Abstract

Situational tele-mentorship refers to the use of technology to provide interactive, two-way communication between an advisor (the mentor) and a novice (mentee) to enhance the management of a dynamic clinical scenario in real-time.

This article develops a conceptual framework to support situational tele-mentorship of healthcare professionals working in rural and remote practices by critically exploring the concept of mentorship within medical education literature and applied to healthcare professionals working in more isolated settings.

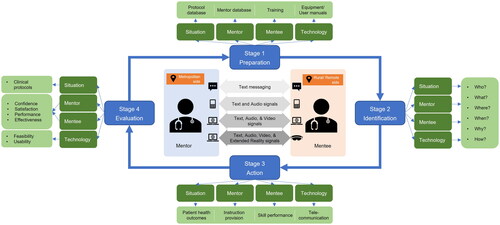

The situational tele-mentorship framework consists of synchronous telecommunication technologies and the problem-solving process. The end-users of the framework are the mentor located centrally and the mentee dealing with a challenging situation at a remote location using communication technology. The problem-solving process’ stages are preparation, identification, action, and evaluation. The mentor and mentee use the 5W1H model, which is a summary of the questions of who, what, where, when, why, and how, applied in two-way communication.

This framework provides medical teachers and clinicians with a detailed, yet concise exposition of critical elements required to implement situational tele-mentorship. Healthcare providers can also use this framework to help coordinate resources and manage stakeholders in tele-mentoring situations.

Introduction

Rural and remote communities in Australia have poorer health outcomes, increased hospital admission rates, higher chronic disease, higher cancer rates, lower life expectancy and higher mortality rates than their city counterparts (Rural Health Standing Committee Citation2011; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Citation2016; Australian Department of Health Citation2022). Residents in remote areas of Australia have the highest healthcare needs but can lack access to health services with the lowest number of health professionals per capita (Health Workforce Australia Citation2012; National Rural Health Alliance Citation2016). There has been a continued shortage of both general practitioners (GP) and non-GP specialists in rural and remote areas, with less than 5 per cent of most non-GP specialists based in these areas (Australian Department of Health Citation2019, Citation2022). The proportion of GPs working in remote and very remote areas declined by 0.1% from 2014 to 2019 (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Citation2020).

Practice points

Situational tele-mentorship refers to a long-distance relationship in which an experienced professional using telecommunication technologies provides guidance and assistance to a less-experienced practitioner to deal with a specific challenging situation in real-time.

Establishing effective situational tele-mentorships will help improve the clinical skills of the rural healthcare workforce and may contribute to retaining skilled health practitioners in isolated areas.

The proposed framework provides medical teachers and clinicians with a detailed yet concise method for conceptualising and implementing situational tele-mentorship.

Health service providers can use the proposed framework to plan and coordinate resources to manage stakeholders in tele-mentoring situations.

Many rural practitioners and specialists spend time travelling to consult patients at widely dispersed locations. Consequently, they have a higher workload and may have less time available to spend with patients. Rural and remote practitioners often have a broader scope of practice that enables them to deliver comprehensive care to people with poorer health status and across a wider range of health needs (National Rural Health Alliance Citation2013). Doctors, midwives, nurses and allied health workers in many small remote communities frequently experience long working hours and can be expected to respond to a range of medical emergencies (National Rural Health Alliance Citation2016). These issues contribute to the challenge of delivering effective health services and the difficulties in attracting and retaining appropriately skilled healthcare professionals in these areas (George et al. Citation2018).

