Abstract

This paper aims to determine the effect of parental education, as an important measure of social origin, on the expectations of 15 year olds to complete higher education in the Netherlands. More importantly, the paper tests specific explanations for this effect. For the empirical analysis, Dutch data from the PISA 2018 survey were used. The results revealed that there is a considerable impact of parental education on the likelihood of expecting to complete higher education in the Netherlands. To a large extent, this social origin effect refers to secondary effects of stratification: students with the same school performance have different expectations regarding higher education that are strongly correlated with their social origin. Parental resources explain only a small part of the direct social origin effect net of school performance. The secondary effects remain largely unexplained after taking parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources into account, suggesting that relative risk aversion drives social differentials in educational expectations.

Introduction

Several studies of social stratification and mobility have established major inequalities by social origin in the development of educational expectations among pupils and students (see, for instance, Buchmann and Park Citation2009; Li and Xie Citation2020; Valdés Citation2022). Educational expectations are important to investigate, not only since expectations are powerful signals of what young people hope to achieve, but also because they have strong implications for their subsequent career development and choices (Madden, Ellen, and Ajzen Citation1992; see also Parker et al. Citation2016). In other words, varying educational expectations by social origin will in the end lead to social inequalities in realized educational attainment and occupational achievement (Sewell, Haller, and Portes Citation1969; Gottfredson Citation1981; Beal and Crockett Citation2010).

The aim of this paper is to determine the effect of parental education, as an important if not the most important measure of social origin, on young people’s expectations to complete a degree in higher education in the Netherlands. Moreover, the paper contributes to the understanding of inequality in these expectations by testing specific explanations for this social origin effect. A first mechanism that mediates the effect of social origin is related to scholarly ability. It refers to the variation in school performance that is associated with family background; in the literature often expressed as primary effects of social stratification (Boudon Citation1974). Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds perform less well in school and, therefore, have lower educational expectations than their higher socioeconomic status peers (Zimmermann Citation2019). A second mechanism that explains individual differences in the expectation to complete a degree in higher education has to do with the direct effect of social origin that is independent of school performance; referred to as secondary effects of social stratification. Or young people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds expect to complete less ambitious educational pathways than those from more advantageous socioeconomic backgrounds, even after controlling for ability (Jackson et al. Citation2007; Erikson Citation2016). It is likely that these social differentials in educational expectations and decisions net of ability are related to differences in parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources.

For several reasons, the focus in this paper is on higher education. First of all, from a social mobility perspective, attainment of higher education is considered as an opportunity for students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to become upward mobile. This especially holds in the presence of institutional reforms aimed at making educational systems more meritocratic (Tieben and Wolbers Citation2010b). For students from more privileged families, in contrast, obtaining a degree in higher education is a necessity to minimize, from an intergenerational perspective, the risk of a loss; that is, of social demotion. To put it another way, young people from different social origins have different reference points and, for that reason, their educational expectations regarding higher education vary. This makes the investigation of the effect of social origin on young people’s expectations of higher education an important one. In addition, with evolving technological development, globalization and economic competition, a degree in higher education has become more important than ever before for young people and is a prerequisite nowadays for a stable labour market position and economic independence. Expectations of completing higher education among young people are therefore important to study, given their strong association with later educational and occupational attainment, and related outcomes in other life domains, such as family and household formation (Wolbers Citation2007). Finally, the focus on higher education is consistent with previous research in this field (Buchmann and Park Citation2009; McDaniel Citation2010; Parker et al. Citation2016).

The Netherlands is an interesting case to examine the effect of parental education, as a measure of social origin, on young people’s expectations regarding higher education. First, the Netherlands can be characterized as a highly stratified educational system (de Graaf and Ganzeboom Citation1993) in which students are sorted into different educational tracks at an early age (during the transition from primary to secondary education, at the age of 12 years). Given the fact that at this stage in the educational career parents are still rather important for the choice of a school type in secondary education (Jacob and Tieben Citation2009; Tieben and Wolbers Citation2010a), and because this track pre-sorts and determines the further educational career, expectations regarding future educational decisions are strongly connected with social origin. Second, there is hardly any research available on the relationship between social origin and young people’s educational expectations regarding higher education that specifically focuses on the Netherlands. Notably exceptions are the studies by Need and de Jong (Citation2000) and by Tolsma, Need, and de Jong (Citation2010), but the data used in these articles are rather outdated (collected in the 1990s) and do not contain information on parents’ cultural and educational resources. In this respect, the current paper fills in a knowledge gap.

The data used for the empirical analysis come from the Programme for International Study Assessment (PISA) 2018 (OECD Citation2019). PISA 2018 was the seventh round of the international assessment since the programme was launched in 2000. Every PISA round assesses the knowledge and skills of 15 year olds in reading, mathematics and science, and other school performance related indicators such as grade. In addition, information is collected on the students’ socioeconomic background, including data on their family situation, and educational and occupational expectations. Despite the large number of countries involved in the PISA 2018 survey, the empirical analysis of this paper solely focuses on the Netherlands, as already discussed.

