Abstract

The literature on the participation paradox, stealth democracy, political transformation and populism implicitly refers to the existence of different participation profiles, but its empirical evidence focuses on separate actions. While several studies have examined the existence of distinct combinations of actions, such participation profiles have rarely been placed within a theoretical framework or connected to the motivations and resources that shape participation. In this article these connections are given a theoretical basis and empirically tested via latent class analysis of a unique set of 12 different political activities. After establishing the participation profiles, it is assessed how political motivations (e.g. interest, efficacy) and resources (time and skills) explain profile membership by using fractional multinomial logistic regression models. Combining these two steps helps to reassess what levels of political participation actually imply for the functioning of our democracies. Crucially, the participation elite is small; faithful voters are numerous but not particularly engaged; and systemically dissatisfied citizens tend to disengage – only a few try to transform the system.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.2017612 .

Electoral participation is declining across Western democracies. Some argue that this is detrimental to the functioning of democracy and democratic legitimacy (Arendt Citation1958; Verba et al. Citation1995), others consider it a sign that people are content (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Citation2002), while a third group stresses that with the emergence of new forms of offline and online political participation, it is the nature of such participation that has changed, not the degree (Inglehart and Catterberg Citation2002; Norris Citation2002; Ohme et al. Citation2018; Theocharis and Van Deth Citation2018). Understanding patterns of participation is crucial for the state of democracy; this study argues and demonstrates that achieving this lies partly in grasping how people combine a variety of actions, and how their political motivations and resources steer them towards certain combinations.

Some may be more inclined to participate in the electoral system, considering that this is sufficient for their aims, as they trust the system. Others might participate outside the system due to distrust, while distrust might also lead to them combining protest and electoral participation to garner systemic change. Similarly, being politically active on social media or casting a vote are likely to have different roots and should be interpreted differently. Social media use can be party-related as well as a means of fighting the system. And casting a vote in parliamentary elections has rather different implications when it is someone’s only political act as opposed to part of a larger repertoire. While very valuable, existing studies explaining specific political actions (or indices thereof) easily lead to diluted or conflated effects (Sinclair-Chapman et al. Citation2009).

In order to further our understanding of democratic political participation in line with the above discussion, this study is centred around two questions:

What different political participation profiles can we identify?

To what extent can different resources and political motivations explain citizens’ participation profiles?

The theoretical answer as to how citizens combine actions is partly present in the existing political science literature, but it is disjointed and never quite comes into focus. For instance, the ‘participation paradox’ implicitly refers to a cluster of citizens who participate in all types of politics (Kern and Hooghe Citation2018; Schlozman et al. Citation2012), while ‘transformation of political participation’ studies implicitly refer to citizens who refrain from participating in electoral politics, only participating in unconventional forms of politics, alongside citizens who do nothing but participate in electoral politics (Copeland Citation2014; Dalton Citation2008). Such implicit profiles are also found in the literature on populism and stealth democracy (Jacobs et al. Citation2018; Jeroense et al. Citation2021; Webb Citation2013). Thus, the literature steers us towards understanding participation in terms of clustering activities, and the question as to which clusters are most prevalent.

More recently, several studies have introduced latent class analysis (LCA) to identify such political participant profiles, and have linked these profiles to factors such as personality, grievances, political preferences, knowledge and interest (Alvarez et al. Citation2017; Johann Citation2012; Johann et al. Citation2020; Keating and Melis Citation2017; Oser Citation2017, Citation2021; Oser et al. Citation2013, Citation2014). We expand on these studies in three ways: (1) we present a comprehensive theoretical understanding of the participation profiles grounded in the ‘participation and democracy’ literature; (2) empirically, we cover a wider range of actions, including multiple ballot box and online activities, allowing for a more precise assessment of activity clustering; and (3) we theoretically and empirically connect the profiles to citizens’ political motivations and resources (e.g. Norris Citation2002; Verba et al. Citation1995), deepening our understanding of the profiles and motivations’ and resources’ multifinal and equifinal impact on political participation.

Case-wise, we study the Netherlands, a fairly typical Western European democracy where voting is not compulsory. Also, the Dutch LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel data offers a uniquely wide variety of acts: 12 conventional, unconventional and digital political activities. Some features specific to the Netherlands, like relatively high turnout, do of course demand that care is taken not to overgeneralise, even though wider political participation tends to hold across European democracies (Kaase Citation1999; Hooghe and Marien Citation2013). Still, we include additional replication analyses of (more limited) data from 29 European countries. Given these results and the literature, the results of our case can be considered informative for other European democracies.

The set-up of this article also involves two steps that structure the remainder. First, an LCA assesses how activities cluster. Second, the likelihood of citizens belonging to a particular profile is modelled on their resources and political motivations (i.e. trust, efficacy, interest; time, education) using fractional multinomial logit regression (FMLR) models.

Step 1: identifying participation profiles

Political participation?

Political participation research generally uses the traditional distinction between institutional and non-institutional forms of political participation (Ohme et al. Citation2018; Van Deth Citation2014). This conceptualisation, however, does not distinguish between different forms of non-institutional participation and lacks a framework to identify and capture emerging types of such participation. In his operational definition, Van Deth (Citation2014) circumvented this problem and provided us with our starting point. He includes (i) activities that are located within the sphere of the state (e.g. voting, party volunteering, contacting politicians); (ii) acts that are located outside this sphere but still targeting the political arena or a common cause (e.g. signing petitions, joining demonstrations); and (iii) activities located outside the sphere of the state and not targeting the collective level, while still motivated by political intentions (e.g. political consumerism, online commenting).

