Abstract

Introduction: The hidden curriculum, commonly described in negative terms, is considered highly influential in medical education, especially in the clinical workplace. Structured approaches to address it are limited in number and scope.

Methods and results: This paper presents a practical, value-neutral method called REVIEW (Reflecting & Evaluating Values Implicit in Education in the Workplace), to facilitate reflection and discussion on the hidden curriculum by faculty members and trainees. REVIEW approaches the hidden curriculum as a reflection of the professional microculture of a clinical team. This microculture results from collective problem solving and mutual negotiation when facing different, often conflicting, demands and interests, and their underlying values in daily clinical practice. Using this nonjudgmental conceptual framework, REVIEW employs a series of 50 culture statements that must be prioritized using Q-sort methodology, reflecting how the culture in a particular clinical context (e.g. ward or department) is perceived by faculty members and trainees. This procedure can be done individually or in groups. Most important is the resulting team discussion after the exercise – a discussion about perceptions of actual team culture and the culture desired by the team.

Discussion and conclusions: Our early experiences suggest that REVIEW can be a useful tool for addressing the hidden curriculum.

Introduction

Learning in medical education takes place, to a large extent, outside a formal curriculum (O’Donnell Citation2014). Clinical workplaces are essential for the curriculum, but much of what happens in these contexts is not prescribed nor foreseen in curriculum documents. Medical education literature uses the term “hidden curriculum” to refer to the set of implicit messages about values, norms, and attitudes that learners infer from the behavior of individual role models as well as from group dynamics, processes, rituals, and structures (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Hafferty Citation1998; Wear Citation1998; Haidet and Stein Citation2006; Haidet et al. Citation2006; Gaufberg et al. Citation2010; Karnieli-Miller et al. Citation2010; Ewen et al. Citation2012; Higashi et al. Citation2013; O’Donnell Citation2014; Lawrence et al. Citation2017; Hafferty and Martimianakis Citation2017). These values, norms, attitudes, and related behaviors can be summarized as “culture” (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Haidet and Stein Citation2006). The hidden curriculum in a specific clinical workplace thus refers to the transfer of the culture of that workplace. In contrast to the formal curriculum, the hidden curriculum is not documented and it is inferred by learners rather than delivered intentionally by faculty (O’Donnell Citation2014).

Many authors have emphasized the importance of the hidden curriculum and some even consider it more powerful than the formal curriculum (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Hafferty Citation1998; Karnieli-Miller et al. Citation2010; Gaufberg et al. Citation2010; Hafler et al. Citation2011; Wilson et al. Citation2013; Stern Citation2014). In particular, it strongly influences professional identity development of trainees (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Burford Citation2012; Goldie Citation2012; Jarvis-Selinger et al. Citation2012; Cruess et al. Citation2014; Lawrence et al. Citation2017). The hidden curriculum may align with or operate contrary to the formal curriculum (Stern Citation1998a, Citation1998b; Hafferty and Hafler Citation2011; Lawrence et al. Citation2017). Webster and colleagues describe an instructive example of incongruence between the hidden and formal curriculum. A policy to reduce waiting times in an emergency department led to a “hidden curriculum of efficiency”: trainees “were learning that knowing how to deflect patients elsewhere is an important component of good medical practice” (Webster et al. Citation2015, p. 61). Other examples of hidden curriculum messages are “Doctors never admit to not knowing something” and “Leaving the hospital (to eat, sleep, etc.) is a sign of weakness” (Haidet and Stein Citation2006, p. 17). Such divergences between the formal and the hidden curriculum may put quality of care and patient safety at risk and countervailing messages may cause dissatisfaction, cynicism, moral distress, and burnout in trainees (Hafferty and Franks Citation1994; Haidet et al. Citation2006, Hafler et al. Citation2011; Berger Citation2014; Haidet and Teal Citation2014; O’Donnell Citation2014; Webster et al. Citation2015).

Many publications have drawn attention to the hidden curriculum, some of which offer instruments to assess or measure the hidden curriculum. For example, Haidet and colleagues developed an instrument, C3, to examine patient centeredness (Haidet et al. Citation2005; Haidet et al. Citation2006; Haidet and Teal Citation2014). Tools like the C3 instrument rely on learner responses to measure the hidden curriculum. Our approach differs in that we (1) invite faculty members as well as learners to explicate the hidden curriculum and (2) use the tool to help groups not just assess, but explore and potentially address it. From an educational perspective, the challenge is in how to make dilemmas explicit (Stern and Papadakis Citation2006) and to neutrally question choices and priorities, rather than condemning the hidden curriculum or its “purveyors”. Our goal was to take a positive, non-threatening approach to facilitating reflection and discussion on clinical workplace cultures. To do so, we employed two concepts from the literature on professions and professionals, “coping” and “culture”, to reconceptualize the hidden curriculum.