Theoretical background

Primary and secondary effects of social stratification

Much research on social differentials in educational attainment refers to the work of Boudon (Citation1974) and the distinction he made between primary and secondary effects of social stratification. Primary effects can be interpreted as influences, including genetic ones, that are expressed through the uneven school performance of students from different social origins. Or, in terms of educational expectations, students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds have higher expectations due to their better school results. Secondary effects refer to the residual impact of social origin that exists over and above school performance (related indicators), thereby likely reflecting an anticipatory dimension of educational decision-making (Karlson and Holm Citation2011). Or formulated differently, two individuals with the same school performance but from different socioeconomic backgrounds do not have equal educational expectations nor make the same educational decisions (Jackson et al. Citation2007). In short, it is thus hypothesized that only part of the association between social origin and young people’s expectations to complete higher education is related to differences in school performance (related indicators).

The role of parental resources

From cultural and social reproduction theory (Bourdieu Citation1973; Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1977), the role of parental resources is considered the dominant explanation for the existence of secondary effects of social stratification. It is supposed that several types of parental resources directly affect educational decisions regarding study choice after secondary education and explain the social origin effect on these conditional decisions (de Graaf and Wolbers Citation2003; Tieben and Wolbers Citation2010b; Strømme and Helland Citation2020). The assumption is that these parental resources also matter with respect to the explanation of social inequalities in educational expectations.

First, parents’ economic resources are likely to play a role (Conley Citation2001). Higher education studies take longer than educational programmes in vocational education and are, therefore, more costly, not only because of the direct costs of education involved (cost of living, tuition fees, books, a computer), but also because there are indirect or opportunity costs (loss of income) during the period in which one studies (de Graaf Citation1986; Gambetta Citation1987). Given that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have less economic resources from their parents to cover the costs of studying, their ambitions to achieve a degree in higher education are lower.

Second, it can be predicted that cultural resources of the parents are important. The cultural capital hypothesis argues that students, for whom the difference between the culture at home and the culture at schools for secondary education is too great, perform less well than those who were raised with a liking for learning, reading and formal cultural expression (Bourdieu Citation1973; DiMaggio Citation1982; de Graaf, de Graaf, and Kraaykamp Citation2000; Jaeger Citation2009). Essentially, the effect of cultural capital on educational attainment is exerted in three ways (Kalmijn and Kraaykamp Citation1996; see also van de Werfhorst and Hofstede Citation2007): children of families with a lot of cultural capital learn better; these children have been acquainted with abstract and intellectual matters; and they have more frequent and positive interactions with their teachers. In particular, the latter aspect matters with respect to the explanation of the social origin effect on young people’s expectations to attend and complete higher education, especially university education. Cultural capital operates as a marker or signal that secondary school teachers use in their recommendations regarding further educational choices of young people that are not entirely based on their prior school results, cognitive ability and motivation (Timmermans et al. Citation2018). They might encourage the educational aspirations of equally achieving students, subsequently leading to more ambitious educational expectations and decisions, only if these students exhibit the cultural signs (knowledge, tastes and preferences) of the dominant status groups (Valdés Citation2022).

Third, parents’ educational resources are expected to be relevant (Hampden-Thompson, Guzman, and Lippman Citation2013). These refer to human and material assets that enhance academic skills and orientations (Roscigno and Ainsworth-Darnell Citation1999). The human component has to do with the educational support that parents can give to their children. This concerns, for instance, the support of parents regarding educational efforts and achievements of children, but also their support for them when they face difficulties at secondary school (McNeal Citation1999; Schaub Citation2010). The material component consists of household educational resources, such as a quiet place to study at home, of which it is likely that privileged families have a greater ability to invest in than less privileged ones (Teachman Citation1987). Therefore, it is predicted that – due to less educational resources from their parents – students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have lower aspirations with regard to attainment of higher education.

Relative risk aversion

An alternative explanation for the existence of secondary effects of social stratification comes from rational action theory (Goldthorpe Citation1996; Breen and Goldthorpe Citation1997). In this approach, the prime factor conditioning educational expectations and decisions is the avoidance of downward social mobility. In general, parents want to avoid social demotion and therefore strive for at least the same educational level for their children as their own. Although this social demotion motive works in all families, it has different consequences for children from varying social origin. Individuals with similar school performance but from different social origins face different returns from completing, for instance, higher education. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds can reach their parents’ educational level more easily than those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, which makes the pressure to obtain a degree in higher education less severe for the former group. Reluctance to enter higher educational levels than necessary may also stem from the perception that the benefits of social promotion do not outweigh the additional investment in education. As a result, young people from higher socioeconomic backgrounds are more ambitious than those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds at the same level of performance (Valdés Citation2022).

