Abstract

Curriculum change is relatively frequent in health professional education. Formal, planned curriculum review must be conducted periodically to incorporate new knowledge and skills, changing teaching and learning methods or changing roles and expectations of graduates. Unplanned curriculum evolution arguably happens continually, usually taking the form of “minor” changes that in combination over time may produce a substantially different programme. However, reviewing assessment practices is less likely to be a major consideration during curriculum change, overlooking the potential for unintended consequences for learning. This includes potentially undermining or negating the impact of even well-designed and important curriculum changes. Changes to any component of the curriculum “ecosystem “- graduate outcomes, content, delivery or assessment of learning – should trigger an automatic review of the whole ecosystem to maintain constructive alignment. Consideration of potential impact on assessment is essential to support curriculum change. Powerful contextual drivers of a curriculum include national examinations and programme accreditation, so each assessment programme sits within its own external context. Internal drivers are also important, such as adoption of new learning technologies and learning preferences of students and faculty. Achieving optimal and sustainable outcomes from a curriculum review requires strong governance and support, stakeholder engagement, curriculum and assessment expertise and internal quality assurance processes. This consensus paper provides guidance on managing assessment during curriculum change, building on evidence and the contributions of previous consensus papers.

“For every assessment question there is often more than one answer that could be correct.”

Cees van der Vleuten, personal communication, circa 2000

Introduction

Consider how students discuss their health professional education (HPE) programme – “Our programme is mostly alright but some stuff seems irrelevant to what we have to do.” “Some of the clinical experiences are just watching, not doing, yet we have to get a lot of things signed off by people we hardly see”. “The assessment relies too much on end of year exams, not what we do through the year”. “We do not receive much feedback and most of it is unhelpful“. “The exam questions seem to be just a collection of random questions unrelated to what we do. “Dr X always writes questions about his/her pet interests rather than what is in the curriculum so we have to attend his/her lectures to work out what to study”. “A new curriculum was introduced to make the course more current and interesting but it is safer to focus learning on what is assessed”.

Practice points

Curriculum outcomes, content, delivery and the assessment of learning are closely inter-related within a curriculum “ecosystem”.

Understanding the ecosystem and engaging stakeholders is critical to the success of curriculum or assessment change.

Change in any component of this ecosystem should consider the potential impact on other components as there may be unintended consequences that impede learning.

Assessment practices within a curriculum change must respect and align with internal and external drivers of change.

Assessment may be used as one quality assurance approach, but substantial curriculum changes may require substantial assessment re-design to guide achievement of graduate outcomes.

Adequate and sustainable outcomes on assessment change relies on strong governance and support, stakeholder engagement, expertise and quality assurance processes.

What do such comments mean? Why and by whom are they perceived in that way? What is a “good programme”? Who is the best judge of what is “good” or “bad”?

Health professional education programmes are often complex because they provide more than a university degree. Graduates are expected to be capable of entering the workforce and providing care. Medical students are eligible to commence specialist training. Health care is important to the whole community, so funders, regulators, employers, profession groups, students and the general population are interested in programme design and quality. Central to each programme is the curriculum, defined as “learning opportunities provided by the institution to meet goals established by internal and external bodies” (Merriam-Webster online Dictionary, 2024). These goals are often expressed as graduate outcomes and reflect preparation for future roles. Central to the curriculum is how learning is assessed, because learners focus on curriculum components known to be assessed (Newble and Jaeger Citation1983; Bezuidenhout and Alt Citation2011). Assessment often dominates learner thinking and behaviour. More senior peers are asked for advice, past papers are sought and subscriptions to external examination banks provide practice, suggesting competing undercurrents in assessment that may skew learning towards passing exams rather than achieving graduate outcomes. Managing these undercurrents within a dynamic healthcare system can be difficult, depending on participants, faculty, students and the mix of clinical experiences (Hays et al. Citation2020). Even subtle or minor variations may mean the learning varies within and across learner cohorts and locations, endowing each programme with a “life” of its own. Contexts vary even more across national boundaries, where different cultures and healthcare systems may make apparently identical curricula quite different at delivery.

Previous Ottawa Consensus papers have provided guidance on how to design assessment practices (Norcini et al. 2011; Citation2018; Heenaman et al. 2021; Fuller et al. Citation2022, Boursicot et al. Citation2011), but not in the context of curriculum change. This paper focuses on strategy for why, how and when to apply available assessment design guidance when learning activities change.

We are therefore approaching curriculum design from an assessment perspective, explaining the importance of assessment in supporting changes to learning. We acknowledge that most of this is based on the literature concerning primary medical qualifications rather than other health professions and postgraduate programmes, where there is less documentation. However, while there is unlikely to be a single, correct set of assessments for all contexts, most health professional education (HPE) programmes are likely to reflect similar principles.

Purposeful instructional design

We start by explaining the close relationship between assessment and learning. A health professions education (HPE) programme is much more than a list of what must be learned to complete a course or programme. It is a complex, dynamic entity with three main components: the “content” to be learned, the process of delivering (teaching and learning strategies) and the assessment of learning achievement, all guided by planned graduate outcomes and dependent on substantial healthcare system experience. The content includes the knowledge, skills and behaviours expected of new graduates from the programme, often referred to as the syllabus (Burton and McDonald Citation2001). This content is usually organised within curriculum domains, which are conceptual groupings of related material (Behar and Ornstein Citation1994) that reflect the professional context in which learning is applied and the graduate outcomes to be achieved. Domains usually overlap to a variable extent because they combine components of the curriculum differently, according to graduate outcomes. Achieving graduate outcomes requires satisfactory achievement in all curriculum domains, with all curriculum content and intermediate learning outcomes mapped to graduate outcomes. This is known as constructive alignment (Biggs Citation1996). The focus of assessment should be for, of and as learning (Dann, Citation2014), moving through junior to senior years from “knows how” and “shows how” to “does” and “is” in the revised Miller”s Pyramid and from “remember” to “evaluate” and “create” in the revised Bloom”s Taxonomy (Anderson and Krathwohl Citation2001; Cruess et al. Citation2016). While there are many assessment methods and formats, this progression requires increasing use of workplace-based assessment of how competencies are chosen and applied, the basis of the concept of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) (Norcini and Burch Citation2007; Boursicot et al. Citation2011; ten Cate et al. Citation2015), particularly by graduation and into postgraduate education.

