Abstract

The problem: Clinical practice commonly presents new doctors with situations that they are incapable of managing safely. This harms patients and stresses the new doctors and other clinicians. Unpreparedness for practice remains a problem despite changes in curricula from apprenticeship to outcome-based designs. This is unsurprising because capability depends on learning from practical experience in supportive learning environments. To assure the care of patients and well-being of residents, the pedagogy of medical students’ practice-based education is in urgent need of an overhaul.

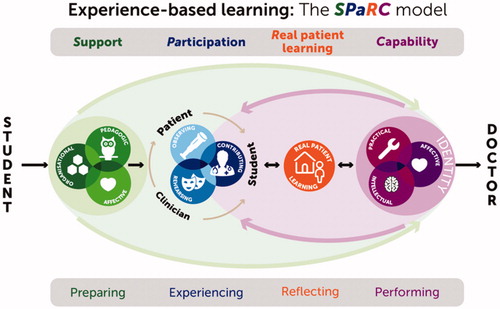

This Guide: Experience based learning (ExBL) is a 21st century pedagogy of practice-based learning, derived from best current theory and evidence. ExBL specifies capabilities that medical students need to acquire from practical experience. It exemplifies how clinicians’ behavior can help students gain experience. It explains how reflection converts real patient learning into capability and identity. It identifies desirable features of learning environments. This Guide advises clinicians, students, placement leads, faculty developers, and other stakeholders how to make new doctors as capable as possible. ExBL is a comprehensive model of medical students’ practice-based learning, which complements competency-based education to prepare new doctors to deliver safe, effective, and compassionate care.

Importance of the topic to international medical education

This Guide addresses medical students’ learning from supervised experience in practice settings. Opportunities to gain such experience are changing rapidly. There are more students and more specialties. Clinical practice is becoming ever more technical, its intensity is increasing, and work hours are reducing. Students have shorter attachments to fragmented teams, making it difficult for them to integrate into practice. Meanwhile, the patient safety agenda has made healthcare systems less accepting of students delivering care. A drive to quality-assure competence before students take responsibility for patient care has moved curricula to competence-based (or outcome-based) medical education (CBME) and assessment (Harden et al. Citation1999). At the same time, simulation has become a dominant part of the medical education landscape. These trends have led some people to question the importance of practical experience.

Training and assessing students is not sufficient to make them capable clinicians because context matters every bit as much as content. Scholars of workplace learning estimate that practitioners acquire over 80% of their knowledge “on the job”. The skill set they acquire is called capability, which is more adaptive but less easy to standardize than competence. (Neve and Hanks Citation2016) On-the-job learning has an inescapably important place in medical education.

Practice points

“Clinical teaching for the 21st century” is not about teaching: it is about supporting students’ learning from real patients within clinical practice

The skill of facilitating ExBL is to help students step outside their comfort zones without striding so far that they are a danger to themselves and others

Participation doesn’t just happen: students rise to the challenges of participating in practice in welcoming, well-organized learning environments where clinicians share their expertise

In summary, supported participation in practice resulting in real patient learning equips medical students with the identity and capabilities of safe, effective, and compassionate doctors, who can continue to learn lifelong

To become capable, learners need to feel psychologically safe. They must not feel too safe, though, because they learn by stepping outside their comfort zones. It is relatively easy, in simulated training environments, to adjust the level of psychological safety so that learners experience just the right balance of challenge and support. Practice-based learning is different because patient care poses unpredictable challenges, which can abruptly turn a safe situation into an unsafe one and vice versa. ExBL helps students learn in practice by defining in fine detail how clinicians can balance challenge and safety, on the fly, to the mutual benefit of students and patients. It helps students make the most of any contact time with patients and clinicians in any type of curriculum.