Unfortunately, we do not have adequate measures available in the dataset used for the empirical analysis to directly test the mechanisms postulated from the aforementioned relative risk aversion model of educational inequality. However, we believe that the social differentiation in perceived chances of success, costs and benefits of educational options that lead to different ambitions regarding educational expectations and decisions are picked up to a considerable extent by differences in the amount of resources parents possess for supporting the educational career of their child(ren). In fact, the secondary effects left unexplained after taking parental resources into account indicate the extent to which these resources do not absorb differences in educational ambitions related to social origin net of ability and, therefore, offer indirect evidence for rational action theory.

Methodology

Data

To test these hypotheses, we used data from the 2018 round of the PISA carried out by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The PISA is a triennial survey among young people around the world that assesses the extent to which they have acquired key knowledge and skills (in particular with regard to reading, mathematical and scientific literacy) essential for full participation in social and economic life. It was implemented in 2000 in 43 countries. In 2018, 79 countries participated in the PISA. The surveys target the population of 15-year-old students enrolled in school, regardless of grade or educational programme. A two-stage stratified sampling design (first of schools and then of students within sampled schools) achieved a high quality of coverage of the 15 year olds in each country.

Computer-based tests were used in most countries, with assessments lasting a total of two hours. Students also answered a background questionnaire, which took some 35 minutes to complete. The questionnaire sought information about the students themselves, their attitudes, dispositions and beliefs, their homes, and their school and learning experiences. About 710,000 students completed the assessment in 2018, representing about 31 million 15 year olds in the schools of the 79 participating countries (see OECD [Citation2019] for more technical details about the survey methodology and data collection).

For the purpose of this paper, we only analysed data from the Netherlands.Footnote1 In total, 4765 students in 156 schools for secondary education completed the assessment, representing 190,281 students aged 15 years (91% of the total population of 15 year olds in the Netherlands). The fieldwork took place between 5 March and 27 April 2018. The weighted participation (response) rate of originally sampled schools was 90%, where non-participating sampled schools have been substituted with ‘replacement schools’ identified at the time of school sampling to meet sample size and response rate requirements. More details about the PISA 2018 data collection in the Netherlands can be found in Gubbels et al. (Citation2019).

Dependent variables

Young people’s expectations of higher education were measured by questioning whether 15-year-old students expected to complete higher education (higher vocational education [hbo in Dutch] or university [wo in Dutch]). This dependent variable takes the value 1 if this was confirmed, and 0 if not. It was defined for the whole sample. In addition, the expectation of completing university (value 1) instead of higher vocational education (value 0) was analysed for those who expected to complete higher education. This is our second dependent variable.

Independent variable

In this paper, parental education was used as a measure of social origin. We focused on this characteristic of social origin (and not, for instance, on social class or income, although all three indicators contribute to primary and secondary effects of social stratification), as parental education can be considered as the most important indicator for parents’ ability to educationally support their children (for instance, with their homework) and parents’ familiarity with the educational system. This allows them to give more or less informed advice on their children’s choices regarding the educational career (Bukodi and Goldthorpe Citation2013; see also Blossfeld Citation2018).Footnote2 Moreover, by looking at the relationship between parents’ education and their children’s education (educational expectations), we can explicitly address the intergenerational transmission of educational inequality. Although both parents’ level of education matters when explaining their children’s education, the most important effect is that of the parent with the highest educational attainment (van Hek, Kraaykamp, and Wolbers Citation2015). For that reason, we took the parent with the highest educational level (commonly referred to as the dominance approach [Erikson Citation1984]). Four levels of education were distinguished in the analysis: lower secondary education at most; upper secondary education; higher vocational education; and university.

Mediator variables

In the PISA, 15-year-old students are assessed in the domains of reading, mathematics and science. Given the strong correlations between the scores on these three domains (of 0.90 and higher) and to avoid multicollinearity in the analysis, the average of the scores was calculated in order to obtain an overall measure of scholarly ability (Cronbach’s alpha is 0.97). In addition, two other school performance related indicators were taken into account to establish the portion of the total effect of social origin that operates via primary effects. First, grade was included in the analysis. This refers to the grade compared to the modal grade 15-year-old students were in, and ranges from −3 to 2 school years. Second, the type of programme students were in was added: academic programme (value 1) versus pre-vocational programme (value 0).

