Abstract

Designing and evaluating health professions educational programs require a range of skills in a rapidly changing educational and healthcare environment. Not all program directors possess all the required leadership skills. In this twelve tips article, we describe a systematic approach to effectively address the complexity facing program leadership, implement robust programs and meaningfully evaluate their impact. They also offer a roadmap for managing diverse stakeholders with often competing demands. The tips are categorized under three domains: Planning, Initial Implementation, and Monitoring. Specific recommendations are provided on addressing context, organizational culture, and key relationships along with practical techniques adapted from continuous quality improvement programs. An outcomes-based approach ensures that program leaders balance competing demands. The tips provide a structure for educational leaders worldwide to reflect on what is feasible in their own context, understand and address complexities in program design and evaluation, regardless of the resources at their disposal.

Introduction

Worldwide, health professions education (HPEd) has undergone a significant transformation during the latter part of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first century (Frenk et al. Citation2010). In recent years, there has been a growth in the number of health professionals pursuing advanced training in education through Masters programs (Cohen et al. Citation2005; Tekian and Artino Citation2013; Tekian and Taylor Citation2017). Many graduates of Masters in Health Professions Education programs have, or are preparing for, educational leadership roles. In these roles, they address instructional and assessment issues, overcome organizational barriers, and manage change within their respective fields. They strive to make positive contributions to educational priorities at their institutions and/or professional organizations, and fill knowledge gaps that can be shared globally.

With today’s emphasis on outcomes and systematic program evaluation, comparison against benchmarks and continuous quality improvement (CQI) are essential to defining and measuring success. CQI emphasizes self-reflection, assessing needs and gaps, using data, inclusiveness of participants, and ongoing willingness to improve processes and outcomes (Hogg and Hogg Citation1995; The Health Foundation Citation2012; Ham et al. Citation2016). Academic leaders recognize the need for engaging an interprofessional team, implementation with hard outcomes in mind, rigorous program evaluation and scholarship. In addition, guidance and teamwork are required to meet today’s academic and accreditation standards, expectations from various professions, and the demands of society. Information from program evaluation activities provides the impetus for major and/or minor changes necessary to maintain a high-quality curriculum to meet numerous, evolving demands.

For program leaders looking to design HPEd programs, we describe a systematic framework to address the challenges of planning, implementing, and evaluating such programs. The tips are designed to be consistent with the World Federation for Medical Education’s Global Standards for Quality Improvement in Master’s Degrees in Medical and Health Professions Education (Tekian and Taylor Citation2017; World Federation of Medical Education Citation2017). They emphasize the need to interact regularly, acknowledge and meet the goals of various and diverse stakeholders (e.g. current and prospective students, faculty, administrative staff, the broad educational community, internal and external funding sources, professional organizations, publications, accrediting organizations, alumni, sponsors and current or future employers of graduates).

HPEd is composed of complex systems with diverse interacting components – the “whole” being greater than the sum of the parts, inherent and expected ambiguity, and substantial uncertainty. Messy, non-linear relationships among variables occur in overlapping contexts (Frye and Hemmer Citation2012). These inherent qualities require application of complexity science concepts in which dynamics and relationships are the focus (rather than objects) (Mennin Citation2010). The following twelve tips provide a practical approach for HPEd program leaders to successfully address implicit and explicit challenges inherent within complex systems. Frye and Hemmer describe program evaluation models and frameworks for addressing the multiple interactions and complexities of educational programs in AMEE Guide No. 67 (Frye and Hemmer Citation2012). Additionally, we discuss briefly how these tips address some of the key tenets of complexity theory (Mennin Citation2013).