In 2010, the World Health Organization (Citation2010) called for rural and remote mentorship opportunities to help recruit and retain healthcare professionals in these areas. In Australia, the 2019 scoping framework for the national medical workforce strategy (Australian Department of Health Citation2019) suggested that mentorship may be one strategy that could help address the geographic maldistribution of health workers and inequalities in healthcare access across the rural/remote-urban divide. Research suggests that mentorship can be used as a mechanism to help retain healthcare professionals in rural and remote settings (Mills et al. Citation2005; Curran et al. Citation2008; Rohatinsky and Ferguson Citation2013; Bourke et al. Citation2014). Rural healthcare professionals were more likely to stay in rural areas if they were connected through peer support networks, had relationships with colleagues in urban centres and had the means to communicate electronically with others (Conger and Plager Citation2008). The establishment and maintenance of mentoring relationships can support novice healthcare staff to meet the challenges of rural healthcare environments (Mills et al. Citation2005; Scott and Smith Citation2008) and assist with the transition to working in a rural healthcare facility by helping alleviate feelings of isolation (Rohatinsky and Jahner Citation2016). Mentors can be a source of knowledge, available to respond to questions, and provide guidance, direction, and decision-making support. It has been reported that mentoring is a crucial component of an effective orientation process, reducing professional isolation, supporting the transition of new international medical graduates to medical practice, and enhancing the integration of these graduates and their families within their new communities (Curran et al. Citation2008).

This article develops a conceptual framework to support situational tele-mentorship in rural and remote practices. It describes the concept of mentorship and how mentorship can be provided remotely using technological communication devices.

Mentorship

The term mentoring originates from Greek mythology, the Odyssey, where Odysseus entrusts his son to the care of Mentor, his old trusted friend, before fighting in the Trojan War (Colley Citation2002). The mentor helped the boy grow up and saved his life on occasion.

By reviewing 40 different definitions used in the empirical literature since 1980, Haggard et al. (Citation2011) determined ‘mentoring’ to be an interpersonal exchange between a mentor, or a senior experienced person, and a mentee, the less experienced junior person.

In a mentoring relationship, a mentee has the ultimate responsibility of actively determining their needs from the mentoring relationship and seeking support and guidance for their career and professional development. A mentor helps the mentees articulate and define their professional goals and then uses a facilitative approach to enable the mentee to achieve these goals. Mentorship is based upon mutual trust, respect, openness, encouragement, constructive feedback, and a willingness to learn and share. Unlike traditional training relationships, mentorships are more interactive and emphasise two-way communication. In a mentoring relationship, a mentor who serves as an advisor, exemplar or host; provides support, direction, and feedback to a novice mentee to enhance the proficiency and independence of the mentee and aid in their career advancement (Bozeman and Feeney Citation2007; Nakamura et al. Citation2009; Alred and Garvey Citation2019).

Mentorship in rural and remote settings

Mentoring relationships may support practitioners who work in rural and remote settings who experience more generalist scopes of practice, a close connection with local communities and isolation from specialist care and professional support (Bourke et al. Citation2004; Liaw and Kilpatrick Citation2008). Studies have identified aspects of rural and remote practice that encourage or discourage mentoring (Rohatinsky and Ferguson Citation2013; Bourke et al. Citation2014; Rohatinsky and Jahner Citation2016; ).

Table 1. Enablers and barriers of mentorship in rural and remote settings.

Other reports point to budget constraints and limited access to mentor resources inhibit managers’ abilities to establish mentorship arrangements for employees (Curran et al. Citation2008; Rohatinsky and Ferguson Citation2013). In many rural facilities, staff members frequently work in isolation or with minimal interaction with staff from different disciplines. This can challenge managers’ ability to pair up employees of the same discipline for mentorship. Short-term contracts for staff working in rural and remote areas can also frustrate efforts to pair up staff. It has been suggested that offering permanent positions, finding stable housing, developing social relationships with other staff members and establishing community networks may enable new staff to be mentored more effectively and also be retained within the workforce (Curran et al. Citation2008).

To address some of the challenges in providing mentorship and support to the health workforce in rural and remote areas, tele-mentorship has been seen as a possible solution due to its widespread accessibility and potential to overcome the barriers of distance and geographical separation. Petridou (Citation2009) has suggested that technology can aid mentoring in rural and remote settings, where remoteness and isolation can make communication more difficult. Tele-mentorship is a type of mentorship in which a mentor interactively guides a mentee at a different geographic location using a technological telecommunication device. During a healthcare procedure, for example, tele-mentorship can be used by an expert located in a major hospital to provide instruction in real-time to a less-experienced practitioner located at a rural treatment site (Agarwal et al. Citation2007).