Coping and culture – a conceptual framework

Public administration literature introduced the concept of “coping” to explain how public service professionals, such as health professionals and educators, deal with work pressures resulting from – increasing – demands and expectations (Hupe and Van der Krogt Citation2013). Adapting a definition by Tummers et al (Citation2015, p. 3–4), we define “coping” as: behavioral efforts clinicians and trainees employ during their work, in order to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts they face on an everyday basis. We consider the culture of a clinical team – a ward or a department – as the result of coping on a group level. This view aligns with Champy’s work on the sociology of professions (Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2011). Champy advocates an understanding of “culture” that acknowledges both the homogeneity of a set of basic values of a profession – e.g. physicians – and the diversity with which these values appear in different segments of the profession and over the course of time. This diversity pertains to the hierarchy among different values as well as their interpretation and their translation into behavior. According to Champy, specific versions of a professional culture result from collective problem solving when groups face contradictions and tensions between underlying professional values. We use the term “professional microculture” to refer to such specific versions of a professional culture. For instance, Haidet and colleagues identified different “professional microcultures” in the clinical learning environment among nine medical schools (Haidet et al. Citation2006).

Within our conceptual framework, the hidden curriculum is generated by a professional microculture resulting from a process of group coping in which professional values are prioritized and interpreted in a specific way. This framework allows a value-neutral understanding of the hidden curriculum, where values are usually not dichotomous (e.g. “honest” versus “dishonest”) and equally meritorious values, such as “integrity” and “efficiency”, can be in conflict (O’Donnell Citation2014, p. 13). Within this framework, discrepancies between the formal and hidden curriculum are not attributed to (individual, group, or organizational) shortcomings, but viewed in the light of a complex clinical practice that forces individuals and groups to make, often tacitly and unconsciously, choices, prioritizations, and compromises.

Using this conceptualization of the hidden curriculum, we developed a practical tool and associated procedures to address the hidden curriculum in clinical workplaces: REVIEW (Reflecting & Evaluating Values Implicit in Education in the Workplace). In this article, we describe the development of the REVIEW tool and provide preliminary validity evidence to support its use. We piloted two different procedures and present the results of these pilots.

Methods and results

Setting and participants

We developed REVIEW at University Medical Center (UMC) Utrecht in the Netherlands. Residents and faculty members from four UMC Utrecht and two other Dutch postgraduate programs participated in pilots with REVIEW.

Structure of REVIEW tool

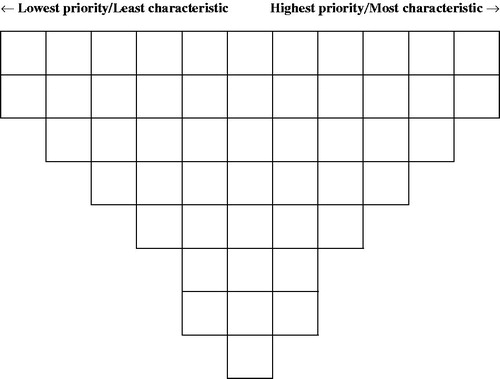

To best reflect our conceptual framework, we chose Q-methodology as the information-gathering strategy for our tool. Q-methodology has been used to collect and explore a variety of subjective opinions (Cross Citation2005; Watts and Stenner Citation2012). It asks respondents to rank order items – the Q-set – in a forced normal distribution. The lowest priority items are placed in the extreme left position on a grid, and the highest priority items on the far right. Most items must be placed around the center of the grid, which has the most space (). Each item is then scored based on its position on the grid. The lowest priority items – those occupying the left-most position on the grid – receive 1 point. Positions to the right gain additional points up to 11 points for the items occupying the right-most position.