The 12 Tips are categorized under three domains: Planning, Initial Implementation, and Monitoring

Planning

Tip 1

Identify overlapping and diverging interests of various stakeholders

Stakeholders have different roles and priorities that can be complementary or competing even within a group. They can be exceedingly challenging for program leaders to engage and manage. The following recommendations are a synthesis from several sources (Rea and Kerzner Citation1997; Rossi et al. Citation1999; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2017). The program leader should convene a core team with primary responsibility for program evaluation and engaging a broad spectrum of stakeholders. The core team should carry out the following tasks: (1) identify stakeholders based on their roles (e.g. those involved in operations, those who will use the results, and those affected by the program) including any major subgroups within a stakeholder group; (2) list activities and outcomes that matter most to each of the stakeholders; (3) create a plan to engage the stakeholders in two-way/multi-way communications that takes into account a simplified framework for program evaluation: starting context, planned process, planned outcomes, emergent (unplanned) process, emergent (unplanned) outcomes, and ending context (Haji et al. Citation2013); (4) utilize individual core team members to interact with specific stakeholders about content generated in the prior three steps; (5) incorporate feedback from the prior steps and develop a revised plan taking into account what is feasible, who can advocate, who can fund, and who can lend credibility; (6) summarize the stakeholder analysis and communication plan to ensure that all members of the core team are on board. Sometimes these planning activities uncover some of the shortfalls of HPEd program leaders. Self-awareness and honest assessment are essential for HPEd program sponsors and stakeholders in order to create the substrate for Tip 2.

Tip 2

Prioritize stakeholder interests, establish expectations and timelines

All program leaders have high aspirations and aim to design the ideal program. However, they are faced with the realities of numerous challenges and constraints during actual implementation. Prioritization of program elements and tasks often occurs implicitly or “by default” based on what does/does not get done. However, it is important to explicitly go through a prioritization process that shows the choices and tradeoffs so that expectations of various stakeholders can be managed effectively (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2017). In many cases, it could come down to what can be done now vs. in the future. This process also provides a mechanism for identifying where the resource shortfalls are driving choices so that resources can be obtained or reallocated (e.g. “buy-out” time from other tasks, additional part-time staff, etc.). This prioritization process can occur within the core team or between the core team and other stakeholders (e.g. administrative leadership). This is the step that requires prioritization of leadership skill building (Tekian and Taylor Citation2017) if a gap was identified in the prior planning activities. Once the priorities and scope are defined, the rationale for the choices and tradeoffs can be communicated more broadly so that stakeholder consensus (“I can live with” even if I don’t fully “buy in”) can be obtained. This final step can be very difficult because of internal politics and relative influence for securing resources. Making the tradeoffs explicit may be painful in the short run; however, doing so will likely lead to greater satisfaction of more stakeholders in the longer run because assumptions and disagreements can be handled directly.

Tip 3

Assess organizational climate for a continuous quality improvement mind-set

A CQI mind-set is essential for educational leaders striving to continually improve their programs and work within the context of multiple programs. Application of the CQI principles of self-reflection, inclusiveness, data-based decision-making, and ongoing persistence to improve will support working in a cooperative, “we’re all in this together” manner rather than a criticism-based, academic jousting style (Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). While health care professionals are increasingly exposed to CQI training in their respective professional education (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Citation2017), they may be unfamiliar in applying these principles to educational situations. Identifying strengths and gaps in CQI and implementation science skills can also help set up mentor–mentee pairs within the program evaluation work groups. Such mentoring can effectively utilize strengths while facilitating cooperation. The rapid expansion of implementation science efforts has fostered more capabilities for mentoring in more individuals that can be accessed accordingly (Nakanjako et al. Citation2015; Chambers et al. Citation2017).

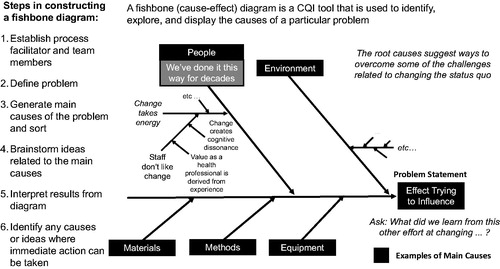

displays a useful CQI tool, the fishbone diagram, for identifying, exploring, and displaying causes of a particular situation or problem (Beaudry Citation2013; Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). In a fishbone diagram, the effect or problem is listed on the right and the main causes with related ideas are listed on the left. To determine the root causes using a structured approach, exploration of organizational culture based on behaviors, espoused values, and basic underlying assumptions can be beneficial, especially when the members of the organization utilize group knowledge of the process (Schein Citation2017). It also increases group knowledge by helping everyone learn more about the factors and how they relate. An example of effective application of a fishbone diagram relates to the beliefs of team members that the status quo must be maintained with resulting resistance to change. Underlying such resistance may be the belief that their own expertise and status are based on experiences tied to the existing system, and disruption of this system creates cognitive dissonance and loss of own validity (e.g. the effectiveness of traditional lectures).