However, the term ‘tele-mentorship’ may not completely describe the relationship that occurs in some clinical situations in rural and remote areas where urgent advice and support are required in real-time (Bracale et al. Citation2002; Martiniuk et al. Citation2011). This includes rural emergency facilities, where staffing is limited, the workload is unpredictable, and a wide range of patients present for care and treatment. Novice and more junior staff especially need support from experienced experts to address the unknown and unexpected, including medical emergencies, the application of medical devices they may not be familiar with (Drew et al. Citation2006; Oldenburg et al. Citation2012), disaster situations (Wani et al. Citation2013), during military action (Wilson et al. Citation2013), on transportation such as aircraft, boats and trains (Amenta et al. Citation1998; Ferrer-Roca et al. Citation2002; Weinlich et al. Citation2009), and also in some home care situations (Silver et al. Citation2004; Romano et al. Citation2010). The mentor-mentee interactions in such situations are characterised by immediacy, situational awareness, highly contextualised communication, and real-time Tele assistance and are conducted over a short period. The effectiveness of this relationship is underpinned by the professional expertise (of the mentor) as well as technical proficiency in the use of the telecommunication device by both the mentor and the mentee (Clement and Welch Citation2017). The essential elements of this type of mentoring relationship are captured by the term situational mentorship.

As one of few authors to draw attention to the term situational mentorship, Emelo (Citation2010) defined it as ‘a quick-hitting, short-term collaborative learning relationship that stimulates creative solutions’. The author stated that as with traditional mentoring, mentees in situational relationships engage with mentors for guidance and feedback. However, unlike long-term traditional mentorships, mentees seek assistance from those who can provide specific instruction on a high-impact problem, issue, challenge, or opportunity that requires a quick resolution. These engagements are quick to set up and shut down. The United States Office of Personnel Management (Citation2008) described the situational mentoring period as typically short, though noted that it could transition to a more long-term connection. Gray (Citation2012) further elucidated the concept and developed a six-step process for situational mentoring that involved: (1) understanding a mentee’s needs, goals, attitudes, and perception; (2) realising actions and consequences; (3) identifying a mentee’s real issue; (4) developing productive goals, attitudes, and perceptions; (5) expanding a mentee’s thinking to consider new options; and (6) agreeing on a workable plan to handle a mentee’s situation.

In rural and remote settings situational mentorship often draws upon telecommunication technology such as smartphones and augmented reality devices to connect the mentor and mentee. In many circumstances, face-to-face meetings are simply not possible. Our search of the published research and the grey literature failed to yield evidence of where situational mentorship had been purposively discussed or conceptualised in direct association with tele-mentorship. Given the emerging use and importance of this area, especially to support a widely dispersed rural and remote workforce, we coined the term “Situational Tele-Mentorship” to explore how this concept could be framed and described to inform future applications and to assist in the evaluation of a mentoring relationship that is situational and mediated by telecommunication technology.

Situational Tele-Mentorship

We propose that Situational Tele-Mentorship (STM) in health environments is a long-distance relationship in which an experienced professional using telecommunication technologies provides guidance and assistance to a less-experienced practitioner to deal with a specific challenging situation in real-time. The aim is to transfer knowledge and skills from the mentor to the mentee and to jointly determine how progress and success can be monitored and evaluated.

Relationship

A situational tele-mentoring relationship primarily focuses on mentoring between one mentor and one mentee. This form of mentoring works well for practitioners in rural/remote areas where parties know each other or have had the opportunity to establish the relationship before the tele-mentoring situation so that the skills and knowledge of both mentor and mentee are understood through a relationship that has already been established. This mentorship is also time-limited, so appropriate for busy mentors and mentees who also have other commitments and professional responsibilities.

Mentor

In a situational tele-mentorship, the mentor will likely be senior, knowledgeable, well-respected, and have experience relevant to the situation happening at the mentee’s location. The minimum criteria for mentor selection are that the mentor should be seen as an expert by peers and be willing to handle the many responsibilities associated with the mentoring role. Similar to a mentor in a situational mentorship (Clutterbuck et al. Citation2017), the role of the mentor in STM may include:

An advisor and sharer of professional knowledge and experience.