While Van Deth’s approach provides a demarcation of actions and thereby a frame of understanding, it is still activity-oriented. In line with the current complementary approach, we argue for flipping the perspective: studying how citizens combine different actions to create distinctive political participation profiles. Below, we lay down new theoretical groundwork for doing this, which goes some way to explaining that the same act needs to be interpreted differently depending on the profile it is part of (cf. Alvarez et al. Citation2017; Amna and Ekman Citation2014; Johann Citation2012; Johann et al. Citation2020; Keating and Melis Citation2017; Oser Citation2017; Oser et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Sinclair-Chapman et al. Citation2009; Steenvoorden Citation2018).

Theorising participation profiles

Although explicitly defined participation profiles or references to them are close to non-existent, numerous strands of the literature hint at them, most prominently literature on the political paradox, political transformation, populism and stealth democracy.

The political paradox literature states that citizens who already participate in politics are politically driven and highly likely to engage in emerging forms of political participation as a means of expanding their political toolkit (Kern and Hooghe Citation2018; Marien et al. Citation2010; Schlozman et al. Citation2012). New political instruments do not level the playing field, they argue, but benefit already active citizens. The paradox literature thus implicitly refers to a cluster of citizens who are highly likely to participate in all modes of political participation.

The political transformation literature argues that the decline in electoral participation is being countered by an increase in non-institutional participation (Copeland Citation2014; Dalton Citation2008). This implies two participation profiles: first, people who grew up at a time when voting was considered a duty and are likely to vote in elections and leave politics to their representatives (Blais Citation2000; Van Deth Citation2014). They are unlikely to participate in Van Deth’s targeted and motivational modes. Second, there are those for whom voting is not necessarily a given. Among these, the politically active are the mainstay of the transformation and are particularly likely to take part in newer modes of participation outside the sphere of the state.

Research on populism and populist attitudes stresses anti-elitism and suggests that populist citizens are dissatisfied with the functioning of democracy (Engesser et al. Citation2017; Spruyt et al. Citation2016). Accordingly, it has been argued that they are less likely to vote in elections, but not to be disengaged in general; they prefer direct forms of democracy that empower ‘the people’. These include tools such as referenda (Jacobs et al. Citation2018) and other means of expression, for instance circumventing media elites via online participation (i.e. reacting and commenting on political issues on social media) (Jeroense et al. Citation2021). So a ‘populist participation profile’ entails a lower probability of voting in elections and relatively high participation in referenda and targeted and motivational modes of political participation.

Finally, the stealth democracy literature stresses that most citizens have no desire to participate actively in politics. Instead, they prefer to leave it to elected representatives with whom they only have to bother every few years (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Citation2002; Webb Citation2013). This literature suggests a profile of people likely to participate in first-order (e.g. national) elections but who barely engage in any other mode of political participation.

Whether these four distinct theoretical profiles are borne out empirically is the subject of the remainder of Step 1 below.

Data and methods

Case selection and sample description

The Netherlands presents a fairly typical case, in the Western European context, for the theoretical mechanisms that we are interested in: it has a (relatively strongly) proportional voting system, is a multi-party democracy with non-compulsory voting, and the use of online social media is widespread (Jacobs and Spierings Citation2016). Moreover, both national and local referenda have taken place in the Netherlands. The (corrective) referendum law offers a somewhat stronger incentive for ‘no’ voters to vote in referenda, and parties and actors that want to repeal a law mobilise voters first (see Jacobs et al. Citation2018). For local referenda no such incentive exists. Thus, a wide range of realistic options for participation are available. Additional robustness analyses of fewer items but in more countries align with the results presented below and are given in the online appendices.

Data from the LISS panel are used, including the Dutch National Referendum Research (NRO) (CentERdata Citation2019; Jacobs Citation2018). The third waveFootnote1 of the NRO was conducted during the national referendum on the new law on intelligence and the security services (18 March 2018) and includes electoral participation in different types of elections and referenda, along with digital activities. Items on first- and second-order elections and referenda are present less often, but are pivotal for distinguishing the profiles derived from the literature. Matching the NRO data with the LISS politics and values module gave us access to 12 items in total ().

Table 1. Descriptive statistics political participation items.

Latent class analysis

LCA identifies discrete clusters (‘classes’) of respondents who score similarly on a set of categorical variables (Goodman Citation2007). For every specified class, latent class models return the conditional probabilities of participation in a type of political activity per distinguished profile. These probabilities enable a theoretical interpretation of the different (latent) classes. In addition, the LCA assigns to each individual the probability of being in one of the classes. Based on these, the size of the different classes is estimated.Footnote2

We estimate latent class models in R using the poLCA package (Linzer and Lewis Citation2011) on the 12 given items. To determine the optimal solution, we considered the log-likelihood, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and substantive meaning of the outcomes.

Results: five profiles

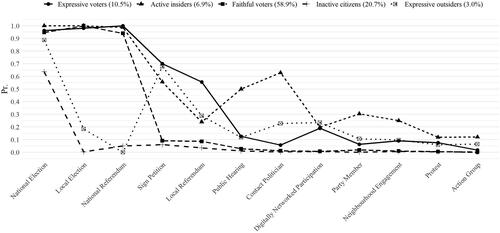

Of the estimated models (see ), we selected the model with five classes (M5) as it has the lowest BIC, and the decrease in log-likelihood flattens in models with more classes (see online appendices). Moreover, the model is theoretically interpretable (although the classes do not simply overlap with those derived from the literature). presents the distilled participation profiles, with the conditional probabilities of participating in an activity on the y-axis. These form the basis of our interpretation below, summarised in our labels.

