap Hypothesis. Parties whose supporters are mostly to the right of them tend to move rightward. Conversely, parties with supporters to the left of them tend to shift leftward. This is an important finding given that the variation in both variables is moderate (Dalton et al. 2011; Dalton and McAllister Citation2015). More specifically, the mean value of the absolute constituent gap is 0.76 and the mean absolute change in parties' left-right positions is 0.38. Parties rarely undertake large changes in their ideological positions, but even when they shift moderately they calibrate these changes to increase congruence with their supporters. However, the second plot indicates a weaker positive relationship between the change in the mean supporter position and the change in party's position. The Party Supporter Change Hypothesis is thus less supported, a finding that is confirmed by the regression analyses.

reports linear regression models for all three datasets (CHES + ESS; CHES and election surveys; and election surveys used for both parties' and voters' positions). For each dataset, one model is fit with party-supporter incongruence, second with party supporter change, and the third one with both predictor variables. All models also include the change in the mean independent voter position, the change in economic growth, lagged change in party's left-right positions and country fixed effects (the latter are not reported). The data are nested within country-time period dyads (when CHES data is used to measure parties' policy positions) or electoral periods (when election surveys are a source of information on parties' left-right positions) as well as political parties (all datasets). We therefore include random intercepts for these levels.

Table 2. Linear multi-level models of party policy change.

The results provide strong support for the Congruence Gap Hypothesis. The partisan constituent gap variable is statistically significant in all six models in which it is included. The size of the effects is substantial. Specifically, for each point in the distance between the party and its partisan constituents, the party shifts its position by somewhere between 0.35 and 0.45 points. Thus, for example, if the mean supporter position is one point to the right of the party's position, all else equal the party would shift its policy position to the right by 0.35 to 0.45 points. While this falls short of a one-to-one relationship between incongruence and responsiveness (which is unlikely to be uncovered even if it exists due to random error in the measures of parties' and voters' positions), the evidence strongly supports the notion that mainstream parties substantially try to reduce such incongruence by moving closer to their supporters.

Importantly, the substantive size of the effects is moderately but consistently larger in the models where the change in the mean partisan constituent position is also an explanatory variable in comparison to the models where this variable is excluded. The two explanatory variables are moderately correlated (between −0.15 and −0.31 in the three datasets), thus suggesting a partisan sorting process in which the supporters of the party that are further away from its position either shift their positions towards those of the party or change their party affiliation. Including both variables in the regression analysis helps to isolate the direct effect of party-supporter gaps on party policy shifts, without an offset created by a party's responsiveness to the change in the mean supporter position towards its initial position that resulted from this gap. Nevertheless, even when the party supporter change variable is excluded, the substantive effects of party-supporter gap remain quite large (0.3–0.4 points).

The Party Supporter Change Hypothesis receives more limited empirical support. The change in the mean partisan constituent position is statistically significant in the models using CHES/ESS and election survey data (Models 2, 3, 8 and 9), but not when CHES and election survey data are combined (Models 5 and 6). The magnitude of the effect increases when the party-supporter gap variable is included, thus eliminating the omitted variable bias resulting from the mean supporter change variable partially capturing the direct effect of party-supporter gaps on party policy changes. Where the variable is statistically significant, its effect is quite large and ranges between 0.29 and 0.52.

Both substantive and methodological reasons can potentially account for weaker support to the Party Supporter Change Hypothesis. Substantively, parties face greater informational and organisational constraints to respond to shifts in supporters' preferences. On the informational front, parties may struggle to collect and make sense of the signals from their organisations and public opinion polls about the on-going changes in their supporters' preferences. Such informational challenges are less present when parties have a few years perspective over public opinion. Furthermore, parties may take time to develop policies in response to public opinion as various actors in party organisations need to agree to them. Methodologically, measures in the shifts in the supporters' preferences are more susceptible to random error as they use small samples in two surveys. While this is also an issue for measuring the distance between a party and its supporters, in the latter case it is much less so because a single mass survey is used.

