ABSTRACT

The Rivers of Reading methodology has been used previously to explore children’s reading development, but very little research focusing on multilingual children exists. Similarly, reading for pleasure in multiple languages has received little attention. This paper addresses both these gaps. Seven children aged 8-13, across six multilingual families in England, constructed Rivers of Reading – a critical incident technique linked to reading resources and experiences. These were supported by three interviews per family, over a period of 10–12 months, with children sharing detailed narratives linked to their reading and languages. This data set was coded to explore what influenced children’s choices for inclusion of resources in their narratives, as well as surrounding strategies and experiences. The study found that children had complex reasons for the inclusion of books and other reading material, many of which linked to what books represented for them in their language and literacy development. Asynchronous literacy development frustrated several children, but many had innovative ways to overcome these in their journey towards biliteracy. The Rivers of Reading methodology is particularly useful in exploring multilingual children’s reading pathways, facilitating family discussion around frustrations, support needs, and positive memories.

Introduction

Books remain the favourite heritage language resource among multilingual families (Little Citation2019). More books in the home are traditionally assumed to lead to more reading, which in turn results in a larger vocabulary, higher levels of grammatical accuracy, and greater reading comprehension (Krashen Citation1993). With many multilingual couples equating bilingual parenting with ‘good’ parenting (King and Fogle Citation2006), the early years are often shaped by familial literacy practices in the heritage language (Song Citation2016), provided there is sufficient access to resources (Little Citation2017).

School, for many multilingual families, changes the focus to literacy development in the school language, with children sometimes questioning the status quo of the heritage language (Little Citation2020). England, where the study took place, has no firm curriculum commitment towards home language support, despite approximately 20% of pupils coming having English as an additional language (Statista Citation2018). Biliteracy development is thus often asynchronous, although not necessarily (Kenner Citation2004). There remains a lack of in-depth, qualitative studies which explore long-term development of biliteracy, particularly outside the early years, and in the context of reading for pleasure (Worthy, Nuñez, and Espinoza Citation2016). With increasing super-diversity (Vertovec Citation2007), such studies are important at both national and global level, contributing to our understanding of multilingualism across the lifespan. This project, working with seven children aged 8–13 years of age, across six families, addresses this gap, asking

How do multilingual children and families negotiate their reading over time?

What are critical incidents linked to multilingual reading?

To what extent can the Rivers of Reading methodology help multilingual families in discussing multilingual reading?

The study explored children’s reading experiences retrospectively, through Cliff Hodges’ (Citation2010) ‘Rivers of Reading’ approach, with children creating collages, PowerPoints or displays which chronicled their experiences to date. These were contextualised with three interviews per family, involving at least the child plus one parent, over 10–12 calendar months. The study makes a significant contribution to our understanding of older multilingual children’s reading habits and attitudes, as well as highlighting biliteracy development in the child’s life.

Biliteracy and asynchronous biliteracy

Biliteracy has received interest across the early years (Kenner Citation2004; Moll, Saez, and Dworin Citation2001; Song Citation2016) and as part of complementary schooling (Creese, Wu, and Blackledge Citation2009). Research with older children focuses primarily on new arrivals and emergent bilinguals (Menken Citation2013). However, there is evidence that, in the upper years of primary education, most reading switches to the societal/school language (Worthy, Nuñez, and Espinoza Citation2016).

Biliteracy development is influenced through context, content, and media, as part of the fluid relationship between bilingualism and literacy (Hornberger Citation2004). Hornberger’s continua model of biliteracy is particularly relevant here, since ‘although one can identify (and name) points on the continuum, those points are not finite, static, or discrete’ (Hornberger Citation2004, 156). Children’s Rivers of Reading highlight some of these points, and facilitate exploration in relation to overall biliteracy development.

Moll, Saez, and Dworin (Citation2001) point out that, while literacy development is an individual accomplishment, it is not an accomplishment achieved in isolation, but as part of home and school literacy practices. In England, without a clear school policy dedicated to multilingualism, parents employ often creative measures to support bilingual and biliterate development, including home teaching, use of technology, heritage language schools, visits to a country where the heritage language is spoken, and printed and audio-visual resources (Little Citation2020).

Accessing appropriate reading materials forms a vital component of biliteracy development (Krashen Citation1993). A positive attitude to reading, and reading for pleasure in the heritage language, are necessary to avoid language shift (Tse Citation2001). The mutually beneficial relationship leads to the ‘Matthew Effect’ (Stanovich Citation1986), where good readers get better and poor readers fall further behind. Since heritage language reading is typically less well organised, outside national curricula and formal schooling, this relationship is particularly vulnerable.