Figure 1. Conditional probabilities LCA.

Source: CentERdata Citation2019; Jacobs Citation2018.

Table 2. Goodness of fit statistics LCA.

The most prevalent profile (∼58.9%) identifies citizens who are likely to engage in activities that involve a ballot box. Their likelihood of participating in national and local elections and national referendums sits at over 90%, but for all other activities it is below 10% and often close to nil. This profile reflects the dutiful participant profile as proposed by Dalton (Citation2008) in the transformation literature, with arguably a stronger focus on the ballot box. Given the possibility that these respondents might vote out of socialised habit, not normatively experienced duty per se, we label them ‘faithful voters’.

The second most prevalent profile (∼20.7%) shows a relatively low probability of voting in national elections (vis-à-vis the other profiles) and a low likelihood of participating in any other way. We label them ‘inactive citizens’. This profile shares traits with two of the theoretically expected groups: correspondingly, disengaged citizens from the transformation and stealth democracy literature are unlikely to participate in any form of politics other than elections. However, we would expect a higher probability of voting in national or other elections for stealth democrats.

The three further profiles distinguish different groups of relatively active citizens. The first, labelled ‘active insiders’ (∼6.9%), have the highest probability of engaging in almost all modes of participation – particularly in terms of being a party member, contacting a politician and attending public hearings. They are politically highly active and engage to a relatively high degree in activities that directly target representative bodies. This profile fits the ‘political activist’ group from the paradox literature, which expects the same citizens to be involved in most forms of political participation. The nuance here is that for ‘active insiders’, activities located within the system seem most popular, not the relatively new ones.

Next, we find a group (∼3%) that is characterised by a relatively low probability of voting (compared to faithful voters, active insiders and expressive voters), suggesting a greater distance from representative politics. Yet they also show a relatively high likelihood of signing petitions, contacting politicians and engaging in online activities (compared to inactive citizens and faithful voters). What these latter activities share is that they can all be used to express political opinions that are not pre-set or fitting a particular framework. For instance, while contacting a politician is generally seen as a conventional activity, in this profile it makes better sense to see it as more active and expressive. Accordingly, we label members of this profile, who resemble the direct-action-oriented participants from the transformation literature, as ‘expressive outsiders’.

Members of the final profile shows a high probability of voting in any ballot box activity, relatively low probability of engaging in other activities that target government directly, while being relatively likely to sign petitions and use social media politically. This group we label ‘expressive voters’ (∼10.9%). In contrast to the faithful voters, this group is also very likely to participate in local referenda; in contrast to expressive outsiders, they are much more likely to vote; and compared to active insiders they are less active in party politics. This profile resembles the theorised populist profile most closely, given the relatively high probability of participating in referenda, signing petitions and engaging digitally, but without the relatively low probability of voting in first- or second-order elections.

Our interpretation above was grounded in the existing literature on participation and democratic functioning and Van Deth’s (Citation2014) operational definition, and we believe that these two perspectives give a logical explanation for how actions are combined. However, one could argue that these configurations are particular to their context or the items included. Therefore, as a test of tenability beyond our case, we conducted a second analysis based on ESS9 data (for details see online supplementary material). In ESS9, data for nine items are available across 29 countries for 2018 (ESS Round 9: European Social Survey Round 9 Data Citation2018). As these items do not cover referenda or anything other than national first-order elections, the clusters will evidently be different; however, if the results presented above are not idiosyncratic, we should be able to interpret and understand the profiles returned from the ESS in similar ways.

The additional cross-national analyses of 29 countries (for details see the online supplementary materials) show strongly overlapping patterns: (1) a profile of citizens who only vote, and to a lesser degree; these correspond to inactive citizens and faithful voters (in the cross-national data no distinction can be made, as only first-order elections are included); (2) citizens who vote (but slightly less than other groups) and engage in expressive acts outside the system (the ‘expressive outsider’ above); (3) profiles that are distinct from the rest in their likelihood of high participation across the board, but particularly in activities geared towards representative politics. Depending on the statistical choice made, this group splits into two subgroups, but the superset is very similar to that of the ‘active insiders’; and (4) finally we found one to several profiles who all share with the expressive voters the probability that they will vote and engage in expressive acts, but participate less in party activities. The distinction from the expressive outsider is less clear-cut than in the Dutch data, but the core defining action (e.g. voting in referenda) is not present in the cross-national data. Crucially, the core patterns that could be detected with the more limited set of items did surface.

Turning to the theoretical grounding, the LCA clusters we found overlap with the implicit theoretical expectations from the participation and democracy literature, but this overlap is far from complete. Ideas implied in the literature on the political paradox, political transformation, populism and stealth democracy still demand greater empirical and theoretical refinement. To contribute to this further, our next step is to connect these actions to political motivations and resources.