A separate methodological issue with the Party Supporter Change Hypothesis is that shifts in supporters' preferences might also be driven by party policy shifts in line with the partisan sorting process (Adams et al. Citation2014).Footnote9 If such a partisan sorting process takes place, we should also observe shifts in average supporter perceptions driven by actual parties' positions. The lack of shifts in supporters' perceptions would be hard to imagine if they respond to parties' policy shifts. In Online appendix 1 we present evidence showing that the average supporter perceptions of parties' policy positions are indeed correlated with contemporaneous changes in parties' positions. While this evidence is also compatible with the party responsiveness account (i.e. with parties responding to shifts in supporters' preferences, and supporters subsequently noticing party policy change), it nevertheless questions the extent of empirical support for the Party Supporter Change Hypothesis.

Another important finding that emerges from is the lack of support for the argument that parties respond to the shifts in the mean independent voter position. This supports our expectations that mainstream parties respond to representational strain by prioritising responsiveness to their partisan constituents as opposed to independent voters and is in line with empirical evidence showing substantial distance between parties and the mean independent voter (Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012). Even if responding to independent voters might provide electoral benefits, it is a challenge due to the heterogeneity in the preferences of independent voters.

With regard to control variables, we find strong effects of economic growth when using the CHES + ESS data, but less so for the other two datasets. Lagged policy change has a consistent negative effect across all models, in line with the findings in the literature, although the coefficient of this variable is statistically significant in only some of the models. Interestingly, the effect of the lagged dependent variable weakens when the constituent gap variable is included in the models. This suggests a plausible interpretation for the tendency of parties to alternate the direction of shift in consecutive elections (Budge Citation1994). For example, observing at time t that most of its supporters are to the right of its position, a party shifts to the right between t and t + 1 to close this gap. However, subsequently at time t + 1 the party may find itself to the right of many of its supporters. This could be because the party shifted too much to the right and/or, in line with the partisan sorting argument, many of its more rightist supporters responded to the gap at time t by either switching their support to another party or adopting more leftist positions in the period between t and t + 1. Observing the new gap at t + 1, the party moves to the left in the period between t + 1 and t + 2.

We present several robustness cheques in the appendices.Footnote10 Online appendix 2 shows the set of analyses in which we use mean party voter position when testing our two key hypotheses. Furthermore, the shift in the mean voter position is used in these analyses. The results still indicate strong support for the Party Supporter Congruence Gap Hypothesis: the distance between the mean voter position and party's position remains statistically significant for all models. The strength of the effects is however somewhat weaker in all models of mainstream parties, thus supporting the argument that these parties first and foremost respond to their partisan constituents as opposed to independent voters who voted for them.

The change in the mean party voter position is statistically significant for all three datasets (as long as the party-voter gap variable is also included). However, given the potential endogeneity of this effect, we consider the support for this hypothesis as mixed.

Importantly, the shift in the mean voter position does not have a statistically significant effect on the change in parties' policy in any of the models. This complements our main findings about the lack of party responsiveness to the mean independent voter, and reinforces our finding showing no support for the expectation that mainstream parties respond to the central tendency of the electorate as operationalised by the mean voter position or the mean independent voter.Footnote11

Online appendix 3 presents series of analyses testing these relationships with regard to niche parties. The key finding from these analyses is weaker or no support for the Party Supporter Congruence Gap Hypothesis for the parties with a niche profile.Footnote12 This supports the findings of Bischof and Wagner (Citation2020: 392), who argue that parties with niche issue focus ‘will mostly be interested in their core issue and will therefore pay less attention to public opinion change on the broader left-right dimension’. Further, no evidence was found on the interactive effect of other conceptions of party nicheness.

Online appendix 4 shows analyses that also control for party family. Online appendix 5 shows ordinal regression analyses that use a three-category variable (statistically significant change to the left; no statistically significant change; statistically significant change to the right). To establish the statistical significance of change, we compare mean party placements by experts (CHES data) and voters (election survey data) using one-way t-tests. Online appendix 6 shows the analyses with a party’s position at time point t + 1 as the dependent variable while controlling for a party’s position at time point t. Online appendix 7 shows analyses for the subset of the data in which CHES expert surveys were conducted in election years or one year later. Online appendix 8 show linear regression models with robust standard errors clustered by elections. The estimates from all of these models are similar to those reported in of the manuscript.