Item development for REVIEW tool

Items for a Q-set – the statements that must be prioritized, usually 40–80 – are typically derived from a variety of sources such as professional and popular literature, interviews, and the media (Cross Citation2005; Watts and Stenner Citation2012). We similarly used multiple sources to ensure that statements for our Q-set encompassed behaviors reflecting professional values demanded from clinicians by various stakeholders and from different perspectives. We searched the medical education literature on hidden curriculum and (un)professional behavior, formal documents such as mission statements of health care organizations, as well as professional literature, blogs, and interviews. We included these latter sources as they provide information generally not found in the more formal literature. They often articulate values and demands – as well as resulting conflicts and dilemmas – as experienced by professionals themselves. Of note, in Q-methodology, sources are searched to develop items sets that are broadly representative of a theme, yet manageable (i.e. not too large) for respondents (Watts and Stenner Citation2012). Our search therefore focused on saturation and does not represent a systematic review of potential sources.

We formulated an initial set of 51 statements based on the search results. Each opens with “In our team [unit/department] we…” followed by a short description of behavior. As recommended for Q-sets (Watts and Stenner Citation2012), we avoided negative statements expressed as “we don’t…” and statements with more than one proposition. We aimed at clarity of formulation without being too specific, to capture general values and demands. For instance, the statement “we always treat each patient respectfully under all circumstances” leaves room for reflection and discussion about the interpretation of the concept “respect” and the kinds of behavior that demonstrate it. We avoided qualifications such as “mostly”, “if necessary”, or “if possible” because respondents modify statement values by placing them more on the left or right side of the grid. The 51 statements can be roughly grouped into seven categories centered around the interests of (1) individual patients, (2) the professional him/herself, (3) colleagues, (4) education and professional development, (5) compliance with rules and regulations, (6) cost consciousness, and (7) quality of care. These partly overlapping categories served as a structural guide during item generation to ensure inclusion of a breadth of important concepts.

Tool content and response process validation

While REVIEW is not intended for use as an assessment tool or procedure, the results of the Q-sorting exercise should nevertheless provide a valid reflection of a group’s microculture to promote valuable discussion among the participants. Following the validity framework proposed by The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA/APA/NCME Citation2014), we gathered additional evidence on the content validity of our Q-set statements and evidence on the response process, that is, how respondents understand the statements and Q-sorting procedure.

First, we asked six clinicians to review the initial statements for topic relevance (i.e. culture of clinical groups), completeness and clarity. Based on their feedback, we eliminated four statements because of overlap and added two new statements. We revised 39 statements, one of which was split into two. Revisions included increasing accuracy and consistency in wording, adding relevant contextual information, using more generic terminology, and shortening statements. Eleven statements remained unchanged. The revised set contained 50 statements.

To assess the response process, we asked nine other faculty members and residents to Q-sort the statements, according to how well they felt each one reflected their own group culture. All nine participants carried out the Q-sorting procedure in 20–30 min. Some of them provided suggestions for adjusting instructions for the exercise, which we incorporated. Although most participants considered the Q-set of 50 statements to be quite large, the majority advised against reducing it because they found it rich and adequate. We therefore maintained all 50 statements in the final REVIEW Q-set (see ).

Table 1. The Q-set: themes and statements.

Pilot implementation: feasibility and additional validity evidence

We developed and pilot tested two different implementation procedures. One procedure utilizes an online version of the tool for asynchronous individual completion of the Q-sorting task, and facilitates the production of result reports. The second procedure uses a card game version for synchronous group Q-sorting and is appropriate for workshop settings (see ).

Table 2. Recommended procedure.

Online version

We pilot tested the online version of REVIEW in 2015–2016 with faculty members and residents in four UMCU Utrecht postgraduate programs. We initially invited three postgraduate programs of moderate size (15–20 residents each) to participate. A fourth postgraduate program (55 residents), spontaneously asked to be included. The programs represented surgical and non-surgical specialties. The program directors emailed invitations to all of their faculty members and residents, to anonymously complete the REVIEW Q-sorting exercise online, based on how they perceived the professional microculture in the department. Participation was voluntary; reminders were sent after 1–2 weeks. A total of 139 responses were submitted which we estimated to be somewhat more than 50%. The inconsistent inclusion of residents just leaving a rotation precluded calculation of a more precise response rate.