Furthermore, measures of parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources were treated as mediator variables to interpret the remaining effect of social origin. Parents’ economic resources were operationalized by the presence and number of various material goods in the home: televisions, cars, rooms with a bath or shower, cell phones with Internet access and computers. Cronbach’s alpha of this scale consisting of five items is 0.60. Students originally responded on a scale from 1 to 4, but the unweighted mean scores were re-scaled to a 0–1 range. Parents’ cultural resources were measured by two indicators. First, the number of books at home was considered.Footnote3 The range of this variable runs from 0 to more than 500 books. Second, the possession of classic literature, books of poetry, works of art, books on art, music or design and musical instruments was mapped and constructed to a scale. Cronbach’s alpha of this six-item scale is 0.64. The mean scores range from 0 to 1. Parents’ educational resources were also operationalized by two indicators. In addition to a measurement instrument for parental support for school (with three items – ‘my parents support my educational efforts and achievements’, ‘my parents support me when I am facing difficulties at school’ and ‘my parents encourage me to be confident’ – and four response categories ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’; Cronbach’s alpha is 0.87), an index summing up educational resources available at home (a desk to study at, a quiet place to study, a compute to use for school work, books to help with school work and a dictionary) was created (Cronbach’s alpha is 0.51). The scores for both indicators of parents’ educational resources range from 0 to 1.

Control variables

Finally, gender (with value 1 for female students) and migrant status (with value 1 for students who themselves or at least one of their parents were born outside the Netherlands, i.e. immigrants) were considered as relevant socio-demographic control variables.

Analytical strategy

In order to examine the effect of parental education on young people’s expectations to complete a degree in higher education, we estimated linear probability models with robust standard errors. This approach corrects the standard errors of the models’ estimated coefficients to account for conditional heteroskedasticity caused by the binary character of the dependent variables. The advantage of the linear probability model over the logit model is that coefficients across (nested) models within a sample can be compared and that they immediately can be interpreted in terms of effects on probabilities instead of first calculating, for instance, average marginal effects from the logit model coefficients (Mood Citation2010; see also Bernardi and Cebolla-Boado Citation2014).

Five models were estimated. Model 1 included parental education, as our measure of social origin, to assess the total (or bivariate) effect of social origin on young people’s expectations to complete a degree in higher education. In Model 2, we took gender and migrant status as relevant socio-demographic variables into account. Model 3 added scholarly ability, and this was used to disentangle the secondary effects of social stratification. It presents the direct social origin effect of young people’s expectations of completing higher education net of scholarly ability. The two other school performance related indicators were then added in Model 4 as a useful complement for scholarly ability and to further establish secondary effects of social stratification. In Model 5, finally, we included the various measures of the parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources to determine the degree to which the established secondary effects were explained by the unequal availability of parental resources for students from different social origins.

Results

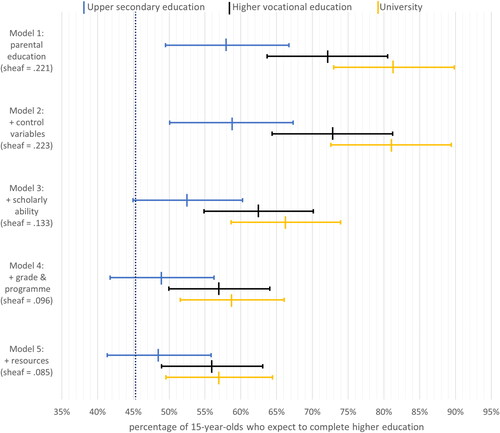

We started to estimate the effect of parental education on young people’s expectations to complete (any kind of) higher education. The results are summarized in , while the models in full are reported in of Appendix 1. The observed likelihood of expecting to complete a degree in higher vocational education or university education for 15-year-old students with parents who have attained lower secondary education at most is 45% (i.e. the reference category; presented as the vertical dotted line in ). Model 1 reports that for students with parents who have obtained upper secondary education, the probability of expecting to complete higher education is 13 percentage points higher and reaches 58% (45% + 13%) (see the blue horizontal line indicating the estimated effect and the 95% confidence interval). For students with parents who finished higher vocational education, the probability of expecting to complete higher education increased by 27 percentage points (see the black horizontal line indicating the estimated effect and the 95% confidence interval) and for students with university educated parents this increase is 36 percentage points (see the yellow horizontal line indicating the estimated effect and the 95% confidence interval). The observed percentages are 72% and 81%, respectively. These differences reflect the total social origin effect. Heise’s sheaf coefficient (Heise Citation1972), used to summarize the effect of social origin as the combined effects of the various categories of parental educational level, is 0.221. After controlling for gender and migration status in Model 2, the estimated probabilities (and sheaf coefficient) remained almost unchanged.

Figure 1. Effect of parental education on expectations of 15 year olds to complete higher education.

Source: Dutch data from the PISA 2018 survey, authors’ own calculations.