The research so far shows that biliterate development is difficult, outside a supportive social network or education context. In fact, Tse (Citation2001) identifies a supportive peer group as the single most influential factor in supporting biliteracy. This peer group, however, is not necessarily geographically close to the family, with parents having to take on a major supportive role as their children ‘walk in two cultural worlds’ (Li Citation2006, 358).

School effect on biliteracy and language shift

The concept of first and second language acquisition can be problematic for multilingual children, due to familial language shift (Fishman Citation1964; Tse Citation2001). While Veltman (Citation1983) considers familial language shift – one language taking over another – to occur over three generations, more recent research (Pease-Alvarez Citation2002) shows family language shift within a single generation, with changes in the sociocultural structure influencing children’s language proficiency. Within this context, the beginning of formal education forms a key critical incident (Flanagan Citation1954; Nylén and Isomöttönen Citation2017), necessitating a closer look at the links between school, biliteracy, and language shift.

Despite researchers long arguing for the integration of home literacies into our understanding of literacy practices (Gregory Citation1998; Street and Street Citation1991), the ‘value’ assigned to literacy practices remains almost universally driven by school (Luke Citation2012), with home literacies viewed as inferior (Cruickshank Citation2004), ‘to be compensated for by enhanced schooling’ (Street and Street Citation1991, 143). Knowledge from home (González, Moll, and Amanti Citation2009), in form of language, literacy practices, or cultural understanding, may go unrecognised in formal education contexts, despite clear evidence that reading literature which is representative of children’s lives has a positive impact on self-esteem, identity development, and reading motivation (Stewart Citation2017). Once school begins, families face curriculum-linked standardised tests and learning goals, all of which are singularly focused on the English language, leading to many parents prioritising English over the heritage language (Kwon Citation2017; Little Citation2017, Citation2020).

Methodology

Rivers of reading and critical incident technique

The Rivers of Reading (Cliff Hodges Citation2010) approach provides the cornerstone for data collection, as well as philosophical underpinnings. The methodology adapts Burnard’s (Citation2002) Rivers of Experience framework, asking children to consider their reading history as a flowing, changing river, identifying key reading resources (books, magazines, etc.) or moments within it. The methodology facilitates an understanding of children’s views from both a spatial and temporal perspective (Cliff Hodges Citation2010). This is especially important when one considers potential milestones within multilingual families which may impact language use, such as migration, school start, holidays, etc. (Cho and Krashen Citation2000).

The methodology further draws on Critical Incident Technique (Flanagan Citation1954). One key difference to Flanagan’s (Citation1954) approach is that, in Rivers of Reading, the locus of control is with the child, rather than the observer, in deciding what constitutes a ‘critical incident’. Nylén and Isomöttönen (Citation2017), to facilitate reflective learning, asked students to keep a learning diary and self-report critical incidents. The short length of entries presented a challenge to the authors, a limitation this study overcomes by combining children’s Rivers of Reading with multiple family interviews. Choice of books/resources, and linked critical incidents combined, invite narratives, which are often emotional in nature. In multilingual contexts, the incidents, narratives and resources chosen help to highlight points on the continua of biliteracy development (Hornberger Citation2004), with family interviews a vital part of data collection.

Family interviews

Tsikata and Darkwah (Citation2014) argue that family interviews support research in multilingual, intergenerational contexts, facilitating the emergence of narratives. Although this study only encompassed two generations (parents and children), the parents’ input helped children recall early literacy experiences. They were typically able to contextualise children’s narratives and were generally considered more ‘factually accurate’ respondents (regarding dates, family members, etc.), which placed the children’s experiences in an important ‘experienced context’, enabling the sharing of emotions and attitudes. Thus, the triangulation of parents’ and children’s recollections assisted the overall interpretation of data. Family interviews not only add depth to the data collection process, but also help the families themselves in affirming relationships (Eggenberger and Nelms Citation2007), something I return to in the conclusion.

The length of interviews varied, the first interview being typically the longest. Across the study, the shortest interview was 23 minutes, the longest 105 minutes, with a mean length of 46 minutes per interview. Each interview had a specific focus – the first one explored family background, with all participating family members creating a language portrait (Bush Citation2012). For reasons of space, the language portraits are not analysed separately in this paper, instead, they encouraged family communication about language, rather than in the family language (Little Citation2020). At the end of the first interview, the River of Reading methodology was introduced via a hand-out which explained the concept, asked families to contextualise resources chosen within other life events, and emphasised freedom of choice regarding the creative medium chosen. Above all, it highlighted the need for the activity to be child-led, with parents supporting in supplying historical details where appropriate. The second interview focused on children introducing their River of Reading, featuring only follow-up questions to ask for elaboration and check for understanding. The final interview focused primarily on catching up with families and children’s reading habits after a roughly 6-7-month gap. Me being a bilingual mother of a child in the research age range facilitated familiarity with children’s descriptions of books and authors, and better understanding on many family experiences.