Aims and objectives

The aim is to provide clinicians with practical answers to the question: “How should I teach medical students when they are placed on my unit, during the procedures I perform, on our ward, or in my consulting room?” To achieve that aim, the objectives are to provide practical guidance about how:

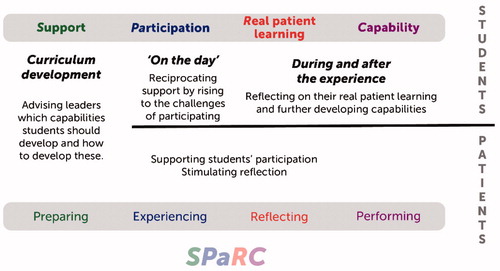

Medical students can participate in practice;

Members of the clinical workforce and patients can support students’ participation;

Clinicians can help students learn reflectively from real patient experience;

This leads to the capability and identity of a safe, effective, and compassionate doctor.

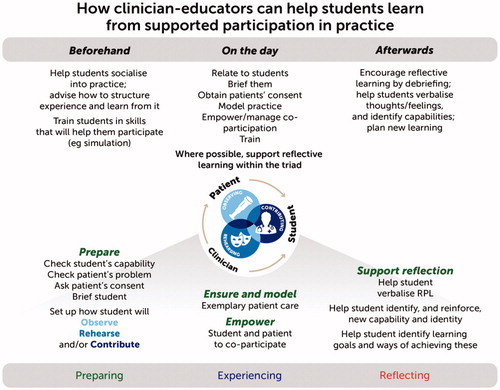

Readers who are impatient for answers to the questions above may wish to turn directly to and . Those who would like to understand principles as well as practice will find explanations for what we recommend in the next section.

Table 1. Affective capabilities.

Experience based learning (ExBL)

The Experience based learning (ExBL) pedagogy is the product of 20 years of work, surveying workplace learning theory, extracting evidence from nearly 300 published articles, conducting a program of research, and publishing a series of articles.

illustrates ExBL, according to which students need to have established the foundations of a doctor’s identity in order to perform as new doctors. To lay these foundations, students need to develop capability. Real patient learning (RPL), which results from reflection on experiences of participating within the triad of clinician, patient and student, equips them with capability. Clinicians’ supportive behavior creates the conditions for participation, RPL, and the development of capability. Clinicians: (1) model good practice and engage students into its provision; (2) encourage students to extend their current capability; (3) empower patients to co-participate in students’ learning. Clinicians engage students into workplace conversations, help them interact with patients receiving clinical care, and support their reflection on experience. SPaRC summarizes ExBL: Support; Participation; Real patient learning; Capability. The all-embracing outer arrows in emphasize that support is a core condition for ExBL.

The scope of ExBL

In scope: activities whose conjoint purpose is direct patient care and student education.

Not in scope: high stakes assessment; simulation.

Capability

Experience gives graduates three types of capability: intellectual (knowing), practical (being skilled), and affective (feeling), each of which has subtypes. The types of capability have fuzzy boundaries because they are complex, individual, different on different occasions, overlapping, and evolving throughout clinical life. The labels we use are archetypes rather than definitions that precisely distinguish one (sub-) type of capability from another.

Intellectual capability

The knowing that results from reflecting on experience and real patient learning is an integrated understanding of how to become and be a doctor, the contexts in which doctors practise medicine, and how practice is organized. Its subtypes are applied knowledge and reasoning skills.

Practical capability

This is a set of observable behaviors: clinical skills (behaviors that directly affect patients) and self-management skills (behaviors that help students and doctors organize their work and learning).

Affective capability

Affective capability includes values and emotions. This is important because graduates need to feel they are doctors and relate emotionally to others and their work. It is not primarily an observable behavior but does influence behavior. The subtypes are mood (e.g. satisfaction, reward, anxiety, anger), confidence and motivation, identity (e.g. feeling you are becoming a doctor, that you belong in clinical settings, and that you have the right to care for patients), attitudes and values (e.g. being idealistic, respectful, collaborative, and having a sense of responsibility), and affects towards others (e.g. empathy, compassion). Affective capability has traditionally been underemphasized; elaborates it.

Table 2. Supporting participatory learning.

Participation

Supported experience of participating in practice helps students become capable doctors. Students participate as members of the triad of patient, clinician, and student. There are three types of participation:

Observing: being present at and learning from practice without being hands-on involved.