Conclusion

This article qualifies much of the received wisdom about party responsiveness to shifts in the left-right ideological orientation of citizens in European democracies (cf. Adams Citation2012). Consistent with O’Grady and Abou-Chadi (Citation2019), we find no evidence that mainstream parties respond to changes in the average position of the general electorate in our analysis of 14 Western European democracies between 1999 and 2014. Instead, we report that mainstream parties display a different form of responsiveness by attempting to close pre-existing ideological congruence gaps between themselves and their partisan constituents. These findings support our theoretical expectations derived from research on mass-elite congruence (Golder and Ferland Citation2018), party alignments (Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2012) and spatial party competition (Adams et al. Citation2005).

We note that our findings differ from the expectations derived from previous research on the dynamic responsiveness of political parties in Western Europe. Since our empirical focus was on the 21st century, we can only speculate why this could be the case. We consider that our theoretical logic is applicable to earlier eras of party competition. At the same time, we note that party fragmentation and realignment have altered party systems to a substantial degree. Mainstream parties in the early 21st century rarely receive above 30 percent of the vote, and formerly dominant centre-left parties experienced existentially dramatic electoral declines in, for example, France, Italy and the Netherlands. The canonical research on party responsiveness in this region uses data that precede these more recent developments. Our analysis, in contrast, focuses almost exclusively on the early part of the 21st century.

In addition to different time periods, the present analysis uses different data sources to estimate the positions of both the public and parties than the earlier research. The European Social Survey, a central source of information for the public in our article, was not available prior to 2002, and the majority of previous research operationalised party positions exclusively through manifesto data. Although our findings diverge from the research on public opinion and party policy change in important ways, we have more confidence in the somewhat unconventional conclusions we present because they are based on three distinct datasets that operationalise our key concepts differently yet still yield similar results. This last point is particularly striking and important given evidence that alternative measures of party shifts correlate less strongly than expected (Adams et al. Citation2019) and that voter and particularly party positions are rather stable, and positional shifts tend to be small (Dalton et al. 2011; Dalton and McAllister Citation2015; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). In sum, our analyses, based on a variety of data sources, return a consistent lack of support for the idea that Western European political parties follow shifts in the overall mean voter position, and lead us to reject this hypothesis.

Incorporating a fuller range of the diverse sources of information on citizen preferences and party positions within studies of mass-elite representation is a central recommendation for future research given its fruitful application here. Another would be to further push the integration of congruence and responsiveness research, bodies of literature that have existed in close parallel with one another yet directly engage to a surprisingly limited degree. Such efforts could also extend back to earlier time periods than the one covered here, even if such an endeavour presents important methodological challenges for measuring party-voter congruence. Finally, our results invite additional scrutiny based on analyses within a multidimensional setup (following, e.g., O’Grady and Abou-Chadi Citation2019). Although we focus on mainstream party responsiveness on the left-right dimension within this article, we fully expect niche parties could be and probably are more responsive on dimensions more central to their party brand or on which mainstream parties are constrained (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2016; Williams and Spoon Citation2015). Our results highlight the importance of studying party-voter congruence and responsiveness in tandem when assessing political representation in the early decades of the 21st century.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (5.5 MB)Acknowledgements

Author order is alphabetical. Jonathan Polk acknowledges research funding from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) [grant 2016-01810] and Riksbankens Jubileumsfond [grant P13-1090:1]. This research benefited from participant comments in seminars and workshops at the University of Bergen, University of Copenhagen, University of North Carolina, the 2018 ECPR general conference and the 2018 EPSA annual conference. We also appreciate helpful suggestions from Ryan Bakker, Adriana Bunea, Will Jennings, Seth Jolly, Caroline Lancaster, Eva Heiða Önnudóttir, Karina Kosiara-Pedersen, Sebastian Popa, Anne Rasmussen, and the editors and anonymous reviewers at West European Politics.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Raimondas Ibenskas

Raimondas Ibenskas is Associate Professor at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen. His research focuses on political parties and representation in a comparative perspective and interest groups in the European Union. He has published articles in the British Journal of Political Science, European Journal of Political Research, Journal of Politics, and other political science journals. [[email protected]]

Jonathan Polk

Jonathan Polk is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen and University of Gothenburg. His research focuses on political parties, representation and European politics. He has published articles in Comparative Political Studies, Journal of European Public Policy, Journal of Politics, and other political science journals. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The opposite direction of causal relationship – voters taking cues from parties' positions – is of course important to consider. We discuss this possibility in the results section.