A coach who asks questions that provides the mentee with new insights and new perspectives on a situation.

A discussion partner who can challenge the mentee about assumptions, opportunities, and solutions.

A critic who provides the mentee with constructive criticism and feedback.

Unlike traditional mentorship, a mentor in an STM relationship is not a storyteller, networker, door opener, or sponsor. This is because the focus of an STM is to solve specific issues the mentee is facing in real-time. There is less chance for both parties to tell life stories or to provide the mentee with career visibility as would be expected of a long-term mentoring relationship.

Mentee

Although mentees are less experienced, they must be competent to deliver professional services within their scope of practice and possess at least some of the skill components required for the task at hand. The mentor is not at the scene and therefore unable to intervene directly to assist the mentee physically.

Telecommunication

Face-to-face meetings do not occur in a situational tele-mentorship. Rather, real-time meetings using telecommunication technologies are used to enhance the telepresence of the mentor in a timely way in the mentee’s field of activity. The mentor-mentee communication is synchronous when both parties are present at the same time. Interactive two-way communication is essential to allow for real-time responsiveness. There should be a level of comfort and confidence in using the technology and acceptance that face-to-face communication is not a fallback option. Without this, frustrations can escalate and impact the effectiveness of the relationship.

Situation

In the context of health environments, ‘situational’ in a situational tele-mentorship refers to the environment or activity space in which healthcare interventions, clinical treatments, or medical practices are delivered by the mentee. ‘Situational’ also refers to the responsibility of the mentor to be on hand, contextually aware and, responsive to the mentee’s needs.

Gray (Citation2012) suggested that situational factors be taken into account include the:

urgency of the situation that requires the mentee to act immediately.

mentee’s relevant experience pertinent to the situation.

mentee’s current awareness of factors (actual and potential) impacting the situation.

critical nature of the situation, and the risk/reward of possible interventions.

mentee’s current competence or ability to do what is required for success.

mentee’s attitude toward and perception of the situation (positive or negative).

Situational Tele-Mentorship framework

‘Situational Tele-Mentorship’ refers to a mentoring relationship that is situational and mediated by telecommunication technology. As a new construct, further development and testing of its hypothesised components and application is aided by a conceptual framework or model. The core components of the model are the end-users, synchronous telecommunication technologies and a problem-solving process (Knop and Mielczarek Citation2018). Two targeted end-users in the framework are the mentor located, for example, at a major metropolitan hospital and the mentee dealing with a challenging situation at a remote, rural location. They use technology to communicate with each other in real-time ().

Synchronous telecommunication technologies provide various options for two-way interactivity over long distances (Parsons Citation1997). This includes text messaging (i.e. pager, mobile phone), audio connection (i.e. telephone, mobile phone), audio and video connection (i.e. videophone, smartphone, video teleconferencing system), and extended reality (i.e. augmented reality devices). Text messaging or voice calls is still the primary method of communication in some remote areas, though this can make it more difficult to establish trust and confidence between mentors and mentees, particularly when the parties have never met or seen each other (Clutterbuck and Lane Citation2016). Encouragingly, audio-visual technology has evolved to the point of enabling meaningful two-way interaction. This technology can be used to lower the burden on expert mentors and improve access (Brown Citation2015). As a relatively recent technology, Extended Reality (xR) refers to all real-and-virtual, mixed environments and human-machine interactions generated by computer technology and wearable devices such as smart glasses, xR encompasses Virtual Reality (VR), Mixed Reality (MR), and Augmented Reality (AR). The levels of virtuality range from partial sensory inputs (AR) to immersive virtuality (VR).