Tip 4

Explore implicit organizational assumptions, choices, and make them explicit

The efforts during Step 3 will bring a number of implicit assumptions that underlie disagreements to the surface, and a variety of approaches can be used to address them. Some might favor an approach where complex interactions are reduced to the sum of the constituent parts in order to render them easier to study (scientific reductionism, Frye and Hemmer Citation2012). Others might recognize how change in one part affects other parts and the whole system but not know how to work with this concept in practice (applications of systems theory, Frye and Hemmer Citation2012). Yet others might readily accept that the messiness and uncertainty associated with the abstract idea that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts (implications of complexity theory). An important component of successfully navigating such discussions is respectful interactions about various viewpoints including respect for the creative process. Framing this phase as an expansive brainstorming phase that needs to be followed by a contraction phase guided by current constraints can enhance team buy-in and inform resource allocations for future efforts. Taking time to do this step can uncover shared “interests” that can be used to achieve consensus rather than focus on “positions” that involve “winners and losers” (Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). Describing viewpoints as trying to make sense of inherent non-linear recursive relationships, interactions, and interdependencies among multiple, diverse elements associated with HPEd and health care itself can offer a path to forge a collective, mutually agreed upon plan to proceed (Mennin Citation2013). “Shared interests” puts the focus on relationships and interdependencies which are focal elements for complexity theory along with the emergent properties of a system (Mennin Citation2013), the system in which all participate.

Tip 5

Identify “need-to-have” vs. “nice-to-have” tasks for various purposes and audiences

Dividing tasks into two groups: “Need to Have” and “Nice to Have” will generate a list of tasks that are feasible and those that can be omitted in the current cycle of activities, thus raising challenging tradeoffs. It is important for program leaders to reflect on the extent to which important outcomes will change what tasks they would carry out immediately vs. what would occur more long-term (Creswell Citation2014). It also provides a way of revisiting the stakeholder analysis and confirming that stakeholder considerations are aligned as much as possible with resource allocations.

Tip 6

Use academic cycles to access resources and create deliverable outcomes

Academic cycles (educational, budget, assessment, accreditation, etc.) and demands tied to milestone events in the academic calendar drive a lot of what program leaders need to do and when they do it. Goals not fulfilled due to expected and unanticipated demands related to these cycles can impact morale of leaders and stakeholders. Sorting through what tasks must be accomplished in what timeframe can help guide the leadership to identify when things are starting to go awry before they reach a crisis/failure point. Also, student resources (e.g. pursuing an independent study course, elective courses at other institutions, or an offsite teaching or research rotation) can be better activated by explicitly including them up front in the planning of program operations. Getting buy-in about the importance of meeting interim outcomes is important; alternatively, they provide a way of collectively adjusting final goals when interim outcomes are not met. Linking individual and team performance metrics will help so that individuals know that these tasks will be counted toward their job performance metrics (Fallon and Zgodzinski Citation2012). Setting aside time for leadership skill building that coincides with academic calendars is another way to enable improvement of HPEd program leaders’ capabilities for directing and managing an effective program.

Tip 7

Anticipate future needs for accreditation, reporting, etc

Accreditation and internal organizational reviews that have a long cycle time between milestone outputs can be challenging – especially ones that are expected to be data rich. Making a list of these upfront is helpful. If data requirements for accreditation and other reviews are planned for explicitly, they can be built into the “need to haves.” In some cases, it may make sense to pilot test data collection on a small scale first, then revise and roll out more broadly. Planning in advance can enable pilot assessments that will improve the quality of the data collected and the experience of team members (Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). Small-scale pilots also demonstrate a CQI mind-set (PDSA cycles – Plan, Do, Study, Act) and can facilitate the evolution to more appropriate (and extensive) quantitative and qualitative data collection (Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). Barzansky et al. (Citation2015) described the intersection of CQI and accreditation systems in the US, Canada, Korea, and Taiwan by noting how interim review of compliance with accreditation standards can support a culture of CQI.