2 In line with most literature on the effect of public opinion on party policy, we use the mean as a statistic of the central point in the voter distribution.

3 We also find these theoretical results compatible with the idea of this type of responsiveness throughout the post-war period. Since the 20th century is not our empirical focus, we avoid making a strong claim on this.

4 Other static models of party competition (e.g. Cox Citation1990) also imply that higher fragmentation increases parties' policy extremity. Further, a dynamic model of party competition (Laver and Sergenti Citation2012: 143–144) shows that, when the number of parties is high, the Aggregator strategy (taking the mean position of party supporters) brings higher or at least the same electoral success as vote-seeking strategies.

5 But see also Fernandez-Vazquez (Citation2014).

6 At the time of writing this article, the UK was a member state of the EU. Luxembourg is the only country in EU-15 not considered.

7 Rohrschneider and Whitefield (Citation2012: 26) report that 45% of the voters in Western Europe are independents. This is in line with our data. The shift in the mean independent voter position correlates with the shift in the mean voter position at 0.6 (ESS) and 0.81 (election surveys). In the additional models that use the mean party voter position we follow the literature on responsiveness (e.g. Adams et al. Citation2004) by using the change in the mean voter position and find results substantively similar to our primary analysis.

8 We do not expect for our hypotheses to be supported for niche parties. To test this expectation empirically, we present in the appendices the same set of models for niche parties. The greens, radical right, regionalist, confessional and radical left parties were coded as niche parties. This inclusive approach to the coding of niche parties reduces the possibility that our main analyses capture parties that are characterised by at least some of the niche party characteristics summarised by Bischof and Wagner (Citation2020) (policy-seeking goals, activist dominance, and ideological nicheness) to at least a moderate extent. Online appendix 3 presents the results of the models using both mainstream and niche parties in which three variables of public opinion (party-constituent incongruence, change in the preferences of party constituents, and change in the positions of the mean independent voter) are interacted with each of the three niche party characteristics.

9 Such endogeneity concerns are not an issue when testing the Party Congruence Gap Hypothesis because incongruence between parties' and voters' positions are measured prior to the change in party's policy.

10 Besides these tests, we also examine the possibility that parties in opposition and parties functioning under more proportional electoral systems are more responsive to their supporters. The effect of opposition party status was present (in terms of increasing responsiveness to party supporter gap) in one set of analysis (CHES + ESS), but not others. The results for electoral system (measured by the natural logarithm of mean district magnitude) showed lower responsiveness to party supporter gap under more proportional systems, but this finding was driven by the Netherlands, and disappeared entirely once this country was excluded from analysis.

11 We examine responsiveness to the general electorate by examining shifts in the mean (independent) voter position. As mentioned in the research design section, this follows what is the most established empirical approach in relevant literature. In additional set of models not reported here we also include the gap between the party's position and the mean (independent) voter position. These variables had no effect in any of the models.

12 These parties are defined and measured as parties ‘competing on niche market segments neglected by their competitors and not discussing a broad range of these segments’ (Bischof and Wagner Citation2020: 394).

References

- Adams, James (2012). ‘Causes and Electoral Consequences of Party Policy Shifts in Multiparty Elections: Theoretical Results and Empirical Evidence’, Annual Review of Political Science, 15:1, 401–19.