In the model, the problem-solving process has four stages: (1) Preparation; (2) Identification; (3) Action; and (4) Evaluation. The preparation stage establishes the foundation for an effective professional relationship (Brockbank and McGill Citation2006) and may positively impact health outcomes (Brown Citation2015). Drawing on Kajs’ work (2002), the STM framework recommends developing a pool of prospective mentors, consisting of experienced healthcare professionals who meet relevant selection criteria. Kajs (Citation2002) also recommended designing a job description for the mentor that outlines their roles and responsibilities, as well as a list of the resources available to support the mentoring role. In addition, potential mentors with specific expertise and experience can be identified using technical and local networking groups, mailing lists or online resources. In healthcare environments, sharing incorrect information (or omitting information) can be life-threatening or harmful to patients. Ong and Coiera (Citation2011) review of the incident and complaint data reported strong evidence of the critical impact of a lack of appropriate communication on adverse medical events. Therefore, the telecommunication protocols should be standardised and disseminated to facilitate effective communication between the mentor and the mentee (Box 1).

Box 1. 5W1H approach in stage 1.

Objective: Ensure the readiness of mentors and mentees before the given situation.

Who are qualified to be potentially the mentors in rural and remote settings?

Who are the potential mentees in rural and remote healthcare environments?

What are the potential mentees and mentors trained before the given situation?

What are the potential mentees and mentors equipped before the given situation?

What will be used to improve the telepresence of the mentor at the remote scene?

How to protect the personal identification information of the patient once using telecommunication technologies?

What are the standardized clinical protocols of the mentee-mentor telecommunication in critical care cases?

In Stage 2 of the framework (identification), the mentor and mentee can use the ‘5W1H’ model (who, what, where, when, why, and how) to describe a situation. Since these questions are all open, they can prompt a more focused and relevant conversation between the parties. Although the 5W1H model itself does not solve a situation, it does enable a more holistic picture of the situation to be communicated (Emelo Citation2010). Both parties need to understand the situation within the actual context and its possible consequences. The situation statement provided by the mentee must include detailed information for the potential mentor to make a quick judgement as to their desire or ability to help. Providing a clear and concise description of the context also serves as a good starting point to decide on the actions that will need to be taken (Box 2).

Box 2. 5W1H approach in stage 2.

Objective: Identify the situation and available options for potential remote assistance.

What is the situation?

Where does the situation arise?

When does the situation arise?

Why does the mentee need support from the mentor?

Who will be the best mentor in the situation?

How does the mentee connect to the mentor remotely?

In stage 3 (Action), the mentee and mentor draw on information about the situation to allow for a plan of action determined and implemented. This may also require additional data to be sourced (patient records, clinical protocols or best practice guidelines for example) and instruction on specific interventions such as procedural skills. The mentor and mentee jointly decide when to end the interaction once the goal is reached or changed, according to the patient’s health care outcomes (Box 3).

Box 3. 5W1H approach in stage 3.

Objective: Communicate with the mentor to address the situation.

What do the mentor and mentee need to do to handle the situation?

How to share the context of the situation in the most vivid manner?

How does the mentor instruct the mentee remotely?

How does the mentee follow the mentor’s instruction remotely?

How to record the scenario for further management and training purposes?

Situational tele-mentorship is a multifaceted endeavour. Once the patient-centred action stage has been completed, the mentor and mentee can determine when and how to evaluate the success of their interaction. This Stage (Evaluation) may include an assessment of satisfaction with and performance of each party, as well as the effectiveness of the relationship and its impact on the situation and patient outcomes. Telecommunication technology may be reviewed to identify its strengths and weaknesses as well as areas that could be improved. Data from this stage would then feedback to the preparation stage (Box 4).

Box 4. 5W1H approach in stage 4.

Objective: Assess the situational tele-mentoring progress and explore further requirements.

What has been achieved?

What are future mentoring and training requirements?

How well is the relationship going?

Discussion

The situational tele-mentorship framework has been developed to examine mentorship that uses telecommunication technology to provide tele-assistance in real-time. Communication technologies are evolving rapidly. The telephone has largely been replaced by more sophisticated devices that feature visual as well as audio modalities. As an emerging telecommunication technology, Augmented Reality (AR) has been used for remote guidance and instruction on the performance of technical tasks, complex assembly, disruptive tasks and skills training (Regenbrecht et al. Citation2005). This technology can, potentially, enhance the effectiveness of tele-mentorship in dealing with challenging clinical health care delivery situations in real-time. Using an AR device, the mentee can share their real-time view at a remote location with the mentor. Meanwhile, the mentor can draw on e-data such as case files, treatment protocols and visual prompts, create annotations and transmit them directly into the mentee’s field of view, anchored to relevant areas of the actual operating field (Treter et al. Citation2013; Andersen et al. Citation2016). A systematic review by Bui et al. (Citation2021) revealed that the tele-mentoring systems using AR technology have been effective in providing guidance on the performance of clinical procedures. Benefits include improvements in mentees’ confidence, task completion time, and reductions in task errors and shifts in focus.