In Model 3, where scholarly ability was added, we see that 40% of the total effect of social origin operates via primary effects ((1 − 0.133/0.221) × 100). After adding the two other school performance related indicators in Model 4, the percentage of the total effect of social origin explained further increased to 57%. So, scholarly ability accounts for a large part of that mediation, but grade and type of programme additionally interpret a substantial part of the total social origin effect on the likelihood of expecting to complete higher education. All three measures of scholastic achievement have a strong positive effect on students’ expectations to complete higher education. The remaining, direct effect of social origin refers to secondary effects of social stratification. It consists of 43% (100% − 57%) of the total social origin effect on the likelihood of expecting to complete higher education.

In Model 5, the various measures of the parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources were included. The percentage of the total effect of social origin explained now amounts to 62%. So, parental resources additionally explain only 5% of the total social origin effect. Also, in terms of secondary effects of social stratification, the contribution of parental resources is small. They are a weak mediator of secondary effects. Around 12% ((1 − 38/43) × 100) of the secondary effects is explained by the parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources. The most substantial contribution was made by the parents’ economic resources, which has a significant impact on the students’ expectations to complete a degree in higher education.

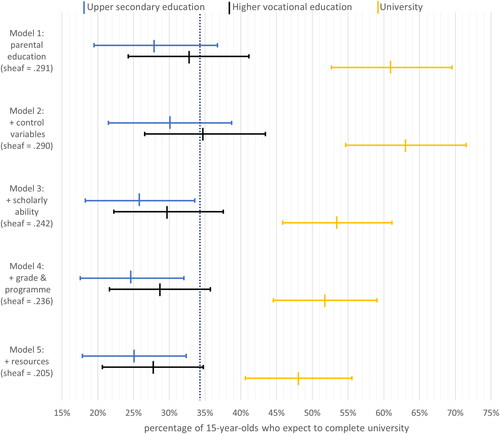

Results of the analysis regarding the effect of parental education on the expectation of graduating from university instead of higher vocational education, conditional upon the expectation to complete any kind of higher education, are presented in . Once again, full models can be found in Appendix 1 (). Model 1 shows that among all 15-year-old students who expect to complete higher education, the likelihood of expecting to get a university degree is 34% for those whose parents have attained lower secondary education at most (see the dotted vertical line). For students with parents who have finished upper secondary education or higher vocational education, similar percentages are observed. Only for students whose parents have attained university education is the likelihood of expecting to get a university degree significantly larger. Their probability of expecting to graduate from university is 27 percentage points higher than the corresponding probability for those whose parents only have a diploma at the lower secondary level. These results remained almost unchanged after the effects of gender and migration status were taken into account (see Model 2).

Figure 2. Effect of parental education on expectations of 15 year olds to complete university (for those who expect to complete higher education).

Source: Dutch data from the PISA 2018 survey, authors’ own calculations.

Model 3 presents the effect of social origin on 15-year-old students’ expectations to graduate from university instead of higher vocational education net of scholarly ability. As is shown in , part of the total effect of social origin is mediated by this characteristic of scholastic achievement. To be precise, 17% of the total social origin effect is statistically explained by scholarly ability. After accounting for the two other performance related indicators in Model 4, the explained effect of social origin is 19%. Once again, scholarly ability accounts for a larger part of the mediation than grade and type of programme. More generally, the share of the total social origin effect that operates via primary effects is relatively small. The largest part of the total social origin effect remained direct after controlling for the three indicators of scholastic achievement. According to Model 4, 81% of the total social origin effect refers to secondary effects of stratification.

Parental resources partly explain the secondary effects of stratification. On the basis of Model 5, it is calculated that 13% of the remaining social origin effect as presented in Model 4 is mediated by the parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources. In particular, parental support for school and cultural possessions matter with respect to the likelihood of expecting to get a university degree instead of a diploma in higher vocational education among those who expect to complete higher education. Despite the role played by these parental resources, a large part of the (direct) social origin effect on 15-year-old students’ expectations to graduate from university (relative to higher vocational education) is left unexplained.

Conclusions

In this paper, the effect of social origin, operationalized as parental education, on expectations of 15 year olds to complete a degree in Dutch higher education was investigated. In particular, the interpretation of this effect – as comes about through primary and secondary effects of social stratification, according to Boudon (Citation1974) – was determined by testing specific explanations for these social differentials in expectations. For the empirical analysis, the PISA 2018 data for the Netherlands were used.

The results revealed that there is a large effect of parental education on the likelihood of expecting to obtain a degree in higher vocational education or university for 15 year olds in the Netherlands. The higher the level of education attained by their parents, the larger were young people’s expectations of completing higher education. A substantial part of this effect, considered as the total effect of social origin on the expectation to complete higher education, is mediated by scholarly ability; grade and type of programme additionally interpret the social origin effect. Taken together, a bit more than half of the total social origin effect operates via primary effects of social stratification. The remaining, direct effect of social origin refers to secondary effects of social stratification: students with the same school performance have different educational expectations regarding higher education that are strongly correlated with their social origin. In other words, when comparing two students with the same scholastic achievement but from different socioeconomic backgrounds, the student from a lower socioeconomic background less likely expects to complete higher education than the student from a higher socioeconomic background. The role of secondary effects of social stratification is rather substantial. Only a small part of the secondary effects, however, is explained by the parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources.