- Adams, James, Luca Bernardi, Lawrence Ezrow, Oakley B. Gordon, Tzu‐Ping Liu, and M. Christine Phillips (2019). ‘A Problem with Empirical Studies of Party Policy Shifts: Alternative Measures of Party Shifts Are Uncorrelated’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:4, 1234–44.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow (2004). ‘Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or to Past Election Results?’, British Journal of Political Science, 34:4, 589–610.

- Adams, James, Michael Clark, Lawrence Ezrow, and Garrett Glasgow (2006). ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976-1998’, American Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 513–29.

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu (2014). ‘Do Voters Respond to Party Manifestos or to a Wider Information Environment? An Analysis of Mass-Elite Linkages on European Integration’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 967–78.

- Adams, James, and Samuel Merrill (2009). ‘Policy-Seeking Parties in a Parliamentary Democracy with Proportional Representation: A Valence-Uncertainty Model’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:3, 539–58.

- Adams, James F., Samuel Merrill, and Bernard Grofman (2005). A Unified Theory of Party Competition: A Cross-National Analysis Integrating Spatial and Behavioral Factors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bakker, Ryan, Catherine De Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, et al. (2015). ‘“Measuring Party Positions in Europe the Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File”, 1999-2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Barbera, Pablo, Andreu Casas, Jonathan Nagler, Patrick J. Egan, Richard Bonneau, John T. Jost, and Joshua A. Tucker (2019). ‘Who Leads? Who Follows? Measuring Issue Attention and Agenda Setting by Legislators and the Mass Public Using Social Media Data’, American Political Science Review, 113:4, 883–901.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Markus Wagner (2020). ‘What Makes Parties Adapt to Voter Preferences? The Role of Party Organisation, Goals and Ideology’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 391–401.

- Budge, Ian (1994). ‘A New Spatial Theory of Party Competition: Uncertainty, Ideology and Policy Equilibria Viewed Comparatively and Temporally’, British Journal of Political Science, 24:4, 443–67.

- Budge, Ian, Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Eric Fording, Rirchard C. Tanenbaum, Derek J. Hearl, et al. (2001). Mapping Policy Preferences. Estimates for Parties, Electors, and Governments 1945-1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (2020). Available at http://www.cses.org.

- Costello, Rory, Jacques Thomassen, and Martin Rosema (2012). ‘European Parliament Elections and Political Representation: Policy Congruence between Voters and Parties’, West European Politics, 35:6, 1226–48.

- Cox, Gary W. (1990). ‘Centripetal and Centrifugal Incentives in Electoral Systems’, American Journal of Political Science, 34:4, 903–35.

- Dalton, Russell J. (1985). ‘Political Parties and Political Representation Party Supporters and Party Elites in Nine Nations’, Comparative Political Studies, 18:3, 267–99.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2017). ‘Party Representation across Multiple Issue Dimensions’, Party Politics, 23:6, 609–22.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2018). Political Realignment: Economics, Culture, and Electoral Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, Russell J., David M., Farrell, and Ian McAllister (2011). Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Ian McAllister (2015). ‘Random Walk or Planned Excursion? Continuity and Change in the Left-Right Positions of Political Parties’, Comparative Political Studies, 48:6, 759–87.

- Dassonneville, Ruth (2018). ‘Electoral Volatility and Parties; Ideological Responsiveness’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 808–28.

- Egmond, Marcel van, Wouter van der Brug, Sara Hobolt, Mark Franklin, and Eliyahu V. Sapir (2014). European Parliament Election Study 2009, Voter Study. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5055 Data file Version 1.1.0.

- European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1-9 (2020). Data file edition 1.0. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Norway - Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS-CUMULATIVE.

- Ezrow, Lawrence (2008). ‘Parties; Policy Programmes and the Dog That Didn’t Bark: No Evidence That Proportional Systems Promote Extreme Party Positioning’, British Journal of Political Science, 38:3, 479–97.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, Catherine De Vries, Marco Steenbergen, and Erica Edwards (2011). ‘Mean Voter Representation and Partisan Constituency Representation: Do Parties Respond to the Mean Voter Position or to Their Supporters?’, Party Politics, 17:3, 275–301.

- Ezrow, Lawrence, and Timothy Hellwig (2014). ‘Responding to Voters or Responding to Markets? Political Parties and Public Opinion in an Era of Globalization’, International Studies Quarterly, 58:4, 816–82.