Rehearsing: performing tasks of practice without contributing to patient care.

Contributing: being given responsibility to (co-)perform tasks of practice.

Observing, rehearsing, and contributing are rungs on a ladder that leads to independent practice. Students’ ascent of the ladder is anything but linear, partly because possibilities for participation vary greatly, and sometimes very fast, as dictated by patients’ clinical needs. explains how clinicians promote participation.

Observing

Observing is a rung on the ladder, which students must step onto because it gives them the breadth of experience and is a precursor to being active participants in patient care, but they should not linger there too long. It is most useful, when clinicians use techniques listed in , to make students active rather than passive observers.

Rehearsing

lists a range of activities that allow students to go through the motions of being a doctor, in context, without taking responsibility or contributing to a patient’s care.

Contributing

The top rung is making some hands-on contribution to patient care, no matter how small. This must, of course, be safe so it is influenced by students’ capability and the nature of patients’ problems. Students learn best when they are involved at the highest level; their capability allows them to make as complete a contribution as possible.

The dynamics of participation

Clinical workplace learning is dynamic by nature so clinicians need to respond dynamically, maintaining a level of participation that gives students the most educative amount of challenge. That means giving students slightly harder tasks and slightly more freedom to perform the tasks than the student might expect whilst making it clear that they are legitimate, their learning is important, and both they and patients will be safe. This comes more naturally to some clinicians than others. The following and the implications section, give practical tips.

Real patient learning

RPL is the reflective process by which students link prior learning to memorable patients and restructure, consolidate, reinforce, and contextualize what they have learned into nascent capabilities. Reflecting on experiences of participation helps students understand the scope and complexity of illness and disease and link theory with practice. The more experience and RPL the students have the better, because this builds up the repertoires of mental images and schemas on which doctors rely. RPL thrives on clinicians supporting students’ reflective learning in ways that are listed in . Above all, clinicians must listen well and judiciously prompt students to talk about their whole kaleidoscope of experiences.

Table 3. Examples of RPL that turn experience into capability.

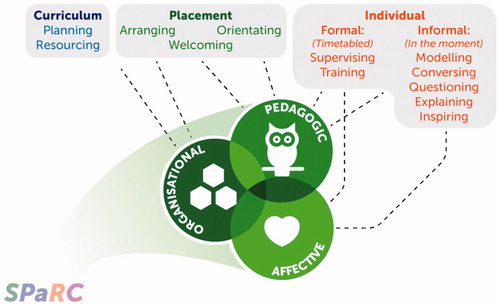

Support

Three conditions help students step out of their comfort zones and co-participate with patients and clinicians. The conditions are the same whether the experience is a placement, clerkship, preceptorship, clinical visit, elective, or internship, and whether this lasts for fleeting moments, months, or years. There are three types of support:

Organizational: facilities, resources, and the organization of students’ experiences.

Pedagogic: clinicians’ formal and informal support of students’ learning.

Affective: the display of positive attitudes and values in students’ learning environments.

Support is not mollycoddling students and it is not an optional extra. It enables students to rise to the challenges of practice. illustrates it and in the full Guide gives more detail.

Organizational support

This brings students, patients, and clinicians together so that clinical practice and education proceed alongside one another to the greatest benefit of all three parties. Clinicians’ leadership, which fosters three-way interactions between themselves, patients, and students, is the most important component of organizational support.

Pedagogic support

ExBL uses the phrase “formal pedagogic support” in preference to “teaching” to refocus the process on students rather than teachers and emphasize its supportive rather than didactic nature. This means modeling good practice, engaging students into clinical activities, and advising them how to structure and learn from their experiences. Clinicians provide informal support by thinking out loud, helping students think along with them, explaining, asking questions, listening, and conversing about practice. Clinicians help students, reflectively, turn participation into real patient learning and capability.

Affective support

Clinicians provide essential support by having positive attitudes towards educational and clinical practice and relating positively to students at group and individual level. Affective support is hard to define but easy to recognize. Whilst it is most easily observed in personal interactions between students and clinicians, it exists at all curriculum levels because being affectively supportive towards students makes placement and curriculum leaders most effective.