Step 2: political motivations and resources

Theorising belonging to a participation profile

We assumed that citizens participate in politics to exert influence and reach a specific goal (Harris and Gillion Citation2010; Norris Citation2002). Additionally, in line with existing theories, we assume that motivations and resources shape participation (e.g. Norris Citation2002; Verba et al. Citation1995), but our innovation is to link this to our profiles. More specifically, in the remainder of this study we focus on the evaluation of political institutions, the role of political interest and internal efficacy (political motivations), and on time and education as indicators of cognitive abilities and civic skills (resources). By theoretically and empirically linking these to the participation profiles, we (a) increase our understanding of citizens’ participation in representative democratic politics and (b) shed new light on these explanatory factors for political participation. The hypotheses are presented in .

Table 3. Hypotheses.

Motivations

In this study, we consider trust, satisfaction with democracy and external efficacy to all form part of a larger concept that can influence people’s participation, namely the degree to which people hold a positive evaluation of political institutions. For instance, the literature shows that individuals with a high level of political trust are more likely to participate in the political domain, i.e. are more likely to engage in institutional types of participation (Hooghe and Marien Citation2013), and similar arguments have been put forward for satisfaction with democracy and high external efficacy, as those citizens consider the government to be responsive to their demands (Balch Citation1974; Dahlberg et al. Citation2015). Conversely, citizens with a low level of trust are more likely to participate in non-institutional actions, as they have more faith that these will lead to favourable political outcomes.

Applying this logic to the profiles, we expect that those who evaluate political institutions positively are more likely to fit profiles that are geared towards the representative democratic system: active insiders, expressive voters and faithful voters. They might be engaged in activities outside the electoral and party sphere, but not exclusively.Footnote3 However, those individuals who evaluate political institutions negatively are likely to circumvent these institutions in their activities or withdraw completely: expressive outsiders and inactive citizens. The profiles approach thus suggests that signing petitions or engaging in other online political activities are linked to more negative evaluations of political institutions in certain combinations, and positive evaluations in others. A standard approach conflates this, leading to a watered-down overall effect (Hooghe and Marien Citation2013; Kaase Citation1999).

Traditionally, research into political interest argues that political action is preceded by an interest in politics, because interested citizens monitor politics and can better identify potential political acts. Based on this reasoning, politically interested citizens are likely to combine multiple participation modes, although the exact activities might differ. This translates into a higher likelihood of belonging to the active insiders, expressive voters or expressive outsiders. For each of these, some interest in politics is needed to know what is going on and, for instance, whom to contact. Instead, citizens with low political interest are likely to belong to the inactive citizen group. Finally, and pivotally, the literature links political interest unequivocally to voting (e.g. Jacobs and Spierings Citation2010), but it is unlikely that political interest is positively associated with being a faithful voter if we are correct in saying that citizens in this group mainly vote out of a sense of duty or habit.

How internal political efficacy relates to citizens’ participation profile depends on how voters assess the demands being made of them (Gil de Zúñiga et al. Citation2017), which varies across the profiles. Citizens with high internal efficacy feel capable of participating politically and are more likely to belong to a profile combining multiple (complex) modes of participation. Therefore, efficacy is likely to be connected to active insiders and expressive outsiders, even though the two groups combine rather different actions (which might obscure efficacy’s impact when using standard act-based models).

The association between internal political efficacy and the other profiles is expected to be less profound, but not absent. Voting in second-order elections, as the expressive insiders do, is certainly more demanding than only voting in first-order elections. Moreover, if our interpretation of the faithful voters is correct, internal efficacy should not stimulate voting, as duty is the main driver for this group regardless of feeling efficacious. Lastly, when citizens feel that they are incapable of participating, it is likely that they disengage from politics completely, increasing the likelihood of belonging to the inactive citizens group.

Resources

Next to motivations, previous research shows that resources are an important enabler for political participation: citizens need the skills and the time to participate in politics. We expect these enablers to become manifest in educational level and (inverse) working and care-taking time (see Brady et al. Citation1995; Schlozman et al. Citation2012). It is the effects of these that we will first translate to our profiles, after which we will reflect upon the interrelated impact of resources and motivations.

The core logic linking resources to activity profiles is that, to mix different and more intensive activities, individuals tend to need more resources at their disposal. In terms of time, the profiles of expressive outsiders and active insiders are particularly demanding as they span activities from all modes of politics and require commitment and intensive involvement. Having less time to spare steers people away from these more intensive profiles and towards those that involve incidental acts like voting or responding to a social media post (i.e. the expressive voters). At the same time, for the profiles of faithful voters and inactive citizens, we would argue that time is not a factor, as the reasons for (non-)participation are not expected to be grounded in considerations such as this.

In terms of skills (education), it is mainly the active insiders, expressive voters and expressive outsiders who have ‘costly’ profiles, as these demand a mix of actions for which (some more than others) they need knowledge and civic skills. In contrast, this is evidently not the case for inactive citizens: the more skilled a person is, the more likely they are to engage in one way or another. The exception, however, seems to be voting in first-order elections (i.e. our faithful voters) out a sense of habit or duty, which is an act that requires very little in terms of civic skill and is unlikely to be influenced by these resources (see Blais Citation2000).

Interrelated conditions

The discussion about resources and faithful voters has already intimated that motivations and resources might not be completely unconnected. For instance, as suggested before (Christensen Citation2016; Hooghe and Marien Citation2013), a positive or negative evaluation of political institutions is more likely to be related to participation when someone feels able, has the time or has the cognitive skills to get involved (Hernandez and Ares Citation2018).