Initial implementation

Tip 8

Assemble team and consider their competing demands up front

Identifying individuals with the necessary skills and available time can be difficult. Holding brainstorming sessions up-front with larger groups of individuals can help leaders get acquainted with individuals with interest, relevant skills, and enthusiasm for the project. Regular meetings with interim outcomes explicitly noted in meeting agendas and minutes can go a long way to addressing competing demands for time. Different team members may have more or less to do at different times and these notes ensure that all are aware of how well the team is accomplishing what it needs to do. This approach will also enable leaders to flag items that are falling behind and plan accordingly with the team and other stakeholders (Shi and Johnson Citation2014). When unexpected circumstances arise, all will have a shared understanding of where the entire project is in terms of completed items and gaps – thereby enabling more constructive actions related to how to handle the exogenous events that often occur.

Tip 9

Work with the team to build a spectrum of skills for a variety of program activities

Addressing team members’ strengths and weaknesses can be one of the most time consuming activities for a leader (including addressing his/her own shortfalls). Enabling all team members to maximize their strengths supports productivity (Rath Citation2007) and provides a pathway for developing new skills – as long as those involved agree that this skill development is worthwhile. Organizational climate, realistic goal setting, and effectiveness of annual performance reviews are essential to having this occur in a fair, feasible way (Shi and Johnson Citation2014). If required elements are not in place (per Tip 3), then it is important to start on a small scale and discern what is working and what is not working. A mentor–mentee scenario is often helpful – especially when each individual team member can have at least one mentor role and one mentee role for different tasks (Fallon and Zgodzinski Citation2012).

Tip 10

Establish processes to support conflict management

Conflict can lead to constructive growth or harmful dynamics. Managing conflict effectively increases the chances that disagreements related to ideas, perspectives, priorities, preferences, beliefs, values, and goals lead to growth, productivity, and commitment. The leader should establish a safe environment for handling disagreements by acknowledging them openly and setting aside time regularly to identify and discuss the various interests underlying different positions. A leader who makes his/her team members feel that their interests and positions are heard and respected can go a long way toward achieving constructive outcomes and building trust despite conflicting interests (Saltman et al. Citation2006). Continuing professional development in team management, negotiation and conflict resolution can be especially helpful to leaders who struggle with handling disagreements among team members, along with mentoring and coaching. Concluding meetings by validating points of agreement and acknowledging unresolved disagreements will also build trust among team members. Consensus building through asking team members if they “can live with” even if they “don’t totally agree” with the plan going forward (similar to what was noted with stakeholders in Tip 2) is another way to make compromise more explicit and support productive team efforts.

Monitoring

Tip 11

Check-in with stakeholders, manage their expectations and anticipate changing interests

The appropriate timing and nature of stakeholder interactions can be challenging. For some stakeholders, periodic informal updates are sufficient to assure them that all is on track or to warn them that task completion is at risk. Other stakeholders may require less frequent but more formal updates and it is important for leaders to plan for both types of interactions (Shi and Johnson Citation2014). Setting calendar reminders can help if providing a variety of updates is not a natural way for the leader to function. Making it clear when it is “For Your Information (FYI) – no action needed” and when specific advice or assistance is needed will help the stakeholder respond appropriately as well. Inviting stakeholders to specific team interactions that are relevant for them can also build their commitment to the effort because they can engage selectively and effectively.

Tip 12

Review progress on tasks, revise plans as needed, and garner team support

Implementing the first eleven tips will establish a strong foundation for efficient accomplishment of this final tip. As program leaders work with their team to develop drafts of the final results, a road map can be created to show how and when various goals were achieved. This is a useful mechanism to gain team members’ buy-in before sharing more broadly with other stakeholders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2017). The process also provides an opportunity to celebrate accomplishments and identify items that can be the focus for improvement in subsequent efforts. Sometimes the descriptions of the results will need to be revised based on other stakeholder input; that task becomes much easier if the entire team feels ownership of the program design and implementation.