Sample and recruitment

As in Cliff Hodges’ (Citation2010) work, the purpose of this study was to explore reading habits of committed readers, since children needed to be able to have choices when constructing their Rivers of Reading, to help understand attitude and ability related to the various languages. Due to the retrospective aspect of the study, however, current reading in the heritage language was not a requirement, since one purpose was to understand reading patterns over time.

Families were recruited via social media and multilingual mailing lists, as well as word of mouth. Funding restricted recruitment to six families, which stopped once this number was reached. All families fitting the criteria (multilingual household, child aged 8–13 years of age, self-classified reader) were included. The youngest child was 8 years 11 months at the first interview.

The six families between them had seven children eligible for the study. Four were male, three female. Languages spoken were Hebrew, Slovak, Polish, Spanish, Hungarian, and Dutch. Two families were single-parent households, three were two-parent households, and in one, parents were separated with shared custody. In one dual-parent family and both single-parent families, all parents in the household were native speakers of the heritage language, while the other four were mixed, one parent speaking the heritage language as a first language, the other English. In five families, parents were the first generation to migrate to an English-speaking country, in one family, the grandparents. In three families, the children themselves had experienced migration. Two of the children had formal lessons in the heritage language, either through complementary schooling, or through online tuition. Six children were in formal education, one was home-schooled. All family members were confident English speakers, which doubtlessly impacted on the results. With this study highlighting the value of the methodology, it is hoped that future studies will take the work to specific language communities, to widen our understanding further.

From the spread of participants, it is immediately clear that there is no ‘standard’ heritage language family (Little Citation2020). The combinations in family composition, language, and migration are manifold even before considering language practices. The study therefore does not claim representativeness. Instead, each family’s uniqueness is viewed as a strength, providing rich insights into multi-faceted experiences less likely in a more homogenous study.

Data analysis

The study includes two complementary forms of data. First, the Rivers of Reading themselves, in a variety of formats, each combining text and imagery. Second, transcripts from three family interviews, of which the second was dedicated to talking about the child’s River of Reading, eliciting stories behind choices, understanding spatial arrangement, and drawing out linked incidents which were not necessarily made explicit in the River itself. These two forms of data therefore required similarly complementary forms of analysis.

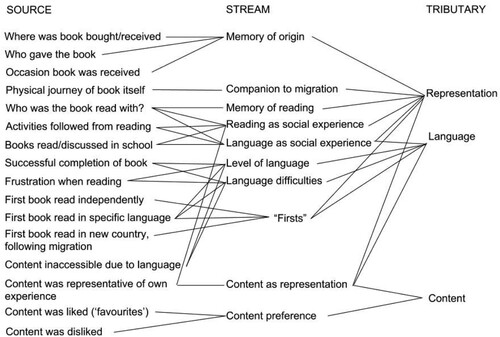

Both fully deductive and fully inductive research approaches have been problematised (Shepherd and Sutcliffe Citation2011) – one for its focus on problems without acknowledging unanticipated outcomes, the other for claiming an unrealistic ‘sense of wonder’ in research which seeks to address current issues. Following Shepherd and Sutcliffe’s recommendations, this study adopted an ‘inductive top-down approach’, with research literature influencing the design, whilst still allowing for data-driven theory development. Transcripts were coded inductively, nevertheless, certain themes had been defined by the literature: it seemed likely that likes and dislikes of books would be given as reasons, as would family associations and other emotional links (Cliff Hodges Citation2010). These did indeed appear in the data, and were enhanced with further emerging codes (language, different ‘firsts’, origins), leading to the ‘Source’ codes identified below. Grouped together, Sources formed epistemologically related ‘Streams’, which ultimately became the ‘Tributaries’ of the river, highlighting representation, language, and content as three over-arching core reasons why children include a book in their River of Reading. The full coding framework is presented below.

Ethics

Considering the focus on personal narratives in this study, anonymity required careful consideration. The sample description above applies holistically to all six families, rather than providing details for individuals. While some further conclusions are possible from the data, the practice of amalgamation protects participants’ identities (Graham et al. Citation2013). All children are referred to by pseudonyms. Families were made aware as part of the consent-seeking process that close friends might identify them, particularly if the family themselves had shared their involvement in the research, or they were recruited through snowball sampling (Moosa Citation2013).

Bagley, Reynolds, and Nelson (Citation2007) suggest that a wage-payment model commensurate with effort is appropriate for older children. Three interviews with multiple family members, plus time spent on creating Rivers of Reading, were deemed a considerable imposition on family time, therefore each family received a £100 voucher for participating.