The core logic we want to put forward is that for people to engage in politics, the combination of the opportunity to do so and the will to do so might be of particular importance. Without wanting to suggest determinism, these two core elements can be considered independently necessary and jointly sufficient. With the resources but with little political will, a person is less likely to become active. For instance, if the will consists only of a sense of duty but not clear political will (i.e. political evaluation or interest), resources are less likely to matter. Conversely, if a person has civic skills, being more politically interested is likely to bring higher returns, as that person can more easily translate this interest to action.

Above, we phrased the core logic on cojoined effects in terms of opportunity and will. Here we deviate from the standard distinction between resources and motivations (e.g. Norris Citation2002). Given the logic of our argument, internal political efficacy is much closer to resources than to the other two political motivations. Consequently, we focus on how spare time, education, and internal efficacy strengthen the effect of positive evaluation of politics and political interest on belonging to a profile as the starting point for this last analytical step.

As summarised in , we argue that a strengthening moderation is most likely to be found among expressive outsiders, expressive voters and active insiders. These three profiles involve multiple and considerable resources as well as being grounded in either positive (e.g. active insiders) or negative (e.g. expressive outsiders) political motivations. In other words, these three profiles are rooted in both sets of factors, and thus we expect a strengthening moderation.

For the faithful voters and inactive citizens, we do not expect a strengthening (or for that matter weakening) impact, as people are in any case unlikely to participate (inactive citizens) or their participation is not expected to be driven by interest or political motivation (faithful voters). In other words, the will barely exists, so there is little to trigger the use of (self-perceived) capacities or resources.

Methods

Fractional multinomial logistic regression

In order to test our hypotheses, we use FMLR, with respondents’ probabilities for belonging to the LCA’s profiles as dependent variables (Papke and Wooldridge Citation1996). About 75% of the respondents have a posterior class probability >0.8 for one specific class; and 85% >0.7. This deviates from the more common, simpler three-step method: LCA estimation > classification > multinomial logit regression (Vermunt Citation2010). As discussed by Vermunt (Citation2010), classifying respondents into one of the (here five) groups leads to a downward bias in standard errors, which we can partly counter by using FMLR (i.e. we model the variation in probability to belong to a profile explicitly). Still, standard errors might be slightly deflated, which demands caution in drawing strict conclusions on effects that border statistical significance (also acknowledging that the set confidence threshold is arbitrary).

Based on the FMLR models, we calculated average marginal effects (AMEs), which are most directly and easily interpreted. (These are presented below in ; the underlying FMLR models form part of the online supplementary material. For the interactions, we present the marginal effect plots in the online appendices.) After listwise deletion of missing values, 1777 cases remain of the 2219 cases included in the LCA.

Table 5. AME of FMLR on participation profiles.

Measures

provides descriptive statistics of the political motivation, resource and control variables. Positive evaluation of political institutions was measured using six survey items covering political trust, external efficacy and satisfaction with democracy. A factor analysis suggested that these items tap into one latent factor. We used the extracted factor scores. Political interest was measured as a standard three-category variable, and for internal political efficacy we extracted factor scores based on three standard internal efficacy items, tapping one factor. For details, see the online supplementary material.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics explanatory variables (N = 1777).

Education was included as the highest attained level of education in six categories, each given separately to capture non-linearities. Finally, time constraints were calculated by adding the hours per week that respondents reported spending on education, work and informal care. A lower score thus indicated more available time. Again, to capture non-linearities these were given in five categories (see ).

The models control for the presence of children in the household, marital status, age (self-reported), self-reported gender, employment and income (ln).Footnote4

Results

The results of the FMLR’s AMEs are presented in (main effects), and we discuss them in two sections. First, we discuss them per explanatory factor (i.e. hypothesis). Second, we reflect on the different profiles and their relation to their antecedents from our FMLR models.

Political motivations and resources

Regarding motivations, most hypotheses find support (H1c–H1e; H2a–H2e; H3a–H3c, H3e). A more positive evaluation of political institutions was positively associated with faithful citizens and negatively with disengaged citizens or transformers. The absence of an effect for expressive voters and active insiders suggests that the more intensive profiles can be fuelled by a better evaluation of political institutions, but also by a worse evaluation and need for change.

As expected, the more politically interested are more likely to belong to an active or expressive profile and less likely to be inactive. Political interest is not related to being a faithful voter. The relationship between interest and voting in standard action-based models might be diluted as, for many voters, habit or duty overwrites interest.

Internal political efficacy is positively associated with active insiders and expressive voters and negatively with faithful voters and inactive citizens. Surprisingly, no (positive) relationship with being an expressive outsider was found. Thus internal efficacy, it seems, steers towards system-focused participation.

On resources, the picture is more complex. While there is fairly definite support for H4a–H4c, H4e and H5b–H5c, results for H4d and H5e are uncertain and H5a is clearly refuted. Higher education relates positively to all three of the active or expressive profiles and negatively to inactivity, but for expressive outsiders the relationship is weaker and less linear: in particular, those with a middling level of education can be found in this profile. It seems that education feeds into political activities, but an intermediate level of education is linked to participation both within and outside the system, whereas higher education is connected more to the former.

Finally, time constraints do not seem to be constraints per se: those with the greatest constraints are also most likely to be active citizens (the most engaged profile) or expressive voters, which are the two profiles centred around relatively high activity, particularly in representative politics. It seems that those with least time are also those who still find ways to become politically active in representative politics. For the other profiles, time constraints have no clear impact; overall, this undermines the time-constraint logic.