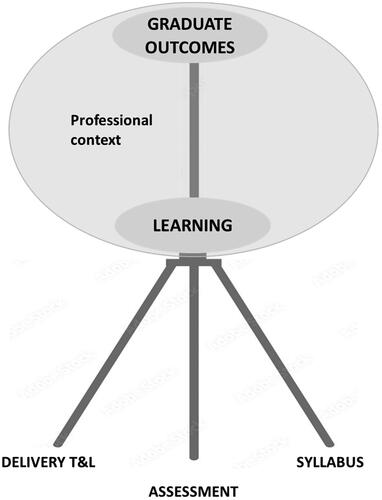

Although often considered independently, including listing as separate standards in most accreditation standards documents, curriculum content, teaching and learning methods and assessment practices are so closely interwoven that they should always be considered together as part of a curriculum ecosystem. Conceptually they form a “tripod” that supports learning the “right things” in the “right way” (Kibbe et al. Citation1994), to which could be added “at the right time” and “for the right purpose”. Change in only one or two legs of the tripod is likely to affect balance. This close relationship is depicted in .

Figure 1. The curriculum ecosystem: content, teaching and learning (T&L), assessment contextualised with health professional roles, the healthcare system and the wider community.

Ideally, all three curriculum components provide learners with consistent messages about what and how to learn. This is the core of constructive alignment (Biggs Citation1996), a concept that may be extended to include a vision or mission for the programme, selecting certain kinds of students and programme evaluation, but those facets are not within the scope of this paper. The importance of constructive alignment is that it should be built into the entire curriculum ecosystem. In this paper the use of the term “curriculum” refers to that ecosystem, although our primary focus is on how learning is assessed.

Change in just one part of the curriculum ecosystem may have unintended consequences for learning. For example, a “hidden” curriculum may develop, where clinical experience, assessment or both drift away from alignment with curriculum content and/or graduate outcomes (Jackson Citation1968). This may have a negative impact on learning, with learners exposed to competing pressures that are difficult to control. The first pressure is workplace culture, which has a significant influence on student learning delivery and outcomes (Lempp et al. Citation2004). Regardless of what curriculum documents state, learning depends to an extent on where, when, how and by whom the curriculum is experienced. The second is how learning is assessed. This may exert more influence on learning than curriculum content or delivery – “assessment drives learning” (Newble and Jaeger Citation1983). Further, learning approaches may be different when scores contribute to progress decisions rather than “just” provide feedback on progress (Rapauch et al. Citation2013). A concrete example of this is the impact of standardised national examinations, which have shown in several contexts to improve factual knowledge more than higher cognitive processes such as understanding and application in practice (Bezuidenhout and Alt Citation2011; Jürges et al. Citation2012). While they may provide confidence that at a single moment in time examination (“SMITHEX”) all candidates meet the same benchmark standard (Dave et al. Citation2020), students may focus on short-term learning to pass assessment that “matters” (e.g. eligibility for a licence) rather than learning for future practice. Learning journeys are longitudinal and incremental; what may be more important is assessing progress and trajectory, which is more like a slope than a series of steps. Assessment should match and facilitate that learning progress. The third is that external pressures from accreditation agencies, employers or funders may request changes to produce “better” graduates and a more inclusive workforce, but responses do not necessarily penetrate to the point of programme delivery. Examples include the increasing emphasis placed on professionalism, work readiness and patient safety, all laudable attributes that are not easy to assess. Further, there is some evidence that clinical assessors of students close to graduation may focus on system factors, such as teamwork, safety and trustworthiness, rather than traditional individual clinical competencies (Malau-Aduli et al. Citation2021).

Health professional education programmes should not be static. Scientific development improves continuously and clinical practice evolves in response to new content, new learning experiences and new roles. Future community needs and professional roles must be considered, more likely reflecting the perspectives of funders, regulators and employers. Advances in technology improve access to learning resources, current clinical information andnew assessmentformats, but should be tools rather than main drivers of development. The “shelf life” of a curriculum is difficult to measure but all health professions curricula should be regarded as “living” documents that require regular review to maintain currency. All changes should be evidence-based, described clearly and evaluated. This is “healthy” curriculum development.

Not all curriculum changes are necessarily “healthy”, particularly if implemented on the run. Changes in teaching faculty may bring different perspectives to existing content, new ideas and energy, but sometimes directed towards personal interests rather than proven needs. Learners may request additional lectures on more complex topics, but perhaps learning resources should be reviewed rather than increasing didactic activities. A “new” assessment method or format may gain popularity and be introduced without empirical evidence or consideration of the broader curriculum ecosystem and potential unintended consequences. For example, even minor changes can result in “curriculum creep”. All curriculum changes should be developed appropriately and implemented uniformly across the programme. More substantial change may be sparked by new leadership that wants to motivate/bring together faculty around an important project, an accreditation report that recommends or requires curriculum reform, or a major change in circumstances that affects curriculum delivery. Examples of major changes include the recent COVID-19 pandemic, international conflicts and large natural disasters that disrupt “normal” healthcare and HPE delivery. These reasons are not mutually exclusive and may relate to both internal and external pressures. External pressures may be regarded as more urgent due to reputational risk.