Findings

This section first gives a background to children’s reading habits in general, as well as relevant family background, in order to contextualise later narratives. The following sections introduce children’s choices regarding layout and composition of their River of Reading, before then using the three Tributaries introduced above as a structure.

Initial reading habits and attitudes

Before children constructed their Rivers of Reading, the first interview focused on family language policy, language use, general attitude towards reading, and reading habits. Most children’s responses showed confidence discrepancies between their languages, impacting on their general enjoyment. Asked about her thoughts on reading in the heritage language, Sophie (age 9) replied:

I do like reading in Slovakian but not as much as in English because I don’t really practise that much in Slovakian, so sometimes it gets frustrating if I don’t know the word. Because I keep on reading […] the same word over and over again but I don’t know what it means. And then I’m like ‘mummy what does it mean’ and she tells me and I’m like ‘oh yes, that’s right’ and then it makes sense. (Sophie, 9, interview 1)

Mariana, aged 11, who moved to the UK from Spain 3.5 years prior, had the most formal education in the heritage language, and the home was ‘100% Spanish’ (mother). Nevertheless, she expressed a preference for English, for both linguistic and social reasons: ‘when I write in English it’s easier for me. But when I write in Spanish it’s like wrong … […] there’s quite a lot of things that it doesn’t make sense’ (Mariana, 11, interview 1).

She explained her preference by referencing the social culture around her:

I’m more used to the books in here, the authors. Because I like David Walliams, you know. And in Spain there’s not that, there’s books that I just have no idea what they are, so I’m not used to these books. (Mariana, 11, interview 1)

Benedict (age 11) commented, in reference to reading and writing the language: ‘What’s the point in learning about [Hungarian] and then I live in England?’, an attitude echoed by Liam (age 8). In both boys’ views, developing spoken language skills sufficed for communicating with family and friends. Low confidence in literacy skills played an additional role, but for Liam, even reading well had unwelcome consequences:

And once or twice, I didn’t tell [Dad] this, because I know what’s going to happen if I did tell him, once I read some of a book on my own and I understood it. I read one chapter and I understood it. […] I know what’s going to happen if I did, [Dad] would up my reading level and give me something really hard. (Liam, 8, interview 1)

For two children, reading in the heritage language was a structured activity that took place under supervision, mimicking a formal education environment. Once children had completed the Rivers of Reading exercise, positive comments about parental input increased (see below). While all children had read in the heritage language at some point, the balance between languages differed, with English dominating for all but one.

All families had enabled children to access books in the heritage language, despite asynchronous literacy development. Collin owned two versions of a book about the computer game Minecraft, in both English and Slovakian:

I read the Slovakian one first because it’s harder in my opinion. And then I read the other one to see if, like, I knew what it said. (Collin, 11, interview 1)

Conversely, both Isabella (Polish) and Mariana (Spanish) stated that they might choose to read a book in the heritage language if they had already read and liked it in English. Isabella explained that she would ‘tend to read the book in English but listen to it in Polish at the same time’ (Isabella, 12, interview 1), making reading a multimodal experience.

Rivers of reading

All children were told to represent their river in any way they chose, and nearly all decided on a chronological approach, as might be expected from the river analogy, which suggests linearity. Nevertheless, all chose a slightly different way to organise their River, as summarised below ().

Table 1. Rivers of Reading tools and structure.

All children approached their Rivers of Reading in individual ways, sometimes for practical reasons: spending part of their time with each parent separately, Sophie and Collin drew inspiration from their bookshelves in each house, using these as starting points. Some introduced milestones in the River of Reading structure itself, whereas Isabella and Benedict structured purely by age, giving milestones only verbally, thus highlighting the importance of pairing the artefact with narrative interviews.

Interestingly, the three children with first-hand migratory experiences adopted the most complex categorisations. Luuk, who has lived in the Netherlands, the UK, and Mexico, structured his River of Reading by location, and, within this, authors, typically separating by language.

Liam created 3D paper boats on a painted, chronological river approximately 1.5 m long, each carrying a book cover as a ‘passenger’. Boats were colour-coded as follows:

Green Boats – Favourite Books

Red Boats/Murky Water – Least Favourite Books

Orange Boats – Books Read in Hebrew

Yellow Boats – Non-Fiction

Books in Water – Adventure Books

In Liam’s structure, ‘Hebrew’ takes precedence over other categorisations, i.e. a non-fiction Hebrew book is orange, not yellow. It appears he could not, initially, see beyond the barrier Hebrew presented, as is further discussed above and below.