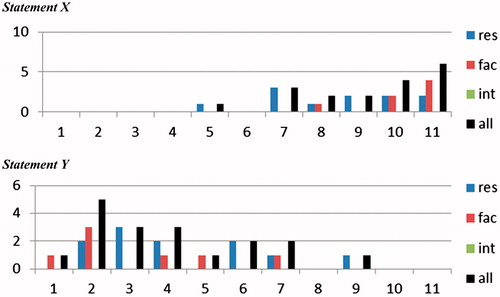

We aggregated the individual results into reports for each group using histograms to show frequency distribution of scores across statements, and among different subgroups of respondents, for example, faculty members and residents (see ). For the sake of anonymity, results of subgroups were only provided if they contained at least four respondents. Group reports were sent to the relevant program directors for analysis, interpretation, and action.

Figure 2. Group report (sample of two statements). res = residents (N = 11); fac = faculty (N = 7); int = medical students (in this example N = 0). Number of respondents placing the statement in positions 1 (most left: least characteristic) to 11 (most right: most characteristic). Black bars represent all respondents (N = 18). A complete group report contains histograms for each of the 50 statements, offering an overview of the perception of statements as relatively more (e.g. X) or less (e.g. Y) characteristic for a specific culture, and of divergence of perceptions between respondents.

As the REVIEW data are collected exclusively to facilitate reflection and discussion, the first author (HM) met with each program director and a resident and/or another faculty member to discuss and analyze the reports and to select key topics for group discussion. Program directors generally focused on statements frequently ranked as very characteristic or very uncharacteristic for the group’s culture. Group discussions on the scoring results took place during regular plenary meetings led by the program director or department chair. These 30–60 min meetings were attended by 10–30 faculty members and residents and focused on recognizability of the REVIEW results, differences in perceptions of the culture, satisfaction with specific aspects of the culture and aspects of the culture that group members desired to change. HM attended all sessions and took written notes of the discussions. To protect the privacy of meeting attendants, we decided against audio recordings. To ensure accuracy, a sample (one session) was sent to a subset of discussion participants for member verification. We analyzed group discussion notes as well as individual feedback comments.

Card game version

In 2017, two residency programs in another Dutch University Medical Center asked to use REVIEW, providing the opportunity to test REVIEW in a 2-part workshop format. One program received Parts 1 and 2 as two 2-h workshops separated by 2 weeks. The other received both parts in one 3.5-h workshop.

In Part 1 of the workshops, subgroups of 5–7 faculty members or residents rank ordered the statements in a card game version of the tool, and answered questions 2a and b of the recommended procedure (see ). Summaries of all subgroup results were discussed by the whole group. Based on this discussion, in the two workshops 11 and 4 statements, respectively, were selected for improvement (e.g. “systematically take time for our own professional development”). In Part 2, we posted the selected statements and invited participants to gather by the one on which they preferred to work. The participants were then divided into five subgroups by statement or combination of statements, to develop plans for improvement. At the end of the workshops, the subgroups presented their plans and practical strategies, and individuals were appointed to implement these.

Feasibility

Program directors as well as many faculty and residents appeared interested and engaged with REVIEW. The online ranking of statements took approximately 20 min. In the workshops, ranking of statements and answering questions 2a and b of the recommended procedure (see ) took about 45 min. As anticipated, opinions about ease of tool use varied. Respondents generally experienced the Q-sorting process as more challenging than scoring statements on a Likert-type scale. Some appreciated this aspect while others found it frustrating. While some respondents in the online pilots found the number of statements too high and the exercise too time consuming, others appreciated the richness and relevance of the 50 statements and advised against reducing the set. Lastly, the aggregated group reports, resulting from the online version, were appreciated as an accessible overview.

Validity evidence

Ranking results were generally recognized as reflecting the group culture. Because REVIEW is intended to capture potentially varying yet still valid perceptions of the department’s professional microculture by individuals and subgroups, we did not perform the typical analyzes for validity evidence of internal structure (e.g. item factor analysis, inter-item correlations, inter-rater reliabilities). Similarly, because we know of no other tools to measure professional microcultures from the perspective of those contributing to the culture, we did not examine the relationship of our results to other variables.

Feedback from pilot participants suggest evidence for consequential validity. Participants of both the online and card game versions of the pilot reported REVIEW raised individual and group awareness, and stimulated reflection and discussion of the perceived culture which had previously been hidden or gone unnoticed. One participant commented that “REVIEW functioned as an eye opener”. Participants noted that REVIEW focused on topics that are usually not openly addressed but deserve attention. They stated that REVIEW pays attention to aspects of clinical work that are difficult to quantify, but are crucial for quality of care and patient safety. For instance, one resident commented that “we apparently communicate well with our patients but less with each other”.