The tips described above can be applied by HPEd Program Leaders with varying levels of experience, skills, resources and adapted to multiple contexts. shows examples of challenges related to needs assessment during the design of a program and how the tips can guide leaders in managing the complexities of relationship challenges with multiple stakeholders.

Table 1. Examples of considerations that can arise when launching an interprofessional education program.

Discussion/conclusions

Health professions educational leaders work directly with and within two complex systems (that of education and healthcare), each of which are made up of many interconnecting as well as seemingly disconnected elements. They face many challenges as they engage various stakeholders with competing interests and demands (Shi and Johnson Citation2014). The evolution of leadership theories during the past 100 years from the “great person” theory to the more recent relationship/transformational and principled leader theories (Shi and Johnson Citation2014; Amanchukwu et al. Citation2015) reflects the importance of leadership in the context of inherently complex systems. Additionally, addressing underlying organizational culture is necessary to understand key factors that influence program outcomes, a CQI mind-set can help leaders to work systematically and incrementally in program design.

The tips described are based on an extensive review of literature on program implementation and evaluation, as well as authors’ practical experiences in addressing complex dynamics associated with common and competing interests during the design and implementation of a HPEd program (Fallon and Zgodzinski Citation2012; Shi and Johnson Citation2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2017; Institute for Healthcare Improvement Citation2017). They provide a systematic structure for gaining buy-in and determining what is feasible given time and other resource constraints and emphasize the importance of up-front efforts that enable more efficient and productive implementation. Finally, these tips offer a robust framework for designing and evaluating educational programs that require grappling with rapidly evolving circumstances filled with ambiguity and uncertainty – including the challenges associated with conducting educational research: lack of funding, time constraints due to competing responsibilities, finding collaborators/mentors, maintaining methodological rigor/lack of methods training, and lack of perceived value of educational research/departmental support (Smesny et al. Citation2007; LaMantia et al. Citation2012; Jordan et al. Citation2016).

Notes on contributors

Roger A. Edwards, ScD, is an Associate Professor at the MGH Institute of Health Professions and Associate Director of the Health Professions Education Program (Center for Interprofessional Studies and Innovation) in Boston, MA. His main interests include diffusion of innovations, public health, program evaluation, and research methods in HPEd.

Sandhya Venugopal, MD, MS-HPEd, is an Associate Professor of Medicine at University of California (Davis) School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA and an Adjunct Associate Professor at the MGH Institute of Health Professions. She is a noninvasive cardiologist and Associate Director for the cardiovascular training program. Her interests include scholarship of teaching and learning, program evaluation and clinical reasoning.

Deborah Navedo, PhD, is an Associate Professor and the founding director of the MGH Institute’s HPEd Program’s masters degree. She is a Paediatric Nurse Practitioner by background with PhD in Higher Education Administration focusing on reflective learning. She has focused her career on curriculum and program development and implementation. Her interests include reflective learning and debriefing in simulation, instructor training, and interprofessional education related faculty development.

Subha Ramani, MBBS, MMEd, is the Director of Evaluation and Scholars in Medical Education Pathway for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Adjunct Associate Professor at the MGH Institute of Health Professions and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a general internist and educationalist with particular interest in workplace assessment, feedback, bedside teaching, qualitative methodology and staff development. She is currently a PhD candidate at the School of Health Professions Education, University of Maastricht, Netherlands.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2017. Milestones. [online]; [accessed 2017 May 27]. http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Overview.

- Amanchukwu RN, Stanley GJ, Ololube NP. 2015. A review of leadership theories, principles and styles and their relevance to educational management. Management. 5:6–14.

- Barzansky B, Hunt D, Moineau G, Ahn D, Lai CW, Humphrey H, Peterson L. 2015. Continuous quality improvement in an accreditation system for undergraduate medical education: benefits and challenges. Med Teach. 37:1032–1038.

- Beaudry M. 2013. QI tools to support measurement activities [online]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [accessed 2017 May 27]. https://www.cdc.gov/stltpublichealth/pimnetwork/eventdocs/2013/may/05232013slides.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. [online]; [accessed 2017 May 27]. https://www.cdc.gov/eval/.