Mariana’s design (consisting of multiple, lengthwise taped sheets of A4) made most reference to traditional ‘critical incidents’ (Flanagan Citation1954). She marked her move to England, and her River of Reading subsequently shows a wavy line down the middle of the paper, English books on one side, Spanish books on the other. This separation continues for a page and a half, followed by a page of English books only. On the final page, English and Spanish books intermingled. When asked, Mariana exclaimed that she had not been aware of the final joining of the languages, potentially a sign that languages are becoming more interchangeable as her literacy confidence increased. The unconscious ultimate mingling of languages also featured in Luuk’s trilingual River of Reading:

So now, so this is the first slide that mixes all three languages.

It does actually, I haven’t seen that.

Luuk, 9, interview 2

Reasons for inclusion of books and other reading materials

No detailed coding framework for the analysis of Rivers of Reading has been published so far. As outlined above, multilingual children had complex, overlapping reasons to include a book in their River of Reading, with the children’s language and migratory experiences impacting on all core sections. This framework is offered below, for scrutiny, application, and expansion in future research projects, as a core methodological contribution to researching children’s multilingual reading experiences ().

Below, each Tributary is individually explored, highlighting some of the over-arching complexities.

Tributary one: representation

Many resources were included because they represented specific memories. Luuk, age 9, listed various Donald Duck books in his River of Reading, but singled out two, because they had travelled with him on several migration journeys. His mother put the journey in order:

We bought them in May when we went to Azerbaijan, May 2016, so [to Luuk] you were almost 7. […] We bought them in the Netherlands, then they went to Azerbaijan, then back to the Netherlands, then to Mexico, then to [the UK]. (Luuk’s mother, interview 2)

For Liam (age 9), it was not just the books he chose, but also the space in-between, that was representative of migration in his River of Reading:

There’s a big gap here because we moved and it was hard to read.

Why was it hard?

Because we were still getting organised and I had to unpack suitcases instead of sitting down with a book. Liam, 9, Interview 2

All children had examples of social representation, shared reading or family engagement, right up until the present day, particularly in the heritage language. Benedict, for example, talked about reading newspaper articles about horse racing with a grandparent, while Sophie and her mother talked about a girls’ crafts book:

They’re based like for Slovak kids, and I remember there is how to make a daisy chain. And do you remember when I made you one from dandelions and then you said ‘mummy there is how to make it in my book’ and you showed me. (Sophie’s mother, interview 2)

Out of all children, Mariana (age 11 at start of study) provided most contextualisation between her reading and her daily life. She was the only child who not only provided spoken commentary, but also annotated each individual book in her River of Reading. Shortly after arriving in the UK, her stepfather gave her the Brownie Annual [Brownies are part of the UK Scouts organisation]. In her annotation, she explains that this was:

So I could know more about british way of life. He also bought it because there were some exercise to practise my english. 2 years later, I went to Brownies! Mariana, 12, River of Reading, annotation. (spellings original)

While also have language-related connotations, the entry is clearly representative of Mariana’s own journey, illustrating narratives around language, cultural connections, and identity (Stewart Citation2017). By contrast, books in English had representative links to school, through origin (bought at school book fairs), recommendations (in-class readings) or subject links.

Section summary

Children chose books and sources as being representative for, or accompanying them on, significant milestones. While all children had books which signified or accompanied change, the children with personal migration histories expressed the strongest connections to such books, possibly because they took on a special meaning when choices had to be made about what to leave behind (and what to take) when starting a new life. There were some hints towards identity in books representing a certain way of life, or being for children who spoke the heritage language (‘Slovak kids’), reminiscent of previous research (Little Citation2019). Further research is needed here to fully grasp these connections.

Tributary two: language

As with migration experiences above, language skills (or the lack thereof) were also given as reasons for the absence of books in the River of Reading. Benedict (age 11) was not confident reading in Hungarian, so his books after age seven were exclusively in English, although the interview revealed him reading newspaper articles about horse racing (highlighted above). Reading in the heritage language was again embedded in a social, family-related experience (Moll, Saez, and Dworin Citation2001).

Asynchronous biliteracy became apparent in multiple ‘Source’ codes, including ‘frustration when reading’, and ‘content inaccessible due to language’, as barriers to content enjoyment. It was raised by almost all families as an issue at varying ages, and in varying contexts. Collin (aged 11) explained that, up until age seven, he read books of similar difficulty in English and Slovakian, but as he got older, a biliteracy gap developed.

Through discussing their Rivers of Reading, several children situated parental input as positive, helpful, or part of a shared experience.

Well what tends to happen with Polish reading is, I hit a block and then I panic and I stop reading it. […] Well then I read it with my mum, and it turns out it wasn’t that bad. (Isabella, 12, interview 2)

Mariana and her mother made a habit of co-reading the same book in English when they first moved to England:

This [book] is like really, really, really funny. My mum and I laughed because my mum and I, we used to learn English by reading together and we understood it really well, so it was a really good book. (Mariana, 11, interview 2)

Data show that while access to resources is important (Krashen Citation1993), developing strategies that deal with asynchronous biliteracy is vital, both how resources are used (visually (Collin) or multimodally (Isabella)), and/or the involvement of parents as co-readers and enablers (Mariana, Isabella, Sophie).