- Fernandez-Vazquez, Pablo (2014). ‘And yet It Moves: The Effect of Election Platforms on Party Policy Images’, Comparative Political Studies, 47:14, 1919–44.

- Fortunato, David, and Randolph T. Stevenson (2013). ‘Perceptions of Partisan Ideologies: The Effect of Coalition Participation’, American Journal of Political Science, 57:2, 459–77.

- Golder, Matt, and Benjamin Ferland (2018). ‘Electoral Rules and Citizen-Elite Ideological Congruence’, in Erik S. Herron, Robert J. Pekkanen, and Matthew S. Shugart (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 213–46.

- Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski (2010). ‘Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:1, 90–106.

- Grofman, Bernard (2004). ‘Downs and Two-Party Convergence’, Annual Review of Political Science. 7, 25–46.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine E. de Vries (2015). ‘Issue Entrepreneurship and Multiparty Competition’, Comparative Political Studies, 48:9, 1159–85.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Philipp Rehm (2015). ‘Party Alignments: Change and Continuity’, in Pablo Beramendi, Silja Hausermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 179–201.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, and Michael McDonald (2006). Mapping Policy Preferences II. Estimates for Parties, Electors and Governments in Eastern Europe, the European Union and the OECD, 1990-2003. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Ernest Sergenti (2012). Party Competition: An Agent-Based Model. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lehrer, Roni (2012). ‘Intra-Party Democracy and Party Responsiveness’, West European Politics, 35:6, 1295–319.

- Lin, Tse-Min, James M. Enelow, and Han Dorussen (1999). ‘Equilibrium in Multicandidate Probabilistic Spatial Voting’, Public Choice, 98:1/2, 59–82.

- Mattila, Mikko, and Tapio Raunio (2006). ‘Cautious Voters-Supportive Parties: Opinion Congruence between Voters and Parties on the EU Dimension’, European Union Politics, 7:4, 427–49.

- O’Grady, Tom, and Tarik Abou-Chadi (2019). ‘Not so Responsive after All: European Parties Do Not Respond to Public Opinion Shifts across Multiple Issue Dimensions’, Research and Politics, 6:4, 1–7.

- Polk, Jonathan, Jan Rovny, Ryan Bakker, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Jelle Koedam, et al. (2017). ‘Explaining the Salience of Anti-Elitism and Reducing Political Corruption for Political Parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey Data’, Research and Politics, 4:1, 1–9.

- Rohrschneider, Robert, and Stephen Whitefield (2012). The Strain of Representation: How Parties Represent Diverse Voters in Western and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rohrschneider, Robert, and Stephen Whitefield (2016). ‘Responding to Growing European Union-Skepticism? The Stances of Political Parties toward European Integration in Western and Eastern Europe following the Financial Crisis’, European Union Politics, 17:1, 138–61.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Stefano Bartolini, Wouter van der Brug, Cees van der Eijk, Mark Franklin, Dieter Fuchs, Gabor Toka, et al. (2009). ‘European Election Study 2004’ (2nd edition). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA4566 Data file Version 2.0.0.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Sara B. Hobolt, Sebastian A. Popa, and Eftichia Teperoglou (2016). ‘European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study, First Post-Election Survey’. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5160 Data file Version 4.0.0.

- Schumacher, Gijs, Catherine de Vries, and Barbara Vis (2013). ‘Why Do Parties Change Position? Party Organization and Environmental Incentives’, The Journal of Politics, 75:2, 464–77.

- Strøm, Kaare, and Wolfgang C. Müller (1999). ‘Political Parties and Hard Choices’, in Wolfgang C. Müller and Kaare Strøm (eds.), Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–35.

- Thomassen, Jacques, and Hermann Schmitt (1997). ‘Policy Representation’, European Journal of Political Research, 32:2, 165–84.

- Williams, Christopher, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2015). ‘Differentiated Party Response: The Effect of Euroskeptic Public Opinion on Party Positions’, European Union Politics, 16:2, 176–93.