Several program directors noted that REVIEW facilitated the discussion of these topics in a non-threatening, constructive, and coherent way. The generic wording of the statements was appreciated for its ability to stimulate discussion and awareness of different perceptions within a group. This was further facilitated by group reports highlighting differences in perceptions. Another valued aspect of REVIEW was that it allowed discussion of delicate and controversial issues in a setting that was removed from the urgency and pressure of acute clinical problems.

REVIEW also aims to facilitate the formulation of concrete action plans to change aspects of the hidden curriculum and culture. The pilots using the online version generated less action plans than the card game version, as discussions about ranking results took place exclusively in large groups and within tight time schedules. Program directors and others suggested that plenary group discussions should be followed by more in-depth smaller group discussions of selected REVIEW statements, to develop concrete goals and specific action plans to realize the desired group culture. To fully exploit the capability of REVIEW, sufficient time needs to be set aside for guided and small group discussion in Step 4 of the recommended procedure (see ). The pilots involving workshops (card game version) resulted in several action plans, and participants found the experience appealing, useful, and inspiring. Here, rank ordering of the statements was a collaborative activity among subgroups with time earmarked for exchanging perceptions of the culture. Moreover, there was sufficient time for plenary discussion about subgroup presentations, desire to change aspects of the culture, and how change could be possible.

Two additional observations and consequences from the pilot workshops deserve to be mentioned here. In the first workshop, participants themselves related their professional culture to the hidden curriculum. They perceived “asking questions when there is something we don’t know” as not very characteristic for their culture and decided that this could “send” the objectionable “message” (in terms of the hidden curriculum) that asking questions, for example, during patient handovers, is “not done”. They decided to work on this aspect of their culture to better align it with the formal curriculum that encourages active learning. In the second workshop, a chief resident commented that REVIEW helped residents to realize that, rather than being merely a victim of the existing culture, they can influence this culture.

Discussion and conclusions

We have developed and tested REVIEW, a method to systematically explore and facilitate reflection and discussion on the hidden curriculum in the clinical workplace. The “hidden”, as opposed to the “formal”, curriculum refers to a phenomenon that has been described in widely varying ways (Hafferty and Martimianakis Citation2017; Lawrence et al. Citation2017). We approached the hidden curriculum as a reflection of the professional microculture of a specific workplace, and we operationalized professional microculture as the result of a process of group coping with different demands and their underlying values. REVIEW aims at making professional microcultures visible.

REVIEW consists of two components forming an integrated whole: an information-gathering tool and the procedures using it. The information-gathering tool includes 50 statements that describe behaviors. Faculty members and trainees must Q-sort these statements to reflect their perceptions of the local culture. The tool may be applied using two strategies, each including procedures for analysis, discussion, and evaluation of the ranking results as well as for planning next steps in addressing the culture. We found that, with the differing impacts of our two pilot approaches, the procedures are a key component of REVIEW and time must be set aside for group discussion of results and action planning. When using the online version, the recommended procedures should be elaborated further, to ensure in-depth discussion.

Based on our pilot studies, we believe there is satisfactory evidence (including feasibility and content, response process, and consequential validity evidence) to support the use of REVIEW in helping individuals and groups – including learners – gain insights into their professional microculture and into the hidden curriculum created by this microculture. With REVIEW, hidden curricula may be addressed and affected in two ways. (1) By exposing dilemmas and explaining choices and compromises underlying the professional microculture, REVIEW may foster more explicit education, that is, strengthen the positive and reducing the negative impact of the hidden curriculum. (2) By facilitating groups (e.g. clinical teams, units, departments) to change aspects of their professional microculture, it may help to align the content of the hidden curriculum in their workplaces with the formal curriculum.

We think that REVIEW’s effectiveness relates to its non-judgmental approach. As all REVIEW statements describe defensible behaviors – mirroring the necessity of prioritization and compromise with regard to values and demands in the clinical workplace – no ranking is a priori “right” or “wrong”. REVIEW therefore supports insight but leaves it to respondents – groups or individuals – to evaluate their culture and to decide whether to change or not.

We believe our REVIEW method expands upon prior approaches to the hidden curriculum in four respects. Firstly, our perspective on the hidden curriculum, as a reflection of a professional microculture, blurs the common distinction between propagators and receivers of the hidden curriculum, as all members of a group are influenced by and sustain, influence, and transfer the microculture. REVIEW therefore engages both learners and teachers, instead of learners alone (Hafler et al. Citation2011), in identifying and acknowledging the hidden curriculum, as was recommended by Hodges and Kuper (Citation2014).