Evaluating ExBL

Well-designed learning environments help students find energy within themselves to learn. There are various ways of evaluating how well placements do this, all of which ask students to rate items on numerical scales. The Manchester Clinical Placement Index (MCPI) was developed specifically to evaluate ExBL (Dornan et al. Citation2012). It is short (just eight items) and invites students to write comments, which can suggest ways of improving placements. Despite being simple for students to complete, MCPI has at least as good reliability as an alternative widely used scale (Kelly et al. Citation2015). The mean of five of MCPI’s eight items measures the quality of the learning environment and the other three items measure the support given to students’ rehearsing and contributing. MCPI is a logical first choice for evaluating ExBL.

Pitfalls and solutions

Not all clinicians have positive attitudes towards students’ education and not all are capable of making ExBL work well. Clinical practice can be demanding at the best of times, which can make it hard for clinicians to balance patient care and student education. Not all patients are willing for students to participate in their care, which may be more of a problem in private than public healthcare. Students may find it difficult to adapt to learning environments, particularly when they rotate between different ones. ExBL addresses students’ passivity by transforming them from burdensome bystanders into (potential) contributors to healthcare teams. The Guide suggests how faculty development could help clinicians give extra support up-front, which encourages students to take responsibility for their learning and participate actively in practice. It suggests, also, how to help patients co-participate. Quality improvement also has an important part to play. Educators wishing to optimize ExBL can evaluate and adapt it to local circumstances and resources.

Implications

Implications for clinicians

Our answer to the question “How should I teach medical students when they are placed on my unit, during the procedures I perform, on our ward, or in my consulting room?” is this: “Support students’ participation in clinical practice; help them step outside their comfort zones, learn reflectively from doing so, and become more capable.” Your most important contribution may be informal and apparently small: such as being willing to relate to a student. Model good practice, engage students in conversation, ask them questions, explain what you are doing and inspire them to follow your example. Make clinical placements supportive by welcoming students, orientating them to clinical learning environments, and arranging relevant clinical learning opportunities. Exercise leadership and take an active interest in your curriculum.

Clinicians following ExBL principles empower students and patients to be active participants in practice-based learning, which is a far cry from “teaching by humiliation.” Another big difference from traditional clinical teaching is that the subject matter of students’ learning is always closely related to practice rather than arcane knowledge. ExBL stays within the “messiness” of real practice, where “right answers” are often conspicuously absent and courses of action are chosen collaboratively between patients and those who care for them.

lays this out this advice along the timeline of a short encounter between a clinician and a student and and specify many different ways of putting this advice into practice.

Table 4. Making placements supportive.

Patients’ and students’ involvement

Patients’ main contribution is to co-participate with students during clinical encounters. Students’ main contribution is to build relationships with clinicians, participate actively in practice, learn reflectively, and develop their capabilities as a result of this. Patients and students may, in progressive curricula, contribute to curriculum development ().

Implications for placement leaders

Leadership is a key to the success of clinical placements. Leaders provide organizational, pedagogic, and affective support, but may do so at arm’s length rather than at the individual level.

Key questions for placement leaders to answer are:

What opportunities to participate can this placement offer?

What capabilities can students develop from those opportunities?

How can we support students’ participation and development of those capabilities?

lists a set of answers to those questions.

Implications for curriculum leaders and faculty developers

The full Guide contains these.

Conclusions

ExBL takes it as an axiom that medical students are preparing to start work as doctors and that, to be able to work, students need experience of work. To accommodate the various curriculum designs and affordances for participatory learning that exist in different countries, ExBL provides a theorized, evidence-based set of principles that can be applied flexibly in different contexts. Perhaps even to residency and other health professions. Our advice to clinicians wanting to be better “clinical teachers” is to use the SPaRC acronym: Support students’ Participation, reflective Real patient learning, and development of the Capabilities and identity of a doctor-to-be.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Glossary

Capability:

Practical capability: Being capable of performing doctors’ tasks, including learning in/from practice.