- Chambers D, Simpson L, Neta G, von Thiele Schwarz U, Percy-Laurry A, Aarons GA, Neta G, Brownson R, Vogel A, Wiltsey Stirman S, et al. 2017. Proceedings from the 9th annual conference on the science of dissemination and implementation. Implement Sci. 12(Suppl 1):48.

- Clegg D, Barker R. 1994. CASE method fast-track. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Cohen R, Murnaghan L, Collins J, Pratt D. 2005. An update on master's degrees in medical education. Med Teach. 27:686–692.

- Creswell JW. 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications, Inc.

- Fallon LF, Zgodzinski EJ. 2012. Essentials of public health management. 3rd ed. Sudbury (MA): Jones & Barlett Learning.

- Frenk J, Lincoln C, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, et al. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 376:1923–1958.

- Frye AW, Hemmer PA. 2012. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide No. 67. Med Teach. 34:e288–e299.

- Haji F, Morin MP, Parker K. 2013. Rethinking programme evaluation in health professions education: beyond ‘did it work?’ Med Educ. 47:342–351.

- Ham C, Berwick D, Dixon J. 2016. Improving quality in the English NHS: a strategy for action [online]. The King’s Fund; [accessed 2017 Oct 10]. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/quality-improvement.

- Hogg RV, Hogg MC. 1995. Continuous quality improvement in higher education. Int Stat Rev. 63:35–48.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2017. Resources for public health quality improvement. [online]; [accessed 2017 May 27]. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/ResourcesforPublicHealth.aspx.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2017. Cause and effect diagram [online]; [accessed 2017 May 27]. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/CauseandEffectDiagram.aspx.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2017. Science of improvement: testing changes [online]; [accessed 2017 May 27]. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementTestingChanges.aspx.

- Jordan J, Coates WC, Clarke S, Runde D, Fowlkes E, Kurth J, Yarris L. 2016. The uphill battle of performing educational scholarship: barriers education researchers face. Ann Emerg Med. 68:S30.

- LaMantia J, Hamstra SJ, Martin DR, Searle N, Love J, Castaneda J, Aziz-Bose R, Smith M, Griswold-Therodorson S, Leuck J. 2012. Faculty development in medical education research. Acad Emerg Med. 19:1462–1467.

- Mennin S. 2013. Health professions education: complexity, teaching and learning. In: Sturmberg JP, Martin CM, editors. Handbook of systems and complexity in health. New York (NY): Springer; p. 755–766.

- Mennin S. 2010. Complexity and health professions education: a basic glossary. J Eval Clin Pract. 16:838–840.

- Nakanjako D, Namagala E, Semeere A, Kigozi J, Sempa J, Ddamulira JB, Katamba A, Biraro S, Naikoba S, Mashalla Y, et al. 2015. Global health leadership training in resource-limited settings: a collaborative approach by academic institutions and local health care programs in Uganda. Hum Resour Health. 13:87.

- Rath T. 2007. Strengthsfinder 2.0. New York (NY): Gallup Press.

- Rea P, Kerzner H. 1997. Strategic planning: a practical guide. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Rossi PH, Freeman HE, Lipsey MW. 1999. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications.

- Saltman DC, O’Dea NA, Kidd MR. 2006. Conflict management: a primer for doctors in training. Postgrad Med J. 82:9–12.

- Schein EH. 2017. Organizational culture and leadership. 5th ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Shi L, Johnson JA. 2014. Novick & morrow’s public health administration. 3rd ed. Burlington (MA): Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Smesny AL, Williams JS, Brazeau GA, Weber RJ, Matthews HW, Das SK. 2007. Barriers to scholarship in dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 71:91.

- Tekian A, Artino A. 2013. AM last page: master's degree in health professions education programs. Acad Med. 88:1399.

- Tekian A, Taylor D. 2017. Master’s degrees: meeting the standards for medical and health professions education – AMEE Guide. Med Teach. 39:906–913.

- The Health Foundation. 2012. Quality improvement training for healthcare professionals [online]; [accessed 2017 Oct 10]. http://www.health.org.uk/publication/quality-improvement-training-healthcare-professionals.

- World Federation of Medical Education. 2017. Master’s [online]; [accessed 2017 Jun 9]. http://wfme.org/standards/standards-for-master-s-degrees-in-medical-and-health-professions-education.