Secondly, there is a “tendency among medical education reformers […] to seek solutions [regarding hidden curriculum features] at the level of individuals (for example students and faculty) […]” (Hafferty and O’Donnell Citation2014, p. 22). However, social interactions within teams contribute strongly to creating and sustaining the microculture transferred in the hidden curriculum. REVIEW addresses individuals as well as teams.

Thirdly, current descriptions of the hidden curriculum as a set of “messages” – about values, beliefs, and attitudes – correctly frame it as a communication phenomenon, implying the possibility of mis- or over-interpretation. This implication, however, has not yet been systematically exploited as a lens to analyze the hidden curriculum. With REVIEW, we explicitly acknowledge that the hidden curriculum is ultimately the result of perceptions and interpretations.

Finally, the hidden curriculum is often approached negatively: it is the “scapegoat” and “usual suspect” (O’Donnell Citation2014, p. 2). In REVIEW, we approach the hidden curriculum as it relates to the highly complex nature of the clinical environment forcing clinical professionals and trainees to deal with different and sometimes conflicting demands and interests and their underlying values.

REVIEW is a promising method but there are some directions for its use that others considering implementation need to be aware of. (1) REVIEW is meant to be applied for units – teams, departments, organizations – that share, to some extent, a group culture. (2) Vital for participation of respondents and a meaningful discussion is the commitment of educational and departmental leaders and resident representatives to exploring the issue of “culture” and its transfer. (3) As REVIEW requires a working and learning climate that is open to reflection and dialog, we would not anticipate that it will work in seriously problematic situations. (4) As REVIEW was designed as a catalyst for reflection and discussion and uses forced-choice rank ordering of statements, ranking results have no value per se. They should not be mistaken for or shared with higher management as quality indicators, or used for benchmarking. REVIEW was not created as a tool to assess the culture or the hidden curriculum to enable comparisons of departments and cannot serve that purpose.

REVIEW may have limitations for transferability across contexts. It was developed to address the hidden curriculum and professional microcultures in Dutch clinical settings. The statements in our Q-set were partly inspired by sources from the Dutch context and may be less applicable to other clinical education contexts. However, with an adapted item set, the method can be applied in clinical contexts in other countries and in other professions or occupational groups dealing with competing demands and values.

In conclusion, REVIEW is a promising new approach for addressing hidden curricula by reviewing professional microcultures. It is a nonjudgmental tool that can be used with teams including faculty members and trainees. We have provided initial validity evidence and shown that REVIEW can result in willingness to talk about aspects of culture and plan for change. An area for future study is whether groups are able to implement their plans for change and result in a shift in their microculture. We encourage others to apply it and provide additional validity studies as well as longitudinal outcome studies to demonstrate culture change within teams as a result of using REVIEW.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from The Netherlands Association for Medical Education Ethical Review Board.

Glossary

Hidden curriculum: The hidden curriculum is generated by a professional microculture resulting from a process of group coping in which professional values are prioritized and interpreted in a specific way.

Professional microculture: A specific version of a professional culture in which professional values are prioritized and interpreted in a specific way.

Notes on contributors

Hanneke Mulder, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Innovation of Medical Education at the Center for Research and Development of Education at University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Edith ter Braak, MD PhD, is internist and Professor of Medical Education at the Education Center of University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

H. Carrie Chen, MD PhD, began this work while a visiting professor at the Center for Research and Development of Education at University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands. She is currently professor of pediatrics and Associate Dean for Assessment and Educational Scholarship at Georgetown University School of Medicine, USA.

Olle ten Cate, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education and Director at the Center for Research and Development of Education at University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Thijs Jansen, Inge Pool, Sjoukje van den Broek, and Manon Kluijtmans for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- [AERA] American Educational Research Association; [APA] American Psychological Association; [NCME] National Council on Measurement in Education. 2014. Validity. In: The standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington (DC): American Educational Research Association; p. 11–31.

- Berger JT. 2014. Moral distress in medical education and training. J Gen Intern Med. 29:395–398.

- Burford B. 2012. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 46:143–152.