Intellectual capability: Having practically useful knowledge and being able to apply this.

Affective capability: Having emotions, attitudes and values that make a doctor capable.

Experience: Authentic (real as opposed to simulated) human contact in a clinical context that enhances learning of health, illness and/or disease and the role of health professionals.

The patient may be present by proxy [e.g. a student may discuss their X-ray with a doctor] but they must be real, not simulated. Provided the student is in direct personal contact with the patient and is learning within a supportive practice community, the doctor may be present by proxy.

Experience-based Learning (ExBL): Gaining real patient experience as a result of supported participation in practice within the triad of doctor, patient, and student, which results in a student developing the capabilities and identity of a doctor.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with deep gratitude the contribution of our international panel of advisors, which included Drs: Mohammed Al-Eraky, Julia Blitz, Joseph Daka, Eduardo Durante, Louise Dubras, Tony Egan, Mall Eltermaa, Ajandek Eory, Walter Eppich, Zac Feilchenfeld, Harumi Gomi, Esther Helmich, Ibrahim Inuwa, John Jenkins, Takeshi Kimura, Stefan Kutzsche, Annalisa Manca, Walther van Mook, Hiroshi Nishigori, Brett Schrewe, Susan van Schalkwyck, Pia Strand, Pim Teunissen, Susan Wearne, Tim Wilkinson, and Huei-Ming Yeh.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tim Dornan

Tim Dornan, MA, DM, FRCP, MHPE, PhD, is an internist and endocrinologist who completed a Masters and PhD in medical education at Maastricht University. His primary methodological interests are qualitative and implementation research. He is Professor of Medical Education at Queen’s University Belfast and Emeritus Professor, Maastricht University. He wrote this article.

Richard Conn

Richard Conn, MB, BCh, MRCPCH, is a trainee pediatrician and PhD student, investigating how doctors make errors in prescribing for children. He researches students’ and doctors’ learning in workplaces and how knowledge about this can promote safer practice. He led the literature review and contributed to writing this article.

Helen Monaghan

Helen Monaghan, BSc (Hons), graduated in Human Biology in 2016 and is currently a third-year medical student at Queen’s University Belfast. She conducted the literature review and contributed to writing this article.

Grainne Kearney

Grainne Kearney, MB, BCh, MRCGP, MSc, is a practising General Practitioner, PhD candidate, and lecturer-elect in medical education. She completed a Masters in Clinical Education in 2014. Her academic interests include Institutional Ethnography, critical research into OSCEs, and promoting praxis in medical education. She contributed to reviewing the literature and writing this article.

Hannah Gillespie

Hannah Gillespie, BSc, MB, BCh, qualified as a doctor in 2018, having received many awards for leadership and innovation. She completed an intercalated BSc in Medical Education, from which she published two research articles and is now an Academic Foundation Trainee, where she continues to research medical students’ workplace learning. She contributed to the literature review and writing this article.

Deirdre Bennett

Deirdre Bennett, MB, MPH, MA, PhD, is Head of the Medical Education Unit and Director of the 5 Year MB program at University College Cork. Her clinical background is in General Practice. Her research interests include professional identity formation, clinical learning environments, and regulation of professional competence. She contributed to reviewing the literature and writing this article.

References

- Dornan T, Muijtjens A, Graham J, Scherpbier A, Boshuizen H. 2012. Manchester Clinical Placement Index (MCPI). Conditions for medical students’ learning in hospital and community placements’. Adv Health Sci Educ. 17:703–716.

- Harden RM, Crosby JR, Davis MH. 1999. AMEE Guide No 14: outcome-based education: Part 1 - An introduction to outcome-based education. Med Teach. 21:7–14.

- Kelly M, Bennett D, O’Flynn S, Dornan T. 2015. Can less be more? Comparison of the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) and a novel 8-item placement quality measure. Adv Health Sci Educ. 20:1027–1032.

- Neve H, Hanks S. 2016. ‘When I say … capability’. Med Educ. 50: 610–611.