Also with regard to the expectation of graduating from university instead of higher vocational education, conditional upon the expectation to complete any kind of higher education, an effect of parental education was found, but only for students whose parents have attained university. Around one-fifth of this effect, regarded as the total social origin effect, is explained by school performance related indicators. So, the major effect of social origin consists of secondary effects of social stratification. Parental resources only partly explain these secondary effects. A large part of the direct social origin effect on young people’s expectations to graduate from university (relative to higher vocational education) is left unexplained.

In summary, then, it can be concluded that to a large extent the social origin effect on expectations of 15 year olds to complete higher education in the Netherlands refers to secondary effects of social stratification. Two students with the same school performance but from different socioeconomic backgrounds hold different expectations (and subsequently make different choices) with regard to attainment of higher education due to social origin-related preferences, resources and constraints.

These secondary effects can also be described in terms of underachievement. The results revealed that students with parents with low education (or non-tertiary education) have lower expectations regarding higher education, and, for that reason, are likely to perform less well than they could, given their cognitive learning potential, due largely to their low social origin. With better socioeconomic circumstances at home, these students might have the potential to expect and subsequently achieve more than they actually do. Much work thus remains for policies aimed at preventing and combating underachievement and, more generally, educational disadvantage, despite a tradition of educational disadvantage policy in the Netherlands for more than 50 years, where various national interventions have been designed and implemented, and huge budgets have been invested (Driessen Citation2013).

Parental resources only slightly explain the direct social origin effect net of school performance. For the largest part, the secondary effects of social stratification remain unexplained after taking parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources into account. This result does not imply that parental resources do not matter at all with regard to (the explanation of the social origin effect on) educational expectations. Presumably, cultural and social reproduction mainly work through the primary effects (van de Werfhorst and Hofstede Citation2007). Social origin is positively related to parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources and given that these parental resources positively affect school performance, parental resources partly intermediate the effect of social origin on school performance. In other words, the observed small effects (and little explanatory power) of parental resources (in interpreting the effect of social origin) on young people’s expectations to complete a degree in higher education net of school performance would have been greater without statistically controlling for school performance (related indicators). Additional empirical evidence (results are not shown, but available on request from the authors) supports this argument: all indicators of parents’ economic, cultural and educational resources have a positive effect on young people expectations to complete a degree in higher education, and these parental resources explain the social origin effect to a considerably larger extent than in the case of controlling for school performance.

Indirectly, the remaining secondary effects demonstrate the importance of costs and benefits of educational options that children and their parents weigh in educational expectations and decision-making (Breen and Goldthorpe Citation1997). Unfortunately, the PISA data used in this paper did not offer the opportunity to empirically investigate this claim. For that reason, it would be helpful in future PISA cycles for adequate and fine-grained measures to be developed to directly test the mechanisms postulated from the relative risk aversion model of educational inequality to explain social differentials in young people’s expectations to complete higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 A multi-national samples approach (or cross-national comparison) based on the PISA to get more (cross-country) variation (in the effect of social origin) on the dependent variables to be analysed would have been possible and has been dealt with previously (Buchmann and Park Citation2009; Parker et al. Citation2016), but the focus here is on the understanding of inequality in educational expectations by testing specific (micro-level) explanations for the social origin effect in a particular case, that is, the Netherlands, for which the national PISA data offer a good opportunity to do so.

2 Also for a more pragmatic reason, the focus was on parental education, as only a limited measure of social class and no measure of income was available in the PISA 2018 survey.

3 The number of books at home is used in many large-scale assessment studies organized by the OECD (not only in the PISA, but also in the Programme for the International Assesment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) for instance) as a proxy for parents’ cultural resources. However, it has been subject to discussion (Sieben and Lechner Citation2019), especially since this single-item measure only covers one aspect of cultural capital in the Bourdieusian approach (i.e. objectified cultural capital) and its measurement quality has, apart from its face validity, hardly been systematically scrutinized.

References

- Beal, S. J., and L. J. Crockett. 2010. “Adolescents’ Occupational and Educational Aspirations and Expectations: Links to High School Activities and Adult Educational Attainment.” Developmental Psychology 46 (1): 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017416.

- Bernardi, F., and H. Cebolla-Boado. 2014. “Previous School Results and Social Background: Compensation and Imperfect Information in Educational Transitions.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct029.

- Blossfeld, P. N. 2018. “A Multidimensional Measure of Social Origin: Theoretical Perspectives, Operationalization and Empirical Application in the Field of Educational Inequality Research.” Quality & Quantity 53 (3): 1347–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0818-2.

- Boudon, R. 1974. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality. New York: Wiley.