The introduction of new, technology base communication tools to the mentorship relationship can however confound the situation (Kochan and Pascarelli Citation2005). For example, devices break, Internet connections go down, or computers crash. These situations can degrade the quality of the relationship by making communication more difficult and increasing transactional distance. While it is unreasonable to expect mentor and mentees to be technological experts who can fix all glitches, there is a need to train mentors and mentees about the technologies, hardware, and software available to use in STM (Clutterbuck et al. Citation2017). A safe backup plan is suggested if either party is uncomfortable using technology or the procedure. Additionally, the willingness of mentors and mentees to use technologies is vital for a successful STM relationship, especially in urgent situations when support from technical teams may be unavailable.

Whilst the STM has been developed with AR technologies in mind, it can also be applied when other communication technologies are used.

For example, key components of the model are in evidence with the Real-Time Virtual Support pathways for healthcare providers in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities in British Columbia, Canada (Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. Citation2022). Rural healthcare providers, including physicians, physician residents, nurse practitioners, nurses, and midwives, can connect via Zoom or telephone with virtual physicians to access remote real-time clinical support. The rural providers have 24/7 access (Zoom contacts and phone numbers) for emergency, paediatrics, maternity, newborn, and other areas.

This framework was developed with a focus on the challenges rural and remote workers face when working in relative isolation without access to specialist advice and support. By following this framework, rural GPs and other health care practitioners can have greater confidence in exploring a broader and more extended scope of practice to address the health needs of the communities they serve. The framework also emphasises the significance of improving awareness and knowledge of using advanced technologies in tele-assistance between urban and rural practitioners. The STM framework provides a way to conceptualise and deliver tele-assistance to practitioners in rural and remote areas.

Conclusion

This article provides a new basis for further research and development in establishing effective situational tele-mentorships to improve the clinical skills of the rural healthcare workforce and retain skilled health practitioners working in isolated areas. Further studies are needed to test and evaluate the utility of the ‘situational tele-mentorship’ construct and to assess the impact of the framework in managing different types of ‘situations’ between different types of health care workers in both laboratory and clinical environments.

Glossary

Augmented Reality: Is a form of immersive experience in which the real world is enhanced by computer-generated three-dimensional content, which is tied to specific locations and/or activities.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dung T. Bui

Dung T. Bui, Centre for Rural Health, School of Health Sciences, College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia.

Tony Barnett

Tony Barnett, Centre for Rural Health, School of Health Sciences, College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia.

Ha Hoang

Ha Hoang, Centre for Rural Health, School of Health Sciences, College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia.

Winyu Chinthammit

Winyu Chinthammit, Human Interface Technology Laboratory, Discipline of ICT, School of Technology, Environments and Design, College of Sciences and Engineering, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia.

References

- Agarwal R, Levinson AW, Allaf M, Makarov DV, Nason A, Su L-M. 2007. The robo consultant: tele-mentoring and remote presence in the operating room during minimally invasive urologic surgeries using a novel mobile robotic interface. Adult Urology. 70(5):970–974.

- Alred G, Garvey B. 2019. The mentoring pocketbook. 4th ed. UK: Management Pocketbooks.

- Amenta F, Dauri A, Rizzo N. 1998. Telemedicine and medical care to ships without a doctor on board. J Telemed Telecare. 4(1_suppl):44–45.

- Andersen D, Popescu V, Cabrera ME, Shanghavi A, Gomez G, Marley S, Mullis B, Wachs J. 2016. Avoiding focus shifts in surgical telementoring using an augmented reality transparent display. Stud Health Technol Inform. 220:9–14.