We present the results of the moderation analyses in the online materials, because, by and large, the literature-based expectations we formulated are not supported (H6a–H6e). As the figures show, there is barely any level of education, internal efficacy or time for which the AMEs consistently and systematically deviate from the mean predicted probability of political interest or of a positive evaluation of political institutions. For instance, the time-by-interest moderation for active insiders shows that citizens with a higher level of interest are more likely to belong to this group (top left panel; page 30 of the online supplementary materials), but the confidence intervals for being highly interested per time-constraint group overlap considerably. A few statistically significant results were found, but these do not consistently point in the expected directions. For instance, and particularly, the roles of education and political interest in precluding entry to the inactive citizens groups bolster each other.

One explanation for the absence of the expected effects might be that the profiles for which we expected moderations are rather small. However, the probability of being an expressive voter still amounts to the equivalent of around 200 cases. Moreover, not only is statistical significance absent; the expected pattern is as well. Actually, the profiles approach considers specific activities in the context of a repertoire that might account for moderation results found in activities-based studies, but more research on this is needed.

Five participation profiles

The combined information on the participation profiles and their antecedents now enables us to characterise and distinguish the clusters of individuals that belong to these five profiles.

First, active insiders and expressive voters are likely to be similar individuals: those who are interested in politics, consider themselves capable and are highly educated are more likely to belong to one of these very active classes. However, their evaluation of political institutions does not seem to relate to these profiles; both satisfaction and dissatisfaction with current politics seem to fuel their involvement. A main difference between the two groups is that those with greater time constraints are more likely to be part of the expressive voter group, which features less intensive activities. Differences for our demographic control variables were also found, suggesting that other norms or circumstances play a role in steering to certain combinations of activities. In particular, men and unmarried individuals are more likely to be active insiders, which seems to align with gendered notions of the core of the political sphere being masculine and badly attuned to family responsibilities (e.g. Byrne and Theakston Citation2016; Dahlerup and Leyenaar Citation2013).

The results for expressive outsiders show no clear relation to resources. However, they are negatively linked to the evaluation of political institutions; the positive link to political interest is borderline statistically significant. Additionally, the demographic controls show that younger people are more likely to be expressive outsiders. Altogether, the archetypal expressive outsider seems to be a younger citizen who is unhappy with the current system but still has some interest in politics, which manifests itself in expressive extra-institutional activities.

In contract to these active classes, we find a sizeable group (about one in five) of inactive citizens. Less politically interested citizens, those who evaluate political institutions negatively, and those who are less well-educated are more likely to belong to this group, particularly those who exhibit several of these characteristics. Across the board, this group seems to be disconnected from politics, and, when compared with the two most active groups above, they demonstrate a clear educational inequality: those with a higher level of education press their concerns more. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the older individuals are, the less likely they are to belong to this profile. It seems that older citizens are socialised more to trust authority and to vote, and thus fit our final profile, discussed below.

The largest group in our sample is the faithful voters: those who show up on election day, but do no more. In particular, citizens who do not feel capable of playing an active role and those who still evaluate political institutions positively are most likely to belong to this profile. Education and time constraints play no role, but citizens who are married, have children, receive a higher income and are older are more likely to be faithful voters. By and large, the archetype here seems to be a citizen who is relatively secure and (perhaps as a result of this) does not see a political role for themselves other than habitually going to the voting booth.

Conclusion and discussion

This study set out to find an answer to two questions: What different political participation profiles can we identify? and To what extent can different resources and political motivations explain citizens’ participation profiles? These were intended to be a first step and an invitation for future political participation profile studies to help further understanding of the forms, causes and implications of political participation in contemporary democracies.

The results identify five different participation profiles, each with a unique repertoire with respect to the activities that they combine. These findings shed new light on different theories regarding the state of our democracy. Most crucially, they show (a) that empirical reality reflects some of the theorised profiles, particularly from the transformation literature (Copeland Citation2014; Dalton Citation2008) and participation paradox (Kern and Hooghe Citation2018; Marien et al. Citation2010; Schlozman et al. Citation2012), but even these theories require some updating to fit our empirical results fully; and (b) that each of these theorised groups only relates to some of the people, implying that different frameworks need to be combined in order to understand both levels of political participation and their implications for democracy.

Moreover, combining our activity-rich data with the profiles approach, and linking this to the motivations and resources explanations has shown how motivations and resources can give rather divergent results. For instance, negative evaluations of the political system lead some people to participate outside it and to general disengagement, the core difference being their level of political interest. Also, higher education is related to expressive activities outside the system among the people who are engaged in insider acts too, but not to expressive activities among people who are mainly active outside the system; this education effect is diluted in a more standard act-based approach.

Further, some profiles resemble one another in terms of their relationship with political motivations and resources (e.g. ‘active insiders’ and ‘expressive voters’), while their participation profiles show distinct differences. In itself, this multi-finality is an important empirical observation, but it also indicates that distinguishing antecedents are missing in the resources-and-motivations model. Maybe the third element of the civic voluntarism model (see Verba et al. Citation1995), mobilisation, can play a role in explaining this difference, and demographic differences could be explored that would give substantive explanations, such as gendered constraints and norms.