An explanation commonly used for not changing assessment during curriculum change is that assessment can be used as quality assurance by showing that a curriculum change does not disadvantage learners. Many curriculum delivery initiatives, such as Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (LICs) have taken this approach (Worley et al. Citation2001; El et al. Citation2019). While this assertion has some strengths in support of innovation, substantial curriculum changes may require substantial assessment re-design to guide learning.

In this paper we use scenarios that are based on real although de-identified examples (see ) to demonstrate how the principles may be applied in a variety of contexts (). These principles are based on both the literature, which is skewed heavily towards primary medical education and the pooled experiences of the authors, which although broader is still medicine focused. Primary HPE qualification programmes tend to have more stringent external accreditation standards and processes, while postgraduate programmes tend to be more in the hands of the individual professions, producing greater variation both nationally and globally in curriculum and assessment approaches. Despite these limitations, we believe that the principles may be valid at all levels of education for all health professions and have included scenarios reflecting both specialty and continuing professional development contexts.

Table 1. Scenarios for consideration of assessment change.

Table 2. Application of principles demonstrated by scenarios.

Principles to guide successful and sustainable assessment change during curriculum review

Leadership, governance and ownership

Clear governance structures and delegations are required to guide any curriculum review process from preparation through to completion. Change management is not covered in detail here but success requires leadership, engagement, organizational “readiness”, clear outcomes, clear decision-making and data collection to provide provenance of change and its evaluation (Gelaidan et al. 2017; Ford et al. Citation2021; Law Citation2022). Leaders should be independent of “vested” interests and focus on aspirations to improve healthcare outcomes and meet accreditation requirements as conduits for activity that unite teams. Clear, accepted, unequivocal procedures facilitate decisions that are more likely to be implemented. Respectful disagreement should be encouraged to refine ideas and strategies. Are decisions made by consensus or majority vote? If so, do all participants have voting rights? How do options fit with institutional regulations, professional norms and community expectations? Data collection to track changes and document reasons for change is essential to demonstrate curriculum provenance and evaluation of the impact of changes, particularly for innovative changes. In major reviews there is potential for distraction and disaffection, with students from the “old” course feeling neglected or disadvantaged. It may be wise to have two separate curriculum and assessment teams – one each for the “old” and “new” programmes to improve messaging clarity.

From an assessment perspective, a key issue is the appointment of a senior faculty member with, or with access to, assessment expertise to monitor the potential impact of any curriculum change on assessment practices. While there may not be a single answer to every assessment question, the focus should be on finding “better” ways to guide learning and measure achievement. Approaching curriculum or assessment change should consider what we call the 6 Ps, listed in .

Table 3. The 6 Ps of engagement in curriculum and assessment review.

Curriculum governance structures should include faculty members, senior students, recent graduates, employers of graduates and patient representatives to oversee processes and to provide opportunities for contribution. Considerable energy and effort are required to provide a “return on investment” for all stakeholders. Debate, sometimes robust, is normal, particularly early in the process as differing perspectives are voiced and mutual understanding is achieved. Respectful discussions in a contest of ideas should not hinder the prospects of participants. New ideas should be encouraged. Bringing in an external consultant with awareness of developments in other medical programmes may increase awareness of current trends. “Looking outside” may be useful learning: consider sending review team members to visit other programmes that are well regarded. Regular progress reports, particularly to students and faculty, should maintain engagement and encourage feedback. Consensus should be the goal but is not mandatory, so long as all work towards implementation. These steps should improve the acceptability, achievability and quality of changes.

The role of faculty is much broader than providing information to learners (Harden and Lilley. Citation2018) They possess the content, context, delivery and assessment expertise that provides the programme. Their engagement is critical to successful change (Cintra et al Citation2023). They need to engage in any review discussions and, ideally take some ownership of outcomes. However, they are busy people and continuing quality improvement (CQI) is usually not explicit in position descriptions. Participating faculty will need dedicated time to commit to the task. Additional faculty may be required to ease the workload of existing faculty. This may be an ideal time for faculty development activities that expand educational expertise and enhance career prospects.

The role of learners is much broader than receiving information (Karakitsiou et al. Citation2012). They are both the initial “consumers” of HPE programmes and the future clinical and educational workforce. Students can provide valuable perspectives and so should join review teams. Their participation may ensure that any new assessment strategy encourages learning towards achieving graduate outcomes, reducing resistance and facilitating implementation and sustainability. For a major review recruiting one or more students to the project team (e.g. as an intercalated HPE project) may add value to both the programme change and the student(s) future career.

Purpose

There are three levels of purpose. The purpose of the overall programme is unlikely to change, focusing on providing an appropriate healthcare workforce as defined by the regulator. Where changes are proposed for curriculum and/or assessment, the purpose of each change should be clear. Where changes potentially require different assessment methods, the purpose of each method should be clear. Curriculum change is an opportunity to re-visit the overall assessment philosophy and the purpose of the assessment, building on empirical evidence and reflecting contemporary trends to improve HPE programmes. Is the primary goal to guide learning, to demonstrate particular workforce outcomes or to achieve national accreditation status? All are important yet may require different applications of similar resources. Whether it is addition of contemporary content or an amendment to graduate outcomes, the whole curriculum ecosystem may be affected. Clarity and shared understanding of goals and objectives of the change are required to facilitate moving beyond the “what” and “why” to “how”. Is this “routine maintenance”, where a focused change is required in response to a specific trigger? Is it a major overhaul, such as introduction of a parallel curriculum (different sites or placement models) with identical graduate outcomes? Is the change effectively a new programme, such as changing from lower to higher integration (or vice versa). The more substantial the review, the more resources, educational expertise and faculty-wide engagement are necessary. Where possible, adding new content should be resisted due to the risk of curriculum or assessment overload. Replacing less important or older content is preferable.