- Australian Department of Health. 2019. Scoping framework for the national medical workforce strategy. Canberra: ACT.

- Australian Department of Health. 2022. National medical workforce strategy 2021–2031. Canberra: ACT.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2016. Australia’s health 2016. Canberra: ACT, AIHW.

- Bourke L, Sheridan C, Russell U, Jones G, DeWitt D, Liaw ST. 2004. Developing a conceptual understanding of rural health practice. Aust J Rural Health. 12(5):181–186.

- Bourke L, Waite C, Wright J. 2014. Mentoring as a retention strategy to sustain the rural and remote health workforce. Aust J Rural Health. 22(1):2–7.

- Bozeman B, Feeney MK. 2007. Toward a useful theory of mentoring: a conceptual analysis and critique. Adm Soc. 39(6):719–739.

- Bracale M, Cesarelli M, Bifulco P. 2002. Telemedicine services for two islands in the Bay of Naples. J Telemed Telecare. 8(1):5–10.

- Brockbank A, McGill I. 2006. Facilitating reflective learning through mentoring and coaching. London and Philadelphia: Kogan Page.

- Brown KM. 2015. Simulation in surgical training and practice, an issue of surgical clinics. 1st ed., vol. 95. Elsevier.

- Bui DT, Barnett T, Hoang H, Chinthammit W. 2021. Tele-mentoring using augmented reality technology in healthcare: a systematic review. Australas J EducTechnol. 37(4):68–88.

- Clement SA, Welch S. 2017. Virtual mentoring in nursing education: a scoping review of the literature. JNEP. 8(3):137–143.

- Clutterbuck D, Kochan F, Lunsford L, Domínguez N, Haddock-Millar J. 2017. The SAGE handbook of mentoring. UK: SAGE Publications.

- Clutterbuck D, Lane G. 2016. The situational mentor: an international review of competencies and capabilities in mentoring. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Colley H. 2002. A 'Rough guide to the history of mentoring from a Marxist feminist perspective. J Educ Teach. 28(3):257–273.

- Conger MM, Plager KA. 2008. Advanced nursing practice in rural areas: connectedness versus disconnectedness. OJRNHC. 8(1):24–38.

- Curran V, Hollett A, Hann S, Bradbury C. 2008. A qualitative study of the international medical graduate and the orientation process. Can J Rural Med. 13(4):163–169.

- Drew BJ, Sommargren CE, Schindler DM, Zegre J, Benedict K, Krucoff MW. 2006. Novel electrocardiogram configurations and transmission procedures in the prehospital setting: effect on ischemia and arrhythmia determination. J Electrocardiol. 39(4 Suppl):S157–S160.

- Emelo R. 2010. In practice situational mentoring: microlearning in action. Chief Learning Officer. 9(7):43.

- Ferrer-Roca O, Diaz D, Leon R, de Latorre F, Suárez-Delgado M, Di Persia L, Cordo M. 2002. Aviation medicine: challenges for telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 8(1):1–4.

- George EJ, Fredrick Clive W, Kirsty F. 2018. The impact of rural outreach programs on medical students’ future rural intentions and working locations: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 18(1):1–19.

- Gray WA. 2012. Situational mentoring. Mentoring solutions. https://www.mentoring-solutions.com/situational-mentoring

- Haggard DL, Dougherty TW, Turban DB, Wilbanks JE. 2011. Who is a mentor? A review of evolving definitions and implications for research. J Manage. 37(1):280–304.

- Health Workforce Australia. 2012. Health workforce 2025: doctors, nurses and midwives. Adelaide, SA: HWA.

- Kajs LT. 2002. Framework for designing a mentoring program for novice teachers. Mentor Tutoring. 10(1):57–69.

- Knop K, Mielczarek K. 2018. Using 5W-1H and 4M methods to analyse and solve the problem with the visual inspection process – case study. Paper presentation presented at 12th International conference quality production improvement – QPI 2018; Myszków, Poland.

- Kochan FK, Pascarelli JT. 2005. Creating successful telementoring programs. In: Kochan FK, editor. Perspectives on mentoring. Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing; p. 338.