- Bourdieu, P. 1973. “Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction.” In Knowledge, Education and Cultural Change, edited by R. Brown, 71–112. London: Tavistock.

- Bourdieu, P., and J. C. Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture. London: Sage.

- Breen, R., and J. H. Goldthorpe. 1997. “Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a Formal Action Theory.” Rationality and Society 9 (3): 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346397009003002.

- Buchmann, C., and H. Park. 2009. “Stratification and the Formation of Expectations in Highly Differentiated Educational Systems.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 27 (4): 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2009.10.003.

- Bukodi, E., and J. H. Goldthorpe. 2013. “Decomposing ‘Social Origins’: The Effects of Parents’ Class, Status, and Education on the Educational Attainment of Their Children.” European Sociological Review 29 (5): 1024–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs079.

- Conley, D. 2001. “Capital for College: Parental Assets and Postsecondary Schooling.” Sociology of Education 74 (1): 59–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673145.

- DiMaggio, P. 1982. “Cultural Capital and Social Success: The Impact of Status Culture Participation on the Grades of High School Students.” American Sociological Review 47 (2): 189–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094962.

- de Graaf, N. D., P. M. de Graaf, and G. Kraaykamp. 2000. “Parental Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment in The Netherlands: A Refinement of the Cultural Capital Perspective.” Sociology of Education 73 (2): 92–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673239.

- de Graaf, P. M. 1986. “The Impact of Financial and Cultural Resources on Educational Attainment in The Netherlands.” Sociology of Education 59 (4): 237–246. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112350.

- de Graaf, P. M., and H. B. G. Ganzeboom. 1993. “Family Background and Educational Attainment in The Netherlands for the 1891-1960 Birth Cohorts.” In Persistent Inequality. Changing Educational Attainment in Thirteen Countries, edited by Y. Shavit and H.-P. Blossfeld, 75–99. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- de Graaf, P. M., and M. H. J. Wolbers. 2003. “The Effects of Social Background, Sex, and Ability on the Transition to Tertiary Education.” The Netherlands’ Journal of Social Sciences 39: 172–201.

- Driessen, G. 2013. De bestrijding van onderwijsachterstanden. Een review van opbrengsten en effectieve aanpakken. Nijmegen: Instituut voor Toegepaste Sociale Wetenschappen.

- Erikson, R. 1984. “Social Class of Men, Women and Families.” Sociology 18 (4): 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038584018004003.

- Erikson, R. 2016. “Is It Enough to Be Bright? Parental Background, Cognitive Ability and Educational Attainment.” European Societies 18 (2): 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1141306.

- Gambetta, D. 1987. Were They Pushed or Did They Jump? Individual Decision Mechanisms in Education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goldthorpe, J. H. 1996. “Class Analysis and the Reorientation of Class Theory: The Case of Persisting Differentials in Educational Attainment.” The British Journal of Sociology 47 (3): 481–505. https://doi.org/10.2307/591365.

- Gottfredson, L. S. 1981. “Circumscription and Compromise: A Developmental Theory of Occupational Aspirations.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 28 (6): 545–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.6.545.

- Gubbels, J., A. M. L. van Langen, N. A. M. Maassen, and M. R. M. Meelissen. 2019. Resultaten PISA-2018 in vogelvlucht. Enschede: Universiteit Twente; Nijmegen: Expertisecentrum Nederlands & KBA Nijmegen.

- Hampden-Thompson, G., L. Guzman, and L. Lippman. 2013. “A Cross-National Analysis of Parental Involvement and Student Literacy.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 54 (3): 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715213501183.

- Heise, D. R. 1972. “Employing Nominal Variables, Induced Variables, and Block Variables in Path Analysis.” Sociological Methods & Research 1 (2): 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912417200100201.

- Jackson, M., R. Erikson, J. H. Goldthorpe, and M. Yaish. 2007. “Primary and Secondary Effects in Class Differentials in Educational Attainment: The Transition to A-Level Courses in England and Wales.” Acta Sociologica 50 (3): 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307080926.

- Jacob, M., and N. Tieben. 2009. “Social Selectivity of Track Mobility in Secondary Schools. A Comparison of Intra-Secondary Transitions in Germany and The Netherlands.” European Societies 11 (5): 747–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690802588066.

- Jaeger, M. M. 2009. “Equal Access but Unequal Outcomes: Cultural Capital and Educational Choice in a Meritocratic Society.” Social Forces 87 (4): 1943–1971. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0192.

- Kalmijn, M., and G. Kraaykamp. 1996. “Race, Cultural Capital, and Schooling: An Analysis of Trends in the United States.” Sociology of Education 69 (1): 22–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112721.

- Karlson, K. B., and A. Holm. 2011. “Decomposing Primary and Secondary Effects: A New Decomposition Method.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 29 (2): 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2010.12.005.