Interestingly, while content deemed ‘too young’ for children themselves caused frustration (see Content Tributary below), adding younger family members into the mix overcame these issues, framing the children themselves as heritage literacy enablers (Gregory Citation1998). Liam (age 9) included Hebrew picture books towards the end of his River of Reading, which he read to his younger sister:

Over here, I read this [Hebrew picture book] with [my sister].

You read that one with her. So that’s interesting. So kind of, as your River of Reading ends there it …

It also begins. Hers begins. (Liam, 9, interview 2)

Considering his previously recounted difficulties and attitudes, hearing Liam describe a Hebrew book as ‘really good’ is an important milestone. Younger family members also formed a bridge to biliteracy development for Benedict (age 11), as explored in the final interview:

So do you still read anything in Hungarian?

Sometimes. I struggle though. Like once, […] I think it was at my little cousin, she wanted me to read [a book] out. […] So then I like … .there were some words I really didn’t understand. So, I started it out and then I saw the accents on it which really got me, and then I just started to make up my own story. (Benedict, 11, interview 3)

Section summary

Language-related codes highlighted a duality as they linked to emotions, specifically success or frustration, connected to reading in the heritage language. Social connections had a vital role to play here, with parents, grandparents, but also younger family members enabling biliteracy development (Gregory Citation1998). While children’s attitude towards parental involvement was mixed, younger family members (where relevant) held a non-threatening status which allowed children to take on the role as biliteracy broker.

Tributary three: content

For the children who were confident in their reading skills, content was more likely to appear as a singular reason, without additional qualifiers. For those who struggled with reading, content was of interest as part of narratives around asynchronous development. Liam’s parents sought advice on suitable books in Hebrew during a visit to a bookshop in Israel:

We told them what he liked and we told them like his reading level, and they recommended a couple of books. […] I think it’s a little bit younger in terms of the reading. (Liam’s mother, interview 2)

Language and literacy skills are a barrier to accessing suitable content, highlighting again the confluences of Tributaries. Nevertheless, the most recent book in Liam’s River of Reading is in Hebrew, and the first one where he acknowledges he likes the plot, and might have chosen to read it, even without parental encouragement. Harking back to earlier comments about asynchronous literacy development, this shows that accessing literature which allows children to identify with content (Stewart Citation2017) is important, but may be more difficult in the heritage language (Worthy, Nuñez, and Espinoza Citation2016).

There was a marked difference in books and resources linked primarily to content in the heritage language, versus in English. However, interest in content could also facilitate discussion that highlighted biliteracy. Benedict (age 11), for example, had included a football programme in English (‘Because I like football and I support Man City’, interview 2). When asked about reading in Hungarian, he initially stated that he couldn’t, prompting his mother to remind him of an article he had read: ‘Yes you can, you read the article out loud. Because it’s football, it was football and it was more interesting’ (Benedict’s mother, interview 2). This was just one of many examples where parents served as children’s ‘memory’, providing context and discussion around the Rivers of Reading, and facilitating children’s narratives.

Luuk (age 9), the most confidently biliterate participant, was most likely to include books in the heritage language based on content alone, followed by Isabella (age 13) and Mariana (age 11). This sample includes two children with formal heritage language schooling, and two in fully-immersed heritage language homes, showing clearly the ‘Matthew Effect’ (Stanovich Citation1986) in action, with language and literacy confidence leading to enjoyment. Parents again played a strong role, with all three children stating that they discussed their reading with their parents, and that parents might read the same books, in order to be able to discuss them with their children (Eggenberger and Nelms Citation2007).

Section summary

Content became more relevant with confidence in literacy – an important aspect when we consider that, in reading for pleasure, content is arguably the most common reason for picking up a book. Access to appropriate resources that bridge biliteracy gaps therefore remains a priority – as well as ways to scaffold and enable children to reach that critical mass that will allow them to make the jump to content-based choices.

Conclusion

The data show that parents adopt many strategies to engage their children in reading in the heritage language, and that parental engagement in children’s reading journey occurred across all age ranges, showing the need for ongoing parental and social support for their children to develop biliteracy (Li Citation2006), especially if the education system cannot be utilised for this purpose (Worthy, Nuñez, and Espinoza Citation2016).