- Champy F. 2009a. La culture professionnelle des architectes. In: Demazière D, Gadéa C, editors. Sociologie des groupes professionnels: acquis récents et nouveaux défis. Paris: Éditions La Découverte; p. 152–162.

- Champy F. 2009b. La sociologie des professions. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Champy F. 2011. Nouvelle théorie sociologique des professions. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Cross RM. 2005. Exploring attitudes: the case for Q methodology. Health Educ Res. 20:206–213.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. 2014. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 89:1446–1451.

- Ewen S, Mazel O, Knoche D. 2012. Exposing the hidden curriculum influencing medical education on the health of Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand: the role of the Critical Reflection Tool. Acad Med. 87:200–205.

- Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. 2010. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 85:1709–1716.

- Goldie J. 2012. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 34:e641–e648.

- Hafferty FW. 1998. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 73:403–407.

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. 1994. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 69:861–871.

- Hafferty FW, Hafler JP. 2011. The hidden curriculum, structural disconnects, and the socialization of new professionals. In: Hafler JP, editor. Extraordinary learning in the workplace. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 17–35.

- Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF. 2014. Working within the framework: some personal and system-level journeys into the field. In: Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; p. 21–22.

- Hafferty FW, Martimianakis MA. 2017. A rose by other names: some general musings on Lawrence and colleagues’ hidden curriculum scoping review. Acad Med. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002025.

- Hafler JP, Ownby AR, Thompson BM, Fasser CE, Grigsby K, Haidet P, Kahn MJ, Hafferty FW. 2011. Decoding the learning environment of medical education: a hidden curriculum perspective for faculty development. Acad Med. 86:440–444.

- Haidet P, Kelly PA, Bentley S, Blatt B, Chou CL, Fortin AH, Gordon G, Gracey C, Harrell H, Hatem DS, et al. 2006. Not the same everywhere: patient-centered learning environments at nine medical schools. J Gen Intern Med. 21:405–409.

- Haidet P, Kelly PA, Chou C. 2005. Characterizing the patient-centeredness of hidden curricula in medical schools: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 80:44–50.

- Haidet P, Stein HF. 2006. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 21:S16–S20.

- Haidet P, Teal CR. 2014. Organizing chaos: a conceptual framework for assessing hidden curricula in medical education. In: Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; p. 84–95.

- Higashi RT, Tillack A, Steinman MA, Johnston CB, Harper GM. 2013. The ‘worthy’ patient: rethinking the ‘hidden curriculum’ in medical education. Anthropol Med. 20:13–23.

- Hodges BD, Kuper A. 2014. Education reform and the hidden curriculum: the Canadian journey. In: Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; p. 41–50.

- Hupe P, van der Krogt T. 2013. Professionals dealing with pressures. In: Noordegraaf M, Steijn B, editors. Professionals under pressure: the reconfiguration of professional work in changing public services. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; p. 55–72.

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. 2012. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 87:1185–1190.

- Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Holtman MC, Clyman SG, Inui TS. 2010. Medical students' professionalism narratives: a window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 85:124–133.

- Lawrence C, Mhlaba T, Stewart KA, Moletsane R, Gaede B, Moshabela M. 2017. The hidden curricula of medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002004.

- O’Donnell JF. 2014. Introduction: The hidden curriculum – a focus on learning and closing the gap. In: Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; p. 1–20.

- Stern DT. 1998a. Practicing what we preach? An analysis of the curriculum of values in medical education. Am J Med. 104:569–575.

- Stern DT. 1998b. Culture, communication, and the informal curriculum: in search of the informal curriculum: when and where professional values are taught. Acad Med. 73:S28–S30.

- Stern DT. 2014. A hidden narrative. In: Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF, editors. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; p. 23–31.

- Stern DT, Papadakis M. 2006. The developing physician – becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 355:1794–1799.

- Tummers LLG, Bekkers V, Vink E, Musheno M. 2015. Coping during public service delivery: a conceptualization and systematic review of the literature. J Public Adm Res Theory. 25:1099–1126.

- Watts S, Stenner P. 2012. Doing Q methodological research: theory, method and interpretation. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications.

- Wear D. 1998. On white coats and professional development: the formal and the hidden curricula. Ann Intern Med. 129:734–737.

- Webster F, Rice K, Dainty KN, Zwarenstein M, Durant S, Kuper A. 2015. Failure to cope: the hidden curriculum of emergency department wait times and the implications for clinical training. Acad Med. 90:56–62.

- Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. 2013. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 25:369–373.