Constructive alignment

Constructive alignment is central to purposeful design and any curriculum review should aim to correct or improve the consistency, balance and alignment of programme components to support and strengthen learning. Even “minor”, apparently “isolated” changes that address specific issues may impact other programme components. In particular, any changes to curriculum outcomes and delivery are likely to require revision of the assessment strategy. More substantial changes may require a programme-wide review of all curriculum components. For example, changing from lower to higher curriculum integration requires a matching change in assessment across the curriculum. Further, a review of any part of an assessment schedule requires a review of the whole schedule to maintain alignment and balance. The assessment blueprint and sampling should be based on the curriculum blueprint to demonstrate constructive alignment (Raymond and Grande 2018).

Systematic and comprehensive

Every aspect of the curriculum, across all domains, should be considered as eligible for assessment, guided by the graduate outcomes (Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten Citation2004). This includes a wide range of cognitive, procedural and behavioural attributes. Assessment should go beyond relying on the “easier to measure” attributes, such as knowledge and simulated skills, to incorporate other important attributes, such as elements of professionalism and self-care. The current approach is to conduct more frequent assessment throughout programmes with multiple assessors, methods and contexts to “shine a light” on learning progress across the whole curriculum (Norcini et al. Citation2018). A more elaborate model is programmatic assessment, which includes consideration of the whole curriculum nexus to focus on learning (van der Vleuten et al. Citation2012; Heeneman et al. Citation2021; Torre et al. Citation2021). Just as delivering a curriculum is feasible for only a sample of the “universe” of requirements for early clinical practice, assessment is feasible for only a sample of the curriculum, based on a programme-wide assessment blueprint. Appropriate sampling strengthens validity and sends messages to learners and teachers that the whole curriculum is important. Learning portfolios are a suitable place to gather complementary information that builds a “profile” of graduates, although much depends on what is included and how it is evidenced. The role of learning portfolios in decision-making continues to be a work in progress (Buckley et al. Citation2009; Hong et al. Citation2021; Tan et al. Citation2022).

Selection of individual assessment methods

A wide range of assessment methods and formats is available. As with assessment development in general, the choice of individual methods should be based on the purpose. Content, delivery methods and context of the changing curriculum. A convenient model to consider is the assessment utility of individual methods (Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten Citation2004). While the traditional focus may be on methods with higher reliability, those with higher validity and educational impact are important for “harder to assess” attributes and outcomes such as professionalism, patient safety and self-care. A “composite reliability” approach should be adopted to ensure that learning progress is achieved across all Domains (Moonen-van Loon et al. Citation2013).

Adopting a new assessment method should be part of a purposeful design. Care should be taken not to simply increase the assessment workload although if this includes previously non-assessed components some flexibility may be required. Assessment methods should be replaced on a “like for like” basis to reduce unintentional duplication or narrowing of overall assessment. For example, a clinical assessment method should be replaced by another. If workplace based assessment (WBA) are added to objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE) it may be advisable to decrease the number of OSCEs and sample items for both from the same blueprint, focusing on methods, individual item quality and assessor training. Further, some assessment changes may require substantial re-design. For example, moving from competencies to EPAs, a contextualized “meta-competency” that is linked to workplace roles and tasks, may require much broader, multi-method assessment over an appropriate time period (ten Cate et al. Citation2015).

Clarity is required about how each assessment contributes to achieving graduate outcomes. Curriculum change is an opportunity to increase the quality and quantity of feedback provided; the lack of this is a common student complaint (Lefroy et al. Citation2015), whether the primary driver is “for”, “of” or “as” learning. Students may behave differently for each of these purposes. All assessment can be “for” learning and so central to career development. Progress decisions should consider a wide range of different assessments with different methods and assessors. Consider making some assessments “hurdles” during learning rather than graded assessments at the end of the stage or year. This spreads the assessment workload and ensures that important but “harder to assess” attributes are included.

Other options for change should be explored as there may be more than one approach to addressing identified issues. For example, increasing the number and the quality of assessment items, adding clinical scenarios to written items, increasing the number of clinical assessors and improving assessor training in current methods may improve assessment utility more than changing methods (Schuwirth and Van Der Vleuten Citation2004; van der Vleuten and Schuwirth Citation2005). The role of technology in assessment ideally should be driven by educational needs. Technology advances rapidly and provides useful assessment tools and management software. However, technology should be an enabler, should not dictate assessment design principles and requires contingency planning as outages occur occasionally (Sen Gupta et al. Citation2021)

The importance of individual learning styles is controversial, but learners may adapt their learning approaches in response to assessment practices (Newble and JaegerCitation1983; Wilkinson et al. Citation2007). For example, a decision to increase the number of MCQ assessments for clinical rotations may encourage rote learning from textbooks rather than taking opportunities to engage in clinical practice. There may be some generational influences with students and faculty usually a generation apart, so there may be differences in preferences and understanding (Reyes et al. Citation2020). Given the diversity of students joining health professions education, consideration should be given to the potential for selected assessment tools unfairly disadvantage particular groups of students (de Lisa and Lindenthal Citation2012; Tai et al. Citation2023). Current medical school entrants may be more interested in “co-creation” of curriculum content, delivery and assessment (Plochoki 2019; Twenge Citation2009). This interest and energy, if captured, may be an asset for change processes.

Agreed national standards and graduate outcomes should guide the scope of assessment

Curriculum changes should adhere to clearly defined national standards for the relevant jurisdiction and profession. For medicine, these are focused on graduate outcomes, usually based on input from regulators, funders, the profession and the broader community, although overseen by the regulator. Programmes may have additional graduate outcomes for their local context, branding purposes, such as research proficiency, work-readiness or scope of practice. These outcomes should be assessed but not at the expense of the national graduate outcomes. Future-orientation may be important and should be considered, e.g. impact of climate change, planetary health and evolving roles of graduates. Students are interested in these topics and may contribute strongly to discussions if invited, but they are difficult to assess. Another area where the assessment programme can “drift” away from the revised curriculum relates to learning outcomes for each year/phase/stage. These should be calibrated carefully and mapped to graduate outcomes, particularly if they represent progression decision points. This contributes to the consistency of assessment practices throughout the whole programme. Formal standard setting methods should be applied as appropriate to each assessment method (Norcini, 2005). Although imperfect, these methods may improve the precision of assessments, usually combining pre-hoc consensus judgments with post-hoc psychometrics, resulting in fairer decisions, particularly if stronger psychometric measures are adopted, such as Item Response Theory (IRT) (Schauber and Hecht Citation2020).