Reasons for including books are more varied than for monolingual readers, with children providing a complex network of emotional and linguistic reasons, woven into narratives of heritage language learning journeys, migratory experiences, and family cohesion. These social narratives are worth exploring further, particularly in comparing home and school social networks for literacy development. The term ‘reading for pleasure’ in this context may need to be re-defined, since most children mentioned at least some frustration, at some point, in their multilingual reading journey. Nevertheless, the complex reasons for including reading materials in their Rivers of Reading show that the children can negotiate multifaceted emotional responses to reading material, which can be utilised in supporting their biliteracy development, and in support of Hornberger’s (Citation2004) continua of biliteracy model.

All children were able to provide critical incidents that referred to their heritage language literacy development, and/or compare this to their English literacy development. Emotional attachments such as success or frustration were far more common in heritage languages, especially in those children whose literacy development was asynchronous. Children who self-identified as more or less balanced in their literacy development, however, were much more likely to foreground content. The absence of books at certain times was highlighted by several children, making this ‘negative space’ an important opportunity for future research about biliteracy disruption due to migration or other experiences. The River of Reading also served to highlight achievements, with five out of seven children expressing surprise at the amount of books they had read in the heritage language. This makes the methodology a useful tool for validating multilingualism.

The enthusiasm with which both parents and children embraced the task, and the reflective discussions the process elicited, make the exercise of particular value in facilitating school-home communication: the Rivers of Reading methodology aids in making visible not only multilingual skills, but also has the potential to highlight issues around language shift, availability of resources, reading preferences, and is a straightforward way to validate home languages in the formal education context. It could, for example, form part of a school audit into languages spoken, and resources available, such as in the school library, and lead to further work, such as multilingual book reports or displays.

Several parents underwent a developmental journey themselves, becoming more active in asking and listening to their children’s views as the interviews progressed:

Oh yeah, I’ve read a little bit of Hebrew and I’ve improved, started recognising words. Hebrew’s not like English, different letters make different sounds in different ways and that makes it distressing. […]

When you say ‘distressing’ what do you mean by that?

Just … .erm … .it’s not something I enjoy doing.

Do you enjoy being read to in Hebrew?

Yeah. I don’t really find a difference between being read in English and being read in Hebrew […]

I know that we bought some books in Hebrew that you’ve already read in English, how do you feel about reading those?

Feel better. Sure, confident in reading those books I already read in English. (Liam, 9, and Mum, Interview 3)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sabine Little

Sabine Little is a Lecturer in Languages Education at the University of Sheffield. Her research focuses on multilingualism at home and in schools, with a specific interest in supporting identity development in multilingual children through the valorisation and validation of multilingualism in public/educational contexts.

References

- Bagley, S. J., W. W. Reynolds, and R. M. Nelson. 2007. “Is a “Wage-Payment” Model for Research Participation Appropriate for Children?” Pediatrics 119 (1): 46–51. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1813.

- Burnard, P. 2002. “Using Image-Based Techniques in Researching Pupil Perspectives.” The ESRC Network Project Newsletter 5: 2–3.

- Bush, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056.

- Cho, G., and S. D. Krashen. 2000. “The Role of Voluntary Factors in Heritage Language Development: How Speakers Can Develop the Heritage Language on Their Own.” ITL – International Journal of Applied Linguistics 127–128: 127–140. doi:10.1075/itl.127-128.06cho.

- Cliff Hodges, G. 2010. “Rivers of Reading: Using Critical Incident Collages to Learn About Adolescent Readers and Their Readership.” English in Education 44 (3): 181–200. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2010.01072.x.

- Creese, A., C.-J. Wu, and A. Blackledge. 2009. “Folk Stories and Social Identification in Multilingual Classrooms.” Linguistics and Education 20 (4): 350–365. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2009.10.002.

- Cruickshank, K. 2004. “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts: Change in Teenagers’ Reading and Writing.” Language and Education 18 (6): 459–473. doi:10.1080/09500780408666895.

- Eggenberger, S. K., and T. P. Nelms. 2007. “Family Interviews as a Method for Family Research.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 58 (3): 282–292. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04238.x.

- Fishman, J. A. 1964. “Language Maintenance and Language Shift as a Field of Inquiry. A Definition of the Field and Suggestions for its Further Development.” Linguistics 2 (9): 32–70. doi:10.1515/ling.1964.2.9.32.

- Flanagan, J. C. 1954. “The Critical Incident Technique.” Psychological Bulletin 51 (4): 327–358. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1955-01751-001.

- González, N., N. C. Moll, and C. Amanti, eds. 2009. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities and Classrooms. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Graham, A., M. Powell, N. Taylor, D. Anderson, and R. Fitzgerald. 2013. Ethical Research Involving Children. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/eric-compendium-approved-digital-web.pdf.

- Gregory, E. 1998. “Siblings as Mediators of Literacy in Linguistic Minority Communities.” Language and Education 12 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1080/09500789808666738.