- Liaw S, Kilpatrick S. 2008. A textbook of Australian rural health. Canberra, ACT: Australian Rural Health Education Network.

- Martiniuk A, Negin J, Hersch F, Dalipanda T, Jagilli R, Houasia P, Gorringe L, Christie A. 2011. Telemedicine in the Solomon Islands: 2006 to 2009. J Telemed Telecare. 17(5):251–256.

- Mills JE, Francis KL, Bonner A. 2005. Mentoring, clinical supervision and preceptoring: clarifying the conceptual definitions for Australian rural nurses. A review of the literature. Rural Remote Health. 5(3):410.

- Nakamura J, Shernoff DJ, Hooker CH. 2009. Good mentoring: fostering excellent practice in higher education. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- National Rural Health Alliance. 2013. How many doctors are there in rural Australia? Deakin West, ACT: ARHA.

- National Rural Health Alliance. 2016. The health of people living in remote Australia. Deakin West, ACT: ARHA.

- Oldenburg M, Baur X, Schlaich C. 2012. Assessment of three conventional automated external defibrillators in seafaring telemedicine. Occup Med. 62(2):117–122.

- Ong M-S, Coiera E. 2011. A systematic review of failures in handoff communication during intrahospital transfers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 37(6):274–284.

- Parsons CL. 1997. Communication technology as a means of empowerment. J Fam Stud. 3(1):67–92.

- Petridou E. 2009. E-mentoring women entrepreneurs: discussing participants’ reactions. Gend Manag. 24(7):523–542.

- Regenbrecht H, Baratoff G, Wilke W. 2005. Augmented reality projects in the automotive and aerospace industries. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 25(6):48–56.

- Rohatinsky N, Ferguson L. 2013. Mentorship in rural healthcare organizations: challenges and opportunities. OJRNHC. 13(2):149–172.

- Rohatinsky N, Jahner S. 2016. Supporting nurses’ transition to rural healthcare environments through mentorship. Rural Remote Health. 16(1):3637.

- Romano M, Cesarelli M, D'Addio G, Mazzoleni MC, Bifulco P, Ferrara N, Rengo F. 2010. Telemedicine fetal phonocardiography surveillance: an Italian satisfactory experience. Stud Health Tech Inform. 155:176–182.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. 2020. General practice: health of the nation 2020. East Melbourne, VIC: RACGP.

- Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. 2022. Real-time virtual support (RTVS). Vancouver, BC; https://rccbc.ca/rtvs/.

- Rural Health Standing Committee. 2011. National strategic framework for rural and remote health. Canberra, ACT: Australian Department of Health.

- Scott ES, Smith SD. 2008. Group mentoring: a transition-to-work strategy. J Nurses Staff Dev. 24(5):232–238.

- Silver HJ, Wellman NS, Galindo-Ciocon D, Johnson P. 2004. Family caregivers of older adults on home enteral nutrition have multiple unmet task-related training needs and low overall preparedness for caregiving. J Am Diet Assoc. 104(1):43–50.

- Treter S, Perrier N, Sosa JA, Roman S. 2013. Telementoring: a multi-institutional experience with the introduction of a novel surgical approach for adrenalectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 20(8):2754–2758.

- United States Office of Personnel Management. 2008. Best practices: mentoring. Washington, DC: United States Office of Personnel Management.

- Wani AR, Shabir S, Naaz R. 2013. Augmented reality for fire and emergency services. Proceeding of the International Conference on Recent Trends in Communication and Computer Networks. Vol. 7. p. 32–41.

- Weinlich M, Nieuwkamp N, Stueben U, Marzi I, Walcher F. 2009. Telemedical assistance for in-flight emergencies on intercontinental commercial aircraft. J Telemed Telecare. 15(8):409–413.

- Wilson KL, Doswell JT, Fashola OS, Debeatham W, Darko N, Walker TM, Danner OK, Matthews LR, Weaver WL. 2013. Using augmented reality as a clinical support tool to assist combat medics in the treatment of tension pneumothoraces. Mil Med. 178(9):981–985.

- World Health Organization. 2010. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations. Geneva: WHO Press.