Progress decision-making processes should be evidence-based, clear and consistent

The management of candidates at the borderline between “safe” and “unsafe” to proceed is becoming increasingly important and yet may be highly sensitive to curriculum and assessment change. Two complementary issues must be considered when decision-making assessment data are changed – can the borderline be defined more precisely and can we improve how to manage candidates at, near or below borderline scores?

There are many sources of potential error in any score and this matters more at the borderline where decisions are made about learning progress. The goal of assessment is to identify and manage those sources of error so that candidate scores are true measures of ability with as few false positives and negatives as possible. Minimization of error may be summarized as “reducing the grey zone” between a clear pass and a clear fail (Schauber and Hecht Citation2020). The traditional approach is to award a pass if combining scores across methods reaches a defined numerical score, either criterion or norm-referenced, with some measure of precision expressed as either p-values or confidence intervals. In HPE the context is more complex than in most higher education degree programmes because many methods and assessors are used and assessment data include both quantitative and qualitative information which cannot be combined to produce a single numerical score. Further, the stakes in HPE are higher for candidates (careers), patients (safety) and employers (quality of care), so minimizing error and improving precision are paramount. There is increasing emphasis on assessment item quality, blueprinting, sampling and standard setting. Combining numerical scores should adhere to classical measurement theory – ideally all scores are “interval” measurements (Foulkes et al. Citation1994). Including qualitative information, including narrative and reflective components is essential but makes more complex the task of reaching an overall progress decision (Charon Citation2001; Wald et al. Citation2012). Ideally, all information is considered, based on consensus judgements by experienced assessors, with discrepancies discussed by a panel. Any weighting of methods or items should reflect what is necessary to make diagnoses or guide management, guided by graduate outcomes. Clarity is required for how all assessment data are managed. The use of the Standard Error of Measurement may improve predictability of borderline scores (Hays et al. Citation2008). Rules of progression should be consistent with overall university regulations to reduce successful appeals (Hays et al. Citation2015). Decision-making processes should be available to all staff and students. Even relatively minor curriculum or assessment changes can inadvertently alter decision-making algorithms, potentially reducing alignment and producing leniency for weaker candidates.

The second issue concerns managing candidates with borderline scores. Most HPE learners are academically strong and commence learning in highly competitive HPE programmes with an expectation that they will succeed. This places greater responsibility on learning institutions to identify learners not progressing as expected and offer them increased learning support. Evidence is mounting that borderline candidates are more likely to fail future assessments and are often identified early in HPE programmes (Cleland et al. Citation2008). Providing increased learning and pastoral support is now an expectation. In HPE poor academic progress is usually related to non-academic pressures that may be amenable to intervention (Hays et al. Citation2011). Increasing access is a current “hot topic” for students previously excluded from entry due to rigid selection and workplace ability factors. There is pressure to adopt “universal design for learning” (UDL) approaches that were originally developed for special education. The laudable aim is to improve inclusivity by increasing flexibility in teaching and assessment methods (Rao et al. Citation2014), but its application in HPE higher education remains uncertain.

Quality assurance

Two quality assurance processes are available to ensure that medical programmes meet the standards laid down for both higher education and the broader community that graduates will serve. Most HPE programmes are delivered within accredited higher education institutions (usually universities) which must maintain the quality of all education programmes through internal quality assurance processes overseen by senior faculty. The second quality assurance process, common to most professional programmes, is external to the university, managed by health professional regulation agencies and including broader professional, regulatory, employer and funder perspectives on contemporary roles of graduates. Both processes involve periodic reviews by a panel selected carefully to represent stakeholders and provide relevant expertise.

Internal QA

Internal QA is under the control of the relevant institution. The review panel includes representatives from other education programmes within the university and some external representatives of similar programmes in other universities, the relevant health profession and local healthcare providers and employers. The primary focus is scrutiny of policies, systems and procedures, showcasing best practices, identification of areas for improvement, and dissemination of lessons learned. This is achieved mostly by desk audit of documentation, with some interviews with faculty and students. Assessment is part of that focus, but there are often substantial differences between health professional and other programmes with respect to methods, standard setting and rules of progression. Internal processes must take account of external accreditation requirements, particularly those relating to future healthcare and community roles of graduates but focus on more generic higher education standards of curriculum design. Internal QA reviews are usually less intensive than external accreditation processes. Reports should be submitted as an appendix to support external accreditation review submissions, as this provides evidence of compliance with higher education standards, allowing accreditation processes to focus on compliance with HPE standards. An understated but substantial benefit of dual internal and external QA processes is that they inform each other. Further, the self-reflection component of external QA may encourage stronger internal QA.

Internal QA for postgraduate educational programmes is similar in principle although different in context. These programmes are often not delivered by universities so “institution” merges with “profession”. These are smaller entities which may not have the resources for comprehensive educational expertise, although the need for internal QA is perhaps even higher than for university-delivered programmes. The same principles should be applied.

External QA (accreditation)

Accreditation processes are under the control of the regulator for the relevant jurisdiction. The panels comprise entirely external members from other HPE programmes, the regulator and trained representatives of the community, the wider profession and recent graduates. The primary focus is on meeting defined national standards that include issues such as governance, sustainability of resources and engagement with the health care system. Curriculum, teaching and learning and assessment standards are explored carefully from the perspective of how well graduates achieve graduate outcomes and are ready to enter the profession. Assessment practices differ from those of the wider higher education sector; this may be an area of overlap and a degree of tension between universities and regulators. Accreditation standards for assessment are intentionally broad, encouraging providers to innovate so long as graduate outcomes are achieved and evidence-based current assessment developments are reflected. Current emphases include authenticity, WBA, applied knowledge, professionalism, and assessment for learning with regular, constructive and meaningful feedback. Constructive alignment must be demonstrated in curriculum and assessment mapping.