Returning to the state of democratic politics in Western Europe, our results provide at least four considerations. First, the vast majority of citizens (∼80%) are either disengaged from politics or seem to vote out of a sense of habit or duty. Unconventional, online and direct modes of political participation have not pulled these people in. Second, the least active class (people who do not vote or do so irregularly), do not seem to refrain because they think things are going well, as suggested in the stealth democracy literature (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Citation2002). Third, our results confirm an educational political-participation divide (see Marien et al. Citation2010). We found roughly a fifth of people at either extreme. Citizens with fewer resources are far more likely to be disengaged from politics across the board, not just institutional politics. Finally, older citizens are more likely to be faithful voters, and younger citizens more likely to be inactive citizens and expressive outsiders. If this is a generational (rather than age) effect, citizenries’ political activities will decrease in the future (ceteris paribus) due to generational replacement.

Our results pertain to the Dutch case and we hope that LCA on a wide variety of political acts will be conducted more broadly in the future. For now, however, our robustness analyses of 29 countries suggest that the clustering does travel, but that the sizes of clusters might differ, begging for further theorisation. Also, Van Deth’s (Citation2014) demarcation can be used to expand definitions of political acts further to see if the clusters still hold up. Finally, LCA is a relatively new technique and still in development. Some developments have not yet been incorporated in opensource software like R, which would allow for broader replication and robustness.

ORCID details

Thijmen Jeroense https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0911-6486

Niels Spierings https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3116-3262.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (2.6 MB)Acknowledgements

We want to thank the seminar attendees at Radboud Social Cultural Research for their feedback and valuable comments. We would also like to thank the editors at WEP and the anonymous reviewers for their sharp, constructive comments and feedback. These greatly improved our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The datafiles that are used for this study are available after registration at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ and https://www.lissdata.nl/. All code, with annotations, that was used for the analyses can be found at the OSF repository: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/YNBMV.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thijmen Jeroense

Thijmen Jeroense is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology/ICS, Radboud University Nijmegen. His research focus is on political participation, public opinion dynamics and offline political discussion networks. He has published in European Political Science. [[email protected]]

Niels Spierings

Niels Spierings is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology/ICS, Radboud University. His research is centred on questions of inclusion and exclusion, focussing on, among other things, political participation, populism, social media, public opinion and gender inequality. On these topics he has published in journals such as Political Behavior, West European Politics, New Media & Society, Electoral Studies, Information, Communication & Society, and European Political Science. He has also published a monograph on politics and social media with Palgrave. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Completed: 78.7% of 2838 panel members.

2 Class size determined by modal assignment (hard partitioning) (Vermunt 2010).

3 Were we to consider the faithful voter as purely driven by a sense of duty, it could be argued that evaluation of the system does not matter for them. However, as we have argued that both habit and duty are potentially involved, negative evaluation might discourage the people in this group who vote out of habit, not duty.

4 Missing values imputed by multiple imputation.

References

- Alvarez, R. Michael, Ines Levin, and Lucas Nunez (2017). ‘The Four Faces of Political Participation in Argentina: Using Latent Class Analysis to Study Political Behavior’, The Journal of Politics, 79:4, 1386–402.

- Amna, Erik, and Joakim Ekman (2014). ‘Standby Citizens: Diverse Faces of Political Passivity’, European Political Science Review, 6:2, 261–81.

- Arendt, Hannah (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Balch, George (1974). ‘Multiple Indicators in Survey Research: The Concept Sense of Political Efficacy’, Political Methodology, 1:2, 1–43.

- Blais, Andre (2000). To Vote or Not to Vote? The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Brady, Henry, Sidney Verba, and Kay Schlozman (1995). ‘Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation’, American Political Science Review, 89:2, 271–94.

- Byrne, Christopher, and Kevin Theakston (2016). ‘Leaving the House: The Experience of Former Members of Parliament Who Left the House of Commons in 2010’, Parliamentary Affairs, 69:3, 686–707.

- CentERdata (2019). LISS Core Study: Politics and Values [Data Files and Codebooks]. Retrieved from

- Christensen, Henrik (2016). ‘All the Same?’, Comparative European Politics, 14:6, 781–801.

- Copeland, Lauren (2014). ‘Conceptualizing Political Consumerism: How Citizenship Norms Differentiate Boycotting from Buycotting’, Political Studies, 62:1_suppl, 172–86.

- Dahlberg, Stefan, Jonas Linde, and Sören Holmberg (2015). ‘Democratic Discontent in Old and New Democracies: Assessing the Importance of Democratic Input and Governmental Output’, Political Studies, 63:1_suppl, 18–37.

- Dahlerup, Drude, and Monique Leyenaar (2013). Breaking Male Dominance in Old Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, Russel (2008). ‘Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation’, Political Studies, 56:1, 76–98.

- Engesser, Sven, Nicole Ernst, Frank Esser, and Florin Büchel (2017). ‘Populism and Social Media: How Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology’, Information, Communication & Society, 20:8, 1109–26.

- ESS Round 9: European Social Survey Round 9 Data (2018). Data File Edition 3.1. NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and Distributor of ESS Data for ESS ERIC.

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Trevor Diehl, and Alberto Ardévol-Abreu (2017). ‘Internal, External, and Government Political Efficacy: Effects on News Use, Discussion, and Political Participation’, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61:3, 574–96.

- Goodman, Leo (2007). ‘On the Assignment of Individuals to Latent Classes’, Sociological Methodology, 37:1, 1–22.

- Harris, Frederick C., and Daniel Gillion (2010). ‘Expanding the Possibilities: Reconceptualizing Political Participation as a Toolbox’, in Jan Leighley (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of American Elections and Political Behaviour. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hernandez, Enrique, and Macarena Ares (2018). ‘Evaluations of the Quality of the Representative Channel and Unequal Participation’, Comparative European Politics, 16:3, 351–84.