- Hornberger, N. H. 2004. “The Continua of Biliteracy and the Bilingual Educator: Educational Linguistics in Practice.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 7 (2-3): 155–171. doi:10.1080/13670050408667806.

- Kenner, C. 2004. Becoming Biliterate: Young Children Learning Different Writing Systems. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

- King, K., and L. Fogle. 2006. “Bilingual Parenting as Good Parenting: Parents’ Perspectives on Family Language Policy for Additive Bilingualism.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 9: 695712. abs/102167/beb362.0.

- Krashen, S. 1993. The Power of Reading. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

- Kwon, J. 2017. “Immigrant Mothers’ Beliefs and Transnational Strategies for Their Children’s Heritage Language Maintenance.” Language and Education 31 (6): 495–508. doi:10.1080/09500782.2017.1349137.

- Li, G. 2006. “Biliteracy and Trilingual Practices in the Home Context: Case Studies of Chinese-Canadian Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 6 (3): 355–381. doi:10.1177/1468798406069797.

- Little, S. 2017. “A Generational Arc: Early Literacy Practices Among Pakistani and Indian Heritage Language Families.” International Journal of Early Years Education 25 (4): 424–438. doi:10.1080/09669760.2017.1341302.

- Little, S. 2019. “Is There an App for That?” Exploring Games and Apps Among Heritage Language Families.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (3): 218–229. doi:10.1080/01434632.2018.1502776.

- Little, S. 2020. “Whose Heritage? What Inheritance? Conceptualising Family Language Identities.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (2): 198–212. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1348463.

- Luke, A. 2012. “After the Testing: Talking and Reading and Writing the World.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 56 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1002/JAAL.00095.

- Menken, K. 2013. “Emergent Bilingual Students in Secondary School: Along the Academic Language and Literacy Continuum.” Language Teaching 46 (4): 438–476. doi:10.1017/S0261444813000281.

- Moll, L. C., R. Saez, and J. Dworin. 2001. “Exploring Biliteracy: Two Student Case Examples of Writing as a Social Practice.” The Elementary School Journal 101 (4): 435–449. doi:10.1086/499680.

- Moosa, D. 2013. “Challenges to Anonymity and Representation in Educational Qualitative Research in a Small Community: A Reflection on my Research Journey.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1080/03057925.2013.797733.

- Nylén, A., and V. Isomöttönen. 2017. “Exploring the Critical Incident Technique to Encourage Reflection During Project-Based Learning.” ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 16: 88–97. doi:10.1145/3141880.3141899.

- Pease-Alvarez, L. 2002. “Moving Beyond Linear Trajectories of Language Shift and Bilingual Language Socialization.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 24 (2): 114–137. doi:10.1177/0739986302024002002.

- Shepherd, D. A., and K. M. Sutcliffe. 2011. “Inductive Top-Down Theorizing: A Source of New Theories of Organization.” The Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 361–380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41318005.

- Song, K. 2016. “Nurturing Young Children’s Biliteracy Development: A Korean Family’s Hybrid Literacy Practices at Home.” Language Arts 93 (5): 341–353.

- Stanovich, K. E. 1986. “Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy.” Reading Research Quarterly 21: 360–406. https://www.psychologytoday.com/files/u81/Stanovich__1986_.pdf.

- Statista. 2018. Percentage of Primary and Secondary Pupils with English as an Additional Language in England from 1997 to 2018. https://www.statista.com/statistics/330782/england-english-additional-language-primary-pupils/.

- Stewart, M. A. 2017. “I Love This Book Because That’s Like Me! A Multilingual Refugee/Adolescent Girl Responds from Her Homeplace.” International Multilingual Research Journal 11 (4): 239–254. doi:10.1080/19313152.2016.1246900.

- Street, B., and J. Street. 1991. “The Schooling of Literacy.” In Writing in the Community, edited by D. Barton and R. Ivani, 72–85. London: Sage.

- Tse, L. 2001. “Resisting and Reversing Language Shift: Heritage-Language Resilience among U. S. Native Biliterates.” Harvard Educational Review 71 (4): 676–708. doi:10.17763/haer.71.4.ku752mj536413336.

- Tsikata, D., and A. K. Darkwah. 2014. “Researching Empowerment: On Methodological Innovations, Pitfalls and Challenges.” Women’s Studies International Forum 45: 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2014.03.012.

- Veltman, C. 1983. Language Shift in the United States. Berlin: Mouton Publishers.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465.

- Worthy, J., I. Nuñez, and K. Espinoza. 2016. “Wow, I Get to Choose Now!” Bilingualism and Biliteracy Development from Childhood to Young Adulthood.” Bilingual Research Journal 39 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1080/1525882.2016.1139518.