While the expression of medical education and assessment may vary between institutions within accreditation jurisdictions, variations may be greater across national boundaries, particularly amidst the resourcing realities in “global south” countries where accreditation processes may differ from those in “global south” countries (Nadarajah et al. Citation2023). Institutions may have greater autonomy and may choose to produce either a workforce to address local needs or graduates that will migrate to more attractive or safer countries. This does not mean that less resourced nations necessarily have lower quality programmes, as there are many examples of locally developed innovative and effective programmes (Antunes dos Santos and Nunes Citation2019). “Transplanting” programmes from well to less resourced nations does not necessarily ensure quality as curriculum delivery relies on the local healthcare system, which may be quite different to that of the “parent” programme. Even though most of the global health professional workforce is trained in global south countries, less is known about this diversity in those contexts because fewer than 20% of the publications in medical education come from those countries (Wondimagegn et al. 2021; Amaral and Norcini. 2019).

Conclusion

Curriculum review is relatively frequent, whether unplanned or planned, to manage the emergence of new knowledge and skills, developments in teaching and learning methods or new roles in the healthcare system. Changes may be driven by either internal (faculty or students) or external (employer or regulator) pressures. Reviewing assessment practices may be overlooked by debate on content or delivery, not recognising the centrality of assessment in guiding learning. There is potential for weakening constructive alignment and producing unintended consequences for learning, undermining or negating the impact of important, even well-designed curriculum changes. Changes to any component of the curriculum ecosystem - graduate outcomes, content, instructional design or assessment – should trigger an automatic review of the whole nexus to maintain constructive alignment. Powerful external drivers of curriculum change include national examinations, programme accreditation and healthcare system expectations. Internal drivers are also important, such as adoption of new learning technologies and learning preferences of students and faculty. Each assessment programme sits within its own context which may influence the outcomes of curriculum and assessment review. Achieving optimal and sustainable outcomes requires strong governance and support, stakeholder engagement, curriculum and assessment expertise and internal quality assurance processes. This consensus paper provides guidance on managing assessment during curriculum change.

Glossary

Curriculum ecosystem: Describes the complex inter-relationship of learning content, delivery and assessment that exists in the dynamic context of both higher education and healthcare systems.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no declarations of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard B. Hays

The authors are an international group recruited through AMEE networks to provide expertise, contribution from educators and learners, and representation of geographic and health systems diversity.

Richard B Hays, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia.

Tim Wilkinson

Tim Wilkinson, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Lionel Green-Thompson

Lionel Green-Thompson, University of Capetown, South Africa.

Peter McCrorie

Peter McCrorie, University of Cyprus, Larnaca, Cyprus.

Valdes Bollela

Valdes Bollela, Universidade Cidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Vishna Devi Nadarajah

Vishna Devi Nadarajah, Newcastle University, Johor, Malaysia.

M. Brownell Anderson

M. Brownell Anderson, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal.

John Norcini

John Norcini, FAIMER, Philadelphia, USA.

Dujeepa D. Samarasekera

Dujeepa D. Samarasekera, University of Singapore, Singapore.

Katharine Boursicot

Katharine Boursicot, Health Professional Assessment Consultancy, Singapore.

Bunmi S Malau-Aduli

Bunmi S Malau-Aduli, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia.

Madalina Elena Mandache

Madalina Elena Mandache, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova, Romania.

Azhar Adam Nadkar

Azhar Adam Nadkar, Stellenbosch University, Capetown, South Africa.

References

- Amaral E, Norcini J. 2023. Quality assurance in health professions education: role of accreditation and licensure. Med Educ. 57(1):40–48. Epub 2022 Jul 29. PMID: 35851495. doi:10.1111/medu.14880.

- Anderson LW, Krathwohl D. 2001. A revision of bloom”s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: longman. Theory into Practice. 41(4):212–218. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2.

- Antunes dos Santos R, Nunes MdPT 2019. Medical education in Brazil. Med Teach. 41(10):1106–1111. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1636955.

- Behar LS, Ornstein A. 1994. Domains of curriculum knowledge: an empirical analysis. The High School J. 77(4):322–329. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40364756. Accessed 19 Sept. 2023.

- Bezuidenhout MJ, Alt H. 2011 “Assessment drives learning”: do assessments promote high-level cognitive processing? Published Online:1 Jan 2011. [Accessed 10 April 2024]. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC37738.

- Biggs J. 1996. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ. 32(3):347–364. doi:10.1007/BF00138871.

- Boursicot K, Etheridge L, Setna Z, Sturrock A, Ker J, Smee S, Sambandam E. 2011. Performance in assessment: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa conference. Med Teach. 33(5):370–383. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.565831.

- Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, Khan KS, Zamora J, Malick S, Morley D, Pollard D, Ashcroft T, Popovic C, et al. 2009. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach. 31(4):282–298. doi:10.1080/01421590902889897.

- Burton JL, McDonald S. 2001. Curriculum or syllabus: which are we reforming? Med Teach. 23(2):187–191. doi:10.1080/01421590020031110.

- Charon R. 2001. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897.

- Cintra KA, Borges MC, Panúncio-Pinto MP, de Almeida Troncon LE, Bollela VR. 2023. The impact and the challenges of implementing a faculty development program on health professions education in a Brazilian Medical School: a case study with mixed methods. BMC Med Educ. 23(1):784. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04754-8.