- Li, W., and Y. Xie. 2020. “The Influence of Family Background on Educational Expectations: A Comparative Study.” Chinese Sociological Review 52 (3): 269–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2020.1738917.

- Madden, T. J., P. S. Ellen, and I. Ajzen. 1992. “A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 18 (1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292181001.

- McDaniel, A. 2010. “Cross-National Gender Gaps in Educational Expectations: The Influence of National-Level Gender Ideology and Educational Systems.” Comparative Education Review 54 (1): 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1086/648060.

- McNeal, R. B. 1999. “Parental Involvement as Social Capital: Differential Effectiveness on Science Achievement, Truancy, and Dropping out.” Social Forces 78 (1): 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/78.1.117.

- Mood, C. 2010. “Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do about.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006.

- Need, A., and U. de Jong. 2000. “Educational Differentials in The Netherlands. Testing Rational Action Theory.” Rationality and Society 13 (1): 71–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346301013001003.

- OECD (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development). 2019. PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Parker, P. D., J. Jerrim, I. Schoon, and H. W. Marsh. 2016. “A Multination Study of Socioeconomic Inequality in Expectations for Progression to Higher Education: The Role of between-School Tracking and Ability Stratification.” American Educational Research Journal 53 (1): 6–32. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831215621786.

- Roscigno, V. J., and J. W. Ainsworth-Darnell. 1999. “Race, Cultural Capital, and Educational Resources: Persistent Inequalities and Achievement Returns.” Sociology of Education 72 (3): 158–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673227.

- Schaub, M. 2010. “Parenting for Cognitive Development from 1950 to 2000: The Institutionalization of Mass Education and the Social Construction of Parenting in the United States.” Sociology of Education 83 (1): 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040709356566.

- Sewell, W. H., A. O. Haller, and A. Portes. 1969. “The Educational and Early Occupational Attainment Process.” American Sociological Review 34 (1): 82–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092789.

- Sieben, S., and C. M. Lechner. 2019. “Measuring Cultural Capital through the Number of Books in the Household.” Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences 1 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42409-018-0006-0.

- Strømme, T. B., and H. Helland. 2020. “Parents’ Educational Involvement: Types of Resources and Forms of Involvement in Four Countries.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (5): 993–1011. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3609.

- Teachman, J. D. 1987. “Family Background, Educational Resources, and Educational Attainment.” American Sociological Review 52 (4): 548–557. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095300.

- Tieben, N., and M. H. J. Wolbers. 2010a. “Success and Failure in Secondary Education: Socio-Economic Background Effects on Secondary School Outcome in The Netherlands, 1927-1998.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 31 (3): 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425691003700516.

- Tieben, N., and M. H. J. Wolbers. 2010b. “Transitions to Post-Secondary and Tertiary Education in The Netherlands: A Trend Analysis of Unconditional and Conditional Socio-Economic Background Effects.” Higher Education 60 (1): 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9289-7.

- Timmermans, A. C., H. de Boer, H. T. A. Amsing, and M. P. C. van der Werf. 2018. “Track Recommendation Bias: Gender, Migration Background and SES Bias over a 20-Year Period in the Dutch Context.” British Educational Research Journal 44 (5): 847–874. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3470.

- Tolsma, J., A. Need, and U. de Jong. 2010. “Explaining Participation Differentials in Dutch Higher Education: The Impact of Subjective Success Probabilities on Level Choice and Field Choice.” European Sociological Review 26 (2): 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp061.

- Valdés, M. T. 2022. “Unequal Expectations? Testing Decisional Mechanisms for Secondary Effects of Social Origin.” Social Science Research 105: 102688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102688.

- van de Werfhorst, H. G., and S. Hofstede. 2007. “Cultural Capital or Relative Risk Aversion? Two Mechanisms for Educational Inequality Compared.” The British Journal of Sociology 71 (1): 47–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00157.x.

- van Hek, M., G. Kraaykamp, and M. H. J. Wolbers. 2015. “Family Resources and Male-Female Educational Attainment. Sex-Specific Trends for Dutch Cohorts (1930–1984).” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 40 (1984): 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2015.02.001.

- Wolbers, M. H. J. 2007. “Employment Insecurity at Labour Market Entry and Its Impact on Parental Home Leaving and Family Formation. A Comparative Study among Recent Graduates in Eight European Countries.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 48 (6): 481–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715207083339.

- Zimmermann, T. 2019. “Social Influence or Rational Choice? Two Models and Their Contribution to Explaining Class Differentials in Student Educational Aspirations.” European Sociological Review 36: 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz054.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Effect of social origin on expectations of 15 year olds to complete higher education; linear probability models with robust standard errors (N = 3.623).

Table A2. Effect of social origin on expectations of 15 year olds to complete university (for those who expect to complete higher education); linear probability models with robust standard errors (N = 2.537).