- Hibbing, John, and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse (2002). Stealth Democracy: American’s Beliefs about How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, Marc, and Sofie Marien (2013). ‘A Comparative Analysis of the Relation between Political Trust and Forms of Political Participation in Europe’, European Societies, 15:1, 131–52.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Gabriella Catterberg (2002). ‘Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43:3-5, 300–16.

- Jeroense, Thijmen, Jorrit Luimers, Kristof Jacbos, and Niels Spierings (2021). ‘Political Social Media Use and Its Linkage to Populist and Postmaterialist Attitudes and Vote Intention in The Netherlands’, European Political Science, 1–22. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00306-6

- Jacobs, K. (2018). WIV Referendum 2018: Third Measurement [Data File and Codebook].

- Jacobs, Kristof, Agnes Akkerman, and Andrej Zaslove (2018). ‘The Voice of Populist People? Referendum Preferences, Practices and Populist Attitudes’, Acta Politica, 53:4, 517–41.

- Jacobs, Kristof, and Niels Spierings (2010). ‘District Magnitude and Voter Turnout a Multi-Level Analysis of Self-Reported Voting in the 32 Dominican Republic Districts’, Electoral Studies, 29:4, 704–18.

- Jacobs, Kristof, and Niels Spierings (2016). Social Media, Parties, and Political Inequalities. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Johann, David (2012). ‘Specific Political Knowledge and Citizens’ Participation’, Acta Politica, 47:1, 42–66.

- Johann, David, Markus Steinbrecher, and Kathrin Thomas (2020). ‘Channels of Participation: Political Participant Types and Personality’, PLoS One, 15:10, e0240671.

- Kaase, Max (1999). ‘Interpersonal Trust, Political Trust and Non‐Institutionalised Political Participation in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 22:3, 1–21.

- Keating, Avril, and Gabriealla Melis (2017). ‘Social Media and Youth Political Engagement: Preaching to the Converted or Providing a New Voice for Youth?’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19:4, 877–94.

- Kern, Anna, and Marc Hooghe (2018). ‘The Eeffect of Direct Democracy in the Social Stratification of Political Participation: Inequality in Democratic Fatique?’, Comparative European Politics, 16:4, 724–44.

- Linzer, Drew, and Jeffrey Lewis (2011). ‘poLCA: An R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis’, Journal of Statistical Software, 42:10, 1–29.

- Marien, Sofie, Marc Hooghe, and Ellen Quintelier (2010). ‘Inequalities in Non-Institutionalised Forms of Political Participation: A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries’, Political Studies, 58:1, 187–213.

- Norris, Pippa (2002). Democratic Phoenix. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ohme, Jakob, Claes H. de Vreese, and Erik Albaek (2018). ‘From Theory to Practice: How to Apply Van Deth’s Conceptual Map in Empirical Political Participation Research’, Acta Politica, 53:3, 367–90.

- Oser, Jennifer (2017). ‘Assessing How Participators Combine Acts in Their "Political Tool Kits": A Person-Centered Measurement Approach for Analyzing Citizen Participation’, Social Indicators Research, 133:1, 235–58.

- Oser, Jennifer (2021). ‘Protest as One Political Act in Individuals’ Participation Repertoires: Latent Class Analysis and Political Participant Types’, American Behavorial Scientist. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211021633

- Oser, Jennifer, Marc Hooghe, and Sofie Marien (2013). ‘Is Online Participation Distinct from Offline Participation? A Latent Class Analysis of Participation Types and Their Stratification’, Political Research Quarterly, 66:1, 91–101.

- Oser, Jennifer, Jan Leighley, and Kenneth Winneg (2014). ‘Participation, Online and Otherwise: What’s the Difference for Policy Preferences?’, Social Science Quarterly, 95:5, 1259–77.

- Papke, Leslie, and Jeffrey Wooldridge (1996). ‘Econometric Methods for Fractional Responde Variables with an Application to 401(K) Plan Participation Rates’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11:6, 619–32.

- Schlozman, Kay, Sidney Verba, and Henry Brady (2012). The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sinclair-Chapman, Valeria, Robert Walker, and Daniel Gillion (2009). ‘Unpacking Civic Participation: Analyzing Trends in Black [and White] Participation over Time’, Electoral Studies, 28:4, 550–61.

- Spruyt, Bram, Gil Keppens, and Filip Van Droogenbroeck (2016). ‘Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?’, Political Research Quarterly, 69:2, 335–46.

- Steenvoorden, Eefje (2018). ‘One of a Kind, or All of One Kind? Groups of Political Participants and Their Distinctive Outlook on Society’, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29:4, 740–55.

- Theocharis, Yannis, and Jan Van Deth (2018). ‘The Continuous Expansion of Citizen Participation: A New Taxonomy’, European Political Science Review, 10:1, 139–63.

- Van Deth, Jan (2014). ‘A Conceptual Map of Political Participation’, Acta Politica, 49:3, 349–67.

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Schlozman, and Henry Brady (1995). Voice and Equality. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Vermunt, Jeroen (2010). ‘Latent Class Modeling with Covariates: Two Improved Three-Step Approaches’, Political Analysis, 18:4, 450–69.

- Webb, Paul (2013). ‘Who Is Willing to Participate? Dissatisfied Democrats, Stealth Democrats and Populists in the United Kingdom’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:6, 747–72.