- Cleland JA, Milne A, Sinclair H, Lee AJ. 2008. Cohort study on predicting grades: is performance on early MBChB assessments predictive of later undergraduate grades? Med Educ. 42(7):676–683. Available doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03037.x.

- Cruess L, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. 2016. Amending Miller”s pyramid to include professional identity. Acad Med. 91(2):180–185. Available doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913.

- Dann R. 2014. Assessment as learning: blurring the boundaries of assessment and learning for theory, policy and practice. Assess Educ. 21(2):149–166. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2014.898128.

- Dave S, Chakravorty I, Menon G, Sidhu K, Bamrah J, Mehta R. 2020. Differential attainment in summative assessments within postgraduate medical education & training: 2020 thematic series on tackling differential attainment in healthcare professions. Sushruta J Health Policy Opinion.. 13(3) doi:10.38192/13.3.15.

- de Lisa JA, Lindenthal JJ. 2012. Reflections on diversity and inclusion in medical education. Acad Med. 87(11):1461–1463. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826b048c.

- El BM, Anderson K, Finn GM. 2019. A narrative literature review considering the development and implementation of longitudinal integrated clerkships, including a practical guide for application. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 6:238212051984940.

- Ford J, Ford L, Polin B. 2021. Leadership in the implementation of change: functions, sources, and requisite variety. Journal Change Manag. 21(1):87–119. [Accessed 27 February 2024 Available: 10.38192/13.3.15. doi:10.1080/14697017.2021.186169713(3):1–7.

- Foulkes J, Bandaranayake R, Hays R, Phillips G, Rothman A, Southgate L. 1994. The Certification and Recertification of Doctors: Issues in the Assessment of Clinical Competence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fuller R, Goddard VCT, Nadarajah VD, Treasure-Jones T, Yeates P, Scott K, Webb A, Valter K, Pyorala E. 2022. Technology enhanced assessment: ottawa consensus statement and recommendations. Med Teach. 44(8):836–850. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2022.2083489.

- Gelaidan HM, Al-Swidi A, Mabkhot HA. 2017. Leadership Behaviour for Successful Change Management. 2017. In: Farazmand A, Editors. Global Encyclopaedia of Public Administration, Public Policy and Governance. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3138-1. Accessed 27 February 2024

- Harden RM, Lilley P. 2018. The eight roles of the medical teacher: the purpose and function of a teacher in the healthcare professions. London: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Hays RB, Hamlin G, Crane L. 2015. 12 tips: increasing the defensibility of assessment. Med Teach. 37(5):433–436. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.943711.

- Hays RB, Lawson M, Gray C. 2011. Problems presented by medical students seeking support: a possible intervention framework. Med Teach. 33(2):161–164. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.509415.

- Hays RB, Ramani S, Hassell A. 2020. Healthcare systems and the sciences of health professional education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 25(5):1149–1162. doi:10.1007/s10459-020-10010-1.

- Hays RB, Sen Gupta TK, Veitch J. 2008. The practical value of the standard error of measurement in borderline pass/fail decisions. Med Educ. 42(8):810–815. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03103.x.

- Heeneman S, de Jong LH, Dawson LJ, Wilkinson TJ, Ryan A, Tait GR, Rice N, Torre D, Freeman A, van der Vleuten CPM. 2021. Ottawa 2020 consensus statement for programmatic assessment – 1. Agreement on the principles. Med Teach. 43(10):1139–1148. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1957088.

- Hong DZ, Lim AJS, Tan R, Ong YT, Pisupati A, Chong EJX, Quek CWN, Lim JY, Ting JJQ, Chiam M, et al. 2021. A systematic scoping review on portfolios of medical educators. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 8:23821205211000356. doi:10.1177/23821205211000356.

- Jackson P. 1968. . Life in classrooms. Retrieved November 2005 from: http://www.kdpoorg/images/Jackson.jprg.

- Jürges H, Schneider K, Senkbeil M, Carstensen CH. 2012. Assessment drives learning: the effect of central exit exams on curricular knowledge and mathematical literacy. Econ Educ Rev. 31(1):56–65. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.08.007.

- Karakitsiou DE, Markou A, Kyriakou P, Pieri M, Abuaita M, Bourousis E, Hido T, Tsatsaragkou A, Boukali A, de Burbure C, et al. 2012. The good student is more than a listener – The 12 + 1 roles of the medical student. [Accessed 10th April 2024]. Med Teach. 34(1):e1–e8. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.638006.

- Kibbe DC, Kaluzny AD, McLaughlin CP. 1994. Integrating guidelines with continuous quality improvement: doing the right thing the right way to achieve the right goals. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 20(4):181–191. Available doi:10.1016/S1070-3241(16)30060-8.

- Law MY. 2022. A review of curriculum change and innovation for higher education. JETS. 10(2):16–23. doi:10.11114/jets.v10i2.5448.

- Lefroy J, Watling C, Teunissen PW, Brand P. 2015. Guidelines: the do”s, don”ts and don”t knows of feedback for clinical education. Perspect Med Educ. 4(6):284–299. doi:10.1007/s40037-015-0231-7.

- Lempp H, Seal C, Jackson PW. 2004. The hidden curriculumin undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students” perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 329(7469):770–773. PMID: 15459051; PMCID: PMC520997. [Accessed 10th April 2024] doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770.

- Malau-Aduli BS, Hays RB, D”Souza K, Smith AM, Jones K, Turner R, Shires L, Smith J, Saad S, Richmond C, et al. 2021. Examiners” decision-making processes in observation-based clinical examinations. Med Educ. ; 55(3):344–353. doi:10.1111/medu.14357.

- Meriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2024. Available: merriam-webster.com Accessed 27 February.

- Moonen-van Loon JMW, Overeem K, Donkers HHLM, van der Vleuten CPM, Driessen EW. 2013. Composite reliability of a workplace-based assessment toolbox for postgraduate medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 18(5):1087–1102. doi:10.1007/s10459-013-9450-z.

- Nadarajah VD, Ramani S, Findyartini A, Sathivelu S, Nadkar AA. 2023. Inclusion in global health professions education communities through many lenses. Med Teach. 45(8):799–801. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2186206.

- Newble DI, Jaeger K. 1983. The effect of assessments and examinations on the learning of medical students. Med Educ. 17(3):165–171. Accessed 27 February 2024. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb00657.x.

- Norcini J, Anderson B, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa MJ, Duvivier R, Galbraith R, Hays R, Kent A, Perrott V, et al. 2011. Criteria for good assessment: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Med Teach. 33(3):206–214. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.551559.21345060

- Norcini JJ. 2003. Setting standards on educational tests. Med Educ. 37(5):464–469. Available doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01495.x.

- Norcini J, Anderson MB, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa MJ, Duvivier R, Hays R, Palacios Mackay MF, Roberts T, Swanson D. 2018. Consensus Framework for Good Assessment. Med Teach. 40(11):1102–1109. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016.

- Norcini J, Burch V. 2007. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 29(9):855–871. PMID: 18158655. doi:10.1080/01421590701775453.

- Plochocki JH. 2019. Several ways generation Z may shape the medical school landscape. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 6:2382120519884325. PMID: 31701014; PMCID: PMC6823979. [Accessed 10th April 2024]. doi:10.1177/2382120519884325.

- Rao K, Ok MW, Bryant BR. 2014. A review of research on universal design educational models. Remedial Spec Educ. 35(3):153–166. doi:10.1177/0741932513518980.

- Raupach T, Brown J, Anders S, Hasenfuss G, Harendza S. 2013. Summative assessments are more powerful drivers of student learning than resource intensive teaching formats. BMC Med. 11(1):61. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-61.

- Raymond MR, Grande JP. 2019. A practical guide to test blueprinting. Med Teach. 41(8):854–861. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1595556.

- Reyes A, Galvan R, Jr, Navarro A, Velasquez M, Soriano DR, Cabuso AL, David JR, Lacson ML, Manansala NT, Tiongco RE. 2020. Across generations: defining pedagogical characteristics of generation X, Y, and Z allied health teachers using Q-methodology. Med Sci Educ. 30(4):1541–1549. PMID: 34457822; PMCID: PMC8368375. doi:10.1007/s40670-020-01043-7.

- Schauber SK, Hecht M. 2020. How sure can we be that a student really failed? On the measurement precision of individual pass-fail decisions from the perspective of Item Response Theory. Med Teach. 42(12):1374–1384. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1811844.

- Schuwirth LWT, Van Der Vleuten CPM. 2004. Different written assessment methods: what can be said about their strengths and weaknesses? Med Educ. 38(9):974–979. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01916.

- Schuwirth LWT, Van der Vleuten CPM. 2011. Programmatic assessment: from assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Med Teach. 33(6):478–485. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.565828.

- Sen Gupta T, Wong E, Doshi D, Hays R. 2021. Stability” of assessment: extending the utility equation [version. 1] MedEdPublish. 10:155. doi:10.15694/mep.2021.000155.1.

- Tai J, Ajjawi R, Bearman M, Boud D, Dawson P, Jorre de St Jorre T. 2023. Assessment for inclusion: rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Educ Res Dev. 42(2):483–497. doi:10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451.

- Tan R, Qi Ting JJ, Zhihao Hong D, Sing Lim AJ, Ong YT, Pisupati A, Xin Chong EJ, Chiam M, Inn Lee AS, Shuen Tan LH, et al. 2022. Medical student portfolios: a systematic scoping review. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 9:23821205221076022. Accessed 10th April 2024 doi:10.1177/23821205221076022.

- ten Cate O, Chen HC, Hoff RG, Peters H, Bok H, van der Schaaf M. 2015. Curriculum development for the workplace using Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs): AMEE Guide No. 99. Med Teach. 37(11):983–1002. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1060308.

- Torre D, Rice NE, Ryan A, Bok H, Dawson LJ, Bierer B, Wilkinson TJ, Tait GR, Laughlin T, Veerapen K, et al. 2021. Ottawa 2020 consensus statements for programmatic assessment – 2. Implementation and practice. Med Teach. 43(10):1149–1160. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1956681.

- Twenge JM. 2009. Generational changes and their impact in the classroom: teaching generation Me. Med Educ. 43(5):398–405. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03310.x.

- Van Der Vleuten CP, M. 1996. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1(1):41–67. doi:10.1007/BF00596229.

- van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth WT. 2005. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Med Educ. 39(3):309–317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02094.x.

- van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessen EW, Dijkstra J, Tigelaar D, Baartman LKJ, van Tartwijk J. 2012. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 34(3):205–214. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239.

- Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. 2012. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 87(1):41–50. Erratum in: Acad Med. 2012 Mar;87(3):355. PMID: 22104060. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa.

- Wilkinson TJ, Wells JE, Bushnell JA. 2007. What is the educational impact of standards-based assessment in a medical degree? Med Educ. 41(6):565–572. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02766.x.

- Wondimagegn D, Whitehead CR, Cartmill C, Rodrigues E, Correia A, Salessi Lins T, Costa MJ. 2023. Faster, higher, stronger - together? A bibliometric analysis of author distribution in top medical education journals. [BMJ Glob Health. 8(6):e011656. PMID: 37321659; PMCID: PMC10367082. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011656.

- Worley P, Couper I, Strasser R, Graves L, Cummings B-A, Woodman R, Stagg P, Hirsh D., 2016. A typology of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 50(9):922–932. doi:10.1111/medu.13084.

- Worley P, Silagy C, Prideaux D, Newble D, Jones A. 2001. The parallel rural community curriculum: an integrated clinical curriculum based in rural general practice. Med Educ. 34(7):558–565. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00668.x.